Language Task Engagement (Theory)

Joy Egbert

Task engagement can be described generally as when students “expend focused energy and attention, and they are emotionally involved” in the task at hand (Philip & Duchesne, 2016, p. 52). Research provides evidence that task engagement is positively correlated with learning and achievement across disciplines such as driving (Lin, et al, 2020), engagement across task transitions at work (Newton, et al, 2019), and language learning (Nakamura, et al, 2020). The current interest in task engagement was initiated in the field of education psychology, although constructs and theories of task engagement include elements of behavioral, cognitive, sociocultural, constructionist, and even critical theories.

There is not yet enough evidence to support a Theory of task engagement, particularly in language education; this is in part because educators, researchers, and theorists have often looked only at parts of the construct. Brought together, however, the evidence base for crucial task engagement elements and relationships among them is fairly strong (see, for example, Christenson, Reschly, & Wylie, 2012). As Oga-Baldwin (2019) notes, engagement is “perhaps one of the most crucial steps in predicting how students succeed at languages in formal education settings” (p.104). In an attempt to offer a cohesive understanding of language task engagement, Egbert, et al (2019) proposed a model of language task engagement that included task elements, engagement indicators and facilitators, and possible outcomes. This chapter proposes additions to the original model; research using this model can help develop a true Theory of language task engagement.

Previous Research

Language task engagement does not address what students learn but rather how they might be engaged in learning it and what the outcomes of being engaged might be. For example, Ahn (2016) used a qualitative methodological framework grounded in the cognitive, affective, and social dimensions of engagement to study 83 language play episodes. Ahn found that the use of language “play” helped students understand the contexts of language use and how language could be used to create meaning and meaningful interaction.

Studies from other disciplines also inform language task engagement. For example, in a study focused on situational and individual interest in science (both seen as engagement facilitators), Ainley (2012) used a dynamic systems perspective to investigate what triggers interest and what its relationship to task engagement might be. Ainley’s results showed that individual interest can significantly predict students’ on-task interest and that students with higher initial interest persist longer in tasks that addresses that interest. Ainley also pointed out that motivation and engagement are two separate constructs, and that students’ cultures can influence their engagement.

Many recent studies explore the influence of technology uses on student task engagement. For example, Hamari, et al (2016) explored task engagement and learning in game-based learning environments. Using the concept of Flow (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990) to frame the notion of task engagement, the researchers engaged 173 students in challenging games. They found that, as Flow theory suggests, challenge was a strong predictor of learning outcomes. They also presented evidence that educational video games can engage students and that such engagement positively affects learning outcomes.

Overall, there is a large body of literature that addresses task engagement, including language task engagement specifically, in some way. A model may help teachers and researchers make sense of this diverse and unwieldy amount of evidence by providing a way to visualize the essential components of task engagement.

The Model

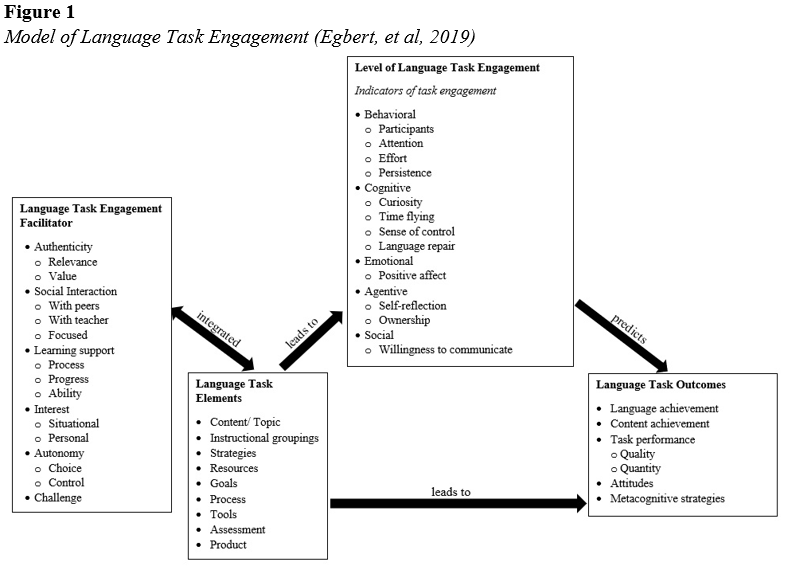

Figure 1 presents Egbert, et al’s (2019) original model. This model was first proposed as a way to visualize the elements of task engagement proposed in the literature.

