Learning Objectives

After reading this section, students should be able to …

1. outline the ways in which markets are segmented.

2. explain why marketers use some segmentation bases versus others.

Segmentation is an important strategic tool in international marketing because the main difference between calling a firm international and global is based on the scope and bases of segmentation. An international firm has different marketing strategies for different segments of countries, while a global firm views the whole world as a market, and then segments this whole world based on viable segmentation bases. Generally, there are three approaches to segmentation in international marketing: macro-segmentation, micro-segmentation and the hybrid approach.

Macro-segmentation:

Macro-segmentation or country-based segmentation identifies clusters of countries that demand similar products. Macro-segmentation uses geographic, demographic and socioeconomic variables such as location, GNP per capita, population size or family size to group countries intro market segments, and then selects one or more segments to create marketing strategies for each of the selected segments. This strategy enables a company to centralize its operations and save on production, sales, logistics and support functions. However, macro-segmentation doesn’t take into consideration consumer differences within each country and among the country markets that are clustered together, and fails to acknowledge the existence of segments that go beyond the borders of a particular geographic region. Therefore, the company may be leaving money on the table, because the firm may be losing opportunities to solve the need of consumer segments across these country segments. Macro-segmentation leads to misleading national stereotyping, which results in neglect of within-country heterogeneity. Ignoring similarity in needs across country boundaries results in countries losing economies of scale benefits that can be achieved by serving the needs of a wider population across country (macro-segment) boundaries.

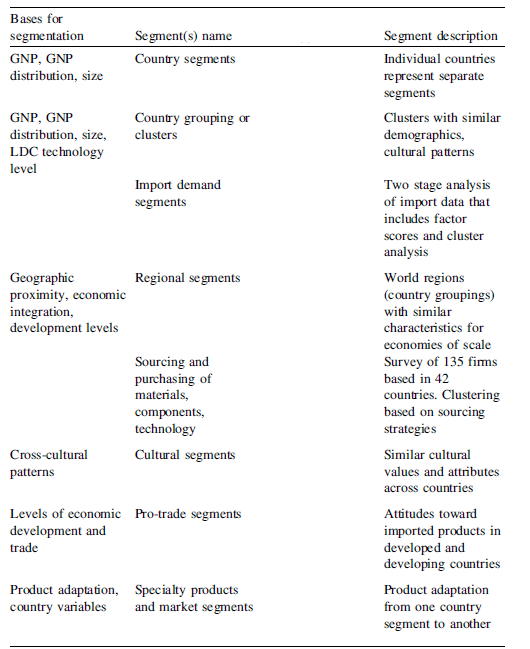

Table 6.5: Macro-segmentation bases

Source: Adapted from Hassan, Craft and Kortam (2003)

Micro-segmentation:

Micro-segmentation or consumer-based segmentation involves grouping consumers based on common characteristics using psychographic and/or behavioristic segmentation variables such as cultural preferences, values and attitudes, lifestyle choices. Table 6.6 “Micro-segmentation bases” and Table 6.7 “Common Ways of Segmenting Buyers” show some of the different types of buyer characteristics used for micro-segmentation. Notice that the characteristics fall into one of four segmentation categories: behavioral, demographic, geographic, or psychographic.

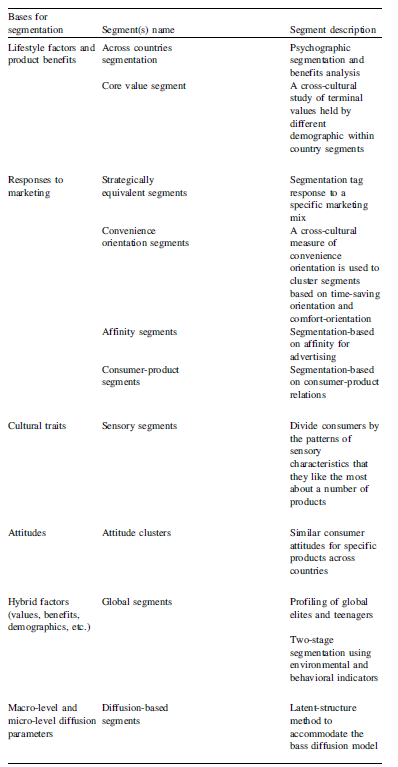

Table 6.6 “Micro-segmentation bases”

Source: Adapted from Hassan, Craft and Kortam (2003)

We’ll discuss each of these categories in a moment. For now, you can get a rough idea of what the categories consist of by looking at them in terms of how marketing professionals might answer the following questions:

•Behavioral segmentation:What benefits do customers want, and how do they use our product?

