9 Chapter 7 Supporting Student Production

Production is mentioned in the standards in every content area and also in the national standards for English language learners. Words like “compose,” “design,” “create,” “model,” “develop,”, and “report” are used to indicate that an important aspect of student learning across the content areas involves student products such as musical scores, written descriptions, models, multimedia presentations, posters, and role-plays. In science and social studies, as in math, music, and English, teachers and students are expected to use the production process to learn. Production projects also meet many of the other standards because they involve understanding, communicating, collaborating, and other learning goals.

OVERVIEW OF TECHNOLOGY-SUPPORTED PRODUCTION IN K–12 CLASSROOMS

In order to support production effectively, teachers must understand why production is important and how it occurs.

What Is Production?

Production is a form of learning whereby students create a product or a concrete artifact that is the focus of learning. Production is one kind of project-based learning; production can be seen as the process, and the product is typically the end result. There are many kinds of tasks used in classrooms, but not all of them result in a tangible product. For example, some tasks lead to new understandings, a discussion, or an action. In production projects, both the impetus and outcome of learning are a material object. In other words, a tangible, manipulable outcome is the driving force behind the development of each stage of the production project.

Products can take many forms, for example, a slide show, photographs, three-dimensional objects, or a portfolio (discussed further in chapter 8). They can range from essays to multimedia presentations to more elaborate productions. Good products are the result of communication, collaboration, creativity, and other student goals discussed in this book. Production is also a valuable activity in itself, particularly if the products are based in curriculum standards and support language and content learning.

Because it is a relatively new teaching strategy for many classrooms and contains many elements of other strategies, and because it is hard to measure, research on production continues to develop. However, the theoretical support for project-based learning goes back to Dewey’s idea (1938) of learning by doing, and the components of production have received a great deal of attention in the literature. Learning goals that can be included in the production process are widely supported in the literature as leading to gains in student achievement; for example, collaboration (discussed in chapter 3), problem solving (chapter 6), and critical thinking (chapter 4). In addition, active learning, or learning activities in which students do and think about what they do, has been found to be more useful for students than inert knowledge transfer (i.e., lecture). Active learning is more likely to be remembered and applied (Adams & Ray, 2016). In addition, as noted in several other chapters in this text, the literature shows that achievement will be greater if educational tasks and contexts are similar to real-life tasks and contexts. This means that authentic activities that are meaningful in students’ lives support student achievement.

Overall, research exploring the use of project-based learning shows that students gain in subject matter, in skills and strategies worked on as part of the project, in problem-solving with groups and other work behaviors, and in attendance and attitude (George Lucas Foundation, 2005; San Mateo County Office of Education, 2001; Thomas, 2000). More important for some stakeholders in the educational process, some evaluations of project-based learning show student gains of more than 10% on statewide skills assessments (San Mateo County Office of Education, 2001).

Characteristics of effective production tasks

There is no one accepted model of project-based learning. In fact, it is implemented in so many different ways in classrooms that the distinctions between it and other learning activities are often blurred. The results of production activities can span the range from highly structured and prescribed outcomes, such as a written dialog with five lines that must contain certain vocabulary and grammatical items, to a very loosely controlled outcome, such as some type of new invention. During highly structured projects, students are provided with a clearly defined outcome, which they attempt to reproduce to the teacher’s specifications; in loosely controlled projects, students are given a general area in which to produce and have many choices in the forms and features of their products.

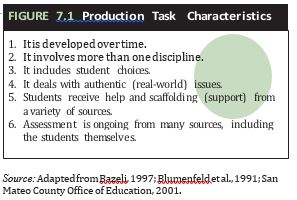

The flexibility involved in creating production tasks means that teachers with different philosophies of teaching and learning can take advantage of production as a strategy. In the educational literature on production, characteristics of an effective production task generally include those in Figure 7.1

Student benefits of production

Production can serve as a motivator by engaging students in the process of their learning. Production also allows students some leeway to work in ways that they prefer, helps them to develop real-world skills, and develops their abilities to communicate and collaborate with others. Most important for production projects, students are motivated by producing a tangible outcome. Like other types of group projects, well-planned production projects can result in the following student gains:

Individual and group/social responsibility

Planning, critical thinking, reasoning, and creativity

Strong communication skills, both for interpersonal and presentation needs

Cross-cultural understanding

Visualizing and decision making

Knowing how and when to use technology and choosing the most appropriate tool for the task (George Lucas Foundation, 2005)

Production projects can also benefit a wide range of students. For example, these projects can support the skills and abilities of English language learners. Production offers all students opportunities to communicate in a variety of modes (e.g., speaking, drawing, gesturing), to receive language and content input in a variety of modes (e.g., graphics, video, listening), and to use different learning styles (e.g., hands-on, visual, aural) during the production process. This helps ELLs to receive input in English that is comprehensible, to work in ways that they understand, and to play a role in the project regardless of their language fluency. Many benefits of project-based learning can be found in the Buck Institute for Education’s 2013 document “Research Summary: PBL and 21st Century Competencies” at https://www.bie.org/object/document/research_summary_on_the_benefits_of_pbl.

