Module 5: The Costs of Motivated Behavior

Module Overview

For motivated behavior to occur certain costs must be paid and we need to have the resources to cover them. If you go to the store to buy the latest movie or a CD, these products cost money. Assume a movie costs $20. When we go to pay the cashier, we present our bank card. In order for us to leave the store the proud owner of the latest and greatest, we must have sufficient funds in our checking account. If this condition is not met, meaning we do not have enough resources, our transaction is declined, we face potential embarrassment, and leave the store without the movie. Module 5 will show how costs relate to motivated behavior. We will also discuss how we are motivated to engage in the least effort possible for the same return on our behavior.

Module Outline

- 5.1. Expanding Our Model

- 5.2. Costs of Motivated Behavior

- 5.3. Resources to Cover the Costs

- 5.4. Least Effort

Module Learning Outcomes

- Clarify how costs relate to motivated behavior.

- Explain the concept of the economics of motivated behavior.

- List and explain the five costs of motivated behavior.

- List and explain resources used to pay for motivated behavior.

- Define the principle of least effort.

5.1. Expanding our Model

Section Learning Objectives

- Clarify the importance of costs in the stress and coping model and other forms of motivated behavior.

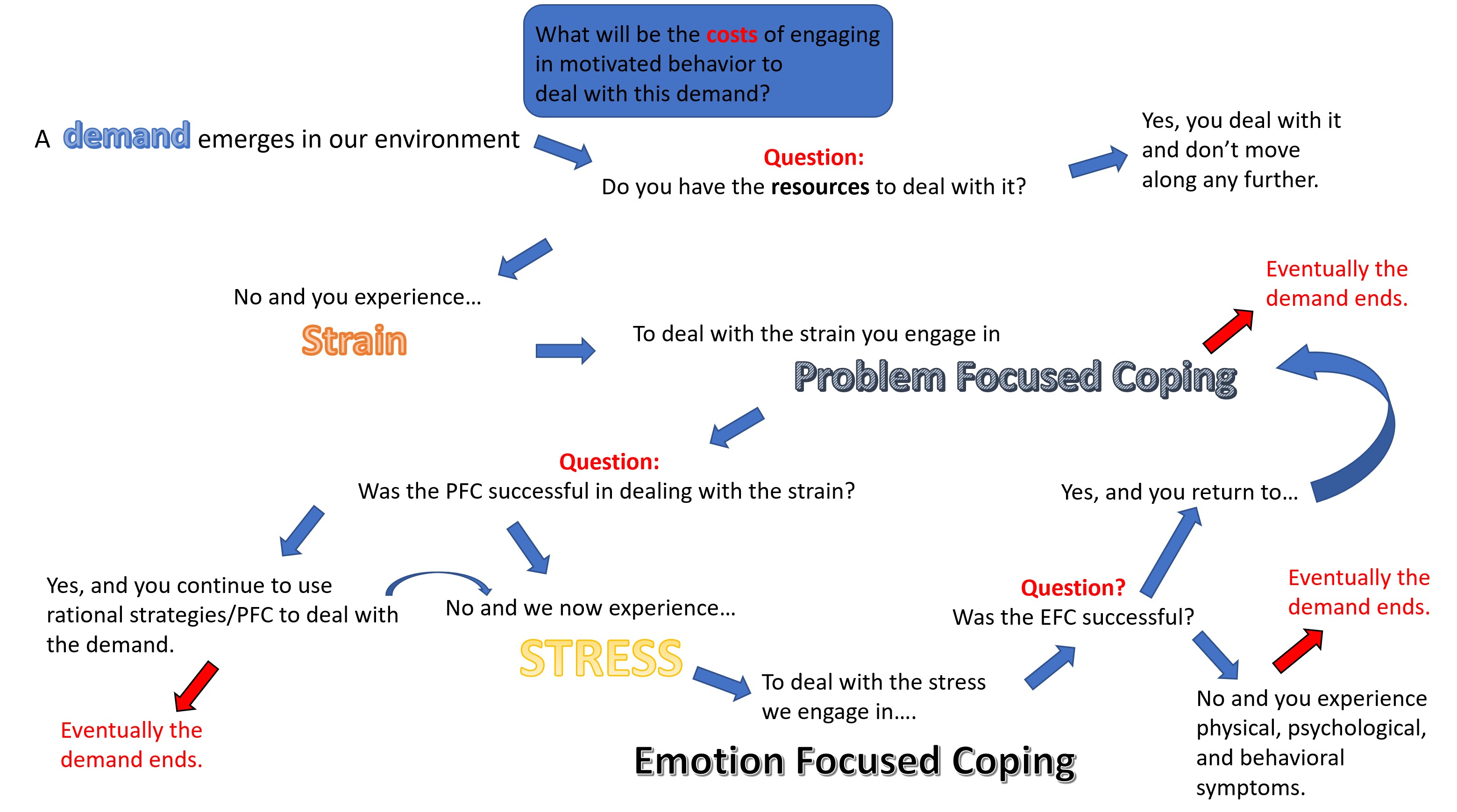

Figure 5.1. Expanded Stress and Coping Model

In Module 4, I presented the stress and coping model as displayed above. I also indicated that I would expand upon it in Module 5. Notice in the figure the presence of the blue box at the top. When a demand presents itself in our environment, we assess our resources, but to know which resources we need, we must first know what the costs are of engaging in the motivated behavior. In the case of the information presented in Module 4, these costs are associated with engaging in actions to deal with the demand as it first appears. At this stage, we have only sensed the stimuli from our environment, determined it to be a threat, and then, began to figure out a rational plan to deal with it (the processes of sensation, perception, and primary and secondary appraisal). Part of our efforts at secondary appraisal are determining what we need to deal with the issue. If it is a paper, our costs of motivated behavior likely include time and psychological energy. Do we have the resources to cover the costs? I am sitting to write this module and know that though it is not a long one, it will likely take me about 3 hours to complete. This is the cost – 3 hours of my precious time. My resources show me that since it is 8:30 am now and I have until about 4:30 pm to work today, I have approximately 8 hours of time to dedicate to this endeavor. I need about 3 hours. I have 8 hours of time. The math shows that I have another 5 hours more than I may need. That’s good because I often misjudge how long a module will take to write and need another hour or so. I know that I have 5 hours beyond the 3 I have budgeted and if a fourth hour is needed, I am good. And I still have time for other tasks.

