Module 9: Moved to Action by a Higher Power: The Psychology of Religion and Motivated Behavior

Module Overview

In Module 9 we will discuss motivated behavior related to religiosity. Our discussion will tackle why people subscribe to religious belief, when and why conversion and deconversion occur, religiously motivated moral behavior, coping with life’s demands through religion, attachment to God, and finally religion and death. Our focus will be on what the literature reveals to us, thanks to the use of the scientific method and we will link to content already covered and hint at topics to be discussed in Modules 10-15.

Module Outline

- 9.1. What is Religion and to What Extent Are People Motivated by or Toward It?

- 9.2. Why Are People Motivated to Religious Ends?

- 9.3. What Is Religious Conversion and Deconversion?

- 9.4. Does Religion Motivate Moral Behavior?

- 9.5. How Does Religion Aid with Coping and Adjustment?

- 9.6. Is There a Link Between Religion and Attachment?

- 9.7. Religion and Death

Module Learning Outcomes

- Define religion and describe the dimensions of religious belief.

- State possible reasons why someone may become religious.

- State reasons why someone may convert to a different religion or deconvert from religion.

- Clarify how religion motivates moral behavior.

- Demonstrate how religion helps with coping and adjustment.

- Clarify whether religion affects attachment.

- Elaborate on religion’s role in death and mortality salience focusing on TMT and NDEs.

9.1. What is Religion and to What Extent Are People Motivated by or Toward It?

Section Learning Objectives

- Estimate how pervasive religion is in the world.

- Define spirituality.

- Define religion.

- List and describe dimensional approaches to religious belief.

- Describe the three orientations related to religious belief.

9.1.1. The Universality of Religious Belief?

Religious belief is one of the most important and personal belief systems a person may be motivated to adopt and maintain. It should be of no surprise that it is one of, if not the most important, social institution across societies, whether the person lives in a western nation like the United States, Asia, or an African tribe. According to estimates from 2010 and published in The World Factbook by the Central Intelligence Agency, 83.6% of the world’s population maintains some religious belief. Of this group of faithful, 31.4% are Christian, 23.2% are Muslim, 15% are Hindu, 7.1% are Buddhist, 5.9% subscribe to folk religions, 0.8% are listed as other, and 0.2% are Jewish. Another 16.4% are listed as unaffiliated. (Note: For a more specific country-by-country breakdown, please see the World Factbook report – web address below.) In the United States, estimates in this report from 2014 show the following pattern: 46.5% are Protestant, 20.8% are Roman Catholic, 1.9% are Jewish, 1.6% are Mormon, 0.9% are considered other Christian, 0.9% are Muslim, 0.8% are Jehovah’s Witness, 0.7% are Buddhist, 0.7% are Hindu, 1.8% listed as other, and finally 22.8% who are unaffiliated. The Pew Research Center breaks down the number of unaffiliated further as such: 3.1% atheist, 4.0% agnostic, and 15.8% subscribing to no particular belief (http://www.pewforum.org/religious-landscape-study/). These numbers clearly illustrate the global presence of religion.

9.1.2. Defining Religion

This leads to the question of what religion is. If we consider the sheer number of ways religion can be expressed, one quickly realizes there is not a blanket definition to fit all forms it can take. Religion is quite complex, composed of many parts that help to make it what it is. This includes rituals, holy books, emotions, holidays, and doctrine to name a few. The many combinations of these elements make it impossible to put one’s finger on a concrete form of religion. One thing that is certain about religion is that it is not reserved for the ‘civilized’ world but can be found in various forms everywhere on our planet. In that respect it is a universal element of all human experience. Further, it must be distinguished from spirituality, in that religion has spirituality as its base. Spirituality may be considered a belief in supernatural forces used to answer questions of how the universe works, man’s place and purpose, the existence of a higher power and a soul, and the origin of evil and suffering.

Although it is difficult to pinpoint an exact definition of religion, a very broad one may be sufficient. Religion can be considered a universal attempt by philosophically or spiritually like-minded people to set out to explain the cosmology of the universe and their concept of a divine power through common conceptions and beliefs. This highlights the social and universal aspects of religion. It is social, in that, other people are part of the search to understand a higher power, and universal insofar as virtually all humans endeavor to find this creator- being or force.

Having a religion necessitates someone be religious. Being religious implies that a person has found common ground with others on what the deity is, what the purpose of life is, and how we should live our lives. It also implies that all doubts have been cancelled, either because the person sees the religion as proof that there is a deity or holy books validate their beliefs.

9.1.3. Dimensional Approaches to Religious Belief

Religion can be seen to include different dimensions. According to Verbit (1970), six components make up religion to include community or being involved with others who share the same beliefs, knowledge or being familiar on an intellectual level with the tenets of one’s faith, ritual or ceremonial behavior that is undertaken either publically or privately, emotion or feeling love or fear, doctrine or statements about one’s relationship with the higher power, and ethics or a set of rules which govern our behavior on a daily basis and help us to identify right from wrong. Verbit (1970) also notes that these components vary along four dimensions to include intensity or how deeply committed one is, frequency or how often the components are engaged in, content or the component’s essential nature such as specific rituals or knowledge, and centrality or the salience of the component.

Glock (1962) produced a list of five dimensions of religiousness to include beliefs, feelings, practices, knowledge, and effects. Beliefs include the actual ideology the person subscribes too, its tenets, the degree to which the person holds this attitude, and the salience of the belief. Feelings refer to the inner emotional world of the individual and includes one’s fear about not being religious or committing immoral acts that could lead to an afterlife in Hell or the joy that one develops in his/her well-being for being believing and being a devoted follower. Feelings reflect an experiential dimension. Practices include any ritualistic behavior the person engages in due to the religion itself and may include praying, attending church services, fasting, engaging in communion, or other practices unique to a specific faith. Knowledge includes what information the person has concerning their faith, such as the history of their religion. This dimension is not required to be committed to the faith and many adherents subscribe to the tenets of the religion without knowing where they came from. Finally, effects refer to the consequences of one’s steadfast belief in the tenets of his/her faith in other life domains. For instance, an individual may choose not to lie or take advantage of others due to their religion. You could say that expressions such as ‘What would Jesus do?’ demonstrate this. Jesus’s actions in a given situation are not actually part of the religious practice of Christianity but we can use this as a guide to figure out how to live our life in a manner consistent with our faith.

Hunt (1972) indicated that religion can take three forms. Literal religion occurs when the individual takes a religious statement at face value and does not question it. Antiliteral religion reflects a rejection of the statements made by literalists. Finally, mythological religion is when we reinterpret religious statements to discover their deeper symbolic meaning(s). Finally, Fromm (1950) described humanistic religion as involving man and his strength, virtue as self-realization, and a rejection of obedience which contrasts with authoritarian religion and its emphasis on obedience.

These are just a few examples of ways to describe or classify what it means to be part of a religion or to be religious.

9.1.4. Religious Orientation

A person can express one of three different religious orientations: intrinsic, extrinsic, or quest. First, intrinsic religiosity (Allport, 1959) is a deep, personal religious belief and the individual can best be described as unselfish, altruistic, centered on faith, believing in a loving and forgiving God, anti-prejudicial, seeing people as individuals, and accepting without any reservations. Second, extrinsic religiosity (Allport, 1959) is called upon when needed as in times of crisis, is not part of the person’s daily life, the individual sees faith and belief as superficial, religion is viewed as a means to an end, God is seen as punitive and stern, and the person believes they are under external control. The focus of the extrinsically religious might be on such things as going to lunch after church, being with other people, and participating in church activities. Finally, the quest orientation, originated by Daniel Batson at the University of Kansas (1993), describes a person who is ready to face existential questions and looks for ‘truth,’ views religious doubt as positive, is open to change, and is humanitarian. Although these questions are faced, no reduction in the complexity of life is arrived at.

