5 Chapter 3 Supporting Student Communication

Guidelines for every content area include communication as an essential component for meeting national standards. For example, ISTE’s national education technology standards for students (NETS*S) address student mastery of technology communication tools, including being able to “communicate complex ideas clearly and effectively” (ISTE, 2017, n.p.). The math guidelines in the Common Core Standards have a complete section on math communication that emphasizes that students, for example, “communicate precisely to others. They try to use clear definitions in discussion with others and in their own reasoning” (Common Core State Standards Initiative, 2017). Fine arts standards ask students to work together to develop improvisations; English focuses on communication skills, strategies, and applying language skills; the first goal of the foreign language and ESL standards is communication; and even PE standards support the goal of communicating about health. In every area, communication is understood to be a foundation of learning, and technology can help students to communicate with a variety of audiences for a variety of purposes by connecting them both online and off.

As you read the rest of the chapter, look for ways to use technology to help your students communicate and make connections.

Technology-supported communication projects can be fun and effective learning experiences for students and teachers, but, as this chapter will show, preparation is necessary.

OVERVIEW OF COMMUNICATION AND TECHNOLOGY IN K–12 CLASSROOMS

In keeping with the premise of this text, before discussing how technology supports communication it is important to understand what communication is and why it is an important learning goal.

What Is Communication?

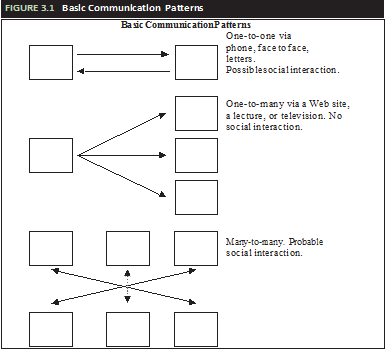

Communication is a general term that implies the conveyance of information either one-way or through an exchange with two or more partners. Shirky (2003) identified three basic communication patterns that are still used in classrooms (also shown in Figure 3.1:

Point-to-point two-way (e.g., a two-person Internet chat or a phone conversation)

One-to-many outbound (e.g., a static Web site, a lecture, a TV show, a three-way phone conversation)

Many-to-many (e.g., a group discussion)

Learning takes place when the communication is based on true social interaction. Social interaction means that the communication is two-way, but it does not mean that participants are just giving each other information. Social interaction is communication with an authentic audience that shares some of the goals of the communication. It also includes an authentic task in which the answers are generally unknown by one or more (perhaps all!) participants. This kind of interaction requires interdependence and negotiation of meaning; in other words, during their communication participants ask for clarification, argue, challenge each other, and work toward common understanding. These features of communication can lead to effective learning by assisting students in understanding information and constructing knowledge with the help of others.

Although educational software companies often advertise “interactive software,” true social interaction cannot occur with a software program because it cannot offer original, authentic, creative feedback or meet the other requirements for social interaction. Social interaction can, however, occur through technology (e.g., directly between two or more people via email, a cell phone, or other communications technology), around technology (e.g., students discussing a problem posed by a software program), or with the support of technology (e.g., teacher and students interacting about a worksheet printed from a Web site).

Social interaction, in other words, occurs between people. The interaction can be synchronous (in real time during which participants take turns, such as during a phone call, face- to-face discussion, or chat) or asynchronous (not occurring at the same time, such as in an email conversation or letters—also known as “snail mail”). There are benefits and challenges for both types. For example, during synchronous communication while texting, learners can receive instant feedback, express themselves as ideas come to mind, and learn turn-taking and other skills.

During asynchronous communication, such as an email exchange, learners have more time to think about and format what they want to say and how they want to say it. In addition, they have time to consider ideas from other participants. They also have a record of the communication that they can refer to. For both types of student interaction to be successful, participants must learn and practice skills such as listening, speaking, writing, reading, and communicating nonverbally. A list of features of social interaction is presented in Figure 3.2.

- Is two-way

- Includes an authentic audience

- Can occur through, around, or with the support of technology

- Based on negotiation of meaning

- Offers authentic, creative feedback

- Synchronous or asynchronous

- Forms the basis for cooperation and collaboration

FIGURE 3.2 Features of Social Interaction

What Is Collaboration?

One type of communication that involves two-way interaction is collaboration. Collaboration is social interaction in which participants must plan and accomplish something specific together. Power (2016) notes that “Collaboration is a coordinated, synchronous activity that is the result of a continued attempt to construct and maintain a shared conception of a problem” (n.p.). Clearly, good communication based in social interaction is central to collaboration.

What Is Cooperation?

Although both cooperation and collaboration require social interaction—and technology can support both—they are not exactly the same processes. Cooperation generally implies that students have separate roles in a structured task and pool their data to a specific end, or, as Power notes, “Cooperation is accomplished by the division of labor among participants as an activity where each person is responsible for solving a portion of the problem” (n.p.). This is clearly different from collaboration, during which students work together in different ways from the planning stage on. Both collaboration and cooperation are beneficial to student learning.

