86 10.2 AGRICULTURAL PRACTICES

Agriculture is a science, a business, and an art (Figures 10.4 and 10.5). Spatially, agriculture is the world’s most widely distributed industry. It occupies more area than all other industries combined, changing the surface of the Earth more than any other. Farming, with its multiple methods, has significantly transformed the landscape (small or large fields, terraces, polders, livestock grazing), being an important reflection of the two-way relationship between people and their environments. The world’s agricultural societies today are very diverse and complex, with agricultural practices ranging from the most rudimentary, such as using the ox-pulled plow, to the most complex, such as using machines, tractors, satellite navigation, and genetic engineering methods. Customarily, scholars divide agricultural societies into categories such as subsistence, intermediate, and developed, words that express the same ideas as primitive, traditional, and modern, respectively. For the purpose of simplification, farming practices described in this chapter are classified into two categories, subsistence and commercial, with fundamental differences between their practice in developed and developing countries.

Figure 10.4 | Trading Floor at the Chicago Board of Trade

Author | Jeremy Kemp

Source | Wikimedia Commons

License | Public Domain

Figure 10.5 | Tulip Fields in The Netherlands

Author | Alf van Beem

Source | Wikimedia Commons

License | CC 0

10.2.1 Subsistence Agriculture

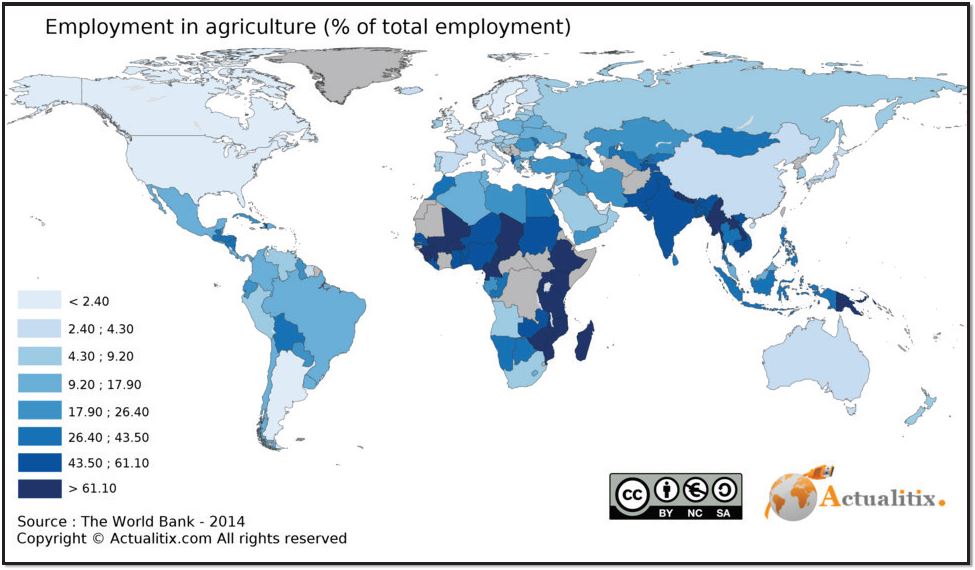

Subsistence agriculture replaced hunting and gathering in many parts of the globe. The term subsistence, when it relates to farming, refers to growing food only to sustain the farmers themselves and their families, consuming most of what they produce, without entering into the cash economy of the country. The farm size is small, 2-5 acres (1-2 hectares), but the agriculture is less mechanized; therefore, the percentage of workers engaged directly in farming is very high, reaching 50 percent or more in some developing countries (Figure 10.6). Climate regions play an important role in determining agricultural regions. Farming activities range from shifting cultivation to pastoralism, both extensive forms that still prevail over large regions, to intensive subsistence.