So how might these religious orientations relate to personality traits as defined by the five-factor model as discussed in Module 7? Cook, McDaniel, & Doyle-Portillo (2018) found that individuals high in intrinsic religiosity were generally more agreeable and conscientious and less neurotic. Those high in quest orientation were less agreeable and conscientious and more neurotic. Other research shows that intrinsic religiosity is associated with lower levels of body dissatisfaction and eating disorders compared to extrinsic religiosity (Weinberger-Litman, 2016) as well as better mental health (Mahmoodabad et al., 2016), quest orientation is linked to mystical orientation (Francis, Village, & Powell, 2017), extrinsic religiosity can protect against the effects of depressive symptoms and individuals are, therefore, less likely to use tobacco when depressed (Parenteau, 2018), quality of life of male addicts can be improved by strengthening the extrinsic motivation for religion (Nafiseh et al., 2016), and finally sleep quality is better in college students who express intrinsic religiosity (Hasan et al., 2017).

9.2. Why Are People Motivated to Religious Ends?

Section Learning Objectives

- Define faith and describe its salience in light of the question of why people are religious.

- Differentiate the function of the personal and collective unconscious and the effect on religious belief.

- Describe specific archetypes.

- Describe how religion could be viewed as deprivation by examining psychoanalysis.

- Clarify how religious belief may be motivated by fear.

- Clarify how religious belief may be motivated by a desire to be more.

- Clarify how religious belief may be motivated by survival.

- Contrast research on religion as nature and religion as nurture.

Probably the most fundamental question we can ask about religion is why people are religious in the first place. Consider that religious belief hinges on faith, which can be defined as belief in the absence of proof. If mankind is a rational being, then belief when no proof exists (at least at the time) is illogical and contradictory to our nature. Still, humans believe in that which they cannot see. This begs the question of why and a few possible answers are proposed.

9.2.1. The Collective Unconscious and Archetypes

It might be that human beings express religiosity to better understand the universe they live in. Carl Jung divided the psyche into three distinct parts. The first is the ego which he says is the conscious mind and chooses which thoughts, feelings, or memories can enter consciousness. The second part is the personal unconscious which includes anything which is unconscious but can be brought into consciousness. It includes memories which can be easily remembered and those that have been repressed. Jung talks about complexes which are groups of experiences in the personal unconscious. The complex can include thoughts, feelings, and memories concerning a particular concept such as the mother (Jung, 1934). The final, and maybe the most important part, is the collective unconscious (Jung, 1936). It is the innate knowledge that we come into this world with. It might be called our psychic inheritance. We are never aware of it despite it influencing all our experiences and behaviors. It is shared by all members of a culture or universally, by all humanity. The collective unconscious is not a personal acquisition and cannot be regarded as such.

The collective unconscious consists of archetypes (Jung, 1936), which are unlearned tendencies that allow us to experience life in a specific way. They act as organizing principles despite not having a form of their own. Archetypes can best be understood as images, patterns, and symbols that can be found in dreams, religion, ritual, art, literature, mythology, and fairy tales. The way in which archetypes are sensed is unique to the person and draws off their total experience, despite the archetype being universal. Some archetypes are:

- Mother Archetype – All of us born into this world came in looking for a nurturing figure to guide us through the early years of our life. This is true of present-day man, all the way back to the first baby that was born. Of course, this figure is our mother. In mythology, it is symbolized by the “earth mother” or Eve in western religion. Also, less personal examples as the church, a nation, forest, or the ocean can be included. Jung suggested that the person who did not have the support of their mother as they grew up may seek comfort in the church, in a life at sea, or identifying with the “motherland.”

- Shadow Archetype – The shadow comes from our pre-human, animal past, when our only goal was survival and reproduction. As well, during this time we possessed no self-conscious emotions. It is neither good or bad and is symbolized as a snake, dragon, demon, or a monster.

- Anima/Animus Archetypes – The anima is the female aspect of males, and the animus is the male aspect of women. Greek mythology has suggested that we spend our lives looking for our other half. When we experience love at first sight it is because we have found the person who fills the missing half.

- Child Archetype – The child archetype is represented in mythology, mostly by infants, but also by small creatures. The Christ child is a manifestation of the child archetype.

- Animal Archetype – The animal archetype represents the bond humanity shares with the animal kingdom. Snakes, often thought to be particularly wise, are an example of this archetype.

- God Archetype – Man’s need to comprehend the universe and to assign a meaning to all that happens is said to be a byproduct of the God archetype. In doing so, we seek to know the purpose and direction behind all actions

The God archetype is of particular interest. Religion helps elucidate some of the more nebulous questions about life (i.e., what is the nature of the universe, is there really a God, do we have a soul that lives on, and what is the source of evil and suffering?). By making the unclear clear, religion gives people a sense of meaning and purpose, and the universality of religion as shown at the beginning of this module makes sense in light of the collective unconscious and archetypes. But this is just one explanation.

9.2.2. Religious Belief, Motivated by Deprivation?

Sigmund Freud, father of psychoanalysis, viewed religion as an illusion and an attempt at wish fulfillment. He thought that the adoption of religion was a reversion to childish patterns of thought due to feeling helpless and guilty. Human beings strive to feel secure and to forgive; they acquire both by inventing the idea of God. He examined religion at the cultural level and said it attempts to subdue our antisocial tendencies and control our selfish and aggressive impulses. A personal level was also important to Freud and through it, we can control our inappropriate social behaviors, but this control creates neurosis since these behaviors are natural tendencies that we are limiting the expression of.

Alfred Adler (1927; 1954) discussed what he called inferiority feelings and said they serve as a motivating force in behavior. Originating in infancy, a child depends on caregivers for everything which leads to a state of helplessness and dependency on others. This awakens a sense of inferiority, and the child is aware of the need to overcome it. At the same time, they are driven to the betterment of the self. Inferiority feelings operate to the advantage of the individual and society, as they lead to continuous improvement. So, we are motivated by a goal for superiority, or to be competent in all that we do. Failure to compensate for inferiority feelings can lead to the development of an inferiority complex, which renders the person incapable of coping with life’s problems. We could develop a superiority complex in which we exaggerate our own importance. Both complexes involve overcompensation in which the person denies the real-life situation, rather than accept it. The person may also develop a belief in an omnipotent god to relieve some of this inferiority and to serve as a source of great power.

Finally, Karen Horney (1945) saw the challenge of life to be relating effectively to others. Basic anxiety is a feeling of pervasive loneliness and helplessness which is the foundation of neuroses and she said that all the negative factors in a child’s environment that can cause such insecurity are basic evils. These conditions include dominance, lack of protection and love, erratic behavior, parental discord, and hostility. They undermine the child’s security and lead to basic hostility. Children are driven to seek security, safety, and freedom from fear in a threatening world, and one potential source of this security could be a higher power.

9.2.3. Religious Belief, Motivated by Fear?

Uncertainty about the world has been shown to lead to worrying (Dugas, Gosselin, & Ladouceur, 2001). It is fair to say that the thought of our death and whether an afterlife exists, can lead to fear of the unknown or worry. This fear creates an uncomfortable feeling which we are motivated to get rid of. If thoughts of God and Heaven occur and this fear subsides, then according to operant conditioning theory, we will bring these concepts to mind the next time such fear arises. Simply, this is the essence of negative reinforcement, or if an action (i.e., thinking about God and Heaven) takes away something aversive (i.e., fear/worry about death and the afterlife) we will be more likely to engage in that behavior in the future if the aversive stimulus presents itself. In negative reinforcement, we can escape this aversive stimulus or think about God when worrying about dying or we can avoid the fear/worry by just thinking about God and Heaven.