I don’t want to give you the impression that costs and resources only are involved when we are dealing with a demand. They apply in all situations where motivated behavior is needed. Outside of responding to a demand in our environment, we might decide to pick up a book to read. This is another type of motivated behavior that may not be linked to a demand, such as having to read the chapter for class tomorrow. Maybe it is bedtime and we want to continue reading Harry Potter: The Order of the Phoenix for our own personal enjoyment and not because of a demand from a professor. The costs of engaging in the motivated behavior of reading for pleasure are about 30 minutes of time and having to dedicate our attention to the task. The costs would be about the same if the motivation for reading was driven by an external source and our professor, and not an internal source and our need to disengage from everyday life and immerse ourselves in a fantasy world. I believe Harry and You-Know-Who would agree.

5.2. Costs of Motivated Behavior

Section Learning Objectives

- Clarify the effect of response costs on motivated behavior.

- Clarify how time serves as a cost of motivated behavior.

- Describe the need for physical energy in motivated behavior.

- Describe the need for psychological energy in motivated behavior.

- Clarify how opportunity costs lead to regret where motivated behavior is concerned.

Now that we understand that costs are involved where motivated behavior is concerned, and that resources are used to pay them, it’s time to outline some of these costs.

First, response costs involve any behaviors that need to be made to achieve a goal. Think back to when you had your introductory psychology course. In it, you learned about reinforcement schedules. Fixed Ratio (FR) and Variable Ratio (VR) schedules both involve making a response/behavior and then being reinforced for it. Fixed means that you are reinforced according to a schedule, say every 5 responses you receive a food pellet (that is, if you are a lab rat). Variable indicates some varying number of responses need to be made before reinforcement occurs. Slot machines are great examples of VR schedules. The response is pulling the handle and after some varying number of times doing that, you, or the lucky person after you, wins! FR and VR schedules exemplify responses costs. We are motivated to engage in a behavior because of the reinforcement that follows (i.e., the goal is winning or receiving food).

Second, time is a cost that plagues most of us. We need time to write a paper. No problem. Oh wait. We have to take care of the kids, study for an exam, write another paper, read for each class, go to work, etc…. Where did all the time go? Jobs are a great example of time costs too. Some amount of time must pass before we are paid for doing what we were hired to do. In relation to the discussion of reinforcement schedules above, time is on an interval schedule and for most of us, we are paid according to a Fixed Interval (FI) schedule, usually every Friday or every two weeks. We are motivated to go to work and do our job to receive our paycheck on this regular basis. What happens if our employer stops paying us? Well, you know the answer to that.

Most motivated behavior requires the expenditure of physical energy in the form of calories and glucose. The calorie serves as a measure of energy, similar to a pound being a measure of weight or the minute being a measure of time. When we engage in motivated behavior, we exert or spend these energy reserves. For instance, at my current age, height, and weight, if I brush my teeth for 5 minutes, I will burn approximately 28 calories. I have to mow the lawn later today and estimate that it will take about 30 minutes to do so. Engaging in this motivated behavior will burn approximately 292 calories. Check out how many calories you burn during different activities by visiting: https://www.healthstatus.com/calculate/cbc/. Keep in mind that intensity factors in too. The calculator just asks about duration.

