12 Chapter 9 Supporting Teacher Development

The International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE), in addition to developing the widely used national education technology standards for students (NETS*S), has also developed a set of standards for teachers, called NETS*T, which focus on pre-service teacher education (available at https://www.iste.org/standards/standards/for-educators), and they also provide guidelines for teachers who are still learning about technology. The NETS*T recommend that teachers function as learners, leaders, citizens, collaborators, designers, facilitators, and analysts as they support the student standards in their classrooms. Part of what these standards require is that teachers understand and can use technology to work toward student creativity, production, critical thinking, and other learning goals. In other words, teachers are charged with not only learning the technical aspects of technology, but also practicing how to meet learning goals and discovering the technology that allows and enhances such opportunities. Rubrics, lessons, and other resources that can help teachers to measure and use the standards can be found at http://www.iste.org/standards/standards. It should be noted that, although many states and districts use the ISTE standards, they are themselves not law. However, there is a federal requirement, presented in the reauthorized Elementary and Secondary Education Act (2015), for states to meet these goals:

Improving student academic achievement through the use of technology

Assisting students in becoming technologically literate by the time they finish eighth grade

Ensuring that teachers can integrate technology into the curriculum.

In whatever way states choose to make sure these goals are met, whether by adopting the NETS*T or developing their own standards, teachers no longer have a choice about using technology in their instruction. How well they do so may depend on large part on the effectiveness of their professional development experiences in technology-supported learning.

OVERVIEW OF PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT IN TECHNOLOGY-SUPPORTED LEARNING

What Is Professional Development?

Professional development (PD) is an opportunity that leads to an increase or change in skills, knowledge, abilities, and understandings. These changes can occur through any number of means. PD experiences include individual study, action research, in-service workshops, online graduate courses, internships, temporary residencies in organizations, curriculum writing, peer collaboration, school or district study groups, peer coaching or mentoring, or work with a mentor or master. Most states or districts require teachers to participate in specific amounts of some kind of PD to keep their teaching certification current or to meet the requirements of their Professional Improvement Plans, and it’s a good idea for pre-service teachers to keep this in mind as they plan their first years of teaching. However, the outcomes of PD typically are not measured in any substantive way, the thought being that any PD is effective in helping teachers to teach well.

Unfortunately, not all PD opportunities are the same, and certainly not all are useful. While investing in staff development and supporting good teaching are the best ways for schools to make sure that technology use leads to student achievement, PD experiences cannot simply consist of learning new techniques to apply “tomorrow.” Rather, PD must help teachers to “transform their role” by understanding current educational issues, implementing innovations, and improving their overall practice (Wood, Goonight, Bethune, et al, 2016). In other words, the purpose of PD is not for teachers to teach better in traditional ways, but to learn better and different ways to teach. Both incremental and fundamental changes are important to the change process. However, teacher changes and related changes to the education system are complex and dynamic and cannot happen through short-term, one-shot opportunities for professional development.

Teacher Uses of Technology

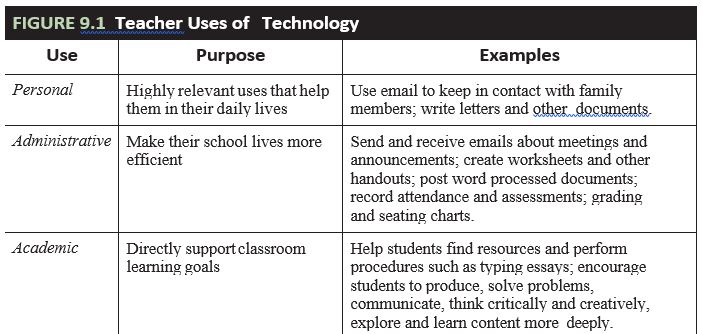

Key to understanding the issues of professional development in technology-supported learning is understanding teachers’ uses of and attitudes toward technology. In general, there are three categories into which teacher technology use falls: personal, administrative/productivity, and academic. Figure 9.1 outlines these three uses.

All of these technology uses are important in the development of competent technology- using teachers. Most important for professional development is that teachers see that PD is linked to their immediate needs and interests.

The Need for Professional Development Opportunities in Technology

After a single pre-service teacher education technology course, many practicing teachers discover that they are unprepared for the realities of teaching and using technology to transform their classrooms and schools. In addition, few teachers emerge from their teacher education programs equally competent in each of the three categories of technology use mentioned previously. Although teachers often seek out and take advantage of chances to learn about technology for personal and administrative uses, typically fewer informal opportunities to learn about academic uses are available.

