6.5 Motivating Employees Through Performance Incentives

Learning Objectives

- Learn the importance of financial and nonfinancial incentives to motivate employees.

- Understand the benefits of different types of incentive systems, such as piece rate and merit pay.

- Learn why nonfinancial incentives can be effective motivators.

- Understand the tradeoffs involved in rewarding individual, group, and organizational performance.

Performance Incentives

Perhaps the most tangible way in which companies put motivation theories into action is by instituting incentive systems. Incentives are reward systems that tie pay to performance. There are many incentives used by companies, some tying pay to individual performance and some to companywide performance. Pay-for-performance plans are very common among organizations. For example, according to one estimate, 80% of all American companies have merit pay, and the majority of Fortune 1000 companies use incentives (Luthans & Stajkovic, 1999). Using incentives to increase performance is a very old idea. For example, Napoleon promised 12,000 francs to whoever found a way to preserve food for the army. The winner of the prize was Nicolas Appert, who developed a method of canning food (Vision quest, 2008). Research shows that companies using pay-for-performance systems actually achieve higher productivity, profits, and customer service. These systems are more effective than praise or recognition in increasing retention of higher performing employees by creating higher levels of commitment to the company (Cadsby, Song, & Tapon, 2007; Peterson & Luthans, 2006; Salamin & Hom, 2005). Moreover, employees report higher levels of pay satisfaction under pay-for-performance systems (Heneman, Greenberger, & Strasser, 1988).

At the same time, many downsides of incentives exist. For example, it has been argued that incentives may create a risk-averse environment that diminishes creativity. This may happen if employees are rewarded for doing things in a certain way, and taking risks may negatively affect their paycheck. Moreover, research shows that incentives tend to focus employee energy to goal-directed efforts, and behaviors such as helping team members or being a good citizen of the company may be neglected (Breen, 2004; Deckop, Mengel, & Cirka, 1999; Wright et al., 1993). Despite their limitations, financial incentives may be considered powerful motivators if they are used properly and if they are aligned with companywide objectives. The most frequently used incentives are listed as follows.

Piece Rate Systems

Under piece rate incentives, employees are paid on the basis of individual output they produce. For example, a manufacturer may pay employees based on the number of purses sewn or number of doors installed in a day. In the agricultural sector, fruit pickers are often paid based on the amount of fruit they pick. These systems are suitable when employee output is easily observable or quantifiable and when output is directly correlated with employee effort. Piece rate systems are also used in white-collar jobs such as check-proofing in banks. These plans may encourage employees to work very fast, but may also increase the number of errors made. Therefore, rewarding employee performance minus errors might be more effective. Today, increases in employee monitoring technology are making it possible to correctly measure and observe individual output. For example, technology can track the number of tickets an employee sells or the number of customer complaints resolved, allowing a basis for employee pay incentives (Conlin, 2002). Piece rate systems can be very effective in increasing worker productivity. For example, Safelite AutoGlass, a nationwide installer of auto glass, moved to a piece rate system instead of paying workers by the hour. This change led to an average productivity gain of 20% per employee (Koretz, 1997).

Individual Bonuses

Bonuses are one-time rewards that follow specific accomplishments of employees. For example, an employee who reaches the quarterly goals set for her may be rewarded with a lump sum bonus. Employee motivation resulting from a bonus is generally related to the degree of advanced knowledge regarding bonus specifics.

Merit Pay

In contrast to bonuses, merit pay involves giving employees a permanent pay raise based on past performance. Often the company’s performance appraisal system is used to determine performance levels and the employees are awarded a raise, such as a 2% increase in pay. One potential problem with merit pay is that employees come to expect pay increases. In companies that give annual merit raises without a different raise for increases in cost of living, merit pay ends up serving as a cost-of-living adjustment and creates a sense of entitlement on the part of employees, with even low performers expecting them. Thus, making merit pay more effective depends on making it truly dependent on performance and designing a relatively objective appraisal system.

Figure 6.9

Properly designed sales commissions are widely used to motivate sales employees. The blend of straight salary and commissions should be carefully balanced to achieve optimum sales volume, profitability, and customer satisfaction.

Rossbeane – the bike shop – CC BY-SA 2.0.