In addition, the variety of tasks that are part of the production process, described in the following section, makes it easier to integrate students with different physical, social, and psychological abilities. Students can play roles that most suit their needs and aptitudes.

THE PRODUCTION PROCESS

What Is the Production Process?

Producing facilitates learning in many ways, but creating a product is not enough to promote effective learning. The production process is crucial to learning as students work to understand and make decisions about the product. During a production project, the three main stages are planning, development, and evaluation. These stages are similar to those used in other learning activities, but the focus here is on a product.

The preproduction stage

In the preproduction or planning stage, students may help the teacher to uncover the features of a good product and develop rubrics and other evaluations to guide both process and product. Students construct a schematic that lays out in different ways the various steps in the project. They then conduct initial research, include finding information from print and electronic sources and evaluating existing products (if any). Students can also conduct interviews and plan other interactions with their intended audience. Students brainstorm, draw, discuss, demonstrate, and create a draft plan that includes roles for team members, tools needed, and a plausible timeline for each step. They use feedback from the teacher and other stakeholders to revise their plans as necessary.

The production stage

During the production or development stage, students engage in direct creation, including designing, making models of their products, and performing the other tasks outlined in their plan. Teams use feedback from audience members and other stakeholders and the rubric criteria to form their product.

The postproduction stage

During postproduction, or the evaluation stage, students reflect on feedback from their audience and on the process and product. They debrief, or discuss and reflect, individually, in teams, or as a class. The production process is not linear; rather, it is iterative in that students can repeat previous stages at any time as needed. In other words, if they find that they need to do additional planning or re-planning during the production stage, they can do so.

Teachers and Production

The teacher’s role in production projects

The teacher plays a crucial role in the success of production projects. It takes skill to plan well and keep the process running smoothly. The teacher’s role in projects can range from a very directive to a more facilitative role, depending on student level and abilities and the project goals. Teachers need to provide guidelines and models for what the product should be, not necessarily so that students can copy them exactly, but so that they realize what is expected and why. To keep students most active, teacher planning should include ways to have students make their own decisions and work closely with each other. The teacher can help students to identify roles and/or to disseminate them, provide clear goals and benchmarks, model both the language and content needed for the project, and provide ongoing feedback and skills lessons as students require them. However, not all students can work so autonomously and it is often difficult for teachers to loosen control; in these cases, a more structured project with a very specific product can be used.

Challenges for teachers

In addition to the challenges of developing good projects, teachers may face school, community, and classroom obstacles to developing production projects. For example, projects often take time that standardized testing schedules or a rigid curriculum do not permit. Some teachers (or administrators) cannot abide noisy classrooms or relinquishing control to students. Another challenge for teachers is to understand how to provide enough scaffolding, or assistance, as students need it without interfering too much; they might also have to learn new technologies and learn how to assess the process and the product. All these challenges can be overcome with time and practice. The guidelines, tools, and resources mentioned in the next section can help teachers understand how to avoid or work through these challenges.

GUIDELINES FOR SUPPORTING STUDENT PRODUCTION

Guidelines for Designing Production Opportunities

In carefully planned projects, students understand the process and understand that the technology is secondary in importance to the content and goals of the project. Students are active learners; they make decisions, ask questions, write dialog, draw, direct, suggest, critique, and disagree. Students have the opportunity to play many different roles. Students who are not as competent in one area, for example, students whose language proficiency is not at grade level or those who have difficulty performing certain tasks, have the opportunity to work in other areas. However, the work of all students is valued and none of the students is exempt from working toward the final goal. By requiring that learners ask each other for help and evaluate one another’s work, the teacher provides frameworks of support (scaffolding) and guides learners to use valuable resources (their peers). Some of the guidelines for designing effective production projects are discussed here.

Guideline #1: Focus on process. This is important because often while creating projects, learners may get caught up in the graphics and other “fun” parts of production and lose some of the project’s opportunities for learning. Teachers must ensure that the task is devised so that students focus on the use of the language and content that are to be learned and used. Designing opportunities means:

Establishing both language and content goals that students understand

Involving students in the evaluation of content and process

Helping all students be actively involved in every aspect of the project

To help students get the most out of the process, the teacher can assign teams roles for each stage of the infomercial project. Students should be familiar with these roles because they have used them before. Each stage can have, for example, a Technology Operator, an Editor, a Team Liaison, and an Idea Generator. Team members redistribute the roles for each stage of the project so that all students have a chance to work to their strengths and also improve on their weaknesses. At each stage, the teacher, the school technology coordinator, and the library media specialist can work with an expert group (one member of each team) in a form of “cascade learning” to train students who are playing the role of Technology Operator. In different stages, for example, the Technology Operator is responsible for Internet searching, the digital camera, the editing software, and word processing. In each stage a different student is the Editor, who is responsible for both editing text documents and completing project paperwork. A third team member, who serves as the Team Liaison, works with other students and the teacher as a representative of the team, and an Idea Generator leads the development of the different stages of the project.

