Module 3: Goal Motivation

Module Overview

Most likely the term goal is not new to you. You likely have been taught from day one to set goals for yourself and then give it your all to achieve them. But how exactly do we do that? What is this ‘all’ that we need to give? Module 3 will tackle the issue of goal motivation by defining goals; sharing some features of goals; and discussing characteristics of goals such as how specific and difficult they are, what their level is in a hierarchy of goals, and what we need to do to stay the course. We then turn our attention to the effect of achieving the goal. Unfortunately, success will not always be the case, so what do we do if we fail or just cannot finish the goal?

Module Outline

Module Learning Outcomes

- Explain the importance of goals through their features, sources, and possible uses.

- Outline four characteristics of goals and how they interact with one another.

- Describe strategies to bring about goal achievement.

- Outline strategies to deal with goal failure.

3.1. Defining Goals

Section Learning Objectives

- Define goal.

- Define value and contrast its meaning with goal.

- Clarify how goals are overprescribed.

- Outline features of goals.

- List and describe sources of goals.

3.1.1. What is a Goal?

The term goal is likely not new to you, and I bet you have heard it numerous times already today. A friend, spouse, significant other, parent, etc. might have asked what your plans are for the day or what do you hope to accomplish. Outside of others attempting to motivate your behavior, you might have done this as well using to-do lists made on post-it notes or your planner. Going back further, growing up, our family, teachers, and friends ask us what we want to be when we get older. All of this represents what are called goals, or goal-directed behavior. But what is a goal?

A goal is an objective or result we desire that outlines how we will spend our time and exert energy. To be successful, we must be dedicated to it, which means choosing a course of action and sticking to it. Goals and values are not the same thing. A value reflects what we care about most in life and may guide us through decisions we have to make. Sample values include peace, meaning, connection, belongingness, success, power, etc. You might even value being healthy and well, but just because you value it does not mean you will do anything about it. Goals can help keep our values and behavior in line with one another by saying we will lose 50 pounds by the end of the year and work out 5 times a week. Our actions mirror what we care about most, or our values and goals are working to the same end.

What if you value knowledge or education? You might set a goal to obtain your bachelor’s degree. You spend your time and energy studying, going to classes, writing papers, asking questions, etc. After four years, you will be happy to take your diploma which is the incentive (pull) motivating you. You might even be driven to obtain the highest grades you can earn so that you are competitive when you hit the job market or apply to graduate school. This achievement motivation is the push of motivation (more on this in Module 8). So, the goal of obtaining your degree is affected by both push and pull.

Through our goals we can achieve more, which leads to higher levels of self-confidence and pride in our work and accomplishments. Depending on what our goal is, our performance may even improve. Let’s say our goal is to learn how to use Microsoft Publisher. The result of the goal is that we can now produce nice-looking monthly newsletters, which increases the value of what we contribute to the company we work for. But to be clear and fair, goals can be overprescribed or used too much such that we fail to realize the importance of nongoal tasks, develop an inhibition in learning, engage in increased unethical behavior focused on achieving our goal, and at times, experience a reduction in intrinsic motivation (Welsh & Ordonez, 2014; Ordonez et al., 2009).

Goals are rather interesting to consider. Not all goals are created equal. Some are large. Some are small. Getting a Bachelor of Art in Psychology involves a lot of time, responses, lost opportunities, and energy costs. Running a full marathon requires months of dedication, training, and eating well to be ready for the big day. How might this compare to sitting down to write a paper for this class? The paper is a smaller, or maybe simpler, goal, than earning a degree. The word simpler is important here because it shows that goals can be complex too. They may include both positive and negative features. If you are truly dedicated to getting the highest grade possible, this will come at the expense of time spent having fun, but the rewards in the future have the potential to be greater for having done so. The lost time from other tasks so you can write the paper is called an opportunity cost in Module 5 but what you learn and earning an A on the assignment is positive. Another way to think about the positive and negative features is to consider what skills you need to have to achieve your goal (see Module 1). Most psychology programs require majors to take statistics. This is of course a daunting task for many students. If this is you, then recognizing your difficulties with math early on can help you to obtain the necessary help to be successful in the class. I guess you could view the extra work as a negative but if in the end you understand the material and complete the task, then it was a positive feature overall.

