Module 15: Motivation, for Better and Worse

Module Overview

At last, we make it to the final module in the book. Over the past 14 modules I have laid a framework for understanding motivated behavior by discussing basic ideas in motivation, emotion, goals, stress and coping, economics, personality, and needs. We began the process of applying this knowledge by discussing behavior modification, religious behavior, development, health and wellness, social processes, cognition and memory, and issues related to physiological processes. In Module 15 we will continue to apply what we have learned but in terms of types of motivated behavior that lead to positive ends and those that lead to negative ends. I call this motivation for better and motivation for worse. Topics not covered in this book so far, or at least minimally, will be introduced to include understanding normal and abnormal behavior; love and jealousy; social facilitation and social loafing; social influence and its three forms of compliance, conformity, and obedience; helping behavior; forgiveness; health promoting and defeating behaviors; prejudice and discrimination; mob behavior; and the stigmatization of mental disorders. Once this is complete, and it is a tall order to fill, we will focus on a possible explanation that underlies all these behaviors and many covered in the book so far – universal human values. This module is really meant to tie up loose ends, introduce new topics taught in various psychology courses, and propose a new way of understanding motivated behavior. I hope you enjoy it.

Module Outline

- 15.1. Motivation, for Better

- 15.2. Motivation, for Worse

- 15.3. Explaining Behavior, For Better or Worse, Through Values

Module Learning Outcomes

- Outline ways in which we engage in motivated behavior for the betterment of ourselves and others.

- Outline ways in which we engage in motivated behavior to the detriment of ourselves and others.

- Argue for values as a high-level explanation for the behaviors presented in this module and all preceding ones.

15.1. Motivation, for Better

Section Learning Objectives

- Explain why exercise is a type of motivated behavior for the better.

- Propose a way to understand what normal behavior is through positive psychology.

- Explain why love is a type of motivated behavior for the better.

- Explain why social facilitation is a type of motivated behavior for the better.

- Explain why helping behavior is a type of motivated behavior for the better.

- Explain why forgiveness is a type of motivated behavior for the better.

- Explain why compliance is a type of motivated behavior for the better.

- Explain why conformity is a type of motivated behavior for the better.

15.1.1. Health Promoting Behaviors – Exercise

If you are going to engage in any health promoting behavior, exercise is a way to get a lot of bang for your buck. It has tremendous benefits to include weight loss, reducing the risk of heart diseases, improving mood, managing blood sugar and insulin levels, strengthening bones and muscles, reducing the risk of some cancers such as colon and lung, improving sleep, improving sexual health, buffering against the effects of stress, and quite possibly most important, it can help us living longer (https://medlineplus.gov/benefitsofexercise.html).

Exercise takes several different forms. First, endurance or aerobic exercise increases our breathing and heart rate over an extended period. It can include going for a walk after dinner, swimming, going for a run outside or on the treadmill, and using an elliptical. In contrast, anerobic exercise involves no additional oxygen consumption since energy is expelled in short, intensive bursts such as playing baseball or short distance running. Second, strength or resistance training, also called isotonic exercise, involves lifting weights with the intention of making your muscles stronger. Third, balance exercises help with walking on uneven surfaces and can reduce falls. Balance exercises can include tai chi or standing on one leg. Finally, flexibility involves stretching muscles, which aid in staying limber.

So how do you make exercise a part of your daily routine? Medline Plus suggests making everyday activities more active. Instead of taking the elevator or escalator, use the stairs. You should also exercise with others such as family and friends. The site states, “Having a workout partner may make you more likely to enjoy exercise. You can also plan social activities that involve exercise. You might also consider joining an exercise group or class, such as a dance class, hiking club, or volleyball team.” You should also listen to music, watch television, or try new machines and exercises to make working out more fun. Track your progress so that you can see how you much you are improving and to stay motivated. Finally, finding activities to do when the weather is bad is recommended.

Of course, exercising does come with its risks. Injuries and soreness are possible, but most people accept them. If you exercise safely and use proper equipment, you can avoid or minimize these negative consequences. It is good to listen to our body and not overdo it. Exercise addiction is another possibility and is when a person shows a strong emotional attachment to exercise (Ackard, Brehm, & Steffen, 2002). Withdrawal symptoms such as depression and anxiety occur if the person is prevented from working out.

For more on exercising and physical fitness, please visit:

- https://medlineplus.gov/exerciseandphysicalfitness.html

- https://familydoctor.org/the-exercise-habit/?adfree=true

15.1.2. Understanding Normal Behavior

Any understanding of normal behavior is in the eye of the beholder and most psychologists have found it easier to explain what is wrong with people than what is right. How so?

Psychology worked with the disease model for over 60 years, from about the late 1800s into the middle part of the 20th century. The focus was simple – curing mental disorders – and included such pioneers as Freud, Adler, Klein, Jung, and Erickson. These names are synonymous with the psychoanalytical school of thought. In the 1930s, behaviorism, under B.F. Skinner, presented a new view of human behavior. Simply, human behavior could be modified if the correct combination of reinforcements and punishments were used. This viewpoint espoused the dominant worldview still present at the time – mechanism – and that the world could be seen as a great machine and explained through the principles of physics and chemistry. In it, human beings were smaller machines in the larger machine of the universe.

Moving into the mid to late 1900s, we developed a more scientific investigation of mental illness which allowed us to examine the roles of both nature and nurture and to develop drug and psychological treatments to “make miserable people less miserable.” Though this was good, there were three consequences as pointed out by Martin Seligman in his 2008 TED Talk entitled, “The new era of positive psychology.” These are:

- “The first was moral; that psychologists and psychiatrists became victimologists, pathologizers; that our view of human nature was that if you were in trouble, bricks fell on you. And we forgot that people made choices and decisions. We forgot responsibility. That was the first cost.”

- “The second cost was that we forgot about you people. We forgot about improving normal lives. We forgot about a mission to make relatively untroubled people happier, more fulfilled, more productive. And “genius,” “high-talent,” became a dirty word. No one works on that.”

- “And the third problem about the disease model is, in our rush to do something about people in trouble, in our rush to do something about repairing damage, it never occurred to us to develop interventions to make people happier — positive interventions.”

One attempt to address the limitations of both psychoanalysis and behaviorism came from 3rd force psychology – humanistic psychology – under such figures as Abraham Maslow and Carl Rogers starting in the 1960s. As Maslow said, “The science of psychology has been far more successful on the negative than on the positive side; it has revealed to us much about man’s shortcomings, his illnesses, his sins, but little about his potentialities, his virtues, his achievable aspirations, or his full psychological height. It is as if psychology had voluntarily restricted itself to only half its rightful jurisdiction, and that the darker, meaner half (Maslow, 1954, p. 354).” Humanistic psychology instead addressed the full range of human functioning and focused on personal fulfillment, valuing feelings over intellect, hedonism, a belief in human perfectibility, emphasis on the present, self-disclosure, self-actualization, positive regard, client centered therapy, and the hierarchy of needs. Again, these topics were in stark contrast to much of the work being done in the field of psychology up to and at this time.

In 1996, Martin Seligman became the president of the American Psychological Association (APA) and called for a positive psychology or one that had a more positive conception of human potential and nature. Building on Maslow and Roger’s work, he ushered in the scientific study of such topics as happiness, love, hope, optimism, life satisfaction, goal setting, leisure, and subjective well-being. Though positive and humanistic psychology have similarities, it should be pointed out their methodology was much different. While humanistic psychology generally relied on qualitative methods, positive psychology utilizes a quantitative approach and aims to make the most out of life’s setbacks, relate well to others, find fulfillment in creativity, and finally help people to find lasting meaning and satisfaction.

