Module 1: Introducing Motivation

Module Overview

Welcome to this book on motivation. As with any textbook, our starting point in Module 1 will be to define terms and establish a foundation for what motivation is. To this end, we will define motivation but also what it means to be unmotivated. Though the latter may seem trivial and unneeded right now, you will soon see just how important it is as it dispels a common misconception. We will discuss internal and external sources of motivated behavior and then examine how time motivates us. No book would be complete without at least some discussion of the history of the subfield and for our purposes, a presentation of some of the organizing theories in the study of motivation. Evolution is a crucial topic in the field of psychology and will be discussed briefly in this module, and then much more throughout the book. Finally, we must discuss research methods in the subfield of motivation. If you had this in your introductory psychology class, you will be good. There is nothing new to add but it is critical to make sure you remember key research designs and how we employ the scientific method. These will come up numerous times throughout the next 15 modules. I hope you enjoy this book and the first module. If you have questions, please let your instructor know.

Module Outline

- 1.1. What Does It Mean to be Motivated?

- 1.2. Sources of Motivated Behavior

- 1.3. Motivation as a Function of Time

- 1.4. Theories/History of Motivation

- 1.5. Understanding Motivation through Evolution

- 1.6. Researching Motivation

Module Learning Outcomes

- Define motivation and clarify what it means to be unmotivated.

- Differentiate what is meant by the push and pull of motivated behavior.

- Clarify how behavior is motivated by the past, present, and future.

- Discuss the historical context of the exploration of motivation.

- Identify and describe key theories about motivated behavior.

- Clarify evolutionary roots of motivated behavior.

- List and describe key research designs used in psychology and clarify how we employ the scientific method.

1.1. What Does it Mean to be Motivated?

Section Learning Objectives

- Define motivation.

- List the dimensions of behavior.

- Define instrumental behavior and clarify the role of motives and incentives.

- Clarify how the term unmotivated is misused in our society.

- List and define the two types of energy needed for motivated behavior.

- Describe through exemplification, the role played by knowledge and competence in successfully completing motivated behavior.

As you begin to read this book and understand how psychologists study motivation, I would bet you already are pretty familiar with the concept. The fact that you are a student taking a college class, registered at a college or university, and pursuing a bachelor’s degree (major not important) shows that you are a motivated individual. Congratulations. You have a goal in mind, are driven to achieve it, are committed to the cause, have what is necessary to accomplish this endeavor or are willing to learn those skills, and are looking to a better future for yourself and family. This is the essence of motivation, but what exactly does it mean?

The term motivation comes from the Latin, movere, meaning to be moved. In terms of a definition, motivation is defined as being moved into action or engaging in behavior directed to some end. The behavior we engage in can be described by specific dimensions. First, maybe our goal is to engage in a motivated behavior more than once. This is called frequency. Or maybe we want to engage in it for a longer period of time. If that is your purpose, you are focused on duration. Finally, we might already engage in the behavior often and long enough, but want to go at it harder. In this case, we are focused on intensity. A runner may want to run more days a week, for increasingly longer periods of time so as to be able to compete in a marathon, or run a mile in less time. This describes frequency, duration, and intensity, respectively. Behavior directed in this way is said to be instrumental or done with the intent to fulfill a person’s motive. But what’s a motive? We hear this term a lot in terms of legal issues. Atkinson (1983) and McClelland (1987) state that a motive is an individual’s natural proclivity to approach things that are positive while avoiding those that are negative. These things are called incentives and are any reward or aversive stimulus that we come to expect in our environment. If we study hard for our exam, we expect an A. If we do not pay our taxes on time, we should anticipate a nasty letter or visit from the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), plus a stiff monetary penalty.

People often talk about being unmotivated. What does it mean to be unmotivated then? Can we truly be unmotivated? Simply being unmotivated means we are motivated to another end and does not imply an absence of motivation. Can you ever really be unmotivated then? If, upon arriving at home after a long day of classes, you lay down on your bed instead of making dinner or doing schoolwork, are you unmotivated? No. Though you may not be engaging in the preferable behavior of finishing a paper due in class tomorrow, you are instead engaging in the behavior of getting rest. So, you are not motivated for one end, but for another. Still, you are motivated.

No matter what the behavior is that we wish to engage in and whatever dimension we are concerned about, we need to have certain resources to complete it. These resources include energy, knowledge, and competence. First, in terms of energy, we need both physical and psychological energy. Physical energy includes having the glucose necessary to sustain the activity. Think about the dimensions. Working out for 20 minutes requires less energy expenditure (glucose) than does working out for 30 or 45 minutes. Also, if you are running harder today than you did yesterday (say, yesterday you ran at 5mph but today are pushing 5.2mph) you will need more energy to do so. Keep in mind that not only do your legs need energy to function, so does your brain. So, we need psychological energy which might also be called self-regulation or adaptation energy (more on this later). If we are stressed out by having to write a major paper in a class, or do an oral presentation, we will need energy to help us better cope and adapt to the situation. If we are in public and upset by an idea another individual is espousing, we may need to bite our tongue so as not to say something potentially offensive to others. As a rule of thumb, we might say that the amount of self-regulation needed is a function of how strongly we hold our own attitude.

But is energy enough? Let’s say we have sufficient amount of both types. Does that mean we are guaranteed success when we engage in our motivated behavior? Not necessarily. To lose weight, we have to also know how to lose weight. As anyone who has embarked upon this most difficult goal can tell you, weight loss is more than just eating less or working out more. You need to do both, but also manage your stress and get sufficient sleep. This is a bit of an oversimplification of the process of weight loss, but the point is that without knowing that all four behaviors factor into weight loss, your chances of success are not as high as they could be. So, knowledge is key.

But maybe you know what you need to, such as having the knowledge of how to train for a marathon and you possess both types of energy in sufficient quantities. Are you competent to complete the task? It may be that you have a bad knee or feet that will not sustain hours of continual pounding. I tried to train for a marathon about 15 years ago. I had the dedication (psychological energy), proper nutrition (physical energy), and a great plan to slowly build up to the long distance (knowledge), but my plantar fasciitis flared up and made running for a long time impossible (no competence).

KEY POINT – You need all four resources for motivated behavior to be successful. We will discuss all this, and more, throughout the book.

1.2. Sources of Motivated Behavior

Section Learning Objectives

- Contrast the push and pull of motivation.

- Describe push motivation in terms of needs, the drive reduction model, and motivated behavior.

- Describe pull motivation in terms of incentives.

- Clarify how some motivated behavior that we engage in is actually a product of both push and pull (or just one or the other).

1.2.1. Defining Terms

When we talk about motivation, we also talk about the push and the pull of motivation. To what do these terms refer? First, push arises from within or is an internal source of motivated behavior. Have you ever used the expression ‘I need to push myself to do something?’ If so, you are already familiar with the phrase. Second, pull arises from outside of us. Think about the act of pulling. Can you pull yourself? No. Someone else needs to do the pulling and so if you keep that in mind you will recognize pull as coming from outside. Let’s explore each now.