So, is there truth to this? Flannelly (2017) reports that Americans who display an internal religious motivation, or see religion as an end in itself, have lower death anxiety than those who adopt an external religious motivation and see religion as a way to achieve social goals. Furthermore, belief in an afterlife is negatively associated with fear of death. Krause (2015) found that people who go to church receive more support from fellow churchgoers, and as a result, are more likely to trust God and feel forgiven by him. This leads to the individual experiencing less death anxiety. Finally, age is a critical factor and death anxiety has been shown to be greater among younger and middle age adults. A religious sense of hope reduces this anxiety as people get older (Krause, Pargament, & Ironson, 2017).

9.2.4. Religious Belief, Motivated to Be More?

In Module 8, we discussed Abraham Maslow’s concept of the hierarchy of needs and how at the top of the pyramid were self-actualization needs, which are called B-needs or being needs. According to Maslow (1970), self-actualization was expressed during moments of intellectual and emotional enlightenment, called peak experiences. It is from these experiences that religions can be built. Therefore, his position is one of growth, opposite of Freud’s view of religion, as arising out of deprivation.

We might even say that where religion is concerned, we are motivated to know more. How so? Maslow (1970) suggested the existence of the needs to know and understand, in which the former is more potent than the latter, and occurs prior to it. Recall the discussion of uncertainty about the unknown in Section 9.2.3. and how it can lead to fear, which we are motivated to reduce or avoid. You might say belief in God and the afterlife avoids this uncertainty (and subsequent fear) because it creates knowledge. If we are knowledgeable then we cannot be uncertain, resolving this problem.

9.2.5. Religious Belief, Motivated by Survival?

Edward O. Wilson proposed the concept of sociobiology, defined as “the systematic study of the biological basis of all forms of social behavior, in all kinds of organisms, including man” (Wilson, 1978). He believed that religion was an “enabling mechanism for survival” and any practices that make the survival of the species more likely, will lead to physiological controls that favor the acquisition of those practices. Prosocial behavior is an example of a practice that leads to the survival of the group and has been linked to psychological flourishing (Nelson et al., 2016), improved physical health (Brown & Brown, 2015), fewer problem behaviors in teens (Padilla-Walker, Carlo, & Bielson, 2015), reduced stress levels (Raposa, Laws, & Ansell, 2015), and increased longevity (Hilbrand et al., 2017).

9.2.6. Religion as Nature

Is it possible that people are predisposed to religious belief due to actions of genes, reflecting the role of nature? Bouchard et al. (1990) investigated this issue by following more than 100 sets of twins reared apart and a larger sample of twins raised together. Results showed a strong heritable component to religiosity, and that family environments (nurture) tended not to be very influential on this belief. Koening and Bouchard (2006) found that 40 to 60% of the observed variation in the personality traits of religiousness, authoritarianism, and conservatism came from genotypic variation. But these findings are controversial at best, and in fact, most research points to the fact that our experiences shape who we are as we grow up.

9.2.7. Religion as Nurture

Zhang (2003) used a study of 232 senior high school students and their parents from Mainland China to explore the question of whether parent’s and children’s thinking styles are related. The results of the study showed that children’s scores on thinking styles were significantly correlated with both socialization factors, reported by the children, and the thinking styles of their parents. This was the case on six of eleven thinking styles. Zhang notes that, “Parents could pay more attention to how they deal with the various issues and tasks in daily life, as their close relationship influences how their children deal with the outside world” (Zhang, 2003, pp. 627-628). This study shows that a definite socialization process is ongoing between parents and their children. Just as thinking styles can be socialized, so too can religious beliefs.

Grusec and Goodnow (1994) presented a model of how the socialization process may work. First, children must perceive parent’s values either accurately or inaccurately. Second, children either reject or accept these values. Not only do religious beliefs need to be transmitted to the child, but also the child needs to acquire an accurate perception of these beliefs. If they are inaccurately taken in, internalization may be more difficult. Knafo and Schwartz (2003) propose three processes that may affect accuracy including: (1) availability of parental messages, (2) the understandability of these messages, and (3) the adolescent’s motivation to attend to them.

Availability implies that parents make messages available to their children by capturing their attention and by communicating the importance of a disciplinary message to them. This may be assessed by frequency of value discussion. The more frequently parents impart their values on their children, the greater the chance that this message will be accurately taken in.

Understandability is possible if the message is clear, concise, redundant, and consistent. Most importantly, it must match the child’s current cognitive level. This means that parents may communicate more concrete aspects of religious beliefs to their children and save more abstract ones for a time when the child is able to process it. Another strategy for dealing with abstract concepts is to place them in a world of fantasy where reason is not needed. The child will at least have knowledge of the concepts, without having to find cognitive explanations for them. Understandability is affected by conflict and perception of parental agreement, both of which can impede the ability of the child to accurately perceive the message.

Finally, motivation to attend to the message is enhanced by parental consistency, the lack of an overt value conflict between parents, and perceived parental agreement. If parents are consistent, the child will be more likely to listen to the message. Also, conflict is likely to reduce the accuracy of the perception and since it elicits negative emotional reactions, it may reduce the adolescent’s motivation to listen. Finally, children who perceive their parents to be in agreement are more likely to identify with the parents. Perceived parental disagreement may cause confusion and upset the child, thereby interfering with both motivation and understanding (Knafo & Schwartz, 2003).

Hunsberger and Brown (1984) demonstrated the power of parental influence by looking at surveys from 878 Introduction to Psychology students. Differences among students from different religious traditions revealed that higher percentages of Greek or Russian Orthodox and Jewish students saw “Home” as the strongest influence on them, while Roman Catholics and Anglicans chose “School.” Protestants and Personal Religion groups chose “Other” as having the greatest influence. Finally, agnostics put “School” first and “Home” at a very close second while atheists tied between “Home” and “School” as having the greatest influence. Although there were denominational differences, “Home,” represented by parents, was reported to exert the greatest influence by 44% of all respondents. The next closest group was friends at 15%. A similar finding was reported by Hunsberger (1983) who learned that the top three who had the most influence on a person’s religious beliefs were mother first, church second, and father third. Francis and Gibson (1993) learned that mothers had more influence on their children’s religious beliefs than fathers, though there was some inclination toward stronger same-sex influence for both parents.

The study by Francis and Gibson (1993) brought up an interesting twist on the parental influence quandary: Does the father have more influence on the child than the mother? Dudley and Dudley (1986) found that the values of mothers are the best predictors of the values of their children. However, when there is disagreement between parents on religious values, children are more likely to agree with the father than the mother. Clark, Worthington, and Danser (1988) found that a father’s religious beliefs and practices, and his parenting styles were associated with father-son similarities in beliefs. If fathers attend church, discuss religion at home, and are committed to their religion, their sons will attend church with similar frequency to the fathers. This was also replicated in a study by Kieren and Munro (1987) who showed fathers to have more of an impact.

Hayes and Pittlekow (1993) showed that the effect of the mother and the father varies. For both sons and daughters, the mother who is religiously devout, tends to produce children who are equally devout. Mothers also influence their sons through disciplinary supervision. Hence, sons of strict mothers tend to be more religious later in life. For sons, fathers influence their religious beliefs through his own religious belief (similar to Clark, Worthington, & Danser, 1988). For females, the moral supervision of the father and the influence of traditional family networks and the community are important.

Upon surveying Catholic high school seniors, Benson et al. (1986) discovered that the importance of religion for parents, home religious activity, and positive family environment were the three main factors that predicted adolescent religiousness. Friedman (1985) and Slaughter-Defoe (1995) note that one’s family of origin and extended family can be very critical in affecting socialization and functioning in many different systems like religion. Furthermore, studies by Kluegel (1980), Hadaway (1980), and others have elucidated the fact that children raised within a specific familial religious denomination tend to continue identifying with this group throughout adolescence and young adulthood. Flor and Knapp (2001) reported that as parental modeling of religious behavior, parental desire for the child to be religious, and discussions of issues of faith increase, so does child religious behavior.