By focusing on all students being actively involved with content and language, teachers can assist learners in completing a process that will meet their goals and result in a useful product. ELL students, even those not at grade level in reading and writing, can be very successful at learning and teaching the technologies, generating ideas, and working as Liaison. These students can be encouraged to take on the role of Editor in the last stage of the project when they are familiar with the vocabulary, ideas, and tasks involved in the project. In this way, teachers can help them work from their strengths to developing their weaknesses while still holding them accountable for each part of the task.

Guideline #2: Use an authentic audience. Research on student production shows that students work harder when their work will be viewed by others. However, publishing student products for only the teacher to view generally is not enough to support this kind of motivation and effort. Instead, learners need an audience that is external to the immediate classroom and that cares about and has knowledge of the product, because such an audience will provide useful, authentic, and effective feedback. The audience should also be able to engage in interaction around both the process and the product and should clearly understand their roles in the project. Finding such an audience can be a difficult task, but it is one that students and teacher can share. For example, students might suggest that their reports on the first Gulf War be read by veterans of that conflict. The teacher can ask for volunteers from a veterans’ electronic list or a local veterans organization. Remember that providing student products to an authentic audience in the public sector, for example, on a Web site that has open access, means that safety and other issues must be considered (these issues are discussed in chapter 3).

Guideline #3: Teach the tools. It is important that students understand how to use the computer tools that might help them in their production process. Students do not need to understand every component of the program, but the salient features that support their current process should be clear. This information, like all important content, should be presented in a variety of ways for all learners to access the instructions: graphically, orally, and in written form, at a minimum. ELLs and other students who may need extra help to understand have more chance to comprehend when the information is presented in many ways. Multimodal presentation also addresses the different student learning preferences present in every classroom. The teacher can decide to use expert groups to teach the technologies that her students need for their projects, such as video editing, word processing, disk burning, graphics, and downloading or copying clip art from the Internet. She can teach a subset of the students and they, as experts, teach other students in the class. Because each stage of the project requires different skills and tools, all students have a chance both to be the expert and to learn about different technologies from their peers. Students might see this as just another part of the project, but the teacher knows the power that students feel when they are allowed to be experts and how teaching others leads to greater learning. To deal with the challenge to learn the technologies for each stage of the project,

The teacher can call on part of the support network in the school, the information technology coordinator and library media specialist, to teach each group’s current Technology Operator. This way, the teacher learns as the students learn rather than trying to figure out multiple tools herself before the project begins.

Guideline #4: Understand the tools. It is important that students know not only how to use the tools but also that they understand the opportunities that each tool affords. To this end, teachers and learners can brainstorm the kinds of tasks that can be accomplished with tools such as a database program, a word processor, or a graphical organizer. For example, if students were to produce a newspaper, they would need to understand that graphical organizer software could help them brainstorm and lay out a process, but it could not help to format the newspaper in the way that a word processing or desktop publishing program could. Teachers and their students can consider how the use of the tools limits or structures what they can produce, and they can continue to add to the list over time so that students use tools that provide them the most effective opportunities for producing content and language.

Guideline #5: Scaffold experiences for all learners. Some students, such as ELLs and students with disabilities, may need extra time, help, and modeling while working on projects. To facilitate their understanding, teachers can present information about project instructions, goals, and outcomes in a variety of modes (written, oral, visual), as described previously. Presenting guidelines and tasks in multiple modes provides opportunities for English language learners and those with special needs to receive content and language input in a variety of ways and helps to support comprehension; it also addresses the needs of students who prefer to learn in diverse ways.

In addition, as in any effective learning experience, projects should start with learners’ knowledge in content, language, and technology and build from there. Teachers can provide scaffolds by breaking up the task into logical stages; encouraging students to use a variety of re- sources in different modes such as writing, graphics, and oral language; and providing examples and models during the process.

Figure 7.2 presents a summary of the guidelines for designing production opportunities.

TECHNOLOGIES FOR SUPPORTING PRODUCTION

What Are Productivity Tools?

Students can use a variety of tools in creating their media projects, all of which are suited to a particular stage or process. Productivity tools are those that maximize or extend students’ ability to create products, solve problems, and express themselves. With productivity tools, students can construct models, publish, plan and organize, map concepts, generate materials, collect data, and develop and present their work. Electronic productivity tools include hardware such as digital cameras and video recorders and many different kinds of software. Many teachers are familiar with at least some of the commonly used productivity software.

It is important to note that the production process does not inherently require the use of technology. Rather, technology is used as it fits into the plan and makes the process more effective and/or more efficient. In developing activities that result in a student product, teachers and students should reflect on why they might use technology during the process. As discussed earlier in this book, if the technology does not make the teaching and learning more effective or more efficient, other tools should be considered.

There are many examples in each category of production tools, including some that are made specifically for different student grade and ability levels. Different schools and class- rooms may have entirely different sets of these tools, but they work in similar ways. The tools do not necessarily make learner products better or more creative, but they can be more professional and easier to share with others. Some research shows that learners are encouraged to produce more while using such tools. The more output students produce, the more opportunities they have to learn both content and language. Check this text’s Teacher Toolbox for specific production tools.