Figure 10.6 | Employment in Agriculture, 2014

Author | Actualitix

Source | Actualitix.com

License | CC BY NC SA 4.0

Shifting Cultivation

Shifting cultivation, also known as slash-and-burn agriculture, is a form of subsistence agriculture that involves a kind of natural rotation system. Shifting cultivation is a way of life for 150-200 million people, globally distributed in the tropicalareas,especially in the rainforests of South America, Central and West Africa, and Southeast Asia. The practices involve removing dense vegetation, burning the debris, clearing the area, known as swidden, and preparing it for cultivation (Figures 10.7). Shifting cultivation can successfully support only low population densities and, as a result of rapid depletion of soil fertility, the fields are actively cultivated usually for three years. As a result, the infertile land has to be abandoned and another site has to be identified, starting again the process of clearing and planting. The slash-and-burn technique thus requires extensive acreage for new lots, as well as a great deal of human labor, involving at the same time a frequent gender division of labor. The kinds of crops grown can be different from region to region, dominated by tubers, sweet potatoes especially, and grains such as rice and corn. The practice of mixing different seeds in the same swidden in the warm and humid tropics is favorable for harvesting two or even three times per year. Yet, the slash-and-burn practice has some negative impacts on the environment, being seen as ecologically destructive especially for areas with vulnerable and endangered species.

Figure 10.7 | Slash-and-Burn Farming in Thailand

Author | User “mattmangum”

Source | Wikimedia Commons

License | CC BY SA 2.0

Pastoralism

Involving the breeding and herding of animals, pastoralism is another extensive form of subsistence agriculture. It is adapted to cold and/or dry climates of savannas (grasslands), deserts, steppes, high plateaus, and Arctic zones where planting crops is impracticable. Specifically, the practice is characteristic in Africa [north, central (Sahel) and south], the Middle East, central and southwest Asia, the Mediterranean basin, and Scandinavia. The species of animals vary with the region of the world including especially sheep, goats, cattle, reindeer, and camels. Pastoralism is a successful strategy to support a population on less productive land, and adapts well to the environment.

Three categories of pastoralism can be individualized: sedentary, nomadic, and transhumance.

Sedentary pastoralism refers to those farmers who live in their villages and their herd animals in nearby pastures. A number of men usually are hired by the villagers in order to take care of their animals. Equally important is the practice in which the hired men gather the animals (cattle especially) in the morning, feed them during the day in the nearby pasture, and then return them to the village early in the evening. This is the typical pattern for many traditional European pastoralists.

Nomadic pastoralism is a traditional form of subsistence agriculture in which the pastoralists travel with their herds over long distances and with no fixed pattern. This is a continuous movement of groups of herds and people such as the Bedouins of Saudi Arabia, the Bakhtiaris of Iran, the Berbers of North Africa, the Maasai of East Africa, the Zulus of South Africa, the Mongols of Central Asia, and other groups. The settlement landscape of pastoral nomads reflects their need for mobility and flexibility. Usually, they live in a type of tent (known as yurt in Central Asia) and move their herds to any available pasture (Figure 10.8). Although there are approximately 10-15 million nomadic pastoralists in the world, they occupy about 20 percent of Earth’s land area. Today, their life is in decline, the victim of more constricting political borders, competing land uses, selective overgrazing, and government resettlement programs.

