Key Issues

- All teachers are language teachers.

- Language and content strengths and needs provide a foundation for creating learning objectives.

- Content objectives support facts, ideas, and processes.

- Language objectives support the development of language related to content and process.

- Objectives must be directly addressed by lesson activities.

As you read the scenarios below, think about how your classroom context might be like those of the teachers depicted. Reflect on how you might address the situations these teachers face.

Scenario 1

Mary Alvarez was concerned. Her fourth-graders, a mix of native English speakers and English language learners (ELLs) with a variety of different skills and knowledge, seemed to understand the math content she was teaching, but they could not express it in ways that would help them to pass the written math exit test for fourth grade. Their lack of appropriate math vocabulary and process writing skills made their explanations difficult to evaluate. Ms. Alvarez’s understanding was that, if students were exposed to language and grammatical structures, they would be able to pick them up. However, her students did not seem to be doing so with any consistency during her math lessons.

Scenario 2

Peter Morello conducted ongoing, formative assessment in his high school biology class. He closely monitored the students’ progress toward mastering the content objectives and incorporated scaffolding at every opportunity. He felt that his students were not really grasping the concepts he was teaching, and when it came time to present their understandings, the students had many spelling and grammar errors and could not adequately express what they had found during their lab investigations. When he mentioned this problem in the faculty lounge, other teachers agreed that it was an issue. It was not only the ELLs, however; many of the other students were not picking up what they read in their texts and they could not express themselves in grammatical English. Like some of the other content teachers, Mr. Morello felt that the English and English language learning (ELL) teachers should be addressing these issues with students while he focused on science content.

STOP AND DO

Before reading the chapter, discuss with your classmates why the students and the teachers in the scenarios may be having problems. What information or understandings can provide solutions for the teachers?

Background

Both teachers in the chapter-opening scenarios recognize that their students need language help. Like many teachers, however, they have misunderstandings about how language learning occurs, a lack of knowledge about how to integrate content and language, and no notion of why they should. Teachers can help students access the academic content of the class; however, if language is a barrier to access, then they must also consider ways to help learners access the language they need. Contrary to Ms. Alvarez’s belief in the scenario, students do not “absorb” language without scaffolding and focused attention, just like they need for learning content (Crawford & Krashen, 2007). A specific focus on central skills and concepts is critical to learning both language and content.

This specific focus on language is important in all classrooms, whether content is presented in an elementary classroom in a thematic unit or in a secondary classroom as a discrete subject. This focus is important because, as we outlined in Chapter 1, each content area has jargon, technical vocabulary, and genre that is specific to that content area. Because ELL and other language teachers may not be well versed in the vocabulary and discourses of all the content areas, regular classroom teachers are probably best suited to teach these types of language with the support of language educators. In essence, all teachers are language teachers to some extent, even if they teach the language of only one content area, as they often do at the secondary level.

Chapter 3 focused on understanding students’ needs, backgrounds, and interests. Although content standards and goals for specific grade levels are often prescribed in statewide curricula, the objectives and activities that help learners reach those goals can and should be based on what teachers discover about their students. This chapter focuses on integrating social and academic language needs into content lessons so that all students can access the academic content. An important aspect of teaching language across content areas and themes is understanding how to develop appropriate and relevant language objectives as part of lessons. The development of language objectives and activities that support the objectives is the main emphasis of this chapter.

Understanding Objectives

Different texts call learning objectives by different terms, but it is the idea behind them that is important rather than the exact label. In this text, objectives are statements of attainable, quantifiable lesson outcomes that guide the activities and assessment of the lesson. Objectives differ from goals and standards, which can also be called “learning targets” and are very general statements of learning outcomes. Objectives are also different from activities or tasks, which explain what the students will do to reach the objectives and goals. Objectives typically follow a general format, as outlined in the formula below:

“Students will be able to” + concrete, measurable outcome + content to be learned

