10 Chapter 8 Supporting Student e-learning

Although many states and organizations are developing standards for distance education, a widely accepted set does not yet exist. Rather, distance educators agree that e-learning should support content standards and state learning goals in the same ways that traditional classroom learning does. In addition, participating in distance learning can help students meet many standards, such as using technology tools to collaborate, communicate, solve problems, and inquire.

Specific guidelines for different types of online learning are being developed, but for now teachers can think about how e-learning might better help them meet curricular goals and student needs. If e-learning cannot meet these goals and needs, then a different instructional strategy should be used.

OVERVIEW OF E-LEARNING IN K–12 CLASSROOMS

What Is e-Learning?

Because learning through or with the aid of digital technologies like the Internet is a relatively new phenomenon that expands continuously, there are many terms to describe it and few consistent understandings of what these terms mean. For example, common terms to describe some or all aspects of learning through technology include distance education, distributed learning, open learning, online education, virtual classrooms, blended learning, and e-learning. Clearly, e-learning is not a learning goal per se but rather a structure or context for technology-supported learning through which content, communication, critical thinking, creativity, problem solving, and production can all take place. For this book, the term e-learning (short for electronic learning) means that the learning environment:

Is enhanced with digital technologies, particularly but not necessarily computer-mediated communication software (CMC, described in chapter 3)

Involves learning situations where interaction between the student and instructor is mediated, or bridged by technology, in some way

Uses technology in an ongoing and consistent way, not in isolated events

Is learner-centered

Focuses on students with instructor and student with student interaction

Uses a wide variety of resources

According to this definition, e-learning can occur in contexts such as

A face-to-face (f2f) classroom in an online chat

Video conferencing

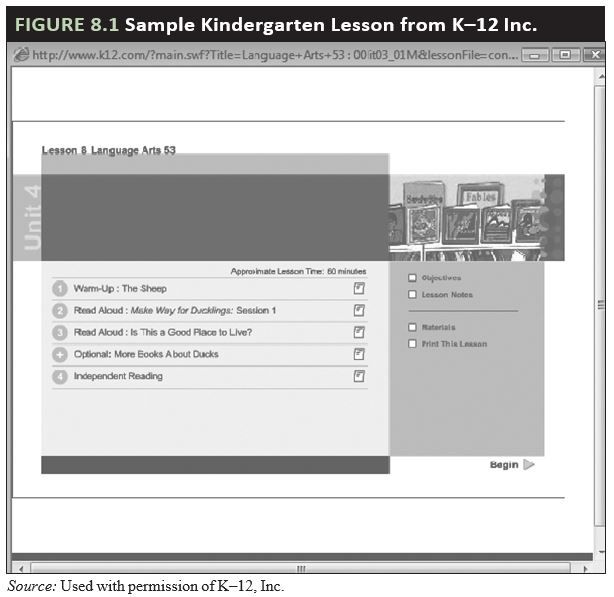

A virtual school that is completely online (for examples, see the Idaho Virtual Academy, http://idva.k12.com/. A lesson provided by K–12, Inc. is shown in Figure 8.1; Florida Virtual School, www.flvs.net/)

Situations that combine these options (see the U.S. government’s Star Schools at www.ed.gov/).

All of these examples fit the definition of e-learning in this chapter.

A combination of face-to-face and electronic learning can be referred to as blended, hybrid, or mixed-mode environments. Generally, in blended contexts, f2f time is partly given over to e-learning experiences. These optimal environments allow teachers to blend the best of f2f and online learning. Abate (2004) explains, “The traditional face-to-face elementary classroom imparts the social contact that children need to guide their learning while the online, or Web-based, learning environment offers flexibility and opportunities not possible in a traditional classroom. To create a learning environment using both modes to enhance the

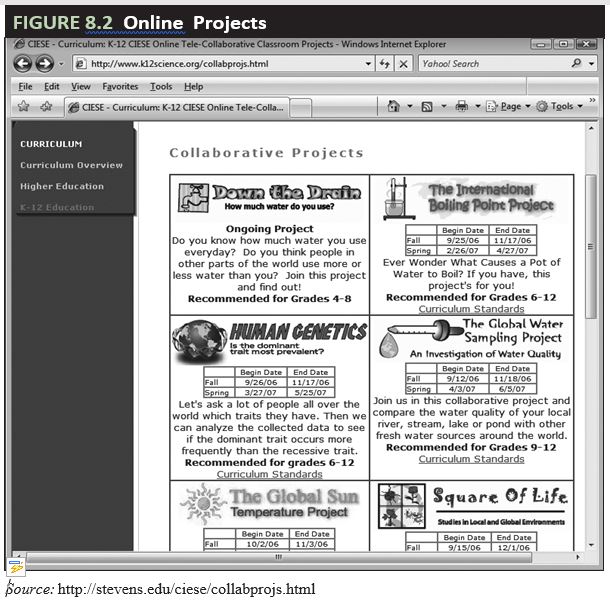

learning experiences of the students would provide the greatest benefit” (p. 1). Giarla (2017) notes many benefits of blended learning, suggesting that blending f2f and e-learning can result in higher quality achievement and better teaching. Figure 8.2 presents online projects that could be integrated into a blended learning environment.

As in most instructional contexts, three general components interact to comprise e-learning:

Instructional and learning strategies, such as collaboration, reflection, problem-solving, communication

Pedagogical models or constructs, which indicate how learning takes place

Learning technologies, including everything from Web sites to communication software and digital cameras (Dabbagh & Bannan-Ritland, 2005)

However, there can also be crucial differences between traditional learning in f2f classrooms and e-learning; for example, Dabbagh and Bannan-Ritland (2005) contrast the characteristics of traditional and Web-based learning as outlined in Table 8.1.

| Traditional Learning Environments | Web-based Learning Environment |

| Bounded | Unbounded |

| Real time | Time shifts: asynchronous communications and accelerated cycles |

| Instructor controlled | Decentralized control |

| Linear | Hypermedia: multidimensional space, linked navigation, multimedia |

| Juried, edited sources | Unfiltered searchability |

| Stable information sources | Dynamic, real-time information |

| Familiar technology | Continuously evolving technology |

Note: Data from Why the Web? Linkages, by M. Chambers, 1997. Paper presented at The Potential of the Web, Institute for Distance Education, University of Maryland University College, Adelphi, MD. Source: Dabbagh & Bannan-Ritland (2005).

