Learning Objectives

After reading this section, students should be able to …

- Explain the meaning of pricing from the perspective of the buyer, seller, and society

The McDonald’s effect

McDonald’s is one humongous company. With 21,000 restaurants in 101 countries, it is everywhere–which is why the global economy is sometimes called McWorld. Back home in America, the executives that run this vast empire are not feeling very lordly. More than ever they find they have to kowtow to the price demands of ordinary folks like Alonso Reyes, a 19-year-old from Chicago who works at a local car dealership. Never mind that Chicago is McDonald’s world headquarters—he splits his fast food patronage between McDonald’s and its arch-rival, Burger King, and counts every pennyworth of beef when deciding where to eat. So Reyes perked up when he heard that McDonald’s had announced “an unprecedented value offering”–a USD 0.55 Big Mac that the company boasted was bad news for their competition. “Cool,” said Reyes, “Coupons, specials, sales. I’ll take whatever I can get.”

For McDonald’s top management, this pricing strategy made perfect sense. After all, declining same-store sales in the US were the chain’s most glaring weakness. What better way to put some sizzle in the top line than a bold pocketbook appeal?

Well, McDonald’s executives should have realized that there is, in fact, a better way. Apparently they took no notice of the fallout when Phillip Morris announced deep cuts on “Marlboro Friday”, or of “Grape Nuts Monday”, when the Post unit of Kraft Foods kicked off a cereal price war. Predictably, “Hamburger Wednesday” sent investors on a Big Mac attack, slicing 9 per cent off McDonald’s share price in three days and dragging rival fast-food issues down with it. “It looks almost desperate,” says Piper Jaffray, Inc. analyst Allan Hickok of the USD 0.55 come-on. Adds Damon Brundage of NatWest Securities Corporation: “They have transformed one of the great brands in American business into a commodity.”

In theory, McDonald’s plan will payoff, because customers only get the discount if they buy a drink and frenchfries, too. Yet that gimmick-within-a-gimmick threatens to undermine pricier “Extra Value Meals”, one of the chain’s most successful marketing initiatives. Consumers expecting cut-rate combos will not go back to paying full price, especially if other fast-feeders discount their package deals. (32)

Introduction

From a customer’s point of view, value is the sole justification for price. Many times customers lack an understanding of the cost of materials and other costs that go into the making of a product. But those customers can understand what that product does for them in the way of providing value. It is on this basis that customers make decisions about the purchase of a product.

Effective pricing meets the needs of consumers and facilitates the exchange process. It requires that marketers understand that not all buyers want to pay the same price for products, just as they do not all want the same product, the same distribution outlets, or the same promotional messages. Therefore, in order to effectively price products, markets must distinguish among various market segments. The key to effective pricing is the same as the key to effective product, distribution, and promotion strategies. Marketers must understand buyers and price their products according to buyer needs if exchanges are to occur. However, one cannot overlook the fact that the price must be sufficient to support the plans of the organization, including satisfying stockholders. Price charged remains the primary source of revenue for most businesses.

Price defined: three different perspectives

Although making the pricing decision is usually a marketing decision, making it correctly requires an understanding of both the customer and society’s view of price as well. In some respects, price setting is the most important decision made by a business. A price set too low may result in a deficiency in revenues and the demise of the business. A price set too high may result in poor response from customers and, unsurprisingly, the demise of the business. The consequences of a poor pricing decision, therefore, can be dire. We begin our discussion of pricing by considering the perspective of the customer.

