Module 11: Motivation and Health and Wellness

Module Overview

Module 11 covers the interesting topic of health and wellness, two terms we all can relate to even if you do not realize, at this time, that they are not the same thing. We will start by making that distinction and then discuss the eight dimensions of wellness. From there, I will show how motivated behavior occurs in relation to seeking medical attention or information, adhering to doctor’s orders, pain management, and using complementary and alternative practices.

Note to WSU Students: The topic of this module overviews what you would learn in PSYCH 320: Health Psychology at Washington State University.

Module Outline

- 11.1. Dimensions of Wellness

- 11.2. Motivated to Seek Medical Attention/Information

- 11.3. Motivated to Follow Doctor’s Orders

- 11.4. Motivated by Pain Relief

- 11.5. Pursuing Alternative Forms of Medical Care

Module Learning Outcomes

- Distinguish between health and wellness and list the dimensions of wellness.

- Clarify why or why not people seek medical information/care and in the case of information, what sources are used beyond a medical professional.

- Explain adherence, barriers to it, and ways to improve it.

- Define pain, its types, and ways to mange it.

- List and describe alternatives to traditional medicine.

11.1. Dimensions of Wellness

Section Learning Objectives

- Contrast health and wellness.

- List and describe the dimensions of wellness.

- Exemplify ways wellness relates to behavior change.

You have likely heard the terms health and wellness before. Most people believe these are synonyms for one another but in reality, they are very different. First, health can be defined as the absence of disease and is seen as a state someone is in. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) defines wellness as “being in good physical and mental health.” They add, “Remember that wellness is not the absence of illness or stress. You can still strive for wellness even if you are experiencing these challenges in your life.” Wellness is a mindset and includes the choices we consciously make for better or worse. From this perspective, we need wellness for health and let’s say we are depressed or sore. Wellness, through our choices, can help restore our good health again.

Most people see wellness as just focused on the physical or mental. These are part of the picture, but not the whole picture. SAMHSA proposes eight dimensions of wellness as follows (this information is directly from their website):

- Physical – Recognizing the need for physical activity, healthy foods, and sleep.

- Emotional – Coping effectively with life and creating satisfying relationships.

- Environmental—Good health by occupying pleasant, stimulating environments that support well-being

- Financial—Satisfaction with current and future financial situations

- Intellectual—Recognizing creative abilities and finding ways to expand knowledge and skills

- Occupational—Personal satisfaction and enrichment from one’s work

- Social— Developing a sense of connection, belonging, and a well-developed support system

