Care Theory

Robin Mays

Initially, studies that examined how relationships of care and connection make moral judgments and decisions difficult relied upon gendered distinctions among participants (Gilligan, 1982). For example, whereas a boy would make a “just” decision, a girl seemed “unsure” (p. 204). Later, however, Gilligan and Wiggins (1987) concluded there is “no neutral position from which to comment on sex differences” (p. 279), relying instead on the potentially inescapable perspective of one’s gender. Exploring individual caring relationships that lead to understanding how and why moral decisions are made, regardless of gender, became the foundation of care theory.

In the last thirty-five years, Noddings (2002) fostered and developed care theory, focusing primarily on the value of relationships. She notes that “all teachers are moral educators” with a responsibility to produce “better adults” (Noddings, 2015, p. 235) and “education is relation” (Noddings, 2016, p. 67); therefore, individual receptive actions between carer and cared-for serve as the very foundation for care theory. These relationships, demonstrated through modeling, dialogue, practice, and confirmation, are the means for teachers and leaders to encourage a moral life, however it is defined, which is then evidenced in decision-making among students. For a comprehensive look at Noddings’ work and the complexities of care in education, see Owens and Ennis (2005).

Previous Studies

Previous studies that apply care theory fall into two distinct categories: 1) studies that attempt to utilize care theory in the classroom toward measured outcomes, and 2) studies that apply care theory to leadership practices in education more generally. One commonality to all the studies is that they recognize the need for a relationship between the carer and the cared-for. Placing care theory into these two categories helps answer the question, “How shall we live well together?” (Strike, 2007, p. 19) through moral decision-making and provides input into how teachers and leaders can create caring relationships.

In education leadership, studies have emerged to explore the impact of care theory in making ethical decisions (Bass, 2009; Kropiewnicki & Shapiro, 2001); many of these studies employ a qualitative methodological framework, using interviews and case studies of women in general and women of color in particular. These studies provide evidence that, within their spheres of influence, women are responding to injustices even when their personal interest is at risk (Bass, 2009). Their demonstration of care is seen by their ability to identify with the situation, take responsibility, and accept consequences that may occur (Bass, 2009). Kropiewnicki and Shapiro (2001) demonstrate care theory at work through case studies in which their participants (female principals) respond not only to the problem at hand, but also to the circumstances that surround the problem. As an extension of care toward others, the principals appear to care about the situation, including ideas and causes, as they relate to consequences of the problem.

In the classroom, care theory has also been identified as a pathway to potentially improve student outcomes across grades and cultures (Newcomer, 2018; Noddings, 2012; Meyers, 2009). For example, Noddings (2012) argues that an important task for teachers is to “connect the moral worlds of school and public life” (p. 779). Several studies demonstrate how this is possible in a contemporary classroom, including in higher education. Specifically, Meyers (2009) presents literature that demonstrates that students “identify rapport as an important and discrete dimension of college teaching” (p. 208). Caring can be implemented at any level by building a relationship between the faculty member and the student through verbal immediacy (Meyers, 2009, p. 207). Newcomer (2018) provides evidence of the benefit of a caring relationship specifically between Latinx students and teachers, noting that feeling like a family can make a positive difference in a student’s life.

Several researchers describe how the inclusion of moral development in the classroom happens in multiple ways—outside of the traditional conversation or explicit demonstration of care (Hilder, 2005; Shevalier & McKenzie, 2012; Zembylas, 2017). For example, texts that model ethical decision makers through storytelling can be influential at any grade level to illustrate care (Hilder, 2005). In higher education, disruptive teaching relies on caring relationships, too. For example, when it is considered alongside critical care theory and pushes students to ask and respond to uncomfortable questions, it relies on the establishment of relationships of care to provoke questions of equity and power relationships, and it challenges the increased “emotional burden of responsibility allocated to marginalized groups who have to deal with the choices made by privileged groups” (Zembylas, 2017, p. 10). In addition, culturally responsive teaching relies on caring, particularly when “teachers view dialog and attention as integral parts of the teaching and learning process” (Shevalier & McKenzie, 2012, p. 1995). These studies demonstrate that once a foundation of a caring relationship is established, modeling, dialogue, practice, and confirmation make the nuances of future student moral decision making more distinct and explicit.

Model of Care Theory

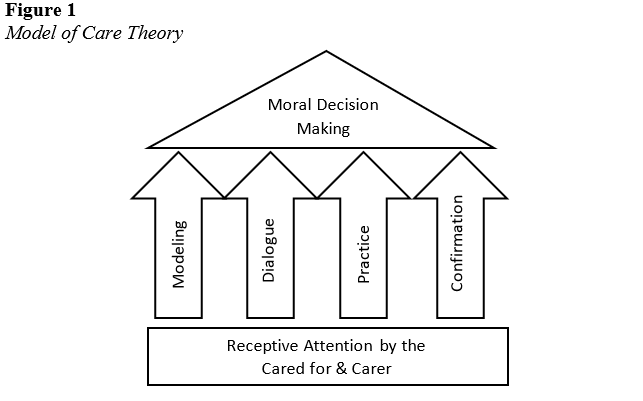

The basis of the model presented in Figure 1 is a relationship defined by receptive attention between the cared-for and carer. The aim is not to “produce people” (Noddings, 2002, p.9), but rather to contribute to understanding how moral decisions are made.

