8.2 Group Dynamics

Learning Objectives

- Understand the difference between informal and formal groups.

- Learn the stages of group development.

- Identify examples of the punctuated equilibrium model.

- Learn how group cohesion affects groups.

- Learn how social loafing affects groups.

- Learn how collective efficacy affects groups.

Types of Groups: Formal and Informal

What is a group? A group is a collection of individuals who interact with each other such that one person’s actions have an impact on the others. How groups function in organizations important implications for organizational productivity. Groups in which members respect one another, feel the desire to contribute to the team, and are capable of coordinating their efforts may have high performance levels, whereas teams characterized by extreme levels of conflict or hostility may demoralize members of the workforce.

In organizations, you may encounter different types of groups. Informal work groups are made up of two or more individuals who are associated with one another in ways not prescribed by the formal organization. For example, a few people in the company who get together to play tennis on the weekend would be considered an informal group. A formal work group is made up of employees who mutually influence and interact regularly with one another on work-related matters. We will discuss many different types of formal work groups later on in this chapter. We will also distinguish groups from teams.

Stages of Group Development

Forming, Storming, Norming, and Performing

American organizational psychologist Bruce Tuckman presented a robust model in 1965 that is still widely used today. Based on his observations of group behavior in a variety of settings, he proposed a four-stage map of group evolution, also known as the forming-storming-norming-performing model (Tuckman, 1965). Later he enhanced the model by adding a fifth and final stage, the adjourning phase. Interestingly enough, just as an individual moves through developmental stages such as childhood, adolescence, and adulthood, so does a group, although in a much shorter period of time. According to this theory, in order to successfully facilitate a group, the leader needs to move through various leadership styles over time. Generally, this is accomplished by first being more directive, eventually serving as a coach, and later, once the group is able to assume more power and responsibility for itself, shifting to a delegator. While research has not confirmed that this is descriptive of how groups progress, knowing and following these steps can help groups be more effective. For example, groups that do not go through the storming phase early on will often return to this stage toward the end of the group process to address unresolved issues. Another example of the validity of the group development model involves groups that take the time to get to know each other socially in the forming stage. When this occurs, groups tend to handle future challenges better because the individuals have an understanding of each other’s needs.

Forming

In the forming stage, the group comes together for the first time. The members may already know each other or they may be total strangers. In either case, there is a level of formality, some anxiety, and a degree of guardedness as group members are not sure what is going to happen next. “Will I be accepted? What will my role be? Who has the power here?” These are some of the questions participants think about during this stage of group formation. Because of the large amount of uncertainty, members tend to be polite, observant, and avoid conflict. They are trying to figure out the “rules of the game” without being too vulnerable. At this point, they may also be quite excited and optimistic about the task at hand, perhaps experiencing a level of pride at being chosen to join this particular group. Group members are trying to achieve several goals at this stage, although this may not necessarily be aware of it. First, they are trying to get to know each other. Often this can be accomplished by finding some common ground. Members also begin to explore group boundaries to determine what will be considered acceptable behavior. “Can I interrupt? Can I leave when I feel like it?” This trial phase may also involve testing the appointed leader or seeing if an informal leader emerges in groups in which no leader is assigned. At this point, group members are also discovering how the group will work in terms of what needs to be done and who will be responsible for each task. This stage is often characterized by abstract discussions about issues to be addressed by the group; those who like to get moving can become impatient with this part of the process. This phase is usually short in duration, perhaps a meeting or two.

Storming

Once group members feel sufficiently safe and included, they tend to enter the storming phase. Participants focus less on keeping their guard up as they shed social facades, becoming more authentic and more argumentative. Group members begin to explore their power and influence, and they often stake out their territory by differentiating themselves from the other group members rather than seeking common ground. Discussions can become heated as participants raise contending points of view and values, or argue over how tasks should be done and who is assigned to them. It is not unusual for group members to become defensive, competitive, or jealous. They may even take sides or begin to form cliques within the group. Questioning and resisting direction from the leader is also quite common. “Why should I have to do this? Who designed this project in the first place? Why do I have to listen to you?” Although little seems to get accomplished at this stage, group members are becoming more authentic as they express their deeper thoughts and feelings. What they are really exploring is “Can I truly be me, have power, and be accepted?” During this chaotic stage, a great deal of creative energy that was previously buried is released and available for use, but it takes skill to move the group on from the storming phase. In many cases, the group gets stuck in the storming phase.

OB Toolbox: Avoid Getting Stuck in the Storming Phase!