- Spiritual— Expanding a sense of purpose and meaning in life

Source: https://www.samhsa.gov/wellness-initiative/eight-dimensions-wellness

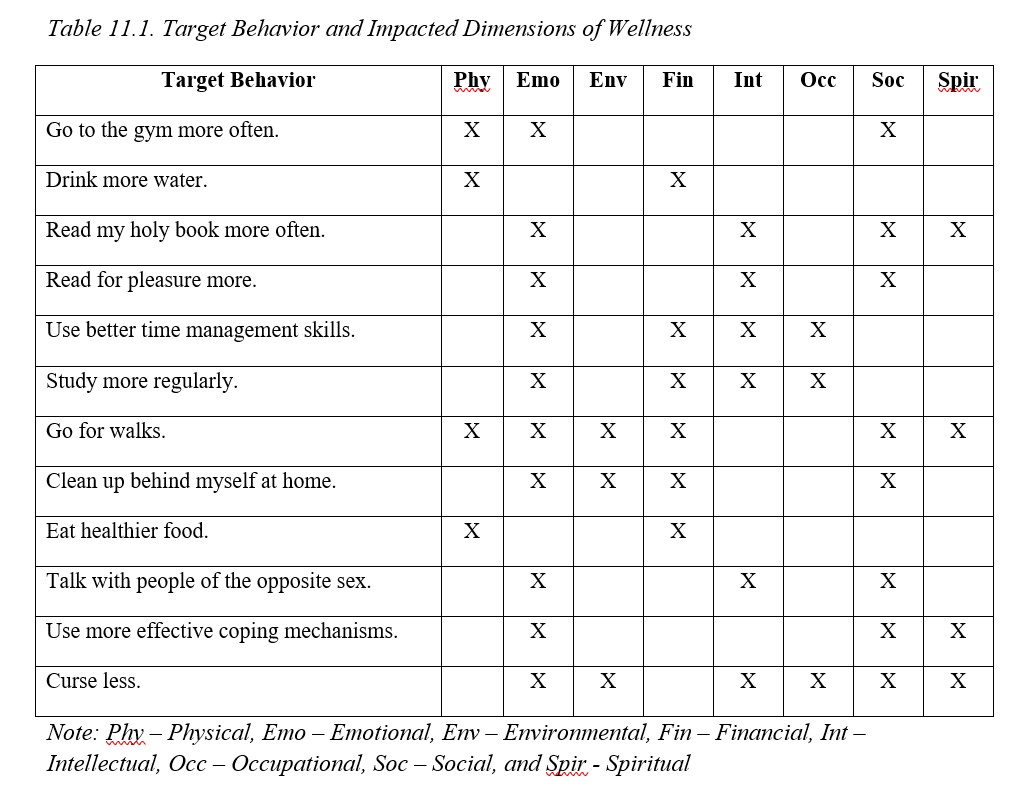

How might the dimensions of wellness relate to motivated behavior? Consider what you learned in Module 6 about behavior modification. The following are some target behaviors a person may wish to change for the better and which dimension(s) of wellness could be affected:

You could make a case for other dimensions on some of these, but I am sure the bigger issue is that you might be thinking how in the world could that dimension relate to that target behavior? I do not wish to spend a lot of time on the 12 target behaviors I used as examples explaining why I selected these various dimensions of wellness, so I will just cover four. You can think critically about the other 8 behaviors, and others you might decide are worth changing.

- Go for walks – Physical is obvious. Emotional might be too but this is an opportunity to get away from life and destress. If you go for a walk in a park, you are communing with nature which is environmental and potentially spiritual. If you go with another person, you are working on social and while walking you could engage in a conversation of current issues which is intellectual. Financial is on the list because unlike going to the gym, walking outside is free.

- Read a holy book – This can help you find meaning and purpose in life which is spiritual or to discover another coping mechanism which is emotional. If you are in a Bible study group this is social and intellectual, and as for the latter, you will discuss what individual passages mean on a personal and general level.

- Cleaning up behind myself at home – If you are staying clean you save yourself needless stress of angry roommates which is emotional. Respecting your roommates and their wishes is social. A clean house is part of environmental wellness. Keeping clean means you guarantee yourself a place to live which ties into financial wellness, as having to find another place to live may cost you more money.

- Study more regularly – Emotional in regards to stress reduction. If you fail a class you have to pay to repeat it which impacts financial wellness. Intellectual in terms of mastering material related to your major. Better grades open up more doors when you start applying for jobs and so occupational wellness.

As you can see, you get quite a lot of bang for your buck when you bring about positive behavioral change. But outside of changing our behavior, motivated behavior occurs in relation to seeking medical attention, adhering to doctor’s orders, the perception and regulation of pain, stress management, and a few choice health defeating or promoting behaviors. All will be discussed in due time.

11.2. To Seek or Not to Seek…. Medical Attention/Information

Section Learning Objectives

- Differentiate illness and disease.

- State factors on whether we seek medical care or information.

- Evaluate the quality of sources of information outside a medical practitioner.

Let’s face it. Most of us only go to the doctor when something is wrong. We might be sick with the flu, have injured our finger hanging gutters, or are having trouble breathing. Another distinction is needed – between illness and disease. In the case of illness, we are sick and have been diagnosed as so. When there is physical damage within our body, we are said to have a disease. In the case of the former, think about having a cold and for the latter, consider the impact of cancer say on our lungs. For many of us, we have a disease but show no obvious symptoms meaning we do not appear ill. Diabetes involves problems with the production of or response to insulin. According to the American Diabetes Association, in 2015 about 30.3 million Americans (or 9.4% of the population) had diabetes and of this, about 7.2 million or a quarter, did not know they had it. This speaks to the fact that though we have a disease we may not experience illness. In fact, prediabetes affects 84.1 million Americans and is when “blood glucose levels are higher than normal but not yet high enough to be diagnosed as diabetes.” Prediabetes has no clear symptoms, and many do not know they have it.

