6 Chapter 4 Supporting Students’ Critical Thinking

Critical thinking is fundamental to learner achievement in all subject areas. There are a great number and variety of standards that students are expected to meet using critical thinking skills such as analyzing, evaluating, and assessing; this is because critical thinking is essential for students to lead productive lives. Almost 30 years ago, Facione (1990) argued that critical thinking is also necessary for societies to hang together, stating, “Being a free, responsible person means being able to make rational, unconstrained choices. A person who cannot think critically, cannot make rational choices. And, those without the ability to make rational choices should not be allowed to run free, for being irresponsible, they could easily be a danger to themselves and to the rest of us” (p. 13). That sentiment is even more applicable in the age of the Internet and world unrest as humans prepare for an unknown future.

OVERVIEW OF CRITICAL THINKING AND TECHNOLOGY IN K–12 CLASSROOMS

In order to implement technology use with a learning focus, teachers need to understand critical thinking before attempting to support it with technology.

What Is Critical Thinking?

Critical thinking skills refer to abilities to be open-minded, mindful, and analytical, and to evaluate, question, reason, hypothesize, interpret, explain, and draw conclusions (Ennis, 2012). A simple way to define critical thinking is the ability to make good decisions and to clearly explain the foundation for those decisions. When using technology, being able to think critically allows one to:

Judge the credibility of sources.

Identify conclusions, reasons, and assumptions.

Judge the quality of an argument, including the acceptability of its reasons, assumptions, and evidence.

Develop and defend a position on an issue.

Ask appropriate clarifying questions.

Plan experiments and judge experimental designs.

Define terms in a way appropriate for the context.

Be open-minded.

Try to be well-informed.

Draw conclusions when warranted, but with caution. (Ennis, 1993, p. 180)

To some extent all humans, even very young children, continually think critically to analyze their world and to make sense of it. However, most people’s skills are not as well developed as they could or should be, and there is a clear link between critical thinking and student success. Scholars agree, however, that schools are not the most productive learning environments for critical thinking, and that schools need to take a stronger focus on critical thinking.

Critical thinking is part of a group of cognitive abilities and personal characteristics called higher order thinking skills (HOTS). These skills also include creative thinking (chapter 5) and problem solving (chapter 6). This list of cognitive skills is based on Bloom’s well-known Taxonomy of Educational Goals (Bloom, 1956). Bloom’s first three competencies—knowledge, comprehension, and application—are generally equated with the acquisition of declarative knowledge (discussed in chapter 2). The second three competencies—analysis, synthesis, and evaluation—are generally considered critical thinking or higher order skills. Figure 4.1 presents an example of critical thinking skills from Bloom’s taxonomy and the types of technology-enhanced tasks that might support them. Forty-five years after Bloom’s Taxonomy was published, Anderson and Krathwohl (2001) revised it to add a “metacognitive knowledge” category and to make it easier for teachers to design instruction that requires critical thinking. Excellent resources for using the revised taxonomy are available from teachthought at http://www.teachthought.com/pedagogy/50-resources-for-teaching-with-blooms-taxonomy/ and many other sources on the Web, including Pinterest (e.g., the poster at

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/287597126178595755/).

| FIGURE 4.1 Higher Order Thinking Skills from Bloom’s Taxonomy | ||

|

Competence |

Skills Demonstrated |

Sample Technology- Enhanced Tasks |

| Analysis | Seeing patterns.

Organize parts. Recognize hidden meanings. Identify components. |

Students brainstorm about the information they need and the questions they need to ask and make a chart using Inspiration software. |

| Synthesis | Use old ideas to create new ones.

Generalize from given facts. Relate knowledge from several areas. Predict, draw conclusions. |

Students gather facts from electronic and paper resources about alligators, sewers, and New York and input them into a database. They arrange and study the data to suggest conclusions. |

| Evaluation | Compare and discriminate between ideas.

Assess value of theories, presentations. Make choices based on reasoned argument. Verify value of evidence. Recognize subjectivity. |

Students evaluate their argument and conclusions about alligators in the sewers by interacting with online experts before they present their argument to the class. |

Source: From Benjamin S. Bloom, Taxonomy of educational objectives. Published by Allyn & Bacon, Boston, MA. Copyright © 1984 by Pearson Education. Adapted by permission of the publisher.

Critical thinking has been central to education since the time of Socrates (469–399 B.C.E.). The focus of the Socratic method is to question students so that they come to justify their arguments; this teaching strategy is still used in many classrooms to foster critical thinking. Edutopia (https://www.edutopia.org/) provides many resources for Socratic/ critical thinking. Critical thinking software can also provide tasks that require critical thinking and prompts to help students understand how to come to effective decisions. Regardless of the tool that students use to support their critical thinking, it is important to note the crucial role of critical thinking skills both in school and out. In fact, since Socrates, philosophers throughout history such as Plato, Francis Bacon, Rene Descartes, William Graham Sumner, and John Dewey have emphasized the need for students to think critically about their world.

More specifically, scholars note that critical thinking is one foundation for learning, in part because all of the learning skills are interdependent and, as Paul (2004a) points out, “everything essential to education supports everything else essential to education” (p. 3). For example, as students consider how to decide whether they can believe everything they read on the Internet, they use a variety of skills to

Understand basic content.

Communicate among themselves and with others.

Think creatively about resources.

Assess the veracity of the information they come in contact with.

Produce a well-supported conclusion.

In other words, they must think critically throughout the process as they develop other learning skills.

It is also clear that critical thinking is used in all areas of life as we learn and experience. Making a good decision about whether to buy a laptop or an iPod, and then which model, requires research, assessment, evaluation, and careful planning, just as deciding what to eat for dinner or how to spend free time does.

