47 5.3 CLASSIFICATION AND DISTRIBUTION OF LANGUAGES

This second section will facilitate your understanding of the dimensions of language across geographic areas and cultural landscapes. Three main questions are addressed in this section:

- How are languages classified with respect to issues of national identity and genealogical considerations?

- What are the major language families of the world and how many speakers make use of the respective languages?

- How does language use vary in the United States with respect to dialects of English and multilingualism?

5.3.1 Diffusion of Languages

Language, like any other cultural phenomenon, has an inherent spatiality, and all languages have a history of diffusion. As our ancestors moved from place to place, they brought their languages with them. As people have conquered other places, expanded demographically, or converted others to new religions, languages have moved across space. Writing systems that were developed by one people were adapted and used by others. Indo-European, the largest language family, spread across a large expanse of Europe and Asia through a mechanism that is still being debated. Later, European expansion produced much of the current linguistic map by spreading English, French, Spanish, Portuguese, and Russian far from their native European homelands.

Language is disseminated through diffusion, but in complex ways. Relocation diffusion is associated with settler colonies and conquest, but in many places, hierarchical diffusion is the form that best explains the predominant languages. People may be compelled to adopt a dominant language for social, political or economic mobility. Contagious diffusion is also seen in languages, particularly in the adoption of new expressions in a language. One of the most obvious examples has been in the current convergence of British and American English. The British press has published books1 and articles2 decrying the Americanization of British English, while the American press has done the same thing in reverse3. In reality, languages borrow bits and pieces from other languages continuously.

The establishment of official languages is often related to the linguistic power differential within countries. Russification and Arabization are just two implementations of processes that use political power to favor one language over another.

5.3.2 Classification of Languages

There is no precise figure as to the total number of languages spoken in the world today. Estimates vary between 5,000 and 7,000, and the accurate number depends partly on the arbitrary distinction between languages and dialects. Dialects (variants of the same language) reflect differences along regional and ethnic lines. In the case of English, most native speakers will agree that they are speakers of English even though differences in pronunciation, vocabulary and sentence structure clearly exist. English speakers from England, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and United States of America will generally agree that they speak English, and this is also confirmed with the use of a standard written form of the language and a common literary heritage. However, there are many other cases in which speakers will not agree when the question of national identity and mutual intelligibility do not coincide.

The most common situation is when similar spoken language varieties are mutually understandable, but for political and historical reasons, they are regarded as different languages as in the case of Scandinavian languages. While Swedes, Danes and Norwegians can communicate with each other in most instances, each national group admits speaking a different language: Swedish, Danish, Norwegian and Icelandic. There are other cases in which political, ethnic, religious, literary and other factors force a distinction between similar language varieties: Hindi vs. Urdu, Flemish vs. Dutch, Serbian vs. Croatian, Gallego vs. Portuguese, Xhosa vs Zulu. An opposite situation occurs when spoken language varieties are not mutually understood, but for political, historical or cultural motives, they are regarded as the same language as in the case of Lapp and Chinese dialects.

Languages are usually classified according to membership in a language family (a group of related languages) which share common linguistic features (pronunciation, vocabulary, grammar) and have evolved from a common ancestor (proto-language). This type of linguistic classification is known as the genetic or genealogical approach. Languages can also be classified according to sentence structure (S)ubject+(V)erb+(O)bject, S+O+V, V+S+O). This type of classification is known as typological classification, and is based on a comparison of the formal similarities (pronunciation, grammar or vocabulary) which exist among languages.

