Module 13: Motivation and Cognitive Psychology

Module Overview

We now turn our attention to sources of internal motivation. Module 13 will discuss cognitive process and how they relate to motivated behavior. Our discussion will cover perception, attention, memory, problem solving, reasoning, and learning. Each can be discussed in much more detail than given here but this is to provide you with some understanding and connections between cognitive psychology and motivation. Bear in mind that for every overt or observable behavior you see, there is a series of physiological and cognitive changes controlling it. In Module 13 we dive into cognitive and in Module 14 we will discuss physiological.

Note to WSU Students: The topic of this module overviews what you would learn in PSYCH 490: Cognition and Memory and PSYCH 491: Principles of Learning at Washington State University.

Module Outline

- 13.1. Perception: Motivated to Add Meaning to Raw Sensory Data

- 13.2. Attention: Motivated to Commit Cognitive Resources

- 13.3. Memory: Motivated to Retain and Retrieve Information

- 13.4. Problem Solving: Motivated to Find Solutions

- 13.5. Reasoning: Motivated to Make Good Decisions

- 13.6. Motivated to Learn…and at Times, Unlearn/Relearn

Module Learning Outcomes

- Clarify why we are motivated to perceive our world.

- Explain why we might attend to some events but not others.

- Describe the utility of retaining and retrieving information.

- Clarify types of motivated behavior we might engage in to solve a problem.

- Explain how we go about making good decisions and what form cognitive errors can take.

- Differentiate the different models for how we learn and clarify how each motivates behavior.

13.1. Perception: Motivated to Add Meaning to Raw Sensory Data

Section Learning Objectives

- Define sensation, receptor cells, and transduction.

- Define perception.

- Outline Gestalt principles of perceptual organization.

Before we can discuss perception, we should first cover the cognitive process that precedes it, sensation. Simply, sensation is the detection of physical energy that is emitted or reflected by physical objects. We sense the world around us all day, every day. If you are sitting in a lecture, you see the slides on the screen and hear the words coming from the professor’s mouth. As you sit there, you are likely smelling scents from your classmates, hopefully pleasant ones. You might be chewing gum and tasting its flavors. And your clothes brush up against your skin as you move in your seat. These events are detected using our eyes, ears, mouth, nose, and skin and as you will see in Section 13. 3 are sent to sensory memory first. The cells that do the detecting in these sensory organs are called receptor cells. I think it is worth noting that the physical energy is converted to neural information in the form of electrochemical codes in the process called transduction.

So, we have a lot of sensory information going to the brain via the neural impulse. What do we do about it? That is where perception comes in, or the process of adding meaning to raw sensory data. An analogy is appropriate here. When we collect data in a research study, we obtain a ton of numbers. This raw data really does not mean much by itself. Statistics are applied to make sense of the numbers. Sorry. I did not mean to use the s-word in this book. Anyway, sensation is the same as the raw data from our study and perception is the use of statistics to add meaning. You might say we are motivated to engage in the process of perception so that we can make sense of things.

Our perception of a stimulus can vary though….even in the same day. How so? Perceptual set accounts for how our prejudices, beliefs, biases, experiences, and even our mood affect how we interpret sensory events called stimuli. Over the last 10 modules we have discussed many ways that our perception can be affected (and defined this term in Module 2). Consider how we form our attitudes (from Module 12), how life events shape who we are (from Module 10), how we learn prejudices (from the upcoming Module 15), how our reasoning can be biased (to be discussed later in this module), how our worldviews affect perception (from Module 9), the effect of personality (from Module 7), or how satisfying our psychological needs or being deterred from doing so may affect our interpretation of events (from Module 8). What if we fail to achieve our goal? How might this frustrate us and lead to a change in mood (Module 3)? What if the costs of motivated behavior are too high (Module 5) or we are experiencing stress, which directly impacts how we perceive the world (Module 4)? What if we are ill and our health and wellness are compromised (Module 11) or finally, we are trying to change our behavior and having difficulties due to not knowing how to make the change or not having the skills to do it (Module 6)? These are examples from everything we have covered in this book so far of how our perception of events can be affected…and within a day, as Module 2 shows. One final example from health psychology will demonstrate this point. You wake up one morning feeling good but by afternoon are coming down with a cold and by the evening feel crappy. Consider how you might deal with your kids differently as the day goes on.

There is quite a lot that can be discussed in relation to perception, but I will focus our attention on Gestalt principles of perceptual organization. Gestalt psychology arose in the early 1900s in response to ideas originally proposed by Wilhelm Wundt in Germany and furthered by Edward Titchener and his system called Structuralism in the United States. The Gestalt psychologists were against the notion that perceptions occurred simply by adding sensations. They instead asserted that the whole is different than the sum of its parts. Their principles include:

- Figure-ground – States that figure stands out from the rest of the environment such that if you are looking at a field and see a horse run across, the horse would be the figure and the field would be ground.

- Proximity – States that objects that are close together will be perceived together.

- Similarity – States that objects that have the same size, shape, or color will be perceived as part of a pattern

- Closure – This is our tendency to complete an incomplete object.

- Good continuation – States that items which appear to continue a pattern will be seen as part of a pattern

- Pragnanz – Also called the law of good figure or simplicity, this is when we see an object as simple as possible.

These principles help us to make sense of a world full of raw sensations. Other ways we make sense of our world, though not covered here, include monocular and binocular cues which aid with depth perception, perceptual constancy, apparent motion, and optical illusions.

13.2. Attention: Motivated to Commit Cognitive Resources

Section Learning Objectives

- Define attention.

- Clarify what it means to be distracted.

- Clarify the role of the central executive.

- Define selective attention.

- Explain how the concepts of processing capacity and perceptual load explain how attention can be focused and not distracted.

- Describe inattentional blindness.

- Hypothesize whether attention can be divided.

Attention is our ability to focus on certain aspects of our environment at the exclusion of others. Despite this, we can be distracted, or when one stimulus interferes with our attending to another. In light of what you learned in Module 1, we have to wonder if distraction is really a form of being unmotivated or motivated to another end. Could it be that we allow ourselves to be distracted? Of course, yes, but there are also times when we are busily at work, and someone interrupts us. My wife seems to know when I am achieving an epiphany while writing a textbook or replying to students in my online courses and comes into my office and waits to be acknowledged. This is better than in the past when she just started to talk. Still, someone hovering over you will make you nervous and engage in motivated behavior to end that state of nervousness (i.e., the acknowledgement of her presence) at the expense of productivity.

