5.6 The Gestalt Principles of Perception

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the figure-ground relationship

- Define Gestalt principles of grouping

- Describe how perceptual set is influenced by an individual’s characteristics and mental state

In the early part of the 20th century, Max Wertheimer published a paper demonstrating that individuals perceived motion in rapidly flickering static images—an insight that came to him as he used a child’s toy tachistoscope. Wertheimer, and his assistants Wolfgang Köhler and Kurt Koffka, who later became his partners, believed that perception involved more than simply combining sensory stimuli. This belief led to a new movement within the field of psychology known as Gestalt psychology. The word gestalt literally means form or pattern, but its use reflects the idea that the whole is different from the sum of its parts. In other words, the brain creates a perception that is more than simply the sum of available sensory inputs, and it does so in predictable ways. Gestalt psychologists translated these predictable ways into principles by which we organize sensory information. As a result, Gestalt psychology has been extremely influential in the area of sensation and perception (Rock & Palmer, 1990).

Gestalt perspectives in psychology represent investigations into ambiguous stimuli to determine where and how these ambiguities are being resolved by the brain. They are also aimed at understanding sensory and perception as processing information as groups or wholes instead of constructed wholes from many small parts. This perspective has been supported by modern cognitive science through fMRI research demonstrating that some parts of the brain, specifically the lateral occipital lobe, and the fusiform gyrus, are involved in the processing of whole objects, as opposed to the primary occipital areas that process individual elements of stimuli (Kubilius, Wagemans & Op de Beeck, 2011).

One Gestalt principle is the figure-ground relationship. According to this principle, we tend to segment our visual world into figure and ground. Figure is the object or person that is the focus of the visual field, while the ground is the background. As the figure below shows, our perception can vary tremendously, depending on what is perceived as figure and what is perceived as ground. Presumably, our ability to interpret sensory information depends on what we label as figure and what we label as ground in any particular case, although this assumption has been called into question (Peterson & Gibson, 1994; Vecera & O’Reilly, 1998).

The concept of figure-ground relationship explains why this image can be perceived either as a vase or as a pair of faces.

Another Gestalt principle for organizing sensory stimuli into meaningful perception is proximity. This principle asserts that things that are close to one another tend to be grouped together, as the figure below illustrates.

The Gestalt principle of proximity suggests that you see (a) one block of dots on the left side and (b) three columns on the right side.

How we read something provides another illustration of the proximity concept. For example, we read this sentence like this, notl iket hiso rt hat. We group the letters of a given word together because there are no spaces between the letters, and we perceive words because there are spaces between each word. Here are some more examples: Cany oum akes enseo ft hiss entence? What doth es e wor dsmea n?

We might also use the principle of similarity to group things in our visual fields. According to this principle, things that are alike tend to be grouped together (figure below). For example, when watching a football game, we tend to group individuals based on the colors of their uniforms. When watching an offensive drive, we can get a sense of the two teams simply by grouping along this dimension.

When looking at this array of dots, we likely perceive alternating rows of colors. We are grouping these dots according to the principle of similarity.

Two additional Gestalt principles are the law of continuity (or good continuation) and closure. The law of continuity suggests that we are more likely to perceive continuous, smooth flowing lines rather than jagged, broken lines (figure below). The principle of closure states that we organize our perceptions into complete objects rather than as a series of parts (figure below).

Good continuation would suggest that we are more likely to perceive this as two overlapping lines, rather than four lines meeting in the center.

Closure suggests that we will perceive a complete circle and rectangle rather than a series of segments.

According to Gestalt theorists, pattern perception, or our ability to discriminate among different figures and shapes, occurs by following the principles described above. You probably feel fairly certain that your perception accurately matches the real world, but this is not always the case. Our perceptions are based on perceptual hypotheses: educated guesses that we make while interpreting sensory information. These hypotheses are informed by a number of factors, including our personalities, experiences, and expectations. We use these hypotheses to generate our perceptual set. For instance, research has demonstrated that those who are given verbal priming produce a biased interpretation of complex ambiguous figures (Goolkasian & Woodbury, 2010).