1.2.2. The Push of Motivated Behavior

Think of the push of motivation like this:

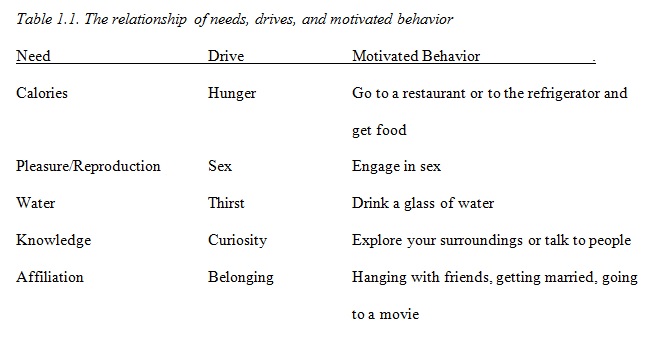

Need –> Drive –> Motivated Behavior

Some deficiency, or need, arises in our body which has to be dealt with. This creates a state of tension which we want to resolve since it is uncomfortable (the drive). We engage in motivated behavior and if successful, the need is replenished and the tension/drive ends. Let’s look at each of these components closer.

1.2.2.1. Needs. Again, needs are a deficiency in some resource important to the organism. Needs can be divided into two main types: 1) physical/biological including nutrients/food, water, air, temperature, and sex and 2) psychological including affiliation, competence, achievement, power, and closure.

Maslow (1970) presented needs in the form of a pyramid in which lower-level needs had to be satisfied before upper-level ones could be. He called it his hierarchy of needs. At the bottom of the pyramid are the physiological needs such as food, water, temperature, oxygen, and sex. Above this are safety and security needs which focus on protection from the elements, being secure in our income, having order and law in society, and stability. Next are love and belongingness needs which focus on feeling socially connected to others and being involved in mature relationships. Esteem needs are the next highest and focus on how we feel about ourselves, gaining mastery, independence, prestige, and responsibility. Finally, is self-actualization which is when we realize our potential, feel fulfilled, seek personal growth, and pursue interests out of intrinsic pleasure and not for extrinsic reasons (more on this in a bit). As you work from bottom to top, a person satisfies these needs less and less and self-actualization needs are rarely satisfied. Critics point out that the model cannot explain all human actions such as starving oneself to call attention to social issues and that contrary to what Maslow said, you do not necessarily have to satisfy a lower need before a higher one. As college students, I bet most of you feel pretty good with your esteem needs, and maybe for the online student who typically is older and has a family and spouse, love and belongingness. But what about physiological? Early in the semester you might be good but how are things going with eating healthy, sleeping 8 hours, reducing stress, etc. right before finals? Likely not good, meaning that you might have satisfied your esteem needs (third level) but not your physiological needs (first level). Does your pyramid of needs crumble due to this? Could you be satisfying needs at more than one level, and at the same time? Think about this before moving on.

1.2.2.2. Drives. Once a resource has been registered as deficient by the hypothalamus of the central nervous system, a state of tension or uneasiness occurs, called a drive. No one likes the feeling and so the body is motivated to do something about it, or to reduce the drive, called the drive reduction model. How do you feel when hungry or thirsty? What if you are having difficulty achieving your goals? Essentially, the essence of this model is to return the body to homeostasis, or a state of equilibrium or balance. Think of the body as a thermostat, much like the one in your apartment or dorm room. Let’s say you set the thermostat to 69 degrees. This is the desired state. The thermostat will then measure the temperature in the apartment, called the actual state. The two states are compared to one another. If the same, no additional action is needed. But what if your house is 73 degrees? The thermostat will trigger actions to lower the temperature. If the actual state is less than the desired state (i.e., your house is 65 degrees), actions will be taken to raise the temperature. In either case, information is fed back to the thermostat (or your brain) letting it know when the discrepancy is 0 or there is no difference between actual and desired states. Once this occurs, all actions taken to deal with the deficiency are ceased and the body is at equilibrium. This is called the negative feedback loop.

Exactly the same thing occurs in your body, and we can use temperature as a comparison. If you are warmer than your body prefers, your brain will trigger actions to lower your body temperature such as sweating. If you are colder, your body may trigger shivering. We will deal with this in more detail in Module 14.

1.2.2.3. Motivated behavior. Our discussion began with needs or deficiencies we are experiencing which cause drives or states of discomfort. Our last piece of the puzzle is motivated behavior or any behavior we engage in to reduce the drive. In our example of body temperature, the brain itself can take action to lower or raise the temperature. We can engage in behaviors as well, such as drinking hot chocolate or putting on another layer of clothes to raise our body temperature; or to taking off clothes, drinking something cold, or turning on a fan to lower the temperature. Examine Table 1.1. for other examples of how motivated behavior is used to reduce drives and restore our resources to a state of balance, or equilibrium.

1.2.3. The Pull of Motivated Behavior

What are some ways pull appears in our world? Well, when we think of pull, we usually think of incentives and most are regarded as good things. Our employer might give gift cards to local restaurants for sales reps who outsell their fellow employees. Our parents may tell us that for each ‘A’ we earn this semester, we will receive a bonus of $50.00. Our insurance company grants us discounts for safe driving.

1.2.4. The Interaction of Push-Pull

When it comes down to what motivates behavior, the source may be a combination of internal (push) AND external (pull), or just simply internal OR external. Consider that when it comes to jobs, some people work in their career fields because they truly enjoy what they do (the motive). We call this intrinsic motivation and later when we discuss psychological needs in Module 8, we might say the person has a high achievement need. Others work simply for the paycheck and prestige their job offers (incentives) and we call this extrinsic motivation. Others may obtain genuine pleasure from their job but also enjoy the large paycheck every two weeks. We are all influenced by either push (intrinsic motivation), pull (extrinsic motivation) or a combination of the two.

1.3. Motivation as a Function of Time

Section Learning Objectives

- Describe how we are motivated by the past.

- Describe how we are motivated by the present.

- Describe how we are motivated by the future.

1.3.1. When We Are Motivated by the Past

The past is of particular interest to psychologists because through one’s personal history, or the history of their own life, we can come to understand why a person is engaging in the behavior they are today (i.e., the present). For instance, an industrial/organizational psychologist may want to know why an employee’s productivity has gone down recently. The psychologist might learn that the employee was passed over for a promotion that on paper, they were more than qualified for. Due to this, the employee now does not see much point in exerting extra effort and basically is working for a paycheck and nothing more. The individual may even be seeking other employment. In the case of a social psychologist, an explanation for prejudicial ideas or discriminatory behavior of an individual (or group) would be sought out. Maybe the individual experienced institutional racism years ago which has left them jaded. Or what if a riot breaks out? What might explain the mob behavior exhibited by numerous individuals? In the case of behavior modification, an applied behavior analyst might try to find the right reinforcer to use to bring about behavior change. Looking at the personal history of the client can help identify what has worked in the past to influence a treatment plan now, ultimately leading to positive change in the future. Keep in mind, that what works for one person, may not work for another. Just because Jim likes video games and is motivated to complete his homework on time to have extra time to play Call of Duty, does not mean that Kyland will be motivated in the same way. Upon closer inspection, we might find that Alec favors racing games and shooters have no effect on his behavior. Both Alec and Kyland are motivated in much different ways by how the incentive of video games is presented to them, demonstrating individual differences. Finally, a developmental psychologist may want to understand the romantic attachment patterns of a 24-year-old man by looking at his relationship with his parents throughout childhood. There are numerous other examples we will explore beginning in Module 9, but this gives you a general sense of how our personal history can affect our motivated behavior.

