Attribution Theory

Yustinus Calvin Gai Mali

According to Dörnyei (2001), attributions are “explanations people offer about why they were successful or, more importantly, why they failed in the past” (p. 118). Attributional studies began in the field of social psychology in the 1950s, and Fritz Heider became the “father” of attributions’ theory and research (Dasborough & Harvey, 2016, n. p.). Besides Heider, Bernard Weiner is also well-known for his significant contributions to the development of attribution theory (see, for example, Weiner, 1972, 1976, 1985), which can be categorized as a cognitivist theory (David, 2019).

Previous Studies

Attribution studies have three commonalities. First, in research in education, attribution has been widely cited as one of the key factors in students’ learning motivation and achievement (see, e.g., Banks & Woolfson, 2008; Weiner, 1972). Similarly, Hsieh and Schallert (2008) suggest that how students attribute their past failures may influence how they approach future performances. In this situation, students will have more motivation to enhance their practices when they perceive their learning failure within themselves rather than within external factors that they cannot control (Ellis, 2015). For example, if students believe that they can succeed by making a greater effort, they are more likely to keep trying than if they believe that their teachers do not like them.

Second, previous studies (e.g., Chedzoy & Burden, 2009; Farid & Akhter, 2017; Mali, 2015; Williams, Burden, Poulet, & Maun, 2004) often classified attributions for success and failure and summarized the results in tables with frequency numbers and percentages. For instance, Williams et al. (2004) surveyed 285 11 to 16 year-old students’ attributions in learning foreign languages in five secondary schools in the United Kingdom. The study found that effort became the most widely cited attribution for the students’ learning successes or failures. More specifically, male students appeared to attribute their success to their effort more than female students did, while younger female students most commonly attributed their failure to ability. More recently, Mali (2015) adapted the open-ended questionnaire used in Williams et al.’s study to explore attributions of students’ English speaking achievement, such as their being able to perform a monologue or ask and answer questions using English. The study concluded that positive relationships between the students and teacher as well as among the students themselves were the primary attribution for English-speaking achievement. Based on these findings, Mali reminded language teachers to always maintain good rapport with their students, create positive relationships among the students themselves, and explain why their students need to perform a specific classroom activity.

A third commonality in attribution studies is the use of a questionnaire to explore attributions. In attribution studies, questionnaires often employ closed-ended questions like those in Figure 1. (For the original format of the close-ended questions, see the article). For another type of closed-ended questions, see Peacock’s (2010) study.

Figure 1

Example Question from an Attribution Questionnaire

Perceptions of English Language Learning. Think about your past experiences in the 1st semester English class. Try to remember a time in which you did particularly WELL/ POORLY on an activity in the class. The activity you are thinking of might be listed below. If so, circle the activity. If the activity is not listed below, circle the “other. . .” and describe the activity in the space provided. Be sure to choose only ONE activity.

-

Reading texts using appropriate strategies

-

Answering comprehension questions

-

Learning vocabulary

-

Understanding grammar

-

Translating texts and passages from English

-

Other writing activities…………………….

(Mori, et al, 2010, p. 26-27).

In addition, respondents may also be asked to answer open-ended questions based on their previous knowledge or real-life experiences. Open-ended questions (adapted from Williams et al., 2004) may include the following:

-

When I do well in English, the main reasons are:

-

When I don’t do well in English, the main reasons are:

In the blanks, respondents can write the answers without following a fixed set of options as they do with close-ended questions. For other similar types of open-ended questions, see other studies such as Mali (2015), Tse (2000), and Yilmaz (2012).

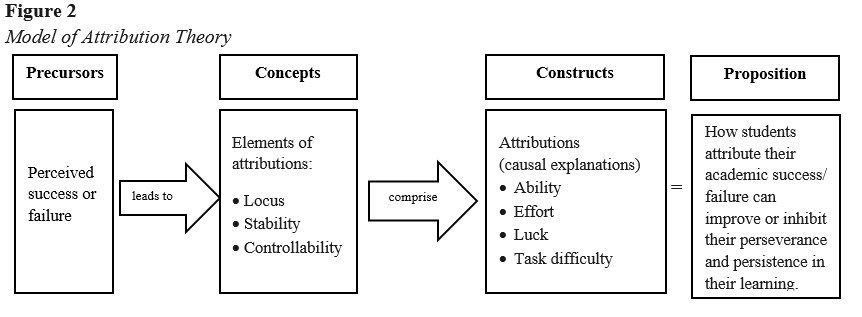

Model of Attribution Theory

Figure 2 presents a model of attribution theory. The model consists of precursors, or what comes before an attribution, and a process with concepts, constructs, and the theory’s proposition.

