Key Issues

- English texts and tasks, with their abundance of idioms, figurative language, imagery, and symbolism, present challenges for English language learners (ELLs).

- In our multimodal world, students must learn a variety of skills to identify, interpret, analyze, and communicate through a range of modes, media and symbols.

- The language arts include reading, writing, listening, speaking, viewing, and visually representing.

- Educators need to affirm and draw on the different literacy practices that students develop in and out of school.

- Early elementary grades focus on learning to read; later the focus is on reading to learn.

- Students benefit from receiving extensive and varied vocabulary instruction.

Read the scenario below and think about what the teacher has learned.

Scenario

It is 9:45 p.m. and Jeff Rosenfeld, a second-grade teacher, has only three more interactive journals to respond to; he takes a sip of his coffee. Last weekend had been a busy time for his students, as evidenced by their journal entries. Opening up the journal of Pierre, an ELL student from Togo, Jeff read the entry. Pierre, a native French speaker, had talked about attending church with his parents last weekend and then playing with friends he had made in his neighborhood. After writing a reply in which he modeled appropriate word order, Jeff jotted the following on a separate piece of paper:

Language Objectives for Pierre:

- Word order: (1) sentences: subject before verb; (2) questions: use of “do” or “did” with verb and placement of subject

- Tense: work on simple past tense (regular forms first: play → played; irregular forms later: go → went). Journal showed all present tense. This will be useful in social studies, too.

- Social studies: Allow Pierre to use simple past in social studies for now. As he demonstrates mastery, begin teaching present perfect and past perfect in stages.

Tomorrow, Jeff will use this information to plan the coming week’s whole-group and targeted small-group language lessons.

STOP AND THINK

Before reading the chapter, imagine three siblings from the Ukraine. During their first month in school, each student participated in the reading and discussion of one of the following books:

- Ekaterina (kindergarten): The Very Hungry Caterpillar (Carle)

- Misha (6th grade): Hatchet (Paulsen)

- Pavel (11th grade): Beloved (Morrison)

What language and literacy skills will Ekaterina, Misha, and Pavel need in order to access, understand, and participate in classroom activities? How can teachers prepare students in the early stages of language proficiency so that they can benefit from the discussion of these and other books?

English Language Arts:

Preparing Students for the Literacy Demands of Today and Tomorrow

Language and literacy development can be seen as a continuous process that starts at birth with a child’s earliest experiences with language. Observations of young children show that the development of oral language and literacy are interrelated processes. As children manipulate books, pencils, and papers, they begin to assume the roles of readers and writers in their everyday play. These early experiences in constructing meaning from text are part of what is called emergent literacy. Later, instruction in the early grades focuses on teaching students how to decode and produce written texts. As students leave the primary grades, the emphasis shifts to comprehension of increasingly complex texts in language arts and other content areas. This change of emphasis, from learning to read to reading to learn, may present many challenges for ELLs because they are learning language and content simultaneously.

potential challenges for ELLs in the English language arts classroom include:

- English texts have an abundance of idioms, figurative language, imagery, and symbolism.

- Students may not have practice in forming, expressing, and supporting their opinions about a literary work.

- Students may not be familiar with drawing conclusions, analyzing characters, and predicting outcomes.

- Texts use a variety of regional U.S. dialects as well as Middle and Old English.

- Students may lack familiarity with text structures and features.

- English texts have large quantities of unfamiliar vocabulary, homonyms, homophones, and synonyms.

- Students need to become familiar with grammar usage and with many of the exceptions to the rules found in any language.

- ELLs may not be familiar with terminology and routines associated with the writing process: drafting, revising, editing, workshop, conference, audience, purpose, or genre.

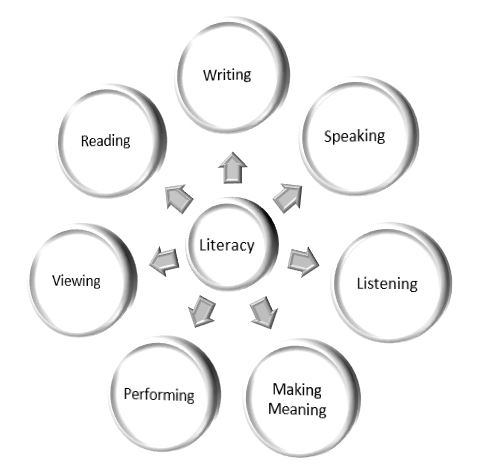

Language arts have traditionally focused on the four language domains of listening, speaking, reading, and writing, including language conventions such as punctuation, spelling, and grammar usage. Recently, however, a broader view of literacy includes a wide range of skills and abilities related to reading, writing, listening, speaking, viewing, and performing (CCSS, 2010). In addition, ongoing innovations in technology have brought forth novel ways in how people make meaning. Thus, “literacy” also includes making meaning from different modes of communication, as depicted in Figure 10.1.

Figure 10.1 A broader view of literacy.

This broader view of literacy, also referred as “multiliteracies” or “new literacies,” assumes that individuals “read” the world and make sense of information by means other than traditional reading and writing. These multiliteracies include linguistic, visual, audio, spatial, and gestural ways of meaning-making. Central to the concept of multiple literacies is the belief that individuals in a modern society need to learn how to construct knowledge from multiple sources and modes of representation.

Multiliteracies

In 1994, a group of ten educators from a variety of different nations and backgrounds met in New London to discuss literacy in regards to changes in students’ lives, technology, the workplace, language, and the globalization of society (Cazden et al., 1996). The New London Group realized that a changing world coupled with ongoing innovations in technology required changes in how we think about literacy and school literacy. As a result, they coined the term “multiliteracies” to describe the “multiplicity of communications channels and media [and] the increasing salience of cultural and linguistic diversity” (Cope & Kalantzis, 2000, p. 5).