When we engage in mental work, we expend glucose. Glucose is a monosaccharide or a simple sugar, the same as fructose or ribose, and is one of the body’s preferred sources of fuel along with fat. The brain is an especially energy-demanding organ and uses half of all sugar energy in the body for functions such as learning, memory, and decision making. When glucose levels in the brain are insufficient, neural transmission breaks down and we might experience reduced cognitive function and issues maintaining our attention. As too little glucose is bad, too much can be too, and has been linked to memory and cognitive deficiencies.

Outside of this type of energy, we also need psychological energy in terms of dedication to the goal, sustained attention, planning, and self-control. Consider your motivated behavior of reading this module. Your goal is to finish reading the entire module and you also likely set aside some time to do so. Maybe you chose the time you did because you knew your kids would be at school or taking a nap or your roommate was going to be out of the dorm for a few hours. By having this dedicated time, you almost guaranteed yourself quiet so you can focus your attention more effectively. This also represents careful planning. What about self-control? Well, you surely will want to check your phone, email, play a game, or watch a YouTube video during the reading time but keep yourself from doing so. You exert self-control or will power and avoid engaging in these distracting tasks. Thanks to having sufficient psychological energy, you finish reading the module (or will soon) and feel accomplished for the day. In Module 4 we also talked about adaption energy which is another form of psychological energy. Recall that this is the energy needed to deal with change. As long as we have enough of it, we handle demands fine. When it runs out, we become exhausted and experience the physical, psychological, and behavioral effects of stress. So how much adaptation energy do we need, and do we have enough of it in the moment?

Finally, writing a paper takes time away from other activities we might rather be doing, such as playing with the kids or putting in time on Call of Duty. These lost endeavors are called opportunity costs. Reading this module means you are not working on a paper, studying for a test, hanging out with friends, or doing some other task. This might lead to a feeling of regret for passing up these other activities. Researchers have found that the more choices you have, the greater the regret. Haynes (2009) presented participants with descriptions of 3 to 10 prizes and asked them to choose one to be entered into a drawing. Participants were also given a limited or extended amount of time to make their decision. Those given a limited time with many choices were frustrated and found the task to be difficult. Having more choices led participants to feel less satisfaction but not less regret with their decision. This is called choice overload phenomenon. Sagi and Friedland (2007) found that regret was magnified if people ruminated on the other options and how much satisfaction they may have gained from them. In terms of opportunity costs, if our friends are preoccupied for the night and there is nothing on television to watch, then we will feel less regret having to read this module since there are fewer missed opportunities to serve as costs of our motivated behavior. If there are numerous other tasks we could be engaging in (i.e., choices), then our regret will be higher, and could lead us to be unmotivated to read.

Now that we have covered the five main costs of motivated behavior, are there others that you would include? Consider money as one. You are a student engaging in motivated behavior daily, all geared at achieving the distal goal of earning your bachelor’s degree. This creates stress for you, which you manage using both problem and emotion focused coping strategies and rely on your peers as a form of social support. The degree will be worth it in the end, but how long will you have to pay your student loans off, if you had to take them? In terms of the goal of getting the degree, you face one key cost – money. Student loans, using your savings account, or just paying out of pocket each semester, represents the resources used to pay the bill/cost for your education.

Are there other costs we can add to the list?

5.3. Resources to Cover the Costs

Section Learning Objectives

- Clarify the role of resources in relation to costs.

- List and describe some of the resources to cover the costs of motivated behavior.

To engage in any motivated behavior, we have specific costs for which we need resources to cover them. Like the CD we wish to purchase at the department store, we must have the required resources. If it is $15.99, we need at least that much in our wallet or checking account. If we do not have it, we cannot make the purchase and walk out empty handed. This economic model is exactly what paying for the costs of motivated behavior is like, but we need resources beyond just money. So, what resources do we have?

First, response resources are the number of behaviors necessary to complete a goal. If your goal is to build a garden so you can plant strawberries, how many times will you need to push a shovel into the ground, lift out the dirt, and move it to another pile. If the answer is 100 times (the cost), then do you have the ability to make those 100 repetitive responses or engaging in this motivated behavior that many times (the resource)? If you are paid to complete surveys online, the pointing and clicking with your mouse while doing the survey are the responses necessary to complete the task.