•Demographic segmentation: How do the ages, races, and ethnic backgrounds of our customers affect what they buy?

•Geographic segmentation: Where are our customers located, and how can we reach them? What products do they buy based on their locations?

• Psychographic segmentation: What do our customers think about and value? How do they live their lives?

Table 6.7 Common Ways of Segmenting Buyers

| By Behavior | By Demographics | By Geography | By Psychographics |

| • Benefits sought from the product • How often the product is used (usage rate) • Usage situation (daily use, holiday use, etc.) • Buyer’s status and loyalty to product (nonuser, potential user, first-time users, regular user) |

• Age/ generation • Income • Gender • Family life cycle • Ethnicity • Family size • Occupation • Education • Nationality • Religion • Social class |

• Region (continent, country, state, neighborhood) • Size of city or town • Population density • Climate |

• Activities • Interests • Opinions • Values • Attitudes • Lifestyles |

Segmenting by Behavior

Behavioral segmentation divides people and organization into groups according to how they behave with or act toward products. Benefits segmentation—segmenting buyers by the benefits they want from products—is very common. Take toothpaste, for example. Which benefit is most important to you when you buy a toothpaste: The toothpaste’s price, ability to whiten your teeth, fight tooth decay, freshen your breath, or something else? Perhaps it’s a combination of two or more benefits. If marketing professionals know what those benefits are, they can then tailor different toothpaste offerings to you (and other people like you).

Another way in which businesses segment buyers is by their usage rates—that is, how often, if ever, they use certain products. Companies are interested in frequent users because they want to reach other people like them. They are also keenly interested in nonusers and how they can be persuaded to use products. The way in which people use products can also be a basis for segmentation.

Segmenting by Demographics

Segmenting buyers by personal characteristics such as age, income, ethnicity and nationality, education, occupation, religion, social class, and family size is called demographic segmentation. Demographics are commonly utilized to segment markets because demographic information is publicly available in databases around the world.

Age

At this point in your life, you are probably more likely to buy a car than a funeral plot. Marketing professionals know this. That’s why they try to segment consumers by their ages. You’re probably familiar with some of the age groups most commonly segmented (see Table 6.8 “U.S. Generations and Characteristics”) in the United States. Into which category do you fall?

Table 6.8 U.S. Generations and Characteristics

Generation |

Also Known As |

Birth Years |

Characteristics |

| Seniors | “The Silent Generation,” “Matures,” “Veterans,” and “Traditionalists” |

1945 and prior |

• Experienced very limited credit growing up • Tend to live within their means • Spend more on health care than any other age group • Internet usage rates increasing faster than any other group |

| Baby Boomers |

1946–1964 | • Second-largest generation in the United States • Grew up in prosperous times before the widespread use of credit • Account for 50 percent of U.S. consumer spending • Willing to use new technologies as they see fit |

|

| Generation X |

1965–1979 | • Comfortable but cautious about borrowing • Buying habits characterized by their life stages • Embrace technology and multitasking |

|

| Generation Y |

“Millennials,” “Echo Boomers,” includes “Tweens” (preteens) |

1980–2000 | • Largest U.S. generation • Grew up with credit cards • Adept at multitasking; technology use is innate • Ignore irrelevant media |

| Note: Not all demographers agree on the cutoff dates between the generations. |

Today’s college-age students (Generation Y) compose the largest generation. The baby boomer generation is the second largest, and over the course of the last thirty years or so, has been a very attractive market for sellers. Retro brands—old brands or products that companies “bring back” for a period of time—were aimed at baby boomers during the recent economic downturn. Pepsi Throwback and Mountain Dew Throwback, which are made with cane sugar—like they were “back in the good old days”—instead of corn syrup, are examples (Schlacter, 2009). Marketing professionals believe they appealed to baby boomers because they reminded them of better times—times when they didn’t have to worry about being laid off, about losing their homes, or about their retirement funds and pensions drying up.

So which group or groups should your firm target? Although it’s hard to be all things to all people, many companies try to broaden their customer bases by appealing to multiple generations so they don’t lose market share when demographics change. Several companies have introduced lower-cost brands targeting Generation Xers, who have less spending power than boomers. For example, kitchenware and home-furnishings company Williams- Sonoma opened the Elm Street chain, a less-pricey version of the Pottery Barn franchise. The Starwood hotel chain’s W hotels, which feature contemporary designs and hip bars, are aimed at Generation Xers (Miller, 2009).

The video game market is very proud of the fact that along with Generation X and Generation Y, many older Americans still play video games. (You probably know some baby boomers who own a Nintendo Wii.) Products and services in the spa market used to be aimed squarely at adults, but not anymore. Parents are now paying for their tweens to get facials, pedicures, and other pampering in numbers no one in years past could have imagined.

