Learner-Centered Design Theory

Hamzah S. Rajeh

In the last few decades, innovative educators and education scholars have created paradigm shifts in attempts to reform methods of teaching. Their goal was to move beyond didactic instruction where the teacher acts as the conveyor of information and students are merely passive receivers of that information. In its place, active learning has been advocated, which is when students are provided with opportunities to be actively engaged in the construction of meaning. Influenced by the ideas and principles of the user-centered tools developed for computer-based learning, scholars (e.g., Soloway et al., 1994; Quintana et al., 2001) developed the learner-centered design (LCD) approach to teaching and learning in the classroom. LCD Theory is a social constructivist approach that posits that students learn best when they construct meaning in an environment that facilitates their active engagement. As a result, LCD became the basis of a new pedagogical framework developed by Soloway, Guzdian, and Hay (1994), upon which others have continued to add or improve.

Learner-Centered Design

While studying ways to design computers so users are able to learn how to use them more easily, Soloway, Guzdian, and Hay (1994) began focusing on a user-centered approach. Their User-Centered Design Theory was based on the user’s perspective in order to design new computer interfaces and software programs for better usability, in other words, a “user-friendly” approach. The name for the design process was human-computer interaction (HCI). The goal was not just to make computers easier to use, but to help people retain learning and develop more problem-solving skills for the long-term (Soloway, et al., 1994) based on the interface between computers and humans. Students were no longer to be filled with information; they would need to learn how to make sense of the information they received.

HCI used the idea that humans interact with computers differently based on the type of interface used. Wallace (1999) reported that HCI was a process that included both physical and mental actions. The challenge for designers was “to bridge the gaps which exist between the user’s ability to express his goals and intentions through actions and the computers interpretation of those actions – the gulf of execution” (Wallace, 1999, p. 1). User-Centered Design, as used in HCI, was to help users reach the goal of completing a task or creating a product.

Depending on the content and the need to engage various types of learners, multi-modal interfaces (e.g., with visuals, voice, text, etc.) were designed so users could “engage with embodied character agents in a way that cannot be achieved with other interface paradigms” (Smith, 2020, p. 1). Using HCI in design, then, is meant to increase user engagement through such interaction to facilitate more effective learning.

As e-learning became more prevalent, User-Centered Design grew in application. Programs were no longer being designed just for users to learn how to use computers, but other kinds of learning with computer interfacing were being developed. As a result, User-Centered Design learning programs were becoming more common in K-12 classrooms. However, Wallace argues that it is not enough to just shift User-Centered Design into classrooms because she claims programs have not been adequately designed to take into account the needs and characteristics of different types of learners.

The answer to addressing the diverse needs of learners, according to Wallace (1999) and others, is an LCD approach. LCD can be categorized as part of constructivism, which means the idea is not just to transfer content into the minds of learners, but to imprint “a procedure in a student’s cognitive structure by extensive practice” (Wallace, 1999, p. 1). In LCD, learning is viewed as a process where meaning is constructed when students learn to solve problems by finding solutions and organizing concepts into knowledge. The process of learning is the most significant aspect of the approach, because the goal is not just to learn a set of facts or procedures but to facilitate the acquisition of tools to make meaning from a broad range of content. Wallace notes that, “Students can, at least theoretically, engage with computers in processes which offer the possibility of understanding content and constructing knowledge in ways previously unimaginable” (p. 2).

LCD uses some aspects of User-Centered Design of HCI, but it does so in a much more enhanced way. HCI advocates interaction and engagement, but it is limited to learning how to use the computer. Soloway, et al (1996) proposed an LCD framework to better support scaffolding strategies, among other things. The authors also list four components in the LCD to consider–context, tasks, tools, and interface– that are needed for the growth, diversity and motivation of learners (Soloway, et al, 1996).