The idea of literacies as “multiple” derives from the view that “there are many forms of literacy that vary across time and communities—that literacy is a social practice, rather than a set of reading and writing skills to be acquired” (Cervetti, Damico & Pearson, 2006, p. 379).

Several national learning standards and guidelines include goals that reflect a consideration of multiliteracies, for example the Common Core State Standards for English Language Arts & Literacy in History/Social Studies, Science, and Technical Subjects ([CCSS] 2010); National Coalition for Core Arts Standards (2014); standards from the National Council of Teachers of English/International Reading Association (2012); and Center of Applied Special Technology’s Universal Design for Learning Guidelines (2011).

For example, the sixth writing standard in the CCSS, “Use technology, including the internet, to produce and publish writing and to interact and collaborate with others,” emphasizes the use of technology to support literacy development. Used alongside other standards, it is possible to consider how technology and writing objectives can come together to actively engage all students and prepare them to use diverse technological tools. The exploration of new technologies in a structured, supportive environment can afford students the confidence to explore new technology tools on their own, as the tools are relevant to their lives.

However, we must be aware of the dangers of the “digital native” myth. In spite of research suggesting that many students, particularly teenagers, lead “tech-saturated lives,” not all our students are highly skilled in the use of new literacies or have access to technology. In other words, while some students might have plenty of access to new technologies, they might not be very skilled with online research and comprehension. In addition, in spite of the increasingly pervasive use of online textbooks by schools and districts, some students may have limited access to the Internet and technology at home.

New Literacies

The ongoing emergence of different digital technologies and new media has led to fundamental shifts in how people read, write, and communicate. Examples of new media include web-based applications for designing presentations (e.g., with Prezi, Canva, or Keynote), interactive video games (e.g., Minecraft, Bakugan, Defenders of the Core, Terraria), and online social platforms (e.g., Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, Twitter). Each new technology demands new literacy skills. The Internet, for example, requires an increasing skill set related to reading information found on websites, writing email messages, and posting to blogs (Coiro & Dobler, 2007). Many adolescents spend considerable time in online social spaces and using multimedia applications on digital devices. These activities generate an expanding number of new literacies, such as creating and sharing personal videos using applications like Vine and Vimeo (Munger, 2016).

STOP AND THINK

What new literacies do you currently use? What are some of the new literacies you would like to learn how to use? What new literacies are being used in the school where you teach or hope to teach?

Multimodalities

The theory of multimodality is informed by social semiotics—the field of study related to understanding how people construct meaning from signs and symbols in ways that reflect socially- and culturally-ascribed meanings and practices (Halliday, 1978). Examples of different modes include dance, painting, photography, computer-based communications, and written language. Multimodality acknowledges that communicating an idea so that others will understand it clearly may not be possible through one single mode alone (Jewitt & Kress, 2003).

A text can be defined as multimodal when it combines two or more semiotic systems. There are five semiotics systems:

| Audio | Includes aspects such as volume, pitch and rhythm of music and sound effects |

| Gestural | Includes aspects such as movement, speed, and stillness in facial expression and body language |

| Linguistic | Includes aspects such as vocabulary, generic structure, and the grammar of oral and written language |

| Spatial | Includes aspects such as proximity, direction, position of layout, and organization of objects in space. |

| Visual | Includes aspects such as color, vectors and viewpoint in still and moving images |

Everyday examples of multimodal texts include:

- A webpage that combines elements such as sound effects, oral language, written language, music, and images.

- An opera performance that combines music, dancing, gestures, and oral language.

- A textbook that combines textual and visual elements arranged on individual pages organized in a systematic manner.

For students to be successful in understanding multimodal texts, they will need to be able to “read” the multiple modes comprising each text.

If English learners are to achieve and succeed in the English language arts classroom, educators need to affirm and draw on the different literacy practices that students develop in and out of school. As we prepare students to achieve academically, we must not lose sight of the need to prepare students to succeed beyond the school walls. Students today are not only exposed to printed materials and TV, they are also now part of an increasingly multisensory world incessantly vying for students’ attention via movies, multimedia graphics, radio, music, the Internet, text messaging, cell phones, and computers. As we prepare students for a world that is experiencing an unprecedented technological revolution, we must not lose sight of the existence of multiple and evolving forms of literacy.

Effective Literacy Practices for ELLs in the Elementary Grades

Determining what is best for all students, including ELLs, depends on many factors, including: teachers’ own perspectives and experiences; school, district, and state curricula; the kinds of programs and supports available to the students; and the needs and strengths of the students. In this section, we first discuss key elements to consider (in addition to literacies and modalities) when developing a literacy program for elementary classrooms with ELLs. This discussion is followed by effective prereading and reading strategies for ELLs. Reading strategies are grouped around two broad categories: beginning readers and intermediate readers.

When planning literacy instruction for ELLs, educators need to consider their unique strengths and needs, including their distinctive backgrounds and experiences. In addition, teachers might want to consider the following elements when developing a successful literacy program.

Theoretical Orientation

Deciding on the teacher’s theoretical orientation to reading instruction (e.g., phonics approach, skills approach, whole-language approach, biliteracy) is a very important first step to guide the program. This does not necessarily mean that only one perspective needs to be adopted. Successful teachers of ELLs are often very creative and integrate different perspectives and approaches.