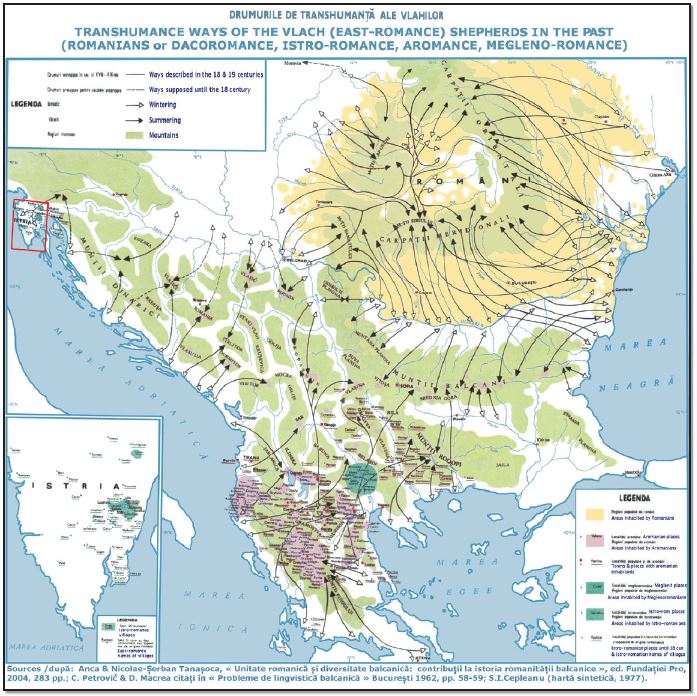

Transhumance is a seasonal vertical movement by herding the livestock (cows, sheep, goats, and horses) to cooler, greener high-country pastures in the summer and then returning them to lowland settings for fall and winter grazing. Herders have a permanent home, typically in the valleys. Generally, the herds travel with a certain number of people necessary to tend them, while the main population stays at the base. This is a traditional practice in the Mediterranean and the Black Sea basins such as southern European countries, the Carpathian Mountains, and the Caucasus countries (Figures 10.9 and 10.10). In addition, near highland zones such as the Atlas Mountains (northwest Africa) and the Anatolian Plateau (Turkey), as well as in Sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East countries, and Central Asia, the pastoralists have to practice another type of transhumance, such as the movement of animals between wet-season and dry-season pasture.

Figure 10.8 | Mongolian Nomads Moving to Autumn Encampment

Author | User “Yaan”

Source | Wikimedia Commons

License | CC BY SA 3.0

Figure 10.9 | Transhumance in the Pyrenees Mountains

Author | User “Clicgauche”

Source | Wikimedia Commons

License | CC BY SA 1.0

Figure 10.10 | Romanian and Vlachs Transhumance in Balkans

Author | User “Julieta39”

Source | Wikimedia Commons

License | CC BY SA 4.0

Intensive Subsistence Agriculture

Intensive subsistence agriculture, characteristic of densely populated regions especially in southern, southeastern, and eastern Asia, involves the effective and efficient use of small parcels of land in order to maximize crop yield per acre. The practice requires intensive human labor, with most of the work being done by hand and/or with animals. The landscape of intensive subsistence agriculture is significantly transformed, including hillside terraces and raised fields, adding the irrigation systems and fertilizers (Figures 10.11 and 10.12). As a result, intensive subsistence agriculture is able to support large rural populations. Rice is the dominant crop in the humid areas of southern, southeastern, and eastern Asia. In the drier areas, other crops are cultivated such as grains (wheat, corn, barley, millet, sorghum, and oats), as well as peanuts, soybeans, tubers, and vegetables. In both situations, the land is intensively used, and the milder climate of those regions allows double cropping (the fields are planted and harvested two times per year).

Figure 10.11 | Rice Terraces, the Philippines

Author | Susan McCouch

Source | Wikimedia Commons

License | CC BY 2.5

Figure 10.12 | Raised fields, Vietnam

Author | Dennis Jarvis

Source | Wikimedia Commons

License | CC BY SA 2.0

In recent decades, as the result of the introduction of higher-yielding grain varieties such as wheat, corn, and rice, known as Green Revolution, tens of millions of subsistence farmers have been lifted above the survival level. The spread of these new varieties throughout the farmlands of South, Southeast, and East Asia, and Mexico greatly improved the supply of food in these areas. Equally important was the use of fertilizers, pesticides, irrigation, and new machines. Today, China and India are self-sufficient in basic foods, while Thailand and Vietnam are two of the top rice exporters in the world. Although hunger and famine still persist in some regions of the world, especially in Africa, many people accept that they would be much worse without using these innovations.