Although there may be discipline-specific skills, general critical thinking skills may apply across disciplines and content areas (Ennis, 2011a; McPeck, 1992). For example, Stupple, et al (2017) note that critical thinking skills test scores correlate positively with college GPA. Although this is not a causal relationship (in other words, the research does not show that effective critical thinking causes a high GPA), there appears to be something about students who can think critically that helps them succeed in college. In addition, the processes that students use to think critically appear to transfer or assist not only in the reading process but in general decision- making. However, experts disagree to what extent this happens. Some researchers believe that much critical thinking is subject- or genre-specific. Nonetheless, all agree that it is crucial to help students hone their critical thinking abilities, and many believe that technology can help by providing support in ways outlined throughout this chapter.

In addition to the lessons presented in this chapter based on these ideas, other chapters of this book present ideas and activities that involve critical thinking either implicitly or explicitly. As you read through the text, see if you can find those examples.

Critical Thinking and Media Literacy

Critical thinking, as defined in the previous section, is especially important because media, particularly television and computers, is increasingly prevalent in the lives of K–12 students. Students have always needed to have general information literacy, or “knowing when and why you need information, where to find it, and how to evaluate, use, and communicate it in an ethical manner” (CILIP, 2007). However, students who are faced with a bombardment of images, sounds, and text need to go beyond information literacy to interpret and assess (in other words, think critically about) information in new ways. In other words, they must be media literate.

In general, media literacy means that students are able not only to comprehend what they read, hear, and see but also to evaluate and make good decisions about what media presents. There are many variations on how to support students in becoming media literate. For example, the Center for Media Literacy, the world’s largest distributor of media education materials, recommends activities such as tracing racial images in the media throughout history, exploring how maps are constructed (and asking questions like “Why does ‘north’ mean ‘up’?”), and challenging gender stereotypes in TV comedies. These activities are crucial because learners of all ages watch TV, and even kindergartners use the computer and may have access to the Internet. Much of what learners read, see, and hear they believe verbatim and share as truth with others, particularly if someone they see as an authority posts it. This occurs whether the message is intended as fact or not. To become more media literate, teachers and students need to learn and practice critical thinking skills that are directed at the ideologies, purveyors, and purposes behind their data sources. Most important, students must use the Internet responsibly and with the necessary skepticism; in particular, this includes investigative skills and the ability to judge the validity of information from Web sites.

There are many resources to help teachers and students to become media literate. One of the best is the Center for Media Literacy’s (CML) free K-12 resources (available from http://www.medialit.org/). The site presents a clear, theory-based definition and outstanding lessons based on the five core concepts of media literacy. The lessons and handouts focus on students learning to ask these five “key questions”:

Who created this message?

What creative techniques are used to attract my attention?

How might different people understand the message differently from me?

What values, lifestyles, and points of view are represented in, or omitted from, this message?

Why is this message being sent?

Another focus of the CML is the “Essential Questions for Teachers” that teachers should ask themselves:

Am I trying to tell the students what the message is? Or am I giving them the skills to determine what THEY think the message(s) might be?

Have I let students know that I am open to accepting their interpretation, as long as it is well substantiated, or have I conveyed the message that my interpretation is the only correct view?

At the end of the lesson, are students likely to be more analytical? Or more cynical?

During media literacy lessons, students use technology to construct their own critically evaluated multimedia messages. This site is an excellent resource both for teachers just beginning to explore media literacy and for those looking for additional pedagogically sound ideas and activities.

Another outstanding source of lessons, articles, and activities for K–12 is the Critical Evaluation section of Kathy Schrock’s Web site at http://www.schrockguide.net/critical-evaluation.html), as is the useful medialiteracy.com Web site (see Figure 4.2).

Characteristics of Effective Critical Thinking Tasks

There are many ways to help students become media-literate critical thinkers. In general, effective critical thinking tasks:

Take place in an environment that supports objection, questioning, and reasoning.

Address issues that are ill-structured and may not have a simple answer.

Do not involve rote learning.

Provide alternatives in product and solution.

Allow students to make decisions and see consequences.

Are supported by tools and resources from many perspectives.

Help students examine their reasoning processes.

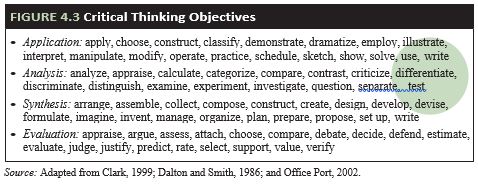

Teachers who want to promote critical thinking can employ the terms in Figure 4.3 in their student objectives and assignments. For example, if the objective is for students to analyze their use of technology, the teacher can ask students to contrast, categorize, and/or compare. If the objective is for students to evaluate technology use in schools, the teacher might ask students to defend, justify, or predict. For more information and tools for secondary school, see the resources provided by the Critical Thinking Community at http://www.criticalthinking.org/pages/high-school-teachers/807 .

Student benefits of critical thinking

It should be clear from the previous discussion that good critical thinking skills affect students in many ways. Additional benefits that accrue to good critical thinkers include:

Better grades and/or performance on high stakes tests (Watanabe, 2015)

Independence

Good decision making

The ability to effect social change

Becoming better readers, writers, speakers, and listeners

The ability to address bias and prejudice

Willingness to stick with a task

Because critical thinking skills can be learned, all students, including those with different language and physical abilities and capabilities, have the potential to reap these benefits.

THE CRITICAL THINKING PROCESS

Although all students can benefit from critical thinking, no two people use the exact same skills or processes to think critically. However, teachers can present students with a general set of steps synthesized from the research literature that can serve as a basis for critical thinking. These steps are:

Review your content understanding/clarify the problem. Compile everything you know about the topic that you are working on. Try to include even small details. Figure out what other content knowledge you need to know to help examine all sides of the question and how to get that information.

Analyze the material. Organize the material into categories or groupings by finding relationships among the pieces. Decide which aspects are the most important. Weigh all sides.