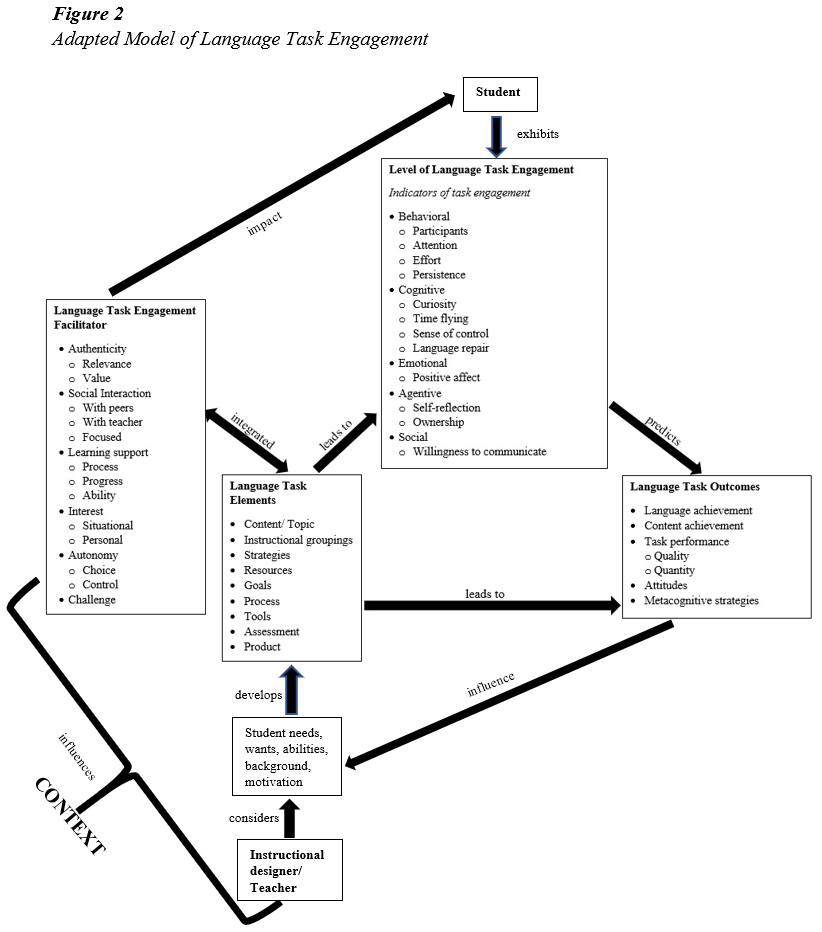

Figure 2 presents an adapted version of the model that adds the crucial components of agents and context. As studies progress, more will be known about each element and the model can be further refined; however, a complete and detailed model would be very complex and thereby less likely to be effective for classroom use.

Concepts, Constructs, and Proposition

The model in Figure 2 proposes that tasks designed with engagement facilitators that are based on student needs, wants, abilities, backgrounds, and motivation(s) can lead to student task engagement. Task engagement can be measured by any the indicators, and the level of engagement then predicts both positive and negative outcomes.

Within each main construct of the model (i.e., facilitators, indicators), additional constructs and the concepts that comprise them provide additional details that can be used and studied.

Using the Model

The model of language task engagement presented in Figure 2 has many components, but not all of them must be addressed in each learning context to engage students in learning. Teachers and researchers with an understanding of a specific learning context can choose to integrate and investigate facilitators that make sense in that environment.

For Teaching

To start, teachers who create tasks for their classrooms should consider themselves as instructional task designers. Their first step to engaging their students in tasks, then, is to learn about their students’ needs, wants, and so on; there are many resources around the Web (see, for example, www.pinterest.com) for help with gathering this information. Then, teachers can consider each of the language task elements and reflect on which facilitators might make the task more engaging to their specific students. For example, they can think about how resources can provide students with sufficient effective learning support and what might make the resources more interesting for students to use. Teachers can also contemplate how autonomy can be integrated into the task goals or product. Overall, the model offers a list of opportunities and possibilities for task design and instruction, but ultimately teachers must figure out how to use it most effectively in their contexts.

For Research

Studies have addressed both single relationships in the model (e.g., the effect of peer interaction on emotional engagement) and the connections among multiple elements (e.g., how the indicators overlap), but much more has yet to be discovered. Some of the topics that researchers can address include the interaction of the model’s variables (as Philip & Duchesne, 2016, suggest), the measurement of multiple variables across different student populations and languages, how student task engagement might affect the engagement of peers, and the path of the model in general. In addition, while a number of language task engagement instruments and measures have been developed, there is no consistency across them. Researchers can work toward a more unified construct and measures of it, and then validate them across cultures and disciplines.

Conclusion

Even the adapted model in Figure 2 does not address all of the issues with, evidence for, and theories of task engagement. Perhaps it does not need to, but that is yet unclear. Truly, in spite of the large body of published work, an understanding of language task engagement, and task engagement across cultures, disciplines, and students, is just beginning.

References

Ahn, S. (2016). Exploring language awareness through students’ engagement in language play. Language Awareness, 25(1-2), 40-54.

Ainley, M. (2012). Students interest and engagement in classroom activities. In S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 283-302). Springer.

Christenson, S. L., Reschly, A. L., & Wylie, C. (Eds.). (2012). Handbook of research on student engagement. Springer.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal performance. Harper Collins Publishers, Inc.

Egbert, J., Shahrokni, S., Zhang, X., Abobaker, R., Bantawtook, P., He, H., Bekar, M., Roe, M.F., & Huh, K. (2019, November 20). Creating a model of language task engagement: Process and outcomes [presentation]. Research Conversation, Washington State University, Pullman.

Hamari, J., Shernoff, D. J., Rowe, E., Coller, B., Asbell-Clarke, J., & Edwards, T. (2016). Challenging games help students learn: An empirical study on engagement, flow and immersion in game-based learning. Computers in Human Behavior, 54, 170-179.

Lin, R., Xu, Y., Zhang, W. (2020). The role of attentional networks in secondary task engagement in the context of partially automated driving. In N. Stanton (Ed.), Advances in Human Aspects of Transportation, 1212. Springer.

Nakamura, S., Phung, L., & Reinders, H. (2020). The effect of learner choice on L2 task engagement. Studies in Second Language Acquisition. First View: cambridge.org/core/journals/studies-in-second-language-acquisition/article/effect-of-learner-choice-on-l2-task-engagement/63A0807738A0A9CCD1A5ECD05237BBED

Newton, D., LePine, J., Kim J, Wellman, N. & Bush, N. (2019). Taking engagement to task: The nature and functioning of task engagement across transitions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(1), 1-18.

Oga-Baldwin, W. (2019). Acting, thinking, feeling, making, collaborating: The engagement process in foreign language learning. System, 86, 102-128.

Philip, J., & Duchesne, S., (2016). Exploring engagement in tasks in the language classroom. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 36, pp. 50-72.