For more on positive psychology, please visit:

https://www.positivepsychologyinstitute.com.au/what-is-positive-psychology)

So, to understand what normal behavior is, do we look to positive psychology for an indication, or do we first define abnormal behavior and then reverse engineer a definition of what normal is? Our preceding discussion gave suggestions about what normal behavior is, but could the darker elements of our personality also make up what is normal, to some extent? Possibly. The one truth is that no matter what behavior we display, if taken to the extreme, it can become disordered – whether trying to control others through social influence or helping people in an altruistic fashion. As such, we can consider abnormal behavior to be a combination of personal distress, psychological dysfunction, deviance from social norms, dangerousness to self and others, and costliness to society. More on this in Section 15.2.2.

15.1.3. Love

In Section 12.3 we discussed interpersonal attraction. One outcome of this attraction to others, or the need to affiliate/belong (Section 8.2) is love. What is love? According to a 2011 article in Psychology Today entitled, ‘What is Love, and What Isn’t It?,’ love is a force of nature, is bigger than we are, inherently free, cannot be turned on as a reward or off as a punishment, cannot be bought, cannot be sold, and cares what becomes of us (Source: https://www.psychologytoday.com/intl/blog/love-without-limits/201111/what-is-love-and-what-isnt). Adrian Catron writes in an article entitled, “What is Love? A Philosophy of Life” that “the word love is used as an expression of affection towards someone else….and expresses a human virtue that is based on compassion, affection and kindness.” He goes on to say that love is a practice, and you can practice it for the rest of your life” (Source: https://www.huffpost.com/entry/what-is-love-a-philosophy_b_5697322). And finally, the Merriam Webster dictionary online defines love as “strong affection for another arising out of kinship or personal ties” and “attraction based on sexual desire: affection and tenderness felt by lovers” (Source: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/love).

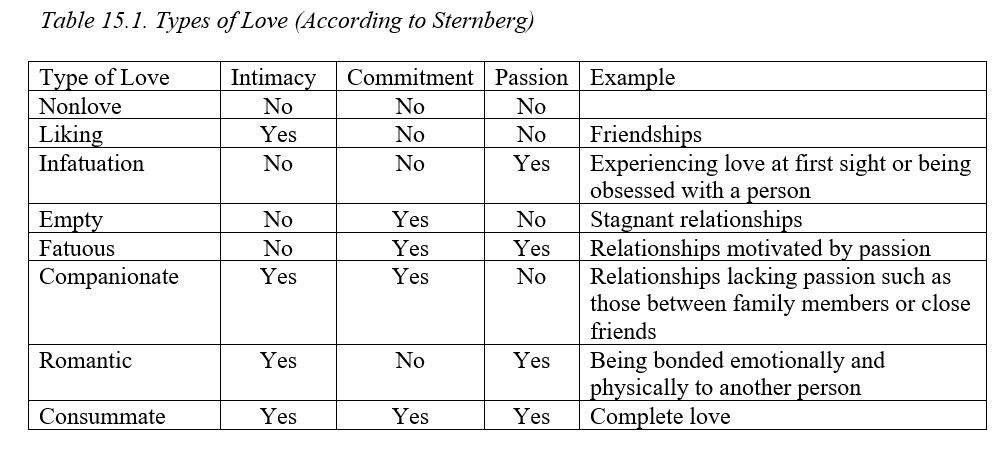

Robert Sternberg (1986) said love is composed of three main parts (called the triangular theory of love): intimacy, commitment, and passion. First, intimacy is the emotional component and involves how much we like, feel close to, and are connected to another person. It grows steadily at first, slows down, and then levels off. Features include holding the person in high regard, sharing personal affects with them, and giving them emotional support in times of need. Second, commitment is the cognitive component and occurs when you decide you truly love the person. You decide to make a long-term commitment to them and as you might expect, is almost non-existent when a relationship begins and is the last to develop usually. If a relationship fails, commitment will show a pattern of declining over time and eventually returns to zero. Third, passion represents the motivational component of love and is the first of the three to develop. It involves attraction, romance, and sex and if a relationship ends, passion can fall to negative levels as the person copes with the loss.

This results in eight subtypes of love which explains differences in the types of love we express. For instance, the love we feel for our significant other will be different than the love we feel for a neighbor or coworker, and reflect different aspects of the components of intimacy, commitment, and passion as follows:

15.1.4. Social Facilitation

Have you ever noticed that when you go to the gym you workout harder if someone else is with you (i.e., a workout buddy), but you don’t necessarily put in the same effort if alone? This is called social facilitation and is when the presence of other people affects our performance depending on the type of task. Zajonc (1965, 1980) said that performance increases across three steps, starting with the presence of others causing a rise in our physiological arousal which motivates our behavior. This allows us to make what he called the dominant response, or the reaction that follows the quickest and easiest from a stimulus. Whether this response is accurate or not depends on how difficult the task is. The dominant response is usually the correct one for easy tasks but not necessarily for difficult tasks. Think about when you study for an upcoming exam for the first time. If a fellow classmate quizzes you, your arousal will increase and strengthen the dominant response. But your performance will go down since the material being studied is new at this point and you have not had a chance to really understand it and commit it to memory. What about five days later, after studying tirelessly for the exam, and an hour before the exam? How might this classmate’s quizzing (or presence) affect your performance? As before you are aroused, making the dominant response, but this time your performance is much better as the task is now easy for you. I predict you will satisfy your achievement motivation by earning a high grade on the exam.

15.1.5. Helping Behavior

When do you help others? Do you lend assistance in every situation or are you more likely to help in some situations than others? We might engage in this type of motivated behavior because we really want to help others, called altruistic behavior. We expect nothing in return or have no expectation of reciprocation. Or we might help someone because we expect that in the future, when we are facing a similar situation, they will help us, called reciprocal altruism (Krebs, 1987). If we help a friend move into their new apartment, we expect help from this individual when we move next time. Or we might help with an expectation of a specific form of repayment, called perceived self-interest. We offer our boss a ride home because we believe he will give us a higher raise when our annual review comes up.

Attribution theory says there are factors in the situation and those in the person that affect helping behavior (See Section 12.1 if you need to refresh your memory on this). In terms of the latter, if we sense greater personal responsibility, we will be more likely to help such as there being no one else around but us. If we see a motorist stranded on an isolated country road, and we know no other vehicle is behind us or approaching, responsibility solely falls on us and we will be more likely to help. We might also help because we have a need for approval such as we realize by helping save the old lady from the burning building, we could get our name in the paper. Mood, our topic in Module 2, plays in too. Do you think we will be more likely to help when in a good or bad mood? If you said good mood, you are correct. Think about a bad mood and the cliché ‘Misery loves company.’ My wife has a great expression she uses when in a bad mood to illustrate this – ‘Sucks to be you.’ In a good mood, she will move heaven and earth to help someone. Finally, we will be more likely to help if we don’t expect to experience any type of embarrassment when helping. Let’s say you stop to help a fellow motorist with a flat tire. If you are highly competent at changing tires (see Module 1) then you will not worry about being embarrassed. But if you know nothing about tires and are highly attracted to the stranger on the side of the road holding a tire iron with a dumbstruck look on his or her face, you likely will look foolish if you try to change the tire and demonstrate your ignorance of how to do it (your usual solution is usually to call AAA when faced with the same stressor). These are some dispositional reasons why we may or may not help.