For more on diabetes, see the American Diabetes Association website:

http://www.diabetes.org/diabetes-basics/statistics/

A doctor or other medical professional diagnoses a patient’s condition based on the symptoms they have, thereby determining their health status. But what factors affect our decision to seek medical care/information?

- Stress – In a longitudinal study of 43-to-92-year-old participants, investigators found that medical care was less sought out if ambiguous symptoms experienced during the previous week were attributed to a life stressor that began within the previous 3 weeks. Participants believed the symptoms were due to stress and not illness. If the stressor began longer than three weeks ago (or was not recent) they sought medical advice and also did so if the symptoms were clearly linked to a disease as it was perceived as a health threat (Cameron, Leventhal, & Leventhal, 1995).

- Personality – People higher in neuroticism were found to be more likely to report symptoms and to seek care from a doctor than those low in the trait (Freidman et al. 2013).

- Gender – Stevens et al. (2012) found that among adults aged 65 years and older, significantly more women reported falling, sought medical care, and/or talked with their doctor about falls and how to prevent them. Similarly, women were found to be more likely to visit their general practitioner to discuss mental health problems while a range of socio-demographic and psychological factors affected the decision for men (Doherty and Kartalova-O’Doherty, 2011).

- Stigma – People suffering from mental illness often do not seek medical attention they need due to stigma (Corrigan, Druss, & Perlick, 2014), or when negative stereotyping, labeling, rejection, and loss of status occur. Stigma takes on three forms. Public stigma occurs when members of a society endorse negative stereotypes of people with a mental disorder and discriminate against them. They might avoid them all together resulting in social isolation. In order to avoid being labeled as “crazy” or “nuts” people needing care may avoid seeking it altogether or stop care once started, called label avoidance. Finally, self-stigma occurs when people with mental illnesses internalize the negative stereotypes and prejudice, and in turn, discriminate against themselves. Another form of stigma that is worth noting is that of courtesy stigma or when stigma affects people associated with the person with a mental disorder. Karnieli-Miller et. al. (2013) found that families of the afflicted were often blamed, rejected, or devalued when others learned that a family member had a serious mental illness (SMI). Due to this they felt hurt and betrayed and an important source of social support during the difficult time had disappeared, resulting in greater levels of stress. To cope, they had decided to conceal their relative’s illness and some parents struggled to decide whether it was their place to disclose versus the relative’s place. Others fought with the issue of confronting the stigma through attempts at education or to just ignore it due to not having enough energy or desiring to maintain personal boundaries. There was also a need to understand responses of others and to attribute it to a lack of knowledge, experience, and/or media coverage. In some cases, the reappraisal allowed family members to feel compassion for others rather than feeling put down or blamed. The authors concluded that each family “develops its own coping strategies which vary according to its personal experiences, values, and extent of other commitments” and that “coping strategies families employ change over-time.”

- Age – As discussed in Module 10, young adults are in the prime of their life and though some declines occur, the declines are modest and do not generally affect functioning. As such, it should not be surprising to learn that this age group generally does not seek medical care when needed. As we age, we try to distinguish symptoms as being due to age or disease. For instance, if my knee is hurting, do I as a 42-year old male attribute this to wear and tear from working out 5 days a week for two decades, or could there be a more serious issue going on? Generally, when our symptoms are gradual and mild, we see this as being due to age but if they are sudden and severe, we see this as being related to disease and more serious. In the case of the latter, we seek advice from a doctor.

- Religiosity – In a study of 129 African American women aged 30-84 years, Gullatte et al. (2010) found that women who were less educated, unmarried, and spoke with God only about their self-detected breast change, were significantly more likely to delay seeking medical care. When women disclosed the symptom to another person, they were more likely to consult with their doctor. Delays of three months or more in seeking medical care led to presenting with a later stage of breast cancer.

- Symptomology – Might how our symptoms present affect the manner in which we respond to a disease and whether or not we seek medical care? They do and in general, if a symptom is easily seen, perceived as more severe, interferes significantly in the person’s life, and is frequent, then we will seek medical treatment (Mechanic, 1978). To illustrate the effect of symptomology on one’s life, Ferreira et al. (2012) found that across eleven studies, patients with a high level of disability were about 8 times more likely to seek care than those with lower levels of disability. Women were also slightly more likely to seek care for back pain as were those with a history of back problems.