Okagaki and Bevis (1999) drew five main conclusions from a study they conducted. First, daughters have more accurate perceptions if their parents discuss their beliefs often and if the parents agree. Second, daughters’ perceptions of the warmth of the parent-child relationship were related to the agreement between daughter’s beliefs and their perceptions of the parent’s beliefs. Third, a daughter will more likely adopt her father’s beliefs if she believes they are important to him. Fourth, a parent’s beliefs and a daughter’s beliefs are mediated by the daughter’s perceptions of parental beliefs. Fifth, perceived agreement between parent and daughter is generally not related to the differences between the daughter’s beliefs and parental beliefs.

Hoge, Petrillo, and Smith (1982) learned that creedal assent, the agreement between parents and child on religious beliefs, is greater when there are fewer parent-child disagreements in the house, the parents are younger, the parents agree on their beliefs and have definite beliefs, and parents carry out conscious religious socialization in the home. This relationship may not be as simple as Hoge and colleagues have shown though. Dudley and Dudley (1986) concluded that a generation gap exists between youth and parents. Adolescents as a group are likely to assert their independence from their parents by becoming less traditional in their religious values, relative to parental values, though the values are still somewhat similar.

We will discuss other aspects of socialization in this module and throughout this book. At this point, I wanted to present a historical overview of what we know to show that, though nature may have a role, nurture has a much greater one.

What Do You Think?

David Elkind (1978) discovered that most children, before the age of 11 to 12, are unable to understand religious concepts as adults understand them. For instance, a little girl from Connecticut read the Lord’s Prayer as such, “Our Father who art in New Haven, Harold be thy name” (pp. 26-27). Prior to adolescence, these terms are understood in relation to the child’s own level of comprehension.

Luella Cole and Irma Hall (1970) observed that small children often show a free, unconventional imagination in their thinking about religion. Children tend to accept religious concepts told to them by their elders without any doubt about their correctness. Also, they do not question their nature. Once older, many adolescents investigate religion again as a possible source of intellectual and emotional stimulation and satisfaction. Beyond the age of 15, children become critical of their earlier beliefs but in the end, they settle down to a rather indifferent and tolerant attitude. Children, Cole and Hall say, do not use religion as adults do. For instance, religion is not used for adult values since they cannot understand them but may be used for a sense of security and relief from feelings of guilt. Adolescents do attempt to find something in religion but usually do not.

9.3. What Is Religious Conversion and Deconversion?

Section Learning Objectives

- Define religious conversion and proselyte.

- Contrast sudden and gradual conversion.

- Define deconversion and contrast it with apostasy.

- Report statistics for the extent to which people convert and deconvert.

- State reasons why people covert and deconvert.

9.3.1. Defining Terms

Religious conversion is the process of changing one’s religious beliefs. What you might have subscribed to in childhood, now changes to another set of beliefs, or you could have gone from not being religious to being religious. The person who undergoes conversion is said to be a convert or proselyte. This change occurs either suddenly or gradually (Richardson, 1985).

As you would expect, in sudden conversion the change comes quickly and the person either adopts a faith they have not previously subscribed to or make of central importance their current faith that was not important previously. Sudden conversion tends to be more emotional than rational, is permanent when it occurs, and external forces may play a key role (the effect of external motivation).

In contrast, gradual conversion takes time, as little as a few days up to several years, and may not even be noticed. Despite this, it results in the same transformation of self as the sudden conversion. It tends to be rationally driven and linked to a search for meaning and purpose in life. The person may ponder basic life questions and the answers provided by religion for them. This could be driven by a need for cognition (see Module 8). Also, internal forces are at work such that the convert is actively seeking. The conversion may not be permanent and could occur several times (Richardson, 1985).

Finally, what is deconversion? Deconversion is the process of leaving one’s faith. It should be distinguished from apostasy which is when a person completely abandons their faith and becomes nonreligious. A person who undergoes deconversion may not necessarily abandon their beliefs.

9.3.2. How Prevalent is Conversion and Deconversion?

The Pew Research Center’s Forum on Religion & Public Life conducted the 2007 Landscape Survey and did a follow up in 2011that found 44% of their sample of 2,867 respondents did not currently belong to their childhood faith. Of that 44%, 4% raised Catholic and 7% raised Protestant were now unaffiliated. Five percent of Catholics converted to Protestantism while 15% of Protestants changed to another denomination of Protestantism. Four percent that were not raised in any faith were now affiliated. In terms of being in the same faith as childhood, 56% fell into this category but 9% reported that they did change their faith at some point but returned to their childhood one. Remarkedly, 47% made no such change and remained true to their childhood religious beliefs.

The Pew Research Center points out that most people who convert do so before age 24 and many change their religion more than once. In terms of when Catholics leave their childhood faith, 79% of respondents became unaffiliated by age 24, with another 18% of 24-35-year-olds making the change. In terms of being raised Catholic but changing to Protestantism, 66% were under 24 and 26% were between 24-35 when this occurred. For Protestants who became unaffiliated, 85% were under 24 and 11% were 24-35, while for those who switched to another Protestant denomination 56% were under 24, 29% were aged 24-35, and 12% were 36-50. Finally, for those raised unaffiliated and became affiliated, 72% did this by age 24 with 19% making the change from 24-35, and 7% between age 36-50. As you can see, religious change is not very common after age 50.

9.3.3. The Motivation for Changing One’s Religion

So why do people change their religious beliefs? The 2011 survey included items to probe this question. These items consisted of closed-ended (yes-no) questions asking whether or not certain reasons were important to them but also open-ended questions where the respondent could share reasons not on the list. What were the highly endorsed common reasons?

- Catholics who are now unaffiliated – Gradually drifted away from the religion

- Catholics who became Protestants – Their spiritual need was not being met

- Protestants who are now unaffiliated – Gradually drifted away from the religion

- Protestants who switched denominations – Found a religion they liked more (58%) but note that 51% said their spiritual needs were not being met

- Unaffiliated in childhood who are now affiliated – Only two answers were selected – 51% said their spiritual needs were not being met while 46% said they found a religion they liked more

As for the open-ended questions, reasons that were given for switching religions included not believing in their former religion or any religion, scandal within their faith such as the molestation of children, looking for something deeper, and life cycle changes such as family or marriage.

Many who deconverted said they did so because they thought religious people were hypocritical and insincere and that religious organizations place too much emphasis on rules and not spirituality. Despite this, about four in ten state that religion is somewhat important in their life and leave open the possibly of joining a religion later.

For more on the 2011 report, please visit the Pew Research Center’s website at: http://www.pewforum.org/2009/04/27/faith-in-flux/

Interestingly, a 2015 report (using a sample of 35,000 U.S. adults) by the Pew Research Center shows that the U.S. public is becoming less religious, with the percentages of people saying they believe in God, pray daily, regularly go to church or other religious services, all declining. This decline is attributed in part to the Millennial generation who say they do not belong to any organized faith, though this does not mean they are nonbelievers. As the report says, “In fact, the majority of Americans without a religious affiliation say they believe in God. As a group, however, the “nones” are far less religiously observant than Americans who identify with a specific faith. And, as the “nones” have grown in size, they also have become even less observant than they were when the original Religious Landscape Study was conducted in 2007. The growth of the “nones” as a share of the population, coupled with their declining levels of religious observance, is tugging down the nation’s overall rates of religious belief and practice.”

The report also shows that 77% of those who do claim a religion, show a consistent level of religious commitment since a 2007 report, and 97% of these people continue to believe in God, “though a declining share express this belief with absolute certainty (74% in 2014, down from 79% in 2007).” Some measures also show that religiously affiliated people have grown more religious over time. For instance, there have been modest increases in the number of religiously affiliated adults who say they read scripture regularly, share their faith with others, and participate in small prayer groups or scripture study. Americans are also more spiritual, with about 6 in 10 adults now saying they feel a deep sense of “spiritual peace and well-being,” up 7% since 2007.