Student examples

Student iMovie products in a number of content areas can be found across the Internet. Art, English, math, science, music, and social studies projects are represented. Many sites also include tips from teachers, including using iMovie in the science classroom and making commercials with iMovie.

Likewise, interesting projects at all school levels using PowerPoint in a variety of content areas, along with hints and tips on using PowerPoint in the classroom, can be found by searching “PowerPoint projects” + (grade level).

Tools for teachers

Productivity tools also provide opportunities for teachers. Grading programs and worksheet and puzzle-making software assist teachers in creating products to use in their classes and in being more effective in their instruction (see chapter 9 for more on teacher tools).

Overcoming challenges

With all the guidelines to follow and possible challenges to face, teachers might find creating and using production projects supported by technology overwhelming at this point. However, if teachers build on standards for content and language learning, focus on the process, provide effective scaffolds, and encourage the principled use of technology (in other words, grounded in research, standards, and effective practice), they can create an almost limitless number of possibilities for projects that can be effective learning experiences. In addition to those presented in the following section, activities in other chapters throughout this text also support production.

LEARNING ACTIVITIES: PRODUCTION PROJECTS

The production projects described here are not addressed to specific grade or language levels— those for which they are appropriate is a choice that the teacher, knowing her students well, can make. Instead, the multidisciplinary activities are grouped initially by the content area that is most central to the project. Sample emphases for goals in both content and language are provided for each project; these are the focus of task development and tool use. After the product is presented, the examples in each content area are divided into one of three technology categories. Examples in each content area include

One that employs basic technologies (those that involve simple or few features that are generic across many tools)

One that uses relatively more sophisticated technologies (those that require additional features or multiple tools or are relatively new)

One that could use advanced technologies (those that require more in-depth knowledge of the tool or tools that are more complicated).

This format demonstrates that production is not a result of the technology used, but that the technology use is based on the task goals and structure.

The project descriptions do not state the teacher’s role, the challenges that teachers may face, how scaffolding should be done, or specific name brands for each project. Think about these aspects as you read the project descriptions, and be prepared to answer the question at the end of this section.

English

Content and language goals: Culture, media, adjective use, descriptive writing

Product: Movie flyer

Basic technologies: Word processor or simple graphics program Students complete the following process:

Review movie flyers and advertisements.

Choose a theme for a movie that they would like to see.

Develop text about their movie that fits with the genre.

Use a word processor to type their text and use appropriate fonts and styles, leaving room for any photos or graphics.

Add fonts/graphics.

Work with other students to review and revise their poster.

Students can produce very inventive products in this project. Follow up by posting the flyers around the room and letting students comment on which movies they might like to see and why.

Content and language goals: Genres, elements of story, peer editing

Product: Digital montage

Sophisticated technologies: Word processor, simple authoring program, presentation program, digital camera (optional)

Students work in cooperative groups to:

Develop themes or stories in a chosen genre.

Develop auto-play presentations with graphics, sound, and text.

Edit with peers.

Share with the intended audience.

These tools permit a fairly basic montage, typically slide by slide. Classes of younger children often make a very authentic audience for this activity.

Content and language goals: Summary, dialog, culture, text comprehension

Product: Five-minute movie trailer

Advanced technologies: Word processor, digital editor, CD burner and software, digital cameras/ video recorders

Students work together to:

Create the script for a five-minute movie based on a book they have read.

Develop costumes and scenery as needed.

Film the movie.

Edit the movie and burn it to a CD or DVD or post to a safe video site.

Share the movie with the intended audience.

The moviemaking/video editing software seems to be a sophisticated technology, but it is actually easy to use—it can be expensive, however, and many people tend to associate expensive technologies with higher levels of technical skill. Avid DV is free video editing software for the PC, as is iMovie for Apple/Macintosh computers. This activity is an excellent assessment and provides a different take on post-reading activities.

Social studies

Content and language goals: Idioms, slang, humor, current events/ politics

Product: Magnets and bumper stickers

Basic technologies: Word processing or presentation software with magnet or bumper sticker paper

After researching and discussing a current event and related language, students:

Develop a slogan or saying, explain the meaning and purpose of the slogan.

Revise based on classmates’ or others’ comments.

Type their sayings into a word processor and print.

Display for an appropriate audience.

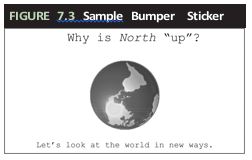

Even students with less advanced English proficiency can come up with some witty and thoughtful sayings for this activity. Other content areas can also make use of this kind of task. See Figure 7.3 for an example of a bumper sticker that questions the “top-down” view of maps and globes.

Content and language goals: Reporting, five W’s (who, what, where, when, and why), historical facts, extrapolation

Product: Simple newsletter for a historical organization

Sophisticated technologies: Desktop publishing software, Web search engines, scanner

Creating a newsletter is a common activity in many classes in which students:

Collect historical information from both electronic and print resources.

Type their articles using a word processor.

Include whatever graphics are necessary, using a scanner if available.

Edit, headline, and lay out the articles.

Print, copy, and deliver the newsletter to relevant readers.

Simple newsletters are often the most interesting. This activity includes many different roles that can assist ELLs and other students who need extra time or feedback to complete their tasks.