Next are physical energy resources. Do you have enough energy/glucose so you can burn the calories necessary to build the garden or help you focus your attention on reading this module? Physical energy resources are especially problematic for a diabetic since their body is unable to convert sugar into energy, which leads to feeling worn down or being extremely exhausted. Motivated behavior under these circumstances is almost impossible.

The third resource is psychological energy resources. How much self-control or self-regulation energy (Baumeister et al., 1998) do you have or are you impulsive in nature and act on a whim? Do you have enough adaptation energy (Selye, 1976) to deal with the demands you face as a student?

Finally, grit is a term coined by Duckworth, Peterson, and Matthews (2007) and states that to achieve difficult goals, we need more than just talent and opportunity, but the ability to focus and persevere over time. According to a 2013 Forbes article, grit has five main characteristics: the courage to manage your fear of failure, being achievement oriented and dependable or committing to “go for the fold rather than just show up for practice,” follow through with your long-term goals, being optimistic and knowing that things will work themselves out in the end, and not seeking perfection but striving for excellence. You might be wondering if self-control and grit are related to one another. They are related but also distinct terms. Self-control involves engaging in one activity while resisting the urge to partake in more-alluring alternatives while grit is passion and effort that are sustained over a long period of time. In relation to goals, Duckworth and Gross (2014) writes, “Self-control is required to adjudicate between lower-level goals entailing necessarily conflicting actions. One cannot eat one’s cake and have it later, too. In contrast, grit entails maintaining allegiance to a highest-level goal over long stretches of time and in the face of disappointments and setbacks.”

- Check out the Forbes article on Grit at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/margaretperlis/2013/10/29/5-characteristics-of-grit-what-it-is-why-you-need-it-and-do-you-have-it/#79163d2d4f7b.

- Also, Duckworth talks about Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance on this Ted Talk: https://www.ted.com/talks/angela_lee_duckworth_grit_the_power_of_passion_and_perseverance?utm_campaign=tedspread&utm_medium=referral&utm_source=tedcomshare

Before we move on, there appears to be a misunderstanding where costs and resources are concerned and that the terms are interchangeable. They are not. Consider this. Physical energy is one cost of a motivated behavior, such as working out at the gym. To do our workout, we need to have a specific amount of glucose in our blood, or the workout ends pretty quickly. This amount is the cost. How much we have on hand at the time is the resource. If we have as much or more than the predicted cost, we have enough to do the workout. If it is less than this amount, we cannot sustain the workout. Again, its as simple as the CD example given at the beginning of this section.

5.4. Least Effort

Section Learning Objectives

- Define and exemplify principle of least effort.

For many of our goals or motivated behaviors, the costs can be high, and our resources tapped. As such, human beings are motivated to invest the least effort necessary to complete these goals. Tolman (1932) called this the principle of least effort meaning that when a person can choose between two incentives which have approximately the same incentive value, they will choose the one that is easiest to achieve or that requires the least amount of effort. Like rats in a maze, we choose the shortest route to the goal box if a food pellet has been placed there. Think about your distal goal of obtaining your bachelor’s degree. Of course, you need to take classes in your major and for many of you, this route is pre-determined by your department. But the university requires you to also take electives and you have some degree of freedom to choose classes that interest you. Have you ever filled your schedule with classes known to be easy and require little effort to pass? If you have, you exercised the principle of least effort. Why not? A credit is a credit, right? If you take a difficult elective and pass the course, you earn the same three credits that you would if you took an easy class. So maybe you are best expending your limited number of resources on the courses that matter most for your career down the line and save on other classes that may not be as useful. This seems like a logical strategy!

Research has shown that if given the opportunity to save energy, people will take it but that this can have a negative impact on our health such that we need to target and change these automatic associative processes (Marteau, Hollands, & Fletcher, 2012). The authors suggest making the elevator less appealing than taking the stairs by increasing the effort needed to use it, making healthier options on a salad bar easier to reach than unhealthy ones, and making it harder to get to stores which sell alcohol, tobacco, and junk food. In a way, I suppose they are not suggesting we find ways to change this way of thinking, but to use it to our advantage so that people engage in health promoting behaviors naturally, as part of least effort.

Module Recap

Setting goals, dealing with demands, and engaging in motivated behavior comes at a cost to us and we need to make sure we have the resources to cover it. Do you have enough time to write two papers and study for a test, all while doing homework for other classes and working? What opportunities are you missing out on? How much physical and psychological energy will be required? What behaviors do you need to make? How good are your resources to cover these costs? If they are inadequate, you experience strain and need to develop strategies to find new sources of time, energy, or responses. But no matter what you are doing, you are constantly motivated to put in the least amount of effort to achieve the goal. Why spend three hours studying for an exam if you can study one hour and obtain the same grade? This generally works but can backfire on us at times.

2nd edition