What about situational factors? As we saw above, if we are the only one on the scene (or at least one of a few) we will feel personal responsibility and help. But what if we are among a large group of people who could help? Will you step up then? You still might, but the bystander effect (Latane & Darley, 1970) says likely not. Essentially, the likelihood that we will aid someone needing help decreases as the number of bystanders increases. The phenomenon draws its name from the murder of Ms. Kitty Genovese in March 1964. Thirty-eight residents of New York City failed to aid the 24-year-old woman who was attacked and stabbed twice by Winston Moseley as she walked to her building from her car. Not surprisingly, she called for help, which did successfully scare Winston away, but when no one came out to help her, despite turning on lights in their apartments and looking outside, he returned to finish what he started. Ms. Genovese later died from her wounds. Very sad, but ask yourself, what would you do? Of course, we would say we would help….or we hope that we would, but history and research say otherwise. Another situational factor is ambiguity. Let’s say you are driving down the road and see someone pulled over on the side. You can see them in the front seat but cannot tell what they are doing. If the situation does not clearly suggest an emergency, you will likely keep driving. Maybe the person was acting responsibly and pulled over to send a text or take a call and is not in need of any assistance at all.

15.1.6. Forgiveness

According to the Mayo Clinic, forgiveness involves letting go of resentment and any thought we might have about getting revenge on someone for past wrongdoing. So, what are the benefits of forgiving others? Our mental health will be better, we will experience less anxiety and stress, we may experience fewer symptoms of depression, our heart will be healthier, we will feel less hostility, and our relationships overall will be healthier.

It’s easy to hold a grudge. Let’s face it, whatever the cause, it likely left us feeling angry, confused, and sad. We may even be bitter not only to the person who slighted us but extend this to others who had nothing to do with the situation. We might have trouble focusing on the present as we dwell on the past and feel like life lacks meaning and purpose.

But even if we are the type of person who holds grudges, we can learn to forgive. The Mayo Clinic offers some useful steps to help us get there. First, we should recognize the value of forgiveness. Next, we should determine what needs healing and who we should forgive and for what. Then we should consider joining a support group or talk with a counselor. Fourth, we need to acknowledge our emotions, the harm they do to us, and how they affect our behavior. We then attempt to release them. Fifth, choose to forgive the person who offended us leading to the final step of moving away from seeing ourselves as the victim and “release the control and power the offending person and situation have had in your life.”

At times, we still cannot forgive the person. They recommend practicing empathy so that we can see the situation from the other’s perspective, praying, reflecting on instances of when you offended another person and they forgave you, and be aware that forgiveness does not happen all at once but is a process.

Read the article by visiting: https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/adult-health/in-depth/forgiveness/art-20047692

15.1.7. Social Influence – Conformity

Have you ever changed your behavior to match the behavior of a group? Maybe you wanted to behave the same as others, so you did not stand out. This is called conformity and can be a useful behavior to engage in, especially if you are motivated to be accepted by the group, called normative social influence, or are not sure how to act and the actions of other group members provide you with a cue called informative social influence. In the case of the former, a new student at a university may conform to the standards of a fraternity or sorority to be accepted by the chapter. This makes sense if you consider that human beings have a need to affiliate. In the case of the latter, many new students are excited to go to their first home football game. The environment is exciting, and they really want to be part of the larger community of students and fans of the team from within the area. If you have ever been to a sports event, you know there are certain types of rituals that are practiced by all such as what to do after a touchdown by the home team, after your team earns a first down, when the mascot tries to motivate the crowd, or at the end when the school fight song is sung. Veteran students act almost on autopilot, but like the new student at his or her first game (or the same for a fan at a game for the first time), they had to learn and took cues by observing the actions of others.

Solomon Asch (1951, 1956) demonstrated conformity in the lab through a simple experiment. He asked a group of six to eight participants to sit at a table and compare lines. They were shown a sample line and then asked which of three comparison lines matched the sample. The correct answer was fairly certain because the incorrect answers were obviously not even close to looking like the sample. Asch went around the table and asked each participant which comparison line matched the sample. Here’s the thing. All participants, but one, were part of the study unbeknownst to the actual participant. These confederates were asked for their answer first, and on 6 of 18 trials gave the correct answer. That means on 12 of 18 they gave an intentionally wrong answer. So, what did the participant do? The results showed that participants conformed to the actions of the group 35% of the time. To make sure something else did not better explain the results than conformity, such as the participants truly being confused by the task, a control group was used in which participants responded to the trials alone. In this case, mistakes were made only 5% of the time indicating that the participants in the experimental group were conforming as hypothesized. What did Asch conclude? Well, that under some circumstances people conform even in the face of clear physical evidence to the contrary. Why is that?

As with helping behavior, situational and dispositional factors are at work. In the case of dispositional, if we are attracted to the group, expect future interactions with the group, are low status compared to other group members (such as being in a training class with supervisors and you are just a normal worker bee), and you want to be accepted to by the group, we are more likely to conform. In the case of situational factors, conformity increases up to about 4 people. In other words, it does not keep rising as the group size increases but levels off. What if the unanimity of the group is broken, meaning we have at least one ally? Conformity falls from 35% to 25%. And finally, what if the task is difficult or complicated? Conformity will be higher, likely because we believe we are not understanding what we should be doing and will follow the lead of other group members who seem to comprehend.

15.1.8. Social Influence – Compliance

Efforts to get you to say yes to some request fall under the type of social influence called compliance. In his book, Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion, Robert B. Cialdini (1984) describes specific weapons of influence compliance professionals, or people whose job it is to get you to say yes such as car salesmen, telemarketers, politicians, and fundraisers, will use. These include tactics centered on reciprocation, commitment and consistency, social proof, liking, authority, and scarcity.

First, reciprocation says that we are more willing to comply with a request from another person if they did us a favor or gave a concession previously. We feel compelled to pay them back. Two techniques can be used. The Home Shopping Network often will show a deal and then right when you think they are finished describing it, will add on an additional item for free, and another after that, and finally will give free shipping if we make the purchase now. This is appropriately named “that’s-not-all.” Another technique has a seller, motivated to get rid of a product, ask a higher price than he/she really wants. When rejected, the price is lowered. The buyer now feels compelled to agree to the more favorable terms since a concession was made. This is called the door-in-the-face technique. Occasionally, we might find a naïve person who accepts our initial offer but if we must reduce our price, this was expected all along.

Second, commitment and consistency states that once we have committed to a position, we are more likely to display behavior consistent with our initial action when asked to comply with new requests. In the lowball procedure, we agree to a deal but soon after, the terms are changed. We accept the new terms even though they are less favorable. In the foot-in-the-door technique, a small request is asked for and agreed to, such as donating $5 to a charity. The person asking for the money then makes a larger request, say to donate $20 to the cause. Since we already agreed to donate money, we accepted the larger amount in lieu of the smaller one.

Third, social proof states that we are more willing to comply with a request if we believe other people like us are acting in the same way. This is why commercials are tailored to who is watching at any given time during the day. Early morning and maybe late afternoon when kids are watching, advertisers will show kids enjoying a new toy. Middle of the day when housewives are watching, the people in commercials are of the same demographic. If you are watching specific channels such as Univision or BET, commercials will have Hispanic or African Americans, respectively. Again, its all about motivating our behavior by making us think that others like us are doing the same thing.

Fourth, have you ever tried to get someone to do something by making yourself seem extra likeable to them? If so, you are using techniques falling under friendship/liking. I mean let’s face it. Are you more likely to comply with a request from your best friend or worst enemy? If we are specifically trying to present ourselves as more attractive or likeable to a person so that they comply with our request to purchase a new bedroom set, we are using the technique of ingratiation. If we use compliments about something someone said, how they look, or what they do, we are using flattery and for it to work, it must appear sincere and genuine.