Who Are e-Learners?

Today, students of all kinds are participating in distance learning through a variety of e-learning opportunities. According to the U.S. Department of Education, in 2005, 36% of school districts and 9% of all public schools had 328,000 students enrolled in some kind of e-learning. High-poverty districts were among the most ardent supporters of using e-learning to provide services that the district could not otherwise afford to provide to students (Setzer & Greene, 2005). By 2009-10, 53% of districts had students in online courses, and 1.3 million high school students were enrolled (National Center for Education Statistics, https://nces.ed.gov/). Clearly, the trend is growing and has no indications of stopping soon.

Most K–12 elearners access their online courses from their schools, which often provide onsite help for e-learners. However, home learners, homebound learners, juvenile detainees, alternative school attendees, and school dropouts also use e-learning resources. E-learning is flexible enough to meet their needs for easy access and alternative curricula. Although the majority of e-learners who study completely online are in high schools, even younger children are taking part in e-learning tasks in their classrooms. Schools generally provide e-learning for advanced study and remediation, but many schools and districts are also making a systematic effort to use e-learning in reforming what they do across their classrooms. For example, second graders are communicating regularly through email with experts about class content, and ninth graders are working with students in other countries through the Internet to understand culture.

Because distance education at the K–12 level is still developing, the full results of these changes will not be available for some time. However, preliminary research shows that, done well, e-learning environments can be effective for K–12 learners (see, for example, Cavanaugh, Barbour, and Clark, 2009). Because e-learning concepts and understandings change rapidly and the research cannot keep up, Conceicao and Drummond (2005) suggest that the best place to find out about e-learning in K–12 contexts is to look at Web sites that provide examples of how e-learning is taking place.

Contexts for e-learning

Many e-learning tasks and courses are interactive multimedia explorations among a variety of participants. However, some e-learning formats still replicate the isolating, one-way correspondence course. There is no one set format or way to conduct e-learning, but what it should not (and usually cannot) be is traditional teaching moved to a new medium. For example, in a text-based electronic forum, if the teacher monopolizes the discussion (the equivalent of offline lecture), it is easy enough for students to ignore her postings.

The use of technology for e-learning makes it imperative that teachers rethink how they teach and investigate what the new mediums afford. Such reassessment is necessary because during e-learning, communication can take place synchronously (at the same time) or asynchronously (at different times), and participants can be in a variety of spaces and places. The variety in these instructional features calls for a variety of approaches, as seen in the three scenarios that follow.

Scenario One—Videoconferencing

The teacher and students at four different sites videoconference twice per week for an hour each session. Students find materials on the course Web site, use online chat to work in teams to collaborate on assignments, and receive help from teachers at their local school site when they have questions and concerns. They email or fax their assignments or post them to their Web site for evaluation, and they each have an office visit with the teacher by phone or Skype once per month.

Scenario Two—Online Course

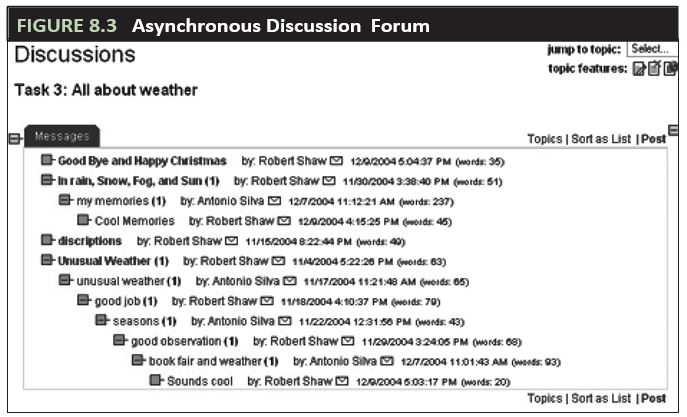

In a completely Web-based course, students who never meet their instructor f2f go into their course space in an online learning environment such as the free Canvas platform ( https://canvas.instructure.com/) and find instructions for the current assignment. As they proceed through the assignment, they interact with other students and the teacher asynchronously through the discussion forum. They can ask for help and feedback, post comments and Web site URLs, and participate in an analysis of the topic at hand. They also send and receive emails with the teacher and consult the online resources available in the course space, including rubrics for the activities. After they turn in (fax, email, or post) the final draft of their assignments, they receive comments and a grade in a virtual space online that is only seen by them. Figure 8.3 shows the interface of one electronic forum where an ELL student and teacher are discussing weather as part of a unit on creativity. In the threaded discussion shown, the comments are inset to show the order in which the comments were input and whether they are new messages or replies to a

previous message.

Scenario Three—Blended Learning

In an example of a hybrid or blended course, students in advanced high school science are released from two class periods each week to work on individual projects. They keep in touch with the other students and the teacher about their projects using an electronic forum where they post information about their progress.