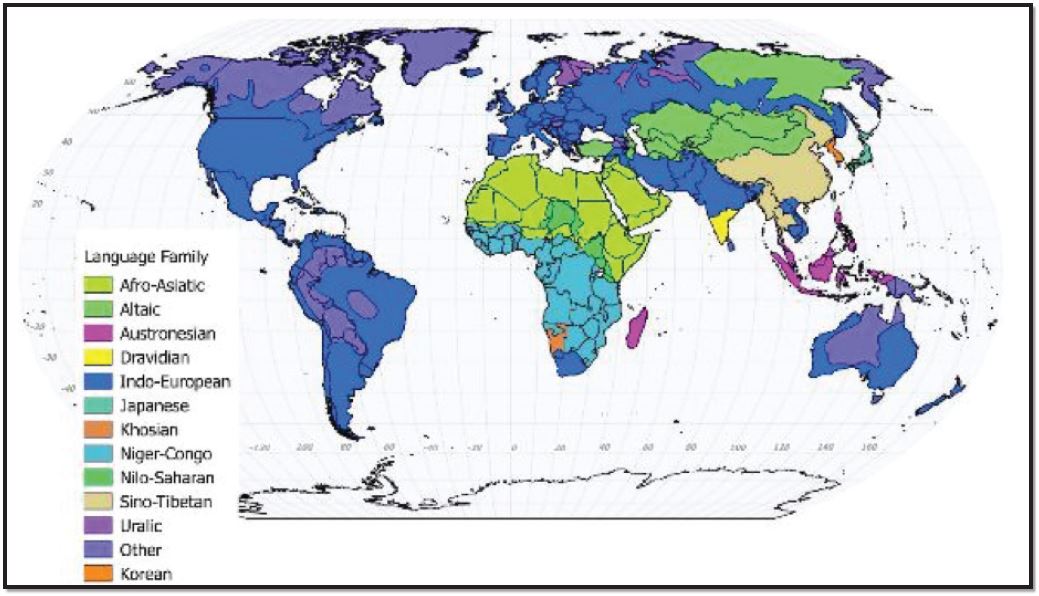

Language families around the world reflect centuries of geographic movement and interaction among different groups of people. The Indo-European family of languages, for example, represents nearly half of the world’s population. The language family dominates nearly all of Europe, significant areas of Asia, including Russia and India, North and South America, Caribbean islands, Australia, New Zealand, and parts of South Africa. The Indo-European family of languages consists of various language branches (a collection of languages within a family with a common ancestral language) and numerous language subgroups (a collection of languages within a branch that share a common origin in the relative recent past and exhibit many similarities in vocabulary and grammar.

Indo-European Language Branches and Language Subgroups

Germanic Branch

Western Germanic Group (Dutch, German, Frisian, English)

Northern Germanic Group (Danish, Swedish, Norwegian, Icelandic, Faeroese)

Romance Branch

French, Portuguese, Spanish, Catalan, Provençal, Romansh, Italian, Romanian)

Slavic Branch

West Slavic Group (Polish, Slovak, Czech, Sorbian)

Eastern Slavic Group (Russian, Ukrainian, Belorussian)

Southern Slavic Group (Slovene, Serbo-Croatian, Macedonian, Bulgarian)

Celtic Branch

Britannic Group (Breton, Welsh)

Gaulish Group (Irish Gaelic, Scots Gaelic)

Baltic-Slavonic Branch

Latvian, Lithuanian

Hellenic Branch

Greek

Thracian-Illyrian Branch

Albanian

Armenian Branch

Armenian

Iranian Branch

Kurdish, Persian, Baluchi, Pashto, Tadzhik

Indo-Iranian (Indic) Branch

Northwestern Group (Panjabi, Sindhi, Pahari, Dardic)

Eastern Group (Assamese, Bengali, Oriya)

Midland Group (Rajasthani, Hindi/Urdu, Bihari)

West and Southwestern Group (Gujarati, Marathi, Konda, Maldivian, Sinhalese)

Other languages spoken in Europe, but not belonging to the Indo-European family are subsumed in these other families: Finno-Ugric (Estonian, Hungarian, Karelian, Saami, Altaic (Turkish, Azerbaijani, Uzbek) and Basque. Some of the language branches listed above are represented by only one principal language (Albanian, Armenian, Basque, Greek), while others are spoken by diverse groups in some geographic regions (Northern and Western Germanic languages, Western and Eastern Slavic languages, Midland and Southwestern Indian languages).

Figure 5.1 | Language Families of the World4

Author | David Dorrell

Source | Original Work

License | CC BY SA 4.0

Major Language Families of the World by Geographic Region

Europe

Caucasian Family

Abkhaz-Adyghe Group (Circassian, Adyghe, Abkhaz)

Nakho-Dagestanian Group (Avar, Kuri, Dargwa)

Kartvelian Group (Kartvelian, Georgian, Zan, Mingrelian)

Africa

Afro-Asiatic Family (Arabic, Hebrew, Tigrinya, Amharic)

Niger-Congo Family (Benue-Congo, Adamawa, Kwa)

Nilo-Saharan Family (Chari-Nile, Nilo-Hamitic, Nara)

Khoisan Family (Sandawe, Hatsa)

Asia

Sino-Tibetan Family (Chinese, Tibetan, Burmese)

Tai Family (Laotian, Shan, Yuan)