Concepts

The four main concepts in care theory, strengthened by the foundation of receptive care, are modeling, dialogue, practice, and confirmation (Noddings, 2002). Together these concepts strengthen the ability to understand how moral decisions are made; however, they can be taken singularly and still achieve that goal. Teachers and leaders may already engage in these behaviors, as described in Table 1.

Table 1

Behaviors Associated with Concepts

|

Concepts |

Behaviors |

|

Modeling |

Take opportunities to demonstrate the ability to care, but do not lose attention for the cared-for. |

|

Dialogue |

Open conversations during which the participants do not know how it will end; both speak and both listen receptively. |

|

Practice |

Engage regularly in care-giving activities to develop the ability to care |

|

Confirmation |

Assign the best possible motive to one’s actions; success depends on a relationship between the cared-for and the carer. |

Proposition

The goal of achieving better understanding of moral decision-making first begins with building a relationship between cared-for and carer. Once the relationship is established, it is possible to engage in behaviors, such as modeling, dialogue, practice, and confirmation, which will lead to the better understanding of one’s moral decision-making. Just as the definition of moral decision-making is contextual and varies, so too are the decisions themselves. This model presents an opportunity for greater understanding of a decision, not a path to a specific decision.

Using the Model

For Teaching

As an educator approaches a relationship with a student, the model demonstrates a way to critically consider teacher behaviors, approaches, and even course design. The questions listed below are ways for educators to critique themselves, the conduct of their classrooms, and/or their leadership styles to determine how care is being utilized and whether a student could benefit from the explicit presence of care.

-

How can my relationships with my students incorporate all four of the concepts?

Not all four concepts are simultaneously needed to guide the moral decision- making process; however, by incorporating each aspect, care can be improved.

-

Are the people around me (i.e., students, staff, fellow faculty) aware that my decisions and designs are coming from a place of care?

It is imperative that the care is recognized by the carer and cared-for for the model to be effective.

-

There is no distinction between obligatory care and natural care (Noddings, 2016), yet they are both necessary for the care to be reciprocal. Because of this, how can I use both approaches to support my teaching and/or leadership initiatives?

For Research

When approaching education research either in leadership or instruction, the model represents how care can be developed and demonstrates how the concepts build an understanding of how moral decisions are made. The questions and statements listed below are examples of approaches one can take to design a study and also to critique one’s own conclusions about the role of care and relationships:

-

Is receptive knowledge of care, which is needed to establish a caring relationship, explicit in your design? To your participants? Throughout the research phase? When analyzing your results? To your reader as you share new knowledge?

-

Because care is a relational and receptive experience, have you established a caring relationship, potentially through clear lines of communication or transparent processes? How do you plan to demonstrate and measure this in your study?

-

When analyzing your outcomes, how can care theory account for patterns of behavior among the faculty, students, and other personnel? Was this outcome expected? How can it be strengthened and potentially replicated?

Conclusion

Care theory, built on the foundation of a relationship between the carer and cared-for, demonstrates that, with the explicit behaviors of modeling, dialogue, practice, and confirmation, teachers and leaders can encourage moral decision-making. Although these decisions are not pre-scripted and there is not a clear definition of what a moral decision is, the moral decision is more easily examined and understood when these behaviors are practiced. As an approach to learning and leading, the potential is great with its use to improve our understanding of decision-making within context rather than as a prescriptive outcome (Noddings, 2002). This model is designed to help all educators better understand the foundation of and behaviors within care theory with the aim of recognizing the complexities of moral decision-making.

References

Bass, L. (2009). Fostering an ethic of care in leadership: A conversation with five African American women. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 11(5), 619-632.

Bass, L. (2012). When care trumps justice: The operationalization of Black feminist caring in educational leadership. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 25(1), 73-87.

Engster, D. (2005, Summer). Rethinking care theory: The practice of caring and the obligation to care. Hypatia, 20(3), 50-74.

Gilligan, C. (1982). New maps of development: New visions of maturity. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 52(2), 199-212.

Gilligan, C., & Wiggins, G. (1987). The origins of morality in early childhood relationships. In J. Kagan, & S. Lamb (Eds.). The emergence of morality in young children (pp. 277-305). University of Chicago Press.

Hilder, M. B. (2005). Teaching literature as an ethic of care. Teaching Education, 16(1), 41-50.

Kropiewnicki, M. I., & Shapiro, J. P. (2001). Female leadership and the ethic of care: Three case studies. Annual Meeting of the American Education Research Association. Seattle.

Meyers, S. A. (2009). Do your students care whether you care about them? College Teaching, 57(4), 205-210.

Newcomer, S. (2018). Investigating the power of authentically caring student-teacher relationships for Latinx students. Journal of Latinos and Education, 17(2), 179-193.

Noddings, N. (2002). Educating moral people: A caring alternative to character education. Teachers College Press.

Noddings, N. (2012, December). The caring relation in teaching. Oxford Review of Education, 38(6), 771-781.

Noddings, N. (2015, April). A richer, broader view of education. Sociology, 52, 232-236.

Owens, L. M., & Ennis, C. D. (2005). The ethic of care in teaching: An overview of supportive literature. Quest, 57, 392-425.

Shevalier, R., & McKenzie, B. A. (2012). Culturally responsive teaching as an ethics-and care-based approach to urban education. Urban Education, 47(6), 1086-1105.

Zembylas, M. (2017). Practicing an ethic of discomfort as an ethic of care in higher education teaching. Critical Studies in Teaching & Learning, 5(1), 1-17.