So how do you get to this success? Planning and more planning is key. To prepare for a marathon, you need to slowly build up the miles. A plan is needed. Let’s say you start by running a total of 14 miles in the first week, done over four alternating days. In Week 2 you follow the same schedule but run 15 miles. By Week 7 you are running 20 miles and 32 miles by Week 15. Add to that you went from running about 3 days a week to 5 days a week. You also add in weight training and stretching to your plan and work on losing weight. Wow. That is a lot of work…and dedication. You need something to help you keep going. That is where incentives come in, especially with something like earning a B.A. or Ph.D. Maybe your parents offer to get you a car if you keep your grades up through the first two years. You can reward your own hard work and success with some time off or buying something fun. In terms of the marathon preparation, give yourself an extra day off as you achieve goals.

In Module 4 we will discuss stress and coping. As you will see, the cause of our stress is not often from one source but multiple sources. So, multiple demands are present at the same time to tax our resources. So too, it goes with goals. Oftentimes, we have multiple goals we are trying to balance… and achieve. As a student you want to earn your bachelor’s degree by successfully completing your classes. But you might also want to play on the baseball team, work for the school newspaper, or gain research experience. These are additional goals that compete for our time and resources. And our goals often lead to stress so the discussion of goals, stress and coping, and the economics of motivated behavior (Modules 3-5 in this book) go hand-in-hand and overlap in many ways as you will see.

3.1.2. Where Do Our Goals Come From?

We have established that all human beings have goals, and often more than one at a time. But where do these goals come from? In this section we will briefly explore potential sources of goals to include both internal and external sources.

First, goals arise from our own desires or efforts to improve ourselves. In Module 6 you will get a taste of this and a preview of the area of psychology called behavior modification. When we engage in purposeful change in our own behavior through a specific plan, we call this self-modification. We might want to exercise more often, drink less soda, drink more water (or both goals at the same time), practice better time management skills, quit smoking, overcome a fear, cease negative cognitions about our ability to achieve success, etc. Once we realize we need to make change, we develop a plan, execute it, and then measure to see if it was successful. This process will be described in general in Section 3.3 and represents goal-directed or motivated behavior.

Second, our goals might arise from a desire to satisfy our psychological needs as we will see in Module 8. Some people are driven by power and so, will engage in tasks that allow them to be the leader and exert their will on others. Others wish to be part of a group and spend time with people like them. Some, like myself, want to achieve success in all endeavors that are undertaken. Whatever form your psychological needs take, you will be motivated to create goals that help you satisfy them. At times, our needs are physiological in nature, and in Module 14 we will explore goal-directed behavior meant to satisfy hunger or thirst, regulate our body temperature, or obtain rest.

Third, as human beings, we try to gain a sense of whether we have the skills necessary to achieve the goal, called self-efficacy. Past successes and failures affect our self-efficacy, which can then affect how motivated we are to engage in a specific goal-directed behavior. As you will see in Module 10, human beings are also motivated to evaluate their performance on a task by comparing their performance against the performance of others, called a social comparison. For instance, a high school baseball player will compare his stats against those of his teammates to see how good he is in relation to his peers. Self-efficacy affects goal motivation in terms of procrastinating getting the task done. Results of one study showed that students with a low perceived self-efficacy were more likely to procrastinate and had low goal achievement than those with high self-efficacy (Waschle et al., 2014).

Finally, our goals sometimes arise from outside of us. A supervisor may motivate his employees to sell more product by offering a gift card to a local restaurant to the top seller for the day. Think of this as dangling a carrot in front of a horse. In Module 12 we will discuss motivated behavior in terms of compliance behavior. Advertisers try to activate the goal-directed behavior of customers driving to their store to obtain some prized possession because a special price is being offered only for a short time, called the deadline technique. Does it work? Think about your own behavior and apps such as Hooked. If you have never used it, try it out. The app is named appropriately.

3.1.3. For What Do We Use Goal Setting?

So, for what are goals used? Everything. Goal setting is helpful in rehabilitation (Wade, 2009), for organizations (Latham, 2004), for students earning a bachelor’s degree (Dobronyi, Oreopoulos, & Petronijevic, 2017), for those with intellectual disabilities (Garrels, 2016); for increasing physical activity in kids at summer camp (Wilson, Sibthorp, & Brusseau, 2017), for those suffering from chronic low back pain (Gardner et al., 2015), for helping children engage in weight-related behavior change (Fisher et al., 2018), for better managing diabetes (Miller & Bauman, 2014), etc. Really, the sky is the limit here and setting goals can be used to direct our behavior to positive ends.

3.2. Characteristics of Goals

Section Learning Objectives

- Define and exemplify goal difficulty.

- Define and exemplify goal level.