10.2.2 Commercial Agriculture

Commercial agriculture, generally practiced in core countries outside the tropics, is developed primarily to generate products for sale to food processing companies. An exception is plantation farming, a form of commercial agriculture which persists in developing countries side by side with subsistence. Unlike the small subsistence farms (1-2 hectares/2-5 acres), the average of the commercial farm size is over 150 hectares/370 acres (178 ha/193 acres U.S.) and, being mechanized, many of them are family owned and operated. Mechanization also determines the percentage of the labor force in agriculture, with many developed countries being even below two percent of the total employment, such as Israel, the United Kingdom, Germany, the United States, Canada, Norway, Denmark, and Sweden (Figure 10.6). Moreover, as the result of industrialization and urbanization, many developed countries continue to lose significant areas of agricultural land. North America, for example, had 28.3 percent agricultural land out of the total land area in 1961 and 26 percent in 2014. The European Union decreased its agricultural land from 54.7 percent to 43.8 percent for the same period, during which some countries recorded outstanding decreases, such as Ireland from 81.9 to 64.8 percent, the United Kingdom from 81.8 to 71.2 percent, and Denmark from 74.6 to 62.2 percent to mention only a few. In addition to the high level of mechanization, in order to increase their productivity, commercial farmers use scientific advances in research and technology such as the Global Positioning System (autonomous precision seed-planting robot, intelligent systems for animal monitoring, savings in field vegetable-growing through the use of a GPS automatic steering system), and satellite imagery (finding efficient routes for selective harvesting based on remote sensing management).

Climate regions also play an important role in determining agricultural regions. In developed countries, these regions can be individualized as six types of commercial agriculture: mixed crop and livestock, grain farming, dairy farming, livestock ranching, commercial gardening and fruit farming, and Mediterranean agriculture

Mixed Crop and Livestock

Mixed crop and livestock farming extends over much of the eastern United States, central and western Europe, western Russia, Japan, and smaller areas in South America (Brazil and Uruguay) and South Africa. The rich soils, typically involving crop rotation, produce high yields primarily of corn and wheat, adding also soybeans, sugar beets, sunflower, potatoes, fruit orchards, and forage crops for livestock. In practice, there is a wide variation in mixed systems. At a higher level, a region can consist of individual specialized farms (corn, for example) and service systems that together act as a mixed system. Other forms of mixed farming include cultivation of different crops on the same field or several varieties of the same crop with different life cycles, using space more efficiently and spreading risks more uniformly. The same farm may grow cereal crops or orchards, for example, and keep cattle, sheep, pigs, or poultry (Figure 10.13).

Figure 10.13 | Crop-livestock Integration

Sheep grazing under tall-stemmed fruit trees (the Netherlands).

Author | FAO

Source | FAO

License | © FAO. Used with permission.