New learning standards in all areas and the need to develop better ways to assess students are pushing teachers to change their roles in classrooms and schools. Many teachers feel the stress of trying to keep up with academic uses of technology, of meeting new and changing standards for both students and teachers, and of working to help all their students succeed. Separately these are daunting tasks; together they may constitute an over- whelming burden, especially when teachers see that these goals may change in unpredictable ways at any time. However, effective professional development opportunities can support teachers in reaching these goals and lead to change in the system itself.

Characteristics of Effective Professional Development in Technology-Supported Learning

The traditional model for professional development is a deficit model of learning in which teacher-students are expected to learn from listening to experts. In the same way that education is trying to move away from this model for students, we must employ a more teacher-centered growth model for PD. Effective PD tasks:

Consider the needs and learning styles of teachers.

Present information in authentic contexts with direct links to classrooms and provide feed- back while teachers try new strategies in their classrooms.

Allow time for reflection and experience.

Are social and active in nature, allowing teachers to interact and collaborate with colleagues and mentors.

Present ways to get from A to B, not just new ideas that require an instant and complete transformation.

Focus on tools that teachers use for their own productivity.

Present information in a variety of formats.

Are made at the teacher’s level. Teachers are more likely to use information that is for their grade and content than that which they have to adapt or revise to use.

Continue over time.

(Darling-Hammond, Hyler, & Gardner, 2017; Feiman-Nemser & Remillard, 1995; Lowenberg Ball & Cohen, 2000; Wells, 2007)

The most important aspect of PD tasks is that they result in improved student learning and performance over time.

Benefits of Professional Development in Technology-Supported Learning

PD that follows the guidelines for effectiveness noted above can lead to a number of important teacher, classroom, and school changes. As most authors note, professional development of teachers is central to school change. In fact, research shows that teacher quality is the most important variable in student learning (see, for example, Bird, 2017). Teacher improvement can lead to higher student achievement and to systemic changes in schools. In addition, teachers can be refreshed and reenergized by working with peers, solving classroom problems, and learning more effective ways to support the learning of all students.

THE TECHNOLOGY PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT PROCESS

PD is essentially an individual enterprise because growth first takes place in individual teachers. Coughlin and Lemke (1999) and other more recent literature propose an iterative, or repetitive, growth process that teachers generally go through during effective technology PD:

Entry: Teachers do not yet have the skills and knowledge to change their practice. During this stage they

Build knowledge.

Understand possible changes.

Adaptation: Teachers use technology to support existing practice rather than to change the classroom. At this stage they

Apply (try new ideas and understandings, assess their effectiveness, adapt and change as needed, try again).

Revise their practice.

Repeat.

Transformation: Teachers use technology to help them change their practice in important ways. During transformation they

Share with colleagues.

Document successes and failures.

Evaluate the changes in both the environment and learner achievement.

Any stage can be revisited an unlimited number of times, or even skipped, as teachers work through their individual learning processes. Of course, learning and change are more complex than this simple process implies, but teachers can use this description to generally understand the process and their place in it.

Also important to succeeding in the PD process are these suggestions from enGauge (2004), which, although offered over a decade ago, are still relevant:

Stay focused on the goal of helping students.

Take on goals that are challenging but doable.

Convince others that technology and thinking skills can lead to higher student achievement.

Build on the good work that is already underway.

Collaborate to support a system-wide culture of innovation.

The PD process is similar to the independent learning processes that teachers must encourage their students to work toward. By experiencing it for themselves, teachers may be better able to support this process for their students.

Challenges for Teachers in Technology Professional Development

There can be many challenges for teachers who want to participate in PD and for those who want to work toward change based on their PD experiences. However, for each barrier there are a variety of possible solutions.

Time

Sometimes teachers are unaware of technologies that can make their classrooms contexts more effective and efficient learning environments; sometimes, when they do know, the belief that learning to use these technologies will take longer than it is worth stops them from trying. According to Hubbard (2017) and others, time is the most crucial barrier to teacher development. This may be in part because teachers and others in the educational community see PD as something that individual teachers have to set aside large chunks of time for. But Cook and Fine state that for PD to be effective it must become “part of the daily work life of educators.” In other words, time must be made by schools and districts and a community culture developed that not only allows ongoing learning but supports it as much as possible. Across the literature, educators suggest some useful and effective ways to provide the time necessary for sustained PD experiences; these include:

Restructuring the school calendar.