Synthesize your answers about the material. Decide why it is significant, how it can be applied, what the implications are, which ideas do not seem to fit well into the explanation that you decided on.

Evaluate your decision-making process.

Students can use this process as a foundation for discovering what works best for them to come to rational decisions. As outlined in the following section, teachers play a central role in sup- porting students in this process.

Teachers and Critical Thinking

To support the critical thinking process with technology, teachers must first understand their roles and the challenges of working with learners who are developing their critical thinking skills. These issues are discussed here.

The teacher’s role in critical thinking opportunities

Experts see the teacher’s role in critical thinking as being a model, helping students to see the need for and excitement of being able to think critically. In modeling critical thinking, teachers should:

Overtly and explicitly explain what they do and why.

Encourage students to think for themselves.

Be willing to admit and correct their own mistakes.

Be sensitive to students’ feelings, abilities, and goals and to what motivates them.

Allow students to participate in democratic processes in the classroom.

By modeling self-questioning and other strategies, teachers can help students to understand what critical thinkers do.

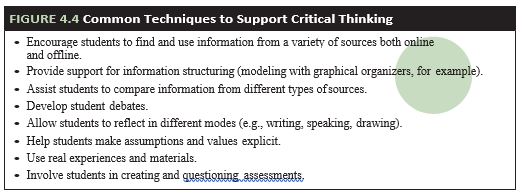

Teachers can also decide to teach critical thinking skills directly and/or through content— both are appropriate in specific contexts. Techniques that teachers can use to support critical thinking are presented in Figure 4.4. Additional ideas are listed in the Guidelines section of this chapter.

As Weiler (2004) notes, often students who are in a dualistic stage of intellectual development, in which they see everything as either right or wrong, will need a gradual introduction to the idea that not everything is so clear-cut. Rather than direct teaching of critical thinking, students can be led to understand this idea by encountering inexplicable or not easily answerable examples over time. For example, teachers addressing the urban myth of alligators in the sewers of New York might ask students to suggest what the sewers of New York might be like, and then to compare that to what they know about alligators’ natural habitats. This might lead to a thoughtful consideration of whether alligators could survive in New York sewers. The teacher’s role in this case is to ask questions to support student movement toward more complex reasoning.

Challenges for teachers

As the process above implies, learning to think critically takes time, and it requires many examples and practice across a variety of contexts. The school library media specialist is an excellent source for resources and ideas for teaching all aspects of critical thinking.

However, teaching students to think critically is not always an easy task, and it may be made more difficult by having students from cultures that do not value or promote displays of critical thinking in children in the same way as schools in the United States do or believe that it is the role of the school to do so. As many scholars point out, critical thinking in itself is probably not culturally biased, but the instruction of critical thinking can be. Teachers need to understand their students’ approaches to reasoning and objection and to teach critical thinking supported by technology in culturally responsive ways (as mentioned in chapter 2) by:

Understanding and exploring what critical thinking means in other cultures

Avoiding overgeneralizing and recognizing salient cultural features of critical thinking during the process, particularly in the tools used

Taking into consideration the strengths and differences of students

GUIDELINES FOR SUPPORTING STUDENT CRITICAL THINKING WITH TECHNOLOGY

As with all the goals outlined in this text, there are many things for teachers to think about when deciding how to support critical thinking. Many of the guidelines in other chapters also apply. The guidelines here are not specific only to critical thinking.

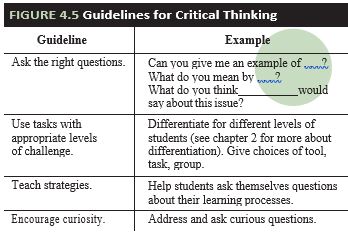

Designing Critical Thinking Opportunities

Guideline #1: Ask the right questions. Research in classrooms shows that teachers ask mostly display questions to discover whether students can repeat the information from the lesson and can explain it in their own words. However, to promote critical thinking and reasoning, students need to think about and answer “essential” questions that help them to meet universal standards for critical thinking. These standards are directly related to analysis, synthesis, and evaluation (and sometimes to application), discussed above as characteristics of effective critical thinking tasks. For example, questions about clarity (Can you give me an example of …? What do you mean by… ?) ask students to apply their learning to their experience, and vice versa. Questions that focus on precision or specificity (Exactly how much… ? On what day and at what time did … ?) ask students to analyze the data more deeply. A question about breadth (How might___ answer this question? What do you think___would say about this issue?) might also challenge students to synthesize.

Whichever set of standards or objectives teachers decide to use, it is important that the teacher support the critical thinking process by providing scaffolds, or structures and reinforcements that help guide learners toward independent critical thinking. Critical thinking does not mean negative thinking, it means voluntary, justified, educated skepticism. Question formats and strategies for creating effective questions are provided by Kentucky Prism at http://www.kyprism.org, and see Cotton (2001) for still-relevant research on questioning and strategies to make it work in classrooms. On the Web, find lists of questions that can lead to critical thinking by conducting a search on the term “critical thinking questions.”

Guideline #2: Use tasks with appropriate levels of challenge. Mihalyi Csikszentmihalyi (1997) and other researchers have found that the relationship between skills that students possess and the challenge that a task presents is important to learning. For example, they discovered that students of high ability were often bored with their lessons and that the balance of challenge and skills could be used to predict students’ attitudes toward their lessons. Their findings indicate that activities should be neither too challenging nor too easy for the student. Teachers can use observation, interview, and other assessments to determine the level of readiness for each student on specific tasks and with different content. Teachers can then use student readiness to change the challenge that students face in a task by:

Changing the way students are grouped

Introducing new technologies

Changing the types of thinking tasks

Varying the questions they ask

Altering expectations of goals that can be met

Differentiation, a strategy for designing instruction that meets diverse students’ needs (dis- cussed in chapter 2), can help teachers to provide tasks with appropriate levels of challenge for students.