Content and language goals: Reported speech and other genres, current events, humor, titles

Product: A newspaper, complete with political commentary, cartoons, features, and ads

Advanced technologies: Depends on content, but a desktop publishing package, graphics package, word processor, digital image editing software, and others could be used.

Students

Create and assign job responsibilities.

Collect historical information from print, electronic, and human resources.

Create their part of the newspaper using appropriate technology.

Work with team members to revise and improve their work.

Edit; write headlines, captions, bylines; and design the layout.

Print, copy, and deliver; solicit feedback.

Students can publish more than one issue during a semester, or use the one issue as a springboard for additional projects and discussion. Roles can change during the additional issues as students learn and become more comfortable with different language and tasks.

Social Studies Sample: Latin America Projects

Sixth-grade students in Washington State’s Kent School District present their Latin American projects at http://www.kent.k12.wa.us/. The products are simply designed examples of research that the students did to explore countries in Latin America. Figure 7.4 presents an example of one student’s product.

Science

Content and language goals: Descriptive language, inventions

Product: New invention

Basic technologies: Word processing, paint program (optional).

During a unit on inventors, learners:

Design a new invention that they would like to use.

Type a clear and complete description of the invention.

Have another student try to draw their invention from the description.

Revise.

Post so that other students can try to draw it.

Compile the drawings and descriptions into a catalog.

This activity allows learners to write as much or as little as they can and practice process writing while focusing on science content. The catalog can be used for a variety of follow-up activities, such as writing stories about the new inventions, calculating costs of making the product, and so on.

Content and language goals: Patents, inventions, persuasive language, descriptive language

Product: Patent application

Sophisticated technologies: Desktop publishing software, graphics software, scanner.

In teams, students:

Explain their inventions clearly in text, comparing them to existing inventions as necessary.

Draw their inventions, scan, and import their pictures to their application document.

Complete a patent application form.

Receive feedback from evaluators (e.g., local experts, the teacher, other students) who decide which should be awarded patents and which need more work and why.

Revise.

Students can have roles that help them to perform their project tasks.

Content and language goals: Instructions, imperatives, inventions, and inventors

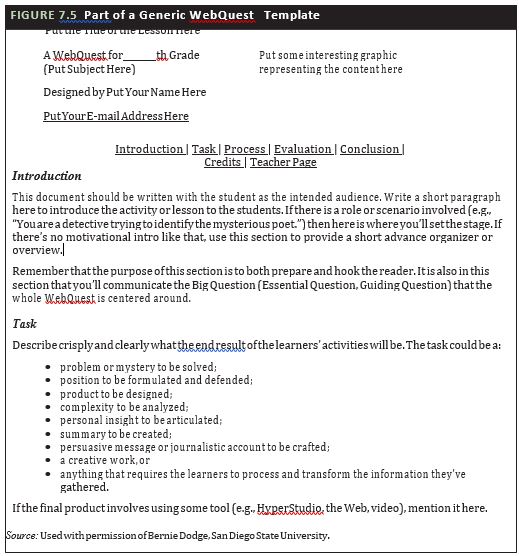

Product: A WebQuest

Advanced technologies: An electronic encyclopedia, word processing and graphics software, HTML editor, or Web page creation software

After working with WebQuests, student teams:

Review criteria for WebQuests.

Download appropriate templates from Bernie Dodge’s WebQuest site at http://webquest.org (see Figure 7.5).

Develop a plan for creating a science WebQuest.

Design each section, using and including appropriate resources.

Complete and post their WebQuests for evaluation.

Student teams can also choose one segment of a whole-class WebQuest project to work on, or they can improve a WebQuest that they have participated in.

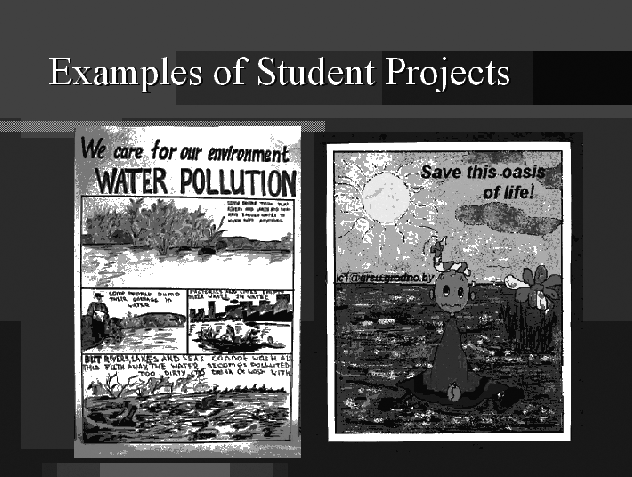

Science Sample: International Clean Communities Project

In one science-based project, secondary students in Belarus and the United States worked together online and traveled to work face to face to understand waste management around the world and increase communication between these countries about environmental issues. One outcome from their project was student-made posters addressing their concerns. Figure 7.6 presents examples of the posters produced by the students

FIGURE 7.6 Examples from the Clean Communities Project

Math

Content and language goals: Connectors, story writing, discussion, word problems

Product: Action mazes

Basic technologies: Presentation software or a word processor (can also be done in a web site builder or with an authoring program)

In an action maze, students must solve math puzzles and choose the correct answer to follow a story line. To make their own action mazes, in collaborative groups, students:

Decide on a math focus, content topic, and layout for their maze.