The three parts of this formula are equally important. First, “students will be able to”—often abbreviated SWBAT—indicates that what follows in the objective are criteria against which a student’s performance can be evaluated after the lesson. Note that starting an objective with the words “Students will” is not the same as SWBAT because “Students will” indicates what activities the students will do rather than the outcomes that they are expected to achieve from participating in the activity. Second, the concrete, measurable outcome presents the criterion that the evaluation will focus on. The chart in Figure 4.1 presents a list of possible action verbs that can be used to state the measurable outcome. Finally, the third part of the objective states the exact content to be learned and sometimes also includes to what degree it should be mastered (100% accuracy, 9 out of 10 times, etc.).

| abstract activate adjust analyze arrange assemble assess associate calculate carry out categorize change classify compare compose |

contrast conduct construct criticize critique define demonstrate describe design develop differentiate direct discover distinguish draw |

dramatize employ establish estimate evaluate examine explain explore express formulate generalize identify illustrate infer interpret |

introduce investigate list locate modify name observe organize perform plan predict prepare produce propose rate |

recall recognize record relate reorganize repeat replace report research restate revise select sequence simplify sketch |

skim solve state summarize survey test theorize track translate use verbalize visualize write |

Figure 4.1 Measurable verbs.

Source: Adapted from Action Verbs for Learning Objectives © 2004 Education Oasis™ http://www.educationoasis.com

Content objectives

Most mainstream teachers are accustomed to writing content objectives. Content objectives support the development of facts, ideas, and processes. For example, in a unit about the Civil War, one of the content objectives might be:

- SWBAT name three of five central causes of the Civil War in writing.

Others might include

- SWBAT list the major battles of the Civil War.

or

- SWBAT recite the first section of the Gettysburg Address.

Which objectives the teacher chooses may depend on the dictates of standards, grade-level requirements, and curricula. Whatever criteria are used for choosing them, those objectives should be developed based on what students already know and need to know and provide a strong guide for the development of the rest of the lesson.

STOP AND DO

Look at the standards and other content requirements for teaching in your current or future area(s). Write one or more content objectives that might be appropriate for the students that you plan to or do teach. Refer to Figure 4.1 for action verbs. Then review others’ objectives and see what questions you still have about content objectives.[1]

Language objectives

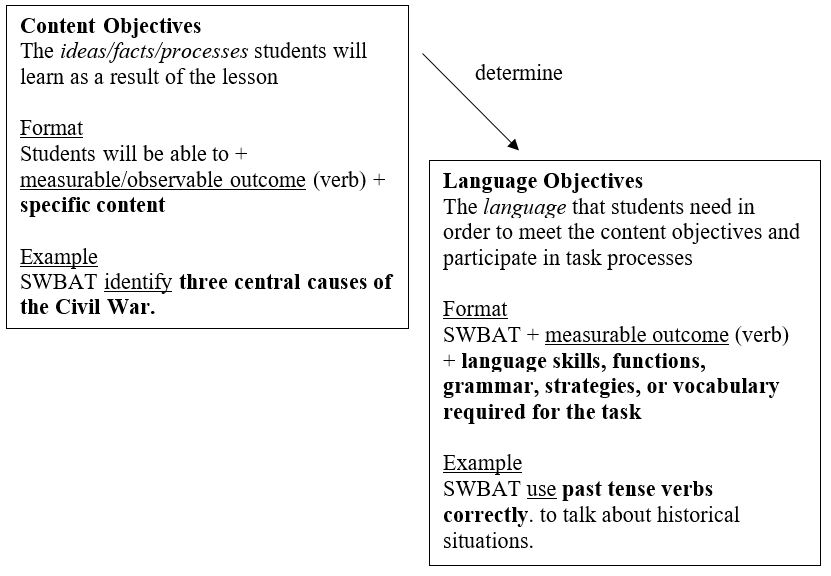

While content objectives emphasize facts, ideas, and content processes, language objectives support the development of language related to the content and process. This relationship is shown in Figure 4.2. Although some content standards and curricula do address general language and communication goals, language objectives are specifically based on helping students access the content of a particular lesson. Because there may be many language objectives that could help learners access the content of each lesson (too many to address in one lesson), they are also created based on the teacher’s knowledge of students’ current language skills and abilities.

Figure 4.2 The relationship between content and language objectives.