Guideline #3: Teach strategies. Supporting critical thinking by modeling and asking questions is useful but not enough for all students. Good critical thinkers use metacognitive skills–in other words, they think about the process of their decision-making. The actual teaching of metacognitive strategies can have an impact on when and if students use them. To help students think about their thinking, teachers can prompt the students to ask themselves:

Did I have enough resources?

Were the resources sufficiently varied and from authorities I can trust?

Did I consider issues fairly?

Do all the data support my decision?

For English language learners (ELLs), this might mean teaching how to formulate and ask questions for clarity and specific information and to use relevant vocabulary words. One way this could hap- pen is to have ELLs create interview questions and interact with an external audience via email. Through the interaction and feedback from their email partners, the students could learn whether their questions were clear and specific and the vocabulary appropriate.

Guideline #4: Encourage curiosity. Why is the grass green? Why do I have to do geometry? Why are we at war? What are clouds made of? How do people choose what they will be when they grow up? Children ask these questions all the time, and these questions can lead to thinking critically about the world. However, in classroom settings they are often ignored, whether due to curricular, time, or other constraints. The Internet as a problem-solving and research tool (chapter 6) can contribute to teachers and learners finding answers together and evaluating those answers. However, if teachers stop learners from being curious, avoid their questions, or answer them unsatisfactorily, teachers can shut down the first step toward critical thinking.

A summary of these guidelines is presented in Figure 4.5.

CRITICAL THINKING TECHNOLOGIES

What Are Critical Thinking Tools?

Critical thinking tools are those that support the critical thinking process. Critical thinking instruction does not require the use of electronic tools. However, many of the tools mentioned throughout this book can be used to support critical thinking, depending on the specific activity. For example, word processing can help students lay out their thoughts before a debate, and concept mapping Web sites and software such as Inspiration (www.inspiration.com) can help students to brainstorm and plan their ideas. Likewise, the Internet can supply information, and databases and spreadsheets can help students organize data for more critical review.

This chapter presents tools that are specifically focused on building critical thinking skills. The following examples are categorized into:

Strategy software—content-free and structured to support critical thinking skills with student-generated content.

Content software—content is predetermined and strategy use is emphasized. Students typically read the software content and work out answers to questions.

Many other tools in these categories exist; those described here are some of the most popular, inexpensive, and useful.

Strategy Software

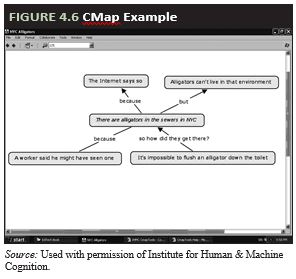

CMap v.3.8 (IHMC, 2005)

This software is easy to learn and use for third grade and up. The user double-clicks on the screen and inputs text into the shape that appears. Users can change the colors of the graphics and text to show different categories of reasoning such as objections, reasons, and claims. A very useful feature allows users to put text on the connecting lines to show the reasoning behind the connections they made. Figure 4.6 is an example map of the argument for and against alligators in the New York City sewer system. Download this software free from http://cmap.ihmc.us/.

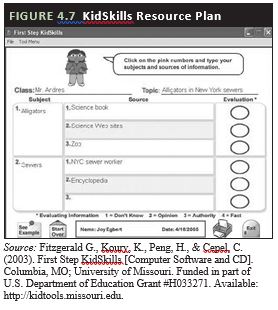

First Step KidSkills (Kid Tools Support System, 2003)

KidSkills is a free software package intended for students ages 7–13. Of the four sections, titled Getting Organized, Learning New Stuff, Doing Homework, and Doing Projects, the last has the greatest focus on critical thinking. This section has five activities: Project Planner, Getting

Information, Big Picture Card, Working Together, and Project Evaluation. Each of the activities focuses on students combining information and printing or saving it in the form of a “card” or page. In the Project Planner exercise, students make a card that lists their question, topics for them to investigate, possible re- sources, and an evaluation of the resources (authority, fact, opinion, or don’t know). There is also a Second Step available, and resources and tips for use are provided on the Kid Tools Web site. Although intended for use with learners with learning disabilities or emotional/ behavioral problems, it is useful for all children and simple enough for students with limited English proficiency to understand and use, particularly because all instructions are presented in text and audio. Some teachers may find it too simple, but its simplicity is also part of its effectiveness.

Additional apps and tools are presented in the Teacher Toolbox for this text.

Content Software

BrainCogs (Fablevision, 2002)

A CD-based strategy program, BrainCogs helps students to learn, reflect on, and use specific strategies across a variety of contexts. The software employs an imaginary rock band, the Rotten Green Peppers, to demonstrate the importance of and techniques for remembering, organizing in- formation, prioritizing, shifting perspectives, and checking for mistakes. Although the focus is more on strategies to help students pass tests, the general strategy knowledge gained can transfer across subjects and tasks because it is not embedded in any specific content area. The software is accompanied by a video, posters, and other resources that function as scaffolds for diverse learners. The exercises, in addition to being entertaining and fun, employ multimedia (sound, text, and graphics) in ways that make the content accessible to English language learners and native English speakers with diverse learning styles. Available through http://www.fablevision.com/.

Mission Critical (San Jose State University)

This Web tool provides information and quizzes on critical thinking. Although intended for college students, the quizzes are simple and well explained and could be used at a number of different grade levels with support from the teacher. The site addresses arguments, persuasion, fallacies, and many other aspects of logic and critical thinking. The site begins at http://missioncritical.royalwebhosting.net/.

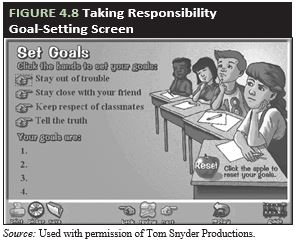

Choices, Choices: Taking Responsibility (Tom Snyder Productions/Scholastic)

Taking Responsibility helps students in grades K–4 work through a five-step critical thinking process:

Understand your situation.