Language-Rich Environment. Surrounding ELLs with ample opportunities to hear and use language for meaningful purposes fosters the acquisition of English and the affirmation and acquisition of English through the native language, depending on the kind of program. Continuous modeling, ongoing feedback, a stress-free environment, and reasons to use the target language through the use of multimodalities all help students become better language users.

Meaningful Literacy. Learning how to read and write should not be equated with disconnected skill-and-drill practices. On the contrary, literacy learning should happen when students are engaged in actual, meaningful literacy acts within real-life environments.

Culturally Relevant Literacy Practices. Cultural practices are central to literacy learning. These practices play a tremendous role not only in how people learn to communicate orally or in written form but also in shaping the thinking processes of individuals. A classroom environment that acknowledges, responds to, and celebrates different literacy practices offers students opportunities to benefit, in a just and equitable manner, from the schooling experience.

Additive Perspective on Language

As mentioned throughout this book, the key is to consider students’ languages as resources. Even when instruction is only delivered in English, the goal should be to add English to students’ linguistic repertoire, not to replace it. Learning a second language should not be equivalent to losing the first language. On the contrary, additive bilingualism is promoted when students’ first languages and cultures are affirmed and developed. Additive bilingualism is linked to self-esteem, increased cognitive flexibility, and higher levels of proficiency in the second language.

Emphasis on Academic Language

The development of academic English needs to be an instructional goal for ELLs starting in the earliest grades. Students benefit from having deliberate academic language instruction done consistently and simultaneously during language arts and content-area instruction.

Reading Strategies

Prereading Strategies

Engaging students in prereading activities is one of the most successful strategies for motivating them to read and to activate and build their background knowledge on topics or concepts contained in the reading selection. Activation of relevant knowledge is extremely important for ELLs, who might not feel confident about their ability to read in English. In addition, prereading activities can serve as a vehicle to elicit students’ reactions and feelings about ideas and issues contained in the material to be read before confronting those issues in the text. See Figure 10.2 for selected strategies that have proven to be helpful to many teachers of ELLs.

| Strategy | Description |

| Anticipation guides | Can be designed as a list of three to five statements related to concepts or issues with which students are asked to agree or disagree. |

| Discuss critical terms and concepts | Identify and discuss important terminology, concepts and grammatical structures beforehand by using visuals or brainstorming meanings. |

| Establish a purpose for reading | Explaining the purpose of the reading selection often helps students focus by understanding why they are reading. |

| Field trips, films, and videos | Field trips are ideal activities to build background knowledge and vocabulary on a topic. Film clips and videos provide a visual context and help build schema. |

| Graphic organizers | Can be used to record prior knowledge about a concept, topic, or book. |

| KWL chart | Often used as a whole-group activity; helps students activate prior knowledge, identify areas of interest, and reflect on their learning. You can use the following headings: What I Know, What I Want to Know, What I Learned. |

| Making predictions | Give students the title of the book or text and show some pertinent visuals. Based on this information, have students make two or three predictions as to what they think the book or text is about. |

| Preview/simplified text summary | A preview presents the gist of the longer text and is written using relatively simple sentence constructions. Visuals or graphics are also helpful. |

Figure 10.2 Examples of prereading strategies for developing motivation, purpose, and background knowledge.

Reading Strategies for Beginning Readers

Beginning English readers, whether ELLs or not, are starting to make meaning from text. While some ELLs might need to be reminded to read from left to right and top to bottom, others might be starting to comprehend the text beyond the sentence level. Beginning readers, regardless of their age, need more familiarity and interaction with a variety of texts. See Figure 10.3 for a list of successful practices to support beginning readers.

| Strategy | Explanation |

| Choral reading | During choral reading, all students read aloud from the same selection under the direction of the teacher or leader. It helps students improve sight vocabulary and develop effective read-aloud skills. |

| Guided reading | Students are grouped at similar reading levels read under the guidance of their teacher. When students encounter difficulty reading aloud, the teacher offers explicit instruction to help them better decode or comprehend the text. |

| Language experience approach | Children dictate their stories to an adult or older student based on their personal experiences. Through this approach, students provide the text and the topics that will be the basis for reading instruction. |

| Literature circles | This student-centered collaborative strategy affords students opportunities to participate actively in the selection, reading, and discussion of a book. Because student members of the circle each have a role with corresponding responsibilities, students take ownership of their learning. |

| Predictable and pattern books | These books offer students opportunities to anticipate or predict what is next because of the patterned structure in the book. Books have repeated segments that are easily learned and allow children to read along with their teacher. |

| Reader’s theater | Students perform a dramatic presentation of a written work in script form. It helps students perfect their fluency and speaking skills. |

| Shared reading with big books | Children join in the reading of a big book or other enlarged text as guided by a teacher. The teacher points at each word as children read together. This offers children opportunities to participate and behave like readers. |

| Story mapping | A story map is a visual representation of the settings or the sequence of major events and action of the characters in the story. This strategy helps students visualize story characters, events, and settings and also helps them develop a sense of story. |

Figure 10.3 Strategies for beginning readers.