So how do we choose to what to attend? Baddeley (1996) proposed that attention is controlled by what he called the central executive. It tells us where to focus our attention and can even home in on specific aspects of a stimulus such as the tone in a speaker’s voice, color in someone’s face, a noxious smell, or peculiar taste.

We can even use selective attention to voluntarily focus on specific sensory input from our environment (Freiwald & Kanwisher, 2004). As such, we might choose to focus on an aspect of a professor’s lecture when it is interesting but begin paying attention more to people walking by in the hallway if it becomes boring and dry. Of course, arousal theory (Module 1) suggests that when our arousal level is low, we could go to sleep or fall into a coma. I fortunately have never induced a coma in my students before. I cannot say there has not been snoring though.

How we can focus our attention and not be distracted by outside stimuli is a function of our processing capacity or how much information we can handle and perceptual load or how difficult a task is. Low-load tasks use up only a small amount of our processing capacity while high-load tasks use up much more. Lavie’s load theory of attention posits that we can attend to task-irrelevant stimuli since only some of our cognitive resources have been used when engaged in low-load tasks, but high load tasks do not leave us any resources to process other stimuli.

Before moving on, check the following out: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vJG698U2Mvo

******************************************************************************

Note: If you did not actually watch the short video, the next section will not make sense.

******************************************************************************

Did you count the number of passes correctly? Likely not and if this is true, it is due to the phenomena of inattentional blindness or when we miss a stimulus clearly present in our visual field when our attention is focused on a task (Simon & Chabris, 1999). In the video, you were presented with 2, three-person basketball teams who were passing the ball to other members of their team. One team wore white shirts and the other black. The participant had to count the number of times members of one of the two teams passed the ball to other team members, all while ignoring the other team. During this, a person wearing a gorilla suit walks through the basketball game, stopping to turn in the direction of the camera and thump its chest. Only half of the participants see the gorilla walk through. Did you?

Visit the Invisible Gorilla website to learn more about this study: http://theinvisiblegorilla.com/

Two types of blindness are worth mentioning too, and not in relation to problems in the visual sensory system. First, repetition blindness is when we experience a reduction in the ability to perceive repeated stimuli if flashed rapidly before our eyes. Say for example a series of numbers are flashed in rapid succession and during this string the number 3 is flashed four times in a row. You may recall only seeing 3 one time, not four. Is it because we cannot visually separate the numbers? No. If the same experiment was repeated with letters, and in the midst of a string of letters you saw R r, you would believe only one R/r was presented to you.

Second, change blindness occurs when two pictures are flashed before our eyes in rapid succession. If the second picture differs slightly from the first, you will not see the difference as well as you could if presented side-by-side. The effect is stronger when the change is not in the central portion of the picture but in a peripheral area.

Finally, can we successfully divide our attention or focus on more than one stimulus at a time? Results of several experiments show that it is possible to successfully divide our attention for tasks that we have practiced numerous times but as the task becomes more difficult this ability quickly declines (Schneider & Shiffrin, 1977). Of course, dividing our attention comes with risks, especially where driving and texting are concerned. Finley, Benjamin, & McCarley (2014) found that people can anticipate the costs of multitasking, but do not believe they are personally vulnerable to the risks compared to other people.

What does the literature say on driving and cell phone use? I am not going to dedicate pages of text saying what you have likely already heard on the news. Instead, APA wrote a great article on this issue that I will direct you to instead:

https://www.apa.org/research/action/drive.aspx.

Please check out the article before moving on.

13.3. Memory: Motivated to Retain and Retrieve Information

Section Learning Objectives

- Define memory.

- Describe the three stages of memory.

- Outline the seven sins of memory.

- Clarify how amnesia and interference lead to forgetting.

13.3.1. What is Memory?

In this class you have likely already taken a few exams. As you completed each, you had to draw the information it asked about from your storehouse of information that we typically refer to as memory, whether you were trying to recall dates, names, ideas, or a procedure. Simply, memory is the cognitive process we use to retain and retrieve information for later use. Two subprocesses are listed in this definition – retain and retrieve. The former is when we encode, consolidate, and store information. The latter is when we extract this information and use it in some way.

You might think of memory as a file cabinet. If you have one at home you use it to store information, or pieces of paper, away for use later. Hopefully your system of filing this information is good and you can easily find a document when you need it again. Our memory operates in the same general way. We take pieces of information and place them in this file cabinet. We should know what drawer, where in that drawer in terms of a specific hanging folder, and then were in the folder our information is. If we do, we find the information and use it when we need it again, such as during an exam. As you will soon come to see, the cabinet represents long-term memory (LTM) and when we pull information from it, we move it into a special type of short-term memory (STM) called working memory.

13.3.2. Stages of Memory

Atkinson and Shiffrin (1968) proposed a three-stage model of memory which said that memory proceeds from sensory, to short-term, and finally to long-term memory. First, sensory memory holds all incoming sensory information detected from our environment for a very short period of time (i.e., a few seconds or even a fraction of a second). Second, short-term memory holds a limited amount of information for a slightly longer period (about 15 to 20 seconds). Third, long-term memory holds a great deal of information for an indefinite period, possibly for decades (consider that the elderly can recall events from childhood if properly motivated). Let’s tackle each briefly.

13.3.2.1. Sensory memory. Information obtained from our five sensory organs moves to sensory memory, also called the sensory register. This memory system has a near unlimited capacity but information fades from it very quickly. For instance, visual stimuli are stored in what is called the iconic register but only lasts here for a fraction of a second (Sperling, 1960) while auditory information is stored in the echoic register for a few seconds (Darwin et al., 1972).

13.3.2.2. Short-term memory (STM). Our second memory system holds information for about 15-20 seconds (Peterson & Peterson, 1959; Brown, 1958) meaning that what you just read in the sensory memory section is still in your STM. Likely what you read in Section 13.1 is no longer present. Also, the capacity of STM has been found to be 5 to 9 items (Miller, 1956) with the average being 7. Miller (1956) also proposed that we can take larger lists of unrelated and meaningless material and group them into smaller, meaningful units in a process called chunking. For example, if you were given a list of states to include: Rhode Island, Pennsylvania, Washington, Maine, Oregon, California, Maryland, South Dakota, Florida, Nebraska, and Arizona, you could group them as follows:

- Rhode Island, Maine, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Florida falling on the east coast

- Washington, Oregon, California, and Arizona falling toward the west coast

- South Dakota and Nebraska falling in the middle of the country

Alone, the list of 11 items exceeds our capacity for STM but making three smaller lists falls on the short side of the capacity and no list itself has more than five items, still within the limits.

