Module 2: Emotion

Module Overview

In Module 1, I set a foundation for what motivation is so that the discussions to come are clearer for the reader – i.e., you! In Module 2, I will do the same, but in relation to emotion. Interestingly, many introductory books and texts on motivation often place this discussion near the end of the book or chapter but emotion and mood are discussed at various times throughout the earlier chapters. Students lack any real understanding of the significance of emotion and how it serves a motivating force in their lives, due solely to a misplaced chapter/content by the author(s), which may mean that the point of those earlier discussions is lost on them. I decided to present this information early in my text so that as you read the rest of the book, you have the necessary foundation. For instance, after Module 2, emotion and mood will come up again as we discuss goals (Module 3), stress and coping (Module 4), behavioral change (Module 6), personality (Module 7), religion (Module 9), health and wellness (Module 11), group processes (Module 12), and cognition (Module 13). Realistically, emotion will come up in every module, somewhere, but these were the modules I could quickly come up with examples for. I hope you enjoy this discussion and learn something you did not know.

Module Outline

- 2.1. Types of Affect

- 2.2. Characteristics of Emotion

- 2.3. The Physiology of Emotion

- 2.4. Expressing Emotion

- 2.5. Theories of Emotion

- 2.6. Is Emotion Adaptive?

- 2.7. Disorders of Mood

- 2.8. Emotional Intelligence

Module Learning Outcomes

- Differentiate what are affective states, moods, and emotions.

- Classify emotions through its dimensions.

- Identify physiological processes and the role of the nervous system in the experience of emotion.

- Clarify whether nature or nurture affect the expression of emotion.

- Describe research ascertaining the validity of the facial-feedback hypothesis and the existence of micro-expressions.

- Compare and contrast the three main theories of emotion.

- Clarify how positive emotion can be adaptive.

- Identify and explain the significance of disorders of mood.

- Clarify the significance of emotional intelligence (EI).

2.1. Types of Affect

Section Learning Objectives

- List, define, differentiate, and exemplify affective states, mood, and emotions.

- Define perceptual set.

- Clarify the three parts of an emotion, according to Watson.

In our everyday parlance, we use the term emotion for anything related to our affective state but this is an overextension of the term. What we mean by emotion may not actually be an emotion. So, to begin our discussion, let’s distinguish emotion from two other types of affect – affective traits and moods.

First, affective traits are stable predispositions for how we respond to our world and lead us to react to events we experience in specific ways. They are stable and can last a lifetime, once established. They include optimism/pessimism or neuroticism, to name a few.

Second, mood is an affective state that fluctuates over time. In terms of intensity, it is relatively mild and can last for hours, days, or weeks. We might describe our mood as being content, so-so, or irritable. Mood moderates how we perceive the events occurring around us. Moods can vary by season as in the example of Seasonal Affective Disorder or SAD for short. Also, you likely have heard about mood disorders such as depression or bipolar disorder. I will overview such mental disorders later in this module.

Finally, emotions are our immediate response to a situation that is personally meaningful. An emotion is very short in terms of duration but intense. Examples might be saying we are angry, elated, or afraid. We will spend much of this chapter covering emotions, but before we move on, let’s tackle an example of how the three affect us on a daily basis.

Let’s say our boss tells us that the company is downsizing and though that is bad, we are being kept on. To compensate for the loss of other employees, we will have to learn a new skill set. Oh yeah. We are not being paid more to do it. If our affective traits generally include optimism and being hardy, or being able to face change with confidence, and our mood is positive, we might still view the extra training negatively, but are only a bit upset. We might see it as a challenge and another line we can add to our resume. Or maybe being that we are in a good mood we have a neutral response to it and just sign up for the training. Of course, we could see it as a good thing from the start. No matter the scenario, our emotional response could be slightly negative, neutral, or positive given our generally optimistic state and being in a good mood. It’s possible our motivation for working (intrinsic vs. extrinsic) will be a moderator here.

Now what if we are still optimistic and hardy, but in a bad mood? We might have a stronger negative reaction than we did when in a good mood, assuming we had one, but with some time come to see it in much the same way – with optimism and as a challenge. Our bad mood does likely cause us to react in an uncharacteristic way initially, but with time our stable traits re-emerge.

Let’s say now that we are pessimistic and easily overwhelmed in terms of our affective traits, and in a good mood currently. We would be upset about the training and see it as unfair. The stressor could lead to frustration, feeble attempts at self-regulation resulting in our communication of a less than favorable attitude toward or boss at work and maybe online (i.e., Facebook). Though in a good mood when told about the training, this likely shifts to a bad mood given our generally negative disposition. The response may not be as strong since we were in a positive mood when told.