LCD has been developed further. For example, Lee and Hannafin (2016) present a conceptual design framework for use in LCD. Their idea is “own it, learn it, and share it” (p. 707). Their purpose was to build a better framework on how to apply LCD with actual learning tasks. They claim that their approach is based on the need for students to have ownership of the learning process so that they can achieve learning that is meaningful to them and to learn “autonomously through metacognitive, procedural, conceptual, and strategic scaffolding; and have outcomes that will be aimed at real audiences” (Lee & Hannafin, 2016, p. 708).

Previous Studies

Zaharias and Poulymenakou (2006) recognized that the growing demand for interactive systems for e-learning would require a more human-centered approach to be effective. Consequently, LCD is viewed as more appropriate for general online learning than user-centered design, which is more about learning to use computer programs. Nevertheless, Zaharias and Poulymenakou claim it was still unclear how to implement LCD most effectively. For example, questions about what the best process is and what kind of activities should be used have not been answered sufficiently. So, they conducted a study that implements a new design of a web-based training curriculum. The problems and challenges of applying a learner-centered approach are highlighted. Based on the study, they argue, there is a “need for an effective integration between usability – the ultimate goal for every human-centred design effort – and instructional design concepts, techniques and practices” (p. 87).

Programs that use a learner-centered approach attempt to motivate people to want to learn and know how to learn more effectively (Zaharias & Poulymenakou, 2006). Based on their research and recognizing the need for a well-developed curriculum that was firmly based on learner-centered principles, Zharias and Poulymenakou developed a comprehensive prototype to be used for e-learning. The design included but was not limited to: 1) allowing learners to discover things for themselves, 2) having clearly defined learning objectives, 3) using informative feedback, 4) designing to gain the learners’ attention, 5) employing visual elements to enhance meaning, and 6) facilitating social learning.

In another study, Altay (2014) claimed that LCD is parallel with the “experiential learning model that locates the student learning process in the organization of course activities” (p. 140). Active learning centered on the learner helps students develop the cognitive, affective, and psychomotor domains, a framework presented by Bloom (1956). Altay adds that, “Cognitive domain relates to acquiring knowledge through developing cognitive processes in a hierarchical manner starting from lower order to higher order in the sequence of remembering, understanding, applying, analyzing, evaluating and creating” (p. 140).

Altay (2014) promotes the use of computers in LCD and learning because they offer unique opportunities for individualized interactions and multi-modal presentations of content (e.g., visual, audio, text, interactivity, etc.). These modes stimulate different domains to develop higher order learning skills. To test his claims, Altay conducted a study that used a 15-week curriculum to deliver activities with very visual real-life examples, where students were allowed to be actively engaged with the tasks. Altay described the coursework as case based, where students participated in simulated “enactment in practice” (p. 144). Altay says his study was based on both user-centered design and LCD. From the study, he concluded that it “provides a relation between what is learned; the students’ cognitive and affective learning; with how it is learned, through varying learner-centered methods. Rather than passive learning, knowledge is constructed and transformed through the interaction of the designer/student within the ‘learning environment’ shaping one’s own professional identity and role respectfully” (p. 153).

Model of LCD Theory

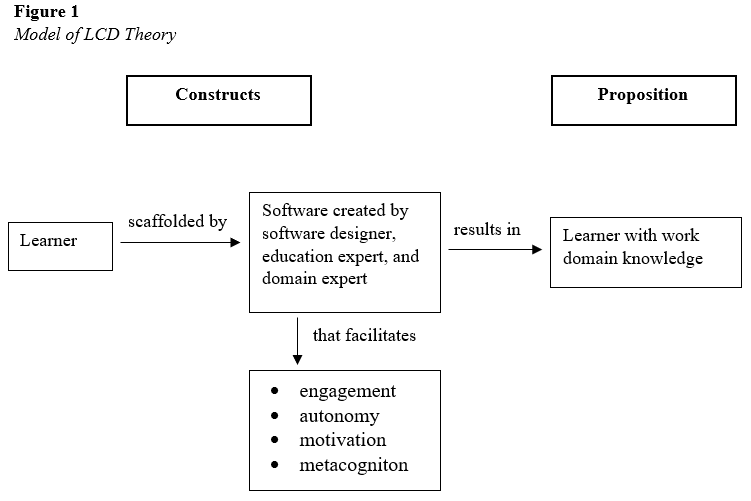

When learners start using technology in class to learn, they need to be supported and engaged in using scaffolding, which not only comes from the design of the learning program but how it is applied with the teacher’s support. Figure 1 illustrates the process of LCD theory in with constructs and the propositions.