Our STM also holds information retrieved from long term memory to be used temporarily, sort of like taking the information from the file cabinet and placing it on a table. We call this working memory (Baddeley & Hitch, 1974). Once finished with the information, it is returned to the file cabinet for future use. It is important to point out the word use in the definition. By use it is implied that the information is manipulated in some way and makes it distinct from STM which just involves a mechanism of temporary storage.

13.3.2.3. Long-term memory (LTM). As the name indicates, information stored in this memory system is retained for a long period with the ability to be retrieved when needed. There seems to be no time limit for LTM and when people use the word memory, it is LTM they are referring to. There are two specific types of LTM – implicit and explicit. First, implicit memory includes knowledge based on prior experience and is called nondeclarative. An example is a procedural memory or memory of how to complete a task such as make a grilled cheese sandwich, ride a bike, or ring up a customer on a cash register. Second, explicit memory includes the knowledge of facts and events. This type is said to be declarative as it can be deliberately accessed. It includes semantic memory or memory of facts such as what the definition of semantic memory is and episodic memory or the memory of a personally experienced event. Again, in the case of either semantic or episodic memory you must declare it. The knowledge is not automatic.

The serial position effect states that we recall information falling at the beginning (called primary) and end (called recency) of a list better than the information in the middle. Think about the most recent lecture you attended. What do you remember best? Likely, you remember what the professor said when class started such as if he/she made a few quick announcements or did a review of previously covered material and at the end in terms of final comments or a summary of new material. We remember the information presented first likely since it has had time to make its way into LTM because we could rehearse it (Rundus, 1971). As for the end of a list, we likely recall it because it is still in STM and accessible to us (Glanzer & Cunitz, 1966).

LTM includes four main steps – encoding, consolidation, storage, and retrieval. First, encoding is when we pay attention to and take in information that can then be processed or moved to LTM. This processing is either automatic or done with little effort such as remembering what we had for lunch today or is effortful and requires us to commit cognitive resources such as remembering the vocabulary (bolded terms) in this module.

According to the levels of processing theory (Craik & Lockhart, 1972), our memory is dependent on the depth of processing that information receives. It can be shallow or not involving any real attention to meaning such as saying the phone number of a person you just met at a party repeatedly or is deep, indicating you pay close attention to the information and apply some type of meaning to it.

The next step in the process is consolidation or when we stabilize and solidify a memory (Muller & Pilzecker, 1900). Sleep is important for consolidation and is the reason why studying all night before a test the next day really does not help much (Gais, Lucas, & Born, 2006). The third step is storage and involves creating a permanent record of the information. This record must be logically created so that we can find the information later in the final part of the process called retrieval.

13.3.3. Memory Errors and Forgetting

In his book, “The Seven Sins of Memory: How the Mind Forgets and Remembers,” Schacter (2002) outlines seven major categories of memory errors broken down into three sins of omission or forgetting and four sins of commission or distortions in our memories.

The sins of omission include:

- Transience or when our memories decrease in accessibility over time

- Absent-mindedness or when we forget to do things or have a lapse of attention such as not remembering where we put our keys

- Blocking or when we experience the tip-of-the-tongue phenomena and just cannot remember something. The stored information is temporarily inaccessible.

The sins of commission include:

- Suggestibility or when false memories are created due to deception or leading questions.

- Bias or when current knowledge, beliefs, and feelings skew our memory of past events such as only remembering the bad times and not the good ones after a relationship has come to a tragic end.

- Persistence or when unwanted memories continue and are not forgotten such as in the case of PTSD.

- Misattribution or when we believe a memory comes from one source when it really came from another source.

For more on these sins, please visit: https://www.apa.org/monitor/oct03/sins.aspx

Forgetting can also occur due to amnesia or a condition in which an individual is unable to remember what happened either shortly before (retrograde) or after (anterograde) a head injury. Forgetting can also be due to interference or when information that is similar to other information interferes in either storage or retrieval. Interference can be proactive as when old information interferes with new or retroactive in which new information interferes with old. Proactive interference explains why students have trouble understanding the concepts of positive and negative correlations and positive and negative reinforcement/punishment. Our previous education taught us that positive implies something good and negative something bad. Our new learning shows that positive can mean moving in the same direction and negative means moving in opposite directions as correlations show, or that positive means giving and negative means taking away in respects to reinforcement and punishment. Again, our previous learning interferes with new learning. When you take an abnormal psychology class you will see a third use of positive and negative in relation to the symptoms of schizophrenia. No symptom of this disease is good so the words positive and negative have no affective connotation yet again, but this pervious learning will make our new understanding a bit more challenging to gain.

All students struggle with test taking from time to time and this usually centers on how they go about studying for exams. Below are some websites with useful tips for studying, and some of the strategies have been mentioned already in Section 13.3. Enjoy.

13.4. Problem Solving: Motivated to Find Solutions

Section Learning Objectives

- Define problems.

- Describe insight learning.

- Define and exemplify functional fixedness.

Let’s face it. Hardly anything in life runs smoothly. Even with the best laid plan and clearest goals we can formulate, success can be elusive. We might even be unsure how to proceed or to solve what are called problems or when we cannot achieve a goal due to an obstacle that we are unsure how to overcome. In Section 13.1 we discussed Gestalt principles of perceptual organization but in this section, we focus on what they said about problem solving. Simply, when it comes to problem solving, the Gestalt psychologists said that we had to proceed from the whole problem down to its parts. How so? Kohler studied the problem-solving abilities of chimpanzees and used simple props such as the bars of the cages, bananas, sticks, and a box. Chimps were placed in a cage with bananas hanging over head. They could use any prop they needed to get them, but no one prop alone would suffice. The chimps had to figure out what combination of props would aid them in getting the bananas. At first, they did not do well but then out of nowhere saw the solution to the problem. He called this insight learning or the spontaneous understanding of relationships. The chimps had to look at the whole situation and the relationships among stimuli, or to restructure their perceptual field, before the solution to the problem could be seen.