- Define and exemplify goal specificity.

- Define and exemplify goal commitment.

Several features of goals are important to mention. We will discuss goal difficulty, level, specificity, and commitment or striving.

3.2.1. Goal Difficulty

First, goal difficulty is an indication of how hard it will be to obtain the goal. So, which type of goal do you think would lead to a higher sense of pride in us – a simple or a difficult goal? More difficult goals have higher incentive value because they are harder to obtain. An example would be trying to earn your Ph.D. in Organic Chemistry. Of course, the likelihood that we may fail is greater, but if we are successful, we will feel a sense of achievement that is unmatched, than say, if we chose an easier major. The same goes for taking more challenging classes. We experience greater pride once we have successfully passed them (and our sense of relief is likely greater too!).

3.2.2. Goal Level

Our goals can be ranked in a hierarchy, with higher level goals having more value than lower-level ones. This is called goal level. Its sort of like making a list of all the things we need to get done in a day, then ordering them from least to most important. Of course, getting done our really important goals will leave us happier and more content than easier, less important ones. Think about what you accomplished yesterday. Did you have a higher-level goal that you achieved? How did you feel about finishing it? My goal on the day I wrote this module was to finish the module and as I near the end of writing and revising, I am feeling good about myself. The day before, cleaning was at the top of my list of goals to achieve, with finishing work for a leadership certification course I was in, being right below. It took me until later in the evening to finish it all, and once done, I rewarded myself with some time on the Xbox One (incentive).

3.2.3. Goal Specificity

To help us be more successful with achieving these higher-level goals, we will want to be as precise as possible with defining the goal. Called goal specificity, the more specific our goal, the better our planning can be. If we know that we want to lose 10 pounds by the end of the summer and it is early May now, then we can engage in specific behaviors to achieve this goal. Let’s take a step back. I have struggled with my weight all my life. I am the textbook example for rollercoaster weight – I lose, then gain, then lose, and gain, etc. Over the past few years, I have been on the gain side of the hill, and it seems to keep going up with no drop off. I knew I had to lose weight and that I would do so through exercise and eating better. This is specific, but not specific enough. Until I recently went to the doctor and had blood work done, I did not know that I was prediabetic and that the reason why I did not seem to be experiencing the benefits of the downward side of the hill was that my sugar levels were very out of whack. Basically, it did not matter how much exercise or how well I thought I was eating, I would not lose weight. Or if I did, I would likely not keep it off. I am still exercising but now have a specific plan to eat better thanks to my doctor – reducing sugar, managing overall carbs, eating a lot of protein, and watching, but not obsessing over, fat intake. The change is working, and I feel better too. I was so sluggish and tired all the time, but my energy levels have increased.

3.2.4. Goal Commitment

Goal commitment/striving, or sticking to the goal, is generally higher when the goal is more difficult. Why? We need to invest more time and energy into the goal’s completion and so maintain our focus/attention on the goal. To increase commitment, you could announce your goal publicly (Salancik, 1977). Every one of us makes New Year’s resolutions, but how many actually follow through with them? We might stick with going to the gym to get in shape and lose weight beyond January if we tell others about our goal. In fact, try and find someone who shares the same resolution/goal and go to the gym with them or engage in healthy eating together (Jirka & Holland, 2017).

Another interesting twist on staying committed to our goals relates to perfectionism. Eddington (2013) contrasted socially-prescribed (SPP; external) and self-oriented (SOP; internal) perfectionism and goal adjustment in a sample of 388 students and found that students who had a SPP orientation were more depressed, less optimistic about goal success, and used maladaptive coping strategies. In contrast, SOP oriented students were more optimistic, had stronger emotional responses to success and failure, and were more likely to re-engage with their goals as a form of adaptive coping, if failure did occur.

Khenfer, Roux, Tafani, and Laurin (2017) found that for religious people, belief in divine control increased goal commitment when the individual’s self-efficacy (i.e., belief in their ability to complete a task) was low. Nelissen (2017) found that giving participants negative feedback about their progress toward completing a goal resulted in lower levels of success and persistence, unless they experienced hope. As such, the author speculates that hope is an affective mechanism that helps the individual regulate energy expenditure when striving to complete a goal. Finally, internal or autonomous motivation predicted the actions of athletes to persist in the face of increased goal difficulty as well as to display positive affect, adaptive coping, and future interest in the task (Ntoumanis et al., 2013).

3.3. Goal Achievement and Failure

Section Learning Objectives

- Describe the process of developing a goal statement.