Finally, we are pessimistic and in a bad mood. We are VERY upset about the training and would likely be open about it at work. Of course, this could have serious implications for any future promotions and/or raise questions about our job security. Bad mood and negative disposition mean we are very unhappy and willing to share that with all. Misery loves company.

So, we entered the scenario with specific, stable predispositions as to how we react to events in our world and what decisions we make in terms of the activities we partake in. Despite this, a good or bad mood can initially cause us to react to the stressor in a very uncharacteristic way (i.e., our emotional response). Luckily, the emotion is brief and acute, affected by the mood we are in. Once over and we have had time to reassess the situation, called reappraisal, we may decide our boss ordering us to take on additional responsibilities is not as bad as first thought (assuming we had positive affective traits underlying our behavior from the start). If we had a negative predisposition no amount of reappraisal may help.

There is one more thing to think about. Consider that though John may be in a good mood and an optimistic person, the way John’s boss communicated the demand to him (i.e., in order to keep his job, he will have to learn a new skill set and will not be paid extra to do it) may have affected his reaction too. This very well could be considered an example of pull motivation!

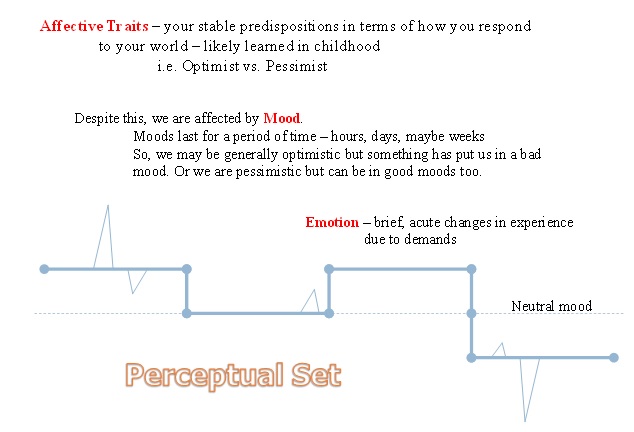

Figure 2.1. Examining the Interaction of Affective Traits, Mood, and Emotion

Notice in Figure 2.1. the term perceptual set, which is defined as the influence of our beliefs, attitudes, biases, stereotypes, and … well, mood, on how we perceive and respond to events in our world! We will see evidence of this all throughout the course. The line across the center of the figure represents a neutral mood and so above it is a good mood and below it a bad one. The spikes represent our emotional response and, as you see, can vary quite a lot. A positive emotion would be a spike above the line while a negative emotion is below the line. On the far-left notice that we are in a good mood and our positive emotional response is heightened. The negative emotion we experience to an event is not as extreme as the example on the far right when we are in a bad mood. Also, the positive emotion is not as strong on the far right because we are in a bad mood. In the neutral example in the middle, our positive reaction is mild to moderate since we are sort of middle of the road with our mood. This is just one way to view the three types of affect and their effect on our daily lives.

Before we move on, I want to be clear you understand the difference mood and emotion. We will discuss both quite a lot throughout this module (and book), and affective traits sound a lot like emotional personality traits, which will be discussed also (Module 7). But for our purposes, mood and emotion are what we are most familiar with.

John B. Watson said that emotions have three parts:

- The objective, stimulus situation

- Overt bodily response

- Internal, physiological changes

Essentially, we have to sense (through sensation and our eyes, ears, nose, tongue, or skin – the sensory organs) an event in our environment (the objective, stimulus situation) which leads to a response which others can see (what makes the bodily response overt or observable). What governs our sensation of the stimulus and eventual response are actions of our central and peripheral nervous systems, endocrine system, muscular and skeletal systems, etc. (the internal, physiological changes). Think back to your introductory psychology course or courses you took later where you discussed sensation, neural impulse, brain structures and their functions, perceptual processes, and the sending of commands to various parts/systems of the body. This process (i.e., communication in the nervous system) is what Watson was essentially capturing. The response we make is automatic and a result of our perception of the environmental stimuli. We can view our emotion, or someone else’s, from facial expressions, tone, gestures we might make, and other nonverbal cues, such as body language.

Later in this module, mood will be discussed in more detail. If you are interested in clinical psychology, then you are likely familiar with mood disorders! Until then, moving on.

2.2. Characteristics of Emotions

Section Learning Objectives

- Clarify how emotions are temporary.

- Clarify how emotions are positive and negative.

- Describe the intensity of an emotion.

- Explain how emotion is linked to appraisal.

- Clarify and exemplify how emotions change one’s thought processes.

Now that we have a working knowledge of what emotions are, and how they differ from affective states and moods, let’s dive into what the characteristics of emotions are. Emotions consist of five main characteristics – they are temporary, positive or negative, vary in intensity, are based on one’s appraisal of the situation, and alter our thought processes.