…………………………………………

As discussed in chapter 3, students could participate in other e-learning activities including communicating with external experts, accessing remote resources, mentoring and tutoring students at other sites, and working in projects where students collaborate with external peers or other audiences. There are many variations on e-learning, but all must comply with standards and guidelines for effective teaching. Fifteen years ago Blomeyer (2002) noted what is still true today; that the most important understanding that teachers and administrators must have about e-learning is:

In the final analysis, e-learning isn’t about digital technologies any more than classroom teaching is about chalkboards. e-learning is about people and about using technology systems to support constructive social interactions, including human learning. (p. 5)

Characteristics of effective e-learning tasks

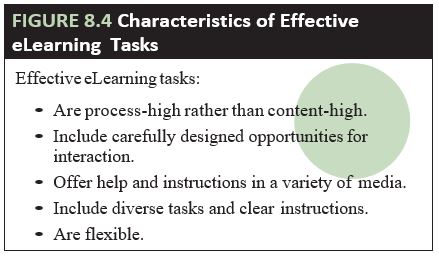

Small but critical differences exist between tasks in face-to-face classrooms and in online contexts. For example, Jackson (2004) contrasts content-high and process-high tasks that occur during e-learning. Content-high tasks, the most common in face-to-face instruction, are one-way resource dumps from instructor to student with little interaction. If this occurs during e-learning, students may drop the task or not do well because of the lack of support.

Process-high tasks, on the other hand, acknowledge the importance of interaction and communication among students and instructors before, during, and after the task. Employing process-high tasks is a principle emphasized throughout this text to support all learning goals and is especially important for online learning experiences (Tallent-Runnels et al., 2006). However, even process-high online activities lack the kind of student gestures, facial expressions, and other feedback that allow teachers to “read” how their students are doing. Teachers in f2f contexts find

this type of feedback essential during process-high tasks and must learn either to do without it or obtain it in another manner during online courses. To address this potential problem, effective e-learning tasks must have carefully designed opportunities for interaction. In addition, teachers can help students learn to convey their intentions through the use of text color and size (e.g., ALL CAPS MEANS SHOUTING), format (e.g., use italics for emphasis), and emoticons, or text-based emotion icons (find a complete definition and a list of emoticons at the What is . . . site at http://whatis.techtarget.com/).

In addition, effective e-learning tasks employ multimedia rather than one medium. If the interaction during e-learning is solely in writing it can pose a barrier to language learners and other students with different reading and writing abilities. To overcome this barrier, accompany instructions sent in an email message with a recording of the message and/or attach a handout with graphics.

To be effective, tasks must also be diverse and have clear instructions so that students are not bored or confused before they begin. To avoid confusion, effective e-learning tasks should include ways for students to:

Receive reinforcement.

Review or repeat any part of the task.

Ask for help or remediation for parts of the task that are not clear or are too challenging.

This is relatively easier to do in blended contexts because the teacher can interact f2f with students and understand their needs more readily.

Finally, because students typically work more independently when involved in e-learning tasks, extra time may be needed to complete tasks. Therefore, build flexibility into the assignment ahead of time. Characteristics of effective e-learning tasks are summarized in Figure 8.4.

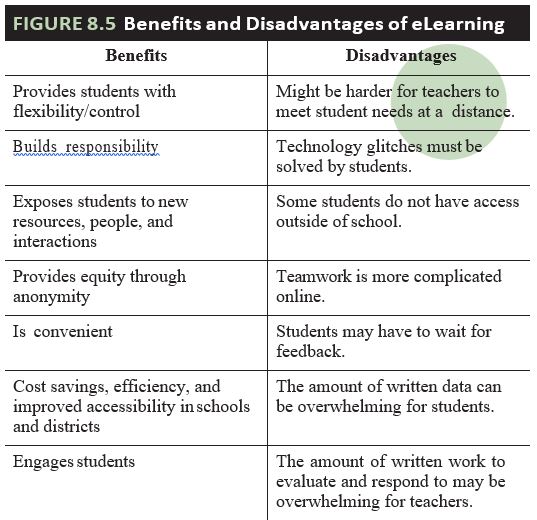

Student benefits from e-learning

Students can derive a number of benefits from participating in effective e-learning tasks. A Teacher’s Guide to Distance Learning, published online by the Florida Center for Instructional Technology (http://fcit.coedu.usf.edu/distance), suggests that e-learning can have the following benefits for students:

Flexibility/control. When students participate in true e-learning, they have more control over their learning. They can choose the pace, site, and format of their learning. Students in many e-learning situations can also choose what they wear to learn.

Responsibility. During e-learning, students are required to become active, responsible learners. To be successful, students must develop skills in working independently, in asking for help, and in interacting with fewer nonverbal cues from other participants.

Exposure. Often, e-learning exposes students to resources, people, and interactions that may not occur in traditional f2f tasks or environments. This idea was outlined in chapter 3 and throughout this book.

Interaction. During e-learning, students learn technology and have more opportunities to interact with teachers than in traditional classrooms. Shy students, those with limited language skills, and those with physical limitations can often have more time and more access to the interactions because they can read and respond at their own pace.

Anonymity/equity. When students are online, cultural, physical, and other personal attributes are not focal and are often invisible during interaction. The online format can be more equitable for students with noticeable speaking differences, physical disabilities, and other characteristics that might present barriers in f2f interactions.

Convenience. E-learning opportunities come in all shapes and sizes. While some require attendance or a starting date at specific times, others allow teachers and students to set their own schedules.

Overall, research shows no significant difference in student achievement between good f2f instruction and e-learning. In other words, if done well, both can work toward student achievement. However, in a way the comparison is a false one—students do different kinds of tasks during e-learning and they learn in different ways, and therefore it is important to offer a variety of options for learning, including face-to-face time. Researchers are looking into these outcomes more closely to see which factors promote what kind of achievement for which students. For example, according to an analysis of the research on distance learning, the 2016 National Education Technology Plan (https://tech.ed.gov/netp/learning/) concluded that:

Historically, a learner’s educational opportunities have been limited by the resources found within the walls of a school. Technology-enabled learning allows learners to tap resources and expertise anywhere in the world, starting with their own communities.