Template Approach

Ulrich Neisser (1967), author of one of the first cognitive psychology textbook suggested pattern recognition would be simplified, although abilities would still exist, if all the patterns we experienced were identical. According to this theory, it would be easier for us to recognize something if it matched exactly with what we had perceived before. Obviously the real environment is infinitely dynamic producing countless combinations of orientation, size. So how is it that we can still read a letter g whether it is capitalized, non-capitalized or in someone else hand writing? Neisser suggested that categorization of information is performed by way of the brain creating mental templates, stored models of all possible categorizable patterns (Radvansky & Ashcraft, 2014). When a computer reads your debt card information it is comparing the information you enter to a template of what the number should look like (has a specific amount of numbers, no letters or symbols…). The template view perception is able to easily explain how we recognize pieces of our environment, but it is not able to explain why we are still able to recognize things when it is not viewed from the same angle, distance, or in the same context.

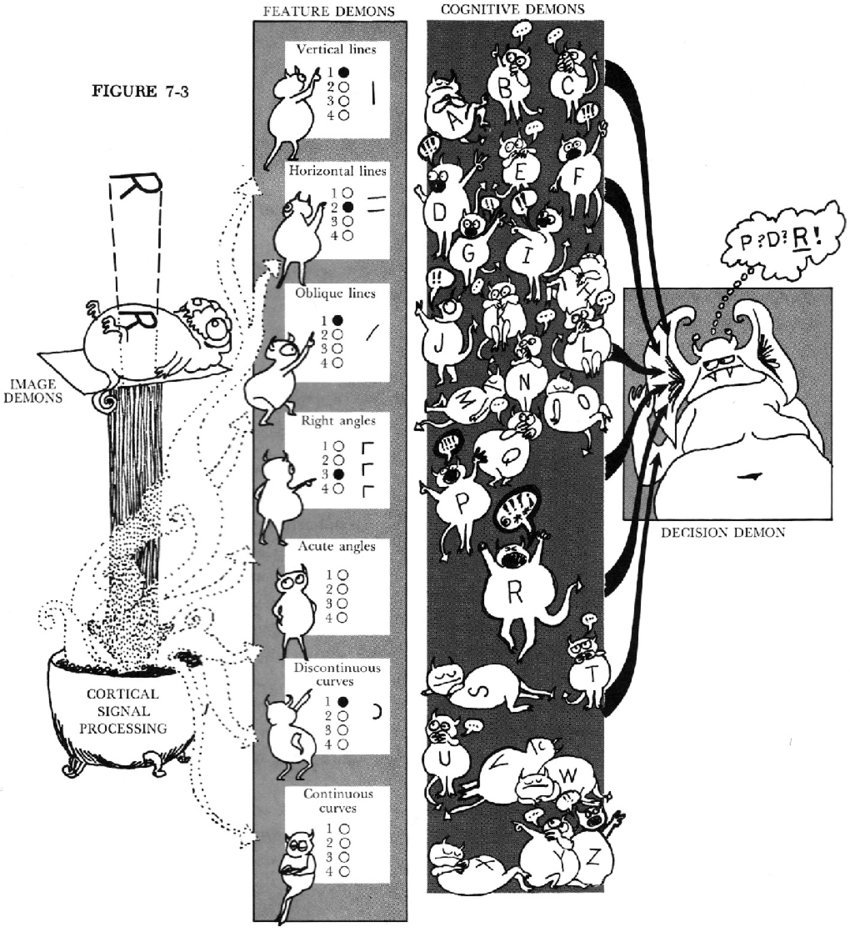

In order to address the shortfalls of the template model of perception, the feature detection approach to visual perception suggests we recognize specific features of what we are looking at, for example the straight lines in an H versus the curved line of a letter C. Rather than matching an entire template-like pattern for the capital letter H, we identify the elemental features that are present in the H. Several people have suggested theories of feature-based pattern recognition, one of which was described by Selfridge (1959) and is known as the pandemonium model suggesting that information being perceived is processed through various stages by what Selfridge described as mental demons, who shout out loud as they attempt to identify patterns in the stimuli. These pattern demons are at the lowest level of perception so after they are able to identify patterns, computational demons further analyze features to match to templates such as straight or curved lines. Finally at the highest level of discrimination, cognitive demons which allow stimuli to be categorized in terms of context and other higher order classifications, and the decisions demon decides among all the demons shouting about what the stimuli is which while be selected for interpretation.

Selfridge’s pandemonium model showing the various levels of demons which make estimations and pass the information on to the next level before the decision demon makes the best estimation to what the stimuli is. Adapted from Lindsay and Norman (1972).

Although Selfridges ideas regarding layers of shouting demons that make up our ability to discriminate features of our environment, the model actually incorporates several ideas that are important for pattern recognition. First, at its foundation, this model is a feature detection model that incorporates higher levels of processing as the information is processed in time. Second, the Selfridge model of many different shouting demons incorporates ideas of parallel processing suggesting many different forms of stimuli can be analyzed and processed to some extent at the same time. Third and finally, the model suggests that perception in a very real sense is a series of problem solving procedures where we are able to take bits of information and piece it all together to create something we are able to recognize and classify as something meaningful.