Write the text and decide how it will branch at decision points.

Find or create necessary graphics.

Create the maze in an authoring program.

Share it with peers.

Producing and using action mazes (Egbert, 1995; Healey, 2002; Holmes, 2002) can facilitate discussion, collaboration, and creativity in both the creators and the users.

Content and language goals: Question formation, percentage, graphs, reporting

Product: Peer survey

Sophisticated technologies: Spreadsheet

Students choose an issue that is important to them and:

Design a survey to gather student opinions.

Interview peers or other target audience.

Use a spreadsheet to calculate results and make graphs.

Present the results to the administration or other authentic audience.

Students can propose a new traffic light in front of the school, additions to the cafeteria offerings, or new books for the school library while working on math content and language.

Content and language goals: Area, house vocabulary, measurement

Product: House design

Advanced technologies: A computer-aided design program. The teacher assigns a specific total house area, and students:

Brainstorm and/or research the kinds of rooms and their relative sizes that people might want in a home.

Work with the CAD program to create their house to the specifications.

Revise to meet the total house area given.

Present the house plan to an authentic audience.

By creating and producing with other students who have different backgrounds and ideas, learners improve their content knowledge and language abilities while also increasing their cultural capital.

Student Samples: High Tech High

For examples of student work that integrates math across the curriculum, see the student projects page of High Tech High (https://www.hightechhigh.org/student-work/student-projects/). From baking bread to community study, elementary through high school students are putting math and technology to work in amazing ways.

Production projects can also be designed to address specific topics and language areas. Following are examples of language skills and vocational skills learning.

Language skills

Content and language goals: Vocabulary, definitions, spelling

Product: Puzzle

Basic technologies: A puzzlemaker program. Students use the vocabulary under study and:

Choose a puzzle type.

Create the puzzle text (typically clues or definitions for each word).

Create the puzzle.

Share it with peers.

Students are active when the teacher allows them to take responsibility for their learning, including creating opportunities for practice and assessment.

Content and language goals: Story elements, sentence formation, cohesive devices

Product: A book

Sophisticated technologies: A book publishing program

Students work with a given topic or develop one of their own into a book.

Students:

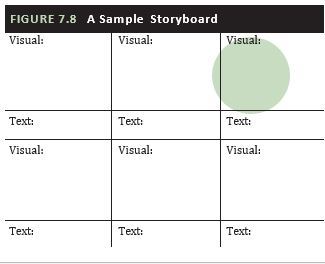

Complete a storyboard with text and possible graphics (a sample storyboard is shown in Figure 7.8).

Revise for grammar and surface features.

Create the title, text, and graphics in the software.

Edit as necessary.

Students can share their books with parents or students in another class or grade level. Using software available for different technical levels and language abilities can make this project easy and structured.

Content and language goals: Question and statement formation, explaining

Product: Interactive quizzes

Advanced technologies: A Web page composer program or another authoring/authorable software package.

Working alone or in groups, students:

Choose the format, questions, and answers for their quiz and decide on the type of feedback to be provided.

Create their quiz.

Give their quiz and take those that other students have made to study for the teacher’s version.

Like the simpler puzzlemaker, the products in this project help students study, practice, and review. They can also reinforce correct answers and help learners to understand plausible mistakes.

Vocational skills (community/business)

Content and language goals: Occupations, small talk, future verb tense

Product: Business cards

Basic technologies: Simple word processor Students prepare for their possible futures and:

Think about what they might like to be when they are older.

Decide on the company and location where they want to work (authentic or fictitious).

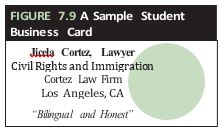

Design a business card with their name and work information and print on precut business card stock (see an example in Figure 7.9).

Role-play their business selves and hand out business cards to their peers.

This project is great for English language learners because it does not require much text and it provides practice in small talk.

Content and language goals: Résumé content, book characters, business language, past tense, formatting

Product: Résumé

Sophisticated technologies: Advanced word processing features or desktop publishing program.

In this multidisciplinary project, students:

Answer questions on a character or author’s life. The questions require them to discover information typically required for résumés.

Create their character’s résumé using a word processor.

Compare to the work of others who have chosen the same character, or check with someone who knows the character.

Revise the résumé.

Present their character to the class.

This activity facilitates extensive interaction among students and helps students to understand elements of resumes and of literature.

Content and language goals: Question formation, business register, surveying, calculating

Product: A business (bake sale), including business cards, a survey, a schedule, advertisements

Advanced technologies: Spreadsheet, advanced word processing features, graphics package

Students, with members of the school parent or student organization:

Decide on business type and create and distribute roles to each student.

Make business cards.

Create a survey asking students at the school their preferences (for favorite bake-sale cookie types or whatever the business will be).

Enter the numbers into a spreadsheet and calculate percentages.