School and district e-learning benefits

In addition to student benefits, e-learning also has benefits for teachers, schools, and districts. According to the National Education Technology Plan (essential reading for any teacher; Office of Educational Technology, 2016),

Educators can design highly engaging and relevant learning experiences through technology. Educators have nearly limitless opportunities to select and apply technology in ways that connect with the interests of their students and achieve their learning goals. For example, a classroom teacher beginning a new unit on fractions might choose to have his students play a learning game such as Factor Samurai, Wuzzit Trouble, or Sushi Monster as a way to introduce the concept. Later, the teacher might direct students to practice the concept by using manipulatives so they can start to develop some grounded ideas about equivalence. (n.p.)

These are benefits that cannot be overlooked in this age of shrinking funding, teacher shortages, and increased accountability. Of course, there are also disadvantages to e-learning.

Disadvantages of e-learning

The disadvantages of e-learning, like the benefits, vary by context. These include, for example:

Teachers might find it difficult to meet all learners’ needs in a completely online course since some need more structure or f2f interaction than exists in e-learning contexts.

Learners at a distance from the teacher might not have support for technical problems.

Students who do not have access to technology outside of school may not have the option to participate.

Teamwork is more complicated in online contexts because the typical classroom immediacy of contact is mediated by access to and use of the technology.

If information and resources are not carefully chosen, the learner can be overwhelmed with the amount of information available online.

The often-huge number of discussion postings and assignments for teachers to check in completely online classes might prevent students from getting the direct, immediate feedback that they need.

In spite of these difficulties, adding e-learning to f2f courses, such as integrating a discussion board or class blog, for example, can enhance effective learning. In addition, the “broader educational community” can contribute to the experiences.

E-LEARNING PROCESSES

The benefits from e-learning will accrue if participants pay careful attention to the processes involved. These include:

The teacher’s (or instructional designer’s) process of creating e-learning opportunities

The student’s process in taking those opportunities

According to Bowman, teachers and instructional designers generally use the following process to create and implement successful e-learning experiences:

Plan—assess the learners and the technology.

Design—develop learning objectives that advance content to [achieve] desired learning outcomes.

Develop—match learning objectives to media using multiple strategies to engage creativity (e.g., lecture, text, audio, video, case study, team projects, practical exercises and individual assignments, interactive problem solving, student-to-student interaction).

Implement and evaluate—use iterative (repeating) design so activities can be improved and updated easily. (n.p.)

During e-learning tasks, students must:

Understand the assignment.

Learn the technology to a level sufficient to complete the task(s).

Interact with the online community to build understandings.

Complete the assignments and related assessments.

Depending on the goals of the e-learning course, students will also use processes to solve problems, communicate, produce, and meet other learning goals.

Teachers and e-learning

Teachers must often learn new skills and take on new responsibilities in e-learning environments. Ko and Rossen (2017) note that online instructors, while sharing the need for good communication and organization skills with f2f teachers, also require a different set of skills. These include:

Planning for asynchronous or other distant interaction

Organizing detailed tasks and instructions

Using presentation skills specific to e-learning environments

Using questioning strategies for different (often unseen) students

Involving students across different sites

Using student progress reports and learning analytics

Connections to social media

Keeping updated on the technologies

These needs might require that the instructor learn new technologies and teaching strategies, as described in the following section.

The teacher’s role

There are cases where electronic instruction consists of lectures posted online, but these are not good examples of e-learning. The teacher’s role in e-learning is to be a facilitator, making sure that students are engaged in working toward learning goals. In this role, teachers can:

Build rapport with students by meeting with them f2f or working on a personal basis at the start.

Encourage e-learners by addressing feedback to them by name, and guide them in finding their own answers.

Make sure students are spending their time effectively, not spending a disproportionate amount of time on assignments but working efficiently toward the course or task objectives.

Divide classes into discussion groups. More than six members in a group tends to isolate at least one member. Fewer tends to shut down the group in the event two members become unavailable (Jackson, 2004).

Require individuals to identify their discussion posts clearly. Also require groups to summarize their group discussions so that students do not need to read every posting.

Create a presence in the course or task. Let students know that the teacher is observing and is available.

Above all, teachers must be able to promote successful interaction during e-learning.

Challenges for teachers in creating e-learning opportunities

There are barriers that teachers may face when first using e-learning. For example, the technology chosen for the course can get in the way of instruction because it mediates in ways that prevent teachers from receiving and providing visual cues or instant feedback. Therefore, teachers and course designers must make instruction direct and concise. They must also take into consideration:

The difficulty for students of reading extensive text on a monitor

The time it takes students to type their responses

The pace and amount of information such as video clips, discussion postings, and Web- based data

To work around these challenges, during course design teachers can work with an instructional designer, a technology specialist, the library media specialist, and even students. Once the course or task is designed, teachers can and should partner with the students’ on-site teachers and counselors. To see an example of teachers partnering with others, take the online tour of Virtual High School at www.govhs.org/website.nsf.

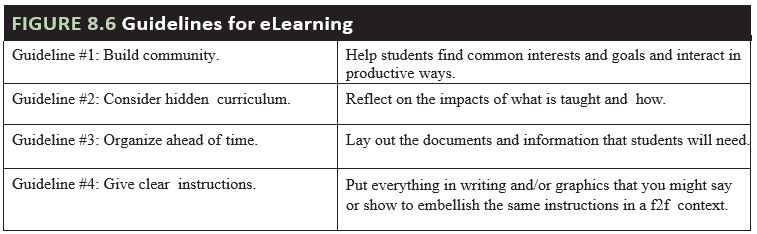

GUIDELINES FOR SUPPORTING STUDENT E-LEARNING

This chapter has shown that e-learning is not entirely different from f2f learning, nor does it require completely different teaching skills. Likewise, the guidelines in this section apply to all learning contexts, but they take on importance in e-learning contexts, whether hybrid or fully online.