- Contrast distal and proximal goals and their use in completing complex goals.

- Clarify when we should implement our plan.

- Clarify how we assess our progress.

- Describe what failure looks like and why we fail.

- Suggest strategies to deal with failure.

3.3.1. Goal Achievement through Goal Setting

For your goal to be completed successfully and to avoid failure, you should ideally create a goal statement and then from this a plan. Next implement the plan and then check in to see how it is going. So how exactly do you do all of this?

3.3.1.1. Coming up with a goal statement. To be able to create a plan, you have to know exactly for what you are creating a plan. This is akin to developing a research design to test your hypothesis. The hypothesis is your specific, testable prediction (see Module 1) and concerns some aspect of behavior you wish to know more about. But what is that behavior? Well, we know what it is because we have operationally defined it or gave a specific description of what it is that we are studying. Goal setting is no different.

We start by creating a goal statement. What, specifically, do you want to achieve? Does the goal involve anyone but yourself? Do you need to be in a certain location to obtain it or at a certain time? If you want to work out more, you will need to attend a gym and could do so in the morning, as this is when you have the most time. Do you need certain items to work on your goal? In the gym example, this might be a journal to record your workouts or weight training gloves. The more specific you are, the more likely you will be successful.

Next, your goal should be realistic and attainable. Are you willing and able to obtain the goal? If your goal is high in terms of goal level, this does not mean it will not be attainable. In fact, you are more likely to achieve it since it is something you are passionate about. It would be a labor of love for you. Low level goals are not very motivational. When we select a goal, we are excited about, we adopt a can-do attitude, procure whatever resources might be necessary, and see ourselves as worthy of the goal.

The goal should be timely too. Be clear about how much time you are granting yourself to complete the goal. Some goals will take longer than others to achieve. For instance, a bachelor’s degree cannot be obtained in a few months. Part of being realistic is knowing how much time you will need. Allow yourself four years for your degree but finishing a good book should not take that long. If your goal is to finish reading a 500-page book, allow yourself a month for instance. This translates to about 17 pages of reading a day which is realistic and completes the reading of the book in a fair amount of time. Keep in mind that if you do not assign a time frame for the goal’s completion, you have no sense of urgency to get it done.

It’s also a good idea to make your goal tangible. If you can sense it, or see it with your eyes, smell it with your nose, taste it with your mouth, touch it with your hands, or hear it with your ears, it becomes even more real. So how might you make obtaining your degree tangible? Imagine yourself holding the diploma in your hands, hearing your family cheer for you, and seeing their happy and proud faces.

3.3.1.2. Goal planning. Finally, your goal should be measurable. As with the hypothesis being tested with a research design, you must know if your prediction was correct. To determine correctness, you need to measure the variable you operationally defined. In terms of your goals, if you wanted to work out five days a week, you can measure your success by looking at your journal or the app for your wearable device and count the number of days you worked out each week. If this adds up to five or more days, your goal was achieved. This is where your plan comes in. In your plan, you will specify the exact way you will record data, what the timeframe is to complete the goal, recognize if you are engaging in any behavior now to achieve the goal at least in part, determine where you go from there, and then figure out the steps to help you.

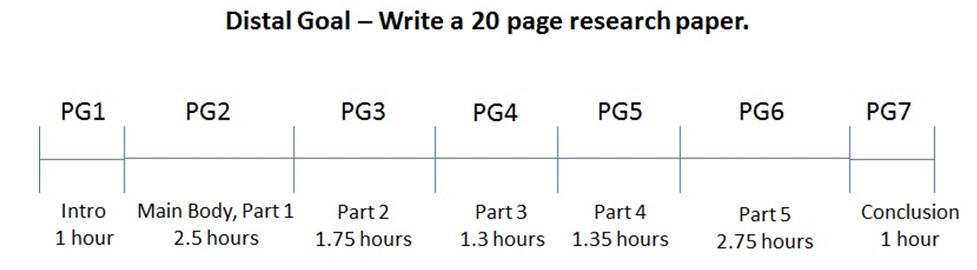

What do I mean by steps? Recall that goals can be simple or complex. A simple goal such as writing a 1-page reflection paper does not require steps to complete it, even if you are not very confident in your writing ability. Writing a 20-page research paper is a much more complex task and can be broken down into smaller steps to complete. The larger goal of writing the 20-page paper is a distal goal or one that is distant and far off in time. It will take us many days of working to finish the paper, so we likely cannot start it now and finish it in a few hours. If we decide to write the Introduction first, then part 1 of the main body, followed by part 2, and so forth, and then finish with the conclusion, we would have broken up the larger paper into maybe 7 smaller, manageable tasks. These are our subgoals, also called proximal goals. Notice the word proximity in proximal. Proximity means close and in terms of time, proximal goals are completed sooner or closer in time. It may only take an hour or so to write the Introduction. The parts of the main body may take a few hours each. The conclusion, like the Introduction, can likely be written in about an hour. All these subgoals work to the completion of the larger distal project or goal. Once achieved, the products of the subgoals can be combined to form the final product of a 20-page paper or distal goal. Consider one way to handle this paper in Figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1. Paper Writing Example