Strategies for Intermediate Readers

Intermediate readers are more familiar with reading a variety of texts for a variety of purposes. They can read with greater fluency because they have a larger sight vocabulary. However, they still have difficulty reading texts, particularly if the texts are about unfamiliar topics and have many new vocabulary words and sentence level constructions. Like their beginning reader counterparts, intermediate readers can benefit from supporting reading strategies like the ones listed in Figure 10.4.

| Strategy | Explanation |

| Cognitive mapping | This graphic drawing summarizes a text and helps readers with comprehending and remembering what they have read. |

| Directed reading-thinking activity (DR-TA) | This strategy asks students to make predictions about a text and then reread to confirm or refute their predictions. Doing so encourages students to be active and thoughtful readers, thus enhancing their comprehension. |

| Individual student conference | This strategy involves one-on-one conferences with students and is designed to gather information about each student as a reader and to provide direct, explicit, and targeted support. |

| Learning logs | Via this personalized learning strategy, students record their responses to reading challenges. Each log is a unique record of the child’s thinking and learning over time. |

| Literature response journals | Encourage students to draw, write, and talk about the books, poems, plays, or any other text they read. Through journaling, students experiment with a variety of writing skills and genres. |

| Think-alouds | Readers are asked to stop at various points during their reading and think aloud about the processes and strategies they are using as they read. This strategy allows teachers to observe students’ thinking aloud during reading to assess comprehension and inform instruction. |

Figure 10.4 Strategies for intermediate readers.

Key Elements for Improving Adolescent Literacy

There are important differences between teaching literacy to young children and to adolescents. These differences are more pronounced when teachers are working with ELLs. In the early grades, both ELLs and native English speakers are learning to read and write in English; in middle school and beyond, the focus shifts from literacy skills to the learning of academic content knowledge, skills, and ways of thinking. At the secondary level, there are fewer curricula and materials for ELLs and fewer content-area teachers prepared to address the needs of high school ELLs. Finally, the complexity of the texts, tasks, tests, and teachers’ explanations can be overwhelming for students who are learning a new language and adapting to a new culture, and at the same time trying to achieve in the content areas. Fisher, Rothenberg, and Frey (2007) compiled a list of strategies based on the findings from Reading Next: A Vision for Action and Research for Middle and High School Literacy (Biancarosa and Snow, 2006) completed for the Carnegie Corporation. This report, written by a panel of experts, identified 15 recommendations for addressing the needs of struggling adolescent readers and writers. One main point highlighted by Reading Next is the need to expand the efforts placed on literacy in the early grades (e.g., Reading First) to include acquiring literacy skills that can serve youth for a lifetime. Figure 10.5 presents nine important strategies from this report and their implications for effective reading instruction with adolescent ELLs.

| Instructional Practice | Explanation | Focus on ELL |

| 1. Direct, explicit comprehension instruction | Teach the strategies and processes that proficient readers use to understand what they read. |

|

| 2. Diverse texts | Use texts at a variety of difficulty levels and on a variety of topics. |

|

| 3. Effective instructional principles embedded in content | Use content-area texts in language arts classes and teach content-area-specific reading and writing skills in content-area classes. |

|

| 4. Intensive writing instruction | Form bridges to the kinds of writing tasks ELLs will have to perform in high school and beyond. |

|

| 5. Motivation and self-directed learning | Build motivation to read and learn and provide students with the instruction and supports needed for independent learning tasks that they will face after graduation. |

|

| 6. Ongoing formative assessment | Learn how ELLs are progressing under current instructional practices. |

|

| 7. Strategic tutoring | Provide students with intense individualized reading, writing, and content instruction as needed. |

|

| 8. Technology use | Use technology both as a tool and a topic for language and literacy instruction. |

|

| 9. Text-based collaborative learning | Encourage interaction among student around a variety of texts. |

|

Figure 10.5 Key elements of effective reading instruction for ELLs.

Source: Adapted from Language learners in the English classroom by D. Fisher, C. Rothenberg, and N. Frey. Copyright (2007) by the National Council of Teachers of English. Reprinted with permission.

Effective Writing Instruction for ELLs

Writing well in English is one of the most difficult skills for ELLs to master. Many ELLs continue acquiring vocabulary and syntactic competence in their writing throughout their lives. Students may show varying degrees of English language acquisition, and not all second language writers have the same difficulties or challenges. Teachers should be aware that ELLs may not be familiar with terminology and routines often associated with writing instruction in the United States, including the writing process, drafting, revision, editing, workshop, conference, audience, purpose, or genre. Certain elements of discourse, particularly in terms of audience and persuasion, may differ across cultural contexts. The same is true for textual borrowing and plagiarism. Figure 10.6 depicts 11 key elements that have proven effective for helping students learn to write well and to see writing as a tool for learning. These elements are based on the work done by Graham and Perin (2007) and Fisher, Rothenberg, and Frey (2007).

| Instructional Practice | Explanation | Focus on ELL |

| 1. Collaborative writing | Use instructional arrangements in which students work together to plan, draft, revise, and edit their writings. |

|

| 2. Inquiry activities | Engage students in analyzing data to help them develop ideas and content for a particular writing task. |

|

| 3. Prewriting | Engage students in activities designed to help them generate and organize their ideas for compositions. |

|

| 4. Process writing approach | Integrate a variety of writing activities in a workshop that focuses on extended writing opportunities, writing for authentic audiences and purposes, personalized instruction, and cycles of writing. |

|

| 5. Sentence combining | Teach students to construct increasingly complex, sophisticated sentences. |

|

| 6. Specific product goals | Assign students specific, reachable goals for the writing they will complete. |

|

| 7. Study of models | Provide students with opportunities to read, analyze, and emulate models of good writing. |

|

| 8. Summarization | Explicitly and systematically teach students to summarize texts. |

|

| 9. Word-processing skills and tools | Use computers and other kinds of technology as instructional supports for writing assignments. |

|

| 10. Writing for content learning | Use writing as a tool for learning content material. |

|

| 11. Writing strategies | Teach students strategies to plan, revise, and edit their compositions. |

|

Figure 10.6 Key elements of effective writing instruction for ELLs.