One obstacle to problem solving is what is called functional fixedness or when we focus on a typical use or familiar function of an object. Duncker (1945) demonstrated this phenomenon using what he called the candle problem. Essentially, participants were given candles, tacks, and matches in a matchbox and were asked to mount a candle on a vertical corkboard attached to the wall such that it would not drip wax on the floor. To successfully complete the task, the participant must realize that the matchbox can be used as a support and not just a container. In his study, Duncker presented one group with small cardboard boxes containing the materials and another group with all the same materials but not in the boxes (they were sitting beside the boxes). The group for which the materials were in the boxes found the task more difficult than the group for which the materials were outside. In the case of the latter, these participants were able to see the box as not just a container but as another tool to use to solve the problem.

As you can see from the candle problem, and other related problem-solving tasks, we sometimes need to think outside of the box or to demonstrate creativity. This is called divergent thinking or thinking that involves more than one possible solution and that is open-ended. Part of the open-endedness is coming up with ideas on how to solve the problem, which we call brainstorming. Really, any idea could have merit so just saying whatever comes to mind is important.

13.5. Reasoning: Motivated to Make Good Decisions

Section Learning Objectives

- Differentiate deductive from inductive reasoning.

- Define heuristics and describe types.

- Outline errors we make when reasoning.

13.5.1. Types of Reasoning

Though you are sitting in a college classroom now, how did you get there? Did you have to choose between two or more universities? Did you have to debate which area to major in? Did you have to decide which classes to take this semester to fit your schedule? Or, what I bet many students thought I was asking about, did you have to decide whether you were walking, riding a bike, or taking the bus to school? No matter which question, you engaged in reasoning centered on making a good decision or judgement. There are two types of reasoning we will briefly discuss – formal or deductive and informal or inductive.

First, we use formal or deductive reasoning when the procedure needed to draw a conclusion is clear and only one answer is possible. This approach makes use of algorithms or a logical sequence of steps that always produces a correct solution to the problem. For instance, solve the following problem:

3x + 20 = 41

- Step 1 – Subtract 20 from both sides resulting in: 3x = 21

- Step 2 – Divide each side by 3 resulting in x = 7

- Check your answer by substituting 7 for x in the original problem resulting in 21+20=41 which is correct.

Deductive reasoning also uses the syllogism which is a logical argument consisting of premises and a conclusion. For example:

- Premise 1 – All people die eventually.

- Premise 2 – I am a person.

- Conclusion – Therefore, I will die eventually.

Second, informal or inductive reasoning is used when there is no single correct solution to a problem. A conclusion may or may not follow from premises or facts. Consider the following:

- Observation – It has snowed in my town the past five years during winter.

- Conclusion – It will snow this winter.

Though it has snowed the past five years it may not necessarily this year. The conclusion does not necessarily follow from the observation. What might affect the strength of an inductive argument then? First, the number of observations is important. In our example, we are basing our conclusion on just five years of data. If the first statement said that it snowed the past 50 years during winter, then our conclusion would be much stronger. Second, we need to consider how representative our observations are. Since they are only about our town and our conclusion only concerns it, the observations are representative. Finally, we need to examine the quality of the evidence. We could include meteorological data from those five years showing exactly how much snow we obtained. If by saying it snowed, we are talking only about a trace amount each year, though technically it did snow, this is not as strong as saying we had over a foot of snow during each year of the observation period.

13.5.2. Heuristics and Cognitive Errors

As noted in Module 1, the past can be used to motivate behavior and the same is true in terms of decision making. We use our past experiences as a guide or shortcut to make decisions quickly. These mental shortcuts are called heuristics. Though they work well, they are not fool proof. First, the availability heuristic is used when we make estimates about how often an event occurs based on how easily we can remember examples (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974). The easier we can remember examples, the more often we think the event occurs. This sounds like a correlation between events and is. The problem is that the correlation may not actually exist, called an illusory correlation.

Another commonly used heuristic is the representative heuristic or believing something comes from a larger category based on how well it represents the properties of the category. It can lead to the base rate fallacy or when we overestimate the chances that some thing or event has a rare property, or we underestimate that something has a common property.

A third heuristic is the affect heuristic or thinking with our heart and not our head. As such, we are driven by emotion and not reason. Fear appeals are an example. Being reminded that we can die from lung cancer if we smoke may fill us with dread.

In terms of errors in reasoning, we sometimes tend to look back over past events and claim that we knew it all along. This is called the hindsight bias and is exemplified by knowing that a relationship would not last after a breakup. Confirmation bias occurs when we seek information and arrive at conclusions that confirm our existing beliefs. If we are in love with someone, we will only see their good qualities but after a breakup, we only see their negative qualities. Finally, mental set is when we attempt to solve a problem using what worked well in the past. Of course, what worked well then may not now and so we could miss out on a solution to the problem. Functional fixedness, discussed in Section 13.4, is an example of this. Recall from Module 6 that when conducting a functional assessment, we figure out the antecedents leading to, and the consequences maintaining, a problem behavior. But we also figure out if there have been previous interventions that worked or did not work. Though a specific strategy worked in the past does not mean it will in the future and one that did not work then may work now. This represents mental set, especially within self-modification.

13.6. Motivated to Learn…and at Times, Unlearn/Relearn

Section Learning Objectives

- Define learning.

- Outline the two main forms of learning and types occurring under each.

- Clarify what nonassociative learning is and its two forms.

- Clarify the importance of Pavlov’s work.

- Describe how respondent behaviors work.

- Describe Pavlov’s classic experiment, defining any key terms.

- Explain how fears are both learned and unlearned in respondent conditioning.

- Define operant conditioning.

- Contrast reinforcement and punishment.

- Clarify what positive and negative mean.

- Outline the four contingencies of behavior.

- Distinguish primary and secondary reinforcers.

- List and describe the five factors on the effectiveness of reinforcers.

- Contrast continuous and partial/intermittent reinforcement.

- List the four main reinforcement schedules and exemplify each.

- Define extinction.

- Clarify which type of reinforcement extinguishes quicker.

- Define extinction burst.

- Define spontaneous recovery.

- Differentiate observational and enactive learning.

- Describe Bandura’s classic experiment.