There are several steps you can take to avoid getting stuck in the storming phase of group development. Try the following if you feel the group process you are involved in is not progressing:

- Normalize conflict. Let members know this is a natural phase in the group-formation process. Ensure conflict is about the task, avoid any personal attacks.

- Be inclusive. Continue to make all members feel included and invite all views into the room. Mention how diverse ideas and opinions help foster creativity and innovation.

- Make sure everyone is heard. Facilitate heated discussions and help participants understand each other.

- Support all group members. This is especially important for those who feel more insecure.

- Remain positive. This is a key point to remember about the group’s ability to accomplish its goal.

- Don’t rush the group’s development. Remember that working through the storming stage can take several meetings.

Once group members discover that they can be authentic and that the group is capable of handling differences without dissolving, they are ready to enter the next stage, norming.

Norming

“We survived!” is the common sentiment at the norming stage. Group members often feel elated at this point, and they are much more committed to each other and the group’s goal. Feeling energized by knowing they can handle the “tough stuff,” group members are now ready to get to work. Finding themselves more cohesive and cooperative, participants find it easy to establish their own ground rules (or norms) and define their operating procedures and goals. The group tends to make big decisions, while subgroups or individuals handle the smaller decisions. By this point, the group should be open with and have respect for one another, and members ask each other for both help and feedback. They may even begin to form friendships and share more personal information with each other. At this point, the leader should become more of a facilitator by stepping back and letting the group assume more responsibility for its goal. Since the group’s energy is running high, this is an ideal time to host a social or team-building event.

Performing

Galvanized by a sense of shared vision and a feeling of unity, the group has now shifted into high gear. Members are more interdependent, individuality and differences are respected, and group members feel themselves to be part of a greater entity. At the performing stage, participants are not only getting the work done, but they also pay greater attention to how they are doing it. They ask questions like, “Do our operating procedures best support productivity and quality assurance? Do we have suitable means for addressing differences that arise so we can preempt destructive conflicts? Are we relating to and communicating with each other in ways that enhance group dynamics and help us achieve our goals? How can I further develop as a person to become more effective?” By now, the group has matured, becoming more competent, autonomous, and insightful. Group leaders can finally move into coaching roles and help members grow in skill and leadership.

Adjourning

Just as groups form, so do they end. For example, many groups or teams formed in a business context are project oriented and therefore are temporary in nature. Alternatively, a working group may dissolve due to an organizational restructuring. Just as when we graduate from school or leave home for the first time, these endings can be bittersweet, with group members feeling a combination of victory, grief, and insecurity about what is coming next. For those who like routine and bond closely with fellow group members, this transition can be particularly challenging. Group leaders and members alike should be sensitive to handling these endings respectfully and compassionately. An ideal way to close a group is to set aside time to debrief (“How did it all go? What did we learn?”), acknowledge each other, and celebrate a job well done. As a team leader/facilitator, you might also consider following up again with the group six months or a year later. Sometimes, time is needed for reflecting on lessons learned, and those after-the-fact insights can help people with their future group work.