Source: Adapted from Language learners in the English classroom by D. Fisher, C. Rothenberg, and N. Frey. Copyright (2007) by the National Council of Teachers of English. Reprinted with permission.

The Language of English Language Arts

English language learners face a daunting task. They must acquire a multifaceted knowledge of the English language as they learn demanding grade-level content-area knowledge. They must do all this while native-English-speaking peers continue to increase their knowledge of the English language and its use and application in the content areas. ELLs have a steep path ahead of them in playing catch-up with their peers in a relatively short time. As they learn new vocabulary and language features with their peers, they also have to learn the social and academic language that their peers have learned since they entered school—and even earlier. ELLs need explicit and systematic practice to develop a competent command of the language of school, including the many features of academic language. Following is a brief outline of the standards under the English Language Arts (ELA) CCSS and their influence on shaping academic language. Finally, a discussion of the features of academic language in the English language arts classroom is included.

English Language Arts Common Core State Standards

The CCSS outline four strands of ELA instruction: reading, writing, listening/speaking, and language. These standards were designed to be taught concurrently and dictate increasing grade-level expectations. Under these standards, students who are college and career ready will be able to:

- Read, comprehend and analyze complex texts.

- Read texts across many content areas.

- Formulate arguments.

- Identify a speaker’s argument and point of view.

- Ask pertinent questions.

- Use academic vocabulary.

- Reference sources.

- Complete meaningful research and in-depth study.

- Share knowledge through speaking and writing.

- Cite specific evidence.

- Use technology to enhance communication.

- Seek to understand different cultural perspectives.

If English learners are going to reach these standards, Gottlieb & Ernst-Slavit (2014) indicate that their teachers will have to be aware of the following aspects:

- Features of academic language, from vocabulary, phrases and expressions to sentence level structures and a variety of diverse discourse or text types;

- Challenges that students will encounter along the way, such as understanding the subtleties of diverse texts, idiomatic expressions, and unique usages;

- Compatibility of the backgrounds and experiences of students with the texts required for a particular task.

The move towards standards-based teaching and learning is a national effort to improve educational success for all students; it is based on the assumption that all learners can reach higher levels of achievement if “expectations for all students are raised, standards are clearly defined, instruction and classroom assessment are differentially planned, leadership supports learning, and students are held accountable for their performance” (Gottlieb & Ernst-Slavit, 2014: 168).

STOP AND DO

Think back to Chapter 1 where you read about the different aspects of academic language: vocabulary, sentence level structures, discourse types, and language functions. Add two or three additional examples for each category in the chart below that are recurrent in the English language arts classroom.

| Aspect(s) of Language | Examples |

| Vocabulary | simile |

| Sentence level structures | hyperbole |

| Discourse types | argumentative essay |

| Language functions | argue |

Word/Phrase Level

The difference between the right word and almost the right word is the difference between lightning and a lightning bug.

—Mark Twain (1987)

As the Twain quote indicates, one of the most important challenges facing ELLs is the acquisition of the vocabulary needed to actively and successfully participate in all facets of school. ELLs encounter thousands of different words in texts, group work, classroom discussions, and tests, just to mention a few, and they need to learn many of them in a short time!

Harvard professor Catherine Snow (2005) concludes that, by the time middle-class students with well-educated parents are in third grade, they probably know 12,000 English words; she adds that, ideally, students should know 80,000 words by the time they graduate from high school. If some students are learning only 75% as fast as their peers, then huge deficits can be accrued.

Like other content areas, the English language arts classroom has its own set of general, specialized, and technical academic vocabulary. Figure 10.7 presents selected examples.

| Vocabulary Type | Definition | Examples | |

| General academic vocabulary | Terms used in content areas in addition to English language arts |

|

|

| Specialized academic vocabulary | Terms associated with English language arts |

|

|

| Technical academic vocabulary | Terms associated with a specific English language arts topic (e.g., Greek drama) |

|

|

Figure 10.7 Examples of vocabulary types in English language arts.

Vocabulary teaching strategies

Students can learn and use new words if they have daily opportunities to practice their newly acquired vocabulary. Students gain a deeper understanding of the meaning of words and their relationship to other words when explicit vocabulary instruction is presented daily via diverse strategies that target group of words. Selected teaching vocabulary strategies for all students are presented below.

- Root words. Students learn high-frequency roots from Latin or Greek (see Chapter 8 for examples). Students collect words with the roots and learn their meanings.

- Personal vocabulary journal. Students select new words and concepts and record them.

- Word games and word play. Games are fun ways to have students practice new words.

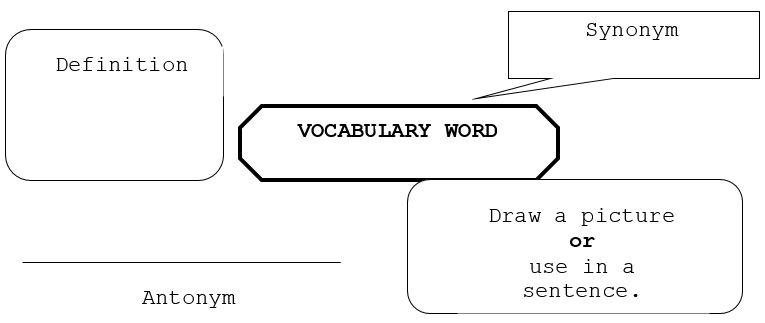

- Word or concept maps. A graphic organizer is created for each new word. It helps students engage with and think about new terms in several ways (see Figure 10.8).

- Acting out. Give each student one card with different instructions (e.g., “Open the window slowly”; “Carefully open your book”).

- Word sort. Students sort a series of words into various categories; later, they discuss their answers and the categories.