The Role of Technology in Communication

Technology, and in particular mobile technologies, can play a central role in learning through all forms of communication. For a useful overview of technology and collaboration, see Boyd (2016). In addition, research shows that students are more task-attentive and positively collaborating around and through the computer because the perceive that they have control, they receive immediate feedback, and they can collaborate with others in the “real” world (Boyd, 2016). Often, this is because the nature of the collaborative computer-based task is new, exciting, and requires different skills and language than previous tasks. It also might be because students feel that more individualized instruction and help are available. Research in these areas continues to shed light on how and why collaboration and social communication lead to learning.

In spite of what we have known about communication for years, classrooms teachers and students still often participate in a combination of the communication patterns and processes noted above—most commonly simple one-way outbound communication in the format of a lecture or presentation—but sometimes in variations of cooperative or collaborative tasks. Creating tasks in which students interact socially can be challenging, but teachers need to understand how to promote social interaction through technology-supported communication tasks in order to help students achieve. The discussion of communication tasks in the next section will assist in that challenge.

Characteristics of Effective Technology-Supported Communication Tasks

Like tasks in other chapters of this book, communication tasks span a wide range of structures and content. As noted previously, effective communication is based on social interaction. Other components of effective communication tasks include those summarized in Figure 3.3 and explained here.

| FIGURE 3.3 Components of Technology-Supported Communication Tasks | |

| Component | Focus |

| Content | Based on curricular goals and student needs. |

| Time | Appropriate for all students to finish their task. |

| Communication technologies | Help all students access the interaction. |

| Participants | Knowledgeable audience that can work with students at their level. |

| Roles | Everyone has a part to contribute. |

| Intentional focus on learning | Task and pacing help students stay on task. |

Content

The content of communication tasks and projects must be based on curricular goals and students’ needs.

Time

Time is an important element and is also based on students’ needs and on the task. Some classroom communications may take place very quickly, for example, giving instructions. Others, however, take longer, such as creating a joint bill to pass through a multi-school student congress. Typically, the more people involved and the more communication required, the more time the task may take. Also, if new technologies must be learned, time must be allotted for students to do so. In addition, students need time to think before responding in order to have the benefits of communication, and some students may need more time to formulate their communication than others.

Communication technologies

Just as work toward other learning goals can take place without electronic technologies, so can communication. However, project participants outside the classroom may not be accessible in a timely manner without the use of electronic tools such as Skype, email, oovoo and other social media apps, or the telephone. Additionally, technology can make communication more accessible to learners with different physical abilities. For example, screen readers (discussed further in the Guidelines section of this chapter) that voice the text on a computer page can help students who do not see or read well to understand the content of a communication, and dictation software can help those who cannot type well to speak their messages while the computer translates them into text.

Communication participants

There are a variety of people who can be called on to communicate with students. These include classmates and schoolmates (internal peers), peers from another school or area (external peers), parents, teachers, and content-area specialists (experts), and the general public. Lev Vygotsky (1962, 1978) and other researchers working in the sociocultural tradition show that participants are crucial to student success. These researchers posit that students learn by working through social interaction with the help of others on tasks that are slightly above their current level. Although the tasks could not be performed by the student alone, they are achievable with guidance and collaboration. Research in this area shows that what is learned with peers and others may transfer to other situations over the long term, even when students are later working individually.

Participant roles

As noted previously, communication tasks work effectively when everyone has a part to contribute to the whole. Roles can be structured and assigned by the teacher or they can be chosen less formally by students within their groups. Students can each be responsible for a certain part of the content—e.g., a different set of years in the life of a famous person—and/or a specific part of the process, such as typist, illustrator, editor, and so on.

Learning focus

Socializing, although certainly an important part of the communications process, will not help students learn content—students need to communicate about the concepts rather than just make conversation. Task structure and pacing can help students focus on the goals during tasks that require social interaction.

Student Benefits of Technology-Supported Communication

By communicating around or through technology in tasks with the characteristics listed above, students benefit in many ways. For those students who have access to relevant collaborators and technologies, benefits include

Not being limited by the school day or the school confines

Participating in individualized instruction

Feeling freer to exchange ideas openly

Being motivated to complete tasks

As they interact and negotiate meaning with others during communication tasks, students gain in language and content by

Having access to models and scaffolds

Thinking critically and creatively about language and content

Constructing meaning from joint experiences

Solving problems with information from multiple sources

Working with different points of view and different cultures

Learning to communicate in new and different ways, including using politeness tactics, appropriate turn-taking, and taking and giving constructive feedback

Working with an authentic audience

Expressing thoughts during learning

In addition, students working in teams can receive additional benefits. For example, teams tend to be better at solving problems, have a higher level of commitment, and include more people who can help implement an idea or plan. During collaboration, students learn and use communicative strategies. Moreover, teams are able to generate energy and interest in new projects. Especially important is that groups can be significantly more effective at reaching a goal than individual students would be. Because teamwork can offer students a chance to work toward their strengths supported by these scaffolds, students with all kinds of barriers to learning can benefit. The role of technology is to connect all students with a variety of audiences and interactants so that they receive the maximum benefit from their communication.