Sales Commissions

In many companies, the paycheck of sales employees is a combination of a base salary and commissions. Sales commissions involve rewarding sales employees with a percentage of sales volume or profits generated. Sales commissions should be designed carefully to be consistent with company objectives. For example, employees who are heavily rewarded with commissions may neglect customers who have a low probability of making a quick purchase. If only sales volume (as opposed to profitability) is rewarded, employees may start discounting merchandise too heavily, or start neglecting existing customers who require a lot of attention (Sales incentive plans, 2006). Therefore, the blend of straight salary and commissions needs to be managed carefully.

Awards

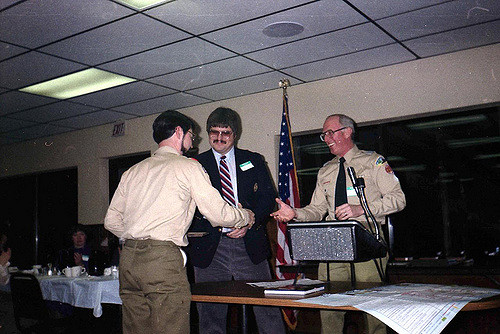

Figure 6.10

Plaques and other recognition awards may motivate employees if these awards fit with the company culture and if they reflect a sincere appreciation of employee accomplishments.

Steve B – Scenic District Recognition Banquet 1985 – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Some companies manage to create effective incentive systems on a small budget while downplaying the importance of large bonuses. It is possible to motivate employees through awards, plaques, or other symbolic methods of recognition to the degree these methods convey sincere appreciation for employee contributions. For example, Yum! Brands Inc. recognizes employees who go above and beyond job expectations through creative awards such as the seat belt award (a seat belt on a plaque), symbolizing the roller-coaster-like, fast-moving nature of the industry. Other awards include things such as a plush toy shaped like a jalapeño pepper. Hewlett-Packard has the golden banana award, which came about when a manager wanted to reward an employee who solved an important problem on the spot and handed him a banana lying around the office. Later, the golden banana award became an award bestowed on the most innovative employees (Nelson, 2009). Another alternative way of recognizing employee accomplishments is awarding gift cards. These awards may help create a sense of commitment to the company by creating positive experiences that are attributed to the company.

Team Bonuses

In situations in which employees should cooperate with each other and isolating employee performance is more difficult, companies are increasingly resorting to tying employee pay to team performance. For example, Wal-Mart has a history of giving bonuses to around 80% of their associates based on store performance. If employees have a reasonable ability to influence their team’s performance level, these programs may be effective.

Gainsharing

Gainsharing is a companywide program in which employees are rewarded for performance gains compared to past performance. These gains may take the form of reducing labor costs compared to estimates or reducing overall costs compared to past years’ figures. These improvements are achieved through employee suggestions and participation in management through employee committees. For example, Premium Standard Farms LLC, a meat processing plant, instituted a gainsharing program in which employee-initiated changes in production processes led to a savings of $300,000 a month. The bonuses were close to $1,000 per person. These programs can be successful if the payout formula is generous, employees can truly participate in the management of the company, and if employees are able to communicate and execute their ideas (Balu & Kirchenbaum, 2000; Collins, Hatcher, & Ross, 1993; Imberman, 1996).

Profit Sharing

Profit sharing programs involve sharing a percentage of company profits with all employees. These programs are company-wide incentives and are not very effective in tying employee pay to individual effort, because each employee will have a limited role in influencing company profitability. At the same time, these programs may be more effective in creating loyalty and commitment to the company by recognizing all employees for their contributions throughout the year.