Using permanent substitutes.

Scheduling common planning time.

Integrating PD into classroom time.

In the end, it may come down to a trade-off—spend time learning to then teach more efficiently and effectively.

Access

Teachers cannot use technology that they cannot get to at all, and some teachers cannot get to it as often or as well as they would like. Without access to technology teachers also cannot practice new skills. Examples throughout this book provide examples of how administrators, teachers, and other stakeholders can work together to make sure that teachers have the access they need. Many teachers who have not been able to secure access to school and district resources have obtained their own technology funding through grants available from a wide array of organizations. More on funding is presented in the Guidelines section of this chapter.

Knowledge

As previously noted, there are many sources of information for teacher PD in technology- supported learning. However, sometimes local resources are the most useful. For example,

Students. Often students have technical know-how that teachers do not and can provide instruction for their whole class. Bray (2011) proposes that schools develop student experts. These knowledgeable and/ or willing students can receive training before and after school for a specific amount of time and then obtain a special status and limited access to the school network. Their identifying badges let peers know whom they can call on for help and let the teacher know whom she can count on for on-the-spot instruction. YouTube videos, peers, online tutorials, and other resources are available to teach students how to use specific technologies.

Colleagues and other staff members. In-school staff may have a just-in-time answer that can save a frustrating wait for technical support people.

Teachers’ guides. Guides and tutorials that accompany and support software packages apps often focus on process and provide many additional relevant activities.

Local conferences, workshops, and in-services. Many school districts, professional organizations, and state education agencies offer workshops, seminars, and conferences that either focus on technology or have a technology strand. Typically cheaper and more personal than the large national conferences, these opportunities can offer a wealth of resources, data, and relationships with interested peers. The CUE conference in California and NCCE in the Pacific Northwest are excellent examples of outstanding regional conferences.

Parents, community volunteers, school library media specialists, and school technology coordinators can also be excellent sources of knowledge and support.

Working with parents

Communicating with parents, particularly helping them to understand technology use in schools, takes time and thought. Getting parents on board with technology PD can sometimes be a struggle. To make communication with parents easier, teachers can build on other teachers’ experience and download forms and letters from great sites like TeacherTools (www.teachertools.org/) or timesaversforteachers.com. Most school districts also have teacher Web pages and some kind of communication app to help teachers and parents communicate.

Working with ELL and special-needs children

In the past PD for content-area teachers did not often address the needs of all the student populations in a class; rather, issues of special needs and ELL children were addressed separately. However, with the current understandings of the effectiveness of differentiated instruction and the focus on inclusion, many more PD experiences deal with the success of all students. Clearly, teachers cannot make all of these changes themselves. Schools and communities need to support teacher PD and provide ways to meet these challenges.

GUIDELINES FOR WORKING TOWARD EFFECTIVE TECHNOLOGY PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT

Like student learning, effective teacher growth can only happen when the support and encouragement that teachers need is available. The guidelines in this section provide ideas about some ways for teachers to gain both support and encouragement and to have rewarding and effective PD experiences.

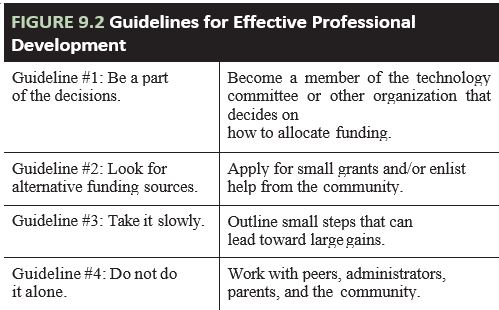

Guideline #1: Be a part of the decisions. Being on the school or district technology committee does take a commitment of time and effort. However, teachers who understand what it takes to effectively integrate technology into learning can help to make sure that technology funds pay for both the hardware and the training that is necessary.