Austro-Asiatic Family (Vietnamese, Indonesian, Dayak, Malayo-Polynesian)

Japanese (an example of an isolated language)

Pacific

Austronesian Family (Malagasy, Malay, Javanese, Palauan, Fijian)

Indo-Pacific Family (Tagalog, Maori, Tongan, Samoan)

Americas

Eskimo-Aleut Family (Eskimo-Aleut, Greenlandic Eskimo)

Athabaskan Family (Navaho. Apache)

Algonquian Family (Arapaho, Blackfoot, Cheyenne, Cree, Mohican, Choctaw)

Macro-Siouan Family (Cherokee, Dakota, Mohawk, Pawnee)

Aztec-Tanoan Family (Comanche, Hopi, Pima-Papago, Nahuatl, Tarahumara)

Mayan Family (Maya, Mam, Quekchi, Quiche)

Oto-Manguean Family (Otomi, Mixtec, Zapotec)

Macro-Chibchan Family (Guaymi, Cuna, Waica, Epera)

Andean-Equatorial Family (Guahibo, Aymara, Quechua, Guarani)

The number of language families distributed around the world is sizable. The linguistic situation of specific member groups of the language family might be influenced by diverse, interacting factors: settlement history (migration, conquest, colonialism, territorial agreements), ways of living (farming, fishing, hunting, trading) and demographic strength and vitality of the speaker groups. Some languages might converge (many local varieties becoming one main language), while others might diverge (one principal language evolves into many other speech varieties). When different linguistic groups come into contact, a pidgin type of language may be the result. A pidgin is a composite language with a simplified grammatical system and a limited vocabulary, typically borrowed from the linguistic groups involved in trade and commerce activities.

Tok Pisin is an example of a pidgin spoken in Papua New Guinea and derived mainly from English. A pidgin may become a creole language when the size of the vocabulary increases, grammatical structures become more complex and children learn it as their native language or mother tongue. There are cases in which one existing language gains the status of a lingua franca. A lingua franca may not necessarily be the mother tongue of any one speaker group, but it serves as the medium of communication and commerce among diverse language groups. Swahili, for instance, serves as a lingua franca for much of East Africa, where individuals speak other local and regional languages.

With increased globalization and interdependence among nations, English is rapidly acquiring the status of lingua franca for much of the world. In Europe, Africa and India and other geographic regions, English serves as a lingua franca across many national-state boundaries. The linguistic con- sequence results in countless numbers of speaker groups who must become bilingual (the ability to use two languages with varying degrees of fluency) to participate more fully in society.

Some continents have more spoken languages than others. Asia leads with an estimated 2,300 languages, followed by Africa with 2,138. In the Pacific area, there are about 1,300 languages spoken and in North and South America about 1,064 languages have been identified. Europe, even with its many nation-states, is at the bottom of the list with about 286 languages.

| Language | Family | Speakers in Millions | Main Areas Where Spoken |

| Chinese | Sino-Tibetan | 1197 | China, Taiwan, Singapore |

| Spanish | Indo-European | 406 | Spain, Latin America, Southwestern United States |

| English | Indo-European | 335 | British Isles, United States, Canada, Caribbean, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Philippines, former British colonies in Asia and Africa |

| Hindi | Indo-European | 260 | Northern India, Pakistan |

| Arabic | Afro-Asiatic | 223 | Middle East, North Africa |

| Portuguese | Indo-European | 202 | Portugal, Brazil, southern Africa |

| Bengali | Indo-European | 193 | Bangladesh, eastern India |

| Russian | Indo-European | 162 | Russia, Kazakhstan, part of Ukraine, other former Soviet Republics |

| Japanese | Japanese | 122 | Japan |

| Javanese | Austronesian | 84.3 | Indonesia |

Ten Major Languages of the World in the Number of Native Spearkers5

Other important languages and related dialects, whose total number includes both native speakers and second language users, consist of following: Korean (78 million), Wu/Chinese (71 million), Telugu (75 million), Tamil (74 million), Yue/ Chinese (71 million), Marathi (71 million), Vietnamese (68 million) and Turkish (61 million).

Language Spread and Language Loss

Of the top 20 languages of the world, all these languages have their origin in south or east Asia or in Europe. There is not one from the Americas, Oceania or Africa. The absence of a major world language in these regions seems to be precisely where most of the linguistic diversity is concentrated.

- English, French and Spanish are among the world’s most widespread languages due to the imperial history of the home countries from where they originated.