2.2.1. Temporary

As we already discussed, compared to affective states and mood, emotions last for a very short period of time since they are a response to some actively occurring, or recently occurred, environmental event. They have a clear beginning and end, as in our example in Section 2.1. Our emotional response to having to learn new skills for our job happened as soon as we received the news and then ended shortly thereafter, allowing us time to reappraise the situation and see if it was as bad as we thought it was.

2.2.2. Positive or Negative

It should be no surprise to find out that we can experience positive or negative emotions. Winning the state title in baseball will leave the winning team happy or ecstatic while the losing team is disappointed. The 2018 College World Series (CWS) pitted Oregon State against Arkansas and clearly exemplifies this point in dramatic fashion. After falling in the first game to Arkansas, Oregon State won the last two games. But Game 2 was incredible in terms of how they won. With 2 outs in the top of the 9th and down by a run, an Arkansas infielder dropped what should have been a routine fly ball in foul territory to end the game and claim their first ever CWS title. OSU then rallied for three runs (keep in mind that it was 2 outs still) and won the game in 9 innings, 5-3. This led to Game 3 in a best of three series. Oregon dominated the game offensively, defensively, and through masterful pitching, and won 5-0 to claim its third such title. Emotions, positive on the OSU side and negative on the Arkansas side, ran high as the 2018 college baseball season came to a close.

2.2.3. Intensity

In Section 2.2.1 we established that emotions last a short period of time, reflecting on its duration. Recall from Module 1 that behavior is characterized by frequency, duration, and intensity. It should be no surprise that an emotional behavior is characterized also in the same way. In terms of intensity, we experience different levels of an emotion. We might be annoyed, irked, angry, or furious in relation to our sibling taking our favorite toy without permission. Getting an A on a paper may make us feel content, happy, or ecstatic, depending on the difficulty of the assignment, how important a good grade was to us, and other factors to be discussed in Module 3. Recall from Section 2.1 that mood moderates this emotional expression. In other words, it affects how intense our emotional response is. Intensity is important as many emotion researchers such as Plutchik (2003) have identified as few as eight primary emotions – anger, joy, trust, fear, sadness, surprise, disgust, and anticipation. Each of these eight emotions can vary in intensity though, such as the examples given above, and expands our emotional vocabulary.

2.2.4. Based on One’s Appraisal of the Situation

There is an expression that says perception is 90% of reality. I have always said that it is really 100% of a person’s reality. Notice the word person in there. What we perceive to be true may not be what really happened. As you learned in Section 2.1, perceptual set affects our interpretation of events due to the influence of past experiences we have had, current prejudices or stereotypes we hold, and our mood, whether good or bad. All of this explains why we can witness the same event at two different times and have two different interpretations of it. Heck, this can happen in the same day. Let’s say we wake up early in the morning and after getting ready for the day step into the kitchen only to find dishes left by our roommate the night before. He or she has already left for the day and so cannot do anything about them right now. You slept well and are optimistic about the day so you don’t get upset about this (though it is a recurring problem with your roommate and a behavior you would very much hope he/she changes). You go off to classes but have a pop quiz in one class and are returned a paper in another class, neither of which you did well on. This sours your mood and once finished with your last class, you head home. It is obvious no one has been there all day but upon seeing the dishes in the sink again, you become furious. Your emotional reaction this morning was neutral at the sight of the dishes but just hours later, it has become highly negative. Again, your roommate never returned home during the day which would have meant he/she had a chance to clean them but chose not to. This shows that our emotions are determined by our appraisal of a good or bad event, but also, that this appraisal is not set in stone. Events of the day can change it.

2.2.5. Alters Thought Processes

Our appraisal may not always be changed by something as simple as mood, which can also shift back in the other direction. Consider that after relaxing from the tough day and destressing, we are no longer upset about the dishes, just in time for our roommate’s return home and the avoidance of a nasty altercation. Sometimes though, stimuli that we experience changes us in unexpected ways and can alter our thoughts, beliefs, and attitudes at a fundamental level.

It was September 11, 2001 and I was an undergraduate at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, completing my Bachelor’s degree in Psychology. The day was going along like any other and I was finishing up my classes for the morning, at the time sitting in Psychology of Gender Differences. Suddenly, my phone vibrates. I check to see who it was and notice my mother was calling. Since I could not actually answer the call, I silenced it. Moments later I received another call from her and proceeded to silence it again. This continued several more times over the next 15 minutes, obviously piquing my curiosity. Why would she call so many times when she knew I was at school? Class finally came to an end and I listened to one of the several voicemails she left. Basically, they all went something like this, “Lee. This is Mom. You have to look at the television. The Trade Center Towers in New York have fallen because of planes flying into them. We are under attack.” Now, my mother has a tendency to exaggerate so I assumed this was another instance of that. I walked over to the Student Union building to see if the televisions had anything about this “attack.” What I saw were hundreds of students standing around, their eyes glued to the television, and would soon come to learn the veracity of her statements. In fact, it was much worse than she even thought at the time. Around the county and world, millions of people were witnessing the same event at the same time. While this was occurring, and all were horrified at the chain of events and the sheer loss of life, thoughts about the Muslim community were changing. Most were distraught; many were looking to express solidarity with others; while some were angry.