Please note that our evolutionary history is another way we are motivated by the past and will be discussed in Section 1.5. For now, evolutionary history refers to the shared history of a species and understanding why we act the way we do now. This history can go back thousands of years and differs from one’s personal history, which is a much shorter period based on the average human life span. The school of thought in psychology called Functionalism, which was active in the late 1800s and early 1900s and exists today in the form of applied psychology, asserted that any behavior that is present today exists because it serves an evolutionary advantage to the organism. Think about some behaviors made by most human beings. How might they lead to the survival of the species?

1.3.2. When We Are Motivated by the Present

There are numerous examples I could give for how we are motivated in the here and now, called the present, but will focus on choices, goals, and escape behavior. Throughout the rest of this book, we will encounter other examples so be on the lookout for them.

Choices. Life is all about them. Just take a walk down the toilet paper aisle. First, you have to decide between name brand or off brand. Next, extra soft or extra strong. Then there is the size of the roll – regular, double, mega, etc. This can be quite confusing for some but in reality, whatever package you purchase, its use will be the same (no need to describe this anymore, right? J). All of these options are competing with one another making the choice more difficult.

Goals are another way we are motivated in the present. Now we may have a long-term goal of earning our Bachelor’s degree which is set in the future, whether near or far depending on where you are in your academic career, but we also have short term goals which may include finishing a paper due this week, studying for an exam, participating in philanthropy for our sorority or fraternity, etc. Related to choice, we may have to decide how to expend our physical and psychological energy on these short term goals since we have a limited amount of both and cannot possibly do everything at once. Students sometimes have to make tough decisions about where to expend energy when preparing for multiple exams. You might be struggling in statistics but acing social psychology and so if both classes have an exam that week you may need to invest more time in studying for the statistics exam and less for social psychology. Yes, you could take a lower grade than you would prefer in social psychology but since you are performing well already, you can afford to lose a few points, and the extra time invested in statistics earns you a much-needed higher grade. This type of strategizing ultimately leads to successfully completing your short-term goals of passing the two exams and both classes, and your long-term goal of earning a degree in psychology.

Escape behavior is a final example of how we are motivated in the present. After some period having not ingested, inhaled, or injected a drug, we begin to display withdrawal symptoms. To escape this most unpleasant state in the now, we take in more of the drug. The symptoms go away, reinforcing the behavior of additional or continued drug use when withdrawal symptoms occur. Consider if you are a coffee drinker. What withdrawal symptoms do you experience when you do not have enough caffeine in your system? What do you do about this?

1.3.3. When We Are Motivated by the Future

A stimulus in our environment presents itself such as seeing our significant other. We engage in the behavior of saying we love them, to which they reply they love us too. This makes us feel good and so in the future we say we love them when we see them again. This simple transaction occurs time and time again throughout our lives and in relation to our significant other, parents, siblings, close friends, etc. and represents an anticipation of future behavior because of the favorable consequences of a past action.

Let’s go back to our example for drug addiction. As noted, we can escape the ugly withdrawal symptoms by taking in more drug now. What we learn is that in the future, we can avoid these symptoms by simply taking more of the drug, called avoidance behavior in learning theory.

How might our emotions be affected by the anticipation of the future? Affective forecasting anticipates how we will feel in the future when a similar situation arises or we complete our goal. In your darkest moments as a student, pause and envision what graduation will be like. How will you feel with your parents, friends, siblings, etc. cheering you on as your name is called and you walk across the stage? Most likely you will feel elation, pride, excitement, and maybe even concern about what you will do with your degree (if you do not have a job now). You are making a prediction about what this event will be like similar to weather forecasters who make predictions about what the weather will be like for the upcoming week. Maybe comparing this to a weather forecast is not the best analogy I could make, considering that weather forecasters are often mistaken in their prediction. But guess what, so are we. As Wilson and Gilbert (2005) point out, our mispredictions can take several forms. First, we make the impact bias in which we overestimate how long or how intense our reaction to a future event will be. This can lead to focalism or overestimating to what extent we will think about the event in the future and to underestimate how other events will affect our thoughts and feelings. Another outcome of the impact bias is not recognizing how readily we might make sense of a novel or unexpected event.

Second, Wilson and Gilbert (2005) say that we experience immune neglect or failing to realize the role that defenses such as dissonance reduction, self-serving attributions, positive illusions, etc., play in recovering from negative emotional events when we attempt to predict our future emotional reactions. Consequences of this might include rationalizing a decision when it is difficult to reverse, such as in making a major purchase or making economically illogical decisions due to our tendency to weight losses greater than gains. Keep this in mind as we will return to a discussion of bias, heuristics, and losses looming larger than gains later in this book.

1.4. Theories/History of Motivation

Section Learning Objectives

- Define philosophy and list and describe its four branches.

- Discuss how Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle described motivation.

- Clarify how the Greeks tackled the issue of what is happiness.

- Discuss how Hobbes and Bentham interpreted human motivation.

- Describe the arousal theory of motivation.

- Describe the incentive theory of motivation.

- Describe the cognitive theory of motivation.

- Describe the drive-reduction theory of motivation.

- Describe the instinct theory of motivation.

1.4.1. Motivation and Philosophy

Though psychology was not established as a formal field until the mid to late 1870s by Wilhelm Wundt, when he established the first psychological laboratory in Leipzig, Germany, people all throughout time have asked questions in relation to psychological topics. One might speculate that early cave women wondered why cavemen kept clubbing them on the head and dragging them to their caves. Kidding…or not.

Let’s discuss philosophy briefly since psychology as a social science arose from it (and physiology, too, but that is another discussion for a much different class). Philosophy can be defined as the love and pursuit of knowledge and has four major areas: metaphysics, epistemology, logic, and ethics. First, metaphysics studies the nature of reality, what exists in the world, what it is like, and how it is ordered. This might not seem like much, but this area is the largest of the four and these topics are fairly heavy in nature. It poses such questions as ‘Is there a God?,’ ‘Do we have free will?,’ ‘What is a person?,’ and ‘How does one event cause another?.’ In terms of a link to psychology, psychologists attempt to understand people and how their mind works and why they did what they did. We also look for universal patterns, or cause and effect relationships which allow us to make predictions about the future. Finally, we might say we investigate the fate vs. free will issue by looking at whether everything we are going to be as a person is determined in childhood or can we change later in life.

So, what about epistemology, defined as the study of knowledge? Key questions philosophers ask concern what knowledge is and how do we know what we know. In terms of psychology, we study learning, knowledge as a cognitive process focusing on elements of knowledge (concepts, propositions, schemas, and mental images), and subconscious and nonconscious thinking.

Third is logic which focuses on the structure and nature of arguments. Philosophers investigate what constitutes good or bad reasoning while psychologists study formal and informal reasoning, heuristics and biases, and decision making.