- Focus on cognates. This is an excellent way to build on and make connections to the preexisting knowledge that ELL students bring if their first language shares cognates with English. It also helps other students recognize the value of speaking other languages. See Figure 10.9 for an example.

Figure 10.8 Example of a word map.

| Words for star | Languages | |

|

str star aster Stern ster stea stjerne setare estrella estrela estêre |

Sanskrit Sinhala Greek German Dutch and Afrikaans Romanian Norwegian Persian Spanish Portuguese Kurdish |

Figure 10.9 Cognates for the word star.

- Vocabulary guides. This strategy is effective when using grade-level materials that are inaccessible to readers because they contain too many unfamiliar words. Guides can have definitions of the difficult terms or synonyms.

- Key word method. This mnemonic strategy uses a key word that can be associated with the target word based on meaning and sound and helps students recall the term.

- Target word: carline Meaning: witch

- Teacher identifies the word car (easy to represent visually and it sounds like the first part of the target word). Teacher shows a picture of a witch sitting in a car.

- When asked to recall the definition of carline, students follow a four-step process:

- Think back to the key word: car

- Think of the picture: a car

- Remember what else was in the picture: a witch was in the car

- Produce the definition: witch. (Mastropieri & Scruggs, 1998)

Sentence Level Features

Some grammatical features are especially troublesome for ELLs. Some are learned through usage, practice, and feedback, but others take longer and require a deliberate and explicit instructional approach. Although all teachers need to provide opportunities for ELLs to work on sentence level structures, the English language arts classroom is a prime setting for understanding and using correct grammar structures.

Students learning English as a second, third, or fourth language may encounter a variety of challenges as they try to apply the linguistic knowledge from their first language to English. This process is called language transfer. For example, students who speak a Slavic language (e.g., Russian, Croatian, Polish) have difficulty understanding the term article in English (when it is used to refer to the and a/an) because it does not have a direct translation in Slavic languages.

STOP AND DO

A useful guide on language transfer issues for students speaking Spanish, Vietnamese, Russian, Korean, Arabic, Tagalog, Khmer, Cantonese, Hmong, and Haitian Creole is Teacher’s Resource Guide of Language Transfer Issues for English Language Learners (2004), published by Rigby at https://schd.ws/hosted_files/onebyone2017/7a/Rigby%20Language%20Transfer%20Guide.pdf. Find information on students you have or expect to have in your school, and share that information with classmates.

In 2003, Robin Scarcella identified 10 major areas of focus for grammar instruction for ELLs: sentences, subject–verb agreement, verb tense, verb phrases, plurals, auxiliaries, articles, word forms, fixed expressions and idioms, and word choice. Figure 10.10 provides a list of these 10 areas with definitions and examples.

| Grammatical Features | Example | Incorrect Use |

| 1. Sentence structure

All sentences have one subject and one main verb. |

My tutor was the only one who helped me. | My tutor only one to help me. |

| 2. Subject–verb agreement

Subjects must agree with verbs in number (the s rule). |

They come from China.

He comes from Kenya. |

He come from Kenya. |

| 3. Verb tense

The present tense is used to refer to events that happen now and to indicate general truth. The past tense is used to refer to events that happened before now. |

My teacher explained how important recycling is for our planet. | My teacher explains how important recycling was for our planet. |

| 4. Verb phrases

Some verbs are followed by to + base verb. Other verbs are followed by a verb ending in -ing. |

My teachers convinced me to read many books | My teacher convinced me read many books |

| 5. Plurals

A plural count noun (e.g., dog, plant) ends in an s. |

She has two dogs. | She has two dog. |

| 6. Auxiliaries

Negative sentences are formed by placing do/did + not in front of a base verb. |

Do not cut the trees. | Not cuts the trees. |

| 7. Articles

Definite articles generally precede specific nouns that are modified by adjectives. |

I speak the Japanese language. | I speak Japanese language. |

| 8. Word forms

The correct part of speech should be used—nouns for nouns, verbs for verbs. |

We have confidence in our new president. | We have confident in our new president. |

| 9. Fixed expressions and idioms

Idioms and fixed expressions cannot be changed in any way. They are treated as a whole. |

You need to get your ducks in a row. | You need to get your chickens in a row. |

| 10. Word choice

Formal and informal words should be used in formal and informal settings or contexts, respectively. |

Dear Dr. Thorne | Hi Dr. Thorne |

Figure 10.10 Ten grammatical features that English language learners need to know.

STOP AND DO

Idioms are phrases in which the words together have a meaning that is different from the dictionary definions of the individual words. Idiomatic expressions are hard for ELLs to understand. Examples of idioms include “Break a leg,” “as good as new,” and, “it’s raining cats and dogs.” For a list of over 3,000 English idiomatic expressions, see UsingEnglish.com at http://www.usingenglish.com/reference/idioms/.

Select several local or online newspaper headlines. Paste them on a poster board and assign each a number. Identify the figure of speech in each line by number and explain in concrete terms what the line is saying. Here are some examples:

- “Updike’s way with words extended to baseball.”

- “Injured Duran ready to climb right back on that beam.”

- “AT&T’s earnings take a hit in fourth quarter.”

- “Celebrity parties going head-to-head at Super Bowl.”

- I am confused about. . . .

- What do you think this . . . means?

- This part . . . does not make sense to me.

- What caused . . . ?

- I wonder how did . . . ?

- What would happen if . . . ?

- My favorite part so far is . . . .

- This is confusing because . . . .

- This is hard because . . . .

- This is similar to . . . .

- This reminds me of . . . .

- The problem here is like . . . because . . . .