Research has confirmed a change in how Muslims were perceived pre- and post-9-11, and subsequent actions taken against them due to these shifting attitudes. Since 9-11, Muslims have been perceived as violent and untrustworthy (Sides and Gross, 2013), there has been lingering resentment and reservations about Arab and Muslim Americans (Panagopoulos, 2006), and Muslims experienced a period of violence, elevated harassment, political intolerance, and workplace discrimination in the U.S. in the weeks and months after the attacks (Abu-Raiya, Pargament, & Mahoney, 2011; Disha, Cavendish, & King, 2011; Morgan, Wisneski, & Skitka, 2011) which led to poor birth outcomes in Arabic-named women (Lauderdale, 2006). In fact, Arab Muslim recent immigrant communities in Canada have themselves experienced a rise in perceived discrimination and psychological distress post 9-11 (Rosseau et al., 2011). It should be noted that threat perception is cited as the single most important predictor of in-group attitudes toward out-group members and so people who feel threatened by Muslims are more likely to associate negative characteristics to the group (Wike & Grim, 2010). But this works the same for all groups perceived as a threat, not just Muslims. For instance, Golebiowska (2004) found that intolerance of religious minorities was linked to perceived threats to Poland’s independence.

On a positive note, this shift is not present in all members of the in-group in relation to an out-group member. Johns, Schmader, and Lickel (2007) found that identification with being an American was predictive of greater levels of shame and a desire to distance oneself from the in-group, when negative behavior was committed by another member of the group. And some in-group members focus their energy into positive actions, such as donating blood or money to charities and flying the American flag (Morgan, Wisneski, & Skitka, 2011). Also, Swedish researchers reported no increase in workplace discrimination after 9-11 (Aslund & Rooth, 2005).

2.3. The Physiology of Emotion

Section Learning Objectives

- List the main parts of the nervous system and their role in emotion.

- Identify and clarify the role of key brain structures in emotion.

2.3.1. The Nervous System

To fully understand the physiology or biology of emotion, we need to first understand how the nervous system works. Essentially, the nervous system breaks down into two main parts: the central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral nervous system (PNS). The CNS is the control center for the nervous system, which receives, processes, interprets, and stores incoming sensory information. It consists of the brain and spinal cord. The PNS consists of everything outside the brain and spinal cord and handles the CNS’s input and output. It divides into the somatic and autonomic nervous systems. The somatic nervous system allows for voluntary movement by controlling the skeletal muscles and carries sensory information to the CNS; the autonomic nervous system regulates the functioning of blood vessels, glands, and internal organs such as the bladder, stomach, and heart, and consists of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. It is the sympathetic nervous system which is involved when a person is intensely emotionally aroused. It provides the strength to fight back or to flee (fight-or-flight instinct) by bringing about an increase in blood flow, blood pressure, heart rate, and breathing and dilating our pupils. Unnecessary functions, such as salivation and digestion, are slowed or inhibited and our bladder relaxes. This system also stimulates the release of adrenaline, noradrenaline, and the neurotransmitter norepinephrine (Berridge, 2007). The parasympathetic nervous system calms the body after sympathetic arousal. It constricts our pupils and drops heart rate, blood pressure, and respiration while returning digestion to its pre-arousal levels and stimulating salivation.

2.3.2. The Brain

In terms of the brain and its role in emotion, we need to look no further than the limbic system and the actions of the amgydala. Previous research has shown that the amygdala plays a key role in our ability to recognize emotional expressions or words with emotional connotations, emotional learning and memory, and emotional influences on attention and perception (Armony, 2013; Phelps & LeDoux, 2005; Anderson and Phelps, 2001). A more recent study showed that the amygdala is involved in encoding the subjective judgment of emotional faces (Wang et al., 2014).

In addition to the amygdala, a separate line of research implicates the pyramidal motor system, which controls voluntary movement, and the extrapyramidal motor system, which controls involuntary movements such as those associated with genuine emotion. Smiles that reflect genuine happiness (i.e., Duchenne smiles) are involuntary and under control of the latter system while fake smiles (i.e., non-Duchenne smiles) are controlled by the former. Hopf, Muller-Forell, and Hopf (1992) found that patients with damage to the pyramidal motor system could not fake a smile but were able to produce facial expressions during genuine emotion, while those with damage to the extrapyramidal motor system could make facial expressions willingly but did not show emotion when its expression would be genuine.