Precursors

The attribution theory model starts with the precursors, where people remember their success or failure in the past and begin to explain to themselves why they could be successful or fail in their language learning.

Concepts

After the students perceive reasons for their successes or failures, they then ascribe the reasons in three main dimensions: locus, stability, and control (see Weiner, 1976, for more details). Weiner explains that locus is whether people perceive a particular cause as being internal or external. Stability is whether a specific cause is something stable (fixed) or unstable (can change). Meanwhile, control is about how much control the student has over a particular reason. Vispoel and Austin (1995) combined the three main dimensions and four causal explanations of attribution into a table to create a classification scheme for causal attributions; see Table 1 for an example of how these concepts work together. Attribution studies in different settings (e.g., Farid & Iqbal, 2012; Farid & Akhter, 2017; Mori et al., 2010; Gobel, Thang, Sidhu, Oon, & Chan, 2013; Rasekh, Zabihi, & Rezazadeh, 2012; Thang, Gobel, Mohd. Nor, & Suppiah, 2011) often discuss this scheme in their literature review or use some components of the scheme to develop research instruments.

Table 1

Dimensional Classification Scheme for Causal Attributions

| Dimensions | |||

| Attributions | Locus | Stability | Controllability |

| Ability | Internal | Stable | Uncontrollable |

| Effort | Internal | Unstable | Controllable |

| Strategy | Internal | Unstable | Controllable |

| Interest | Internal | Unstable | Controllable |

| Task Difficulty | External | Unstable | Uncontrollable |

| Luck | External | Unstable | Uncontrollable |

| Family influence | External | Stable | Uncontrollable |

| Teacher influence | External | Stable | Uncontrollable |

(Vispoel & Austin, 1995, p. 382)

Constructs

Four possible causal explanations (e.g., ability, effort, luck, or task difficulty) comprise the three main dimensions of locus, stability, and control to which a particular cause is attributed. For instance, Weiner (1985) quoted a story of a Japanese warrior, Miyomota Musashi, who attributed his previous victories to natural ability. Weiner also instanced a football coach, Ray Malavasi, who related nine consecutive losses of his team to his players who were not doing their best. More recently, Mori et al. (2010) explained that effort refers to “a cause that is internal, unstable, controllable, while an ability is something internal, beyond personal control, and that endures over time” (p. 7). The literature (e.g., Dörnyei, 2001; Ellis, 2015; Weiner, 1976, 1985) suggests that when students refer their failures to an internal, unstable, and controllable attribution, such as lack of effort, they will enhance their motivation to do better and work harder.

Proposition

In the end, attribution theory proposes that students might enhance their perseverance and persistence to achieve learning goals more successfully when they attribute their success or failure to internal, unstable, and controllable causes, such as effort (Dörnyei, 2001; Mori et al., 2010).

Using the Model

There are many possible ways to use the model for teaching and research purposes. For teaching purposes, for example, teachers can ask their students to think about a failure they experienced in a language class. Next, the students can write a self-reflective essay on why they think they failed and what they can learn from the failure to enhance future performance. Teachers can use the model to figure out common attributions in the students’ essay and work with the student to figure out ways to perceive their learning based on internal, controllable factors. Then, like Demetriou (2011) suggests, teachers can collaborate with their students to plan future action based on the common attributions revealed in the essay.

For research purposes, studies can test the proposition of the model; they can explore whether students believe that attributing their failure to effort might/ might not enhance their perseverance and persistence in their learning. Researchers can also expand on previous studies by classifying attributions for failure in a specific class (e.g., in a language class for writing, reading, listening, or speaking). Next, they can develop questionnaire items from the components of attributions (e.g., ability, effort, luck, or task difficulty) as displayed in the model and then survey students. Conducting research that specifically explores attributions for learning failure in across disciplines might be crucial, because, for example, “failure in learning a second language is very common, and the way people process these failures is bound to have a powerful general impact” (Dörnyei, 2001, p. 119). In addition, studies can be conducted in English as a foreign language (EFL) and other settings in which “learner attributions, perceived causes of success and failure, have received little attention…” (Peacock, 2010, p. 184).