For more on the 2015 report, please visit the Pew Research Center’s website at: https://www.pewforum.org/2015/11/03/u-s-public-becoming-less-religious/

9.4. Does Religion Motivate Moral Behavior?

Section Learning Objectives

- Describe the effect of religiosity on various moral attitudes.

- Describe how moral development proceeds according to Kohlberg.

- Establish whether there is a link between moral behavior and religiosity in relation to cheating/dishonesty.

9.4.1. Moral Attitudes

A link between religion and moral attitudes should not really be surprising. One study examined individual religiosity and found that it was positively related to moral attitudes but that the effect was stronger in more religious countries than secular ones (Scheepers, Te Grotenhusi, & Van Der Slik, 2002). Religion has specifically been linked to support for environmental spending (Greeley, 1993), opposition to homosexuality (Deak & Saroglou, 2015; Adamczyk & Pitt, 2009), negative attitudes toward euthanasia (Bulmer, Bohnke, & Lewis, 2017; Danyliv & O’Neill, 2015), seeing suicide as unacceptable (Osafo et al., 2013; Knizek et al., 2011; Domino & Miller, 1992), moral disapproval for pornography use (Baltazar et al., 2018; Grubbs et al., 2014), disagreement over employer coverage of contraception (Patton, Hall, & Dalton, 2015), more negative attitudes toward individuals not in their faith (in this case, non-Christian groups; LaBouff et al., 2012), the use of corporal punishment by parents with their kids (Taylor et al., 2013), and showing favorable attitudes toward capital punishment (i.e., the death penalty) but only when angry and judgmental images of God are used and not when loving and engaged in the world images are presented (Bader et al., 2010).

Interestingly, Cobb-Leonard & Scott-Jones (2010) found that among a sample of high school students, the majority who reported that religion was important to them, most engaged in sexual behavior despite being aware of religious proscriptions against premarital sex, and cited relationships and physical health as the basis of their standards for being sexually active. The authors suggest that adolescents may be accepting of premarital sex if there is a committed romantic relationship. In another study, sampling only female adolescents aged 13 to 21, religiosity was a protective factor in relation to sexual behavior with those who reported being sexually active were less likely to have been pregnant, have an STD, or have multiple sexual partners (Gold et al., 2010).

9.4.2. Moral Development

Most of what we know about moral development in children comes from the pioneering work of Lawrence Kohlberg. Kohlberg (1964) said that a person’s moral stage is determined by the answers they give to hypothetical dilemmas. But for him, the reasoning behind the answers was more important than the answers themselves. He said moral development proceeded through three levels, each with two substages. How so?

Preconventional Morality

- Infants up to age 10

- Stage 1: Children obey rules because they fear being punished if they disobey

- Stage 2: Children obey because they think it is in their best interest to do so – they will receive some reward

Conventional Morality

- Begins around age 10

- Stage 3: Children obey rules, first based on conformity and loyalty to others

- Stage 4: Eventually their reasoning shifts to a “law-and-order” orientation based on an understanding of law and justice; it is what society expects

- Most people remain here

Postconventional Morality

- Most people never reach this level.

- Stage 5: Some adults realize that certain laws are themselves immoral and must be changed.

- Stage 6: Adults follow laws because they are based on universal ethical principles; any that violate these are disobeyed.

Before we move on, it should be pointed out that research shows that the sequence Kohlberg suggested occurs as he hypothesized, and that people do not skip stages (Walker, 1989).

9.4.3. Moral Behavior

Now that we know what form moral attitudes take and how moral development proceeds, let’s discuss moral behavior in regards to honesty and cheating. Before we get to religion and its link to moral behavior, we need to address whether moral identity predicts moral behavior. The results of a meta-analysis of 111 studies from fields such as business, psychology, marketing, and sociology suggest that it does. The study showed that moral identity predicted engagement in prosocial and ethical behavior and avoidance of antisocial behavior (Hertz & Krettenauer, 2016).

You would then expect that being religious will lead to moral behavior and specifically, acting honestly (or not cheating). Shariff (2015) asked the simple question of whether religion increases moral behavior, and his results produced an answer in the affirmative and showed that the religious see morality as a set of objective truths. Arbel et al. (2014) found that honesty was highest among young religious females and lowest in secular females. Another study showed the general trend also, but only when the participant viewed God as punishing and not loving (Shariff & Norenzayan, 2011). Stavrova and Siegers (2014) found that those professing to be religious disapproved of lying in their own interests and were less likely to engage in fraudulent behaviors, all while being more likely to engage in charitable work. These findings related to countries in which there is no social pressure to follow a specific faith but weaken and eventually disappear as the national level of the social enforcement of religiosity increased.

Is the relationship really this simple? Aydemir and Egilmez (2010) found that ethical behavior and honesty are positively associated with being intrinsically religiously motivated but for those who demonstrate extrinsic religiosity, the associate was negatively related.

How do we learn what moral behaviors are appropriate? As children, we were often read moral stories such as Pinocchio and The Boy Who Cried Wolf with the expectation being that they would lead to honest behavior. But is that truly the case? Lee et al. (2014) found that these stories did not reduce lying in a group of 3- to 7-year-olds but the story, George Washington and the Cherry Tree, did. Why was that? Simply, the former stories focused on the negative consequences of dishonesty while the latter story focused on the positive consequences. When the cherry tree story was changed to focus on negative consequences, it failed to promote honesty.

9.5. How Does Religion Aid with Coping and Adjustment?

Section Learning Objectives

- Revisit the stress and coping model and indicate how it relates to the discussion of religion.

- Identify the two forms religious coping takes.

- Clarify how much religious coping is too much.

- Justify the utility of religious coping.

- Describe the development of prayer.

9.5.1. A Return to Our Stress and Coping Model from Module 4

In Module 4, and then expanded in Module 5, I presented a model for stress and coping which showed us moving from a demand to assessing the costs of motivated behavior to deal with it/them and seeing if we had the resources to cover these costs, to experiencing strain if the resources are not sufficient, using problem focused coping to deal with the demand, the experience of stress if PFC does not suffice, and finally, use of emotion focused coping to manage the stress. With the stress controlled, we can either ride out our time until the demand is over or use PFC strategies to help deal with it. I presented various EFC strategies we can use and, in this section, will talk briefly about how religion can help us cope.

9.5.2. Religious Coping

So how might we use religion to help us deal with life’s demands, whether daily hassles or stressors? Religious coping can take two forms – positive or negative (Pargament et al., 1998). In positive religious coping, we might say that the event happened, or is happening, because it was part of God’s plan; we could ask God for guidance or reassurance that we will be okay; we can seek advice from a pastor, rabbi, minister, priest, etc.; and we can see God as a partner. In negative religious coping we might see the event as punishment from God, the work of Satan and evil, or might passively rely on God to fix the problem for us. Positive religious coping reflects a secure relationship or attachment with God while negative religious coping demonstrates an insecure relationship (Pargament et al., 2011). More on attachment and God later in this module.

But how much religion do you need to cope? Believe it or not, too much reliance on religion can be bad. In a 2003 study lead by Alexis Abernethy of the Fuller Theological Seminary, researchers evaluated 156 spouses of cancer patients for religious coping, symptomology related to depression, social support, self-efficacy, and how much they believed they controlled the events of their life. Results showed that levels of depression were the lowest for the spouses who used religious coping in moderation. Using religious coping excessively could lead to ignoring other useful coping mechanisms, the lead author speculated. For more on this research see the In Brief article in Monitor on Psychology (2003, Vol. 34, No 1.) by visiting:

http://www.apa.org/monitor/jan03/religion.aspx

Pargament et al. (2000) identified five major functions of religious coping to include gaining control over the situation, finding meaning, feeling a closeness with God which provides comfort, achieving closeness to others, and transforming life. It provides the most benefit for those with a stronger religious orientation (Pargament et al., 2001).