Constructs

Originally, User-Centered Design was to show how learners build their knowledge through active engagement in the professional work culture and develop an understanding of the common practices, languages, tools, and values of a professional culture (Soloway, et al., 1996). LCD theory includes constructs such as engagement, motivation, and metacognition that support enhanced learning achievement with the support of well-designed, applied technology. When used as part of a well-designed instructional framework, it supports learners to achieve their learning goals.

Proposition

LCD proposes that when the principles are applied to learning environments, learner autonomy and engagement are supported through scaffolding and learners are better able to achieve e-learning objectives.

Using the Model

The research studies presented above tested specific applications that can be used to guide educators in developing their own LCD. Whatever curriculum is chosen, it is clear that a learner-centered design requires a multi-pronged approach with active learning that taps into various types of learning and domains. Students need to be active in creating meaning from the tasks they complete, and a component of reflecting on what they have learned is important from a metacognitive perspective. Most important, teachers need to be thoughtful about including the various components of LCD as identified in recent research.

LCD in research has not been studied deeply with students in the field. There are a limited number of studies that investigate the effectiveness of LCD on students’ achievement, and there are few systematic reviews; these can be topics of future research. In addition, researchers might investigate more specifically the roles of teachers and designers in designing educational software. For instance, teachers must emphasize their students’ needs and curricular objectives for analysis and design by designers. Designers need to be aware of learning objectives, educational frameworks, or thinking levels (e.g., remember, understand, apply, analyze, evaluate, and create). So, researchers, teachers, and designers need to collaborate to design supportive software for students to achieve their goals; whether and how this happens should be the subject of future investigation.

Conclusion

The last few decades have brought forward a shift in teaching paradigms. Learner-centered methodologies have become more widely accepted as effective ways to guide student learning. However, it has taken a while for scholars and educators to develop models for applying the principles of LCD into student learning environments. This chapter presented some of the developments in this area that can help teachers and researchers apply LCD principles and concepts to help learners achieve their goals.

References

Altay, B. (2014). User-centered design through learner-centered instruction. Teaching in Higher Education, 19(2), 138–155.

Bloom, B.S. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Longman.

Lee, E. & Hannafin, M. (2016) A design framework for enhancing engagement in student-centered learning: Own it, learn it, and share it. Educational Technology Research & Development, 64(4), 707–734.

Smith, M. (Sept. 05, 2020). Human computer interaction. iMedPubJournals. http://www.imedpubjournal.org/blog/humancomputer-interaction-hci-7803.html

Soloway, E., Guzdial, M., & Hay, K.E. (1994). Learner-centered design: The challenge for human computer interaction in the 21st century. Interactions, 1, 36-48.

Soloway, E., Jackson, S., Klein, J., Quintana, C., Reed, J., Spitulnik, J., Stratford, S., Studer, S., Jul, S. Eng, J., & Scala, N. (1996). Learning theory in practice: Case studies of learner-centered design. https://dl.acm.org/doi/fullHtml/10.1145/238386.238476

Quintana, C., Soloway, E., & Norris, C. (2001, August). Learner-centered design: Seveloping software that scaffolds learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies (pp. 0499-0499). IEEE Computer Society.

Wallace, R. (1999, January). Users as learners, learners as users. Michigan State University. What’s the difference? https://msu.edu/~mccrory/_pubs/HCIC_LCDboaster.htm

Zaharias, P., & Poulymenakou, A. (2006). Implementing learner‐centred design: The interplay between usability and instructional design practices. Interactive Technology and Smart Education, 3(2), 87–100.