Constructing Language Objectives

The first step in creating language objectives is to determine social and academic language needs based on content objectives. Language needs can fall into these five general categories (adapted from Echevarria, Vogt, & Short, 2016):

- Vocabulary: Including concept words and other words specific to the content, for example, words that end in -ine, insect body parts, parts of a map, precipitation, condensation, and evaporation.

- Language functions: What students can do with language, for example, define, describe, compare, explain, summarize, ask for information, interrupt, invite, read for main idea, listen and give an opinion, edit, elicit elements of a genre.

- Grammar: How the language is put together (its structure), for example, verb tenses, sentence structure, punctuation, question formation, prepositional phrases.

- Discourse: Ways students use language, for example, in genres such as autobiographies, plays, persuasive writing, newspaper articles, proofs, research reports, speeches, folktales from around the world.

- Language learning strategies: A systematic plan to learn language, for example, determining patterns, previewing texts, taking notes.

For example, the chart in Figure 4.3 shows some of the language in these categories that students might need in order to meet the stated content objective in a lesson on the Civil War.

| Content Objective: SWBAT state three of five central causes of the Civil War in writing. |

||||

| Vocabularyslavery North South economy secession federal abolition |

Grammar Past tense Complete sentences |

Discourse Narrative and report genres |

Functions Identify main ideas. Make a statement. Summarize. Define words. Use cause and effect. Spelling. Arguing. |

Strategies Take notes. Listen strategically. |

Figure 4.3 Determining language needs.

STOP AND THINK

Can you think of more examples of the five kinds of language listed previously? Can you think of other types of language that students might need in order to meet the content objective in Figure 4.3?

Depending on the teacher’s understandings of her students’ language needs and on what she sees as the most important language elements to emphasize, she might choose one or more of the following language objectives for this lesson:

- SWBAT spell the following vocabulary correctly: economy, secession, federal, abolition.

- SWBAT listen carefully for main ideas from a reading on the Civil War.

- SWBAT use past tense verbs to write complete sentences.

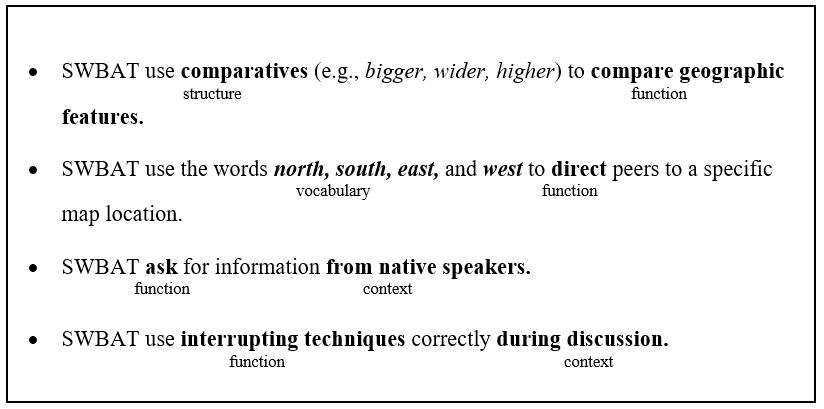

There are many variations on language objectives, and the basic formula presented above can be used for all of them. There are also variations on this basic formula that add context, grammatical structure, and other elements to the objectives. Examples are presented in Figure 4.4.

Figure 4.4 Sample language objectives.

Figure 4.5 demonstrates an abbreviated process for determining language objectives for a variety of content areas. The topic of the lesson is first established (column 1) and the content objective(s) are created (column 2). From the content objective(s), a list of the types of language needed to access the content is developed (column 3). Student backgrounds are considered (column 4), and then language objectives that address student needs are produced (column 5). Notice that the objective presents the language to be learned or used first, and then it addressed the context or conditions in which it will be learned or produced.