Do the different hemispheres of the brain control different aspects of emotion? It appears so and research has shown that the left hemisphere is involved in positive emotions such as happiness, while negative emotions, such as disgust, rely on the right hemisphere (Smith & Cahusac, 2010; Harmon-Jones et al., 2004; Davidson & Irwin, 1999; Ahern & Schwartz, 1985; Ahern & Schwartz, 1979). The right hemisphere has also been found to recognize emotional stimuli quicker and more accurately than its counterpart (Ley & Bryden, 1982). If you think about evolution and the survival of the fittest, this makes a great deal sense. Why is that?

2.4. Expressing Emotion

Section Learning Objectives

- Argue for the nature or nurture perspective in relation to emotion.

- Define and describe the facial feedback hypothesis and evidence for it.

- Define microexpressions and clarify their importance.

2.4.1. Emotion – Nature vs. Nurture

The nature-nurture debate refers to the influence of genes and heredity (i.e., nature) or the environment (i.e., nurture) on any behavior, whether covert or overt. In terms of our discussion in Module 2, we want to discern whether emotion is a product of nature or nurture. Charles Darwin (1872/1965) stated that the facial expressions of humans are innate or inborn, and not learned. Hence, Darwin advocated the nature perspective. He believed that if a facial expression existed today, it was because it served some adaptive advantage and was effective at conveying emotion. In fact, research shows that environmental stimuli produce similar facial expressions across cultures (Hejmadi, Davidson, & Rozin, 2000; Zajonc, 1998). Ekman, Sorenson, and Friesen (1969) found that individuals living in literate (i.e., U.S., Japan, Argentina, and Chile) or illiterate cultures (i.e., the Fore tribe of Papua New Guinea) had a high degree of agreement as to what emotion was expressed by different facial expressions, though the literate cultures did perform better.

So, does the question end with this answer – that emotion has a genetic/evolutionary basis? Not likely, as there is considerable evidence to support a nurture perspective, too. In fact, Ekman even said that not all emotional expressions are innate (Ekman, 1993), but some are learned through socialization. The society we live in has standards or rules for when, where, and how our emotions can be communicated, called display rules (Ekman, Friesen, & Ellsworth, 1972). These are taught as early as infancy (Malatesta & Haviland, 1982) and children demonstrate understanding of these rules by the preschool years (Banerjee, 1997). Young children have reported expressing sadness and anger at significantly higher levels than older children, girls are more likely than boys to express sadness and pain, and children demonstrate emotional self-regulation when in the presence of their peers more than with their parents (Zeman & Garber, 1996)., In school settings, they report using display rules related to anger and aggression more when around teachers than peers (Underwood, Coie, & Herbsman, 1992). Emotion display rules even make their way into the workplace. Grandey et al. (2010) found that employees feel it is fine to express anger at other employees, can limitedly express it at supervisors, but completely suppress it with customers. Cross-culturally there are differences. French employees found it to be more acceptable to express anger at customers while American employees advocate expressing happiness at customers. Though many countries follow the “service with a smile” guideline, this belief is most strongly held in the United States. An earlier study produced similar results and found that in the United States, professionalism is most important, both positive and negative emotions need to be displayed appropriately, and the only proper display of negative emotions is to mask them (Kramer and Hess, 2002). Finally, Safdar et al. (2009) conducted a comparison between students in the United States, Canada, and Japan and found that Japanese display rules allow for the display of the emotions of anger, contempt, and disgust much less than the two Western samples, and compared to Canadians, Japanese display positive emotions less. Gender differences were evident but follow the same pattern across all three cultures – men expressed anger, contempt, and disgust more than women, while women displayed happiness and powerless emotions, such as sadness and fear, more than men.

2.4.2. Facial-feedback Hypothesis

It is possible to assume that our facial expressions not only reflect our emotions but influence them too. The facial-feedback hypothesis states that our facial muscles send information to the brain which aids in our recognition of the emotion we are experiencing. Soussignan (2002) found that participants who displayed Duchenne smiles (real smiles) reported a more positive experience when viewing humorous cartoons and pleasant scenes. Similarly, lifting the cheeks upward, as opposed to lowering them, has the effect of making participants feel happier (Mori & Mori, 2009). Facial muscles also provide reliable information to the brain in relation to fear-evoking stimuli (Dimberg, 1986) and sadness (Mori & Mori, 2007). Could botox injections actually make you happier? Researchers suggest just that and state that botox injections for upper face dynamic creases can reduce negative facial expressions more than positive ones, and lead the patient to feel less fearful, angry, or sad (Alam et al., 2008).