Finally, if we have made the decision to seek medical information, this does not necessarily mean we will do so from a doctor. In the 21st century many seek their information from the internet and sites such as WebMD. But how reliable is this information? Ogah and Wassersug (2013) reviewed 43 noncommercial websites that provided information on treatment options for individuals suffering from prostate cancer and assessed how comprehensive the site was based on the information provided about alternative hormonal therapies such as GnRH antagonists and estrogen. Very few sites presented information on alternative therapies to the standard treatment for androgen suppression and less than half provided time stamps to indicate when they were last updated. Many sites were also outdated in their information.

What about Wikipedia? A study assessing content on 10 mental health topics from 14 websites to include Wikipedia found that across all topics, Wikipedia was the most highly rated in all domains but readability. It appears that the quality of information on this website is as good as, or even better than, the information found on websites such as Encyclopedia Britannica or a textbook of psychiatry (Reavley et al, 2012).

Outside of the internet, concerned parties use other sources to include family members; support groups; traditional media sources such as television, radio, books, brochures, or medical journals; and telephone hotlines. These sources are also compared against one another for reasons to include verification or double-checking of information, clarification/elaboration or gaining additional information, emotional support, directed contact or when one source directs patients to another source, and proxy/surrogacy or when information is sought on behalf of the patient from family or friends (Nagler et al., 2011).

11.3. Motivated to Follow Doctor’s Orders

Section Learning Objectives

- Explain the concept of adherence.

- State barriers to adherence, or those that encourage non-adherence.

- Clarify consequences of non-adherence.

- Describe ways to increase adherence.

Well, I have to say that the title of this section is fitting. How many times do we go to the doctor, and are told to lose weight or quit smoking? Sometimes I think they spend a year in medical school just learning lines like this to deliver when we have an appointment with them. But it is good advice. Maybe we do need to lose weight, exercise, stop a bad behavior, or whatever else we need to change. How many of us actually do it? What gives us the motivation to follow our doctor’s orders or to stick to this advice/guidance? In the realm of health psychology this is called adherence and includes not only our willingness or motivation to follow orders, but our ability to do so. Recall in Module 6 sometimes we are highly motivated to make a change but do not have the knowledge or competence to do so. This is where ability factors in. Outside of simply following doctor’s orders when we see him/her, we also need to schedule our regular checkups with our primary care physician, dentist, and eye doctor. Most people go to the doctor only when something is wrong, much like we do with our car, outside of possibly getting the oil change at the proper time. So, adherence is an important topic to discuss within the realm of health and wellness.

In a 2003 report the World Health Organization (WHO) found that on average 50% of people living in developed countries adhered to taking their medications as prescribed (Sabate, 2003). There are numerous reasons why people do or do not adhere. The WHO classifies these reasons into five main categories (socioeconomic factors, factors associated with the health care team and system in place, disease-related factors, therapy-related factors, and patient-related factors; Sabate, 2003) which Brown and Bussell (2011) roll up into three broader categories:

- Patient-Related Factors – These include patients not understanding their disease, their perception of how severe the disease is (DiMatteo, Haskard, & Williams, 2007), beliefs about the effectiveness of treatment, fear of becoming dependent on the drug, a lack of motivation, not being involved in decisions related to their treatment regimen, cost of the medications, and not understanding the instructions or label (Osterberg & Blaschke, 2005). Patient self-efficacy, or our sense of whether we have the skills necessary to achieve the goal, in this case taking our medication, affect adherence such that those with higher self-efficacy stick with it, while those who are lower in it do not, as is the case in one study examining patience adherence to new HIV treatments (Catz et al., 2000). In terms of patient personality and the domains of the Five Factor Model, Conscientiousness was found to be related to better adherence (Eustace et all, 2018; Christensen and Smith, 1995).

- Physician-Related Factors – Doctors complicate matters by prescribing complex treatment regimens and not involving the patient in the decision- making process. They also do not adequately explain the benefits of the drugs or its side effects (Catz et al., 2000) or consider the financial burden on their patients. So, what can be done to improve adherence from a patient perspective? Kripalani et al. (2008) found that lowering medication costs, a follow-up call, transportation to the pharmacy, pharmacist counseling when picking up the prescription, and a pillbox would help. Communication is even more key to encouraging adherence in older adults (Williams, Haskard, &DiMatteo, 2007).