| Topic | Content Objective | Sample Language Needed | What Students Already Know | Possible Language Objective |

| Arctic animals | SWBAT identify the habitats of Arctic animals by writing the name and the place. | Vocabulary like the names of the animals and habitats, spelling, defining. | The names, but not the definitions, of the habitats. | SWBAT write the definitions of Arctic animal habitats. |

| Our Community | SWBAT describe five important community

landmarks. |

Adjectives, present tense, prepositions of location. | They can use many adjectives but need more. They know simple present tense. | SWBAT use prepositions of location accurately. |

| Ancient Greece | SWBAT explain three contributions to current life made by the ancient Greeks. | Past tense, present tense, sentence format, connectors (in addition, another, etc.). | They know how to make past and present tense sentences. | SWBAT use connectors correctly in oral and written texts. |

| Sports | SWBAT demonstrate the rules of American football. | Sequencing (first, second, third, next); modal verbs (can, can’t, should, have to, must); football vocabulary. | They have already learned the vocabulary. | SWBAT use sequencing words to explain a series of events or items |

| Argument | SWBAT compose a five-paragraph argumentative essay. | Essay format, paragraph format, sentence format, topic sentences, conclusions, logic, argument support. | They understand paragraphs and sentences, but they do not know about persuasion/

argument. |

SWBAT construct an argument with three reasons to support their position. |

| Graphs | SWBAT compare the effectiveness of pie charts, line charts, and bar graphs given specific data. | Comparatives; vocabulary such as graph, chart, data; present tense | They know the vocabulary. | SWBAT use comparatives to write present tense |

Figure 4.5 Sample objective development process.

STOP AND DO

Look at Figure 4.5. For each objective, underline the concrete, measurable outcome and circle the content to be learned. Check your answers with a partner.

Every content objective does not necessarily require a language objective, and some lessons do not have language objectives at all because all students can access the content with skills and vocabulary that they already possess. However, it is important to examine possible language barriers to content in every lesson and to address them if needed.

In summary, the important features of language objectives include the following:

- They derive from the content to be taught.

- They consider the strengths and needs of students.

- They present measurable, achievable outcomes.

STOP AND DO

First, review the objective(s) you wrote for the Stop and Do about content objectives above. List all of the potential language that students might need in order to access the information and achieve the objective(s). Then choose the most important language, without which students could not possibly access the content, and write one or more language objectives that address this language need.

Teaching to the Language Objectives

Creating language objectives is a good start for addressing the social and academic language needs of students, particularly ELLs, but equally important is that lesson tasks address the objectives. This chapter presents some guidelines for making sure that students meet the language objectives. Chapters 7–11 present specific ideas for teaching to language objectives in a variety of disciplines.

Guideline 1: Integrate language and content

Just as tasks that address content objectives are integrated into the whole lesson rather than being addressed one by one, language objectives should also be integrated into the lesson and not taught in isolation from it. For example, these objectives were chosen for the Civil War lesson:

- Content: SWBAT state three of five central causes of the Civil War in writing.

- Language: SWBAT use reading strategies to uncover main ideas from a reading on the Civil War.

The teacher could teach about the central causes of the Civil War, separately teach how to identify main ideas, and then hope that the students will apply their knowledge to their Civil War task. This process, however, is problematic in several ways. First, it indicates to students that language is separate from content when it is actually derived directly from the content. In other words, teaching the language objective without content removes much of the context for the language. Second, it breaks up the lesson into chunks, each of which constitutes a separate preparation for the teacher. This is neither an efficient use of the teacher’s and students’ time nor an effective way to teach language.[2] As noted in Chapter 1, some authors believe that all language is contextualized to some extent, but treating language separately from content takes away the specific context that gives the language meaning, making the language more difficult to understand and use.

A better choice is for the teacher to integrate the content and language. So, for example, while the students are looking for the causes of the Civil War in their textbooks, the teacher can ask them how they figure out what the causes are, and the students can make a list of strategies to find main ideas. They can practice together by finding the first cause of the Civil War and explaining to each other how they found it. This choice makes the lesson more efficient (by teaching the two objectives at the same time) and effective (helping students see how language and content are related and moving them toward reaching both objectives).