Guideline #2: Explore alternative funding sources. Although experts recommend that 25–30% of technology budgets be devoted to professional development, it rarely is (Fletcher, 2005). In addition, millions of technology dollars each year are left sitting in organizational coffers, unclaimed by the teachers that they are meant to help. There are a variety of reasons for this, some dealing with teachers’ lack of time for grant writing and knowledge of resources, others with the misunderstanding that technology grants are hopelessly complicated to complete and win. Large grants, especially those from the federal government, typically require a lot of work and are not always successful, but they can offer years of support and extensive funding. Pairing with faculty at universities or local civic organizations who can help with grant preparation and administration can be effective for all participants.

In addition, there are a large number of foundations and other organizations working to fund teachers needing specific hardware such as handhelds (search “education technology grants”) or software in areas such as reading improvement. Even a small grant can provide impetus for PD and access to the technology that can make it happen. Further, many commercial software and hardware publishers offer their own grants of money and/or materials, and some

offer links and other information to help teachers. In many cases securing funding requires only a one-page description of the need; in others it is more involved, but resources exist across the Web to assist teachers in preparing grant documents.

Guideline #3: Take it slowly. As noted above, time is a crucial component in teacher professional development (Darling-Hammond, Hyler, & Gardner, 2017). Learning to use technology well does not happen quickly, but rather it is a process of learning, testing, revising, and evaluating. Just as students should not be expected to become critical or creative thinkers overnight, teachers should not be expected, or expect themselves, to become instant technology integration experts. It may be frustrating to take only small steps, but learning and change are slow processes, and in the end the small steps can add up to large gains.

Guideline #4: Do not do it alone. As other parts of this book have stressed, there are many education stakeholders, both direct and indirect, who can be called on to work with teachers and students. Stevenson’s (2004/2005) research showed that these kinds of informal collaborations can lead to effective technology integration in the classroom, and other studies have shown the importance of school and other technology partners to successful PD (cf. Ludwig & Taymans, 2005). To support teacher PD, parents can be asked to help in all kinds of ways. For example, they can participate in funding drives, be part of dissemination or reading groups with teachers, work with the results of PD by sharing and commenting on their children’s electronic portfolios, or make contact with teachers through tools like Skype. Peers at the same school and col- leagues throughout a district or across districts who have the same needs for PD can form working groups, and administrators can be invited to join to see the effect of the efforts. Even students can support teacher PD by being willing to try new ideas and tasks and to participate honestly and openly in their evaluation. Because learning is social and teachers are already isolated enough in their classrooms, PD should happen with the support and participation of others.

TEACHER TOOLS FOR TECHNOLOGY-SUPPORTED LEARNING

This chapter started by describing three categories of teacher technology use. This section addresses administrative tools for teachers for several reasons. First, personal uses of technology are just that—personal—and so cannot be prescribed. Most teachers will find and use the tools that they need for personal productivity. Second, academic uses of technology have been described already in every other chapter of this text. Finally, the effective use of administrative tools can free time for teachers to participate in PD experiences. Administrative tools include any that help teachers prepare for, carry out, and monitor instruction (versus academic tools, which are integrated into learning tasks). Many administrative tools have been mentioned in other chapters. These include Web site generators, rubric creators, and puzzle and other activity makers. Others are described here.

Administrative Tools for Teachers

Translators/parent letters. In addition to professional development opportunities, 4Teachers has links to administrative tools. Try Casa Notes to send home notes in Spanish (www.4teachers.org/) and Google Translate for other languages.

Clip art. For great free school clip art, see discoveryschool.com’s Clip Art Gallery.

Forms and handout templates. An amazing number of ready-made templates can be found at Education World’s Tools and Templates page (http://www.educationworld.com/tools_templates/index.shtml). Worksheet makers allow teachers to build their own worksheets using a variety of scaffolds or to use/adapt premade worksheets.

Screen timer. Computer-based timers that show up on the screen allow everyone in the classroom to see how much time is left, which is useful for students who need to pace themselves during tasks. They have a variety of settings for different contexts. Search “screen timer” to find one that works in your classroom.

Classroom management tools. Administrative tools from Scholastic.com (http://teacher.scholastic.com/tools/) include apps, calendar and book tools, and other planning help.

Lesson planner. These apps provide guidance for teachers to write complete, standards-based, content-focused lessons. They range from the PlanbookEdu app (https://www.planbookedu.com/) to free planner pages at http://www.playdoughtoplato.com/teacher-planner/.

