13 2.2 THINKING ABOUT POPULATION

2.2.1 The Greeks and Ecumene

No discussion of population is complete without a brief history of the philosophical understanding of population. This discussion starts as it often does, with the ancient Greeks. The Greeks considered that they lived in the best place on Earth. In fact, they believed in the exact center of the habitable part of the Earth. They called the habitable part of the Earth ecumene. To the Greeks, places north of them were too cold, and places to the south were too hot. Placing your own homeland in the center of goodness is common; many groups have done this. The Greeks decided that the environment explained the distribution of people. To an extent, their thinking persists, but only at the most extreme definitions. Many places that the Greeks would have found too cold (Moscow, Stockholm) too hot (Kuwait City, Las Vegas) too wet (Manaus, Singapore) or too dry (Timbuktu, Lima) have very large populations.

2.2.2 Modern Ideas About Population

Thomas Malthus (1766-1834) “Population, when unchecked, increases in a geometrical ratio.” 4

Ester Boserup (1910-1999) “The power of ingenuity would always outmatch that of demand.” 5

Modern discussions of population begin with food. From the time of Thomas Malthus (quoted above), modern humans have acknowledged the rapidly expanding human population and its relationship with the food supply. Malthus himself was a cleric in England who spent much of his time studying political economy. His views were a product not only of his time, but also of his place. In Malthus’ case his time and place were a time of social, political, and economic change.

Karl Marx (1818–1883) took issue with Malthus’ ideas. Marx wrote that population growth alone was not responsible for a population’s inability to feed itself, but that imbalanced social, political, and economic structures created artificial shortages. He also believed that growing populations reinforced the power of capitalists, since large pools of underemployed laborers could more easily be exploited.

The post-World War II period saw a flurry of books warning of the dangers of population growth with books like Fairfield Osborn’s Our Plundered Planet and William Vogt’s Road to Survival. Perhaps most explicit was Paul and Anne Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb.

These books are warnings of the dangers of unchecked population growth. Malthus wrote that populations tend to grow faster than the expansion of food production and that populations will grow until they outstrip their food supplies. This is to say that starvation, war, and disease were all predictions of Malthus and were revived in these Neo-Malthusian publications. Some part of the current conversation of environmentalism regards limiting the growth of the human population, echoing Malthus.

A common theme of these books is that they all attempt to predict the future. One of the advantages we have living centuries or decades after these books is the opportunity to see if these predictions were accurate or not. Ehrlich’s book predicted that by the 1970s, starvation would be widespread because of food shortages and a collapse in food production. That did not happen. In fact, the global disasters predicted in all these books have yet to arrive decades later. What saved us?

Perhaps nothing has saved us. We have just managed to push the reckoning a bit further down the road.

If we have been saved, then the assumptions inherent in the predictions were wrong. What were they?

- Humans would not voluntarily limit their reproduction.

- Farming technology would suddenly stop advancing.

- Food distribution systems would not improve.

- Land would become unusable from overuse.

All of these assumptions have proven to be wrong, at least so far. Only the most negative interpretation of any particular factor in this equation could be accepted.

One the other hand, Ester Boserup, an agricultural economist in the twentieth century, drew nearly the opposite conclusion from her study of human population. Her reason for doing so were manifold. First, she was born one and one -half centuries later, which gave her considerably more data to interpret. Second, she didn’t grow to adulthood in the center of a burgeoning empire. She was a functionary in the early days of the United Nations. Third, she was a trained as an economist, and finally, she was a woman. Each one of these factors was important.

2.2.3 – Let’s Investigate Each One of These Assumptions

In preindustrial societies, children are a workforce and a retirement plan. Families can try to use large numbers of children to improve their economic prospects. Children are literally an economic asset. Birth rates fall when societies industrialize. They fall dramatically when women enter the paid workforce. Children in industrialized societies are generally not working and are not economic assets. The focus in such societies tends to be preparing children through education for a technologically-skilled livelihood. Developed societies tend to care for their elderly population, decreasing the need for a large family. Developed societies also have lower rates of infant mortality, meaning that more children survive to adulthood.