- Health System/Team Building-Related Factors – A lack of health care coordination, access to care, prohibitive drug costs, excessive copayments, and feeling rushed out so that the doctor can move on to the next patient all contribute to non-adherence (Kennedy, Tuleu, & Mackay, 2008).

Is adherence really that important? The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services AID’s Information website states that taking HIV medicines gives the drugs the chance to prevent HIV from multiplying and doing irreparable damage to the immune system. Also, poor adherence increases the risk of drug resistance and once it develops, remains in the body. “Drug resistance limits the number of HIV medicines available to include in a current or future HIV regimen.” Taking the prescribed medications daily prevents HIV from multiplying, reducing the risk that the disease will mutate and produce drug-resistant HIV. They say, “Research shows that a person’s first HIV regimen offers the best chance for long-term treatment success. Adherence is important from the start—when a person first begins taking HIV medicines.” Some other reasons they offer for non-adherence include depression, fear of the stigma associated with having HIV, an unstable housing situation, alcohol or drug use, and a lack of health insurance.

For more on HIV drug adherence, please visit: https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/understanding-hiv-aids/fact-sheets/21/54/hiv-medication-adherence

Relatedly, a publication by the National Stroke Association states that poor medication adherence can lead to unnecessary disease progression and complications, lower quality of life, reduction in one’s abilities, additional medical costs per year, the need for more specialized and expensive medical resources, lengthy hospital stays, and unneeded changes to one’s medication. They offer suggestions for improving adherence to include:

- Talk to your physician about your unique needs or health status.

- Explore the use of generics to remove the cost barrier.

- Form good habits such as taking your medications at the same time every day.

- Advocate for yourself. Learn about your condition and the medications you are taking.

- Use one pharmacy to fill your prescriptions.

- Use reminders, or as we called them in Module 6, prompts and/or antecedent manipulations, to remember when to take your medications.

- Track your medications as to when and how you take/took them.

11.4. Motivated by Pain Relief

Section Learning Objectives

- Define pain.

- Contrast acute and chronic pain.

- Describe the experience of pain.

- Outline solutions for dealing with pain.

- Determine the prognosis for acute and chronic pain.

According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, pain is “a sharp unpleasant sensation usually felt in some specific part of the body” and is also described as discomfort, soreness, tenderness, inflammation, being hurt, or suffering. (Source: https://www.merriam-webster.com/thesaurus/pain). Pain has two main types. First, acute pain is brief, begins suddenly, has a clear source, and is adaptive. If we touch a hot iron, the pain we experience would be classified as acute and lets us know that we may need to act to deal with the damage currently done, but also to avoid further damage or injury. Acute pain signals danger.

In contrast, chronic pain lasts for a long period of time and up to months or years, is fleeting (it comes and goes), disrupts normal patterns such as sleep and appetite, and is the result of a disease or injury. Unlike acute pain, chronic pain is not adaptive. Examples include arthritis, a broken arm, back problems, migraines, or cancer. It can feel like throbbing, stiffness, burning, shooting, or a dull ache.

How we experience pain is as unique as our personality. It is a subjective experience and two people could experience the same wound and have two totally different interpretations. Consider the simple paper cut. For some the pain could be excruciating while for others it goes unnoticed. Okay. This may be a bit of a stretch, but you get the point. Are there gender differences in pain perception? Most of us would say that there are but what is the source of this difference? Could it be that the body deals with pain differently for men and women and so these differences represent true biological variation? Research does not support this idea as few gender differences have been found in the detection threshold for most types of pain (Racine et al., 2012). Now consider that boys are often taught to ignore pain while girls are taught that it is okay to acknowledge pain. This shows that gender differences in pain perception are socially constructed through gender roles (Pool et al., 2007).

Pain is not a pleasant experience, whether acute or chronic, so what do we do to deal with it? The obvious answer is to obtain medication. Painkillers or analgesics can deal with most types of pain and include drugs such as Tylenol, Advil, Motrin, and Aleve. They act by interfering with pain messages or by reducing inflammation and swelling which make the pain worse. Morphine and codeine are powerful pain relievers which fall under the classification of narcotics but are risky to take due to their addictive properties and side effects.

