Learning Objectives

The objectives of this section is to help students …

- Understand the role of distribution channels

- Understand the flows in channels

Sam sightings are everywhere

The spirit of Sam Walton permeates virtually every corner of America. This small-town retailer has produced a legacy of US sales of USD 118 billion, or 7 per cent of all retail sales. In the US, Wal-Mart has 1,921 discount stores, 512 super centers, and 446 Sam’s Clubs. Wal-Mart recently challenged local supermarkets by opening their new format: Neighborhood Markets. Overall, they have more than 800,000 people working in more than 3,500 stores on four continents.

Today, Wal-Mart is the largest seller of underwear, soap, toothpaste, children’s clothes, books, videos, and compact discs. How can you challenge their Internet offerings that now number more than 500,000, with planned expansion of more than 3,000,000? Or the fact that Ol’ Roy (named after Sam’s Irish setter) is now the best-selling dog food brand in America? Besides Ol’ Roy, Wal-Mart’s garden fertilizer has also become the best-selling brand in the US in its category, as has its Spring Valley line of vitamins

So how do you beat a behemoth like Wal-Mart? One retail expert tackled this question in his autobiography. He suggests 10 ways to accomplish this goal: (a) have a strong commitment to your business; (b) involve your staff in decision making; (c) listen to your staff and your customers; (d) learn how to communicate; (e) appreciate a good job; (f) have fun; (g) set high goals for staff; (h) promise a lot, but deliver more; (i) watch your expenses; and (j) find out what the competition is doing and do something different. The author of this autobiography: Made in AmericaSam Walton. (36)

Introduction

This scenario highlights the importance of identifying the most efficient and effective manner in which to place a product into the hands of the customer. This mechanism of connecting the producer with the customer is referred to as the channel of distribution. Earlier we referred to the creation of time and place utility. This is the primary purpose of the channel. It is an extremely complex process, and in the case of many companies, it is the only element of marketing where cost savings are still possible

In this chapter, we will look at the evolution of the channel of distribution. We shall see that several basic functions have emerged that are typically the responsibility of a channel member. Also, it will become clear that channel selection is not a static, once-and-for-all choice, but that it is a dynamic part of marketing planning. As was true for the product, the channel must be managed in order to work. Unlike the product, the channel is composed of individuals and groups that exhibit unique traits that might be in conflict, and that have a constant need to be motivated. These issues will also be addressed. Finally, the institutions or members of the channel will be introduced and discussed.

The dual functions of channels

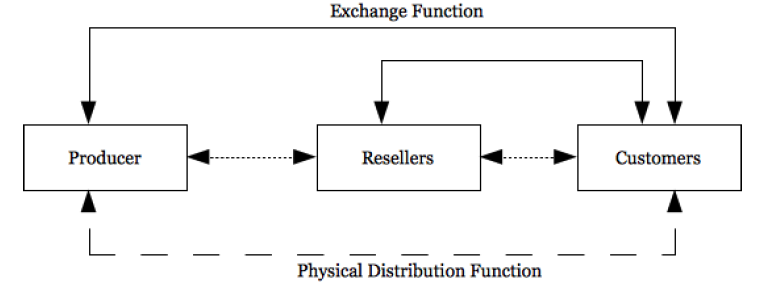

Just as with the other elements of the firm’s marketing program, distribution activities are undertaken to facilitate the exchange between marketers and consumers. There are two basic functions performed between the manufacturer and the ultimate consumer.1 (See Exhibit 31.) The first called the exchange function, involves sales of the product to the various members of the channel of distribution. The second, the physical distribution function, moves products through the exchange channel, simultaneously with title and ownership. Decisions concerning both of these sets of activities are made in conjunction with the firm’s overall marketing plan and are designed so that the firm can best serve its customers in the market place. In actuality, without a channel of distribution the exchange process would be far more difficult and ineffective.