2.4.3. Microexpressions

Microexpressions are facial expressions that are made briefly, involuntarily, and last on the face for no more than 500 milliseconds (Yan et al., 2013). It is possible that being able to read them could reveal a person’s true feelings on a matter (Porter & Brinke, 2008) and evidence exists for the ability to train people to read these facial expressions (Matsumoto & Hwang, 2011). This skill would be particularly useful for law enforcement officials (Ekman & O’Sullivan, 1991).

2.5. Theories of Emotion

Section Learning Objectives

- Compare and contrast the James-Lange, Cannon-Bard, and Schachter-Singer theories of emotion.

Over the decades, several theories have been proposed to explain our emotional response to stimuli in our environment, particularly where fear is concerned. Consider how you might respond to someone running a red light as you approach the intersection. Of course, you know you will be pretty shaken by it and will take steps to avoid a collision, but in what order do these events occur? Let’s explore this scenario closer. By the way, I am choosing this example as I write Module 2 in late July 2018 because this happened to me two days ago.

2.5.1. James-Lange Theory

William James (1890/1950) and Carl Lange (1922) said that an emotion occurs after a physiological reaction to an event in our environment. We will see the person running the red light, take actions to avoid the collision, and then become upset. To keep with driving examples, what do you do when you see a police officer on the side of the road facing your direction? Most people slow down and then become nervous wondering if they were speeding, and if the cop knew they were speeding, if the cop would pull them over and give a ticket. So, our emotion follows our action (the physiological response). James-Lange also said that each emotion has a distinct physiological profile that sets it apart from other emotions. What does it feel like to be in love? Do your knees get weak? Do you have butterflies in your stomach? Do you ache to be with the person? If so, these are unique physiological reactions to being in love. What do you feel like when angry? I bet any changes in heart rate, sweating, breathing, etc. are different from being in love. We sense the stimulus in our environment, perceive its emotional importance (i.e., through the amygdala), undergo physiological changes, and then produce an emotion.

Think about this….

The James-Lange theory says each emotion has its own distinct physiological profile as you read about for love. I bet you have experienced this before in new romantic relationships. But do these physiological manifestations of being in love last forever? Do they fade with time, and if so, what does this mean for the James-Lange theory of emotion?

2.5.2. Cannon-Bard Theory

Walter Cannon (1927; 1932) disagreed with James about each emotion having its own physiological profile and instead proposed, along with Philip Bard (1934), that the emotion and physiological response occur simultaneously. So, when the car runs the red light, we see this, which activates the thalamus in our brain. Our autonomic nervous system, cortex, and hypothalamus are next alerted. It is the cortex that produces the emotion we experience and our hypothalamus causes the body’s arousal to deal with the threat, through actions of the sympathetic nervous system (which is part of the ANS) or the flight-or-fight response. Upon seeing the car run the red light, we experience bodily arousal, put our foot on the brake, and experience terror of almost having a collision. According to Cannon-Bard, the subjective feeling or emotion is not dependent on physiological changes, and the CNS directly experiences the emotion, even if other systems of the body do not.

2.5.3. Schachter-Singer Two-Factor Theory

Stanley Schachter and Jerome Singer proposed the two-factor theory of emotion during the early 1960s. They asserted that any display of emotion first begins with an assessment of our physiological reaction or bodily response but since this reaction can be similar between emotional states (i.e., though we might experience fear at seeing the car go through the intersection, we might also experience surprise, anger, or even excitement if we drive a race car for a living), another step is needed. Simply, we have to make a cognitive appraisal of the situation which allows us to identify which emotion we are experiencing. Seeing the car run the red light causes a physiological response in terms of being aroused. The situation is assessed to determine the source of this arousal, which is the car running the red light, and then the fear is identified as the emotional response to the sequence of events. So, the two cognitive factors Schachter and Singer assume are the initial sensation and perception of the stimulus that causes our physiological arousal and then the interpretation of that response as a specific emotion. In a way, they agreed with the James-Lange theory but believed it needed some refinement.

2.6. Is Positive Emotion Adaptive Too?

Section Learning Objectives

- Recall the adaptive advantage of fear.

- Define the broaden-and-build model and clarify why it is adaptive.

Recall that in Module 1.5.2.2 we discussed fear serving an adaptive advantage, and that we are biologically prepared to learn some associations over others (Seligman, 1971). Of course, fear is a type of negative affectivity, but positive affectivity can be adaptive too. How so?