- Two-thirds (66%) of the world’s population speak 12 of the major languages around the globe

- About 3 percent of the world’s population accounts for 96 percent of all the languages spoken today. Of the current living languages in the world, about 2,000 have less than 1,000 native speakers.

- Nearly half of the world’s spoken languages will disappear by the end of this century. Linguistic extinction (language death) will affect some countries and regions more than others.

- In the United States many endangered languages are spoken by Native American groups who reside in reservations. Many languages will be lost in Amazon rain forest, sub-Saharan Africa, Oceania, aboriginal Australia and Southeast Asia.

- English is used as an official language in at least 35 countries, including a number of countries in Africa (Botswana, Kenya, Namibia, Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda among others), Asia (India, Pakistan, Philippines), Pacific Region (Fiji, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, New Zealand), Carib- bean (Puerto Rico, Belize, Guyana, Jamaica), Ireland and Canada.

- English is not by law (de jure) the official language in the United Kingdom, United States and Australia. English does enjoy the status of “national language” in these countries due to its power and prestige in institutions and society.

- English does not have the highest number of native speakers, but it is the world’s most commonly studied language. More people learn English than French, Spanish, Italian, Japanese, German and Chinese combined.6

Dialects of English in the United States

At the time of the American Revolution, three principal dialects of English were spoken. These varieties of English corresponded to differences among the original setters who populated the East Coast.

Northern English

These settlements in this area were established and populated almost entirely by English settlers. Nearly two-thirds of the colonists in New England were Puritans from East Anglia in southwestern England. The region consists of the following states: Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Maine, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Vermont, New York and New Jersey.

Southern English

About half of the speakers came from southeast England. Some of them came from diverse social- class backgrounds, including deported prisoners, indentured servants, political and religious persecuted groups. The following states comprise the region: Virginia, Delaware, North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia.

Midlands English

The settlers of this region included immigrants from diverse backgrounds. Those who settled in Pennsylvania were predominantly Quakers from northern England. Some individuals from Scotland and Ireland also settled in Pennsylvania as well as in New Jersey and Delaware. Immigrants from Germany, Holland and Sweden also migrated to this region and learned their English from local English-speaking settlers. This region is formed by the following areas/states: Upper Ohio Valley, Pennsylvania, Maryland, West Virginia, western areas North and South Carolina.

Dialects of American English have continued to evolve over time and place. Regional differences in pronunciation, vocabulary and grammar do not suggest that a type of linguistic convergence is under- way, resulting in some type of “national dialect” of American English. Even with the homogenizing influences of radio, television, internet, and social media, many distinctive varieties of English can be identified. Robert Delaney (2000) has outlined a dialect map for the United States which features at least 24 distinctive dialects of English. Dialect boundaries are established using diverse criteria: language features (differences in pronunciation, vocabulary and grammar) settlement history, ethnic diversity, educational levels and languages in contact (Spanish/English in the American Southwest). The dialect map does not represent the English varieties spoken in Alaska or Hawaii. However, it does include some urban and social (ethnolinguistic) dialects.

General Northern English, spoken by nearly two-thirds of the country.

New England Varieties

- Eastern New England

- Boston Urban

- Western New England

- Hudson Valley

- New York City

- Bonac (Long Island)

7. Inland Northern English Varieties

- San Francisco Urban

- Upper Midwestern

- Chicago Urban

Midland English Varieties

- North Midland (Pennsylvania)

- Pennsylvania German-English

Western English Varieties

- Rocky Mountain

- Pacific Northwest

- Pacific Southwest

16. Southwest English

17. South Midland Varieties

- Ozark

- Southern Appalachian (Smoky Mountain English)

General Southern English Varieties

Southern

- Virginia Piedmont

- Coastal South

- Gullah (coastal Georgia and South Carolina)

- Gulf Southern

- Louisiana (Cajun French and Cajun English)7

Multilingualism in the United States

Language diversity existed in what is now the United States long before the arrival of the Europeans.

It is estimated that there were between 500 and 1,000 Native American languages spoken around the fifteenth century and that there was widespread language contact and bilingualism among the Indian nations. With the arrival of the Europeans, seven colonial languages established themselves in different regions of the territory:

- English along the Eastern seaboard, Atlantic coast

- Spanish in the South from Florida to California

- French in Louisiana and northern Maine

- German in Pennsylvania

- Dutch in New York (New Amsterdam)

- Swedish in Delaware

- Russian in Alaska

Dutch, Swedish and Russian survived only for a short period, but the other four languages continue to be spoken to the present day. In the 1920’s, six major minority languages were spoken in significant numbers partly to due to massive immigration and territorial histories. The “big six” minority languages of the 1940’s include German, Italian, Polish, Yiddish, Spanish and French. Of the six minority languages, only Spanish and French have shown any gains over time, Spanish because of continued immigration and French because of increased “language consciousness” among individuals from Louisiana and Franco-Americans in the Northeast.