Religious coping has been shown to be helpful for those suffering from geriatric depression (Bosworth et al., 2003), provide hope to Muslim war refugees from Kosovo and Bosnia (Ai, Peterson, & Huang, 2009), aid with the management of chronic pain in older adults (Dunn and Horgas, 2004), support good mental health (Fabricatore, Handal, Rubio, & Gilner, 2009), lead to a reduction in stress symptoms related to extreme stressors such as 9/11 (Meisenhelder & Marcum, 2004), help patients adjust to a diagnosis of prostrate cancer (Gall, 2004), aid in marital adjustment (Pollard , Riggs, & Hook, 2014), and finally help patients live with HIV (Pargament et al., 2004).

9.5.3. Prayer

Another form religious coping may take is prayer. Individuals pray to help find meaning in a situation, to change events, gain control, seek help from God, and build one’s sense of self-worth. Basically, the same set of reasons discussed earlier.

So how and when does prayer develop as a form of religious coping (i.e., a type of motivated behavior to deal with demands)? Long, Elkind, and Spilka (1967) identified three stages in childhood that prayer develops through. Stage I children (aged 5-7) had a vague and indistinct notion of prayer. They were only somewhat aware that prayers are linked with the term “God” and did not exhibit a great deal of real comprehension. Children who were unaware about the nature of prayer also did not know whether dogs and cats prayed.

Stage II (7-9) prayer was now concrete. It was conceived in terms of a specific and appropriate activity. Seven-year-old Jimmy reported that prayer is used to obtain such things as water, food, rain, and snow and that it is asked of God. One interesting finding is that children did not believe that God could handle multiple prayer requests because he had a limited capacity.

Stage III (10 and up) marks the belief that prayer is a private conversation with God and was not discussed with others. Children did not believe that dogs and cats pray because they are not that smart, and they felt that all children do not pray either because they do not believe or because they do not know about the religion.

Prayer begins as just a word that is meaningless to the child. Over time it develops into a mental activity associated with a specific system of religious belief not shared by all people in the world. Another change is the shift from using prayer to gratify personal desires or to thanking God for things already received. Older children were noted to ask God for peace or to help the poor or the sick.

Affectively, young children associated prayer only with a fixed time, as in before going to bed, at church, or before eating. Older children used it to respond to specific feelings. For example, they may have been worried, upset, lonely, or troubled. Negative feelings elicited prayer more than positive ones. Younger children were often upset if these prayers were not answered while older ones were more resigned, also seeing God as a helper (Long, Elkind, and Spilka, 1967).

What do you think? Does prayer work for you?

9.6. Is There a Link Between Religion and Attachment?

Section Learning Objectives

- Define and describe parenting styles.

- Clarify the link between parenting styles and religion.

- Define and describe attachment styles.

- Clarify the link between attachment and religion.

9.6.1. Parenting Styles and Religion

9.6.1.1. Defining parenting style. Parenting styles are important because parents play a key role in the lives of their children. Children use them as attachment figures and learn about the world they live in through their tutelage. Darling and Steinberg (1993) defined parenting styles as all the attitudes, practices, and nonverbal expressions of the parents that characterize the nature of parent-child interactions in different situations. The authors’ further note that the effect of parenting styles is to alter the effectiveness of family socialization practices and, more importantly, the degree of receptiveness the child exhibits toward these practices.

9.6.1.2. Specific parenting styles. Contemporary research stems from the pioneering work of Diana Baumrind (1966). She cited the existence of three main parenting styles: authoritarian, authoritative, and permissive. Maccoby and Martin (1983) redefined this typology by identifying two underlying dimensions. The first is demandingness which is composed of control, supervision, and maturity demands. Next is responsiveness which reflects warmth, involvement, and acceptance. From these two dimensions a fourfold typology emerges. The discussion below of each parenting style will blend Baumrind’s (1966) and Maccoby and Martin’s (1983) research and add the fourth parenting style – uninvolved. .

First is the authoritarian parenting style which is characterized by a controlling, rigid, and cold parent. In this setting, the parent’s word is the law and he or she is willing to be punitive to enforce it. Strict, unquestioning obedience by their children is valued and an expression of disobedience is considered intolerable. These characteristics reflect high demandingness and low responsiveness (Maccoby & Martin, 1983). Baumrind (1966) adds that the authoritarian parent attempts to shape and control the child’s behavior to conform to a set standard of conduct which is usually absolute and theologically motivated and at times created by a higher authority. The child should also accept the parent’s word for what is right. Children of these types of parents tend to be withdrawn, unfriendly, and have relatively few social skills. Additionally, they behave uneasily around peers. Girls of authoritarian parents remain dependent on their parents while boys express hostility.

The second parenting style is the authoritative parenting style and these parents set firm, clear limits on their child’s behavior. Unlike the authoritarian parent, authoritative parents are willing to hear disagreement from the children and give reasons for their rules. If the child is punished, the parent states a rationale for the punishment that is imposed. These parents exhibit high demandingness and high responsiveness (Maccoby & Martin, 1983). Baumrind (1966) adds that the parent directs the child’s behavior in a rational, issue-oriented manner and that she recognizes that the child has her own interests and peculiarities. Children of these types of parents are encouraged to be independent and are often self-assertive and cooperative. They tend also to be friendly with their peers and possess a strong motivation to achieve.

The third parenting style is permissive or indulgent. These parents provide inconsistent and lax feedback. As such, they require little of their children and do not feel like they have much to do with how their children turn out (Feldman, 1997). Baumrind (1966) says that permissive parents make few demands for household responsibilities and they present themselves as a resource for the child to use as she wishes. These parents exhibit low demandingness and high responsiveness (Maccoby & Martin, 1983).

And finally, is the uninvolved or neglectful parenting style, characterized by being unusually uninvolved in the child’s life and shows no real concern for the well-being of the child. These parents exhibit low demandingness and low responsiveness (Maccoby & Martin, 1983). Their children are often moody and, like permissive-indulgent children, often have low self-esteem and low social skills, both of which have been linked to drug use, delinquency, and poor academic achievement (Radziszewska, Richardson, Dent, and Flay, 1996).

9.6.1.3. A parenting style and religious behavior link? Some early studies by researchers, such as Bateman and Jensen (1958), do indicate a potential link between parenting and religiosity. The authoritarian parenting style is similar to the Biblical injunctions to emphasize obedience among children. It warns parents not to spare the rod (Zern, 1987). This has also been noted by Fugate (1980) and Meier (1977) who said that those who adopt a literal belief in the Bible often utilize corporal punishment at both home and school. Nunn (1964) suggests that some parents use the image of a punishing God to control their children’s behavior. Nelson and Kroliczak (1984) attempted to replicate Nunn’s study using Minnesota Elementary Schools and obtained different results. They discovered like Nunn, that when parents did use this controlling image of a deity, children produced higher self-blame scores and a greater need to be obedient. But overall, parents do not generally use such coalitions with God to control a child’s behavior.

9.6.2. Attachment and Religion

9.6.2.1. Defining attachment and styles. Attachment is an emotional bond established between two individuals and involving one’s sense of security. Our attachment during infancy have repercussions on how we relate to others for the rest of our lives. Mary Ainsworth (1978) identified three attachment styles infants can possess. The first is a secure attachment and results in the use of a caretaker, often the mother, as a home base to explore the world. The child will occasionally return to her. The child also becomes upset when the caretaker leaves and goes to the mother when she returns. Next is the avoidantly attached child who does not seek closeness with her and avoids the mother after she returns. Finally, is the ambivalent attachment in which the child displays a mixture of positive and negative emotions toward the mother. She remains relatively close to her which limits how much she explores the world. If the mother leaves, the child will seek closeness with the mother all the while kicking and hitting her.