In addition to sounding initially improbable by being based on a series of shouting fictional demons, one of the main critiques of Selfridge’s demon model of feature detection is that it is primarily a bottom-up, or data-driven processing system. This means the feature detection and processing for discrimination all comes from what we get out of the environment. Modern progress in cognitive science has argued against strictly bottom-up processing models suggesting that context plays an extremely important role in determining what you are perceiving and discriminating between stimuli. To build off previous models, cognitive scientist suggested an additional top-down, or conceptually-driven account in which context and higher level knowledge such as context something tends to occur in or a persons expectations influence lower-level processes.

Finally the most modern theories that attempt to describe how information is processed for our perception and discrimination are known as connectionist models. Connectionist models incorporate an enormous amount of mathematical computations which work in parallel and across series of interrelated web like structures using top-down and bottom-up processes to narrow down what the most probably solution for the discrimination would be. Each unit in a connectionist layer is massively connected in a giant web with many or al the units in the next layer of discrimination. Within these models, even if there is not many features present in the stimulus, the number of computations in a single run for discrimination become incredibly large because of all the connections that exist between each unit and layer.

The Depths of Perception: Bias, Prejudice, and Cultural Factors

In this chapter, you have learned that perception is a complex process. Built from sensations, but influenced by our own experiences, biases, prejudices, and cultures, perceptions can be very different from person to person. Research suggests that implicit racial prejudice and stereotypes affect perception. For instance, several studies have demonstrated that non-Black participants identify weapons faster and are more likely to identify non-weapons as weapons when the image of the weapon is paired with the image of a Black person (Payne, 2001; Payne, Shimizu, & Jacoby, 2005). Furthermore, White individuals’ decisions to shoot an armed target in a video game is made more quickly when the target is Black (Correll, Park, Judd, & Wittenbrink, 2002; Correll, Urland, & Ito, 2006). This research is important, considering the number of very high-profile cases in the last few decades in which young Blacks were killed by people who claimed to believe that the unarmed individuals were armed and/or represented some threat to their personal safety.

SUMMARY

Gestalt theorists have been incredibly influential in the areas of sensation and perception. Gestalt principles such as figure-ground relationship, grouping by proximity or similarity, the law of good continuation, and closure are all used to help explain how we organize sensory information. Our perceptions are not infallible, and they can be influenced by bias, prejudice, and other factors.