Finally, ethics is the study of what we ought to do or what is best to do. Philosophers ask questions centered on what is good, what is right, how should I treat others, and what makes actions or people good. Similarly, psychologists study moral development, the issue of the improper or proper use of punishment, and obedience, all of which will be topics in later modules of this book.

This discussion, though brief, is a very important one to have undertaken. Again, given that psychology arose out of philosophy it should not seem odd to you that we tackle the same issues and, in some ways, many of the same questions, but with different methods in mind. More on methods later in this module. For now, know that many of the links mentioned above will be addressed in this textbook, though we cannot cover every link possible. This book will give you a survey of how psychologists study motivation proper, basically the focus of Modules 1-8, and then a more focused examination at different subfields of psychology in Modules 9-14.

Let’s talk about a few key philosophers and their thoughts on motivation and the types of motivated behavior we might engage in. Our discussion will start with the Greeks and the big three – Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle. In terms of what the goal of life is, Socrates (469-399 B.C.) said that people should focus on obtaining knowledge and then using it to act morally. But they do not always do this. Sometimes, they act immorally when they clearly know what is right. Socrates suggested this was due to the individual weighing the perceived benefits of doing wrong and finding that they were greater than the costs. In a nutshell, Socrates was interested in what it meant to be human and problems linked to human existence.

Plato (c. 428-347 B.C.) was a student of Socrates and spent much of his career sharing and expanding the ideas of his mentor. He wrote 36 dialogues and in his most famous, Republic, tackles the issue of the soul of a nation and the individual and proposes a three-part hierarchy between reason, emotion, and desire. Aristotle said that reason reigns supreme in the individual and a wise ruler should govern in the same way. It is through wisdom that we can see the true nature of things. He also is known for the Allegory of the Cave in which a prisoner escapes from his captivity in a cave to be blinded by the light of the sun as he exits. The sun represents truth in this allegory. Throughout his various writings, Plato also discussed the nature of the soul and sleep and dreams.

Finally, Aristotle (384-322 B.C.) said that information about our world comes from our five senses and that we could trust them to provide an accurate representation of the world. He proposed the laws of association to include the law of contiguity or thinking of one thing and then thinking of things that go along with it, law of similarity or thinking of one thing and then things similar to it, and law of frequency which says the more often we experience things together the more likely we will be to make an association between them. He wrote treatises on the nature of matter and change; existence; human flourishing on individual, familial, and societal levels; what makes for a convincing argument; and even discussed emotions, motivation, happiness, imagination, and dreaming too.

For more on the Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, check out:

Psychologists, as you will come to see later in this book, are concerned with the pursuit of happiness and philosophy is no different. Several schools of thought arose from Ancient Greece to deal with this. Most notable is Epicureanism which was developed by Epicurus, circa 306 B.C. He defined pleasure as the absence of pain in the body and trouble in the soul and said happiness was found by avoiding strong passions, living simply, and not depending on others. For Epicurus, the purpose of ethics was to identify an end and the means with which to achieve it. The chief end is pleasure.

Cynicism means to live as naturally as possible; reject worldly conventions such as money, fame, and power; and avoid too much pleasure. Human flourishing relied on being self-sufficient for the cynic and they felt that social conventions hindered the good life by establishing a code of conduct opposite to nature and reason and compromised freedom. To live in accord with nature, be self-sufficient, and to be free of convention, the cynic promoted askēsis, or practice, which led them to embrace hardship, live in poverty, and speak freely about how others lived.

Finally, Stoicism, developed by ancient Greek philosopher, Zeno of Citium around 300 B.C., took a deterministic stance and said that we were in control of our mental world and so feelings of unhappiness were our fault. Stoics said we should not be too positive either, as it can lead to over-evaluation of things and people and can lead to unhappiness should they be lost. The stoic says people should practice four cardinal virtues to include courage, justice, wisdom, and temperance. Their primary maxim was to ‘Live according to nature.’

Moving past the Greeks, we will discuss a few other philosophers. Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) said that people are inherently greedy, selfish, and aggressive and need a monarch to impose law and order for without it, Hobbes said life would be short lived, solitary, and overall not pleasant, or what he calls the “natural condition of mankind.” It is this fear of death that motivates people to make a social contract with a sovereign authority to decide what laws and moral code is best for all. For more on Hobbes and his ideas, please read The Leviathan or check out this site: http://www.iep.utm.edu/hobmoral/#H5.

Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) is best known for his principle of utilitarianism. He said human behavior can be explained through two primary motives – pleasure and pain – which determine what we should do and define what good means to the person. Pleasure and pain can be objectively determined since they are states and compared with one another on the basis of their duration, intensity, proximity, fecundity, certainty, and purity. Bentham asserted a “greatest happiness principle” or the “principle of utility” which concerns the usefulness of things or actions and how they promote general happiness. Happiness is defined as the absence of pain and presence of pleasure, and what we are morally obligated to do is any activity that promotes the greatest amount of happiness for the most people. Anything that does not maximize happiness is morally wrong in his system. In sum, his psychological view is that human beings are primarily motivated by pleasure and pain. This philosophy of utilitarianism has implications for law, rights, liberty, and government that are beyond the scope of this book. For an excellent discussion of Bentham’s work, please visit: http://www.iep.utm.edu/bentham/.

1.4.2. Motivation and Psychology

1.4.2.1. Arousal theory of motivation. Though we will definitely cover numerous psychological principles throughout this book, I want to introduce a few theories of motivation here. First, in terms of the arousal theory of motivation, we might wonder if there is a certain level of arousal at which we perform better. If our arousal level is low, we might become bored and seek out stimulating activities. If it is too high, such as being stressed for a test, we will engage in relaxation techniques, such as taking a deep breath, meditating, or tensing and relaxing our muscles. The key is determining our optimal level of arousal, which in turn affects our performance. How so? According to the Yerkes-Dodson Law, performance on easy and difficult tasks are initially enhanced as arousal increases but when it reaches higher levels, the two types of tasks separate. Performance on easy tasks remains favorable while performance on difficult tasks declines, possibly due to activation of the sympathetic nervous system, which controls our fight or flight response. So, at what level of arousal do we function best? The Yerkes-Dodson law predicts moderate levels of arousal (Yerkes & Dodson, 1908).

1.4.2.2. Incentive theory of motivation. Another important theory of motivation is called the incentive theory of motivation. We all like getting rewards, whether a compliment for a job well done, a raise in our hourly rate, an ‘A’ on the test we just took, etc. These external rewards or incentives are so strong, we have a theory of motivation built around them. Essentially, when we perform a behavior and are rewarded for it, there is an expectation that in the future, when we engage in that same behavior again, our behavior will be the same. So, when should we give the reward? Rewards should be given immediately or as close to that as possible. Recall from our earlier discussion of sources of motivation, that intrinsic factors can provide a push to achieving a goal. Likewise, internal states can affect the appeal of incentives. If we are full, getting a dessert for earning an ‘A’ on a test will be less attractive. If we are in a really good mood, depressing music will be less appealing.