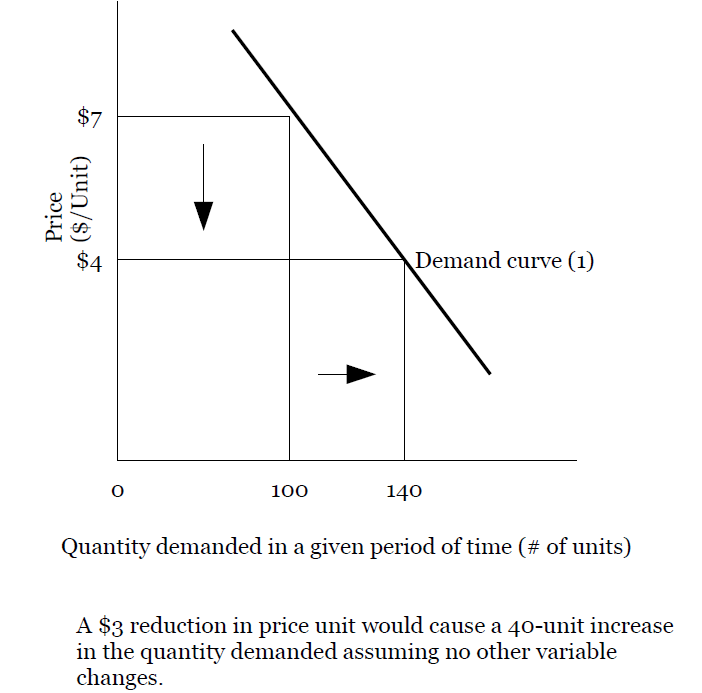

Figure 9.1: The customer’s view of price

The customer’s view of price

As discussed in an earlier chapter, a customer can be either the ultimate user of the finished product or a business that purchases components of the finished product. It is the customer that seeks to satisfy a need or set of needs through the purchase of a particular product or set of products. Consequently, the customer uses several criteria to determine how much they are willing to expend in order to satisfy these needs. Ideally, the customer would like to pay as little as possible to satisfy these needs. This perspective is summarized in Figure 9.1.

Therefore, for the business to increase value (i.e. create the competitive advantage), it can either increase the perceived benefits or reduce the perceived costs. Both of these elements should be considered elements of price. To a certain extent, perceived benefits are the mirror image of perceived costs. For example, paying a premium price (e.g. USD 650 for a piece of Lalique crystal) is compensated for by having this exquisite work of art displayed in one’s home. Other possible perceived benefits directly related to the price-value equation are status, convenience, the deal, brand, quality, choice, and so forth. Many of these benefits tend to overlap. For instance, a Mercedes Benz E750 is a very high-status brand name and possesses superb quality. This makes it worth the USD 100,000 price tag. Further, if one can negotiate a deal reducing the price by USD 15,000, that would be his incentive to purchase. Likewise, someone living in an isolated mountain community is willing to pay substantially more for groceries at a local store rather than drive 78 miles (25.53 kilometers) to the nearest Safeway. That person is also willing to sacrifice choice for greater convenience. Increasing these perceived benefits is represented by a recently coined term, value-added. Thus, providing value-added elements to the product has become a popular strategic alternative. Computer manufacturers now compete on value-added components such as free delivery setup, training, a 24-hour help line, trade-in, and upgrades.

Perceived costs include the actual dollar amount printed on the product, plus a host of additional factors. As noted, these perceived costs are the mirror-opposite of the benefits. When finding a gas station that is selling its highest grade for USD 0.06 less per gallon, the customer must consider the 16 mile (25.75 kilometer) drive to get there, the long line, the fact that the middle grade is not available, and heavy traffic. Therefore, inconvenience, limited choice, and poor service are possible perceived costs. Other common perceived costs include risk of making a mistake, related costs, lost opportunity, and unexpected consequences, to name but a few. A new cruise traveler discovers he or she really does not enjoy that venue for several reasons–e.g. he or she is given a bill for incidentals when she leaves the ship, has used up her vacation time and money, and receives unwanted materials from this company for years to come.

In the end, viewing price from the customer’s perspective pays off in many ways. Most notably, it helps define value–the most important basis for creating a competitive advantage.

Price from a societal perspective

Price, at least in dollars and cents, has been the historical view of value. Derived from a bartering system (exchanging goods of equal value), the monetary system of each society provides a more convenient way to purchase goods and accumulate wealth. Price has also become a variable society employs to control its economic health. Price can be inclusive or exclusive. In many countries, such as Russia, China, and South Africa, high prices for products such as food, health care, housing, and automobiles, means that most of the population is excluded from purchase. In contrast, countries such as Denmark, Germany, and Great Britain charge little for health care and consequently make it available to all.