Set goals.

Talk about your options.

Make a choice.

Think about the consequences.

Used on a single computer and facilitated by the teacher, the simulation in this software title provides a scenario in which two students have broken one of the teacher’s possessions; how- ever, no one else saw them. The class acts as the two students in the scenario. Through a series of decisions, the class must decide which actions to take and face the consequences of their decisions. There are 300 different ways that students can get through this software, so the consequences are not always clear- cut until they are presented to students. Figure 4.8 presents the Taking Responsibility goal-setting screen.

The software comes with many resources to help students think critically about the situations and their decisions and to assist the teacher in integrating literature, role-play, and other activities into the lesson. Each step of the simulation is presented in pictures, audio, and text, which helps ELLs and other students to access the information. The Choices, Choices series includes a number of other titles. Tom Snyder Productions/Scholastic also provides a similar Decisions, Decisions series for older students.

Teachers who want to use this type of software should be aware that the choices that students are allowed to make within the software are preset and represent the views of the software author. Teachers and students must understand the limitations and biases of this software to use it in ways that demonstrate true critical thinking.

Other Options

There are a variety of other tool options for teachers and students to support critical thinking. Brainstorming and decision-tree software, strengths/weaknesses/opportunities/threats (SWOT) analysis packages, and Web-based content and question tools are available. For more information on teaching critical thinking and how technology might help, see Schwartz (2016) and the TedEd talk “Rethinking Thinking” by Trevor Maber on ed.ted.com.

One recent trend in critical thinking is the development of school- and classroom-based makerspaces. A makerspace is a physical space that contains any array of tools and resources where students can dream, imagine, solve problems, invent, and a lot more. Makerspaces support discovery, creativity, and many of the other goals outlined in this book. For more information, see “7 Things You Should Know about Makerspaces” at https://net.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/eli7095.pdf and learn more about the maker movement at http://www.makerspaceforeducation.com/.

Additional apps and Web sites can be found in the Teacher Toolbox for this text. Whichever tools teachers decide to use, they need to remember that the tool should not create a barrier to students reaching the goal of effective critical thinking.

TECHNOLOGY-SUPPORTED LEARNING ACTIVITIES: CRITICAL THINKING

As noted previously, instruction in critical thinking can be direct through the use of explicit instruction or indirect through modeling, describing, and explaining. The goal is to help learners understand clearly why they need to think critically and to give them feedback on how they do and how they can improve. Unfortunately, few software packages and Web sites, let alone textbooks, require critical thinking skills of students. Software that does support critical thinking often requires supplementing to help students understand and use them. Teachers can supplement these resources and facilitate critical thinking during activities by developing external documents. An external document is a kind of worksheet that can involve students in, for example, taking notes, outlining, highlighting, picking out critical information, summarizing, or practicing any of the skills that support critical thinking. An external document can also enhance students’ access to critical thinking software or Web sites by providing language or content help. All kinds of external documents exist across the Internet in lesson plan databases, teacher’s guides, and other educational sites to be shared and added to.

The goal for an external document is to overcome the weaknesses of the software. An external document should:

Be based on current knowledge in the content area.

Enhance interpersonal interaction.

Provide higher order thinking tasks.

Provide different ways for students to understand and respond.

Enhance the learning that the software facilitates.

Be an integral part of the activity.

Make the information more authentic to students.

Expose students to information in a different form.

Give students more control.

Teachers can use the terms from Figure 4.3 to help plan and create external documents. Like any other tool, external documents need to be clearly explained and modeled before students use them. To make documents more accessible to students with learning challenges and/or diverse learning styles, teachers can:

Print instructions in a color different from the rest of the text.

Provide oral instructions along with the written document.

Provide visual aids when possible.

Provide slightly different documents for students at different reading or content levels.

Use large, clear print.

In this section, technology-enhanced lessons in critical thinking are supplemented by external documents to demonstrate how teachers can make do with the tools they have and also make the tools more effective. Each example provides an overview of the lesson procedure and the tools used and a sample external document that supports student critical thinking during the lesson. Specific grade levels are not mentioned, because the focus is on the principles behind the activities, and the tasks can be easily adapted for a variety of students. As you read, think about how each external document supports critical thinking and what additional documents might encourage student critical thinking in other ways.

Science Example: Shooting for the Moon

Procedure:

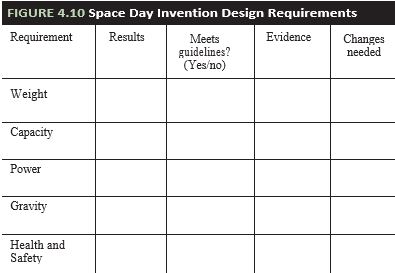

The class reads Space Day—Inventors Wanted at the about.com site (http://childparenting.about.com/). The site gives students guidelines for designing and creating an item for astronauts to take into space.

The class uses a planning tool to decide how to address this task and to make a timeline for completion.

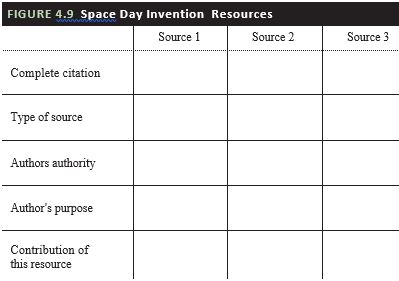

Students make teams and brainstorm their ideas in a word processing or graphics program. They list their re- sources and reasons for using each re- source in the external document, a resource handout (Figure 4.9).

After they make a preliminary decision about their invention, they use the Space Day Invention external document handout (Figure 4.10) to analyze their choices.