There are other tools that can function both as administrative and academic support for teachers and help teachers work toward PD. These include resources such as:

Atomic Learning (www.atomiclearning.com/), Linda.com, TEDTalks. Teachers can search, view, and or subscribe to participate in multimedia tutorials or lecture of their choice or incorporate student tutorials into instruction.

Pinterest (pinterest.com). Truly the best source of all things classroom, from lists of great apps and classroom posters to lesson ideas and tutorials.

LEARNING ACTIVITIES: PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT

Whether teachers want to take it fast or slow, make incremental or fundamental changes, there are all kinds of activities to get them started. Right now, while waiting for funding, the district technology plan, more resources, or other support, teachers can take a step toward their larger goals and participate in any of these activities to make immediate changes in their instruction:

View sample elementary through high school activities from the Handbook of Engaged Learning Projects (HELP) (www-ed.fnal.gov/help/index.html).

Ask questions at teacher electronic discussion groups or join communities such as simpleK12 (http://www.simplek12.com/teacher-learning-community/).

Get inspired by cruising some of the coolest sites for kids on the Web. Definitely start at DiscoveryKIDS (discoverykids.com). Then visit www.iknowthat.com.

Set up a cooperative group with your colleagues at Yahoo.com, Google Groups, or another easy to access app. Use the system from home to share useful Web sites and other resources.

Create a literature circle for teachers and administrators within the district and work through one of the books on technology that the group has been meaning to read.

Take an inspirational virtual journey. Take a private museum tour through one of the 33,000 museums connected to http://museumnetwork.com. Be sure to check the MuseumEducator.org link to access teacher resources from museums across the United States.

Visit a new “world” – choose from among those recommended by Wheelock and Merrick (2015; https://www.iste.org/explore/articleDetail?articleid=395).

Subscribe to an online educational technology journal, magazine, or newsletter. Try From Now On (http://fno.org) for an easy and useful read or any of the newsletters from Education World. The free daily SmartBrief on EdTech is chock full of news, ideas, competitions, grant announcements and more (sign up at www.smartbrief.com).

Choose a relevant tutorial from i4c (www.internet4classrooms.com/on-line2.htm; Technology Tutorials for Teachers (eduscapes.com/tap/ topic76.htm), 2learn.ca (www.2learn.ca/teachertools/teachertools.html), or PBS Technology Tutorials (www.pbs.org/teachersource/teachtech/tutorials.shtm). Be sure to share when done.

Visit the Motivating Moments Web site at www.motivateus.com/teachers.htm for inspiration.

Read a book to obtain a different view of educational technology. Classics include:

Johnstone, B. (2003). Never mind the laptops: Kids, computers, and the transformation of learning. New York: iUniverse.

Cuban, L. (2002). Oversold and underused: Computers in the classroom. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bowers, C. (2000). Let them eat data. How computers affect education, cultural diversity, and the prospects of ecological sustainability. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press.

Ferneding, K. (2003). Questioning technology: Electronic technologies and educational reform. New York: Peter Lang.

Khine, M., & Fisher, D. (2003). Technology-rich learning environments: A future perspective. New Jersey: World Scientific Publishing.

There are many ways that teachers can jumpstart their PD—the activities listed above constitute only a small portion of them.

ASSESSING PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT

The ultimate goal of evaluating teacher technology PD is to determine whether professional development promotes using technology to improve student achievement. Assessment of PD can take many forms and involve many people, such as:

An evaluation team. Darling-Hammond, Hyler, and Gardner (2017) recommend that a team be created to ensure the quality of the professional development experience(s) and help perform both formative and summative analyses of the process. This team can consist of an administrator, a technology staff member, a content-area peer, and the teacher, or any combination of participants who are able to evaluate the experience.

Teacher self-assessments. Teachers can reflect both on the experience and on the long-term effects.

Student data. Achievement data in the form of test scores, grades, and student self-reflections can be collected over time to evaluate the impact of the changes.

Like planning classroom experiences, evaluation of PD experiences should be part of the process from the beginning. NCREL (2004) recommends the following evaluation process:

Clarify goals and assess their value.

Analyze the context.

Explore the PD program’s research base and evidence of effectiveness.

Determine multiple indicators for assessing goals and define who will gather what evidence when.

Collect and analyze evidence on participants’ reactions, learning, and use of new knowledge and skills. Also, look at evidence of organizational support and change and student outcomes.

Present the results to all stakeholders and suggest possible changes.