A fourth style has been added due to recent research. This is the disorganized-disoriented attachment style which is characterized by inconsistent, often contradictory behaviors, confusion, and dazed behavior (Main & Solomon, 1990). An example might be the child approaching the mother when she returns, but not making eye contact with her.

The interplay of a caregiver’s parenting style and the child’s subsequent attachment to this parent has long been considered a factor on the psychological health of the person throughout life. For instance, father’s psychological autonomy has been shown to lead to greater academic performance and fewer signs of depression in 4th graders (Mattanah, 2001). Attachment is also important when the child is leaving home for the first time to go to college. Mattanah, Hancock, and Brand (2004) showed in a sample of four hundred four students at a university in the Northeastern United States that separation individuation mediated the link between secure attachment and college adjustment. The nature of adult romantic relationships has been associated with attachment style in infancy (Kirkpatrick, 1997). One final way this appears in adulthood is through a person’s relationship with a god figure.

9.6.2.2. Attachment and religion. An extrapolation of attachment research is that we can perceive God’s love for the individual in terms of a mother’s love for her child, but this attachment is not always to God. For instance, Protestants, seeing God as distant, use Jesus to form an attachment relationship while Catholics utilize Mary as their ideal attachment figure. It could be that negative emotions and insecurity in relation to God do not always signify the lack of an attachment relationship, but maybe a different type of pattern or style (Kirkpatrick, 1995). Consider that an abused child still develops an attachment to an abusive mother or father. The same could occur with God and may well explain why images of vindictive and frightening gods have survived through human history.

One important thing to note is that in human relationships, the other person’s actions can affect the relationship, for better or worse. Perceived relationships with God do not have this quality. As God cannot affect us, we cannot affect Him. This allows the person to invent or reinvent the relationship with God in secure terms without allowing counterproductive behaviors to retard progress. Hence, Kirkpatrick (1995) says people “with insecure attachment histories might be able to find in God…the kind of secure attachment relationship they never had in human interpersonal relationships (p. 62).” The best human attachment figures are ultimately fallible while God is not limited by this.

Pargament (1997) defined three styles of attachment to God. First is the ‘secure’ attachment in which God is viewed as warm, receptive, supportive, and protective, and the person is very satisfied with the relationship. Next is the ‘avoidant attachment’ in which God is seen as impersonal, distant, and disinterested, and the person characterizes the relationship as one in which God does not care about him or her. Finally, is the ‘anxious/ambivalent’ attachment. Here, God seems to be inconsistent in his reaction to the person, sometimes warm and receptive and sometimes not. The person is not sure if God loves him or not. We might say that the God of the secure attachment is the authoritative parent, the God of the avoidant attachment is authoritarian, and the God of the anxious/ambivalent attachment is permissive.

Kirkpatrick and Shaver (1990) note that attachment and religion may be linked in important ways. They offer a “compensation hypothesis” which states that insecurely attached individuals are motivated to compensate for the absence of this secure relationship by believing in a loving God. Their study evaluated the self-reports of 213 respondents (180 females and 33 males) and found that the avoidant parent-child attachment relationship yielded greater levels of adult religiousness while those with secure attachment had lower scores. The avoidant respondents were also four times as likely to have experienced a sudden religious conversion.

They also remind the reader that the child uses the attachment figure as a haven and secure base and go on to note that there is ample evidence to suggest the same function for God. Bereaved persons become more religious, soldiers pray in foxholes, and many who are in emotional distress turn to God. Further, Christianity has a plethora of references to God being by one’s side always and the person having a friend in Jesus.

Pargament (1997) expanded upon the compensation hypothesis and showed that the relationship between attachment history and religious beliefs is far from simple. He summarized four relationships between parental and religious attachments extrapolated from Kirkpatrick’s research. First, if a child had a secure attachment to the parent, he may develop a secure attachment to religion, called ‘positive correspondence.’ In this scenario, the result of a loving and trusting relationship with one’s parents is transferred to God as well. This is contrary to the findings of Kirkpatrick and Shaver (1990) which said that securely attached individuals displayed lower levels of religiosity. More in line with their view is Pargament’s second category, secure attachment to parent and insecure attachment to religion, called ‘religious alienation.’ Here the person who had a secure attachment to parents may not feel the need to believe in God. He does not need to compensate for any deficiencies.

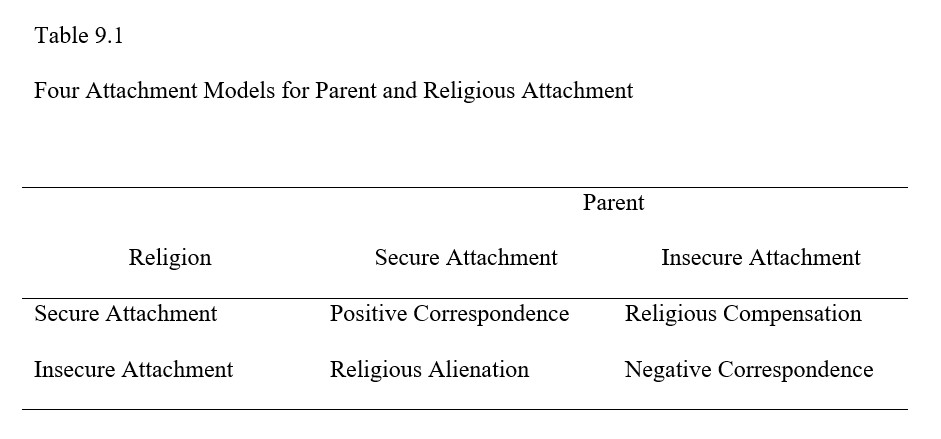

The third category is also in line with Kirkpatrick and Shaver’s study. Modeled after their hypothesis, ‘religious compensation’ results from an insecure attachment to parent and a secure attachment to religion. Finally, an insecure attachment to parents may yield an insecure attachment to religion called ‘negative correspondence’ (see Table 9.1). These insecure parental ties have left the person unequipped to build neither strong adult attachments nor a secure spiritual relationship. The person may cling to “false gods” like drug and alcohol addiction, food addiction, religious dogmatism, a religious cult, or a codependent relationship.

9.7. Religion and Death

Section Learning Objectives

- Clarify to what extent Americans believe in an afterlife.

- Define and describe terror management theory.

- Describe a typical MS study.

- Examine the link between TMT and worldview defense.

- Examine the link between TMT and self-esteem.

- Examine the link between TMT and in-group bias.

- Examine the link between TMT and prosocial behavior.

- Examine the link between TMT and religion.

- Describe the salient features of an NDE.

- Appraise the research on NDEs.

9.7.1. Belief in the Afterlife

So, what happens when we die? And the answer is…… we really don’t know. Religions speculate as to what happens when we die in terms of our soul and not really the physical body and for many, this tenet of the faith is very strongly held onto. On June 15, 2015, The Huffington Post published an article called Paradise Polled: Americans and the Afterlife in which author Kathleen Weldon reported that American’s belief in an afterlife has remained relatively steady since 1944. She reports the results of a 2014 CBS News poll showing that 66% of respondents believed in heaven and hell, 11% in just heaven, and 17% in neither. It is no surprise that 36% of atheists and agnostics report believing in heaven and hell and 7% in heaven only.

With a belief in heaven (and hell) firmly established in the U.S., the next question is who is able to enter heaven. The results are interesting. A 2006 poll showed that 69% of respondents said Christians and non-Christians can go to Heaven, with 24% saying only Christians. Another poll that year asked if a person not of one’s faith could go to heaven and attain salvation and found that 84% of those polled said these people could. Only 9% said no.