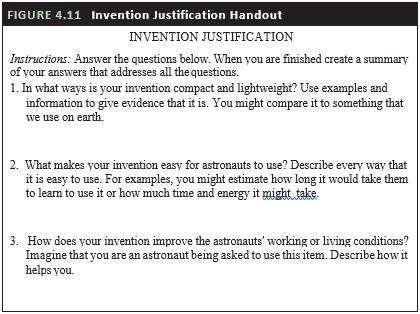

Students complete a model of their invention, then use the Invention Justification external document (Figure 4.11) to plan the written explanation that will accompany their model.

The simple external documents in this case give students a foundation for thinking, a permanent record of their thinking, and assistance for thinking, speaking, and writing about their invention. The range of documents that can be created to facilitate this activity is large; the documents can also be adapted for different students. For example, documents intended for ELLs can include graphics and vocabulary explanations, and those for students with reading barriers can be set up online and read by an electronic text reader. When students finish their project, they can be asked to review their documents to reflect on their thinking processes.

Social Studies Example: Election Year Politics Debate

Procedure:

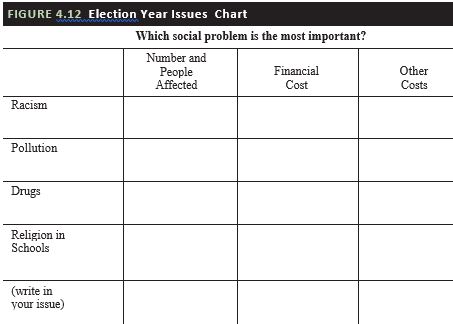

The class reads a variety of Internet sources, popular press, and opinion pieces to gather information to complete the Election Year Issues chart external document in Figure 4.12.

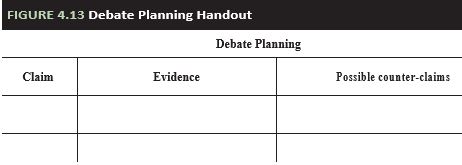

Students choose the issue they decide is most important according to the criteria given and use the Debate Planning document in Figure 4.13 to organize their position.

During the debate, students keep track of and summarize the arguments on a computer screen using a spreadsheet or other relevant software.

After the debate, students try to come to a consensus using all their documentation for support. The Issues chart helps students to focus on crucial aspects of the topic that they are thinking about. This type of grid can be used for almost any topic area. The debate planning handout is also a multiuse external document that can be employed in debate planning or discussion throughout the year in almost any subject area.

English Example: Critical Reading

Procedure:

After appropriate introduction by the teacher, students in groups of three read one of the three stories about the death of Malcolm X from Dan Kurland’s Web site (http://criticalreading.com/malcolm.htm).

Student groups complete the Reading Analysis external document (Figure 4.14), which they would have used previously for other readings.

Student groups reconfigure, with one student from each of the initial three reading groups in a new group (known as jigsaw learning). In their new groups students compare the reports and understandings from their first group and summarize their analysis of all the readings.

Students go online to discover other discussions and reports on the death of Malcolm X and to make conclusions about the events and the sources that reported them.

Instructions: Read the selection carefully. With your group, write answers to the questions. Use examples from the reading and other evidence to support your answers.

- Choose the purpose of this selection from these three choices:

- To relate facts

- To persuade with appeal to reason or emotions

- To entertain (to affect people’s emotions)

- Explain why you think this is the purpose. Use examples from the selection to support your idea.

- Why did the author write this selection?

- Where and by whom was it published?

- List all the main ideas in this selection.

- List any words that you do not know, and add a definition in your own words.

- Write a short summary of the selection. Limit your summary to five sentences.

- Decide if the information in this selection is well written. What makes you think so?

- What are the selection’s strengths and weaknesses?

- What is your group’s opinion about this selection? Does it seem fair, logical, true, effective, something else? Explain clearly why you think so and give evidence to support your ideas.

FIGURE 4.14 Reading Analysis WWorksheet

Reading is not only covered in English or language arts areas. Teachers in all subject areas need to help students evaluate sources and become more media literate, and external documents that help them to do so can be used across the curriculum.

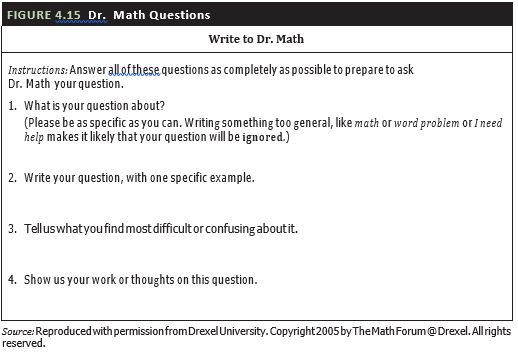

Math Example: Write to Dr. Math

Procedure:

Throughout the semester, students choose a math problem that is giving them trouble. They complete the Dr. Math Questions worksheet (Figure 4.15) about that problem. The teacher helps students post their questions to the Write to Dr. Math Web site (http://mathforum.org/dr.math/).

Students use the answer from the experts to analyze their approach to the problem and to answer a similar problem.

Presenting a problem and their thought processes to an external audience helps students clarify, detail, and explain—supporting the development of critical thinking.

Art Example: Pictures in the Media

Procedure:

Students look at the use of art in advertisements on the Web. Students choose an advertisement about a familiar product.

Examining the art that accompanies the ad, students complete the Advertising Art document (Figure 4.16).

Students choose or create new art for the advertisement based on their answers.

External documents help make the technology resources more useful, more focused, and more thought-provoking. The combination of technology tools and external documents can lead to many opportunities for critical thinking

Instructions: Look at the art in your advertisement. Carefully consider your answers to these questions.

Answer as completely as possible.

1. Describe the art objectively, including color selection, line direction, use of shadow and light, and other features. In other words, try not to use any opinion in your description.

2. In words, what do you think this picture is saying? Why do you think so? Give evidence and

examples as support.

3. Is it an accurate representation of the product? How is it related to the product? Explain your

answers clearly.