As early as the 1970s, U.S. automakers found themselves in trouble because of changing demographic trends. Many of the companies’ buyers were older Americans inclined to “buy American.” These people hadn’t forgotten that Japan bombed Pearl Harbor during World War II and weren’t about to buy Japanese vehicles, but younger Americans were. Plus, Japanese cars had developed a better reputation. Despite the challenges U.S. automakers face today, they have taken great pains to cater to the “younger” generation—today’s baby boomers who don’t think of themselves as being old. If you are a car buff, you perhaps have noticed that the once-stodgy Cadillac now has a sportier look and stiffer suspension. Likewise, the Chrysler 300 looks more like a muscle car than the old Chrysler Fifth Avenue your great-grandpa might have driven.

Automakers have begun reaching out to Generations X and Y, too. General Motors (GM) has sought to revamp the century-old company by hiring a new younger group of managers—managers who understand how Generation X and Y consumers are wired and what they want. “If you’re going to appeal to my daughter, you’re going to have to be in the digital world,” explained one GM vice president (Cox, 2009).

Income

Tweens might appear to be a very attractive market when you consider they will be buying products for years to come. But would you change your mind if you knew that baby boomers account for 50 percent of all consumer spending in the United States? Americans over sixty-five now control nearly three-quarters of the net worth of U.S. households; this group spends $200 billion a year on major “discretionary” (optional) purchases such as luxury cars, alcohol, vacations, and financial products (Reisenwitz, 2007).

Income is used as a segmentation variable because it indicates a group’s buying power and may partially reflect their education levels, occupation, and social classes. Higher education levels usually result in higher paying jobs and greater social status. The makers of upscale products such as Rolexes and Lamborghinis aim their products at high-income groups. However, a growing number of firms today are aiming their products at lower-income consumers. The fastest-growing product in the financial services sector is prepaid debit cards, most of which are being bought and used by people who don’t have bank accounts. Firms are finding that this group is a large, untapped pool of customers who tend to be more brand loyal than most. If you capture enough of them, you can earn a profit (von Hoffman, 2006). Based on the targeted market, businesses can determine the location and type of stores where they want to sell their products.

Gender

Gender is another way to segment consumers. Men and women have different needs and also shop differently. Consequently, the two groups are often, but not always, segmented and targeted differently. Marketing professionals don’t stop there, though. For example, because women make many of the purchases for their households, market researchers sometimes try to further divide them into subsegments. (Men are also often subsegmented.) For women, those segments might include stay-at-home housewives, plan-to-work housewives, just-a-job working women, and career-oriented working women. Research has found that women who are solely homemakers tend to spend more money, perhaps because they have more time.

Family Life Cycle

Family life cycle refers to the stages families go through over time and how it affects people’s buying behavior. For example, if you have no children, your demand for pediatric services (medical care for children) is likely to be slim to none, but if you have children, your demand might be very high because children frequently get sick. You may be part of the target market not only for pediatric services but also for a host of other products, such as diapers, daycare, children’s clothing, entertainment services, and educational products. A secondary segment of interested consumers might be grandparents who are likely to spend less on day-to-day childcare items but more on special-occasion gifts for children. Many markets are segmented based on the special events in people’s lives. Think about brides (and want-to-be brides) and all the products targeted at them, including Web sites and television shows such as Say Yes to the Dress, My Fair Wedding, Platinum Weddings, and Bridezillas.

Resorts also segment vacationers depending on where they are in their family life cycles. When you think of family vacations, you probably think of Disney resorts. Some vacation properties, such as Sandals, exclude children from some of their resorts. Perhaps they do so because some studies show that the market segment with greatest financial potential is married couples without children (Hill, et. al., 1990).

Keep in mind that although you might be able to isolate a segment in the marketplace, including one based on family life cycle, you can’t make assumptions about what the people in it will want. Just like people’s demographics change, so do their tastes. For example, over the past few decades U.S. families have been getting smaller. Households with a single occupant are more commonplace than ever, but until recently, that hasn’t stopped people from demanding bigger cars (and more of them) as well as larger houses, or what some people jokingly refer to as “McMansions.”

The trends toward larger cars and larger houses appear to be reversing. High energy costs, the credit crunch, and concern for the environment are leading people to demand smaller houses. To attract people such as these, D. R. Horton, the nation’s leading homebuilder, and other construction firms are now building smaller homes.