Guidelines for Designing e-learning Opportunities

Four guidelines for building effective, interactive e-learning opportunities are presented here.

Guideline #1: Build community. Whether participating in a Web-based course or a technology- enhanced homework assignment, students need to know that they are not alone and that others are working toward the same goals. It is important that students identify themselves as members of the learning community whether they are face-to-face with other students or in a virtual on- line classroom. Strategies for building community include encouraging all students to participate, providing support for group work, connecting learning to students’ lives as a group, and incorporating team-building exercises into tasks. Community can also be built using strategies such as all participants using others’ names when they are interacting online, posting profiles (and possibly photos) that help learners choose group members and get to know more about each other, and having online chats to give learners a chance to work together in real time.

Guideline #2: Consider the hidden curriculum. In any curriculum, there are elements that are not explicitly taught (i.e., they are “hidden”). These include values, relationships, societal

norms, and expectations. These are essential elements that students are expected to learn. E-learning also has its hidden curriculum, such as the cultural and social impacts of e-learning. Questions for teachers to answer that address this hidden curriculum include:

Who benefits from the way information is being presented?

What dominant ideology, explicit or implicit, is being espoused?

What is credit being given for in the course? Participation? Writing well? Citing the course texts?

What kind of student will succeed or fail in this context?

How is technology valued?

Who should be allowed to participate in this e-learning experience?

This last question arises from the economic impact of courses that are offered for a fee.

Guideline #3: Organize ahead of time. A Web site or learning management system (LMS) like Canvas or pbworks that accompanies e-learning opportunities and provides the following can help students and teachers work more efficiently and effectively. This site should include:

One-stop location for up-to-the-minute course announcements, materials, assignments, etc. Digitized information is also easily modified and maintained.

Resource and access capabilities for all students.

A way to display and receive resources which may otherwise be difficult to assemble or locate, such as samples of assignments (good and bad with reasons why), or hot links to Web sites used for course assignments (for example, analyses of corporate annual reports).

Online archive of course slides, graphics, digitized video, for student retrieval and study on their own time.

Digitized multimedia that illustrate course concepts, especially those that are interactive. (n.p.)

By organizing ahead of time and creating a Web site with all the essential information and tools, teachers will have more time to dedicate to the important interactions necessary to the success of e-learning.

Guideline #4: Give clear instructions. Part of organizing e-learning is clarifying what students need to do and how they should do it. Because students are generally not in the same room as the teacher and typically cannot ask questions on the spot, the instructions for e-learning tasks need to be very explicit and models, if available, should be accessible to students. This seems easier than it really is—classroom teachers usually rely on being able to “read” their students to clarify and add to instructions, and it takes practice to write good instructions that do not need further explanation. Figure 8.6 summarizes the guidelines for e-learning.

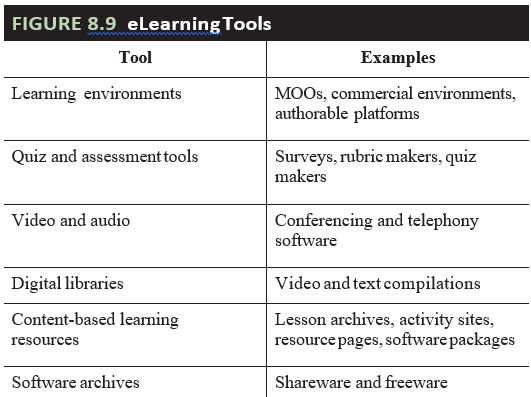

E-LEARNING TOOLS

Because e-learning occurs in so many configurations and contexts, many different tools, alone or in combination, are used. Electronic tools for e-learning can include any of the tools mentioned throughout this text (CD-ROMs, videos, social media, and so on). From printed materials such as textbooks and handouts to simple audio material such as audiocassettes to the latest computer technologies, almost any tool can be integrated into e-learning. However, most formal e-learning contexts currently include interactive technologies such as the World Wide Web, email, and video technologies. It is not within the scope of this text to discuss how to use all the tools that are used for e-learning, but the annotated collection presented in this section can help teachers begin an investigation of common e-learning tools. Most of the tool Web sites include tutorials and other support for new users.

In addition to an Internet connection, a Web browser (e.g., Google, Internet Explorer, Firefox, Safari) with add-ons (i.e., mini-applications or plug-ins) will help students listen to audio, see video, and compose and send email. Other tools that can be used during hybrid and on-line classes include the following.

Learning environments

Learning environments provide online or “virtual” places to interact and post course content. Some environments are commercially produced, others are free. Some are authorable, or able to be changed by users, while others cannot be changed. Many commercial environments come with preset content; others allow the use of homegrown (locally produced) content. Each tool has specific strengths and weaknesses that can best be found by using it in context (most offer a demonstration version and technical assistance for evaluation purposes).

Some popular learning environments are listed here. They typically include some preset features such as asynchronous threaded discussion, internal email, document and link posting, and synchronous chat capabilities. For less structured environments, see authorable platforms later in this section.

Commercial environments

Blackboard (www.blackboard.com)

Canvas (canvas.instructure.com/login/canvas; free for teachers)

Nicenet (www.nicenet.org; free for teachers)

Wikis, blogs and other free virtual spaces

Wikis, blogs (web logs), vlogs (video logs) and other spaces like those provided by Facebook, Twitter, and other social media forums can also function as learning environments where students can go to practice what they learned face to face, interact with other students in different locations, or hold class meetings.

For a list of education-based wikis, try the Teaching with Thinking and Technology at https://teaching-with-technology.wikispaces.com/Wikis+in+Education

Free blogs for students can be found at edublogs (edublogs.org), kidblog (kidblog.org), and 21Classes (www.21classes.com). All of these blogs are evaluated on the Web for use in classrooms, and teachers are well-advised to check some of the advice that other teachers provide.

Students and teachers can both watch vlogs and create their own. Search “vlogs for students” or “vlogs for education” to get started.