4. How do you think someone else would respond to the art in this ad? Think of several different

people you know and project what effect the art might have on them.

5. What is the purpose of this art? What do the publishers of this ad hope to accomplish? Why do

you think so?

6. What are the consequences of not knowing the influences that art can have on people?

FIGURE 4.16 Advertising Art

ASSESSING CRITICAL THINKING WITH AND THROUGH TECHNOLOGY

Evaluating student work on external documents like those described in the previous section is one way to evaluate student progress in critical thinking. Student use of strategy and other critical thinking software tools can also aid in assessment. Many of the assessment means and tools mentioned throughout this text can assist teachers in evaluating the process and outcomes of student critical thinking. Ennis (2011b) provides several purposes for assessing critical thinking:

Diagnosing students’ level of critical thinking

Giving students feedback about their skills

Motivating students to improve their skills

Informing teachers about the success of their instruction.

Although critical thinking tests do exist, Ennis recommends that teachers make their own tests because the teacher-made tests will be a better fit for students and can be more open-ended (and thereby more comprehensive). He makes a logical argument that the use of multiple-choice tests that ask students for a brief written defense of their answers might be effective and efficient.

Which is more believable? Circle one:

- The sewer worker investigates the alligators and says, “I’ve never seen one, so they don’t exist.”

- The mayor says, “Of course there are no alligators. I would know if there were.”

- A and B are equally believable.

EXPLAIN YOUR REASON:

In addition, both content and thinking skills can be tested simultaneously. For example, the question below requires students not only to answer the question but to explain their logic.

This format gives students who have credible interpretations for their answers credit for answering based on evidence. It can also eliminate some of the cultural and language differences that might otherwise interfere with a good assessment. For example, although the student might mark the multiple-choice part of the question incorrectly due to language misunderstandings or a slip of the hand, the teacher will be able to tell from the written explanation whether the student understands the question and is able to use thinking skills to think through and defend the answer. Students can complete this kind of test on the computer, avoiding problems with handwriting legibility.

Technology can aid teachers in developing tests of this sort. Test-making software abounds both from commercial publishers and nonprofit Web sites; however, few of the multiple-choice test creators also allow for short answers. An effective choice is to use a word processor to develop the test. The test can then be easily revised for future administrations. Teachers who have technical support and/or are proficient in Web page creation can also use an html editor to create a Web-based test.

Measuring critical thinking skills is not easy, but observation over time, a criterion-referenced task, and/or talk-alouds by students during activities are some ways to do so. Self-assessments can also encourage student reflection on how well they have done. Teachers can use a personal digital assistant (PDA) such as a cell phone or iPad to quickly note and store observations and, if necessary, later transfer the notes into a desktop computer for editing and sharing. Most important is to assess many situations using different methods to get the best idea of which critical-thinking skills students understand and to what degree they use them.

FROM THE CLASSROOM

Thinking Skills

There are many activities young children need to be involved in before learning the ins and outs of working a computer. A good book on this topic is Failure to Connect: How Computers Affect Our Children’s Minds and What We Can Do About It, by Jane M. Healy. All that said, computers can be extremely motivating and engaging. They can enhance our students’ use of collaborative skills and problem-solving skills. These things are very powerful in helping people learn. So while the activities you are thinking of using don’t directly match up to whatever test your students need to take, there are many computer activities that will involve many higher level thinking skills that will help our students learn, not only for THE TEST, but for life in general. (Susan, fifth-grade teacher)

Media Literacy

Learning to recognize bias in any form of media is important, especially on the Internet where anyone can publish. When are students developmentally ready to recognize bias? This is a tough question and will vary for individual students. I think that [the] use of preselected Web sites for fifth and sixth graders is a logical step. This is a good age to point out why you, as the teacher, have selected certain sites for their validity and reliability. This can be contrasted with sites that don’t meet the criteria. (Sally, fifth- and sixth-grade teacher)

Critical Thinking and Word Processing

[An article I read said that] one computer tool [that encourages students to think critically] is the word processor, because as students type, typographical, grammar or misspelled words are highlighted. Students should try to correct it themselves before looking at the suggestions by the computer. . . . this helps students become aware of their mistakes and make a conscious effort to avoid them in the future . . . I think that a conscious effort to avoid mistakes is probably going to take more than just seeing it highlighted as wrong on the computer. I think that some direct instruction or work related to those mistakes might be necessary to really help students critically think about what they did and why it wasn’t right . . . because in my experience, the computer’s tips aren’t always all that helpful. Sometimes I even wonder if spell check helps me to be a critical thinker or a carefree writer who is reliant on the computer to make corrections for me. I’m certainly not dedicated enough to try and correct my mistakes before doing a spelling and grammar check. Can we expect our students to do this? (Jennie, first-grade teacher)

Critical Thinking and the Internet

I appreciate the fact that using the Internet can promote critical thinking because the

students move from being passive learners to participants and collaborators in the creation of knowledge and meaning (Berge & Collins, 1995). The technology is empowering for students. . . They seem to feel more control over what they are able to learn and this seems to be motivating!

I wish I could figure out how to transfer that feeling to activities that are not suited for technology! (April, sixth-grade teacher)

CHAPTER REVIEW

Key Points

Define critical thinking.

There are many different lists of the specific components of critical thinking, but in general experts agree that critical thinking is the process of providing clear, effective support for decisions.

Understand the role of critical thinking in meeting other learning goals such as creativity and production.

Teachers cannot teach their students all the content that they will use in their lives. They can, however, help them to become aware of and develop tools to deal with the decisions they will have to make in school and after. Learning to think critically will help students to become better communicators, problem solvers, producers, and creators and to use information wisely.

Discuss guidelines for using technology to encourage student critical thinking. Techniques such as asking the right questions, using tasks with appropriate challenges, teaching thinking strategies, and encouraging curiosity facilitate more than critical thinking; they are good pedagogy across subjects and activities. Teachers do not need to search for tools to support critical thinking. There are plenty of free tools on the Web, and critical thinking can be supported by common tools such as word processors.