THE TECHNOLOGY-SUPPORTED COMMUNICATION PROCESS

The process of supporting communication with technology, like the content learning process described in chapter 2, includes the basic categories of planning, developing, and analysis/ evaluation.

Planning

During the planning stage, teachers should make sure that the process and outcomes are specific, relevant, and based on goals. Using objectives that state what the student will be able to do, to what extent, and in what way will assist in developing the rest of the lesson plan. For example, an objective that states, “The student will be able to describe five ways in which PCs and Macs differ” would be more effective in helping focus the lesson than a very broad objective that states, “Students should understand computers.” In addition to clear outcomes, the plan should include how and with whom students should interact. During the planning stage, teachers and students can decide whether technology is needed and if so, what kind of technology and how the chosen technology can meet the needs of students with different abilities. At this point, a review of other technology-supported communication projects might help teachers and students from forgetting something important that can make or break the activity.

During the planning stage the teacher should also find and evaluate potential participants and prepare them to understand the goals and responsibilities of the project. Many electronic lists and Web sites provide details of projects that teachers can join and allow teachers to post their own projects to find participants. iEARN (www.iearn.org) and Kidlink (www.kidlink.org) are two excellent project sites. Kidlink offers projects in many languages so that beginning English language learners can participate. Before they participate in the tasks, students should understand the writing conventions of their partners, especially if they are using a slightly different form of English (British English, for example). In addition, teachers should help students to figure out the language and content knowledge they need to grasp in order to communicate clearly and effectively during the project.

Development

The planning stage is the most crucial for creating a successful project, but the teacher’s job does not end there. It is essential during the project development and implementation stage that the teacher observes students and makes changes in the project as necessary to meet student needs and curricular goals. Providing just-in-time skills lessons and coaching on team-building are also part of this stage.

Analysis

Analysis of the project should be conducted by all participants so that different perspectives are gained. Participants should also take part in the evaluation of the task process and product. Finally, the teacher must provide appropriate closure, such as whole group discussion, a summary, or a debriefing about group process. More information on the assessment of communication projects is included in the assessment section of this chapter.

Teachers and Technology-Supported Communication

The communication process, as outlined above, can pose any number of challenges for teachers and students, but teachers can make it easier by assuming different roles and giving their students opportunities to teach themselves and others. Technology-supported communication projects can be effective vehicles for providing such opportunities, as described here.

The teacher’s role in communication projects

Teachers can take different roles in communication projects depending on the needs of their students. In some instances, for example, with younger or less-English-proficient students, the teacher may provide more help, resources, and structure and fewer truly collaborative tasks. In other projects the teacher may be more of an active facilitator in that she or he

Provides structure through choices and limits

Scaffolds and models

Provides ongoing feedback

Addresses issues that come up with lessons on grammar or other skills

Helps students to deal with any problems that arise.

Some teachers may even act as “co-learners” in the task, collaborating with their students to construct meaning during a reciprocal experience. For example, teachers and students can co-learn while using Web-based resources to answer an essential question, as described in chapter 2. Because there is no “right” answer to the task, the teacher can work with students to decide “which is best” or “how it should be done.”

Although teachers can take many roles, research shows that students are more willing to help and collaborate when the teacher is a facilitator rather than a guide or an all-knowing sage (see an explanation by Jones, 2015). Kumpulainen and Wray (2002) outlined four effective roles for the teacher in any project. These are shown in Figure 3.4.

The most important role for teachers in communication projects is to understand what their students need and to help them to meet the challenges of the task.

- The teacher encourages students to share and initiate.

- The teacher scaffolds and strategizes with students.

- The teacher assists in shaping the rules that help everyone participate and understand different perspectives.

- The teacher paces the task according to student needs and acts as a member of the learning community.

FIGURE 3.4 Roles for Teachers

Challenges for teachers

Potential challenges for teachers and students in completing communications projects include:

Dealing with technical difficulties and non-responses from participants

Planning around school breaks

Making sure the distant partners understand the goals and procedures

Handling inappropriate message content

Providing just-in-time feedback and scaffolding

Group dynamics, or how people interact in a group, might also be an issue that teachers and students must deal with, regardless of the type of interaction. A number of research studies point out that students’ social status and other characteristics of group members might lead to breakdowns in participation and collaboration. The guidelines discussed in the next section suggest ways to overcome these barriers.