1.4.2.3. Cognitive theory of motivation. Another way to think about motivated behavior is that it results from the active processing of information we obtain from the world around us. This is the basis of the cognitive theory of motivation and proposes that our expectations guide our behavior to bring about desirable outcomes. For this to happen, we have to gather information about our environment which involves the action of our sensory organs – that is sensed by our ears, eyes, nose, mouth, and skin. We can only detect or sense information available to us and this raw sensory data needs to have meaning attached to it. This is where perception, or the act of assigning meaning to raw sensory data, comes in. One’s personal history plays a role in this, too, and is used to make sense of current events by referencing similar past events we have encountered. This history is stored in our memory and accessed as needed. The cognitive theory takes on a few forms, which will be discussed later – goal setting theory and attribution theory. The expectancy-value theory states that a person’s likelihood to successfully complete a goal is dependent on their expectation of success, multiplied by how valuable they deem success to be for them. People who are positive about their success believe they have the knowledge and competency needed to complete the task, while those who are negative about their success, expect failure. In the case of the former, they will be highly motivated to achieve the goal since they expect to succeed, and it is important to them.

1.4.2.4. Drive-reduction theory of motivation. As the clock approaches noon each day, you likely begin to feel hunger pangs, especially if you skipped breakfast, ate light, or ate much earlier. What do you do? Simply, you go to the refrigerator or a restaurant and obtain sustenance. If this describes your actions, then you just confirmed the drive-reduction theory of motivation, or the idea that we are motivated to reduce a drive to restore homeostasis in the body and was based on the work of behaviorist Clark Leonard Hull (1884-1952). Simply, Hull said that a need arises from a deviation from optimal biological conditions and can include hunger, thirst, being cold or hot, or needing social approval. When this deviation occurs, we experience a drive or a state of tension, discomfort, or arousal that activates a behavior and with time, restores homeostasis, or balance. If we do not have enough glucose in our blood to support digging a ditch in our back yard, our body will produce a grumbling in our stomach or hunger pangs to let us know of the deficit, and then we will be motivated to obtain food to bring us back to balance and end the discomfort caused by the grumbles. And not just that! We also learn from this experience, too, such that in the future, when we experience hunger pangs, we know to go to the refrigerator to get food. Or if we are cold, we know we can start a fire in the wood stove or get a coat from the hall closet. Hull called this habit strength and said that connections are strengthened the more times that reinforcement has occurred. If we are cold and obtaining a jacket makes us warm again (as you will see later, this is called negative reinforcement or taking away something aversive which makes a behavior more likely in the future), then in the future, we will do the same.The more times we engage in this process of stimulus à response à positive consequence, the stronger the habit or association will be.

1.4.2.5. Instinct theory of motivation. At times, a person or animal will respond in predictable ways to certain stimuli, or as ethologists call it, an instinct. Instincts are inborn and inherited, such as with the phenomena of imprinting, observed by Konrad Lorenz. He noted that young geese will follow the first moving object they sense after birth. Though this is usually their mother, it may not be in all cases. Human beings do not possess this specific instinct. The instinct theory of motivation states that all our activities, thoughts, and desires are biologically determined or evolutionarily programmed through our genes and serve as our source of motivation. William McDougall (1871-1938) stated that humans are wired to attend to stimuli that are important to our goals, move toward the goal, such as walking to the refrigerator, and finally we have the drive and energy between our perception of a goal and then movement towards it.

On the other hand, Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) believed motivation centered on instinctual impulses reaching consciousness and exerting pressure, which, much like strain, is uncomfortable and leads to motivated behavior. Freud identified two types of instincts: 1) life instincts or Eros including hunger, thirst, sex, self-preservation, and the survival of the species, and all the creative forces that sustain life; and 2) death instincts or Thanatos which are destructive forces that can be directed inward as masochism or suicide or outward as hatred and aggression. When these instincts create pressure, it is interpreted as pain and its satisfaction or reduction results in pleasure. Our ultimate goal or pleasure is to minimize the excitation/pressure.

Sexual and aggressive instincts tend to be repressed in the unconscious due to societal norms against their expression, which could result in some type of punishment or anxiety. Still, they need to be satisfied to reduce the pressure they exert, and some ways Freud said this could be done was through humor containing aggressive or sexual themes or dreams. In the case of dreaming, the censorship relaxes during sleep but is not removed and so impulses do enter the content of dreams but are disguised. Despite the disguise, we can still satisfy many of our urges (i.e., dreams with sexual content).

Another perspective on instincts comes from American psychologist, William James (1842-1910) who was influential on the Functionalist school of thought in Psychology. Essentially, functionalism said that any structure or function that existed today, did so because it served an adaptive advantage to the organism, demonstrating the influence of Darwin’s theory of evolution on our field. James agreed with this and suggested the existence of 37 instincts. These include parental love, jealousy, sociability, play, curiosity, fear, sympathy, vocalization, and imitation. James begins Chapter 24 of his book, The Principles of Psychology, by saying, “INSTINCT is usually defined as the faculty of acting in such a way as to produce certain ends, without foresight of the ends, and without previous education in the performance.” Instincts aid in self-preservation, defense, or care for eggs and young, according to James.

For more on James and instincts, and for the complete list of instincts, check out:

Interestingly, the founder of the school of thought called Behaviorism, John B. Watson (1878-1958), initially accepted the idea of instincts and proposed 11 of them associated with behavior. That said, in 1929 he came to reject this notion and instead argued that instincts are socially conditioned responses and in fact, the environment is the cause of all behavior.

Finally, we are sometimes motivated by forces outside conscious awareness or what is called unconscious motivation. For Freud (1920), awareness occurs when motives enter consciousness, the focus of awareness, from either the preconscious, defined as the part of a person’s psyche that contains all thoughts, feelings, memories, and sensations or the unconscious, defined as the part of a person’s psyche not readily available to them. It is here that repressed thoughts and instinctual impulses are kept. For information to pass from the unconscious to the preconscious, it must pass a censor or gate keeper of sorts. Any mental excitations that make it to the gate/door and are turned away are said to be repressed. Even when mental events are allowed through the gate, they may not be brought into awareness. For that to occur, the eye of the conscious must become aware of them.

1.5. Understanding Motivation through Evolution

Section Learning Objectives

- Describe the thoughts of Darwin’s predecessors.

- Define natural selection.

- Clarify the role Malthus played in Darwin’s work.

- Discuss applications of evolutionary theory.

- Clarify the importance of universal human motives.

- Describe the universal motive of fear.

- Describe what we have learned about the universal appeal of music and related human behaviors.

1.5.1. Evolutionary Theory

In 1859 Charles Darwin (1809-1882) published his work, The Origin of Species. In it, he described how life had been on earth for a long time and had undergone changes to create new species, though these comments were not first proposed by him. In reality, geologists and paleontologists had been making this case for decades before. For instance, Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon (1707-1788) argued that life developed through spontaneous generation, if the conditions were right, such as in the hot oceans present on early Earth. Migration to the tropics occurred as the Earth cooled and it was during these movements that life changed. Why was that? The basic mold that contained the organic particles making up each species changed as the organisms moved and different particles were available. He did not propose that radical changes to body plans occurred as a result, but it could explain how similar species lived in geographical areas around the world. Though his ideas did not stand the test of time due to limited evidence naturalists of the time had, they did foreshadow many of the major discoveries to come in the decades that followed.