The key role that distribution plays is satisfying a firm’s customer and achieving a profit for the firm. From a distribution perspective, customer satisfaction involves maximizing time and place utility to: the organization’s suppliers, intermediate customers, and final customers. In short, organizations attempt to get their products to their customers in the most effective ways. Further, as households find their needs satisfied by an increased quantity and variety of goods, the mechanism of exchange—i.e. the channel—increases in importance.

Figure 10.1: Dual-flow system in marketing channels.

The evolution of the marketing channel

As consumers, we have clearly taken for granted that when we go to a supermarket the shelves will be filled with products we want; when we are thirsty there will be a Coke machine 0r bar around the corner; and, when we do not have time to shop, we can pick-up the telephone and order from the J.C. Penney catalog or through the Internet. Of course, if we give it some thought, we realize that this magic is not a given, and that hundreds of thousands of people plan, organize, and labor long hours so that this modern convenience is available to you, the consumer. It has not always been this way, and it is still not this way in many other countries. Perhaps a little anthropological discussion will help our understanding.

The channel structure in a primitive culture is virtually nonexistent. The family or tribal group is almost entirely self-sufficient. The group is composed of individuals who are both communal producers and consumers of whatever goods and services can be made available. As economies evolve, people begin to specialize in some aspect of economic activity. They engage in farming, hunting, or fishing, or some other basic craft. Eventually this specialized skill produces excess products, which they exchange or trade for needed goods that have been produced by others. This exchange process or barter marks the beginning of formal channels of distribution. These early channels involve a series of exchanges between two parties who are producers of one product and consumers of the other.

With the growth of specialization, particularly industrial specialization, and with improvements in methods of transportation and communication, channels of distribution become longer and more complex. Thus, corn grown in Illinois may be processed into corn chips in West Texas, which are then distributed throughout the United States. Or, turkeys raised in Virginia are sent to New York so that they can be shipped to supermarkets in Virginia. Channels do not always make sense.

The channel mechanism also operates for service products. In the case of medical care, the channel mechanism may consist of a local physician, specialists, hospitals, ambulances, laboratories, insurance companies, physical therapists, home care professionals, and so forth. All of these individuals are interdependent, and could not operate successfully without the cooperation and capabilities of all the others.

Based on this relationship, we define a marketing channel as sets of interdependent organizations involved in the process of making a product or service available for use or consumption, as well as providing a payment mechanism for the provider.

This definition implies several important characteristics of the channel. First, the channel consists of institutions, some under the control of the producer and some outside the producer’s control. Yet all must be recognized, selected, and integrated into an efficient channel arrangement.

Second, the channel management process is continuous and requires continuous monitoring and reappraisal. The channel operates 24 hours a day and exists in an environment where change is the norm.

Finally, channels should have certain distribution objectives guiding their activities. The structure and management of the marketing channel is thus in part a function of a firm’s distribution objective. It is also a part of the marketing objectives, especially the need to make an acceptable profit. Channels usually represent the largest costs in marketing a product.

