Case Study 4.2: University of California’s Accessibility Guides

Douglas Harriman, in describing the UC’s recently created accessibility guides at the 2021 CSUN Conference, noted the importance of meeting learners where they are at. He suggested that accessibility training materials move away from prescriptive, one-size-fits-all solutions toward training that empowers learners to make their own judgments based on accessibility principles.

Harriman advised taking several questions into account when designing accessibility training materials. These questions include:

- What standards are you trying to achieve? Point these out in training materials.

- Why are these requirements important? Empower learners to make independent decision based on what they have learned.

- How can accessibility standards be achieved? Show how this works rather than merely telling. Link to definitions/demos.

- How can these techniques be incorporated into the learner’s everyday workflow? Confront the notion that accessibility work is too time-consuming to accomplish.

- How can accessibility standards be verified without resorting to an automated checker? Encourage learners to make judgments without relying on tools that may overstate, understate, or miss particular accessibility concerns.

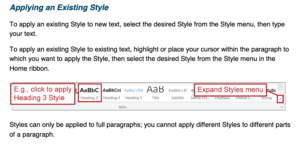

Harriman noted how the University of California attempted to put these principles to work in their Word-to-PDF and PDF Accessibility Guide. One small example comes from the guide’s discussion of headings. The guide explains the importance of using headings to structure a Word document. Then it demonstrates how to change heading styles so as to quickly and flexibly apply desired fonts and sizing (see screenshot below). In this way, the guide demonstrates an accessibility principle while suggesting ways of putting it into practice as part of the learner’s everyday workflows.

As a final note, when you are designing accessibility training materials, you may want to think critically about your use of checklists. Kelsie Acton and Dieuwertje Dyi Huijg have noted that accessibility checklists can be reductive, unnuanced, and putative toward faculty members with their own accessibility needs. WebAIM also suggests in their “Hierarchy for Motivating Accessibility Change” that checklists may ineffectively appeal to guilt and fear rather than producing change through inspiration and enlightenment. Some have remarked that while general accessibility checklists are unhelpful, systems-specific and contextually based ones can be useful, so you will have to weigh the merits/drawbacks for yourself.