The Punctuated-Equilibrium Model

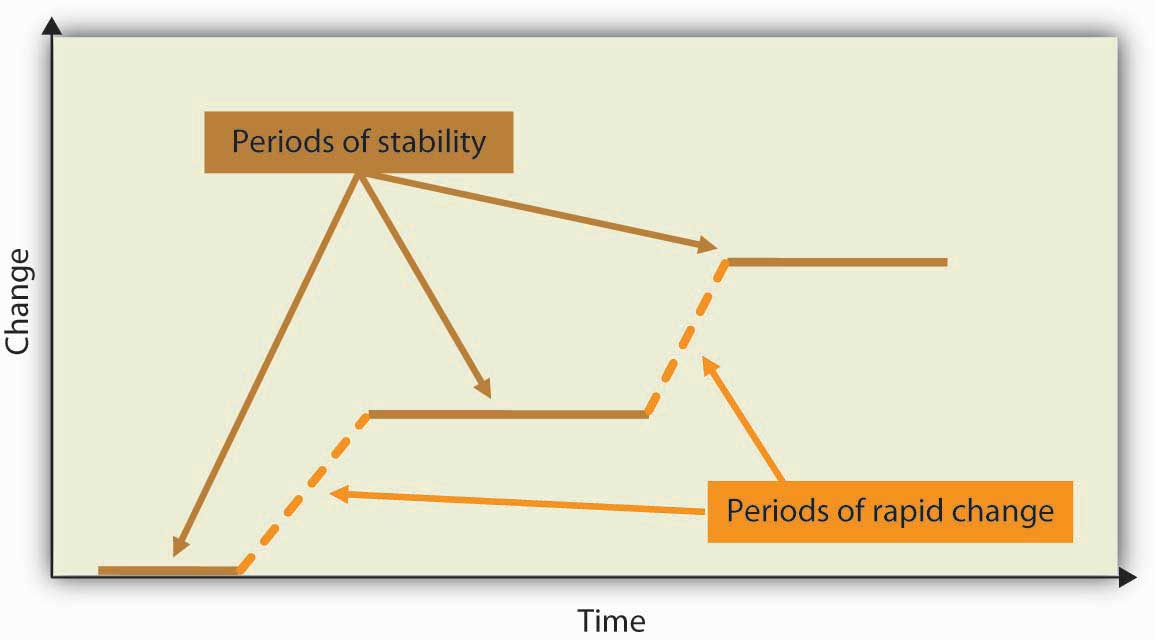

As you may have noted, the five-stage model we have just reviewed is meant to be a linear process. According to the model, a group progresses to the performing stage, at which point it finds itself in an ongoing, smooth-sailing situation until the group dissolves. In reality, subsequent researchers, most notably Joy H. Karriker, have found that the life of a group is much more dynamic and cyclical in nature (Karriker, 2005). For example, a group may operate in the performing stage for several months. Then, because of a disruption, such as a competing emerging technology that changes the rules of the game or the introduction of a new CEO, the group may revert back to the storming phase before returning to performing. Ideally, any regression in the linear group progression will ultimately result in a higher level of functioning. Proponents of this cyclical model draw from behavioral scientist Connie Gersick’s study of punctuated equilibrium (Gersick, 1991).

The concept of punctuated equilibrium was first proposed in 1972 by paleontologists Niles Eldredge and Stephen Jay Gould, who both believed that evolution occurred in rapid, radical spurts rather than gradually over time. Identifying numerous examples of this pattern in social behavior, Gersick found that the concept also applied to organizational change. She proposed that groups remain fairly static, maintaining a certain equilibrium for long periods of time. Change during these periods is incremental, largely due to the resistance to change that arises when systems take root and processes become institutionalized. In this model, revolutionary change occurs in brief, punctuated bursts, generally catalyzed by a crisis or problem that breaks through the systemic inertia and shakes up the deep organizational structures in place. At this point, the organization or group has the opportunity to learn and create new structures that are better aligned with current realities. Whether the group does this is not guaranteed. In sum, in Gersick’s model, groups can repeatedly cycle through the storming and performing stages, with revolutionary change taking place during short transitional windows. For organizations and groups who understand that disruption, conflict, and chaos are inevitable in the life of a social system, these disruptions represent opportunities for innovation and creativity.

Cohesion

Cohesion can be thought of as a kind of social glue. It refers to the degree of camaraderie within the group. Cohesive groups are those in which members are attached to each other and act as one unit. Generally speaking, the more cohesive a group is, the more productive it will be and the more rewarding the experience will be for the group’s members (Beal et al., 2003; Evans & Dion, 1991). Members of cohesive groups tend to have the following characteristics: They have a collective identity; they experience an emotional bond and a desire to remain part of the group; they share a sense of purpose, working together on a meaningful task or cause; and they establish a structured pattern of communication.

The fundamental factors affecting group cohesion include the following:

- Similarity. Generally, the more similar group members are in terms of age, sex, education, skills, attitudes, values, and beliefs, the more easily and quickly the group will bond. However, groups that work hard to create cohesion in spite of significant differences can enjoy especially deep bonds.

- Stability. The longer a group stays together, the more cohesive it becomes.

- Size. Smaller groups tend to have higher levels of cohesion.

- Support. When group members receive coaching and are encouraged to support their fellow team members, group identity strengthens.

- Satisfaction. Cohesion is correlated with how pleased group members are with each other’s performance, behavior, and conformity to group norms.

As you might imagine, there are many benefits in creating a cohesive group. Members are generally more personally satisfied and feel greater self-confidence and self-esteem when in a group where they feel they belong. For many, membership in such a group can be a buffer against stress, which can improve mental and physical well-being. Because members are invested in the group and its work, they are more likely to regularly attend and actively participate in the group, taking more responsibility for the group’s functioning. In addition, members can draw on the strength of the group to persevere through challenging situations that might otherwise be too hard to tackle alone.

OB Toolbox: Steps to Creating and Maintaining a Cohesive Team

- Align the group with the greater organization. Establish common objectives in which members can get involved.

- Let members have choices in setting their own goals. Include them in decision making at the organizational level.