Grain Farming

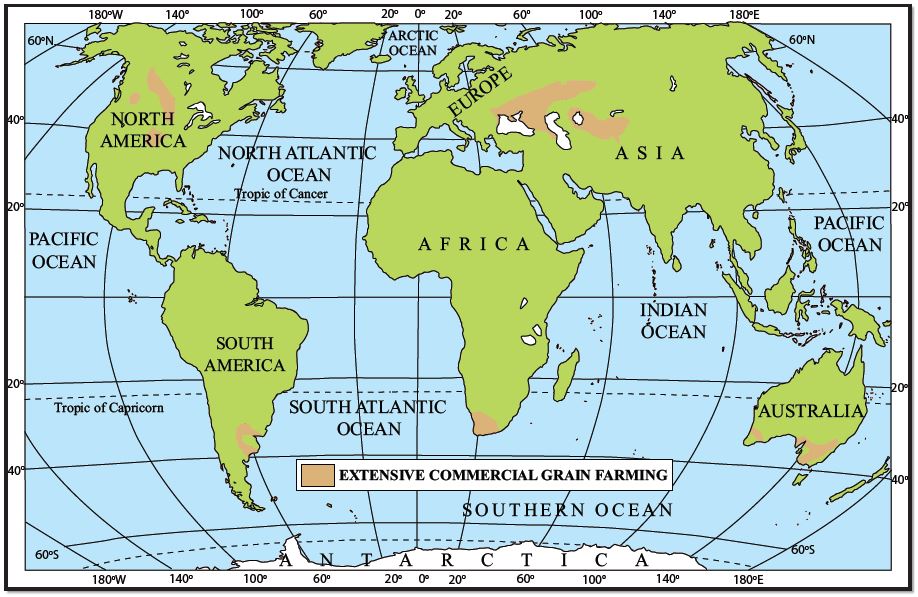

Commercial grain farming is an extensive and mechanized form of agriculture. This is a development in the continental lands of the mid-latitudes (mostly between 30° and 55° North and South latitudes), in regions that are too dry for mixed crop and livestock farming. The major world regions of commercial grain farming are located in Eurasia (from Kiev, in Ukraine, along southern Russia, to Omsk in western Siberia and Kazakhstan) and North America (the Great Plains). In the southern hemisphere, Argentina, in South America, has a large region of commercial grain farming, and Australia has two such areas, one in the southwest and another in the southeast. Commercial grain farming is highly specialized and, generally, one single crop is grown. The most important crop grown is wheat (winter and spring), used to make flour (Figure 10.14). The wheat farms are very large, ranging from 240 to 16,000 hectares (593-40000 acres). The average size of a farm in the U.S. is about 1000 acres (405 hectares). In these areas land is cheap, making it possible for a farmer to own very large holdings.

Figure 10.14 | World Commercial Grain Farming

Author | CIET NCERT

Source | NROER

License | CC BY SA 4.0

Dairy Farming

Dairy farming is a branch of agriculture designed for long-term production of milk, processed either on a farm or at a dairy plant, for sale. It is practiced near large urban areas in both developed and developing countries. The location of this type of farm is dictated by the highly perishable milk. The ring surrounding a city where fresh milk is economically viable, supplied without spoiling, is about a 100-mile radius. In the 1980s and 1990s, robotic milking systems were developed and introduced in some developing countries, principally in the EU (Figure 10.15). There is an important variation in the pattern of dairy production worldwide. Many countries that are large producers consume most of this internally, while others, in particular New Zealand, export a large percentage of their production, some from the organic farms (Figure 10.16).

Figure 10.15 | Rotary Milking Parlor

Author | Gunnar Richter

Source | Wikimedia Commons

License | CC BY SA 3.0

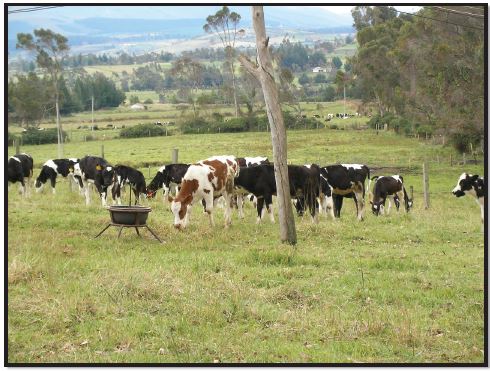

Figure 10.16 | Calves at Organic Dairy Farm

Author | Julia Rubinic

Source | Wikimedia Commons

License | CC BY 2.0

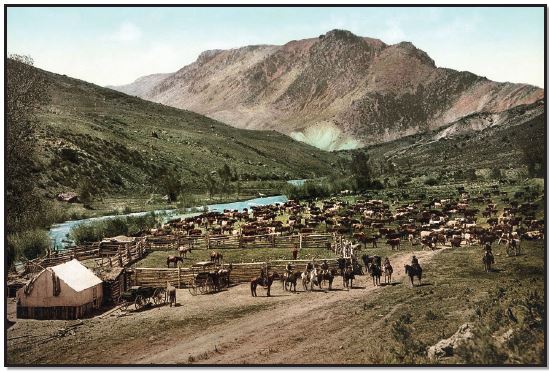

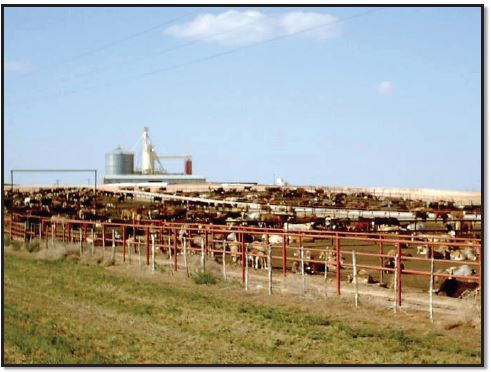

Livestock Ranching

Ranching is the commercial grazing of livestock on large tracts of land. It is an efficient way to raise livestock to provide meat, dairy products, and raw materials for fabrics. Contemporary ranching has become part of the meat-processing industry. Primarily, ranching is practiced on semiarid or arid land where the vegetation is too sparse and the soil too poor to support crops, being a vital part of economies and rural development around the world. In Australia, like in the Americas, ranching is a way of life (Figure 10.17). In the United States, near Greeley, Colorado, there is the world’s largest cattle feedlot, with over 120,000 head, a subsidiary of the food giant ConAgra (Figure 10.18). The largest beef-producing company in the world is the Brazilian multinational corporation JBS-Friboi. Argentina and Uruguay are the world’s top per capita consumers of beef. China is the leading producer of pig meat while the United States leads in the production of chicken and beef.