The results of these assessments can help teachers and others to choose effective PD experiences and to work toward technology integration in a purposeful way.

FROM THE CLASSROOM

Connections

When I attended [a conference] this year, the state PTA president gave a workshop around parent involvement. One example they gave was the use of classroom-produced videos. Some students have parents unable to read, unable to attend open house, etc., but most families now have a television and VCR. Videos were created by teacher and students (could get volunteers to do the recording) showing parents: students at work, classroom goals, suggestions for helping with homework. In other words, an overall picture of the child’s classroom. The response has been tremendous, and the payoff is that more parents want to come to the school. Another suggestion, which has been tried at our school, is the use of technology during staff meetings. PowerPoint presentations are made (the principal has tapped into the staff members with technology knowledge and skill), staff use the AlphaSmarts during staff meetings to look up info or type notes, videos are shown showing teachers (from our school) using examples of good teaching practices. (Jean, middle school teacher).

Barriers

Our school applied for a grant and received five computers for every sixth-grade classroom. We have had mostly problems. As teachers, we attended staff development, continued to learn on our own, have the students use the computers for drill-n-practice, to gather information. Unfortunately, as the computers crashed, the district did not provide technical support. We have had to pay for any maintenance and for additional wiring. In several of the sixth-grade classrooms, nonfunctioning computers sit on the floor because no one seems to want to fix them or take them away. Other schools have received fewer computers, but they were bought by the district and technical support is provided. This is a good example of where more information and asking questions should have happened before accepting the “free” computers. (Jean, middle school teacher)

The person in charge of choosing the software in our building is very well trained and knowledgeable about the software we purchase. The problem? Well, our tech coordinator is also our librarian. She is always swamped with questions and troubleshooting. The problem has become so huge, we now have a little basket where we fill out our questions/headaches, etc., and a district technician comes by about once a week to go over the “yellow slips.” (Andrea, elementary bilingual teacher)

Sharing

Accountability to the state is important, but what about to the students? If they are only being trained how to take a test that is not a fair representation of their knowledge, how are they learning the valuable skills of working collaboratively to solve complex and real-life problems? Perhaps you could start slowly, by adding a few authentic learning activities where students will be learning the discrete knowledge they need for the test, but can also have an opportunity to apply it in some manner—perhaps with technology. Your situation with computers that do not have Internet access or word processing programs is quite eye-opening! It sounds as if you are in need of at least one decent computer with a basic software program to start with. If that isn’t available, there are other forms of technology that some parents in the community might be willing to loan the classroom for a day or two: video cameras, laptops, digital cameras, tape recorders, typewriters, etc. And once you can get a few of these technologies, you can begin to help your students meet the NETS standards for students. Now, it sounds as if you aren’t very comfortable with teaching students how to use these technologies. No fear! I’ve known many teachers who use various strategies to get around this barrier. First, begin with what you do know and teach a few select students. Those students can then become experts and share their “knowledge” with others in the class.

Perhaps there are older students in the school or high school who would be willing to volunteer an hour or two every week and do the same. I think you’ll be surprised with the wealth of knowledge available to you in the form of your students in your own district. To help your students become independent users of the technology to save you time for teaching and instruction, you can make a list of various skills and knowledge and have student experts sign their names under each that they qualify for, so that the class will know where to go when they encounter a question or problem. Also, as you have various groups of students coming and going throughout the day, it might be helpful to open up your classroom during recess once a month or so and train a few of your experts. While these are only suggestions, I want to encourage you not to give up on technology but to continue making baby steps with what you can do and do have available to you by using a few creative strategies to overcome the barriers you encounter. (Jennie, elementary teacher)

CHAPTER REVIEW

Key Points

Understand the role of professional development in technology-supported learning in student achievement and school change.

Teacher quality is the most important variable in student learning. Although many factors determine how teachers think and act, it is clear that they hold the key to student achievement.

Discuss guidelines for professional development in technology-supported learning.

A thoughtful, reflective approach to PD will help teachers get the most out of each experience. Working with peers and other stakeholders and being part of the decisions, whether on funding, class size, or technology purchases, can also make a difference.

Evaluate tools for teacher development in technology-supported learning.

An amazing array of tools exists for teachers’ personal, administrative, and academic uses.

Discover and participate in effective activities to support technical and pedagogical development.

Teachers must develop their understandings about learning and about technology. Even activities as simple as reading an article or playing with a new tool can play a role in teacher learning.