Jean Baptiste Lamarck (1744-1829) stated that organisms had to change in response to changes in their environment. He explained the long necks of giraffes as having occurred due to the need to reach higher and higher leaves on trees. Lamarck also believed that organisms were driven to more complex forms and that blind primal forces are what led to such evolution, not the benevolent design of God, which was a slap in the face of British naturalists. He finally stated that these modifications were passed on to later generations.

In the 19th century, geologist Charles Lyell (1797-1875) proposed the concept of uniformitarianism which stated that the process which led to changes in the earth is uniform through time. To get to the structure or form the earth has today, it had to pass through stages of development. His ideas represented an application of evolution to geological theory.

Though a more thorough discussion of the ideas before Darwin is possible, we will move to Darwin and his theory of evolution in keeping with the primary focus of this book. It was hinged on the idea of natural selection or that individuals in a species show a wide range of variation due to differences in their genes and that those with characteristics better suited to their environment will survive and pass these traits on to successive generations. Any species that do not adapt to their environment, will not survive, but those that do adapt will evolve over time. Darwin’s ideas were greatly influenced by the work of Thomas Malthus (1766-1834) who in 1789 published his book, An Essay on the Principle of Population. In it, Malthus stated that a population grows quicker than its ability to feed itself, such that the population grows geometrically while the food supply grows arithmetically. Due to this, many people will live in near-starvation conditions and only the most cunning will survive. The same principles related to fertility and starvation that served as laws of human behavior related to other species as well. It was these ideas that Darwin applied to his theory of evolution.

Francis Galton (1822-1911) applied Darwin’s ideas to the inheritance of genius. In Hereditary Genius (1869) Galton proposed that genius, and the specific type, occurred too often in families to be explained by the environment alone. As such, the most fit individuals in a society could be “encouraged” to breed which would lead to an improvement of inherited traits of the human race over generations. This strategy was called eugenics.

Another application of Darwin’s ideas to human nature, as well as social, political, and economic issues, was social Darwinism, or the idea that like plants and animals, humans, also compete in a struggle for existence and a survival of the fittest is brought about by natural selection. Advocates state that governments should not regulate the economy or end poverty as it interferes with human competition. They, instead, believe in a laissex-faire economic system that favors competition and self-interest, where business and social affairs were concerned. Herbert Spencer (1820-1903) was one such proponent of social Darwinism and believed that people and organizations should be allowed to develop on their own, much like plants and animals have to adapt to their environment. Those that do not adapt successfully would die out or become extinct, leading to an improvement of society. In his book, Social Statistics (1850), he asserted that competition would lead to social evolution and produce prosperity and personal liberty, greater than during any other time in human history. Though his work began in Britain during the mid-19th century, he quickly gained support in the United States and influenced such men as Andrew Carnegie, who hosted him during a visit in 1883.

1.5.2. Universal Human Motives

We defined motives earlier in this module. As a review, a motive is an individual’s natural proclivity to approach things that are positive while avoiding those that are negative. In this section we look at some universal motives and so need to explain what makes a motive universal. Simply, it must be displayed by people regardless of their culture or country of origin. This is not to say that it cannot be displayed differently, but that it has to be displayed in some way. For a motive to survive, it must be passed from generation to generation through genes and serve some adaptive advantage for the species, in this case, human beings. Examples include facial expressions which we will discuss more in Module 2, setting goals which will be discussed in Module 3, the formation of relationships, the expression of fear, and food preferences, to name a few. Though we will talk about several of these universal motives throughout this book, let’s spend a little time on two of them – fear and music.

1.5.2.1. The universal motive of fear. What is fear? The DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition) defines fear as the emotional response to a real or perceived threat and is associated with autonomic nervous system (ANS) arousal needed for fight or flight, due to an immediate danger (APA, 2013). The ANS regulates functioning of blood vessels, glands, and internal organs such as the bladder, stomach, and heart and consists of the of Sympathetic and Parasympathetic nervous systems, the former which is involved when a person is intensely aroused and controls the flight-or-fight instinct. A distinction between fear and anxiety is necessary, such that anxiety is the anticipation of future threat and only involves preparation for future danger and avoidant behaviors (APA, 2013).

Fears can be learned or conditioned too. How so? One of the most famous studies in psychology was conducted by Watson and Rayner (1920). Essentially, they wanted to explore “the possibility of conditioning various types of emotional response(s).” The researchers ran a 9-month-old child, known as Little Albert, through a series of trials in which he was exposed to a white rat, to which no response was made outside of curiosity and to a loud sound to which he exhibited fear. On later trials, the rat was presented and followed closely by the loud sound. After several conditioning trials, the child responded with fear to the mere presence of the white rat.

As fears can be learned, so too, they can be unlearned. Considered the follow-up to Watson and Rayner (1920), Jones (1924) wanted to see if a child who learned to be afraid of white rabbits, could be conditioned to become unafraid of them. Simply, she placed the child in one end of a room and then brought in the rabbit. The rabbit was far enough away so as to not cause distress. Then, Jones gave the child some pleasant food (i.e., something sweet such as cookies). The procedure continued with the rabbit being brought in a bit closer each time and eventually the child did not respond with distress to the rabbit. This process is called counterconditioning, or the reversal of previous learning.

Fears serve an adaptive advantage as they lead to greater survival of the species since the fear is activated in aversive contexts, is automatic, is mostly “impenetrable to cognitive control,” and originates in a specific area of the brain called the amygdala (Mineka & Ohman, 2002; Ohman & Mineka, 2001). It should not be surprising that threatening stimuli (i.e. a snake or spider) capture our attention quicker than fear-irrelevant stimuli such as a flower or mushroom (Fox, Russo, & Dutton, 2002; Ohman, Flykt, & Esteves, 2001; Fox, Lester, Russo, Bowles, Pichler, & Dutton, 2000). We are also prepared to learn some associations over others, or that we are biologically prepared to do so, a term coined by Martin Seligman (1971). For instance, we are more likely to become afraid of a snake than we are of a butterfly. Why? The snake is more likely to kill us than a butterfly is.

1.5.2.2. The universal appeal of music, mother, and native language. DeCasper and Spence (1986) recruited 33 healthy women who were about 7.5 months pregnant. The women were familiarized with three short children’s stories and then tape recorded each. Once done, they were assigned one of the stories as her target story so that she did not bias the recording of their target through such means as exaggerated intonation. The women read the target story aloud two times each day when they felt the fetus was awake, and in a quiet environment so that no other sounds could be heard. The stories included The King, the Mice, and the Cheese by Gurney and Gurney, the first 28 paragraphs of The Cat in the Hat by Dr. Seuss, and The Dog in the Fog. All three stories were approximately the same length and contained equal sized vocabularies. During the postnatal phase, sixteen of the 33 fetal subjects were tested as newborns. It was determined that they had been exposed to the target story approximately 67 times or for 3.5 hours total prenatally. During postnatal testing the newborns were placed in a quiet, dimly lit room where they lay supine and listened to a tape recording of the target story. They were tested as to whether the sounds of the recited passage were more reinforcing than a novel passage. Results showed that as hypothesized, the target story (previously recited) was more reinforcing and that this was independent of who recited the story. The authors concluded that “the target stories were the more effective reinforcers, that is, were preferred, because the infants had heard them before birth” (pg. 143).