Web page/ Web site creators

Weebly and Wix (mentioned throughout this text) and many other free web site creators are available across the Web. Unlike in the past when students had to learn to use HTML to build their site, these apps allow students to click and drag and make professional-looking pages. Each has its own strengths and weaknesses, and teachers should try the ones they are interested in before having their students use them. Crockett (2016) provides a succinct list of useful educational web site creators at https://globaldigitalcitizen.org/8-free-website-creator-tools.

Web page hosts

All of the following Web sites host personal Web space for free, although some do require registration. Instructors and students in e-learning courses can create Web pages to share their ideas and work, whether they are in different locations or in the same classroom. There are many more providers across the Web than are listed here.

Quia (www.quia.com/)

FreeSite.com (www.thefreesite.com/Free_Web_Space/)

Bravenet.com (www.bravenet.com)

Blogger (www.blogger.com)

TeacherWeb (http://teacherweb.com)

SchoolNotes (www.schoolnotes.com/)

Tripod (www.tripod.lycos.com)

Quiz and assessment tools

A large number of quiz and survey tools are available to conduct pre- and post-assessments with students both online and off. For example:

Quizstar and Rubistar (www.4teachers.org). Create quizzes and rubrics easily with these free tools.

Survey Monkey (surveymonkey.com), Doodle (doodle.com) and other free software apps can be published to the Web for all kinds of data-gathering purposes.

Video and audio conferencing tools and resources

Not typically as comprehensive as learning environments, conferencing tools allow students to meet and discuss as part of hybrid and completely online classes. For example, third graders learning about space can call a scientist at NASA for free, or middle school students in an online course can hold a videoconference with peers in Germany to compare ideas about important world problems. Usually these resources provide some combination of video, audio, and/or text capabilities, and many are free. Telephony software, or software that allows the user to make telephone calls over the Internet, is currently very popular. Examples of free conferencing and telephony software include:

MSN Messenger with Video and/or Voice (imagine-msn.com)

Yahoo Messenger (http://messenger.yahoo.com)

iChat (www.apple.com)

Skype (www.skype.com)

To learn about the benefits of videoconferencing, see https://www.eztalks.com/video-conference/benefits-of-video-conferencing-in-education.html.

Digital libraries

Students and teachers can take advantage of digital libraries in hybrid and online courses. These libraries contain everything from raw data to online texts. Examples include:

Library of Congress (https://catalog.loc.gov/)

NASA Astrophysics Data System (http://adswww.harvard.edu/)

Project Gutenberg (www.gutenberg.org/)

Visible Human Project (www.nlm.nih.gov/research/visible/visible_human.html)

Find more resources for both teacher and student use in the Teacher Toolbox that accompanies this text.

Content-based learning sites

Content-based Web sites, along with content-based stand-alone software packages, are mentioned throughout this text and can be integrated into both hybrid and online classes at all grade levels. Here are some useful sites:

National Geographic Kids’ Network (http://kids.nationalgeographic.com/)

i*earn Learning Circles (www.iearn.org/circles/lcguide/)

PBS Kids (pbskids.org)

Discovery Channel (www.discoveryeducation.com/)

Library of Congress learning page (http://lcweb2.loc.gov/ammem/ndlpedu/)

Software archives

These online storage places for software offer free or very cheap downloads for education software that can be integrated into e-learning contexts. Not all of it is the best, and teachers need to review their selections carefully.

Tucows (www.tucows.com)

WinSite (www.winsite.com)

download.com (home and education; http://download.cnet.com/s/home-and-education/?cat=education)

One of the best sources on the Internet for online learning resources is e-Learning Centre’s School e- Learning Showcase at www.e-learningcentre.co.uk/resources. Figure 8.9 summarizes some of the tools available for e-learning. Other tools are gaining popularity as e-learning flourishes.

LEARNING ACTIVITIES: e-learning

As noted throughout this book, it is not the tool that makes the difference, but how it is used. This is also true for e-learning. Throughout this text, e-learning activities such as epals, virtual field trips, ask the expert, and technology-supported communications have already been mentioned. Like other parts of this chapter, this section looks at the differences between hypothetical face-to-face (f2f) contexts and e-learning opportunities. It describes what an instructional feature or task might look like as part of an e-learning context. The features and tasks described here could be part of a hybrid or an online course. The colored text signals adaptations for e-learning.

Feature: Instructions

F2f: The teacher says, “Do exercise 5 on page 6. Ask me if you have any questions.”

e-learning: Written instructions say,

Step 1. Read the instructions for exercise 5 on page 6.

Step 2. Answer the question in no more than a paragraph using complete sentences.

Step 3. Post your answer in the Unit 1 discussion thread in the class discussion forum.

If you have questions, email your online buddy for help. This assignment is due by 3 pm on Thursday.

For e-learning, the instructions must not only be more precise, but in writing them the teacher must also try to predict what questions students might ask.

Feature: Lesson presentation

F2f: The teacher gives a lecture about creating how-to (process) essays and points out the important features.

e-learning: The instructor has students read examples from the course Web site and How Stuff Works (www.howstuffworks.com). Students then go to the online forum and discuss the important characteristics they see in process essays. Together they create a features checklist for process essays they will write.

In the online environment, this task becomes much more learner-centered.

Feature: Lesson presentation

F2f: The teacher leads a discussion based on drawings of how the Internet works from the textbook’s technology section.

e-learning: Students work in teams to complete one or more of the Peter Packet missions in Cisco’s Packetville at www.cisco.com/. (See Figure 8.10 for the introduction screen.) Using external documents such as questionnaires and graphic organizers posted to their course site by the teacher, students record important information as they discover it. They post their findings to the discussion area of the course site for other students to review.

The addition of online resources not only pushes students to be more independent learners but also addresses the needs of students with different learning preferences.