The more technology, distance, and participants involved in a communication project, the more challenges participants face in keeping the project going and making it an effective learning experience. That does not mean, however, that it is not worth the effort, but rather that careful planning and flexibility are necessary.

GUIDELINES FOR SUPPORTING COMMUNICATION WITH TECHNOLOGY

Designing Technology-Supported Communication Opportunities

Planning is crucial for the success of any communication project, regardless of how and whether it uses technology. Teachers must choose participants carefully, matched the project to standards and curriculum, and develop scaffolds to help students succeed. Two other useful guidelines for planning include considering the context and making safety a primary focus.

Guideline #1: Consider the context. Among the many resources communication tasks can employ, he has decided to use Google Docs as the most efficient way to give his students time to work on the project. Docs is a Web-based word processor to which teachers can control access and that they can set up to meet the needs of their specific students. Students can cooperate and collaborate with their teams and teacher from wherever they may be.

Teachers do have other choices of tools, but they should choose the most efficient for their physical contexts. In classrooms or schools that do not have reliable Internet access, participants still can access collaborators in other ways, such as through fax, phone, or letters, depending on the project timeline and the suitability of the technology to the project. If a classroom has only one computer, a project that is computer intensive for all students probably would not be efficient or effective.

Guideline #2: Safety first. Having children on the Internet is fraught with possible dangers, from accessing inappropriate Web sites to providing access to themselves; given only a child’s name and general location, anyone can search the Web and obtain a map to the child’s home. (For current statistics on Internet dangers and ideas about how to avoid them, see the excellent Enough is Enough site at http://enough.org/). Three aspects of safety must be considered to ensure that students are not harmed during communication and collaboration projects.

Classroom and school safety policy. Many schools and districts have a safe use policy for the technology in their school. Students and parents must read and understand the issues and deal with them swiftly if the rules are broken. Teachers can model their rules on the “Rules for Online Safety” from the Safekids site (safekids.com). These rules for students include:

Never give out personal information or passwords, or send a picture without permission.

Tell adults if they come across information that makes them uncomfortable.

Do not meet online buddies without permission and a chaperone.

Do not respond to mean or uncomfortable messages.

Make rules with parents for going online.

Do not download anything without permission.

not hurt others or break the law.

Teach parents about the Internet.

Samples of other acceptable use policies are provided by the Family Online Safety Institute at https://www.fosi.org/.

Safe contexts. There are two issues in providing a safe context—with whom students interact and about what. This aspect is easier to control in face-to-face communication projects, but even within the classroom students can be subjected to harassment, inappropriate interaction, and other types of harm. Teachers should choose participants with whom they are familiar and whom they have evaluated carefully as being able to carry out the project within the boundaries set.

Safe tools. The Internet can be a scary place, and open-ended software and access are fraught with financial, privacy, legal, and other potential problems. Sites like Gaggle.net minimizes risks to students by providing Web-based email access focused on classroom use. It filters all messages and provides access to a variety of administrators and other participants, and it includes message boards that are monitored for content and chat rooms just for the school. The teacher can review all messages, and the system sends the teacher messages that might have inappropriate content. In addition, teachers can develop a list of inappropriate words that the software monitors. Teachers have the power to deny student access to their account and can block spam, or unsolicited, unwanted, or inappropriate messages, from external domains. Other safe tools include Kidmail (kidmail.net), www.epals.com, and other emailing options and filtering software such as NetNanny (http://www.netnanny.com/), that teachers can use, for example, to access and control what comes in and out of students’ email boxes (when they use these tools only, however).

Guideline #3: Teach group dynamics and team building skills. When students work face-to-face around or with the support of the computer they can use pragmatic cues such as facial expressions and gestures to help with understanding. It is sometimes difficult for students to work well in teams even when they do have these cues. When students work through the computer without video support, these cues are absent, and therefore meaning has to rely solely on text. Lack of pragmatic cues can lead to miscommunication, misunderstanding, or worse, particularly if students from diverse backgrounds are participating. Therefore, students in all contexts need to develop or reflect on team building and group dynamics skills. In addition to clearly communicating the process and product expectations to students, teachers can help them learn to understand and work within groups by making sure that they can:

State their views clearly, and provide constructive criticism

Take criticism, intended or unintended.

Define their roles.

Deal with dissent; ask about miscommunications or misunderstandings (conflict resolution).

Use appropriate levels of politeness and language.

Develop an effective self-evaluation process.

Scenarios, modeling, and role-plays can be effective tools for developing these skills.