There are two different ways to look at the role price plays in a society: rational man and irrational man. The former is the primary assumption underlying economic theory, and suggests that the results of price manipulation are predictable. The latter role for price acknowledges that man’s response to price is sometimes unpredictable and pretesting price manipulation is a necessary task. Let us discuss each briefly.

Rational man pricing: an economic perspective

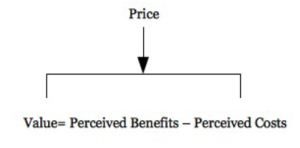

Basically, economics assumes that the consumer is a rational decision maker and has perfect information. Therefore, if a price for a particular product goes up and the customer is aware of all relevant information, demand will be reduced for that product. Should price decline, demand would increase. That is, the quantity demanded typically rises causing a downward sloping demand curve.

A demand curve shows the quantity demanded at various price levels (see Figure 9.2). As a seller changes the price requested to a lower level, the product or service may become an attractive use of financial resources to a larger number of buyers, thus expanding the total market for the item. This total market demand by all buyers for a product type (not just for the company’s own brand name) is called primary demand. Additionally, a lower price may cause buyers to shift purchases from competitors, assuming that the competitors do not meet the lower price. If primary demand does not expand and competitors meet the lower price the result will be lower total revenue for all sellers.

Since, in the US, we operate as a free market economy, there are few instances when someone outside the organization controls a product’s price. Even commodity-like products such as air travel, gasoline, and telecommunications, now determine their own prices. Because large companies have economists on staff and buy into the assumptions of economic theory as it relates to price, the classic price-demand relationship dictates the economic health of most societies. The Chairman of the US Federal Reserve determines interest rates charged by banks as well as the money supply, thereby directly affecting price (especially of stocks and bonds). He is considered by many to be the most influential person in the world.

Figure 9.2: Price and demand.

Irrational man pricing: freedom rules

There are simply too many examples to the contrary to believe that the economic assumptions posited under the rational man model are valid. Prices go up and people buy more. Prices go down and people become suspicious and buy less. Sometimes we simply behave in an irrational manner. Clearly, as noted in our earlier discussion on consumers, there are other factors operating in the marketplace. The ability of paying a price few others can afford may be irrational, but it provides important personal status. There are even people who refuse to buy anything on sale. Or, others who buy everything on sale. Often businesses are willing to hire a USD 10,000 consultant, who does no more than a USD 5,000 consultant, simply to show the world they are successful.

In many societies, an additional irrational phenomenon may exist–support of those that cannot pay. In the US, there are literally thousands of not-for-profit organizations that provide goods and services to individuals for very little cost or free. There are also government agencies that do even more. Imagine what giving away surplus food to the needy does to the believers of the economic model.

Pricing planners must be aware of both the rational as well as the irrational model, since, at some level, both are likely operating in a society. Choosing one over the other is neither wise nor necessary.

The marketer’s view of price

Price is important to marketers, because it represents marketers’ assessment of the value customers see in the product or service and are willing to pay for a product or service. A number of factors have changed the way marketers undertake the pricing of their products and services. (1)

- Foreign competition has put considerable pressure on US firms’ pricing strategies. Many foreign-made products are high in quality and compete in US markets on the basis of lower price for good value.

- Competitors often try to gain market share by reducing their prices. The price reduction is intended to increase demand from customers who are judged to be sensitive to changes in price.

- New products are far more prevalent today than in the past. Pricing a new product can represent a challenge, as there is often no historical basis for pricing new products. If a new product is priced incorrectly, the marketplace will react unfavorably and the “wrong” price can do long-term damage to a product’s chances for marketplace success.

- Technology has led to existing products having shorter marketplace lives. New products are introduced to the market more frequently, reducing the “shelf life” of existing products. As a result, marketers face pressures to price products to recover costs more quickly. Prices must be set for early successes including fast sales growth, quick market penetration, and fast recovery of research and development costs

Newsline: The risk of free PCs

There is no such thing as a free PC. However, judging from the current flood of offers for free or deeply discounted computers, you might think that the laws of economics and common sense have been repealed. In fact, all of those deals come with significant strings attached and require close examination. Some are simply losers. Others can provide substantial savings, but only for the right customers.