Ethnicity

People’s ethnic backgrounds have a big impact on what they buy. If you’ve visited a grocery store that caters to a different ethnic group than your own, you were probably surprised to see the types of products sold there. It’s no secret that the United States is becoming—and will continue to become—more diverse. Hispanic Americans are the largest and the fastest-growing minority in the United States. Companies are going to great lengths to court this once overlooked group. In California, the health care provider Kaiser Permanente runs television ads letting members of this segment know that they can request Spanish-speaking physicians and that Spanish-speaking nurses, telephone operators, and translators are available at all of its clinics (Berkowitz, 2006).

As you can guess, even within various ethnic groups there are many differences in terms of the goods and services buyers choose. Consequently, painting each group with a broad brush would leave you with an incomplete picture of your buyers. For example, although the common ancestral language among the Hispanic segment is Spanish, Hispanics trace their lineages to different countries. Nearly 70 percent of Hispanics in the United States trace their lineage to Mexico; others trace theirs to Central America, South America, and the Caribbean.

Segmenting by Geography

Suppose your great new product or service idea involves opening a local store. Before you open the store, you will probably want to do some research to determine which geographical areas have the best potential. For instance, if your business is a high-end restaurant, should it be located near the local college or country club? If you sell ski equipment, you probably will want to locate your shop somewhere in the vicinity of a mountain range where there is skiing. You might see a snowboard shop in the same area but probably not a surfboard shop. By contrast, a surfboard shop is likely to be located along the coast, but you probably would not find a snowboard shop on the beach.

Geographic segmentation divides the market into areas based on location and explains why the checkout clerks at stores sometimes ask for your zip code. It’s also why businesses print codes on coupons that correspond to zip codes. When the coupons are redeemed, the store can find out where its customers are located—or not located. Geocoding is a process that takes data such as this and plots it on a map. Geocoding can help businesses see where prospective customers might be clustered and target them with various ad campaigns, including direct mail. One of the most popular geocoding software programs is PRIZM NE, which is produced by a company called Claritas. PRIZM NE uses zip codes and demographic information to classify the American population into segments. The idea behind PRIZM is that “you are where you live.” Combining both demographic and geographic information is referred to as geodemographics or neighborhood geography. The idea is that housing areas in different zip codes typically attract certain types of buyers with certain income levels.

To see how geodemographics works, visit the following page on Claritas’ Web site: http://www.claritas.com/MyBestSegments/Default.jsp?ID=20.

Type in your zip code, and you will see customer profiles of the types of buyers who live in your area. Table 6.9 “An Example of Geodemographic Segmentation for 76137 (Fort Worth, TX)” shows the profiles of buyers who can be found the zip code 76137—the “Brite Lites, Li’l City” bunch, and “Home Sweet Home” set. Click on the profiles on the Claritas site to see which one most resembles you.

Table 6.9 An Example of Geodemographic Segmentation for 76137 (Fort Worth, TX)

| Number | Profile Name |

| 12 | Brite Lites, Li’l City |

| 19 | Home Sweet Home |

| 24 | Up-and-Comers |

| 13 | Upward Bound |

| 34 | White Picket Fences |

The tourism bureau for the state of Michigan was able to identify and target different customer profiles using PRIZM. Michigan’s biggest travel segment are Chicagoans in certain zip codes consisting of upper-middle-class households with children—or the “kids in cul-de-sacs” group, as Claritas puts it. The bureau was also able to identify segments significantly different from the Chicago segment, including blue-collar adults in the Cleveland area who vacation without their children. The organization then created significantly different marketing campaigns to appeal to each group.

In addition to figuring out where to locate stores and advertise to customers in that area, geographic segmentation helps firms tailor their products. Chances are you won’t be able to find the same heavy winter coat you see at a Walmart in Montana at a Walmart in Florida because of the climate differences between the two places. Market researchers also look at migration patterns to evaluate opportunities. TexMex restaurants are more commonly found in the southwestern United States. However, northern states are now seeing more of them as more people of Hispanic descent move northward.

Segmenting by Psychographics

If your offering fulfills the needs of a specific demographic group, then the demographic can be an important basis for identifying groups of consumers interested in your product. What if your product crosses several market segments? For example, the group of potential consumers for cereal could be “almost” everyone although groups of people may have different needs with regard to their cereal. Some consumers might be interested in the fiber, some consumers (especially children) may be interested in the prize that comes in the box, other consumers may be interested in the added vitamins, and still other consumers may be interested in the type of grains. Associating these specific needs with consumers in a particular demographic group could be difficult. Marketing professionals want to know why consumers behave the way they do, what is of high priority to them, or how they rank the importance of specific buying criteria. Think about some of your friends who seem a lot like you. Have you ever gone to their homes and been shocked by their lifestyles and how vastly different they are from yours? Why are their families so much different from yours?