Guideline #4: Provide students with a reason to listen. Teaching students to listen actively to each other is no easy task. However, if they do not develop this skill, time on task is lessened and learning is less successful. Often teachers assume that students will listen because they are expected to, but this does not always happen. A great project that does not require students to listen to each other wastes some of the most effective learning opportunities. For example, a group presentation aimed solely at getting a grade from the teacher typically isolates the rest of the class from the knowledge being presented, especially if the topic of the presentation is the same for the group before and the group after. Likewise, chats, online discussions, or even emails that are too long, too unstructured, or in which it is difficult to find the relevant information can also allow students not to listen. Students are more likely to listen actively if they have a good reason to do so, and project structures can give that reason. For example, teachers can provide “listening” handouts on which students have to record some of the information for future use, or the teacher can assign students the role of presentation evaluator. In addition, authentic tasks in which outcomes are not all the same help students to listen. Figure 3.5 presents a summary of these guidelines.

| FIGURE 3.5 Guidelines for Designing Opportunities for Communication | |

| Guidelines | Explanation |

| Consider the context. | Use technologies that work with the students, audience, and task. |

| Make safety a primary focus. | Review the classroom and school safety policies.

Choose safe technologies and a safe audience. Work with parents. |

| Teach group dynamics and team-building skills. | Help students understand how to work effectively in groups with people of all kinds. |

| Provide students with a reason to listen. | Provide opportunities for students to listen actively for important information.

Make the information crucial to their success. |

COMMUNICATION TECHNOLOGIES

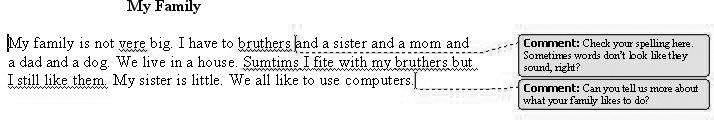

Guidelines like those above are useful for developing communication tasks, but the right tool is essential. Egbert (2005) notes, “Many educators believe that technology’s capability to support communication and collaboration has changed the classroom more than any of its other capabilities. In fact, it is how educators make use of that capability that can change classroom goals, dynamics, turn-taking, interactions, audiences, atmosphere, and feedback and create a host of other learning opportunities” (pp. 53–54). One crucial aspect of effective use is a tool that fits the tasks that they are requiring of their students. There can be many such tools, from MS Word’s commenting feature, with which the teacher and peers can communicate about a student’s writing, to Voicethread (voicethread.com/) and Jing (www.techsmith.com/jing.html), through which teachers and students can communicate both in text and orally.

FIGURE 3.6 MS Word Commenting

FIGURE 3.6 MS Word Commenting

FIGURE 3.6 MS Word Commenting

The rapid growth in communication using digital support, particularly Facebook, Reddit, and other popular social media platforms, attests not only to the value of social connections, but also to the importance of those connections to life and learning. Wikis and weblogs are currently some of the more often-used classroom tools in social software, but often the older (and sometimes simpler) tools such as digital tape recorders and basic email can provide what teachers and students need, and these tools can be more accessible to a variety of users. For example, Sound Recorder software is included in every Microsoft operating system and Voice Memo is included with the Mac OS. However, as teachers understand more about the affordances, including privacy features and accessibility, that they can use in apps such as Facebook and Yahoo Groups, these apps may become more common for school use. Two-way interactive video and other communication technologies that are also used frequently for distance education or eLearning are described in chapter 8. Other tools are listed in this text’s Teacher Toolbox.

Some communication tools are free (called freeware; this includes Google Docs); others are shareware. Shareware is software that users can test, and if they decide to keep it they pay a small fee to the developer. Typically, freeware and shareware are created by individuals or small groups of developers. Other tools for communication are commercial products sold by software companies. They vary in how easy they are to use and what they can do. Commercial products are usually more sophisticated and have many more features, but that does not always make them better for classroom use. As with any tool, teachers should check them carefully for characteristics that support effective and/or efficient learning before adopting them for classroom use.

Most teachers probably think of telecommunication tools as those mentioned previously, but software packages can both directly and indirectly support communication. Even common software packages such as word processors can be used for collaboration; as noted in chapter 2 and above, the “comment” function in Microsoft Word allows learners to comment on one an- other’s work in writing inside the document. Voice (oral) annotations are also possible and are a good alternative for students who do not type well, who have physical barriers, or whose written skills are not understandable.

In addition, much of the software from educational software companies such as Tom Snyder Productions/Scholastic (www.tomsnyder.com) is based on student collaboration. Packages such as the Inspirer (geography/social studies), Decisions, Decisions (government/social studies), and Fizz and Martina (math) series are aligned with content-area standards and have built-in mechanisms for collaboration. The teachers’ guides that accompany these software packages also include ideas about how to make the collaboration work for all learners, including English language learners. Perhaps essential for some contexts, much of the Tom Snyder software is intended for students to work with as a class in the one-computer classroom. However, more important than how the software connects learners is why and with whom learners connect. Much content-based software guides students into predetermined conclusions, and teachers must take care to make sure that those conclusions are equitable and socially responsible.