Fifth, we are more likely to comply with a request if it comes from someone who knows what they are talking about. They are an authority on the subject, and we should listen to them. Lebron James should know what he is talking about when it comes to what tennis shoes to wear when playing basketball, right? Drug commercials will often have doctors discussing the benefits of the latest drug for restless leg syndrome or diabetes. I guess I should have written doctors in quotes such as “doctors” because the person we think is a doctor is really an actor, but still, the deception has the intended effect. We believe what this professional says because they have legitimate power and knowledge that we do not, conveyed by their position.

Finally, we are more likely to comply with a request if we believe a product is running out or becoming scarce. Act now. While supplies last. Final days of the sale, are all examples of the deadline technique. Sale ads typically employ this strategy as do coupons that restaurants and stores use. If you want a really great example of this strategy, just check out the Hooked app on your phone or on the web at – http://hookedapp.com/. Outside of using time to indicate a deal is scarce, some marketers will indicate only a certain number of a product exist and so if you want one, you need to do something about it as quick as you can – i.e., go buy it. Can you say Black Friday (which now starts on Thanksgiving night…or a week in advance…and runs for days after Friday… so much for the excitement of shopping the day after Thanksgiving)?

15.2. Motivation, for Worse

Section Learning Objectives

- Explain why smoking is a type of motivated behavior for the worst.

- Propose a way to understand what abnormal behavior is using features stated in the DSM-5.

- Explain why jealousy is a type of motivated behavior for the worst.

- Explain why social loafing is a type of motivated behavior for the worst.

- Explain how prejudice and discrimination can lead to motivated behavior for the worst.

- Explain why stigmatization of mental disorders is a type of motivated behavior for the worst.

- Explain why mob behavior is a type of motivated behavior for the worst.

- Explain why obedience is a type of motivated behavior for the worst.

15.2.1. Health Defeating Behaviors – Smoking

According to the CDC, smoking is “the single largest preventable cause of death and disease in the United States” About 480,000 Americans die each year from cigarette smoking and 41,000 of these deaths are due to secondhand smoke. Smoking rates are highest among American Indian/Alaska Natives, men, people aged 45-64 years, those with a GED, military personnel compared to civilians, homosexuals compared to heterosexuals, and people below the poverty line.

Source – https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/campaign/tips/resources/data/cigarette-smoking-in-united-states.html

So why might someone start to smoke, even though we know the risks today? Social pressure, especially during adolescence, is one major cause. Teens want to be cool or to try something new; a 2014 Surgeon General’s Report showed that about 90% of adult smokers started before age 18 and nearly 100% started by age 26. The tobacco industry also spends billions of dollars each year creating and marketing ads which make smoking seem glamorous and safe, and it does not help that it is shown in some popular media and in video games.

People continue to smoke due to being addicted to nicotine. The CDC says, “Nicotine affects a smoker’s behavior, mood, and emotions. If a smoker uses tobacco to help manage unpleasant feelings and emotions, it can become a problem for some when they try to quit. The smoker may link smoking with social activities and many other activities, too. All of these factors make smoking a hard habit to break.” Positive reinforcement from smoking, to include feeling relaxed and the smell of tobacco, and negative reinforcement, to include getting rid of the unpleasant feelings the CDC talked about, all contribute to continuing the behavior. Avoidance of withdrawal symptoms, to include irritability, dizziness, depression, weight gain, feeling tired, constipation and gas, headaches, feeling restless, and having trouble sleeping occur and in keeping with negative reinforcement.

Source – https://www.cancer.org/cancer/cancer-causes/tobacco-and-cancer/why-people-start-using-tobacco.html

Of course, the consequences of not quitting are severe, with death a definite possibility. Smoking is linked to lung diseases such as COPD and asthma; cancers such as lung, larynx, blood, bladder, stomach, and kidney (really smoking can cause cancer anywhere in the body); cataracts; type 2 diabetes mellitus; stroke; cardiovascular disease; and preterm delivery in pregnant women. Smoking also causes bad breath, longer healing times for wounds, a higher risk of peptic ulcers, decreased sense of smell and taste which can affect your quality of life, and increased risk of gum disease and tooth loss.

So why should you be motivated to quit if you are a smoker? Obviously, you can live longer. According to the CDC, 1 year after quitting, the risk of a heart attack drops sharply; 2-5 years later the risk for a stroke falls to about that of a nonsmoker; 5 years later the risks for cancers such as mouth, throat, and esophagus drop by half; and 10 years later, the risk for lung cancer drops by half. Quitting saves a considerable amount of money, considering packs of cigarettes can cost between $5 and $10 and smoking just one pack a day at the lower end of the range could save you over $1,800.00 a year. Smoking is becoming a hassle as more cities and states pass clean indoor air laws in public places. And finally, cigarette smoke can harm or kill your loved ones – people who may never have picked up a cigarette in their life. The American Lung Association says, “Children who live with smokers get more chest colds and ear infections, while babies born to mothers who smoke have an increased risk of premature delivery, low birth weight and sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS).”

Source – https://www.lung.org/stop-smoking/i-want-to-quit/reasons-to-quit-smoking.html

Note: Other health defeating behaviors such as alcohol, drug use, and comfort eating could be added to this section but in the interest of space, will not be.

15.2.2. Features and Costs of Abnormal Behavior

In Section 15.1.2, I showed that what we might consider normal behavior is difficult to define. Equally difficult is understanding what abnormal behavior is, which may be surprising to you. The American Psychiatric Association, in its publication, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5 for short), states that though “no definition can capture all aspects of all disorders in the range contained in the DSM-5” certain aspects are required. These include:

- Dysfunction – includes “clinically significant disturbance in an individual’s cognition, emotion regulation, or behavior that reflects a dysfunction in the psychological, biological, or developmental processes underlying mental functioning” (pg. 20). Abnormal behavior, therefore, has the capacity to make our well-being difficult to obtain and can be assessed by looking at an individual’s current performance and comparing it to what is expected in general or how the person has performed in the past. As such, a good employee who suddenly demonstrates poor performance may be experiencing an environmental demand leading to stress and ineffective coping mechanisms. Once the demand resolves itself the person’s performance should return to normal according to this principle.

- Distress – When the person experiences a disabling condition “in social, occupational, or other important activities” (pg. 20). Distress can take the form of psychological or physical pain, or both concurrently. Alone though, distress is not sufficient to describe behavior as abnormal. Why is that? The loss of a loved one would cause even the most “normally” functioning individual pain. An athlete who experiences a career ending injury would display distress as well. Suffering is part of life and cannot be avoided. And some people who display abnormal behavior are generally positive while doing so.

- Deviance – Closer examination of the word abnormal shows that it indicates a move away from what is normal, or the mean (i.e., what would be considered average and in this case in relation to behavior), and so is behavior that occurs infrequently (sort of an outlier in our data). Our culture, or the totality of socially transmitted behaviors, customs, values, technology, attitudes, beliefs, art, and other products that are particular to a group, determines what is normal and so a person is said to be deviant when he or she fails to follow the stated and unstated rules of society, called social norms. What is considered “normal” by society can change over time due to shifts in accepted values and expectations. For instance, homosexuality was considered taboo in the U.S. just a few decades ago but today, it is generally accepted. Likewise, PDAs, or public displays of affection, do not cause a second look by most people, unlike the past when these outward expressions of love were restricted to the privacy of one’s own house or bedroom. In the U.S., crying is generally seen as a weakness for males but if the behavior occurs in the context of a tragedy such as the Vegas mass shooting on October 1, 2017 in which 58 people were killed and about 500 were wounded while attending the Route 91 Harvest Festival, then it is appropriate and understandable. Finally, consider that statistically deviant behavior is not necessarily negative. Genius is an example of behavior that is not the norm.