The offers come in two categories. In one type, consumers get a free computer along with free Internet access, but have to accept a constant stream of advertising on the screen In the other category, the customer gets a free or deeply discounted PC in exchange for a long-term contract for paid Internet services.

Most of these are attractive deals, but the up-front commitment to USD 700 or more worth of Internet service means they are not for everyone. One group that will find little value in the arrangement is college students, since nearly all schools provide free and often high-speed Net access. Others who could well end up losing from these deals are the lightest and heaviest users of the Internet. People who want Internet access only to read e-mail and do a little light Web browsing would likely do better to buy an inexpensive computer and sign up for a USD 10-per-month limitedaccess account with a service provider.

People who use the Internet a lot may also be poor candidates. That is because three years is a long commitment at a time when Internet access technology is changing rapidly. Heavy users are likely to be the earliest adopters of high-speed cable or digital subscriber line service as it becomes available in their areas. (34)

Review

- The chapter begins by defining price from the perspective of the consumer, society, and the business. Each contributes to our understanding of price and positions it as a competitive advantage.

- The objectives of price are five-fold: (a) survival, (b) profit, (c) sales, (d) market share, and (e) image. In addition, a pricing strategy can target to: meet competition, price above competition, and price below competition.

- Price should be viewed from three perspectives:

- the customer

- the marketer

- society

- Pricing tactics include new product pricing, price lining, price flexibility, price bundling, and the psychological aspects of pricing. The chapter concludes with a description of the three alternative approaches to pricing: cost-oriented, demand-oriented, and value-based.

Sources

(32): Greg Burns, “McDonald’s: Now, It’s Just Another Burger Joint,” Business Week, March 17, 1997, pp. 3- 8; Bill McDowell, “McDonald’s Falls Back to Price-Cutting Tactics,” Advertising Age, February 3, 1997, pp. 5-7; Michael Hirsch,”The Price is Right,” Time, February 10, 1997, p. 83; Louise Kramer, “More-Nimble McDonald’s is Getting Back on Track,”Advertising Age, January 18, 1999, p. 6; David Leonhardt, “Getting Off Their McButts,” Business Week, February 22, 1999, pp.84-85; Bruce Horovitz, “Fast-Food Facilities Face Sales Slowdown,” USA Today Wednesday, February 21 , 2001, p. 3B.

(33): Ginger Conlon, “Making Sure the Price is Right;’ Sales and Marketing Management, May 1996, pp. 92–93 Thomas T. Nagle and Reed K. Holden, The Strategy and Tactics of Pricing, 2nd ed., Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Prentice Hall, Inc. 1995; William C. Symonds, “‘Build a Better Mousetrap’ is No Claptrap;’ Business Week, February 1, 1999, p. 47; Marcia Savage, “Intel to Slash Pentium II Prices,” Company Reseller News, February 8, 1999, pp. 1, 10.

(34): Stephen H. Weldstrom. ” High Cost of Free PCs.” Business Week, September 13, 1999. p. 20; Steven Bruel. “Why Talk’s Cheap,” Business Week, September 13. 1999, pp. 34-36; Mercedes M. Cardona and Jack Neff, ” thing’s at a Premium,” Advertising Age, August 2. 1999, pp. 12-13.

(35): Pamela L. Moore, “Name Your Price-For Everything?” Business Week, April 17,2000, pp. 72-75; “Priceline.com to Let Callers Name Price,” Los Angeles Times, Nov. 9, 1999, p. 3; “Priceline to offer auto insurance,” Wall Street Journal Aug. 3, 2000, p. J2; “Priceline teams up with 3 phone co to sell long distance,” Wall Street Journal, May 2000, p. 16

References

- Thomas Nagle, “Pricing as Creative Marketing Business Horizons, July-August 1983, pp.14-19.

- Robert A. Robicheaux, “How Important is Pricing in Competitive Strategy?” Proceedings of the Southern Marketing Association 1975, pp. 55-57.