- Define clear roles. Demonstrate how each person’s contribution furthers the group goal—everyone is responsible for a special piece of the puzzle.

- Situate group members in close proximity to each other. This builds familiarity.

- Give frequent praise. Both individuals and groups benefit from praise. Also encourage them to praise each other. This builds individual self-confidence, reaffirms positive behavior, and creates an overall positive atmosphere.

- Treat all members with dignity and respect. This demonstrates that there are no favorites and everyone is valued.

- Celebrate differences. This highlights each individual’s contribution while also making diversity a norm.

- Establish common rituals. Thursday morning coffee, monthly potlucks—these reaffirm group identity and create shared experiences.

Can a Group Have Too Much Cohesion?

Keep in mind that groups can have too much cohesion. Because members can come to value belonging over all else, an internal pressure to conform may arise, causing some members to modify their behavior to adhere to group norms. Members may become conflict avoidant, focusing more on trying to please each other so as not to be ostracized. In some cases, members might censor themselves to maintain the party line. As such, there is a superficial sense of harmony and less diversity of thought. Having less tolerance for deviants, who threaten the group’s static identity, cohesive groups will often excommunicate members who dare to disagree. Members attempting to make a change may even be criticized or undermined by other members, who perceive this as a threat to the status quo. The painful possibility of being marginalized can keep many members in line with the majority.

The more strongly members identify with the group, the easier it is to see outsiders as inferior, or enemies in extreme cases, which can lead to increased insularity. This form of prejudice can have a downward spiral effect. Not only is the group not getting corrective feedback from within its own confines, it is also closing itself off from input and a cross-fertilization of ideas from the outside. In such an environment, groups can easily adopt extreme ideas that will not be challenged. Denial increases as problems are ignored and failures are blamed on external factors. With limited, often biased, information and no internal or external opposition, groups like these can make disastrous decisions. Groupthink is a group pressure phenomenon that increases the risk of the group making flawed decisions by allowing reductions in mental efficiency, reality testing, and moral judgment. Groupthink is most common in highly cohesive groups (Janis, 1972).

Cohesive groups can go awry in much milder ways. For example, group members can value their social interactions so much that they have fun together but spend little time on accomplishing their assigned task. Or a group’s goal may begin to diverge from the larger organization’s goal and those trying to uphold the organization’s goal may be ostracized (e.g., teasing the class “brain” for doing well in school). Normalizing conflict and even encouraging it (e.g., by assigning a group member to the “devil’s advocate” role each meeting) can provide a safer environment for disagreements.

In addition, research shows that cohesion leads to acceptance of group norms (Goodman, Ravlin, & Schminke, 1987). Groups with high task commitment do well, but imagine a group where the norms are to work as little as possible? As you might imagine, these groups get little accomplished and can actually work together against the organization’s goals.

Social Loafing

Social loafing refers to the tendency of individuals to put in less effort when working in a group context. This phenomenon, also known as the Ringelmann effect, was first noted by French agricultural engineer Max Ringelmann in 1913. In one study, he had people pull on a rope individually and in groups. He found that as the number of people pulling increased, individuals reduced their own effort so that the benefits of more people were not realized (Karau & Williams, 1993).

Why do people work less hard when they are working with other people? Observations show that as the size of the group grows, this effect becomes larger as well (Karau & Williams, 1993). The social loafing tendency is less a matter of being lazy and more a matter of perceiving that one will receive neither one’s fair share of rewards if the group is successful nor blame if the group fails. Rationales for this behavior include, “My own effort will have little effect on the outcome,” “Others aren’t pulling their weight, so why should I?” or “I don’t have much to contribute, but no one will notice anyway.” This is a consistent effect across a great number of group tasks and countries (Gabrenya, Latane, & Wang, 1983; Harkins & Petty, 1982; Taylor & Faust, 1952; Ziller, 1957). Research also shows that perceptions of fairness are related to less social loafing (Price, Harrison, & Gavin, 2006). Therefore, teams that are deemed as more fair should also see less social loafing.

OB Toolbox: Tips for Preventing Social Loafing in Your Group

When designing a group project, here are some considerations to keep in mind:

- Carefully choose the number of individuals you need to get the task done. The likelihood of social loafing increases as group size increases (especially if the group consists of 10 or more people), because it is easier for people to feel unneeded or inadequate, and it is easier for them to “hide” in a larger group.

- Clearly define each member’s tasks in front of the entire group. If you assign a task to the entire group, social loafing is more likely. For example, instead of stating, “By Monday, let’s find several articles on the topic of stress,” you can set the goal of “By Monday, each of us will be responsible for finding five articles on the topic of stress.” When individuals have specific goals, they become more accountable for their performance.