Flows in marketing channels

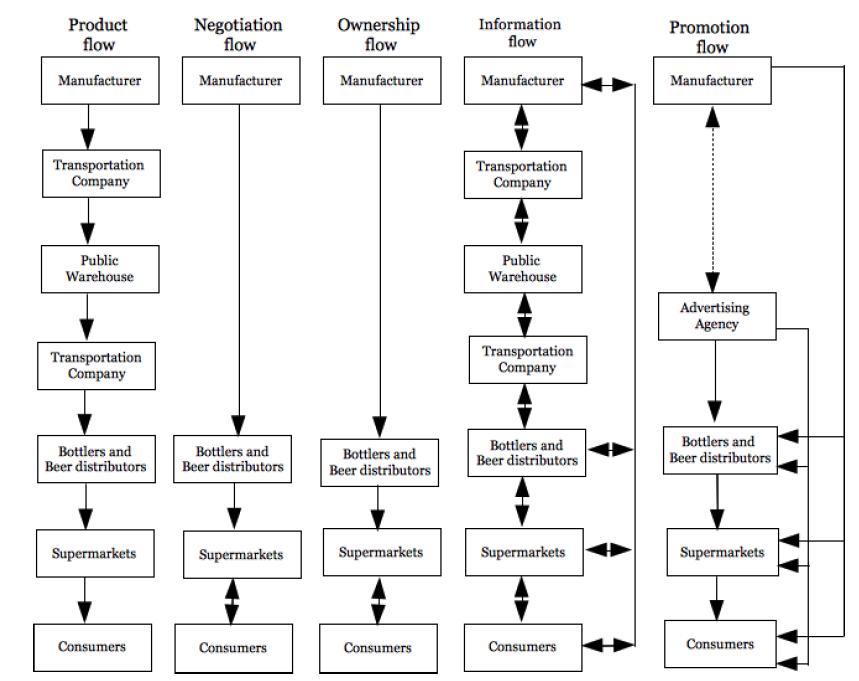

One traditional framework that has been used to express the channel mechanism is the concept of flow. These flows, touched upon in Exhibit 32, reflect the many linkages that tie channel members and other agencies together in the distribution of goods and services. From the perspective of the channel manager, there are five important flows.

- Product flow

- Negotiation flow

- Ownership flow

- Information flow

- Promotion flow

These flows are illustrated for Perrier Water in Figure 10.2.

The product flow refers to the movement of the physical product from the manufacturer through all the parties who take physical possession of the product until it reaches the ultimate consumer. The negotiation flow encompasses the institutions that are associated with the actual exchange processes. The ownership flow shows the movement of title through the channel. Information flow identifies the individuals who participate in the flow of information either up or down the channel. Finally, the promotion flow refers to the flow of persuasive communication in the form of advertising, personal selling, sales promotion, and public relations.

Figure 10.2: Five flows in the marketing channel for Perrier Water.

(Source: Bert Rosenbloom, Marketing Channels: A Management View, Dryden Press, Chicago, 1983, p.11.)

Functions of the channel

The primary purpose of any channel of distribution is to bridge the gap between the producer of a product and the user of it, whether the parties are located in the same community or in different countries thousands of miles apart. The channel is composed of different institutions that facilitate the transaction and the physical exchange. Institutions in channels fall into three categories: (a) the producer of the product–a craftsman, manufacturer, farmer, or other extractive industry producer; (b) the user of the product–an individual, household, business buyer, institution, or government; and (c) certain middlemen at the wholesale and/or retail level. Not all channel members perform the same function.

Heskett (2) suggests that a channel performs three important functions:

- Transactional functions: buying, selling, and risk assumption

- Logistical functions: assembly, storage, sorting, and transportation

- Facilitating functions: post-purchase service and maintenance, financing, information dissemination, and channel coordination or leadership

These functions are necessary for the effective flow of product and title to the customer and payment back to the producer. Certain characteristics are implied in every channel. First, although you can eliminate or substitute channel institutions, the functions that these institutions perform cannot be eliminated. Typically, if a wholesaler or a retailer is removed from the channel, the function they perform will be either shifted forward to a retailer or the consumer, or shifted backward to a wholesaler or the manufacturer. For example, a producer of custom hunting knives might decide to sell through direct mail instead of retail outlets. The producer absorbs the sorting, storage, and risk functions; the post office absorbs the transportation function; and the consumer assumes more risk in not being able to touch or try the product before purchase.

Second, all channel institutional members are part of many channel transactions at any given point in time. As a result, the complexity may be quite overwhelming. Consider for the moment how many different products you purchase in a single year, and the vast number of channel mechanisms you use.

Third, the fact that you are able to complete all these transactions to your satisfaction, as well as to the satisfaction of the other channel members, is due to the routinization benefits provided through the channel. Routinization means that the right products are most always found in places (catalogues or stores) where the consumer expects to find them, comparisons are possible, prices are marked, and methods of payment are available. Routinization aids the producer as well as the consumer, in that the producer knows what to make, when to make it, and how many units to make.