Psychographic segmentation can help fill in some of the blanks. Psychographic information is frequently gathered via extensive surveys that ask people about their activities, interests, opinion, attitudes, values, and lifestyles. One of the most well-known psychographic surveys is VALS (which originally stood for “Values, Attitudes, and Lifestyles”) and was developed by a company called SRI International in the late 1980s. SRI asked thousands of Americans the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with questions similar to the following: “My idea of fun at a national park would be to stay at an expensive lodge and dress up for dinner” and “I could stand to skin a dead animal” (Donnelly, 2002).

Hybrid Segmentation

Hybrid or Universal segmentation looks for similarities across world markets. This strategy solves the disadvantages of using macro- and micro-segmentation bases to segment international markets, as they tend to ignore similarities and highlight only the differences. Certain segments identified in a micro-segmentation strategy may have the same characteristics present on a global scale. One such segment is the Global Teen segment – young people between the ages of 12 and 19. It is likely that a group of teenagers randomly chosen from different parts of the world share many of the same tastes. Another such global segment is the Global Elite segment, comprising affluent consumers who have the money to spend on prestigious products with an image of exclusivity. The global elite segment can be associated with older individuals who have accumulated wealth over the course of a long career, including movie stars, musicians, athletes, and people who have achieved financial success at a relatively young age.

Hybrid segmentation involves looking for similarities across micro–segments identified in the countries selected in the final step of the CAA procedure. Under this process, country borders are honorary, as the segmentation process considers the countries selected in the final step of the CAA procedure as one market and searches for similar segments across these countries.

SOURCES

(1) “Generation Y Lacking Savings,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, September 13, 2009, 2D.

(2) “Telecommunications Marketing Opportunities to Ethnic Groups: Segmenting Consumer Markets by Ethnicity, Age, Income and Household Buying Patterns, 1998–2003,” The Insight Research Corporation, 2003, http://www.insight-corp.com/reports/ethnic.asp (accessed December 2, 2009).

(3) “Bluetooth Proximity Marketing,” April 24, 2007, http://bluetomorrow.com/bluetooth-articles/marketingtechnologies/bluetooth-proximity-marketing.html (accessed December 2, 2009).

(4) “U.S. Framework and VALS™ Type,” Strategic Business Insights, http://www.strategicbusinessinsights.com/vals/ustypes.shtml (accessed December 2, 2009).

REFERENCES

Barry, T., Mary Gilly, and Lindley Doran, “Advertising to Women with Different Career Orientations,” Journal of Advertising Research 25 (April–May 1985): 26–35.

Berkowitz, E. N., The Essentials of Health Care Marketing, 2nd ed. (Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett Publishers, 2006), 13.

Cox, B., “GM Hopes Its New Managers Will Energize It,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, August 29, 2009, 1C–4C.

Donnelly, J. H., preface to Marketing Management, 9th ed., by J. Paul Peter (New York: McGraw-Hill Professional, 2002), 79.

Harrison, M., Paul Hague, and Nick Hague, “Why Is Business-to-Business Marketing Special?”(whitepaper), B2B International, http://www.b2binternational.com/library/whitepapers/whitepapers04.php (accessed January 27, 2010).

Hill, B. J., Carey McDonald, and Muzzafer Uysal, “Resort Motivations for Different Family Life Cycle Stages,” Visions in Leisure and Business Number 8, no. 4 (1990): 18–27.

Miller R. K. and Kelli Washington, The 2009 Entertainment, Media & Advertising Market Research Handbook, 10th ed. (Loganville, GA: Richard K. Miller & Associates, 2009), 157–66.

Nee, E., “Due Diligence: The Customer Is Always Right,” CIO Insight, May 23, 2003.

Reisenwitz, T., Rajesh Iyer, David B. Kuhlmeier, and Jacqueline K. Eastman, “The Elderly’s Internet Usage: An Updated Look,” Journal of Consumer Marketing, 24, no. 7 (2007): 406–18.

Schlacter, B., “Sugar-Sweetened Soda Is Back in the Mainstream,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, April 22, 2009, 1C, 5C.

Tornoe, J. G., “Hispanic Marketing Basics: Segmentation of the Hispanic Market,” January 18, 2008, http://learn.latpro.com/segmentation-of-the-hispanic-market/ (accessed December 2, 2009).

von Hoffman, C., “For Some Marketers, Low Income Is Hot,” Brandweek, September 11, 2006, http://cfsinnovation.com/content/some-marketers-low-income-hot (accessed December 2, 2009).