Analyze technologies that can be used to support critical thinking.

People do not often think of a word processor or spreadsheet as a critical-thinking tool, but when their use is focused on aspects of thinking, they can certainly support the process. Many electronic tools can be used to support critical thinking, but teachers must ensure that the tools do not create a barrier to students reaching the goal of effective critical thinking.

Create effective technology-enhanced tasks to support critical thinking.

Any task can have a critical thinking component if it is built into the task. Understanding how to promote critical thinking and doing so with external documents can turn ordinary technology-enhanced tasks into extraordinary student successes.

Employ technology to assess student critical thinking.

Multiple-choice tests in which students are asked to explain their reasons for their answers seem to be a logical and effective way to test not only content but thinking processes. How- ever, this is only one way to assess critical thinking. Teachers need to employ observation, student self-reflection, and other assessments over time to gain a clear understanding of what students can do and how they can improve. Technology can help teachers prepare for and perform assessments

REFERENCES

Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl, D. R. (Eds.). (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. New York: Longman.

Bloom, B. S. (Ed.). (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals: Handbook I, cognitive domain. New York: Longmans, Green.

Bransford, J., Brown, A., & Cocking, R. (Eds.). (2000). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press.

CILIP (2007). Information literacy: Definition. www.cilip.org.uk/

Clark, D. (1999). Learning domains or Bloom’s taxonomy. http://www.nwlink.com/~donclark/hrd/bloom.html.

Cotton, K. (2001). Classroom questioning. NWREL School Improvement Research Series, Close-Up #5. Available online: http://www.nwrel.org/scpd/sirs/3/cu5.html.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1997). Flow and education. NAMTA Journal, 22(2), 2–35.

Dalton, J., & Smith, D. (1986). Extending children’s special abilities: Strategies for primary classrooms, pp. 36–37. Available: www.teachers.ash.org.au/researchskills/dalton.htm.

Ellis, D. (2002). Becoming a master student (10th ed.). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

Ennis, R. (2012). Definition of Critical Thinking: Reasonable reflective thinking focused on deciding what to believe or do. Criticalthinking.net. Available: http://www.criticalthinking.net/definition.html

Ennis, R. (2011a). Why teach it? Criticalthinking.net. Available: http://www.criticalthinking.net/why.html.

Ennis, R. (2011b). Critical thinking assessment. Criticalthinking.net. Available: http://www.criticalthinking.net/testing.html

Ennis, R. (1998, March). Is critical thinking culturally biased? Teaching Philosophy, 21(1), 15–33.

Ennis, R. (2002). An outline of goals for a critical thinking curriculum and its assessment. Available:

http://faculty.ed.uiuc.edu/rhennis/outlinegoalsctcurassess3.html.

Ennis, R. H. (1992). The degree to which critical thinking is subject specific: Clarification and needed research. In S. Norris (Ed.), The generalizability of critical thinking: Multiple perspectives on an educational ideal (pp. 21–27). New York: Teachers College Press.

Facione, P. (1990). Critical thinking: A statement of expert consensus for purposes of educational assessment and instruction: “The Delphi report.” Millbrae, CA: The California Academic Press. ED 315 423.

Fowler, B. (1996). Critical thinking definitions. Critical Thinking across the Curriculum Project. Available: http://www.kcmetro.cc.mo.us/longview/ctac/definitions.htm.

Jonassen, D. (2000). Computers as mindtools for school: Engaging critical thinking. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill/Prentice Hall.

McPeck, J. (1992). Thoughts on subject specificity. In S. Norris (Ed.), The generalizability of critical thinking: Multiple perspectives on an educational ideal (pp. 198–205). New York: Teachers College Press.

Moore, T. (2004). The critical thinking debate: How general are general thinking skills? Higher Education Research and Development, 23(1), 3–18.

Office Port (2002). Bloom’s taxonomy. http://www.officeport.com/edu/blooms.htm.

Paul, R. (2004a). Critical thinking: Basic questions and answers. The critical thinking community. Dillon Beach, CA: Foundation for Critical Thinking. http://www.criticalthinking.org/aboutCT/.

Paul, R. (2004b). A draft statement of principles. The critical thinking community. Dillon Beach, CA: Foundation for Critical Thinking. Available: www.criticalthinking.org/about/nationalCouncil.shtml.

Petress, K. (2004). Critical thinking: An extended definition. Education, 124(3), 461–466.

Sarason, S. (2004). And what do YOU mean by learning? Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Schwartz, K. (2016). Three tools for teaching critical thinking and problem-solving skills. Mind/Shift: How we will learn. Available: https://ww2.kqed.org/mindshift/2016/11/06/three-tools-for-teaching-critical-thinking-and-problem-solving-skills/

Schwarz, G., & Brown, P. (Eds.). (2005). Media literacy: Transforming curriculum and teaching. The 104th yearbook of the National Society for the Study of Education, Part 1. Malden, MA:

Blackwell.

Stupple, E., Maratos, F., Elander, J., Hunt, T., Cheung, K, & Aubeeluck, A. (2017, March). Development of the Critical Thinking Toolkit (CriTT): A measure of students attitudes and beliefs about critical thinking. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 23, pp 91-100.

vanGelder, T. (2005). Teaching critical thinking: Some lessons from cognitive science. College Teaching 45(1), 1–6.

Watanabe, L. (2015). The importance of teaching critical thinking. Global Digital Citizen Foundation. Available https://globaldigitalcitizen.org/the-importance-of-teaching-critical-thinking.

Weiler, A. (2004). Information-seeking behavior in Generation Y students: Motivation, critical thinking, and learning theory. The Journal of Academic Leadership, 31(1), 46–53.

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (1998). Understanding by design. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Feedback/Errata