Stock Options

A stock option gives an employee the right, but not the obligation, to purchase company stocks at a predetermined price. For example, a company would commit to sell company stock to employees or managers 2 years in the future at $30 per share. If the company’s actual stock price in 2 years is $60, employees would make a profit by exercising their options at $30 and then selling them in the stock market. The purpose of stock options is to align company and employee interests by making employees owners. However, options are not very useful for this purpose, because employees tend to sell the stock instead of holding onto it. In the past, options were given to a wide variety of employees, including CEOs, high performers, and in some companies all employees. For example, Starbucks Corporation was among companies that offered stock to a large number of associates. Options remain popular in start-up companies that find it difficult to offer competitive salaries to employees. In fact, many employees in high-tech companies such as Microsoft and Cisco Systems Inc. became millionaires by cashing in stock options after these companies went public. In recent years, stock option use has declined. One reason for this is the changes in options accounting. Before 2005, companies did not have to report options as an expense. After the changes in accounting rules, it became more expensive for companies to offer options. Moreover, options are less attractive or motivational for employees when the stock market is going down, because the cost of exercising their options may be higher than the market value of the shares. Because of these and other problems, some companies started granting employees actual stock or using other incentives. For example, PepsiCo Inc. replaced parts of the stock options program with a cash incentive program and gave managers the choice of getting stock options coupled with restricted stocks (Brandes et al., 2003; Rafter, 2004; Marquez, 2005).

Key Takeaway

Companies use a wide variety of incentives to reward performance. This is consistent with motivation theories showing that rewarded behavior is repeated. Piece rate, individual bonuses, merit pay, and sales commissions tie pay to individual performance. Team bonuses are at the department level, whereas gainsharing, profit sharing, and stock options tie pay to company performance. While these systems may be effective, people tend to demonstrate behavior that is being rewarded and may neglect other elements of their performance. Therefore, reward systems should be designed carefully and should be tied to a company’s strategic objectives.

References

Balu, R., & Kirchenbaum, J. (2000, December). Bonuses aren’t just for bosses. Fast Company, 41, 74–76.

Brandes, P., Dharwadkar, R., Lemesis, G. V., & Heisler, W. J. (2003, February). Effective employee stock option design: Reconciling stakeholder, strategic, and motivational factors. Academy of Management Executive, 17, 77–93.

Breen, B. (2004, December). The 6 myths of creativity. Fast Company, 75–78.

Cadsby, C. B., Song, F., & Tapon, F. (2007). Sorting and incentive effects of pay for performance: An experimental investigation. Academy of Management Journal, 50, 387–405.

Collins, D., Hatcher, L., & Ross, T. L. (1993). The decision to implement gainsharing: The role of work climate, expected outcomes, and union status. Personnel Psychology, 46, 77–104.

Conlin, M. (2002, February 25). The software says you’re just average. Business Week, 126.

Deckop, J. R., Mengel, R., & Cirka, C. C. (1999). Getting more than you pay for: Organizational citizenship behavior and pay for performance plans. Academy of Management Journal, 42, 420–428.

Heneman, R. L., Greenberger, D. B., & Strasser, S. (1988). The relationship between pay-for-performance perceptions and pay satisfaction. Personnel Psychology, 41, 745–759.

Imberman, W. (1996, January–February). Gainsharing: A lemon or lemonade? Business Horizons, 39, 36.

Koretz, G. (1997, February 17). Truly tying pay to performance. Business Week, 25.

Luthans, F., & Stajkovic, A. D. (1999). Reinforce for performance: The need to go beyond pay and even rewards. Academy of Management Executive, 13, 49–57.

Marquez, J. (2005, September). Firms replacing stock options with restricted shares face a tough sell to employees. Workforce Management, 84, 71–73.

Nelson, B. (2009). Secrets of successful employee recognition. Retrieved November 23, 2008, from http://www.qualitydigest.com/aug/nelson.html; Sittenfeld, C. (2004, January). Great job! Here’s a seat belt! Fast Company, 29.

Peterson, S. J., & Luthans, F. (2006). The impact of financial and nonfinancial incentives on business-unit outcomes over time. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 156–165.

Rafter, M. V. (2004, September). As the age of options wanes, companies settle on new incentive plans. Workforce Management, 83, 64–67.

Salamin, A., & Hom, P. W. (2005). In search of the elusive U-shaped performance-turnover relationship: Are high performing Swiss bankers more liable to quit? Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 1204–1216.

Sales incentive plans: 10 essentials. (2006, November 17). Business Week Online, 18. Retrieved on November 23, 2008, from http://businessweek.mobi/detail.jsp?key=3435&rc=as&p=1&pv=1.

Vision quest: Contests throughout history. (2008, May). Fast Company, 44–45.

Wright, P. M., George, J. M., Farnsworth, S. R., & McMahan, G. C. (1993). Productivity and extra-role behavior: The effects of goals and incentives on spontaneous helping. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78, 374–381.