We can even use incentives to help us achieve the distal goal. How so? We might give ourselves a prize or reward (the incentive) after achieving each of the proximal goals. This might be the ability to watch one episode of our favorite television show after we finish part one of the main body (PG2). And the break from writing will help keep us fresh too.

3.3.1.3. Implementing the plan. Once your plan has been developed, it’s time to put it into action. We will see how this can occur in relation to behavior modification in Module 6. One common reason many people fail to start their plan is that they are waiting for the ideal time. If you wait for the perfect time to implement the plan there will never be one. Start it on a designated date, record along the way, and then check in to see how you are doing. How so?

3.3.1.4. Assessing our progress. Without assessing your plan, you will not know if it is working or not, or if you need to make changes to the plan. You can assess goal progress by looking at the data you have collected. You can also request feedback from others. As social support can serve as a reminder to make your goal-directed behavior, so too, can it be used to compliment a job well done or offer advice on how to improve your plan. You might learn exactly where you are going wrong and what you can do to get back on track with achieving your goal. This may sound like good advice but the necessity to monitor goal progress is supported by research and is a necessary self-regulation strategy (Harkin et al., 2016).

3.3.1.5. Success. When we achieve a goal, we feel satisfied, called valence. Our feeling of success is even greater when we complete a goal high up in our hierarchy and one that we deemed to be difficult to achieve. An example would be obtaining your Ph.D. This would be at the highest level of educational goals and the difficulty, well, speaks for itself. If getting a doctorate was easy a lot more people would have one. Interestingly, when I successfully defended my dissertation, thereby earning my Ph.D., I was happy, don’t get me wrong. But in the moment, I felt more a sense of relief and closure. Over a decade of striving, persisting, modifying plans, studying, stressing, etc. was finally over. I was done!

3.3.2. Goal Failure

3.3.2.1. What does failure look like? We set our hearts on finishing our goal. We write a clear and actionable goal statement. We develop a plan. Its implemented…but we are no closer to achieving our goal now then we were when we started. Many of us face this very issue with weight loss, your author included. Late in the spring of 2018 I embarked upon a clear weight loss goal with what I thought were manageable, and realistic, subgoals. Things started off well, but as happens with weight loss, I plateaued for a while. I stuck with it and finally started losing again. And then…flatline. My weight loss goals were stymied. Is this goal failure? Possibly and as noted earlier, I sought medical advice to figure out what to do. In Module 1 I pointed out that to engage in motivated behavior we need to have the knowledge. I may have been motivated but was not aware of the effect sugar was having on my body. I have that knowledge now, am competent, and motivated.

3.3.2.2. Why do we fail? We could fail at our goal for numerous reasons and The Huffington Post had a great article on 4/29/2015 concerning why we fail at our goals. Simply, ten reasons were given to include:

- Making excuses – It is easier to come up with reasons why we cannot do something than why we can or should. For many, time is the biggest excuse, and they might say they could not get to the gym that day because there just were not enough hours in the day.

- The why – Our motivation for the goal was not strong enough. Did we really want to achieve the goal or was an outside source driving us?

- Distractions and Priorities – Tied in with the excuses issue, we allow ourselves to be distracted at times when we really are not motivated to engage in the behavior at hand. Look at the definition of unmotivated again from Module 1.

- No clear plan – As the article says, “When we fail to plan, we plan to fail.” Even if we have a plan, it may not be as clear or realistic as we hoped it was.

- When the tough get going…we give up – Wait. That’s not how the expression ends. Isn’t it that ‘the going get tough’? Apparently, but not for all. Some goals will tax our resources heavily and we quit when we should keep pushing along.