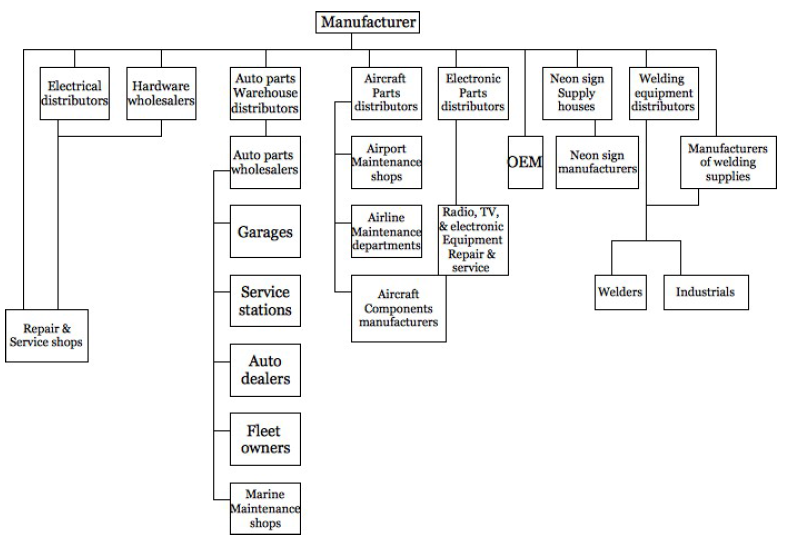

Fourth, there are instances when the best channel arrangement is direct, from the producer to the ultimate user. This is particularly true when available middlemen are incompetent, unavailable, or the producer feels he can perform the tasks better. Similarly, it may be important for the producer to maintain direct contact with customers so that quick and accurate adjustments can be made. Direct-to-user channels are common in industrial settings, as are door-to-door selling and catalogue sales. Indirect channels are more typical and result, for the most part, because producers are not able to perform the tasks provided by middlemen (See Exhibit 33).

Figure 10.3: Marketing channels of a manufacturer of electrical wire and cable.

Source: Edwin H. Lewis, Marketing Electrical Apparatus and Supplies,McGraw-Hill, Inc., 1961, p. 215.

Finally, although the notion of a channel of distribution may sound unlikely for a service product, such as health care or air travel, service marketers also face the problem of delivering their product in the form, at the place and time their customer demands. Banks have responded by developing bank-by-mail, Automatic Teller Machines (ATMs), and other distribution systems. The medical community provides emergency medical vehicles, out patient clinics, 24-hour clinics, and home-care providers. As noted in Figure 10.3 even performing arts employ distribution channels. In all three cases, the industries are attempting to meet the special needs of their target markets while differentiating their product from that of their competition. A channel strategy is evident.

Review

- The complex mechanism of connecting the producer with the consumer is referred to as the channel of distribution.

- Five “flows” are suggested reflect the ties of channel members with other agencies in the distribution of goods and services.

- A channel performs three important functions: (a) transactional functions, (b) logistical functions, and (c) facilitating functions.

- Channel strategies are evident for service products as well as for physical products.

- Options available for organizing the channel structure include: (a) conventional channels, (b) vertical marketing systems, (c) horizontal channel systems, and (d) multiple channel networks.

- Designing the optimal distribution channel depends on the objectives of the firm and the characteristics of available channel options.

Sources:

(36): Murra Raphel, “Up Against the Wal-Mart,” Direct Marketing, April 1999, pp. 82-84; Adrienne Sanders, “Yankee Imperialists,” Forbes December 13,1999, p. 36; Jack Neff, “Wal-mart Stores Go Private (Label),” Advertising Age, November 29,1999, pp. 1, 34, 36; Alice Z. Cuneo, “Wal-Mart’s Goal: To Reign Over Web,” Advertising Age, July 5 1999, pp. 1, 27.