Relatedly, Moon, Cooper, and Fifer (1993) showed that two-day-old infants preferred their native language over a foreign one while other lines of research have shown that newborns prefer their mother’s voice over that of another female (Fernald, 1985; DeCapser and Fifer, 1980). Not just that, neonates or newborns, prefer the mother’s face as well (Bushneil, Sai, & Mullin, 1989)! Could these findings – the ability to hear in the womb, a preference for one’s own language, and the recognition of our mother – serve an adaptive advantage for human beings?

Now to the issue of music preference. Nakata and Trehub (2004) presented six -month- old infants with audiovisual episodes of their mother talking or singing to them. Results showed that between the two forms of infant-directed communication, babies preferred signing over talking, which may also positively affect emotional coordination between mother and child. Shannon (2006) found infant directed signing to be as effective in sustaining attention as book reading or toy play with mothers. In terms of consonant (harmonious) and dissonant (inharmonious) music, research shows that babies prefer consonant sounds (Zentner & Kagan, 1998; Trainor & Heinmiller, 1998). The same is true in infant chimpanzees (Sugimoto et al., 2010), suggesting that the preference for consonance is not unique to humans.

In Module 2, we will discuss the universal recognition of basic human emotions through facial expressions. Related to our current discussion, the emotions of happy, sad, and scared/fearful have been found to be universally recognized in music. Fritz et al. (2009) conducted a cross-cultural study involving Western participants and participants from a native African population (the Mafa). Both groups were naïve to the music of the other group. The results showed that the Mafas recognized the three emotions in Western music excerpts and that consonance is preferred and universally influences the perception of pleasantness in music.

1.6. Researching Motivation

Section Learning Objectives

- Define scientific method.

- Outline and describe the steps of the scientific method, defining all key terms.

- Identify and clarify the importance of the three cardinal features of science.

- List the five main research methods used in psychology.

- Describe observational research, listing its advantages and disadvantages.

- Describe case study research, listing its advantages and disadvantages.

- Describe survey research, listing its advantages and disadvantages.

- Describe correlational research, listing its advantages and disadvantages.

- Describe experimental research, listing its advantages and disadvantages.

- State the utility and need for multimethod research.

1.6.1. The Scientific Method

Psychology is the scientific study of behavior and mental processes. We will spend quite a lot of time on the behavior and mental processes part and how motivation relates to them., but before we proceed, it is prudent to elaborate more on what makes psychology scientific. In fact, it is safe to say that most people not within our discipline or a sister science, would be surprised to learn that psychology utilizes the scientific method at all.

As a starting point, we should expand on what the scientific method is.

The scientific method is a systematic method for gathering knowledge about the world around us.

The key word here is that it is systematic meaning there is a set way to use it. What is that way? Well, depending on what source you look at, it can include a varying number of steps. I like to use the following:

Table 1.2: The Steps of the Scientific Method

| Step | Name | Description |

| 0 | Ask questions and be willing to wonder. | To study the world around us you have to wonder about it. This inquisitive nature is the hallmark of critical thinking, or our ability to assess claims made by others and make objective judgments that are independent of emotion and anecdote and based on hard evidence, and required to be a scientist. |

| 1 | Generate a research question or identify a problem to investigate. | Through our wonderment about the world around us and why events occur as they do, we begin to ask questions that require further investigation to arrive at an answer. This investigation usually starts with a literature review, or when we conduct a literature search through our university library or a search engine such as Google Scholar to see what questions have been investigated already and what answers have been found, so that we can identify gaps or holes in this body of work. |

| 2 | Attempt to explain the phenomena we wish to study. | We now attempt to formulate an explanation of why the event occurs as it does. This systematic explanation of a phenomenon is a theory and our specific, testable prediction is the hypothesis. We will know if our theory is correct because we have formulated a hypothesis, which we can now test.

|

| 3 | Test the hypothesis. | It goes without saying that if we cannot test our hypothesis, then we cannot show whether our prediction is correct or not. Our plan of action of how we will go about testing the hypothesis is called our research design. In the planning stage, we will select the appropriate research method to answer our question/test our hypothesis.

|

| 4 | Interpret the results. | With our research study done, we now examine the data to see if the pattern we predicted exists. We need to see if a cause-and-effect statement can be made, assuming our method allows for this inference. More on this in Section 2.3. For now, it is important to know that the statistics we use take on two forms. First, there are descriptive statistics which provide a means of summarizing or describing data and presenting the data in a usable form. You likely have heard of the mean or average, median, and mode. Along with standard deviation and variance, these are ways to describe our data. Second, there are inferential statistics which allow for the analysis of two or more sets of numerical data to determine the statistical significance of the results. Significance is an indication of how confident we are that our results are due to our manipulation or design and not chance. |

| 5 | Draw conclusions carefully. | We need to accurately interpret our results and not overstate our findings. To do this, we need to be aware of our biases and avoid emotional reasoning so that they do not cloud our judgment. How so? In our effort to stop a child from engaging in self-injurious behavior that could cause substantial harm or even death, we might overstate the success of our treatment method. |

| 6 | Communicate our findings to the larger scientific community. | Once we have decided on whether our hypothesis is correct or not, we need to share this information with others so that they might comment critically on our methodology, statistical analyses, and conclusions. Sharing also allows for replication or repeating the study to confirm its results. Communication is accomplished via scientific journals, conferences, or newsletters.

|

Science has at its root three cardinal features that we will see play out time and time again throughout this book. They are:

- Observation – In order to know about the world around us, we must be able to see it firsthand. When an individual is afflicted by a mental disorder, we can see it through the overt behavior they make. An individual with depression may be motivated to withdraw from activities they enjoy, those with social anxiety disorder will avoid social situations, people with schizophrenia may express concern over being watched by the government, and individuals with dependent personality disorder may wait to make any decision in life until trusted others tell them what to do. In these examples, and numerous others we can suggest, the behaviors that lead us to a diagnosis of a specific disorder can easily be observed by the clinician, the patient, and/or family and friends.

- Experimentation – To be able to make causal or cause-and-effect statements, we must isolate variables. We must manipulate one variable and see the effect of doing so on another variable. Let’s say we want to know if a new treatment for bipolar disorder is as effective as existing treatments…or more importantly, better. We could design a study with three groups of bipolar patients. One group would receive no treatment and serve as a control group. A second group would receive an existing and proven treatment and would also be considered a control group. Finally, the third group would receive the new treatment and be the experimental group. What we are manipulating is what treatment the groups get – no treatment, the older treatment, and the newer treatment. The first two groups serve as controls since we already know what to expect from their results. There should be no change in bipolar disorder symptoms in the no treatment group, a general reduction in symptoms for the older treatment group, and the same or better performance for the newer treatment group. As long as patients in the newer treatment group do not perform worse than their older treatment counterparts, we can say the new drug is a success. You might wonder why we would get excited about the performance of the new drug being the same as the old drug. Does it really offer any added benefit? In terms of a reduction of symptoms, maybe not, but it could cost less money than the older drug and so that would be of value to patients.