Decide on what will be sold and when, how advertising will be done, and other issues.

Create the advertising and the product.

Sell it.

Measure their success by comparing survey results to actual sales.

As long as schools have bake sales, they can be used for learning purposes. In this activity, all students have many choices of how to work, which supports diverse abilities and skills.

Adapting Activities

The steps presented in each project are suggestions and can be adapted in many ways. Some of these activities can also be done using non-electronic technologies such as pencil and paper. However, in most cases the use of technology adds to the process by giving the products a professional appearance and giving students more time and more resources for creating and learning. In addition, teaching learners through and about technologies can help them accomplish many language and content goals while also learning valuable technology skills.

The examples above are only a few of the activities that facilitate production, and thereby content and language learning. There are others throughout this text and more examples can be found all over the Web. Teachers who want to design their own effective production activities should keep in mind the principles and standards from chapter 1 and also reflect on the process that students will use as they produce. All of the projects can be adapted to use different technologies and to work in different contexts. Even the most sophisticated products can often be completed with basic technologies, although the products will be different in some ways. These examples also illustrate what great products can come from simple technologies and how goals can be met effectively through production.

ASSESSING PRODUCTION PROJECTS

Evaluating production projects can be different from evaluating other kinds of projects in that one major outcome is tangible; however, it is similar in that both process and product must be evaluated to provide a true understanding of the learning that has occurred. Evaluating the process and product means that teacher and students must be involved in ongoing assessment throughout the project.

Teachers and students can use one, more than one, or all of these assessments for project- based learning:

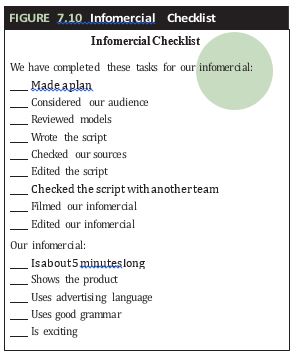

Team activity reports—These can be written or oral, individual or group, and explain what the group and/or individual has been doing and what help they need to continue. One team activity report is an infomercial checklist, as seen in Figure 7.10. Notice that this assessment helps students to practice language, in this case past and present tense. ELLs and others who need to work on basic language skills are supported by the simple language used in this assessment.

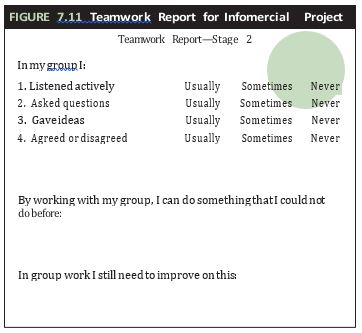

Peer teamwork reports—Students report on how the collaborative process is working, where it breaks down, and what they are learning by working with their team. These reports can take any number of forms; Figure 7.11 shows one possibility for n infomercial project.

Self-assessment—Students can be asked to describe their progress and outcomes according to the rubric criteria, or they can be asked to reflect on how well and in what ways they participated in their group. Students could be asked in which role they performed the best, in which they achieved the most, which role was most difficult and why, and which they preferred. This information will help students assess their strengths and weaknesses and the teacher to plan future projects.

Teams assess each other—This can be formal or more informal and based on general criteria or on whatever teams find to comment on. During an infomercial project, the teams can assess each other informally based on what they see as strengths and weaknesses in other teams’ scripts. Teams can comment, for example, on the interest that the script generates, others how well written it is, and yet others how clearly the product is described.

Outside stakeholders—External reviewers can create their own criteria for the product or use criteria provided by the teacher.

These assessments can take place orally, in written form, or both. Students, such as some ELLs who are unable to respond in these formats, can draw pictures or present their information in other ways.

FROM THE CLASSROOM

Projects

I use a lot of projects as a means to teach concepts. This approach works for me, because I can have the same basic thing that all kids are doing, but adjust expectations or requirements depending on students’ various abilities. I feel that the projects give the kids problems to solve and help encourage critical thinking. I also think projects on the computer that require students to make an end product really encourage this as well. The computer projects have been great for my ELLs. (Susan, fifth-grade teacher).

Roles

I have used the strategy of assigning roles to students for group work. I’ve used it in the middle school and with adults. You may choose to play a smaller part in this and list the different roles on the board: time keeper, recorder, etc., and have students decide who will do what in their group. Assigning roles also eliminates the possibility of hitch-hikers, students who just go along with everything and don’t contribute. For younger students I would have jobs assigned at random or make smaller groups with fewer roles. Just simplify it and it will still be successful.

Rotating also helps everyone participate in the different types of roles available, which you can alter according to your lesson plans and expected outcomes. (Gabriela, second-grade teacher).

CHAPTER REVIEW

Key Points

Define production.

Production is the development, through a process, of a tangible, manipulable outcome (a product). The product is the impetus behind the development of each stage of the production project.

Describe the benefits of student production for learning.

The benefits of student production for learning include student gains not only in language and content but also in social skills, critical thinking and planning, communication, cultural knowledge, and evaluation.

Explain the role of process in production.

The production process is a carefully designed process and crucial for the success of the project. Planning, development, and evaluation are three general stages in the production process.