LEARNING ACTIVITIES: COMMUNICATION TASKS

Communication opportunities are mentioned throughout this book because learning results from the interaction that takes place during these opportunities, regardless of the task goal. Many of the activities in this book have a communication component. Although examples of telecommunications projects abound, there are fewer examples of communication projects in which students work around and with the support of technologies. However, in addition to the tools listed previously, Web sites and other Internet tools provide an amazing number and variety of opportunities for students to communicate around, with, and through technology.

This section presents examples of communication activities. Each of the examples described begins with a content-area standard as its goal. All examples also address the technology standard that students learn to communicate effectively with and to a variety of audiences. Audiences for the examples are included; an internal peer refers to a classmate or schoolmate, and an external peer is someone in another school, district, region, or country. Teachers are not included as participants in these examples because it is a given that much classroom communication will be aimed at or filtered through them.

In the activities, students work around, with the support of, and through the computer. As you read the activities, reflect on how the guidelines from this chapter might be applied in each case and which technologies might be used to support the learning opportunities.

| Standard: Science—Students develop understanding of organisms and environments. | |

| Participants | Activity |

| Internal peers | Work together to build an electronic text on animal habitats. Present the text to students in other grade groups to help them prepare for a test. |

| External peers | Complete a series of science mysteries using the format that Mr. Finley developed. Use mystery animals from another region of the world as the subjects of the project. |

| Experts | Complete a habitat WebQuest (search at webquest.org) and then have the products evaluated by local scientists or zoo personnel. |

| General public | Prepare the lesson on animal habitats located at http://school.discovery.com/lessonplans/programs/habitats/. Develop the Mystery Animals extension of the lesson and post the mysteries to the Web for others to guess. |

Science Example: Mad Sci (http://www.madsci.org/)

In addition to features such as links, lessons, “random knowledge,” the Visible Human tour, and lots of fun experiments, the Mad Sci site provides Ask-a-Scientist (http://www.madsci.org/submit.html). Be sure that students understand the rules of use, published clearly on the site, before they pose questions to the experts. Students should also learn how to write succinct, pointed questions that experts can answer in a short amount of time. The people who run the site and its policies and procedures are clearly stated, making it easy for teachers to decide whether this is a safe site and how it can best be used. Use the information in “Setting Up an Ask the Expert Service” to create your own expert site; this might be a particularly useful experience for secondary students in specific disciplines.

| Standard: Social studies—Work together to promote the values and principles of American democracy. | |

| Participants | Activity |

| Internal peers

External peers Experts General public |

Work with internal peer teams using a worksheet and Web site

to find out more about local democracy. Take one political organization or body (who serve as experts) to interview, or each team member can gather information on one aspect of each organization, by email, telephone, or face to face. Then create a report to share with the rest of the class. Build posters to hang in town so that the general public is also informed. Work with external peers to compare and contrast community decision-makers across states, regions, and countries. |

Social Studies Example: Voices of Youth (http://www.unicef.org/voy/)

Current discussions (2017) on this site supported by UNICEF include “The Hidden Victims of the Migration Crisis,” Where Do I Belong,” and “Young Bosses?,” posted by students from around the world and available for discussion both on the site and through Twitter.

| Standard: Math—Organize and consolidate mathematical thinking through communication. Communicate thinking coherently and clearly to peers, teachers, and others. | |

| Participants | Activity |

| Internal peers | Collaborate in groups around one computer as the teacher facilitates Fizz and Martina’s Math Adventure (Tom Snyder Productions/Scholastic). Communicate answers and understandings as the work progresses. |

| External peers | Work on a math activity, such as The Cylinder Problem, at http://mathforum.org/brap/wrap/elemlesson.html. Email understandings and questions to peers who are also studying this problem. Together, the groups come to solutions and conclusions. |

| Experts | Work with family members to perform the same calculations. Use the Family Math Activity provided by Math Forum at http://mathforum.org/brap/wrap/familymath.html. |

| General public | Write word problems and challenge members of the public to solve them, through email, a Web site, or public mail. |

Math Example: The Globe Program Student Investigations (http://www.globe.gov/)

At this site, teachers and their students can join any number of collaborative student investigations with peers from around the world, submit reports and photos of their projects, and discover information from other projects.