- Clarify how observational learning can be used in behavior modification

13.6.1. Defining Terms

Our attention now turns to the cognitive process called learning. You have already used this cognitive ability numerous times in the course as you learned the content from Modules 1-12. This process is no different in Module 13, the final two modules, or what you are doing for other classes. So, what is learning? Learning is any relatively permanent change in behavior due to experience and practice. The key part of this definition is the word relatively. Nothing is set in stone and what is learned can be unlearned. Consider a fear for instance. Maybe a young baby enjoys playing with a rat, but each time the rat is present a loud sound occurs. The sound is frightening for the child and after several instances of the sound and rat being paired, the child comes to expect a loud sound at the sight of the rat, and cries. What has occurred is that an association has been realized, stored in long term memory, and retrieved to working memory when a rat is in view. The memory of the loud sound has been retained and retrieved in the future when the rat is present. But memories change. With time, and new learning, the child can come to see rats in a positive light and replace the existing scary memory with a pleasant one. This will affect future interactions with white rats.

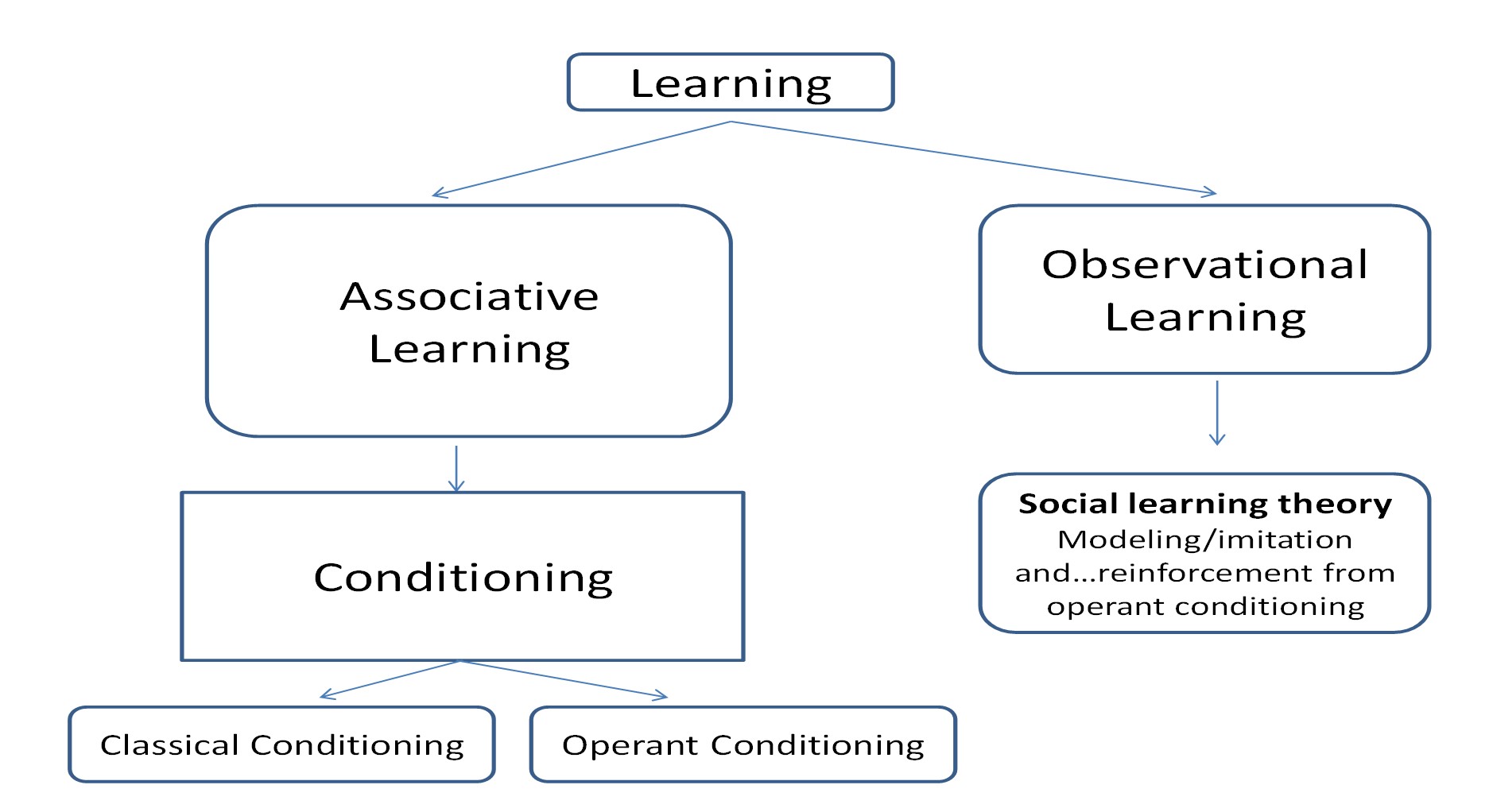

Take a look at Figure 13.1 below. Notice that learning occurs in two main ways – associative learning and observational learning. Associative learning is when we link together two pieces of information sensed from our environment. Conditioning, as a type of associative learning, is when two events are linked. This leads to two types of conditioning – classical/respondent/Pavlovian or the linking together of two types of stimuli and operant or the linking of response and consequence. On the other side is observational learning or learning by observing the world around us. Though under it is social learning theory, please note that this form of learning combines observational learning and operant conditioning. More on all of these later.

Figure 13.1. Types of Learning

To be complete, there is a third type of learning called nonassociative learning. In this type of learning there is no linking of information or observing the actions of those around you. It can occur in two forms. First, habituation occurs when we simply stop responding to repetitive and harmless stimuli in our environment such as a fan running in your laptop as you work on a paper. If there is a slight change in the stimulus, however, we shift our attention back to it, which is called the orienting response. Second is what is called sensitization or what occurs when our reactions are increased due to a strong stimulus, such as an individual who experienced a mugging. Both types of nonassociative learning could be regarded as very basic examples of learning—the learning for which we are prewired.

13.6.2. Respondent Conditioning

You have likely heard about Pavlov and his dogs but what you may not know is that this was a discovery made accidentally. Ivan Petrovich Pavlov (1906, 1927, 1928), a Russian physiologist, was interested in studying digestive processes in dogs in response to being fed meat powder. What he discovered was the dogs would salivate even before the meat powder was presented. They would salivate at the sound of a bell, footsteps in the hall, a tuning fork, or the presence of a lab assistant. Pavlov realized there were some stimuli that automatically elicited responses (such as salivating to meat powder) and those that had to be paired with these automatic associations for the animal or person to respond to it (such as salivating to a bell). Armed with this stunning revelation, Pavlov spent the rest of his career investigating the learning phenomenon.