For more reasons we quit, as these are just half of them, please visit the article at:

https://www.huffingtonpost.com/yvonne-kariba/10-reasons-we-fail-to-ach_b_7152688.html

3.3.2.3. A course correction? Now that we have established that we have failed and have an idea of why, what do we do? Well, we can always try again. If we fail again, then maybe it is time to quit and move on. Or maybe we do not want to abandon the goal but reduce its goal level, so it is not something we are immediately trying to achieve. Finally, we could revise the goal. Maybe instead of obtaining the Ph.D. we settle for getting our master’s degree. In my case, maybe 50 lbs. of weight loss in 5 months, or 10 lbs. a month, was too much. Should I reset my goal to focus on less weight loss or extend the time to achieve it? Maybe instead of indicating a new target weight at the end of each month, I just indicate the target weight and no more. This goes against most of the advice given in this module as if I am not specific enough about a timeframe, I will not feel a sense of urgency and likely return to bad habits. I think for me, the best approach is not to be too specific about time but reduce how much weight I should be losing each month. I thought about 2.5 lbs. a week was reasonable, but obviously it was not. So, a course correction is in order, and I have lost some weight, kept it off, and established good eating habits. Though my plan has not achieved the predicted success, it has achieved a different type of success that is worth focusing on. As goals go, remember that you may not always get what you were aiming for, but that does not mean it’s a total disaster. The glass is always half full, not half empty.

3.3.3. Final Thoughts…Task Completion – the Zeigarnik and Hemingway Effects

In the late 1920s, Bluma Zeigarnik and Maria Ovsiankina gave participants tasks to complete but interrupted them during some of the tasks. Zeigarnik (1927) found that the tasks that were remembered best were the ones participants were unable to complete and called it the Zeigarnik effect. This makes sense if you think about that to-do list you made for the day. At the end of the day, you are more likely to focus on the tasks that were not completed, especially if they were of high importance and needed to be done. This can lead to both rumination on the tasks and the loss of sleep (Syrek et al., 2017). Ovsiankina (1928) found that participants resumed these incomplete tasks even if there was no obvious benefit to themselves and speculated that this occurred because an internal pressure was created that necessitated its resolution or resuming and completing the task.

Fast forward to the present and the “near miss” phenomenon which suggests that if we are close to being successful at achieving our goal but fail to do so, we will want to try again so that we can avoid the regret that failure will surely produce (Reid, 1986). Termed the Hemingway effect, Oyama, Manalo, and Nakatani (2018) found that people are motivated to continue with a task if they believe they are close to completing it and know what needs to be done to complete it. Both conditions are important. The first condition is related to the near miss phenomena while the latter links to the expectancy-value theory, which states that our motivation to engage in a specific behavior is higher if we expect success at achieving a goal we value. The authors write, “…increased motivation to re-engage in the unfinished task would only occur when people can clearly see what more they need to do to finish it – thus supporting their expectation to succeed when they reinvest effort in completing the task.” Interesting.

Module Recap

When it comes to our world, we are motivated to set goals and try to achieve them. Goals can be large in scope, complex, and take planning. To aid in our success, incentives can be used and, oftentimes, we pursue more than one goal simultaneously. Goals may be ranked based on how important they are to us, how difficult they are, or how specific we can be about them. In the case of specificity, the more specific the better our planning can be. We are also more likely to achieve success if we are committed to our goal and break down larger goals into smaller components, called subgoals. Think of this as having the goal to write your term paper for a class. A term paper is a fairly time-consuming endeavor and just thinking about it can be unnerving for many students. But if we break the paper up into smaller components, these are less psychologically daunting and we are more likely to finish the whole paper and give it maximum effort. As we meet our subgoals, we can reinforce our hard work and dedication by allowing ourselves to do something fun. Finally, the paper is complete and we feel success. Sometimes goals are a bit too lofty, and we fail. This may require withdrawing or giving up on the goal, confronting the failure by formulating a new plan and/or acquiring some needed skill, or compromising and temporarily lower the goal in the hierarchy. No matter what strategy, research on the Zeigarnik effect shows that we will remember these incomplete tasks and the Hemingway effects shows that we will continue to try and achieve them if the end is near, and we know what we need to complete.

With that, we are finished with our discussion of goal motivation. Well, it will come up repeatedly throughout this book and again in Module 4 on stress and coping. Sometimes the stress we experience is self-imposed by having too many goals, too many high-level goals, feeling external pressure to complete them, or even external pressure to achieve success linked to high achievement motivation. These self-imposed stressors are linked to goals and can reduce our ability to effectively cope with stress. Goals also are important to a discussion of behavioral change in Module 6. Keep goals in mind as we round out Part II of this book.

2nd edition