Additional Examples

| Standard: English—Students adjust their use of spoken, written, and visual language to communicate effectively with a variety of audiences for different purposes. | |

| Participants | Activity |

| Internal peers External peers Experts General public | Write a persuasive essay collaboratively. Share the essay with internal and external peers for feedback and get help with content from experts during the process. Publish a hard copy of the paper at the school or a digital copy in an electronic forum for public consumption and response. |

| Standard: Physical Education—Demonstrate the ability to influence and support others in making positive health choices. | |

| Participants | Activity |

| Internal peers | Create and present a multimedia presentation for younger students about some aspect of health and fitness. |

| External peers | Through email, build an argument that uses online and offline resources to convince peers to try your favorite healthy recipe. |

| Experts (doctors) | Check WebMD.com or other sites for advice or information about a health issue and then discuss any questions, especially about the answers you found, on Ask a Doctor at http://www.mdadvice.com/ask/ask.htm. Use the findings to create a persuasive essay or letter to the editor. |

| General public | Develop Web pages that provide feedback about healthy eating, or create a survey that provides results about how healthy a particular diet is. |

| Standard: ESL—Use English to participate in social interaction. | |

| Participants | Activity |

| Internal peers | Work on a project using Tom Snyder Productions/Scholastic’s Cultural Reporter books and templates. Conduct interviews, library research, and use other resources to find answers to a question about American culture. |

| External peers | Use computer-mediated communication to meet and converse with peers from around the world. |

| Experts | Go to Dave’s ESL Café (http://www.eslcafe.com/) to ask questions about grammar and other language and culture issues. |

| General public | Create an electronic forum using Blogger or another platform to discuss idioms, jargon, and colloquial speech from all over the United States. Ask follow-up questions to contributors and thank them for their participation. |

Multidisciplinary Example: iEARN (http://www.iearn.org/)

One of the most popular sites on the Web for “collaborative educational projects that both enhance learning and make a difference in the world,” the International Education and Resource Network (I*EARN) provides three different types of opportunities for students and schools—to join an existing project, to develop a project relevant to their curriculum, or to join a learning circle. Projects span content and skill areas and include students from countries around the world. Projects on topics from folktales to funny videos and values to sports incorporate every subject area and result in a product or exhibition that is shared with others.

Communicating in Limited Technology Contexts

Benefits of using the kinds of ready-made projects provided by I*EARN, described above, include the support that is available, such as tips for helping participants understand each other, software that is accessible for learners with slow Internet access, and offline work for students in limited technology contexts.

Of course, there are classrooms around the world that do not have access and cannot participate in the electronic portion of these amazing technology-enhanced projects. That does not mean that they are not valuable as interactants. Teachers and students need to reflect on how to communicate and collaborate with peers regardless of their access to digital technologies.

Other Communication Projects

Some particularly powerful learning experiences based on communicating come from follow-alongs, in which classes interact with experts and adventurers around the world as they travel through space, bicycle around the world, compete in the Iditarod, or make discoveries along the Amazon River. For examples of these and other communication projects, teachers can conduct a Web search with the terms “student examples” and “telecommunications projects.” This search will provide more responses than it is possible to review. To make the search more useful, add a content area, grade level, and other details to the search. Teachers do not necessarily need to develop projects from the ground up—there are plenty of project frameworks and examples for teachers to join or use in developing their own. Of course, teachers should give credit to the originator of the lesson or project and modify it to fit their specific contexts.

ASSESSING COMMUNICATION TASKS: RUBRICS

The wide variety of communication activities noted in the previous section, along with the diversity in student skills, goals, and needs in every classroom, indicate that student achievement during communication tasks should be assessed at different times in different ways. This section describes ways to assess student process and outcomes during communication tasks. Other assessments throughout this text may also be applicable to the assessment of communication tasks— as you read other chapters, keep this in mind.

Planning

In the planning stage, teachers can check on the effectiveness of the project design using the Lesson Analysis and Adaptation Worksheet (found in the Teacher Toolbox).

Development

During the project, teachers can use formative assessment tools, or tools that help students understand their process and provide feedback to help them work better. Formative assessments include teacher observations. Teachers can make observations using personal digital assistants or other portable technologies in conjunction with checklists like the inclusion checklists from http://www.circleofinclusion.org/ or a teacher-made checklist that notes student progress toward individual goals. Student self-reports—for example, “a list of what I accomplished today” or “a question that came up today”—can also help to make sure that students are on task and that the project is moving toward the goals effectively.

Analysis

To make a summative evaluation, in other words, to assess outcomes or products, it is important to strike a balance between team outcomes and individual accountability. Peer assessments, based on team participation or progress, are often useful for evaluating individual performance, and if the project consists of online segments, teachers can collect copies of the discussion and other participation examples. Another option for peers is to keep an “I did/he did/she did” list (McNinch, personal communication, 2005). Students list what each team member contributed to the project. The teacher can cross-reference the lists and observations and have a pretty good idea of what was done by whom and perhaps even what affected the group dynamics.