References:

Openstax Psychology text by Kathryn Dumper, William Jenkins, Arlene Lacombe, Marilyn Lovett and Marion Perlmutter licensed under CC BY v4.0. https://openstax.org/details/books/psychology

Exercises

Review Questions:

1. According to the principle of ________, objects that occur close to one another tend to be grouped together.

a. similarity

b. good continuation

c. proximity

d. closure

2. Our tendency to perceive things as complete objects rather than as a series of parts is known as the principle of ________.

a. closure

b. good continuation

c. proximity

d. similarity

3. According to the law of ________, we are more likely to perceive smoothly flowing lines rather than choppy or jagged lines.

a. closure

b. good continuation

c. proximity

d. similarity

4. The main point of focus in a visual display is known as the ________.

a. closure

b. perceptual set

c. ground

d. figure

Critical Thinking Question:

1. The central tenet of Gestalt psychology is that the whole is different from the sum of its parts. What does this mean in the context of perception?

2. Take a look at the following figure. How might you influence whether people see a duck or a rabbit?

Personal Application Question:

1. Have you ever listened to a song on the radio and sung along only to find out later that you have been singing the wrong lyrics? Once you found the correct lyrics, did your perception of the song change?

Glossary:

closure

figure-ground relationship

Gestalt psychology

good continuation

pattern perception

perceptual hypothesis

principle of closure

proximity

similarity

Key Takeaways

Review Questions:

1. C

2. A

3. B

4. D

Critical Thinking Question:

1. This means that perception cannot be understood completely simply by combining the parts. Rather, the relationship that exists among those parts (which would be established according to the principles described in this chapter) is important in organizing and interpreting sensory information into a perceptual set.

2. Playing on their expectations could be used to influence what they were most likely to see. For instance, telling a story about Peter Rabbit and then presenting this image would bias perception along rabbit lines.

Glossary:

closure: organizing our perceptions into complete objects rather than as a series of parts

figure-ground relationship: segmenting our visual world into figure and ground

Gestalt psychology: field of psychology based on the idea that the whole is different from the sum of its parts

good continuation: (also, continuity) we are more likely to perceive continuous, smooth flowing lines rather than jagged, broken lines

pattern perception: ability to discriminate among different figures and shapes

perceptual hypothesis: educated guess used to interpret sensory information

principle of closure: organize perceptions into complete objects rather than as a series of parts

proximity: things that are close to one another tend to be grouped together

similarity: things that are alike tend to be grouped together

Review Questions

According to the principle of ________, objects that occur close to one another tend to be grouped together.

- similarity

- good continuation

- proximity

- closure

Our tendency to perceive things as complete objects rather than as a series of parts is known as the principle of ________.

- closure

- good continuation

- proximity

- similarity

According to the law of ________, we are more likely to perceive smoothly flowing lines rather than choppy or jagged lines.

- closure

- good continuation

- proximity

- similarity

The main point of focus in a visual display is known as the ________.

- closure

- perceptual set

- ground

- figure

Critical Thinking Question

The central tenet of Gestalt psychology is that the whole is different from the sum of its parts. What does this mean in the context of perception?

Take a look at the following figure. How might you influence whether people see a duck or a rabbit?

Answer: Playing on their expectations could be used to influence what they were most likely to see. For instance, telling a story about Peter Rabbit and then presenting this image would bias perception along rabbit lines.

Personal Application Question

Have you ever listened to a song on the radio and sung along only to find out later that you have been singing the wrong lyrics? Once you found the correct lyrics, did your perception of the song change?

Glossary

- closure: organizing our perceptions into complete objects rather than as a series of parts

- figure-ground relationship: segmenting our visual world into figure and ground

- Gestalt psychology: field of psychology based on the idea that the whole is different from the sum of its parts

- good continuation: (also, continuity) we are more likely to perceive continuous, smooth flowing lines rather than jagged, broken lines

- pattern perception: ability to discriminate among different figures and shapes

- perceptual hypothesis: educated guess used to interpret sensory information

- principle of closure: organize perceptions into complete objects rather than as a series of parts

- proximity: things that are close to one another tend to be grouped together

- similarity: things that are alike tend to be grouped together