Of course, if drugs are not the answer surgery may be necessary. Surgical implants can be used to control the pain and take the form of infusion pain pumps or spinal cord stimulation implants. In the case of the former, a pump is installed in a small pocket under the skin with a catheter that carries pain medicine from the pump to the intrathecal space around the spinal cord, or to where pain signals travel. In the case of the latter, low-level electrical signals are sent to the spinal cord or specific nerves from a device surgically implanted in the body to inhibit the transmission of pain signals. The patient turns the current on or off and adjusts its intensity via a remote control. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation therapy, also called TENS, can be used to deliver a low-voltage electrical current via electrodes on the skin and near the site of the pain and scrambles normal pain signals. Finally, bioelectric therapy provides pain relief by causing the body to produce endorphins that block the delivery of pain messages to the brain.

Outside of drugs and surgery, pain can be reduced through massage therapy, acupuncture, psychotherapy, and relaxation training such as progressive muscle relaxation or the tensing and relaxing of muscle groups throughout the body. Behavior modification procedures mentioned in Module 6 can be useful also.

The prognosis for acute pain is good and drugs can provide effective pain relief. Since the cause is generally identifiable, removing this source alleviates the pain. Chronic pain is a bit trickier as the source is not clear and so effective coping mechanisms may need to be implemented to include nondrug or surgery options, managing stress, exercise to boost natural endorphins, joining a support group, and changing one’s lifestyle. It is even a good idea to track pain levels and your activities daily to see which activities might reduce or aggravate your pain and then share this information with your doctor.

For more on pain and its management, please see WebMD:

https://www.webmd.com/pain-management/guide/pain-management-treatment-overview#3-6

11.5. Pursuing Alternative Forms of Medical Care

Section Learning Objectives

- Describe types of CAMs individuals can use.

According to the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) which is part of the National Institutes of Health, about 30% of adults and 12% of children pursue health care options outside of traditional Western medicine. These approaches can be complementary meaning they are used in conjunction with conventional medicine, or alternative, meaning they are used in place of Western medicine (take note of the term CAM standing for complementary and alternative medicines). Most though, pursue complementary methods which can include:

- Use of Natural Products – This includes herbs, probiotics, and vitamins.

- Mind and Body Practices – This includes massage therapy, visiting a chiropractor, yoga, acupuncture, relaxation techniques, and meditation.

- Other Approaches – This includes traditional healers, Ayurvedic medicine, traditional Chinese medicine, homeopathy, and naturopathy

Source: https://nccih.nih.gov/health/integrative-health

NCCIH’s website includes a wealth of information on the topic of alternative medicine to include:

- Are You Considering a Complementary Health Approach? – https://nccih.nih.gov/health/decisions/consideringcam.htm

- Children and the Use of Complementary Health Approaches – https://nccih.nih.gov/health/children

- 5 Tips: What Consumers Need to Know About Dietary Supplements – https://nccih.nih.gov/health/tips/supplements

- Safe Use of Complementary Health Products and Practices – https://nccih.nih.gov/health/safety

- 6 Things to Know When Selecting a Complementary Health Practitioner – https://nccih.nih.gov/health/tips/selecting

- Herbs at a Glance – https://nccih.nih.gov/health/herbsataglance.htm

- Research on CAMs – https://nccih.nih.gov/research/results

- Ayurvedic medicine – https://nccih.nih.gov/health/ayurveda/introduction.htm

- Traditional Chinese medicine – https://nccih.nih.gov/health/whatiscam/chinesemed.htm

- Homeopathy – https://nccih.nih.gov/health/homeopathy

- Naturopathy – https://nccih.nih.gov/health/naturopathy

The American Cancer Society publishes a guide for cancer treatments falling under CAMs – https://www.cancer.org/treatment/treatments-and-side-effects/complementary-and-alternative-medicine.html

Module Recap

That’s it for Module 11. Remember, a comprehensive discussion of health psychology was not possible given page and time constraints, but the point was to provide you with an overview of how we might be motivated to engage in health promoting behaviors. In Module 15 we will discuss specific health behaviors and how we are motivated for better or worse. Also, in Module 4 we saw how stress can wreak havoc on our health, so we have, and will, tackle this issue throughout the book.

For now, we discussed the dimensions of wellness, our motivation to see the doctor or seek health information, whether we adhere to doctor’s orders, how we manage pain, and finally, a brief outline of CAMs was presented with numerous resources to examine if you desire to learn more.

We have just one module left in Unit IV which deals with social psychology.

2nd edition