So, the question now turns to what people do about the anxiety a fear of one’s death causes. Terror Management Theory provides us a potential answer.

Check out the Huffington Post article by visiting:

https://www.huffingtonpost.com/kathleen-weldon/paradise-polled-americans_b_7587538.html

9.7.2. Managing Death Anxiety – Terror Management Theory (TMT)

9.7.2.1. What is TMT? Ernest Becker (1962, 1973, & 1975) stated that it is the human capacity for intelligence, to be able to make decisions, think creatively, and infer cause and effect, that leads us to an awareness that we will someday die. This awareness manifests itself as terror and any cultural worldviews that are created need to provide ways to deal with this terror, create concepts and structures to understand our world, answer cosmological questions, and give us a sense of meaning in the world.

Based on this notion, Terror Management Theory (TMT; Greenberg, Pyszczynski, and Solomon, 1986) posits that worldviews serve as a buffer against the anxiety we experience from knowing we will die someday. This cultural anxiety buffer has two main parts. First, we must have faith in our worldviews and be willing to defend them. Second, we derive self-esteem from living up to these worldviews and behaving in culturally approved ways. Culture supports a belief in a just world and meeting the standards of value of the culture provides us with immortality in one of two ways. Literal immortality is arrived at via religious concepts such as the soul and the afterlife. Symbolic immortality is provided by linking our identity to something higher such as the nation or corporation and by leaving something behind such as children or cultural valued products. It has also been linked to the appeal of fame (Greenberg, Kosloff, Solomon, Cohen, and Landau, 2010).

Finally, based on whether death thoughts are in focal attention or are unconscious, we employ either proximal or distal defenses. Proximal defenses involve the suppression of death-related thoughts, a denial of one’s vulnerability, or participating in behavior that will reduce the threat of demise (i.e., exercise) and occur when thought of death is in focal attention. On the other hand, distal defenses are called upon when death thoughts are unconscious and involve strivings for self-esteem and faith in one’s worldview and assuage these unconscious mortality concerns through the symbolic protection that a sense of meaning offers.

9.7.2.2. The typical mortality salience study. In a typical MS study, participants are told they are to take part in an investigation of the relationship between personality traits and interpersonal judgments. They complete a few standardized personality assessments which are filler items to sustain the cover story. Embedded in the personality assessments is a projective personality test which consists of two open ended questions which vary based on which condition the participant is in. Participants in the MS condition are asked to write about what they think will happen to them when they die and the emotions that the thought of their own death arouses in them. Individuals in the control condition are asked to write about concerns such as eating a meal, watching television, experiencing dental pain, or taking an exam. Next, they complete a self-report measure of affect, typically the PANAS, to determine the effect of MS manipulation on their mood. Finally, they are asked to make judgments about individuals who either directly or indirectly threaten or bolster their cultural worldviews.

9.7.2.3. Worldview defense. General findings on TMT have shown that when mortality is made salient, we generally display unfavorable attitudes toward those who threaten our worldview and celebrate those who uphold our view. This effect has been demonstrated in relation to anxious individuals even when part of one’s in-group (Martens, Greenberg, Schimel, Kosloff, and Weise, 2010) such that mortality reminders led participants to react more negatively toward an anxious police liaison from their community (Study 1) or to a fellow university student who was anxious (Study 2). Mortality salience has also been found to elevate preference for political candidates who are charismatic and espouse the same values associated with the participant’s political worldview, whether conservative or liberal (Kosloff, Greenberg, Weise, and Solomon, 2010).

Rosenblatt, Greenberg, Solomon, Pyszczynski, and Lyon (1989) examined reactions of participants to those who violated or upheld cultural worldviews across a series of six experiments. In general, they hypothesized that when people are reminded of their own mortality, they are motivated to maintain their cultural anxiety buffer; they are punitive toward those who violate it and benevolent to those who uphold it. Experiments 1 and 3 provided support for the hypothesis in that subjects induced to think about their own mortality increased their desire to punish the moral transgressor (i.e., to recommend higher bonds for an accused prostitute) while rewarding the hero (Experiment 3). Experiment 2 replicated the findings of Experiment 1 and extended them by showing that increasing MS does not lead subjects to derogate just any target as it had no effect on evaluations of the experimenter. Also, MS increased punishment of the transgressor only among subjects who believed the target’s behavior was truly immoral.

Experiments 4 – 6 tested alternative explanations for the findings. First, self-awareness could lead individuals to behave in a manner consistent with their attitudes and standards. The results of Study 4 showed that unlike MS, self-awareness does not encourage harsher bond recommendations and in fact, heightened self-awareness reduces how harshly a prostitute is treated among individuals with positive attitudes toward prostitution. In Study 5, physiological arousal was monitored, and MS was found not to arise from mere heightened arousal. Finally, Experiment 6 showed that features of the open-ended death questionnaire did not lead to the findings of Studies 1-5, but rather to requiring subjects to think about their own deaths.

McGregor, Lieberman, Greenberg, Solomon, Arndt, Simon, and Pyszcznski (1998) tested the hypothesis that MS increases aggression against those who threaten one’s worldview by measuring the amount of hot sauce allocated to the author of a derogatory essay. In the study, politically conservative and liberal participants were asked to think about their own death (MS) or their next important exam (control). They were then asked to read an essay that was derogatory toward either conservatives or liberals. Finally, participants allocated a quantity of very spicy hot sauce to the author of the essay, knowing that the author did not like spicy foods and would have to consume the entire sample of hot sauce. As expected, MS participants allocated significantly more hot sauce to the author of the worldview-threatening essay than did control participants.

In a second study, participants thought about their own mortality or dental pain and were given an opportunity to aggress against someone who threatened their worldview. Half of the MS participants allocated the hot sauce before evaluating the target while the other half evaluated the target before allocating the hot sauce. Results of Study 2 showed that MS participants allocated significantly more hot sauce when they were not able to verbally derogate the targets prior to the administration of hot sauce. However, when MS participants were able to first express their attitudes toward the target, the amount of hot sauce allocated was not significantly greater than for the controls. This finding suggests that people will choose the first mode of worldview defense provided to them.

9.7.2.4. Self-esteem. According to the anxiety buffer hypothesis, if a psychological structure provides protection against anxiety, then strengthening that structure should make an individual less prone to displays of anxiety or anxiety related behavior in response to threats while weakening that structure should make a person more prone to exhibit anxiety or anxiety related behavior in response to threats. In support of this, Greenberg et al. (1992) showed that by increasing self-esteem, self-reported anxiety in response to death images and physiological arousal in response to the threat of pain could be reduced. Furthermore, the authors found no evidence that this effect was mediated by positive affect. Additional support for the function of self-esteem in reducing anxiety was provided by Harmon-Jones, Simon, Greenberg, Pyszcynski, Solomon, and McGregor (1997), who showed that individuals with high self-esteem, whether induced experimentally (Experiment 1) or dispositionally (Experiment 2), did not respond to MS with increased worldview defense and that this occurred due to the suppression of death constructs (Experiment 3).

9.7.2.5. TMT and in-group bias. Recall that Rosenblatt et al. (1989) found that when mortality is salient, we have a tendency to derogate those who attack our worldview (Study 1) and that this effect does not generalize to just anyone (Study 2) as the experimenter was not viewed negatively. Also, when mortality is salient, those who defend our worldview are seen as a hero. Likewise, Greenberg, Pyszczynski , Solomon, Rosenblatt , Veeder, Kirkland, and Lyon (1990) demonstrated that under MS, we have a tendency to derogate an out-group member (Jewish person) compared to an in-group member (Christian). This tendency to derogate occurs even if we are presented with information concerning their credibility and background. Interestingly, the effects of MS in relation to out-group member evaluation can be reversed if we prime a tolerance norm (Greenberg, Simon, Pyszczynski, Solomon, and Chatel, 1992).