- Design and communicate to the entire group a system for evaluating each person’s contribution. You may have a midterm feedback session in which each member gives feedback to every other member. This would increase the sense of accountability individuals have. You may even want to discuss the principle of social loafing in order to discourage it.

- Build a cohesive group. When group members develop strong relational bonds, they are more committed to each other and the success of the group, and they are therefore more likely to pull their own weight.

- Assign tasks that are highly engaging and inherently rewarding. Design challenging, unique, and varied activities that will have a significant impact on the individuals themselves, the organization, or the external environment. For example, one group member may be responsible for crafting a new incentive-pay system through which employees can direct some of their bonus to their favorite nonprofits.

- Make sure individuals feel that they are needed. If the group ignores a member’s contributions because these contributions do not meet the group’s performance standards, members will feel discouraged and are unlikely to contribute in the future. Make sure that everyone feels included and needed by the group.

Collective Efficacy

Collective efficacy refers to a group’s perception of its ability to successfully perform well (Bandura, 1997). Collective efficacy is influenced by a number of factors, including watching others (“that group did it and we’re better than them”), verbal persuasion (“we can do this”), and how a person feels (“this is a good group”). Research shows that a group’s collective efficacy is related to its performance (Gully et al., 2002; Porter, 2005; Tasa, Taggar, & Seijts, 2007). In addition, this relationship is higher when task interdependence (the degree an individual’s task is linked to someone else’s work) is high rather than low.

Key Takeaway

Groups may be either formal or informal. Groups go through developmental stages much like individuals do. The forming-storming-norming-performing-adjourning model is useful in prescribing stages that groups should pay attention to as they develop. The punctuated-equilibrium model of group development argues that groups often move forward during bursts of change after long periods without change. Groups that are similar, stable, small, supportive, and satisfied tend to be more cohesive than groups that are not. Cohesion can help support group performance if the group values task completion. Too much cohesion can also be a concern for groups. Social loafing increases as groups become larger. When collective efficacy is high, groups tend to perform better.

References

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Beal, D. J., Cohen, R. R., Burke, M. J., & McLendon, C. L. (2003). Cohesion and performance in groups: A meta-analytic clarification of construct relations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 989–1004.

Evans, C. R., & Dion, K. L. (1991). Group cohesion and performance: A meta-analysis. Small Group Research, 22, 175–186.

Gabrenya, W. L., Latane, B., & Wang, Y. (1983). Social loafing in cross-cultural perspective. Journal of Cross-Cultural Perspective, 14, 368–384.

Gersick, C. J. G. (1991). Revolutionary change theories: A multilevel exploration of the punctuated equilibrium paradigm. Academy of Management Review, 16, 10–36.

Goodman, P. S., Ravlin, E., & Schminke, M. (1987). Understanding groups in organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior, 9, 121–173.

Gully, S. M., Incalcaterra, K. A., Joshi, A., & Beaubien, J. M. (2002). A meta-analysis of team-efficacy, potency, and performance: Interdependence and level of analysis as moderators of observed relationships. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 819–832.

Harkins, S., & Petty, R. E. (1982). Effects of task difficulty and task uniqueness on social loafing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43, 1214–1229.

Janis, I. L. (1972). Victims of Groupthink. New York: Houghton Mifflin.

Karau, S. J., & Williams, K. D. (1993). Social loafing: A meta-analytic review and theoretical integration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65, 681–706.

Karriker, J. H. (2005). Cyclical group development and interaction-based leadership emergence in autonomous teams: An integrated model. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 11, 54–64.

Porter, C. O. L. H. (2005). Goal orientation: Effects on backing up behavior, performance, efficacy, and commitment in teams. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 811–818.

Price, K. H., Harrison, D. A., & Gavin, J. H. (2006). Withholding inputs in team contexts: Member composition, interaction processes, evaluation structure, and social loafing. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 1375–1384.

Tasa, K., Taggar, S., & Seijts, G. H. (2007). The development of collective efficacy in teams: A multilevel and longitudinal perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 17–27.

Taylor, D. W., & Faust, W. L. (1952). Twenty questions: Efficiency of problem-solving as a function of the size of the group. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 44, 360–363.

Tuckman, B. (1965). Developmental sequence in small groups. Psychological Bulletin, 63, 384–399.

Ziller, R. C. (1957). Four techniques of group decision-making under uncertainty. Journal of Applied Psychology, 41, 384–388.