Though not part of the DSM conceptualization of what abnormal behavior is, many clinicians add dangerousness to this list, or when behavior represents a threat to the safety of the person or others. It is important to note that having a mental disorder does not mean you are also automatically dangerous. The depressed or anxious individual is often no more a threat than someone who is not depressed and as Hiday and Burns (2010) showed, dangerousness is more the exception than the rule. Still, mental health professionals have a duty to report to law enforcement when a mentally disordered individual expresses intent to harm another person or themselves. It is important to point out that people seen as dangerous are also not automatically mentally ill.

This leads us to wonder what the cost of mental illness is to society. The National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) indicates that depression is the number one cause of disability across the world “and is a major contributor to the global burden of disease.” Serious mental illness costs the United States an estimated $193 billion in lost earning each year. They also point out that suicide is the 10th leading cause of death in the U.S. and 90% of those who die due to suicide have an underlying mental illness. In relation to children and teens, 37% of students with a mental disorder age 14 and older drop out of school which is the highest dropout rate of any disability group, and 70% of youth in state and local juvenile justice systems have at least one mental disorder. (Source: https://www.nami.org/Learn-More/Mental-Health-By-the-Numbers). In terms of worldwide impact, the World Economic Forum used 2010 data to estimate $2.5 trillion in global costs in 2010 and projected costs of $6 trillion by 2030. The costs for mental illness are greater than the combined costs of cancer, diabetes, and respiratory disorders (Whiteford et al., 2013). So, as you can see the cost of mental illness is quite staggering for both the United States and other countries.

In conclusion, though there is no one behavior that we can use to classify people as abnormal, most clinical practitioners agree that any behavior that strays from what is considered the norm or is unexpected and has the potential to harm others or the individual, is abnormal behavior.

15.2.3. Jealousy

In Section 15.1 we discussed love and types of it. The dark side of love is what is called jealousy, or a negative emotional state arising due to a perceived threat to one’s relationship. Take note of the word perceived here. The threat does not have to be real for jealousy to rear its ugly head and what causes men and women to feel jealous varies. For women, a man’s emotional infidelity leads her to fear him leaving and withdrawing his financial support for her offspring while sexual infidelity is of greater concern to men as he may worry that the children he is supporting are not his own. Jealousy can also arise among siblings who are competing for their parent’s attention, among competitive coworkers especially if a highly desired position is needing to be filled, and among friends. From an evolutionary perspective, jealousy is essential as it helps to preserve social bonds and motivates action to keep important relationships stable and safe. But it can also lead to aggression (Dittman, 2005) and mental health issues.

15.2.4. Social Loafing

In Section 15.1.4 we discussed how the presence of others can improve performance for easy tasks but make it worse for hard tasks, called social facilitation. If, in general, others can help us, their presence can also hurt us, called social loafing (Latane et al., 1979). Group work is a great example of this. If a group is relatively large, we may feel that others can pick up the slack if we do not complete our deliverables. Think about large lecture halls too. If the professor asks a question, you are one of maybe 100 students who could answer it. If you think about it in terms of percentages and in terms of responsibility, you are only 1% responsible for answering the question. What if your class has 250 students, as some of my Introduction to Psychology sections have had in the past? Now your responsibility is a whopping 0.4%. What if your class is much smaller and has 30 students? Your responsibility is 3.33% for answering the question.

Did you know that employers have recognized that social loafing in the workplace is serious enough of an issue that they now closely monitor what their employees are doing, in relation to surfing the web, online shopping, playing online games, managing finances, searching for another job, checking Facebook, sending a text, or watching YouTube videos? They are, and the phenomenon is called cyberloafing. Employees are estimated to spend from three hours a week up to 2.5 hours a day cyberloafing. So, what can employers do about it? Kim, Triana, Chung, and Oh (2015) reported that employees high in the personality trait of Conscientiousness (see Module 7 for a discussion) are less likely to cyberloaf when they perceive greater levels of organizational justice. So they recommend employers to screen candidates during the interview process for conscientiousness and emotional stability, develop clear policies about when personal devices can be used, and “create appropriate human resource practices and effectively communicate with employees so they feel people are treated fairly” (Source: https://news.wisc.edu/driven-to-distraction-what-causes-cyberloafing-at-work/). Cyberloafing should be distinguished from leisure surfing which Matthew McCarter of The University of Texas at San Antonio says can relieve stress and help employees recoup their thoughts (Source: https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/01/160120111527.htm).

How can we reduce social loafing? If an individual’s contribution to the group project can be identified and evaluated by others, if the group is small, if it is cohesive meaning the person values group membership, the task is seen as important, and if there is punishment for poor performance, social loafing will be less of an issue (Karau & Kipling, 1993). Back to the example of the professor asking a question in class. One strategy I use is to not ask the whole class, per se, but a much smaller area. I tend to bracket or identify a specific row or group of students to answer a question. If this is just 10 students of the class of 250, an individual student’s responsibility for answer has just risen from 0.4% to 10% or a 25-fold increase.

15.2.5. Prejudice and Discrimination

I am sure you have heard the terms prejudice and discrimination in the past and may think they are synonyms. Actually, they are not. Prejudice occurs when someone holds a negative belief about a group of people. In contrast, discrimination is when a person acts in a way that is negative against a group of people. So, prejudice is an attitude while discrimination is a behavior.

Interestingly, a person could be prejudicial but not discriminatory. Most people do not act on their attitudes about others due to social norms against such actions. A person could also be discriminatory without being prejudicial. Say an employer needs someone who can lift up to 75lbs on a regular basis. If you cannot do that and are not hired, you were discriminated against but that does not mean that the employer has prejudicial beliefs about you. The same would be said if a Ph.D. was required for a position and you were refused the job since you only have a bachelor’s degree.

How might we be motivated in a negative way in relation to prejudice? Well, we tend to see members of an outgroup as being more similar than members of our ingroup, called out-group homogeneity. We also tend to display favoritism toward our group and hold a negative view of members outside this group, called the in-group/out-group bias. This might lead us to worry about being judged by a negative stereotype applied to all members of our group. Steele et al. (1997) called this the stereotype threat and has been shown to impair the academic performance of African Americans (Steele & Aronson, 1995), though helping these students see intelligence as malleable reduced their vulnerability to the phenomenon (Good, Aronson, & Inzlicht, 2003; Aronson, Fried, & Good, 2002).

It is possible that we are not even aware we hold such attitudes towards other people, called an implicit attitude. Most people when asked if they hold a racist attitude would vehemently deny such a truth but research, using the Implicit Association Test (IAT) show otherwise (Greenwald et al., 1998). The test occurs in four stages. First, the participant is asked to categorize faces as black or white by pressing the left- or right-hand key. Next, the participant categorizes words as positive or negative in the same way. Third, words and faces are paired, and a participant may be asked to press the left-hand key for a black face or positive word and the right-hand key for a white face or negative word. In the fourth and final stage, the task is the same as in Stage 3 but now black and negative are paired and white and good are paired. The test measures how fast people respond to the different pairs and in general the results show that people respond faster when liked faces are paired with positive words and similarly, when disliked faces are paired with negative words.

Check out the Project Implicit website at – https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/

15.2.6. Stigmatization of Mental Disorders

Excerpt from Module 1 of Abnormal Behavior, 1st edition, by Alexis Bridley and Lee Daffin – https://opentext.wsu.edu/abnormal-psych/chapter/module-1-what-is-abnormal-psychology/

Overlapping with prejudice and discrimination in terms of how people with mental disorders are treated is stigma, or when negative stereotyping, labeling, rejection, and loss of status occur. Stigma takes on three forms as described below:

- Public stigma – When members of a society endorse negative stereotypes of people with a mental disorder and discriminate against them. They might avoid them altogether, resulting in social isolation. An example is when an employer intentionally does not hire a person because their mental illness is discovered.