The 2015 Census data for the United States reveals valuable geographic information regarding the top 10 states with the extensive language diversity.

- California: 45 percent of the inhabitants speak a language other than English at home; the major languages include Spanish, Chinese, Korean, Vietnamese, Arabic, Armenian and Tagalog.

- Texas: 35 percent of the residents speak a language other than English at home; Spanish

- is widely used among bilinguals; Chinese, German and Vietnamese are also spoken.

- New Mexico: 34 percent of the state’s population speak another language; most speak Spanish but a fair number speak Navajo and other Native American languages.

- New York: 31 percent of the residents speak a second language; Chinese, Italian, Russian, Spanish and Yiddish; some of these languages can be found within the same city block.

- New Jersey: 31 percent of the state’s residents speak a second language in addition to English; some of the languages spoken include Chinese, Gujarati, Portuguese, Spanish and Italian.

- Nevada: 30 percent of the population is bilingual; Chinese, German and Tagalog are used along with Spanish, the predominant second language of the Southwest.

- Florida: 29 percent of the residents speak a second language, including French (Haitian Creole), German and Italian

- Arizona: 27 percent of the residents claim to be bilingual; most speak Spanish as in New Mexico while others use Native American languages.

- Hawaii: 26 percent of the population claims to be bilingual; Japanese, Chinese, Korean and Tagalog are spoken along with Hawaiian, the state’s second official language.

- Illinois and Massachusetts: 23 percent of their respective populations speak a second language at home; residents of Illinois speak Chinese, German, Spanish and Polish, especially in Chicago; residents of Massachusetts speak Spanish, Haitian Creole, Chinese, Portuguese, Vietnamese and French.8

Top Ten Languages Spoken in U.S. Homes Other Than English

Data from the 2015 American Community Survey ranks the top ten languages spoken in U.S. homes other than English. The data highlight the size of the speaker population, bilingual proficiency (fluency in the home language and English) and degree of English proficiency (LEP, limited English proficiency).

| Rank | Language Spoken at Home | Total | Bilingualism % | Limited English % |

| 1. | Spanish | 64,716,000 | 60.0 | 40.0 |

| 2. | Chinese | 40,046,000 | 59.0 | 41.0 |

| 3. | Tagalog | 3,334.000 | 44.3 | 55.7 |

| 4. | Vietnamese | 1,737,000 | 67.6 | 32.4 |

| 5. | French | 1,266,000 | 79.9 | 20.1 |

| 6. | Arabic | 1,157,000 | 62.8 | 37.2 |

| 7. | Korean | 1,109,000 | 46.8 | 53.2 |

| 8. | German | 933,000 | 85.1 | 14.9 |

| 9. | Russian | 905,000 | 56.0 | 44.0 |

| 10. | French Creole | 863,000 | 58.8 | 41.2 |

Chinese includes Mandarin and Cantonese. French also comprises Haitian and Cajun varieties. German encompasses Pennsylvania Dutch.9

While a record number of persons speak a language at home other than English, a substantial figure within each immigrant group claimed an elevated command of English. Overall, some 60 percent of the speaker groups using a second language at home were also highly fluent in English. Limited fluency in English among young children ranged from a high of 55.7 percent in the Tagalog speaker group to a low of 14.9 percent in the German group which included Pennsylvania Dutch users.10

Most immigrant language groups have tended to follow an intergenerational language shift in the United States. This first generation is basically monolingual, speaking the native language of the group. The second generation is bilingual, speaking both the home language and English. By the third generation, the cultural group is essentially monolingual, speaking only English in most communicative situations.

More recently, some immigrant groups, particularly those with advanced training and degrees in professional fields (technology, health sciences and business), come to the United States with a high degree of fluency in English. At the same time, the variety of English these persons speak is usually marked by the country of origin (India, Philippines, Singapore among others). With globalization “new Englishes” have emerged (Indian English, Filipino English, Nigerian English) which challenge the notion of a Standard English variety (British or American) for use around the world.