The important thing to understand is that not all behaviors occur due to reinforcement and punishment as operant conditioning says. In the case of respondent conditioning, antecedent stimuli exert complete and automatic control over some behaviors. We see this in the case of reflexes. When a doctor strikes your knee with that little hammer it extends out automatically. You do not have to do anything but watch. Babies will root for a food source if the mother’s breast is placed near their mouth. If a nipple is placed in their mouth, they will also automatically suck, as per the sucking reflex. Humans have several of these reflexes though not as many as other animals due to our more complicated nervous system.

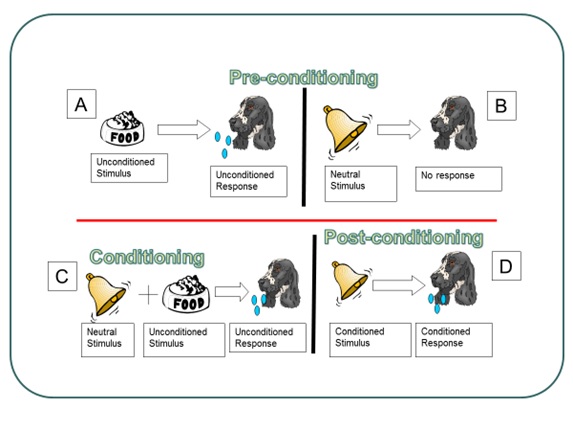

Respondent conditioning occurs when we link a previously neutral stimulus with a stimulus that is unlearned or inborn, called an unconditioned stimulus. In respondent conditioning, learning occurs in three phases: preconditioning, conditioning, and postconditioning. See Figure 13.2 for an overview of Pavlov’s classic experiment.

13.6.2.1. Preconditioning. Notice that preconditioning has both an A and a B panel. Really, all this stage of learning signifies is that some learning is already present. There is no need to learn it again. In Panel A, food makes a dog salivate. This does not need to be learned and is the relationship of an unconditioned stimulus (UCS) yielding an unconditioned response (UCR). Unconditioned means unlearned. In Panel B, we see that a neutral stimulus (NS) yields nothing. Dogs do not enter the world knowing to respond to the ringing of a bell (which it hears).

13.6.2.2. Conditioning. Conditioning is when learning occurs. Through a pairing of neutral stimulus and unconditioned stimulus (bell and food, respectively) the dog will learn that the bell ringing (NS) signals food coming (UCS) and salivate (UCR). The pairing must occur more than once so that needless pairings are not learned such as someone farting right before your food comes out and now you salivate whenever someone farts (…at least for a while. Eventually the fact that no food comes will extinguish this reaction but still, it will be weird for a bit).

13.6.2.3. Postconditioning. Postconditioning, or after learning has occurred, establishes a new and not naturally occurring relationship of a conditioned stimulus (CS; previously the NS) and conditioned response (CR; the same response). So, the dog now reliably salivates at the sound of the bell because he expects that food will follow, and it does.

Figure 13.2. Pavlov’s Classic Experiment

13.6.3. Operant Conditioning

Operant conditioning is a type of associate learning which focuses on consequences that follow a response or behavior that we make (anything we do, say, or think/feel) and whether it makes a behavior more or less likely to occur.

13.6.3.1. Contingencies of reinforcement. The basis of operant conditioning is that you make a response for which there is a consequence. Based on the consequence you are more or less likely to make the response again. This section introduces the term contingency. A contingency is when one thing occurs due to another. Think of it as an If-Then statement. If I do X, then Y will happen. For operant conditioning this means that if I make a behavior, then a specific consequence will follow. The events (response and consequence) are linked in time.

What form do these consequences take? There are two main ways they can present themselves.

-

- Reinforcement – Due to the consequences, a behavior/response is more likely to occur in the future. It is strengthened.

- Punishment – Due to the consequence, a behavior/response is less likely to occur in the future. It is weakened.

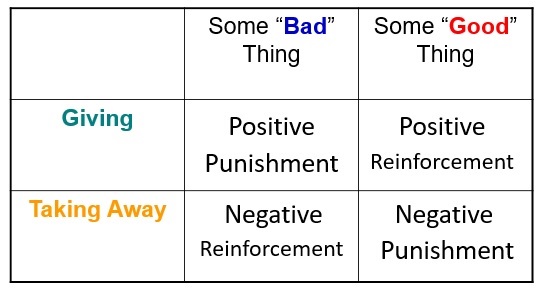

Reinforcement and punishment can occur as two types – positive and negative. Again, these words have no affective connotation to them meaning they do not imply good or bad. Positive means that you are giving something – good or bad. Negative means that something is being taken away – good or bad. Check out Figure 13.3 for how these contingencies are arranged.

Figure 13.3. Contingencies in Operant Conditioning

Let’s go through each:

- Positive Punishment (PP) – If something bad or aversive is given or added, then the behavior is less likely to occur in the future. If you talk back to your mother and she slaps your mouth, this is a PP. Your response of talking back led to the consequence of the aversive slap being delivered or given to your face.

- Positive Reinforcement (PR) – If something good is given or added, then the behavior is more likely to occur in the future. If you study hard and earn, or are given, an ‘A’ on your exam, you will be more likely to study hard in the future.

- Negative Punishment (NP) – This is when something good is taken away or subtracted making a behavior less likely in the future. If you are late to class and your professor deducts 5 points from your final grade (the points are something good and the loss is negative), you will hopefully be on time in all subsequent classes.

- Negative Reinforcement (NR) – This is a tough one for students to comprehend because the terms don’t seem to go together and are counterintuitive. But it is really simple, and you experience NR all the time. This is when something bad or aversive is taken away or subtracted due to your actions, making it that you will be more likely to make the same behavior in the future when some stimuli is present. For instance, what do you do if you have a headache? You likely answered take Tylenol. If you do this and the headache goes away, you will take Tylenol in the future when you have a headache. NR can either result in current escape behavior or future avoidance behavior. What does this mean? Escape occurs when we are presently experiencing an aversive event and want it to end. We make a behavior and if the aversive event, like the headache, goes away, we will repeat the taking of Tylenol in the future. This future action is an avoidance event. We might start to feel a headache coming on and run to take Tylenol right away. By doing so we have removed the possibility of the aversive event occurring and this behavior demonstrates that learning has occurred.