Task: Propose solutions for how to end world poverty

F2f: Students read texts about world poverty and discuss solutions with classmates.

e-learning: Through the United Nation’s Millenium Development site (www.un.org/), students work with information and people from all over the world to investigate, understand,

and work toward solutions for world poverty.

With e-learning integrated into the course, students can receive information directly from those involved in the issue, which broadens not only their audience but also their potential understanding.

Task: Prepare to study sharks

F2f: Teacher asks students to look at pictures of sharks in their text and brainstorm a list of what they understand about sharks from the photos.

e-learning: Students watch the shark videos from Nova Online at www.pbs.org/ and brainstorm a list of what they understand about sharks from the videos.

The online videos provide a more authentic glimpse of sharks and allow students to produce more language and content than the still photos from the book.

Students can learn without participating in e-learning. However, it is clear from these simple examples that, although e-learning might require more advanced planning and reassessment of important teaching skills, electronic resources and technologies can help teachers to change, in powerful ways, the focus of learning from teachers to students.

ASSESSING E-LEARNING

E-learning requires different options for assessment because, particularly in Web-based courses, the instructor cannot always observe students. Tests, quizzes, surveys, and other standard evaluations can be constructed and implemented with the tools noted above and in other chapters. However, as in traditional classrooms, these assessment tools do not provide the whole picture of student progress and achievement. Portfolios are one solution to this problem.

Overview of Portfolios

A portfolio is a purposeful, reflective collection of student work. Purposeful means that it is not a folder that contains everything students have done, but rather it is a focused compilation of student work that is developed with guidelines from both the teacher and the student. Traditional portfolios help students set learning goals, encourage students to reflect on their growth and achievement, serve as a basis for communication with parents and other stakeholders, and allow teachers to see how students are performing and plan to address gaps. There are many types of portfolios. Two common types are:

Showcase—Students display only their best work.

Developmental—Students show their progress over time.

In each case, the binding element is student reflection. Many excellent texts describe the use of portfolios to assess student progress and achievement.

e-portfolios

E-portfolios are portfolios that are kept in an electronic format (video, audio, computer-based). There are many reasons to use e-portfolios. In addition to the benefits mentioned above, e-portfolios are easy to store and access. They require students to develop multimedia skills that support the NETS standards. In addition, they can include sound, video, graphics, and photos, animation, and more, allowing students to demonstrate their learning in multiple ways.

The steps for developing e-portfolios are the same as for paper-based portfolios, except that e-portfolios require a technological aspect. The general steps that teachers and students can take are outlined below (adapted from Barrett, 2000a, 2000b; Chamberlain, 2001; Niguidula, 2002):

Identify the purpose of the portfolio. Is it to showcase students’ outstanding work, to show progress, to share with stakeholders, to demonstrate mastery, or something else?

Identify the desired learner outcomes. These should be based on national, state, or local standards and curricular requirements and include learner goals.

Identify the hardware and software resources available and the technology skills of the students and teachers. Barrett (2005) provides examples of commercial portfolio software and other tools such as PowerPoint (Microsoft) that can be used in e-portfolio development.

Identify the primary audience for the portfolio. The audience could include a college registrar, a future employer, a parent, or peers, for example. Choose a format—Web-based, CD-ROM, video—that the audience will most likely have access to. Chamberlain (2001) notes that teachers are required to obtain permission from students’ legal guardians before posting student work online. She provides sample permission letters at www.electricteacher.com.

Determine content. Teachers and students can develop a checklist of required content, including the sequencing of the information.

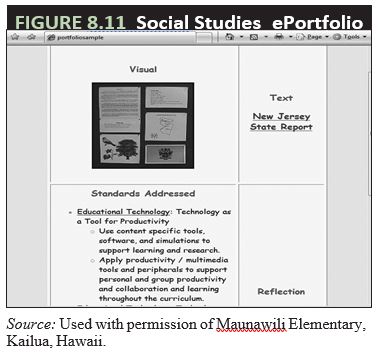

Gather, organize, and format the materials. Students should be required to include reflections on each piece and on the entire portfolio. Figure 8.11 shows a page from a sixth-grade social studies e-portfolio.

Evaluate and update as necessary. Web creators and even Microsoft Word can be used to provide templates for students to enter work samples

and other relevant material.

E-portfolios can be evaluated by rubrics that assess each step of the process (see chapter 3 for a discussion of rubrics) and that focus on meeting the standards or on other qualities deemed important, such as collaboration and participation. Other examples using a variety of tools can be found in the electronic portfolio samples section of www.forsyth.k12.ga.us/ and http://dragonnet.hkis.edu.hk/ http://wp.auburn.edu/writing/eportfolio-project/eportfolio-examples/.

Conclusion

In 2001, Bailey summed up the focus and importance of e-learning; his ideas are still pertinent:

We need to move beyond the notion that education is about school buildings, school days, and classrooms. For us to move forward with not just e-learning, but learning in general, we must accept the reality that education can now be delivered to students wherever they are located.

Schools need to become education centers. With distance education, schools become access points to a whole range of educational opportunities. Until schools recognize that their mission is fundamentally changing as a result of e-learning, we’re only going to make incremental progress toward this important objective.

Every educational program is a technology opportunity and every technology program is an educational opportunity. While our investment in technology does help schools purchase computers and networks, it is also fundamentally about purchasing math courses and additional online resources and distance education classes for their students. It isn’t about the boxes and the wires. It is about teaching and learning. It is the instructional content and its applications that should drive technology, not the other way around.

Online assessment, particularly online assessment with e-learning technologies, is one of the next generation “killer applications” that is waiting for us out there. When online assessment results are tied into e-learning systems, the potential benefits become very significant. The result should be more effective use of class time and a system of education that isn’t based on mass production, but is instead based on mass customization.