- Measurement – How do we know that the new drug has worked? Simply, we can measure the person’s bipolar disorders symptoms before any treatment was implemented, and then again once the treatment has run its course. This pre-post- test design is typical in drug studies.

1.6.2. Research Designs Used in Psychology

Step 3 called on the scientist to test his or her hypothesis. Psychology as a discipline uses five main research designs. They are:

1.6.2.1. Naturalistic and laboratory observation. In terms of naturalistic observation, the scientist studies human or animal behavior in its natural environment, which could include the home, school, or a forest. The researcher counts, measures, and rates behavior in a systematic way and at times uses multiple judges to ensure accuracy in how the behavior is being measured. The advantage of this method is that you see behavior as it occurs, and it is not tainted by the experimenter. The disadvantage is that it could take a long time for the behavior to occur and if the researcher is detected, then this may influence the behavior of those being observed. Laboratory observation involves observing people or animals in a laboratory setting. The researcher might want to know more about parent-child interactions and so brings a mother and her child into the lab to engage in pre-planned tasks such as playing with toys, eating a meal, or the mother leaving the room for a short period of time. The advantage of this method over naturalistic method is that the experimenter can use sophisticated equipment and videotape the session to examine it later. The problem is that since the subjects know the experimenter is watching them, their behavior could become artificial.

1.6.2.2. Case studies. Psychology can also utilize a detailed description of one person or a small group, based on careful observation. This was the approach the founder of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud, took to develop his theories. The advantage of this method is that you arrive at a rich description of the behavior being investigated but the disadvantage is that what you are learning may be unrepresentative of the larger population and so lacks generalizability. Again, bear in mind that you are studying one person or a very small group. Can you possibly make conclusions about all people from just one or even five or ten? The other issue is that the case study is subject to the bias of the researcher in terms of what is included in the final write up and what is left out. Despite these limitations, case studies can lead us to novel ideas about the cause of motivated behavior.

1.6.2.3. Surveys/Self-Report data. This is a questionnaire, consisting of at least one scale, with some number of questions which assess a psychological construct of interest such as parenting style, depression, locus of control, or sensation seeking behavior. It may be administered by paper and pencil or computer. Surveys allow for the collection of large amounts of data quickly, but the actual survey could be tedious for the participant and social desirability, when a participant answers questions dishonestly so that they are seen in a more favorable light, could be an issue. For instance, if you are asking high school students about their sexual activity, they may not give genuine answers for fear that their parents will find out. You could alternatively gather this information via an interview in a structured or unstructured fashion.

1.6.2.4. Correlational research. This research method examines the relationship between two variables or two groups of variables. A numerical measure of the strength of this relationship is derived, called the correlation coefficient, and can range from -1.00, a perfect inverse relationship meaning that as one variable goes up the other goes down, to 0 or no relationship at all, to +1.00 or a perfect relationship in which as one variable goes up or down so does the other. In terms of a negative correlation, we might say that as a parent becomes more rigid, controlling, and cold, the attachment of the child to parent goes down. In contrast, as a parent becomes warmer, more loving, and provides structure, the child becomes more attached. The advantage of correlational research is that you can correlate anything. The disadvantage is that you can correlate anything. Variables that really do not have any relationship to one another could be viewed as related. Yes, this is both an advantage and a disadvantage. For instance, we might correlate instances of making peanut butter and jelly sandwiches with someone we are attracted to sitting near us at lunch. Are the two related? Not likely, unless you make a really good PB&J, but then the person is probably only interested in you for food and not companionship. J The main issue here is that correlation does not allow you to make a causal statement.

1.6.2.5. Experiments. This is a controlled test of a hypothesis in which a researcher manipulates one variable and measures its effect on another variable. The variable that is manipulated is called the independent variable (IV) and the one that is measured is called the dependent variable (DV). In the example above, the treatment for bipolar disorder was the IV while the actual intensity or number of symptoms serves as the DV. A common feature of experiments is to have a control group that does not receive the treatment or is not manipulated and an experimental group that does receive the treatment or manipulation. If the experiment includes random assignment, the participants have an equal chance of being placed in the control or experimental group. The control group allows the researcher (or teacher) to make a comparison to the experimental group, make our causal statement possible and stronger. In our experiment, the new treatment should show a marked reduction in the intensity of bipolar symptoms compared to the group receiving no treatment, and perform either at the same level as, or better than, the older treatment. This would be the hypothesis with which we begin the experiment.

There are times when we begin a drug study, and to ensure participant expectations have no effect on the final results through giving the researcher what they are looking for (in our example, symptoms improve whether or not a treatment is given or not), we use what is called a placebo, or a sugar pill made to look exactly like the pill given to the experimental group. This way, all participants are given something, but cannot figure out what exactly it is. You might say this keeps them honest and allows the results to speak for themselves.

1.6.2.6. Multi-method research. As you have seen above, no single method alone is perfect. All have their strengths and limitations. As such, for the psychologist to provide the clearest picture of what is affecting motivated behavior and the mental processes underlying it, several of these approaches are typically employed at different stages of the research study. This is called multi-method research.

As we tackle the many ways we engage in motivated behavior throughout this book, you will see all of these designs discussed at some point. In fact, you might have already seen a few mentioned in Sections 1.1 to 1.5.

Module Recap

In this first module we defined motivation as when we are moved into action. People loosely and incorrectly use the expression, ‘I am unmotivated,’ to indicate a complete lack of motivation when what they really mean is that they are motivated but toward other ends. Instead of studying for an exam, students may want to surf the internet or hang with friends. To avoid yard work, a husband may decide to play with his kids. When we do act, we are under the influence of both internal (push) and external (pull) forces. In the case of push, deficiencies in a required resource cause a need. Our brain creates a drive or state of tension which produces motivated behavior. So, we take a drink (behavior) when we are parched (drive) to restore water to our system (need). In the case of pull, incentives are used to motivate our behavior, as say your parents offering to pay you $50 for each ‘A’ earned in your classes.

We can think of why we engage in motivated behavior from a few different perspectives. First, people are driven to satisfy their needs, whether they are more biological in nature or psychological. Our needs are arranged in a hierarchy and those at the base of the pyramid need to be met before higher level needs can be. If this does not happen, the pyramid, like a house, collapses in on itself…or does it? Next, we may be inclined to simply reduce the tension or drive, much like how a thermostat detects how hot or cold it is in our house and takes steps to bring it to our desired temperature. Or maybe we are motivated to behave at a level of arousal that maximizes performance.

We also saw how time – past, present, and future – motivates our behavior. The behavior we engage in has, at its root, evolution and the survival of the species. Several types of motivated behaviors are expressed by all people and so are universal in nature. We might investigate these behaviors, and others, using any of the research designs mentioned in this module and by using the scientific method.

I hope you enjoyed the first module in this book. We will finish up Part 1 by discussing the complementary piece to motivation – emotion. After this, we will tackle the important topics of goal motivation, stress and coping, and the economics of motivated behavior. This leads us to a discussion of behavior change and how it can motivate us in important ways. More on Parts III to V later.

Lee Daffin

2nd edition