13.6.3.2. Primary vs. secondary (conditioned). The type of reinforcer or punisher we use is important. Some are naturally occurring while some need to be learned. We describe these as primary and secondary reinforcers and punishers. Primary refers to reinforcers and punishers that have their effect without having to be learned. Food, water, temperature, and sex, for instance, are primary reinforcers while extreme cold or hot or a punch on the arm are inherently punishing. A story will illustrate the latter. When I was about 8 years old, I would walk up the street in my neighborhood saying, “I’m Chicken Little and you can’t hurt me.” Most ignored me but some gave me the attention I was seeking, a positive reinforcer. So, I kept doing it and doing it until one day, another kid was tired of hearing about my other identity and punched me in the face. The pain was enough that I never walked up and down the street echoing my identity crisis for all to hear. This was a positive punisher and did not have to be learned. That was definitely not one of my finer moments in life.

Secondary or conditioned reinforcers and punishers are not inherently reinforcing or punishing but must be learned. An example was the attention I received for saying I was Chicken Little. Over time I learned that attention was good. Other examples of secondary reinforcers include praise, a smile, getting money for working or earning good grades, stickers on a board, points, getting to go out dancing, and getting out of an exam if you are doing well in a class. Examples of secondary punishers include a ticket for speeding, losing television or video game privileges, being ridiculed, or a fee for paying your rent or credit card bill late. Really, the sky is the limit with reinforcers.

13.6.3.3. Factors affecting the effectiveness of reinforcers and punishers. The four contingencies of behavior can be made to be more or less effective by taking a few key steps. These include:

- It should not be surprising to know that the quicker you deliver a reinforcer or punisher after a response, the more effective it will be. This is called immediacy. Don’t be confused by the word. If you notice, you can see immediately in it. If a person is speeding and you ticket them right away, they will stop speeding. If your daughter does well on her spelling quiz, and you take her out for ice cream after school, she will want to do better.

- The reinforcer or punisher should be unique to the situation. So, if you do well on your report card, and your parents give you $25 for each A, and you only get money for school performance, the secondary reinforcer of money will have an even greater effect. This ties back to our discussion of contingency.

- But also, you are more likely to work harder for $25 an A than you are $5 an A. This is called magnitude. Premeditated homicide or murder is another example. If the penalty is life in prison and possibly the death penalty, this will have a greater effect on deterring the heinous crime than just giving 10 years in prison with the chance of parole.

- At times, events make a reinforcer or punisher more or less reinforcing or punishing. We call these motivating operations and they can take the form of an establishing or an abolishing operation. If we go to the store when hungry or in a state of deprivation, food becomes even more reinforcing and we are more likely to pick up junk food. This is an establishing operation and is when an event makes a reinforcer or punisher more potent and so more likely to occur. What if you went to the grocery store full or in a state of satiation? In this case, junk food would not sound appealing, and you would not buy it and throw your diet off. This is an abolishing operation and is when an event makes a reinforcer or punisher less potent and so less likely to occur. An example of a punisher is as follows: If a kid loves playing video games and you offer additional time on Call of Duty for completing chores both in a timely fashion and correctly, this will be an establishing operation and make Call of Duty even more reinforcing. But what if you offer a child video game time for doing those chores and he or she does not like playing them? This is now an abolishing operation, and the video games are not likely to induce the behavior you want.

- The example of the video games demonstrates establishing and abolishing operations, but it also shows one very important fact – all people are different. Reinforcers will motivate behavior. That is a universal occurrence and unquestionable. But the same reinforcers will not reinforce all people. This shows diversity and individual differences. Before implementing any type of behavior modification plan, whether on yourself or another person, you must make sure you have the right reinforcers and punishers in place.

Alright. Now that we have established what contingencies are, let’s move to a discussion of when we reinforce.

13.6.3.4. Schedules of reinforcement. In operant conditioning, the rule for determining when and how often we will reinforce a desired behavior is called the reinforcement schedule. Reinforcement can either occur continuously, meaning every time the desired behavior is made the person or animal will receive some reinforcer, or intermittently/partially, meaning reinforcement does not occur with every behavior. Our focus will be on partial/intermittent reinforcement.

Figure 13.4. Key Components of Reinforcement Schedules

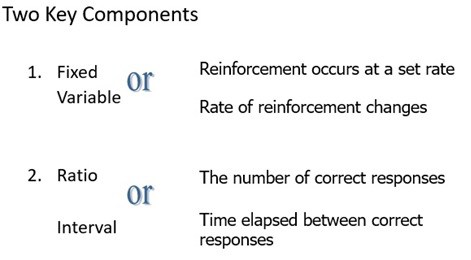

Figure 13.4. shows that there are two main components that make up a reinforcement schedule – when you will reinforce and what is being reinforced. In the case of when, it will be either fixed or at a set rate, or variable and at a rate that changes. In terms of what is being reinforced, we will either reinforce responses or time. These two components pair up as follows:

- Fixed Ratio schedule (FR) – With this schedule, we reinforce some set number of responses. For instance, every twenty problems (fixed) a student gets correct (ratio), the teacher gives him an extra credit point. A specific behavior is being reinforced – getting problems correct. Note that if we reinforce each occurrence of the behavior, the definition of continuous reinforcement, we could also describe this as a FR1 schedule. The number indicates how many responses must be made and, in this case, it is one.

- Variable Ratio schedule (VR) – We might decide to reinforce some varying number of responses such as if the teacher gives him an extra credit point after finishing between 40 and 50 problems correctly. This is useful after the student is obviously learning the material and does not need regular reinforcement. Also, since the schedule changes, the student will keep responding in the absence of reinforcement.

- Fixed Interval schedule (FI) – With a FI schedule, you will reinforce after some set amount of time. Let’s say a company wanted to hire someone to sell their products. To attract someone, they could offer to pay them $10 an hour 40 hours a week and give this money every two weeks. Crazy idea but it could work. Saying the person will be paid every indicates fixed, and two weeks is time or interval. So, FI. How might knowing the timing of your paychecks be motivating?