Figure 10.17 | Ranching

Author | William Henry Jackson

Source | Wikimedia Commons

License | Public Domain

Figure 10.18 | Feedlot in the Texas Panhandle

Author | User “H2O”

Source | Wikimedia Commons

License | CC BY SA 3.0

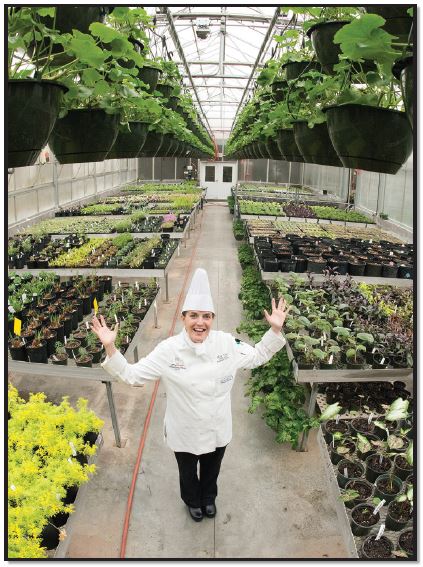

Commercial Gardening and Fruit Farming

A market garden is a relatively small- scale business, growing vegetables, fruits, and flowers (Figure 10.19). The farms are small, from under one acre to a few acres (.5-1.5 hectares). The diversity of crops is sometimes cultivated in greenhouses, dis- tinguishing it from other types of farming. Commercial gardening and fruit farming is quite diverse, requiring more manual labor and gardening techniques. In the United States, commercial gardening and fruit farming is the predominant type of agriculture in the Southeast, the region with a warm and humid climate and a long growing season. In addition to the traditional vegetables and fruits (tomatoes, lettuce, onions, peaches, apples, cherries), a new kind of commercial gardening has developed in the Northeast. This is a non-traditional market garden, growing crops that, although limited, are increasingly demanded by consumers, such as asparagus, mushrooms, peppers, and strawberries. Market gardening has become an alternative business, significantly profitable and sustainable especially with the recent popularity of organic and local food.

Figure 10.19 | Market Farming

A garden with edible plants for use in a culinary school in Lawrenceville, Georgia.