According to the broaden-and-build model (Fredrickson, 1998, 2001), positive emotions widen our cognitive perspective, aid us in thinking more broadly and creatively, build resources, and help us acquire new skills to face the challenge. Negative emotion, on the other hand, promotes a narrow way of thinking. In a study of 138 college students, Fredrickson and Joiner (2002) found that initial positive affect predicted improved broad-minded coping and that initial broad-minded coping predicted positive affect but not reductions in negative emotion. The authors took this as evidence that positive emotions cause upward spirals toward enhancing one’s emotional well-being. Positive emotions have also been shown to broaden the scope of attention, while negative emotions narrow thought-action repertoires (Fredrickson and Branigan, 2011). Finally, gratitude has been found to broaden and build (Fredrickson, 2004) and happiness is linked to increased life satisfaction (Cohn et al., 2009). So, both positive and negative emotions aid us in survival, though negative emotions are most effective at dealing with immediate threats in our environment.

2.7. Disorders of Mood

Section Learning Objectives

- Define mental disorders.

- Identify one such classification system for mental disorders.

- List and describe bipolar disorders.

- List and describe depressive disorders.

As we wind down our discussion of emotion and mood, I wanted to at least call attention to the fact that where these topics are concerned, they intertwine with clinical psychology and mental disorders. A more exhaustive discussion of mood disorders can be found in an abnormal psychology course.

2.7.1. Overview of Mental Disorders

Mental disorders are characterized by psychological dysfunction which causes physical and/or psychological distress or impaired functioning and is not an expected behavior according to societal or cultural standards. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (APA, 2013), is one way of classifying mental disorders. For example:

- Neurodevelopmental disorders – A group of conditions that arise in the developmental period and include intellectual disability, communication disorders, autism spectrum disorder, motor disorders, and ADHD

- Schizophrenia Spectrum – Disorders characterized by one or more of the following: delusions, hallucinations, disorganized thinking and speech, disorganized motor behavior, and negative symptoms

- Bipolar and Related – Characterized by mania or hypomania and possibly depressed mood; includes Bipolar I and II, cyclothymic disorder

- Depressive – Characterized by sad, empty, or irritable mood, as well as somatic and cognitive changes that affect functioning; includes major depressive and persistent depressive disorders

- Anxiety – Characterized by excessive fear and anxiety and related behavioral disturbances; includes phobias, separation anxiety, panic attack, and generalized anxiety disorder

- Obsessive-Compulsive – Characterized by obsessions and compulsions and includes OCD, hoarding, and body dysmorphic disorders

- Trauma- and Stressor- Related – Characterized by exposure to a traumatic or stressful event, PTSD, acute stress disorder, and adjustment disorders

And there are 12 other categories mental disorders fall under. For our purposes, we will address disorders in the bipolar and depressive disorders categories since they relate to the topic of mood.

2.7.2. Bipolar Disorders

According to the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) bipolar disorder, “is a brain disorder that causes unusual shifts in mood, energy, activity levels, and the ability to carry out day-to-day tasks.” It manifests itself in one of four ways. First, Bipolar I disorder has manic episodes that last at least 7 days and usually, depressive episodes occur lasting about 2 weeks. Bipolar II disorder, in contrast, is characterized by depressive and hypomanic episodes and does not include the manic episodes of Bipolar I. Cyclothymic disorder or cyclothymia has numerous periods of hypomanic and depressive episodes lasting for at least two years.

In general, manic episodes are characterized by feeling high or elated, being irritable, having trouble sleeping, believing many things can be done at once, and doing risky things. Depressive episodes, on the other hand, are characterized by feeling sad or down, losing interest in pleasurable tasks, being forgetful, feeling tired, and decreased activity levels.

2.7.3. Depressive Disorders

All people experience depression from time-to-time. The actual experience of depression is not a problem, unless it lasts at least two weeks, affects functioning in more than one domain in life, and presents troubling symptomology such as those described above under depressive episode and possibly suicidal ideation. Its most serious form is major depressive disorder (MDD) though some people experience what is called persistent depressive disorder or dysthymia. Essentially, MDD lasts a short period of time (about two weeks) but is intense while dysthymia is milder but lasts at least two years.

Other forms of depression include postpartum depression or feelings of extreme sadness, exhaustion, and anxiety after the birth of a baby, and which make it difficult for the new mother to adequately care for her baby. Psychotic depression is when severe depression occurs at the same time as psychosis or having false beliefs (delusions) or seeing or hearing things that are not there (hallucinations). Finally, in seasonal affective disorder (SAD), depression occurs usually during the winter months, when there is less natural sunlight, but lifts in the spring. Individuals suffering from SAD experience weight gain, increased sleep, and social withdrawal.