Assess your own development in technology-supported learning and teaching. Although multipoint, multi-evaluator assessment provides a clearer overall picture of PD experiences, teachers can use many of the self-assessment tools found in books and on the Web to reflect on their own changes and on changes to their classrooms and schools.

REFERENCES

Bird, D. (2017). Relationship between teacher effectiveness and student achievement: An investigation of teacher quality. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. Available through: https://search.proquest.com/openview/1fabfc0a1479515498b91473259979bb/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y

Bray, B. (2011). Who are the experts now? Rethinkinglearning. Available: http://barbarabray.net/2011/10/21/who-are-the-experts-now/.

Cattani, D. (2002). A classroom of her own: How new teachers develop instructional, professional, and cultural competence. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Cook, C., & Fine, C. (1997a). Critical issue: Evaluating professional growth and development. Oak Brook, IL: North Central Regional Education Laboratory. Available: http://www.ncrel.org/sdrs/areas/issues/educatrs/profdevl/pd500.htm.

Cook, C., & Fine, C. (1997b). Critical issue: Finding time for professional development. Oak Brook, IL: North Central Regional Education Laboratory. Available: http://www.ncrel.org/sdrs/areas/issues/educatrs/profdevl/pd300.htm.

Coughlin, E., & Lemke, C. (1999). Professional competency continuum: Professional skills for the digital age classroom. Santa Monica, CA: Milken Family Foundation. Available www.mff.org/publications/ publications.taf?

Darling-Hammon, L, Hyler, M., & Gardner,M. (2017, June 5). Effective teacher professional development. Learning Policy Institute. Available: https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/effective-teacher-professional-development-report

enGauge. (2004). 21st century skills: Getting there from here. Available: http://www.ncrel.org/ engauge/skills/there.htm.

Feiman-Nemser, S., & Remillard, J. (1995). Perspectives on learning to teach (Issue Paper 95-3). East Lansing: Michigan State University.

Fletcher, G. (2005, June). Why aren’t dollars following need? T.H.E. Journal, 32(11), 4.

ISTE NETS Project (2005). National Educational Technology Standards. Available: cnets.ste.org.

Hubbard, P. Technology and professional development. TESOL Encyclopedia of English Language Teaching. Alexandria, VA. TESOL. 1-7.

Kanaya, T., Light, D., & McMillan-Culp, K. (2005, Spring). Factors influencing outcomes from a technology-focused professional development program. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 37(3), 313–329.

Loschert, K. (2003, April). Are you ready? NEA Today. Available: http://www.nea.org/neatoday/ 0304/cover.html.

Lowenberg Ball, D., & Cohen, D. (2000). Developing practice, developing practitioners: Toward a practice-based theory of professional education (chap 1). In L. Darling-Hammond and G. Sykes (Eds.), Teaching as a learning profession: Handbook of policy and practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Ludwig, M., & Taymans, J. (2005). Teaming: Constructing high-quality faculty development in a PT3 project. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 13(3), 357–372.

NCREL (2004). Guidelines for evaluating professional development. Pathways Home. North Central Regional Educational Laboratory. Available: http://www.ncrel.org/sdrs/areas/issues/methods/technlgy/te91k17.htm.

NCTRL (1993). Findings on learning to teach. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University.

Peterson, S. (1999). Teachers and technology: Understanding the teacher’s perspective of technology. San Francisco: International Scholars Publications.

Piexotto, K., & Pager, J. (1998, June). High quality professional development: Finding time for pro- fessional development. By request. Available: http://www.nwrel.org/request/june98/article8.html.

Rodriguez, G., & Knuth, R. (2000). Critical issue: Providing professional development for effective technology use. Oak Brook, IL: North Center Regional Educational Laboratory. Available:

http://www.ncrel.org/sdrs/areas/issues/methods/technlgy/te1000.htm.

Stevenson, H. (2004/2005, Winter). Teachers’ informal collaboration regarding technology. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 37(2), 129–144.

Wells, J. (2007, January). Key design factors in durable instructional technology professional development. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 15(1), 101–122

Wood, C., Goodnight, C., Bethune, K, Preston, A., Cleaver, S. (2016). Role of professional development and multi-level coaching in promoting evidence-based practice in education. Learning Disabilities, 14(2), 159-170.

Feedback/Errata