Guideline 2: Use pedagogically sound techniques

In the past, language was typically taught through drill and practice, exercises with few context clues, and mechanical worksheets. Research has found that these techniques are effective for very few students in very limited contexts. Effective language instruction, in addition to being integrated into content instruction, should meet the following basic criteria:

- It is authentic. This means that it comes from contexts that students actually work in and that it is not stilted or discrete just for grammar study. It is language that students need for a real purpose.

- Language is taught both explicitly and implicitly. Students are both directly exposed and indirectly exposed so they can use strategies to figure out some meaning on their own.

- It is multimodal. Students are exposed to language through different modes such as graphics, reading, and listening, and they can respond in text, drawing, and voice.

- It is relevant. Not all students in a class need all of the language instruction. The teacher can choose to whom the lesson is aimed (small groups, individual students, the whole class) to make it relevant.

- It is based on interaction. Collaboration and cooperation help learners test their assumptions about language.

- You as a language teacher. How are you, or will you be, a language teacher? Think about the ways you and your students use or will be required to use language in your classroom. What do these uses mean for your teaching?

- Choosing modes. Think about a lesson you have observed or taught. How can you include more modes so that students are exposed to language in a variety of ways?

- Meeting the standards. Choose one of the content standards from your current or future grade level or content area. Develop one or more content objectives and then create language objectives for the same standard.

- Break down language. Choose a grammar point, language function, or discourse. Using any resources that you need to, list all the aspects of your choice and describe how you might use steps to teach your choice to your current or future students.

- Find state and national standards by content area on the Education World website at http://www.educationworld.com/standards/index.shtml. ↵

- To decontextualize means to consider something alone or take something away from its context. ↵

- In addition to the techniques and strategies described in this text, others can be found in many excellent guides. See, for example, Herrell and Jordan’s (2016) Fifty Strategies for Teaching English Language Learners (5th edition) and Making Content Comprehensible for English Learners: The SIOP Model (5th edition) by Echevarria, Vogt, and Short (2016). ↵

Guideline 3: Break down the language

Each language objective can actually imply a variety of smaller topics. For example, for students to learn past tense, they have to understand what it means in a time sense and also that there are regular and irregular past tense verbs (e.g., those with -ed added, those with alternative changes), different spellings (e.g., go/went), and different pronunciations (e.g., sometimes the -ed ending is pronounced “ed” and sometimes it is pronounced “t”). As with any content, the instructional approach can go whole to part or part to whole or both ways, depending on how students learn best. For example, the teacher might have students read a passage and ask how we know when the events happened (whole) and then review the various aspects of past tense (parts). Or the teacher and students can point out the different aspects of past tense verbs in a required reading first and then work toward a more general understanding of how it helps us know when events occurred. Either way, the parts of past tense should be examined in light of their use in class content.[3]

Figure 4.6 summarizes these three basic guidelines for language instruction. Additional guidelines are presented throughout this book.

| Guideline | Example |

| Integrate language and content | Contextualize the language instruction by using content as the language source. |

| Use pedagogically sound techniques | Language instruction should be authentic, multimodal, both explicit and implicit, relevant, and based in interaction. |

| Break down the language | Teach wholes and parts to address the different learning needs of students. |

Figure 4.6 Basic guidelines for helping students meet language objectives.

STOP AND THINK

After reading the chapter, what would you tell the teachers in the chapter-opening scenarios to help them with their concerns?

Conclusion

Every teacher is a language teacher, at least in part, because the language of the content areas requires students to learn social and academic language in order to access the content. Teachers can use their content objectives, which support facts, ideas, and processes, to determine language objectives, which support the development of language related to content and process. Then, by following principles of good pedagogy, teachers can integrate the language and content in lesson activities. Following this process helps make learning more efficient and effective and ensures that all students have a chance to succeed. As crucial as this is, the next chapter shows that there are additional important components of lesson design that teachers can master in order to help all students achieve.

Extensions

For Reflection

For Action

Extensions

Crawford, J., & Krashen, S. (2007). English learners in American classrooms: 101 questions, 101 answers. New York: Scholastic.

Echevarria, J., Vogt, M., & Short, D. (2016). Making content comprehensible for English learners. Boston, MA: Pearson/Allyn & Bacon.