- Label avoidance – In order to avoid being labeled as “crazy” or “nuts” people needing care may avoid seeking it altogether or stop care once started. Due to these labels, funding for mental health services could be restricted and instead, physical health services funded.

- Self-stigma – When people with mental illnesses internalize the negative stereotypes and prejudice, and in turn, discriminate against themselves. They may experience shame, reduced self-esteem, hopelessness, low self-efficacy, and a reduction in coping mechanisms. An obvious consequence of these potential outcomes is the why try effect, or the person saying ‘Why should I try and get that job. I am not worthy of it’ (Corrigan, Larson, & Rusch, 2009; Corrigan, et al., 2016).

Another form of stigma that is worth noting is that of courtesy stigma or when stigma affects people associated with the person with a mental disorder. Karnieli-Miller et. al. (2013) found that families of the afflicted were often blamed, rejected, or devalued when others learned that a family member had a serious mental illness (SMI). Due to this, they felt hurt and betrayed and an important source of social support during the difficult time had disappeared, resulting in greater levels of stress. To cope, they had decided to conceal their relative’s illness and some parents struggled to decide whether it was their place to disclose versus the relative’s place. Others fought with the issue of confronting the stigma through attempts at education or to just ignore it due to not having enough energy or desiring to maintain personal boundaries. There was also a need to understand responses of others and to attribute it to a lack of knowledge, experience, and/or media coverage. In some cases, the reappraisal allowed family members to feel compassion for others rather than feeling put down or blamed. The authors concluded that each family “develops its own coping strategies which vary according to its personal experiences, values, and extent of other commitments” and that “coping strategies families employ change over-time.”

Other effects of stigma include experiencing work-related discrimination resulting in higher levels of self-stigma and stress (Rusch et al., 2014), higher rates of suicide especially when treatment is not available (Rusch, Zlati, Black, and Thornicroft, 2014; Rihmer & Kiss, 2002), and a decreased likelihood of future help-seeking intention in a university sample (Lally et al., 2013). The results of the latter study also showed that personal contact with someone with a history of mental illness led to a decreased likelihood of seeking help. This is important because 48% of the sample stated that they needed help for an emotional or mental health issue during the past year but did not seek help. Similar results have been reported in other studies (Eisenberg, Downs, Golberstein, & Zivin, 2009). It is important to also point out that social distance, a result of stigma, has also been shown to increase throughout the life span suggesting that anti-stigma campaigns should focus on older people primarily (Schomerus, et al., 2015).

One potentially disturbing trend is that mental health professionals have been shown to hold negative attitudes toward the people they are there to serve. Hansson et al. (2011) found that staff members at an outpatient clinic in the southern part of Sweden held the most negative attitudes about whether an employer would accept an applicant for work, willingness to date a person who had been hospitalized, and hiring a patient to care for children. Attitudes were stronger when staff treated patients with a psychosis or in inpatient settings. In a similar study,

Martensson, Jacobsson, and Engstrom (2014) found that staff had more positive attitudes towards persons with mental illness if their knowledge of such disorders is less stigmatized, their work places were in the county council as they were more likely to encounter patients who recover and return to normal life in society compared to municipalities where patients have long-term and recurrent mental illness, and they have or had one close friend with mental health issues.

To help deal with stigma in the mental health community, Papish et al. (2013) investigated the effect of a one-time contact-based educational intervention compared to a four-week mandatory psychiatry course on the stigma of mental illness among medical students at the University of Calgary. The course included two methods involving contact with people who had been diagnosed with a mental disorder – patient presentations or two, one-hour oral presentations in which patients shared their story of having a mental illness; and “clinical correlations” in which students are mentored by a psychiatrist while they directly interacted with patients with a mental illness in either inpatient or outpatient settings. Results showed that medical students did hold a stigma towards mental illness and that comprehensive medical education can reduce this stigma. As the authors stated, “These results suggest that it is possible to create an environment in which medical student attitudes towards mental illness can be shifted in a positive direction.” That said, the level of stigma was still higher for mental illness than it was for a stigmatized physical illness such as type 2 diabetes mellitus.

What might happen if mental illness is presented as a treatable condition? McGinty, Goldman, Pescosolido, and Barry (2015) found that portraying schizophrenia, depression, and heroin addiction as untreated and symptomatic increased negative public attitudes towards people with these conditions but when the same people were portrayed as successfully treated, the desire for social distance was reduced, there was less willingness to discriminate against them, and belief in treatment’s effectiveness increased in the public.

Self-stigma has also been shown to affect self-esteem, which then affects hope, which then affects quality of life among people with SMI. As such, hope should play a central role in recovery (Mashiach-Eizenberg et al., 2013). Narrative Enhancement and Cognitive Therapy (NECT) is an intervention designed to reduce internalized stigma and targets both hope and self-esteem (Yanos et al., 2011). The intervention replaces stigmatizing myths with facts about the illness and recovery which leads to hope in clients and greater levels of self-esteem. This may then reduce susceptibility to internalized stigma.

Stigma has been shown to lead to health inequities (Hatzenbuehler, Phelan, & Link, 2013) prompting calls for stigma change. Targeting stigma leads to two different agendas. The services agenda attempts to remove stigma so the person can seek mental health services while the rights agenda tries to replace discrimination that “robs people of rightful opportunities with affirming attitudes and behavior” (Corrigan, 2016). The former is successful when there is evidence that people with mental illness are seeking services more or becoming better engaged, while the latter is successful when there is an increase in the number of people with mental illnesses in the workforce and receiving reasonable accommodations. The federal government has tackled this issue with landmark legislation such as the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008, and the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 though protections are not uniform across all subgroups due to “1) explicit language about inclusion and exclusion criteria in the statute or implementation rule, 2) vague statutory language that yields variation in the interpretation about which groups qualify for protection, and 3) incentives created by the legislation that affect specific groups differently” (Cummings, Lucas, and Druss, 2013).

15.2.7. Mob Behavior

I am sure you have seen footage on television of looters breaking into stores and taking what they want. Why might such spontaneous behavior occur? One possible explanation is what is called deindividuation or when we feel a loss of personal responsibility when in a group. Another explanation is what is called the snowball effect or when one dominant personality convinces others to act and then these others convince more and so forth. Finally, mob behavior may occur because large groups provide protection in the form of anonymity, making it hard for the police to press charges.

15.2.8. Social Influence – Obedience

In Section 15.1.7 and 15.1.8 we discussed two types of social influence to include compliance and conformity. You might say that both can lead to behavior for good. There are times when we need to conform to a larger group, and we comply to the requests of advertisers all the time. Really, not much harm is done though there is a degree of manipulation in compliance. A third type of social influence might be described as compliance with a command, or when one person orders another to engage in some behavior. This is called obedience.

Milgram (1963) conducted the seminal research on obedience and found that 65% of participants would shock another human being to death, simply because they were told to. His design consisted of two individuals – a naïve participant and like with Asch’s study, a confederate. The experimenter asked the confederate to choose either heads or tails when a coin was flipped. The confederate always won and chose to be the learner, leaving the participant to be the teacher. The learner was taken to a small room where he was hooked up to wires and electrodes by the experimenter, all while the teacher watched. After this, the teacher was taken to an adjacent room and sat in front of a shock generator. His task was to read a list of word pairs to the learner and once through the list, state one of the words and wait for the learner to identify the other word in the pair. If the learner was correct the teacher would proceed to the next word in the list and wait for the learner to state its pair. If wrong, the teacher was to deliver a shock to the learner and with subsequent incorrect answers, continue to the next higher voltage. The shock generator started at 30 volts and moved up in increments of 15 volts, to a max of 450 volts which would kill the learner. As the experiment proceeded, the learner would occasionally scream, holler, beg to be let go, complain about a heart condition, or say nothing. When these behaviors occurred was scripted but the reaction of the teacher was not. Often, he would turn to the experimenter and suggest that maybe the experiment should be stopped. The experimenter would state one of a few different replies to include, “The experiment requires that you continue,” “You have no other choice. You must go on,” or “Please continue.” Again, results showed that 65% of participants, who were all male in the initial study, continued on to the point of shocking the learner to death.