- I see your point, but I . . . .

- My idea/position/answer is a little different because . . . .

- I got a different result than you.

- I think . . . because . . . .

- In my opinion . . . .

- It seems that . . . .

- I guess that . . . .

- I anticipate . . . .

- I’m expecting . . . to happen because it says . . . .

- May I help you . . . ?

- It looks like you might need some help.

- Maybe we could . . . .

- Another way to say it is . . . .

- In other words, . . . .

- I hear you say . . . .

- Perhaps if you . . . .

- Have you considered . . . ?

- Another idea would be to . . . instead.

- Multiliteracies. Think about the diverse types of texts and writings you or your students are exposed to in one day. How is written language used within the school setting? Outside the school? For example, if a student takes the school bus in the morning, then walks to her piano lesson, and later attends her brother’s basketball game, what kinds of literacy practices does she encounter throughout the day?

- Language functions in one hour. Reflect on one recent lesson you taught or in which you participated as a student. Think about the number of language functions (that is, what students were asked to do with language) used during that one lesson. How might you teach an ELL how to use language functions appropriately?

- Teaching vocabulary. Select a book that you like from Vocabulary.com (http://www.vocabulary.com//index.php?dir=general&file=books) or another website and locate the list of vocabulary words for that book. Plan how to teach these vocabulary words using two or more of the strategies for teaching vocabulary discussed in Chapter 10.

- Writing and grammatical features. Analyze selected ELL student writing samples. What evidence do you find of a lack of familiarity with grammatical structures (see Figure 10.10) that might be different from errors made by native English speakers? How could you, as a teacher, help ELLs learn these usages and features?

- Review the following online resources for discussions on multiliteracies and new literacies.

- Coiro, J., Kiili, C. & Casek, J. (2017). Remixing multiliteracies: Theory and practice from New London to new times. NY: Teachers College Press.

- Cazden, C., Cope, B., Fairclough, N., & Gee, J. (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review, 66, 60–92. Retrieved from http://vassarliteracy.pbworks.com/f/Pedagogy+of+Multiliteracies_New+London+Group.pdf

- Leu, D. J., Forzani, E., Rhoads, C., Maykel, C., Kennedy, C., & Timbrell, N. (2015). The new literacies of online research and comprehension: Rethinking the reading achievement gap. Reading Research Quarterly, 50(1), 37–59. Available at: http://www.edweek.org/media/leu%20online%20reading%20study.pdf.pdf

- Munger, K.A. (2016). Steps to success: Crossing the bridge between literacy research and practice. Geneseo, NY: Open SUNY Textbooks. Retrieved from: http://textbooks.opensuny.org/steps-to-success/

- Villagómez, A., Wenger, K., & Ernst-Slavit, G. Blogging the way to understanding: Constructing meaning through reflection and interaction. In L. de Oliveira, M. Klassen & M. Maune (Eds.). Common Core State Standards in Language Arts, Grades 6-12 (pp. 95-110). Alexandria, VA: TESOL Press.

- Explore lessons. See Gottlieb, M. & Ernst-Slavit, G. (Eds.), (2013, 2014). Academic language in diverse classrooms: Promoting content and language learning English language arts. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin/SAGE Retrieved from https://us.corwin.com/en-us/nam/author/gisela-ernst-slavit. Examine the examples of complete ELA units of instruction in diverse classrooms with large numbers of ELLs (see the chapters listed below). Each chapter shows how teachers designed, implemented, and differentiated instruction for English learners for one unit of instruction. Each chapter also shows how the teacher integrated sets of standards such as the CCSS and English language development standards. Discuss what you see in light of what you read in this chapter.

Explain how you might use a task like this with your students.

Language Functions

In everyday conversations, language functions rely primarily on narratives. However, in the English language arts classroom, students are routinely asked to express disagreement, offer opinions, report a partner’s perspective, or predict what will happen next. For students to participate in this kind of academic talk, they need to learn and practice these specific language functions. The use of sentence starters or stems provides students with a starting point for constructing syntactically well-formed sentences. Figure 10.11 includes examples of sentence starters to scaffold conversations. Having this information on a poster or handout allows students to engage in meaningful discussion while practicing a variety of language functions.

| Selected Language Functions | Sentence Starters |

| Ask for clarification |

|

| Asking questions |

|

| Commenting |

|

| Connecting |

|

| Disagreeing |

|

| Expressing an opinion |

|

| Predicting |

|

| Offering assistance |

|

| Paraphrasing |

|

| Suggesting |

|

Figure 10.11 Sentence starters for scaffolding conversations.

Discourse Level Features

The English language arts classroom uses a variety of genres, as depicted in Figure 10.12. ELLs may not be familiar with some of these discourse forms or may not feel comfortable preparing a poetic response or a critique because these language forms might not be seen as academic in their countries and cultures. This suggests the need to clearly define and review expectations for each genre.

| autobiography ballad biography blog caption critique |

editorial expository essay monologue narrative newspaper article persuasive essay |

poetic response digital presentation script sonnet response logs webpage |

Figure 10.12 Types of discourse in the English language arts classroom.

Conclusion

The English language arts classroom is an ideal place for ELLs to learn many of the much- needed features of academic language. However, a heavy emphasis on form might not render the best results. ELLs (indeed all students) need to be able to connect what they are learning with what they already know and to build on their linguistic and cultural resources. In that sense, thinking about multiple literacies and not just one provides students the much-needed comfort and strength to add additional literacies. Finally, literacy instruction is enhanced if it is meaningful to the students, is done explicitly and systematically, and considers increasingly diverse oral, written, and technology-based practices.