Author | U.S. Department of Agriculture

Source | Wikimedia Commons

License | Public Domain

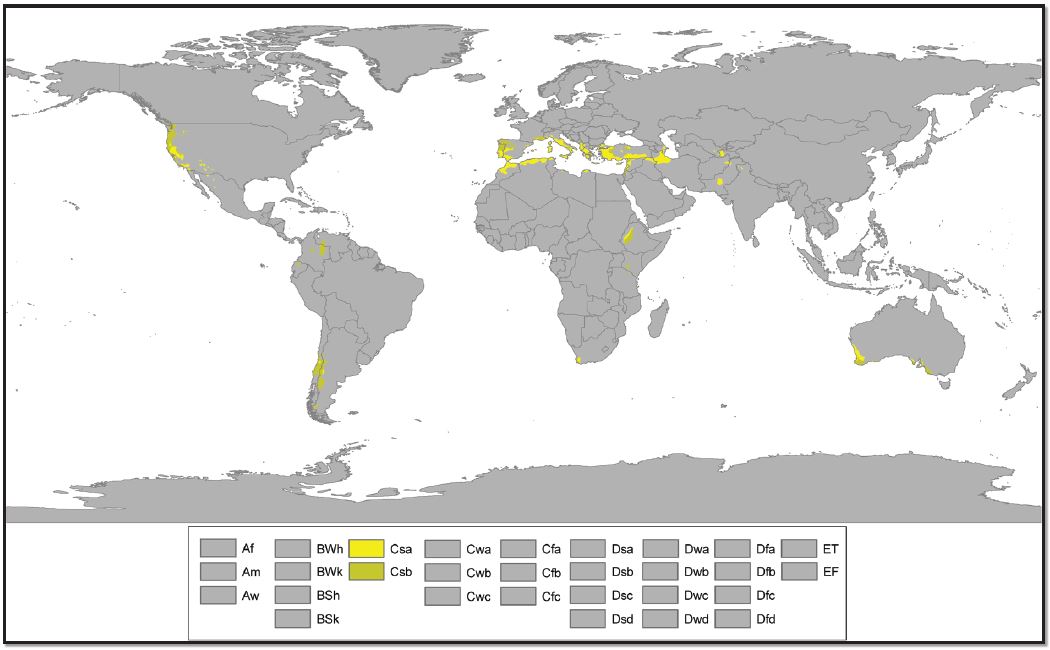

Mediterranean Agriculture

The term ‘Mediterranean agriculture’ applies to the agriculture done in those regions which have a Mediterranean type of climate, hot and dry summers and moist and mild winters. Five major regions in the world have a Mediterranean type of agriculture, such as the lands that border the Mediterranean Sea (South Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East), California, central Chile, South Africa’s Cape, and in parts of southwestern and southern Australia (Figure 10.20). Farming is intensive, highly specialized and varied in the kinds of crops raised. The hilly Mediterranean lands, also known as ‘orchard lands of the world,’ are dominated by citrus fruits (oranges, lemons, and grapefruits), olives (primary for cooking oil), figs, dates, and grapes (primarily for wine), which are mainly for export. These and other commodities flow to distant markets, Mediterranean products tending to be popular and commanding high prices. Yet, the warm and sunny Mediterranean climate also allows a wide range of other food crops, such as cereals (wheat, especially) and vegetables, cultivated especially for domestic consumption.

Figure 10.20 | Mediterranean Regions

Author | User “me ne frego”

Source | Wikimedia Commons

License | CC BY SA 4.0

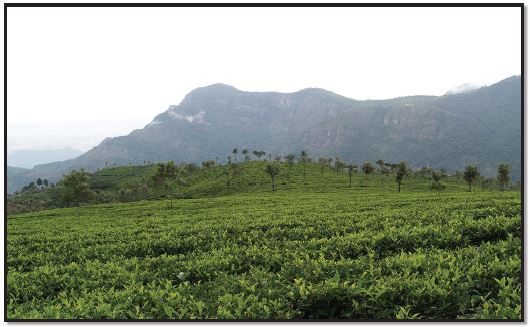

Plantation Farming

Plantations are large landholdings in developing regions designed to produce crops for export. Usually, they specialize in the production of one particular crop for market laid out to produce coffee, cocoa, bananas, or sugar in South and Central America; cocoa, tea, rice, or rubber in West and East Africa; tea in South Asia; rubber in Southeast Asia, and/or other specialized and luxury crops such as palm oil, peanuts, cotton, and tobacco (Figures 10.21 and 10.22). Plantations are located in the tropical and subtropical regions of Asia, Africa, and Latin America and, although they are located in the developing countries, many are owned and operated by European or North American individuals or corporations. Even those taken by governments of the newly independent countries continued to be operated by foreigners in order to receive income from foreign sources. These plantations survived during decolonization, continuing to serve the rich markets of the world.

Unlike coffee, sugar, rice, cotton and other traditional crops, exported from large plantations, other crops can be required by the international market such as flowers and specific fruits and vegetables. These represent the nontraditional agricultural exports, which have become increasingly important in some countries or regions such as Argentina, Colombia, Chile, Mexico, and Central America, to mention a few. One important reason for sustaining nontraditional exports is that they complement the traditional exports, generating foreign exchange and employment. Thus, plantation agriculture, designed to produce crops for export, is critical to the economies of many developing countries.

Figure 10.21| Coffee Plantation

Author | User “Prince Tigereye”

Source | Wikimedia Commons

License | CC BY 2.0

Figure 10.22 | Tea Plantation

Author | User “Joydeep”

Source | Wikimedia Commons

License | CC BY SA 3.0