- Variable Interval schedule (VI) – Finally, you could reinforce someone at some changing amount of time. Maybe they receive payment on Friday one week, then three weeks later on Monday, then two days later on Wednesday, then eight days later on Thursday, etc. This could work, right? Not likely within the context of being paid for a job, but what about in terms of incentives received for working hard? An employer could decide to give small bonuses to its employees at some varying amount of time. You might receive the bonus today and then again in three months and then in 2 weeks after that. The schedule of when to reinforce, or provide the bonus, varies and so employees will work hard not knowing when the next reinforcer will come. Again, how is this motivating?

13.6.3.5. Extinction and spontaneous recovery. We now discuss two properties of operant conditioning – extinction and spontaneous recovery. First, extinction is when something that we do, say, think/feel has not been reinforced for some time. As you might expect, the behavior will begin to weaken and eventually stop when this occurs. Does extinction just occur as soon as the anticipated reinforcer is not there? The answer is yes and no, depending on whether we are talking about continuous or partial reinforcement. With which type of reinforcement would you expect a person to stop responding to immediately if reinforcement is not there?

Do you suppose continuous? Or partial?

The answer is continuous. If a person is used to receiving reinforcement every time the correct behavior is made and then suddenly no reinforcer is delivered, he or she will cease the response immediately. Obviously then, with partial, a response continues being made for a while. Why is this? The person may think the schedule has simply changed. ‘Maybe I am not paid weekly now. Maybe it changed to biweekly, and I missed the email.’ Due to this we say that intermittent or partial reinforcement shows resistance to extinction, meaning the behavior does weaken, but gradually.

As you might expect, if reinforcement “mistakenly” occurs after extinction has started, the behavior will re-emerge. Consider your parents for a minute. To stop some undesirable behavior you made in the past surely they took away a privilege. I bet the bad behavior ended too. But did you ever go to your grandparent’s house and grandma or grandpa, or worse, BOTH….. took pity on you and let you play your video games for an hour or two (or something equivalent)? I know my grandmother used to. What happened to that bad behavior that had disappeared? Did it start again, and your parents could not figure out why? Don’t worry. Someday your parents will get you back and do the same thing with your kid(s).

When extinction first occurs, the person or animal is not sure what is going on and actually begins to make the response more often (frequency), longer (duration), and stronger (intensity). This is called an extinction burst. We might even see novel behaviors such as aggression. I mean, who likes having their privileges taken away? That will likely create frustration which can lead to aggression.

One final point about extinction is important. You must know what the reinforcer is and be able to eliminate it. Say your child bullies other kids at school. Since you cannot be there to stop the behavior, and most likely the teacher cannot be either if it is done on the playground at recess, the behavior will continue. Your child will continue bullying because it makes him or her feel better about themselves (a PR).

With all this in mind, you must have wondered if extinction is the same as punishment. With both, you are stopping an undesirable behavior, correct? Yes, but that is the only similarity they share. Punishment reduces unwanted behavior by either giving something bad or taking away something good. Extinction is simply when you take away the reinforcer for the behavior. This could be seen as taking away something good, but the good in punishment is not usually what is reinforcing the bad behavior. If a child misbehaves (the bad behavior) for attention (the PR), then with extinction you would not give the PR (meaning nothing happens) while with punishment, you might slap his or her behind (a PP) or taking away tv time (an NP).

You might have wondered if the person or animal will try to make the response again in the future even though it stopped being reinforced in the past. The answer is yes and is called spontaneous recovery. One of two outcomes is possible. First, the response is made and nothing happens. In this case extinction continues. Second, the response is made, and a reinforcer is delivered. The response re-emerges. Consider a rat that has been trained to push a lever to receive a food pellet. If we stop delivering the food pellets, in time, the rat will stop pushing the lever. The rat will push the lever again sometime in the future and if food is delivered, the behavior spontaneously recovers.

13.6.4. Observational Learning

13.6.4.1. Learning by watching others. There are times when we learn by simply watching others. This is called observational learning and is contrasted with enactive learning, which is learning by doing. There is no firsthand experience by the learner in observational learning unlike enactive. As you can learn desirable behaviors such as watching how your father bags groceries at the grocery store (I did this and still bag the same way today) you can learn undesirable ones too. If your parents resort to alcohol consumption to deal with the stressors life presents, then you too might do the same. What is critical is what happens to the model in all these cases. If my father seems genuinely happy and pleased with himself after bagging groceries his way, then I will be more likely to adopt this behavior. If my mother or father consumes alcohol to feel better when things are tough, and it works, then I might do the same. On the other hand, if we see a sibling constantly getting in trouble with the law then we may not model this behavior due to the negative consequences.

13.6.4.2. Bandura’s classic experiment. Albert Bandura conducted the pivotal research on observational learning, and you likely already know all about it (Bandura, Ross, & Ross, 1961; Bandura, 1965). In Bandura’s experiment, children were first brought into a room to watch a video of an adult playing nicely or aggressively with a Bobo doll. This was a model. Next, the children are placed in a room with a lot of toys in it. In the room is a highly prized toy but they are told they cannot play with it. All other toys are fine, and a Bobo doll is in the room. Children who watched the aggressive model, behaved aggressively with the Bobo doll while those who saw the nice model, played nice. Both groups were frustrated when deprived of the coveted toy.

13.6.4.3. Observational learning and behavior modification. Bandura said if all behaviors are learned by observing others and we model our behaviors on theirs, then undesirable behaviors can be altered or relearned in the same way. Modeling techniques are used to change behavior by having subjects observe a model in a situation that usually causes them some anxiety. By seeing the model interact nicely with the fear evoking stimulus, their fear should subside. This form of behavior therapy is widely used in clinical, business, and classroom situations. In the classroom, we might use modeling to demonstrate to a student how to do a math problem. In fact, in many college classrooms this is exactly what the instructor does. In the business setting, a model or trainer demonstrates how to use a computer program or run a register for a new employee.

Module Recap

That concludes our look at cognitive process and how they motivate behavior. As we have discussed so far in this course, behavior is controlled by internal processes and so when we engage in motivated behavior, it is due to commands sent out to the body from the nervous system and endocrine system. It does not matter if the action we make is self-initiated or in response to an environmental stimulus. Module 14 covers internal process similar to this module but in relation to physiological processes such as efforts to reduce drives and homeostasis. I hope you enjoyed the discussion. One final module before we round things out.

2nd edition