Extensions

For Reflection

For Action

| Vol. | Authors | Grade Level | Content Topic |

| 1 | Grabriela Cardenas Olivia Lozano Barbara Jones |

K | Reading and Oral Language Development: My Family and Community |

| Eugenia Flores-Mora | 1 | Using Informational Texts and Writing Across the Curriculum | |

| Sandra Mercuri Alma D. Rodriguez |

2 | Developing Academic Language Through Ecosystems | |

| 2 | Terrel A. Young Nancy L. Hadaway |

3 | Informational and Narrative Texts: Our Changing Environment |

| Penny Silvers Mary Shorey Patricia Eliopoulis Heather Akiyoshi |

4 | Biographies, Civil Rights, and the Southeast Region | |

| Mary Lou McCloskey Linda New Levine |

5 | Literature and Ocean Ecology | |

| 3 | Emily Y. Lam Marylin Low Ruta’ Tauliili-Mahuka |

6 | Argumentation: Legends and Life |

| DarinaWalsh Diane Staehr Fenner |

7 | Research to Build and Present Knowledge | |

| Liliana Minaya-Rowe | 8 | Gothic Literature: “The Cask of Amontillado” |

>References

Biancarosa, G., & Snow, C. (2006). Reading Next—A vision for action and research in middle and high school literacy (2nd ed.). Report prepared for the Carnegie Corporation of New York. Washington, DC: Alliance for Excellence Education.

Carle, E. (1969). The very hungry caterpillar. New York: Collins Publishers.

Cazden, C., Cope, B., Fairclough, N., & Gee, J. (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review, 66, 60–92. Retrieved from http://vassarliteracy.pbworks.com/f/Pedagogy+of+Multiliteracies_New+London+Group.pdf

Center of Applied Special Technology. (2011). Universal design for learning guidelines, version 2.0. Wakefield, MA: Author.

Cervetti, G., Damico, J., & Pearson, P.D. (2006) Multiple literacies, new literacies, and teacher education, Theory Into Practice, 45(4), 378-386. doi: 10.1207/s15430421tip4504_12

Coiro, J., & Dobler, E. (2007). Exploring the online reading comprehension strategies used by sixth-grade skilled readers to search for and locate information on the Internet. Reading Research Quarterly, 42(2), 214 – 257. doi: 10.1598/RRQ.42.2.2

Coiro, J., Kiili, C. & Casek, J. (2017). Remixing multiliteracies: Theory and practice from New London to new times. NY: Teachers College press.

Coiro, J., Knobel, M., Lankshear, C. & Leu, D. (Eds.) (2008). Handbook of research on new literacies. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Common Core State Standards Initiative (CCSS) (2010). Common Core State Standards for English Language Arts & Literacy in History/Social Studies, Science, and Technical Subjects. National Governors Association Center for Best Practices, Council of Chief State School Officers, Washington D.C.

Cope, B., & Kalantzis, M. (2000). Multiliteracies: Literacy learning and the design of social futures. London: Routledge.

Fisher, D., Rothenberg, C., & Frey, N. (2007). Language learners in the English classroom. Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Gottlieb, M., & Ernst-Slavit, G. (2014). Academic language in diverse classrooms: Definitions and contexts. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Graham, S., & Perin, D. (2007). Writing next: Effective strategies to improve writing of adolescents in middle and high schools: A report to Carnegie Corporation of New York. Washington, DC: Alliance for Excellent Education.

Halliday, M. A. K. (1978). Language as social semiotic: The social interpretation of language and meaning. London: Edward Arnold.

Jewitt, C., & Kress, G. (Eds.). (2003). Multimodal Literacy. New York: Peter Lang.

Leu, D.J., Forzani, E., Rhoads, C., Maykel, C., Kennedy, C., & Timbrell, N. (2015). The new literacies of online research and comprehension: Rethinking the reading achievement gap. Reading Research Quarterly, 50(1), 1-23. doi: 10.1002/rrq.85.

Mastropieri, M. A., & Scruggs, T. E. (1998). Enhancing school success with mnemonic strategies. Intervention in School and Clinic, 33(4), 201–208. https://doi.org/10.1177/105345129803300402

Morrison, T. (1987). Beloved. New York: Alfred Knopf.

Munger, K.A. (2016). Steps to success: Crossing the bridge between literacy research and practice. Geneseo, NY: Open SUNY Textbooks. Retrieved from: http://textbooks.opensuny.org/steps-to-success/

National Coalition for Core Arts Standards (2014). National Core Arts Standards. State Education Agency Directors of Arts Education. Dover, DE. Retrieved from www.nationalartsstandards.org

National Council of Teachers of English/International Reading Association. (2012). Standards for the English language arts. Urbana, IL: NCTE Publications. Retrieved from http://www.ncte.org/standards

Paulsen, G. (1999). Hatchet. New York: Aladdin Paperbacks.

Scarcella, R. (2003). Accelerating academic English: A focus on English language learners. Oakland, CA: Regents of the University of California.

Snow, C. (2005). From literacy to learning: Catherine Snow on vocabulary, comprehension, and the achievement gap. Harvard Education Letter, July/August. Retrieved from http://www.edletter.org/current/snow.shtml

Twain, M. (1987). The wit and wisdom of Mark Twain. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications.

Villagómez, A., Wenger, K., & Ernst-Slavit, G. (2015). Blogging the way to understanding: Constructing meaning through reflection and interaction. In L. de Oliveira, M. Klassen & M. Maune (Eds.). Common Core State Standards in Language Arts, Grades 6-12 (pp. 95-110). Alexandria, VA: TESOL Press.