For more on bipolar or depressive disorders, please visit:

https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/index.shtml

You can also visit the Abnormal Psychology OER which is part of the Discovering Psychology series from Washington State University: https://opentext.wsu.edu/abnormal-psych/

2.8. Emotional Intelligence

Section Learning Objectives

- Define emotional intelligence (EI).

- List and discuss its four core skills and two primary competencies.

- Clarify what research says about EI and its benefit.

Emotional intelligence or EI is our ability to manage the emotions of others as well as ourselves and includes skills such as empathy, emotional awareness, managing emotions, and self-control. According to a 2014 Forbes article by Travis Bradberry, EI consists of four core skills falling under two primary competencies: personal and social.

First, personal competence focuses on us individually and not our social interactions. Through personal competence, we are self-aware or can accurately perceive our emotions and remain aware of them as they occur. We also can engage in self-management or using this awareness of our emotions to stay flexible and direct our behavior to positive ends.

Second, social competence focuses on social awareness and how we manage our relationships with others. Through it, we can understand the behaviors, moods, and motives of others. This allows us to improve the quality of our relationships. In terms of social awareness, we pick up on the emotions of others to understand what is going on. Relationship management allows us to be aware of the emotions of others and ourselves, so that we can manage interactions successfully.

EQ is not the same as IQ or intelligence quotient as EI can be improved upon over time while IQ cannot. This is not to say that some people are not naturally more emotionally intelligent than others, but that all can develop higher levels of it with time.

For more from this article, please visit:

https://www.forbes.com/sites/travisbradberry/2014/01/09/emotional-intelligence/#84838541ac0e

How do we effectively use emotional intelligence? Mayer and Salovey (1997) offer four uses. First, flexible planning involves mood swings, which cause us to break our mindset and consider other alternatives or possible outcomes. Second, EI fosters creative thinking during problem solving tasks. Third, the authors write that “attention is directed to new problems when powerful emotions occur.” Attending to our feelings allows us shift from one problem to a new, more immediate one (consider that this can be adaptive too). Finally, moods can be used to motivate persistence when a task is challenging. Anxiety about a pending test may motivate better preparation or concern about passing preliminary examinations may motivate a graduate student to pay extra careful attention to details in the research articles he/she has been assigned.

Utilizing a sample of 330 college students, Brackett, Mayer, and Warner (2004) found that women scored higher than men on EI and that lower EI in males was associated with maladjustment and negative behaviors such as illegal drug and alcohol use, poor relationships with friends, and deviant behavior. Individuals scoring higher in the ability to manage emotions were found by Lopes, Salovey, and Staus (2003) to report positive relations with others, report fewer negative interactions with their close friends, and to perceive greater levels of parental support. They also found that global satisfaction with relationships was linked to effectively managing one’s emotions, the personality trait of extraversion (positive correlation), and was negatively associated with neuroticism. In terms of the academic performance of students in British secondary education, those high in EI were less likely to have unauthorized absences or be excluded from school and demonstrated greater levels of scholastic achievement (Petrides, Frederickson, & Furham, 2004), while EI is also shown to be related positively to academic success in college (Parker, Summerfeldt, Hogan, & Majeski, 2004).

Finally, Ciarrochi, Deane, and Anderson (2002) investigated the relationship of stress with the mental health variables of depression, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation. They found that stress was related to greater reported levels of the three mental health variables for those high in emotional perception and suicidal ideation was higher in those low in managing other’s emotions.

Module Recap

Well, that’s it. You now have a foundation to understand both the psychological constructs of motivation and emotion which will serve you well in the discussions to come. In terms of Module 2, I distinguished three types of affect – affective states, mood, and emotion – and then proceeded to list the dimensions of emotions. Well, some of them at least. Depending on where you look, other dimensions might be identified. As with all forms of behavior, emotional behaviors have a physiological cause and so we discussed the nervous system and role of the brain in producing the experience we call emotion. Do emotions arise from nature or nurture? The answer is both and we explored this through the universality of facial expressions but also the existence of display rules in society. We also discussed how the expression of emotion is exemplified by the facial-feedback hypothesis and the existence of microexpressions. Three main theories of emotions were compared and then a case was made for how positive emotions are just as adaptive as negative emotions. Well, maybe the latter is a bit more important for survival, but positive emotions play their part too. Finally, we discussed disorders of mood and emotional intelligence and its uses for our life.

With this module now complete, it may be time for an exam depending on how your instructor is testing the material. Whether or not you will have an exam, I have set the stage in Part I and we will now move to a group of interesting, interrelated topics in Part II – goals, stress and coping, the economics of motivated behavior, and the motivation to change.

I sincerely hope you are enjoying learning about motivation and emotion so far and see how this topic is intertwined in all that you have learned about psychology in your academic career. If not, you will understand soon.

2nd edition