So, what might increase or decrease obedience? In terms of reducing obedience, if the learner was in the same room and only a few feet away, obedience fell to 40%. If the teacher had to place the learner’s hand on the shock plate, obedience fell to 30%. If the experimenter was not physically present in the room but gave his commands from over the phone, obedience fell to 20.5%. If two authorities were present but one insisted the teacher go on while the other insisted that the teacher stop, obedience fell to 0%. Obedience increased to 92.5% if instead of the teacher administering the shock, he told a peer to do so (incidentally, also a confederate). What about women? Do you think they might do better or worse? Results showed that they did the same – 65% of women took the learner to maximum shock.

Of course, one explanation for the results was that they were conduced over 50 years ago and people today would never do such a thing. I suggest you examine the following if you believe this is true (Burger, 2009):

https://www.apa.org/pubs/journals/releases/amp-64-1-1.pdf

15.3. Explaining Behavior, For Better or Worse, Through Values

Section Learning Objectives

- Define and list types of values.

- Outline methods to measure values.

- Clarify how values demonstrate both universality and diversity in behavior.

- Outline sources of individual differences in basic values.

- Show how values relate to personality.

- Describe how values predict real-world outcomes.

So how might we explain the behaviors mentioned above, whether for better or worse? One possible way, and please be clear, this is not the only way, is to examine universal human values. We have addressed some possible reasons why the behaviors in question in this module and others occur, but values could be a unifying construct that explains them all on some level. Read Section 15.3 and then decide for yourself.

15.3.1. Defining Values

Values have six main components that define them (Schwartz, 1992, 2005a). First, they are beliefs with emotional aspects. If a person is independent and can achieve success, they are happy. If their independence is threatened, they become highly vigilant, and if it is taken from them, they become upset. Second, values are not linked to specific actions or situations but define behavior in all situations. This is unlike norms which are particular to certain actions or situations. Third, they are linked to specific goals. Fourth, they are ordered, meaning some values are promoted above others. Fifth, they are relative. In any given situation, more than one value is relevant. For instance, a religious person pursues conservation values at the expense of openness to change values such as Hedonism, Stimulation, and Self-Direction. Sixth, values are standards by which we can judge our behavior. If our behavior is consistent with our values, this process occurs subconsciously but if behavior is not, it raises our values to conscious awareness. So, when taken together, a value is a (1) belief (2) pertaining to desirable end states or modes of conduct, that (3) transcends specific situations; (4) guides selection or evaluation of behavior, people, and events; and (5) is ordered by importance relative to other values to form a system of value priorities (Schwartz, 1994).

There are ten main values arranged around two main axes. On the one axis, you have Openness to Change values versus Conservation values. Openness to Change includes Hedonism or the pursuit of pleasure, Stimulation or pursing novelty or excitement in life, and Self-direction or independent thought and action. Opposed to these are Conservation values which include Conformity or following social norms, Tradition or following the customs of your group, and Security or stability and safety. The other axis consists of Self-Enhancement values such as Power or social status and prestige or control over people and resources and Achievement or personal success through demonstrating competence as defined by society. Opposed to them are Self-transcendence values which include Benevolence or care and concern for those in your in-group and Universalism or care for all others.

There is also a shared motivational emphasis of adjacent value types such that:

- Power and achievement emphasize social superiority and esteem

- Achievement and hedonism focus on self-centered satisfaction

- Hedonism and stimulation involve a desire for affectively pleasant arousal

- Stimulation and self-direction involve intrinsic interest in novelty and mastery

- Self-direction and universalism call for reliance upon one’s own judgment and comfort with the diversity of existence

- Universalism and benevolence are concerned with enhancement of others and transcendence of selfish interests

- Benevolence and conformity involve a call for normative behavior that promotes close relationships

- Benevolence and tradition promote devotion to one’s in-group

- Conformity and tradition entail subordination of self in favor of socially imposed expectations

- Tradition and security stress preserving existing social arrangements that give certainty to life

- Conformity and security emphasize protection of order and harmony in relations

- Security and power stress avoiding or overcoming the threat of uncertainties by controlling relationships and resources.

The motivational differences between the various values are continuous, not discrete, with greater overlap in meaning near the boundaries of adjacent value types.

15.3.2. Measuring Values

15.3.2.1. The Schwartz Value Survey (SVS; Schwartz, 1992, 2005a). The first instrument developed to measure values based on this framework is the Schwartz Value Survey (SVS; Schwartz, 1992, 2005a). The SVS presents two lists of value items. The first contains 30 items that describe potentially desirable end-states in noun form; the second contains 26 or 27 items that describe potentially desirable ways of acting in adjective form. Each item expresses an aspect of the motivational goal of one value. An explanatory phrase in parentheses following the item further specifies its meaning. For example, ‘EQUALITY (equal opportunity for all)’ is a universalism item; ‘PLEASURE (gratification of desires)’ is a hedonism item.

Respondents rate the importance of each value item “as a guiding principle in MY life” on a 9-point scale labeled 7 (of supreme importance), 6 (very important), 5 (unlabeled), 4 (unlabeled), 3 (important), 2 (unlabeled), 1 (unlabeled), 0 (not important), -1 (opposed to my values). The nonsymmetrical nature of the scale is stretched at the upper end and condensed at the bottom so as to be able to map the way people think about values but also allows respondents to report opposition to values that they try to avoid expressing or promoting. This is especially important for cross-cultural studies as people in one culture may reject values held dear in other cultures. The SVS has been translated into 48 languages.

The score for the importance of each value is the average rating given to items designated a priori as markers of that value. The number of items assessing each value ranges from three for hedonism to eight for universalism. Only value items that have demonstrated near-equivalence of meaning across cultures are included in the indexes. Alpha reliabilities of the 10 values average .68, ranging from .61 for tradition to .75 for universalism (Schwartz, 2005b).

15.3.2.2. The Portrait Values Questionnaire. The Portrait Values Questionnaire (PVQ) is an alternative to the SVS developed to measure the ten basic values in samples of children from age 11, the elderly, and persons not educated in Western schools that emphasize abstract, context-free thinking. The SVS had not proven suitable to such samples.

The PVQ includes short verbal portraits of 40 different people, gender-matched with the respondent (Schwartz, 2005b; Schwartz, et al., 2001). Each portrait describes a person’s goals, aspirations, or wishes that point implicitly to the importance of a value. For example: “Thinking up new ideas and being creative is important to him. He likes to do things in his own original way” describes a person for whom self-direction values are important. “It is important to him to be rich. He wants to have a lot of money and expensive things” describes a person who cherishes power values.

For each portrait, respondents answer: “How much like you is this person? Potential responses include: very much like me, like me, somewhat like me, a little like me, not like me, and not like me at all. Participants’ own values are inferred from their self-reported similarity to people described implicitly in terms of particular values. Participants are asked to compare the portrait to themselves rather than themselves to the portrait. Comparing other to self directs attention only to aspects of the other that are portrayed.

The verbal portraits describe each individual in terms of what is important to him or her. Thus, they capture the person’s values without explicitly identifying values as the topic of investigation. The PVQ asks about similarity to someone with particular goals and aspirations (values) rather than similarity to someone with particular traits.