The increasing social power of women factors into this. Women who control their own lives rarely choose to have large numbers of children. Related to this, the invention and distribution of birth control technologies has reduced human numbers in places where it is available.

Farming technology has increased tremendously. More food is now produced on less land than was farmed a century ago. Some of these increases are due to manipulations of the food itself—more productive seeds and pesticides, but some part of this is due to improvements in food processing and distribution. Just think of the advantages that refrigeration, freezing, canning and dehydrating have given us. Add to that the ability to move food tremendous distances at relatively low cost. Somehow, during the time that all these technologies were becoming available, Neo-Malthusians were discounting them.

Some marginal land has become unusable, either through desertification or erosion, but this land was not particularly productive anyway, hence the term marginal. The loss of this land has been more than compensated by improved production.

At this point, it looks like a win for Boserup, but maybe it isn’t. Up to this point we have been mixing our discussions of scale. Malthus was largely writing about the British Isles, and Boserup was really writing about the developed countries of the world. The local realities can be much more complex.

At the global scale there is enough food, and that has been true for decades. In fact, many developed societies produce more food than they can either consume or sell. The local situation is completely different. There are developed countries that have been unable to grow food to feed themselves for over a century. The United Kingdom, Malthus’ home, is one of them. However, no one ever calls the U.K. overpopulated. Why not? Because they can buy food on the world market.

Local-scale famines happen because poorer places cannot produce enough food for themselves and then cannot or will not buy food from other places. Places that are politically marginalized within a country can also experience famines when central governments choose not to mobilize resources toward the disfavored. Politically unstable places may not even have the necessary infrastructure to deliver free food from other parts of the world. This is assuming that food aid is even a good idea (a concept revisited in the agriculture chapter). These sorts of problems persist to this day and they have an impact of population, although often in unpredictable ways, such as triggering large-scale migration or armed conflict.

To recap, at the global level, population has not been limited by food production. However, people do not live at the “global level.” They live locally with whatever circumstances they may have. In many places the realities of food insecurity are paramount.

Although discussions of population tend to start with food, they cannot end with it. People have more needs than their immediate nutrition. They need clothing and shelter as well. They also have desires for a high standard of living- heating, electricity, automobiles and technology. All of these needs and desires require energy and materials. The pressure put on the planet over the last two centuries has less to do with the burgeoning population and more to do with burgeoning expectations of quality of life.

2.2.4 – Scale and the Ecological Fallacy

Numbers can be a little bit misleading. You may read that the “average woman” in the United Sates has 1.86 births and wonder, “What does this tell me about a particular woman?” And the answer is . . . it tells you nothing. Remember that number is an aggregate of the data for the entire country, which means it only works at that scale; it only tells you about the country as a whole. The Ecological Fallacy is the idea that statistics generated at one level of aggregation can be applied at other levels of aggregation.

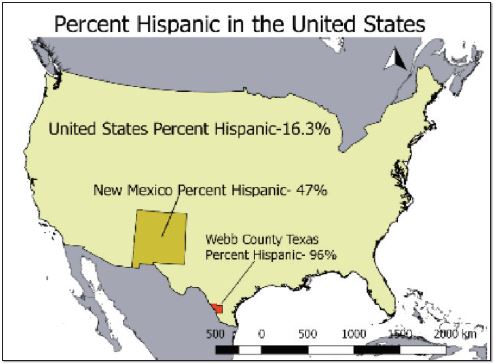

Similarly, one of the biggest problems with maps is that they can make us think that a place is the same (homogenous) within a border. We see a country like the United States, and it has one color for the entire area on the map and we tell ourselves that the U.S. is just one place. And it is. But it’s made of many smaller places. It’s fifty states, and those states combined have 3144 counties (and county-like things). And each one of those things is a level of aggregation. It looks a bit like this (Figure 2.6).

Figure 2.6 | Percent Hispanic aggregated to the County, State, and National level6

Author | David Dorrell

Source | Original Work

License | CC BY-SA 4.0

Webb County only uses the data from one county. New Mexico uses the data for its 33 counties, and the U.S. uses the data for all its counties. Each level of aggregation has its calculated value. They are all different. And they still tell you nothing about an individual person.