Discuss guidelines for supporting student technology-enhanced production.

Teachers need to focus on the process, provide authentic audiences to view student work, understand and teach the tools, and provide scaffolds for students. In addition, the teacher’s role varies from project director to project guide depending on the structure and goals of the project. Research supports the use of production for student learning, although there are challenges for teachers, students, and administrators in designing and carrying out production projects.

Describe technologies for supporting student production.

Tools such as word processors, spreadsheets, draw programs, and presentation software can support production. The use of production tools alone, however, does not result in learning. As noted above, production projects must be carefully planned so that they meet both con- tent and language objectives and support other learning goals.

Evaluate and develop pedagogically sound technology-enhanced production activities. A wide range of products can fit a variety of goals; the role of technology is to support the goals, not to determine them. Teachers and students have a range of choices in meeting production goals. Most important, production can facilitate the achievement of all students, regardless of language background, learning preference, or physical ability. Examples of both teacher and student products and the results of their creative processes are easily accessible on the World Wide Web. A review of some of these Web sites can inspire teachers and learners to integrate and use production tools in their teaching and learning and serve as models for product development.

Design appropriate assessments for technology-enhanced process and product.

Just as there is a huge range of production projects, there is a great variety of assessments that teachers and students can use to assess them. Most important is that both process and product are evaluated, and that students are involved in the assessments.

CHAPTER EXTENSIONS

To answer these questions online, go to the chapter 7 section of the Extensions module of this text’s Companion Website (http://www.prenhall.com/egbert).

Adapt

Choose a lesson for your potential subject area and grade level from the technology-enhanced lesson plan archive at KidzOnline (http://www.kidzonline.org/LessonPlans/). Use the Lesson Analysis and Adaptation Worksheet (in the Teacher Toolbox) to consider the lesson in the context of production. Use your responses to the worksheet to suggest general changes to the lesson based on your current or future students and context.

Practice

Write objectives for a technology-enhanced project. Write specific content and language objectives. Share them with a peer and revise them as necessary. Use the “objectives” table from chapter 1 as needed.

Create student roles. Review the learning activity examples in this chapter. Choose three of the projects and suggest what roles you might create for students and who an authentic audience could be for each of the three projects.

Assess technology-enhanced learning. Choose one or more of the learning activity examples from the chapter and develop an assessment plan. Address who will be assessed, when, in what categories, based on what criteria. Also suggest how you would generate an overall assessment for the project.

Explore

Create a production handout for students. On paper, use graphics, text, and any other modes you can to outline for your students a production project that you might use in your class. Include information that explains to students the content and process of the task. Add a brief description of how the task process will be accessible to all students, regardless of language proficiency, content knowledge, or physical abilities.

Create a quick reference for production software or hardware. One way to learn a piece of software or a technology is to make a reference to help someone else. Choose a piece of software or hardware that you might use in the production process in your classroom. Explore your choice, examining the features and learning about the opportunities that it offers. Then create an explanation for students on how to use it. Be sure to make your reference appropriate for diverse learners.

Examine a production project. Choose a production project from a text, Web site, or other resource that is relevant to your current or future teaching context. Explain how the project you choose meets the guidelines and provides the opportunities mentioned throughout this chapter. Describe how it might be adapted to better meet the needs of all students and to use technology more effectively.

Create a production project. Review your content area standards and any other relevant standards. Choose a topic that works within these standards and other curricular requirements for your state or region and develop a technology-enhanced project around it.

REFERENCES

Adams, M., & Ray, P. (2016). Active learning strategies for middle and secondary school teachers. Available: http://www.doe.in.gov/sites/default/files/cte/active-learning-strategies-final.pdf

Bazeli, M. (1997). Visual productions and student learning. ERIC 408969.

Blumenfeld, P., Soloway, E., Marx, R., Krajcik, J., Guzdial, M., & Palincsar, A. (1991). Motivating project-based learning: Sustaining the doing, supporting the learning. Educational Psychologist, 26(3/4), 369–398.

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. New York: Collier Books.

Egbert, J. (1995). Electronic action mazes: Tools for language learning. CAELL Journal, 6(3), 9–12.

George Lucas Foundation. (2005). Instructional module: Project-based learning. Retrieved June 30, 2007, from the World Wide Web: http://www.edutopia.org/projectbasedlearning.

Healey, D. (2002). Teaching and learning in the digital world: Interactive Web pages: Action Mazes. Retrieved February 11, 2005, from the World Wide Web: http://oregonstate.edu/~healeyd/ups/ actionmaze.html.

Holmes, M. (2002). Action mazes. Retrieved from the World Wide Web, February 11, 2005: http://www.englishlearner.com/llady/actmaze1.htm.

Male, M. (1997). Technology for inclusion (3rd ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

San Mateo County Office of Education. (2001). The multimedia project: Project-based learning with Multimedia. Retrieved February 11, 2005, from the World Wide Web: http://pblmm.k12.ca.us.

Thomas, J. (2000). A review of research on project-based learning. San Rafael, CA: Autodesk Foundation.

Feedback/Errata