Conclusion

It might be challenging for some people to make attributions for their failure in the past, as it requires reflective capabilities. Regardless of that challenge, there are possibilities for using components of attribution theory (e.g., locus, controllability, effort) as a foundation for teachers and students to explain and mitigate academic success or failure.

References

Banks, M., & Woolfson, L. (2008). Why do students think they fail? The relationship between attributions and academic self-perceptions. British Journal of Special Education, 35(1), 49–56.

Chedzoy, S., & Burden, R. (2009). Primary school children’s reflections on Physical Education lessons: An attributional analysis and possible implications for teacher action. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 4, 185–193.

Dasborough, M. T., & Harvey, P. (2016). Attributions. Oxford Bibliography. https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780199846740/obo-9780199846740-0106.xml

David, L. (2019, February 2). Summaries of learning theories and models. https://www.learning-theories.com/

Demetriou, C. (2011). The attribution theory of learning and advising students on academic probation. NACADA Journal, 31(2), 16–21.

Dörnyei, Z. (Ed.). (2001). Motivational strategies in the language classroom [PDF file]. Cambridge University Press.

Ellis, R. (2015). Understanding second language acquisition (2nd ed.) [PDF file]. Oxford University Press.

Farid, M. F., & Akhter, M. (2017). Causal attribution beliefs of success and failure: A perspective from Pakistan. Bulletin of Educational and Research, 39(3), 105–115.

Farid, M. F., & Iqbal, H. M. (2012). Causal attribution beliefs among school students in Pakistan. Interdisciplinary Journal of Contemporary Research in Business, 4(2), 411–424.

Gobel, P., Thang, S. M., Sidhu, G. K., Oon, S. I., & Chan, Y. F. (2013). Attributions to success and failure in English language learning: A comparative study of urban and rural undergraduates in Malaysia. Asian Social Science, 9(2), 53–62.

Hsieh, P. P., & Schallert, D. L. (2008). Implications from self-efficacy and attribution theories for an understanding of undergraduates’ motivation in a foreign language course. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 33, 513–532.

Mali, Y. C. G. (2015). Students’ attributions on their English speaking enhancement. Indonesian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 4(2), 32-43.

Mori, S., Gobel, P., Thepsiri, K., & Pojanapunya, P. (2010). Attributions for performance: A comparative study for Japanese and Thai university students. JALT Journal, 32(1), 5–28.

Peacock, M. (2010). Attribution and learning English as a foreign language. ELT Journal, 64(2), 184–193.

Rasekh, A. E., Zabihi, R., & Rezazadeh, M. (2012). An application of Weiner’ s attribution theory to the self-perceived communication competence of Iranian intermediate EFL learners. Elixir International Journal, 47, 8693–8697.

Thang, S. M., Gobel, P., Mohd. Nor, N. F., & Suppiah, V. L. (2011). Students’ attributions for success and failure in the learning of English as a second language: A comparison of undergraduates from six public universities in Malaysia. Pertanika Journal of Social Sciences & Humanities, 19(2), 459–474.

Tse, L. (2000). Student perceptions of foreign language study: A qualitative analysis of foreign language autobiographies. The Modern Language Journal, 84(1), 69–84.

Vispoel, W. P., & Austin, J. R. (1995). Success and failure in junior high school: A critical incident approach to understanding students’ attributional beliefs. American Educational Research Journal, 32(2), 377–412.

Weiner, B. (1972). Attribution theory, achievement motivation, and the educational process. Review of Educational Research, 42(2), 203-215.

Weiner, B. (1976). An attributional approach for educational psychology. Review of Research in Education, 4, 179–209.

Weiner, B. (1985). An attribution theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychological Review, 92(4), 548-573.

Williams, M., Burden, R. L., Poulet, G. M. A., & Maun, I. C. (2004). Learners’ perceptions of their successes and failures in foreign language learning. The Language Learning Journal, 30(1), 19-29.

Yılmaz, C. (2012). An investigation into Turkish EFL students’ attributions in reading comprehension. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 3(5), 823–828.