Finally, together as industry and as government, we need to be relentless in measuring and assessing the impact that technology has on education and on academic achievement. We need evidence that teaching and learning are improved as the result of technology. Using technology to teach using traditional methods will only lead to traditional results.

As better, faster, cheaper, and more accessible technologies are developed and classrooms move more toward online learning, these issues will be crucial to understand and implement. However, we must also remember the face-to-face interactions that students need and value.

FROM THE CLASSROOM

e-learning

Technology and machines have become such an integral part of our lives. There are certainly consequences—both good and bad—that are a result of this. You are probably all familiar with the many online educational classrooms/schools there are now. It just fascinates me when I go to some of their Web sites and browse through what a typical “school day” is for elementary and high school students who stay at home and learn via the computer/online courses. I think a balance is best. I can’t imagine how those student graduates of Internet schools negotiate people and peer skills. (Jennie, first-grade teacher).

It’s easier to see another angle or point of view when you don’t have those emotional cues in your face! (April, middle school teacher).

CHAPTER REVIEW

Key Points

Explain e-learning and how it can help meet learning goals.

E-learning consists of three basic components: (1) instructional and learning strategies,

(2) pedagogical models or constructs, and (3) learning technologies. e-learning contexts range from hybrid classes to those completely online and at a distance from the teacher. e-learning can help schools meet the needs of a variety of students.

Discuss guidelines for creating e-learning opportunities.

Although guidelines and tips for e-learning can also apply to f2f classrooms, they are especially crucial to follow in e-learning contexts. Teachers must work toward building a community of learners and consider what the hidden curriculum means for the students in the class. To facilitate online learning, teachers can organize ahead of time and work toward giving clear instructions.

Describe e-learning tools.

Almost any electronic tool, and many other types of tools, can be and are used as part of e-learning. The tools must, however, support and enhance student learning and not impede it.

Develop and evaluate effective technology-enhanced e-learning activities.

Features of effective e-learning activities are much the same as for those in f2f contexts, but with the added elements of technology and differences in how time is used. Activities that follow guidelines for good teaching will be effective both online and off, as long as the medium in which they are employed is considered.

Create appropriate assessments for technology-enhanced e-learning activities.

Although this book outlines many kinds of assessment that are available for e-learning, e-portfolios have many benefits for teachers, students, and other educational stakeholders.

REFERENCES

Abate, L. (2004, September 1). Blended model in the elementary classroom. tech*learning. Available: http://www.techlearning.com/story/showArticle.php?articleID=45200032.

Bailey, J. (2001, October). Keynote address presented at the Center for Internet Technology in Education (CiTE) Virtual High School Symposium, Chicago, IL.

Barrett, H. (2000a). Electronic portfolios = Multimedia development + Portfolio development: The electronic portfolio development process. Available: http://electronicportfolios.com/portfolios/EPDevProcess.html.

Barrett, H. (2000b). How to create your own electronic portfolio. Available: http://electronicportfolios.com/portfolios/howto/index.html.

Barrett, H. (2005). Alternative assessment and electronic portfolios. Available: http://electronicportfolios.com/portfolios/bookmarks.html.

Blomeyer, R. (2002). E-learning policy implications for K–12 educators and decision makers. NCREL/Learning Point Associates. Available: http://www.ncrel.org/policy/pubs/html/pivol11/apr2002d.htm.

Bowman, M. What is distributed learning? Tech Sheet 2.1. Available: http://archive.li/uBC1C

Cavanaugh, C., Barbour, M., & Clark, T. (2009, February). Research and practice in K-12 online learning: A review of open access literature. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 10(1). Available: http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/607/1182

Chamberlain, C. (2001). Creating online portfolios. Available: http://www.electricteacher.com/ online-portfolio/presteps.htm.

Clyde, L. (2004). M-learning. Teacher Librarian, 32(1), 45–46.

Conceicao, S., & Drummond, S. (2005, Fall). Online learning in secondary education: A new frontier. Educational Considerations, 33(1), 31–37.

Dabbagh, N., & Bannan-Ritland, B. (2005). Online learning: Concepts, strategies, and application. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Davis, N., & Robyler, M. (2005). Preparing teachers for the “schools that technology built”: Evaluation of a program to train teachers for virtual schooling. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 37(4), 399–409.

Giarla, A. (2017). The benefits of blended learning. teachthought. Available: http://www.teachthought.com/learning/blended-flipped-learning/the-benefits-of-blended-learning/

Jackson, R. (2004). Web learning resources, page 1 of 3. Available: http://www.knowledgeability.biz/weblearning/#CoursewareandContentPublishers.

Ko, S., & Rossen, S. (2017). Teaching online: A practical guide. New York: Routledge.

Lucas, C. (2005, July). Pod people. Edutopia, 1(5), 12.

Moore, M., & Koble, M. (1997). K–12 distance education: Learning, instruction, and teacher training. American Center for the Study of Distance Education: The Pennsylvania State University.

NEA. (2006). Guide to online high school courses. http://www.nea.org/technology/onlinecourseguide.html.

Niguidula, D. (2002). Getting started with digital portfolios. Available: http://www.essentialschools.org/ lpt/ces_docs/224.

Office of Education Technology. (2004). National education technology plan Web site. Available: http://nationaledtechplan.org/.

Setzer. J., & Greene, B. (2005, March). Distance education courses for public elementary and secondary school students: 2002–2003 (NCES 2005-010). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education.

Tallent-Runnels, J., Thomas, J., Lan, W., Cooper, S., Ahern, T., Shaw, S., et al. (2006, Spring). Teaching courses online: A review of the research. Review of Educational Research, 76(1), 93–135.

Tumulty, K., and Locke, L. (2005, August 8). Al Gore, businessman. TIME, pp. 32–34.

Zucker, A., & Kozma, R. (2003). The virtual high school: Teaching generation V. New York: Teachers College Press.

Feedback/Errata