The number of portraits for each value ranges from three (stimulation, hedonism, and power) to six (universalism). The score for the importance of each value is the average rating given to these items. Alpha reliabilities of the ten values average .68, ranging from .47 for tradition to .80 for achievement (Schwartz, 2005b).

15.3.3. Cross-Cultural Variation in Values: Universality and Diversity

Schwartz and Sagiv (1995) found substantial support for the claim that ten motivationally distinct value types are recognized across cultures and used to express value priorities. In terms of common cross-cultural variations in the locations of single values, spiritual life emerged most commonly in benevolence, universalism, or tradition regions, implying a broad meaning of transcendence of the material interests of the self. What differs are the reasons for transcending self- interest implied by the locations. For instance, the welfare of close others is located in benevolence, the welfare of all others in universalism, and the demands of transcendent authority in tradition. The different locations may represent something about the nature of spirituality in different cultures.

In terms of ‘self-respect,’ it emerged with almost equal frequency in regions of achievement and self-direction values. In Communist countries, when emerging with achievement values, self-respect may be built primarily on social approval obtained when one succeeds according to social standards. Self-respect emerged in the achievement region in almost all Eastern European samples possibly reflecting a socializing impact of communism with its emphasis on grounding self-worth in evaluation of one’s group. In Capitalist countries, when emerging with self-direction values, self-respect may be linked more closely to living up to one’s independent, self- determined standards. Self-respect emerged in the self-direction region in most strongly capitalist countries (Schwartz and Sagiv, 1995).

Schwartz and Sagiv (1995) also report that ‘healthy’ emerged most frequently in the region of security values signifying a concern for physical and/or psychological safety (i.e., maintaining health and avoiding illness). It emerged less frequently with hedonism values signifying a meaning of enjoying the pleasures of a healthy body rather than fearing ill-health. Not infrequently, it emerged in the region of achievement, which falls between security and hedonism.

For the Japanese, ‘true friendship’ was located in the security values region in the total sample and split half analyses. This may mean that for these students, friendship is valued more for the security it provides rather than for the care it expresses toward close others. For the Japanese, forgiving was located in the middle of the universalism rather than the benevolence value region in all analyses. This implies that forgiving is motivated more by an appreciation of life’s complexities (universalism) than by a desire to be kind to others (benevolence) (Schwartz and Sagiv, 1995).

Three sets of data measuring values differently (the SVS, PVQ, and World Value Survey; sample sizes of 41,968 across 67 countries, 42,359 across 19 European countries, and 84,887 from 62 countries, respectively) addressed the question of how much do values vary across countries and to what extent do citizens within a country share values (Fischer and Schwartz, 2010). Results show that there was greater consensus than disagreement on value priorities across countries with autonomy, relatedness, and competence showing a universal pattern of high importance. Only conformity values seem to measure culture as shared meaning systems.

15.3.4. Sources of Individual Differences in Basic Values

15.3.4.1. Processes linking background variables to value priorities. People’s life circumstances provide opportunities to pursue or express some values more easily than others. For example, wealthy persons can pursue power values more easily, and people who work in the free professions can express self-direction values more easily. Life circumstances also impose constraints against pursuing or expressing values. Having dependent children constrains parents to limit their pursuit of stimulation values. People with strongly ethnocentric peers find it hard to express universalism values. In other words, life circumstances make the pursuit or expression of different values more or less rewarding or costly.

Typically, people adapt their values to their life circumstances. They upgrade the importance they attribute to values they can readily attain and downgrade the importance of values whose pursuit is blocked (Schwartz & Bardi, 1997). Thus, people in jobs that afford freedom of choice increase the importance of self-direction values at the expense of conformity values (Kohn & Schooler, 1983). Upgrading attainable values and downgrading thwarted values applies to most, but not to all values. The reverse occurs with values that concern material well-being and security. When such values are blocked, their importance increases; when they are attained easily, their importance drops. Thus, people who suffer economic hardship and social upheaval attribute more importance to power and security values than those who live in relative comfort and safety (Inglehart, 1997).

15.3.4.2. Age and life course. As people grow older, they tend to become more embedded in social networks, more committed to habitual patterns, and less exposed to arousing and exciting changes and challenges (Glen, 1974). This implies that conservation values (tradition, conformity, security) should increase with age and openness to change values (self-direction, stimulation, hedonism) decrease. Once people enter families of procreation and attain stable positions in the occupational world, they tend to become less preoccupied with their own strivings and more concerned with the welfare of others (Veroff, Reuman, & Feld, 1984). This implies that self-transcendence values (benevolence, universalism) increase with age and self-enhancement values (power, achievement) decrease over time.

15.3.4.3. Gender. Various theories of gender differences have led researchers to postulate that men emphasize agentic-instrumental values such as power and achievement, while females emphasize expressive-communal values such as benevolence and universalism (Schwartz & Rubel, 2005). Most theorists expect gender differences to be small. Analyses with the SVS and PVQ instruments across 68 countries yield similar results. Gender differences for eight values are consistent, statistically significant, and small; differences for conformity and tradition values are inconsistent. It is important to point out that women gave higher priority than men to tradition values in all 20 European Social Survey (ESS) countries but conformity values in only 13 countries.

So, sex differences were highly consistent for power (men higher in 96% of the samples) and benevolence (women higher in 90% of the samples). Differences were quite consistent for stimulation (men higher), universalism (women higher), hedonism (men higher), and achievement (men higher) and differences were a bit less consistent for self-direction values (men higher in 79%). Men attribute more importance to self-enhancement values (power, achievement) whereas women attribute more importance to self-transcendence values (universalism, benevolence).

In a follow-up study, Schwartz and Rubel-Lifschitz (2009) reexamined sex differences in value priorities across countries specifically to explore a potential relationship of values with gender equality. Previous research has shown that gender equality is correlated highly with such societal characteristics as country wealth, cultural autonomy, and democracy. This pattern led the researchers to assume positive associations of value priorities with benevolence, universalism, self-direction, stimulation, and hedonism, while correlating negatively with security, tradition, conformity, power, and achievement. Though the correlations are in the same direction for both males and females, they may be stronger for one gender over the other, and due to this, changing societal conditions may increase the value’s importance more sharply for that gender. Consider that universalism values have been shown to be more important to women (Schwartz & Rubel, 2005) and so if society increases its expectations of citizens to take part in civil rights movements, both genders will see a rise in the importance of the value, but the increase would be greater for women. Likewise, power values are greater for men (Schwartz & Rubel, 2005) and if society imposes sanctions against pursuing self-interest at the expense of others, both sexes will see a decrease in the importance of the value, but the decrease will be smaller for men. It should be stated that some values may not hold greater importance to one gender.

To test the dynamics of this relationship, the authors used a strict probability sample representing citizens aged 15 and older in each of 25 countries (Study 1) or a sample of college students from 68 countries (Study 2) and administered either the Portrait Value Questionnaire (PVQ; Study 1) or the Schwartz Value Survey (SVS; Study 2). Results showed that the inherently greater importance of benevolence and universalism values for women and stimulation for men, increases positive effects of gender equality on these values for that gender compared to the other gender. For men, the greater importance placed on power and achievement values reduces the negative effects of gender equality on these values. No inherent link was hypothesized or found for either gender in regard to hedonism, security, conformity, or self-direction.

In the student sample only, self-direction values showed smaller sex differences in high gender equality countries while in low gender equality countries, men emphasized these values more than women. As self-direction values correlate with education and the ratio of women to men is greater in high as compared to low gender equality countries (119/100 and 49/100, respectively), it may be that greater equal expectations for independent thought in the universities of high gender equality countries explain this interesting finding.

15.3.5. Do Values Relate to Personality?