Rubrics are also useful to assess product and process. A rubric provides both criteria for evaluation and the performance levels that should be met. Rubrics also help students to understand what is expected of them throughout the project. Teachers can find many free rubric-makers and sample rubrics on the Web. Some guide the teacher through the whole rubric construction process (e.g., Rubistar, rubistar.4teachers.org/), and others supply different rubrics for different types of tasks (e.g., Teachnology, teachnology.com/web_tools/rubrics/).Even if teachers and students use these technologies, they still need to understand how and why to create assessment rubrics. Prentice Hall School Professional Development’s Web site (www.phschool.com/) sums up the following guidelines for rubric development:

Specify student behaviors that you will observe and judge in the performance assessment.

Identify dimensions of the key behaviors to be assessed. If the assessment tasks are complex, several dimensions of behaviors may have to be assessed.

Develop concrete examples of the behaviors that you will assess.

Decide what type of rubric will be used: one that evaluates the overall project, one that evaluates each piece of the project separately, a generic rubric that fits with any task, one created specifically for this task, or a combination.

Decide what kind of outcomes you will provide to students: checklists, points, comments, or some combination.

Develop standards of excellence, or criteria, for specified performance levels.

Decide who will score each performance assessment—the teacher, the students (either self-scoring or peer scoring), or an outside expert.

Share scoring specifications with other stakeholders in the assessment system—parents, teachers, and students. All stakeholders must understand the behaviors in the same way.

Rubrics are best understood by students when they have a hand in making them. Regardless of who makes the rubric, students must be able to access the criteria and have clear examples of performance levels throughout the project. For example, if a teacher provides handouts and mini-lessons during a project, that teacher can use both the completed handouts and observations to give students feedback on their progress. To measure the outcomes, the teacher can develop a rubric with his students based on the objectives of the project. They will decide together that the important criteria for the project. The teacher can then work with the students to clarify each level of performance (excellent, good, fair, poor) and to help them use the rubric to assess their own performance.

If students are safe and well prepared, communication around, through, and about computers can help them to achieve in a variety of ways. It can also support 21st-century skills such as critical thinking, the topic of chapter 4.

FROM THE CLASSROOM

Classroom Interaction

Students involved in group projects will have a positive experience with writing, reading, and speaking English when the emphasis is placed on the group versus on the individual. Students practice reading, writing, and speaking English through brainstorming of ideas. Through peer editing and revising students are involved in using/learning language. Using technology to locate information and publish group activities encourages careful use of reading strategies, following directions, creative thinking to solve problems, and respect and constructive behavior to accomplish a task. As the classroom setting becomes a group of students accustomed to sharing common interests and pursuits, mutual respect, trust, acceptance, responsibility, and self-evaluation will be fostered. These are lifelong skills needed to function productively in any society. (Jean sixth-grade teacher).

While I think that cooperative learning has its place, I am not that enthralled with it. I disagree with always giving kids a specific job to do in a group activity. I think the student learns more from collaborative learning, when he or she is involved with the whole process. I like the idea better of all members sharing ideas to accomplish a task. I don’t think all members of a cooperative learning team learn as much as they could because they are limited by their specific tasks. For example, how much learning does the timekeeper really get out of an activity when all he or she is doing is just keeping track of the time? Sure the timekeeper watches, but the timekeeper could be watching a demonstration in the front of the room and learn from observing. I think we want our kids to be actively involved. We want each one of them to be using as many senses as possible when learning. When we purposefully limit them to using only a few senses, I think we are shortchanging them. Collaborative learning, on the other hand, requires all students to be active participants in the learning. Students share in the total experience, and I feel much more learning can take place. I am not saying that cooperative learning does not have any place in the classroom. I think there are times when what we want to teach is accomplishing a task with each member of the group helping with just one role. In those cases I think cooperative learning is great. For the most part, however, my vote would be with collaborative learning. (Susan, fifth-grade teacher).

Safety

Our students have to get a form signed by their parents allowing them to use the Internet. It also acts as a contract stating that the student will follow the school guidelines on Internet use. Furthermore, their core teacher has to sign the form, agreeing with the students and the parent that the student will use the internet for appropriate, scholastic reasons. So, in order for the student to have Internet use, not only does the parent have to sign the form but the student and the teacher as well. (Adrian, sixth-grade teacher)

Follow-Along

Last year I participated with my class in a wonderful Web-based project where a group of teachers registered as part of Iditarod. We shared general information about our classes: age, demographic, geographic location, etc. This information was posted in a list-serv. There were suggested activities and opportunities for classes to interact with one another as we researched the history of the Iditarod and followed the race itself in March. Each of my table groups picked a musher to follow through the race. They emailed the musher—all but one group received personal email responses from the musher. There are tons of resources that accompany the project, some submitted by teachers, others by the Web master. It connected the kids with real action following the daily postings of the Iditarod race. (Jennie, first-grade teacher).

CHAPTER REVIEW

Key Points

Define communication, collaboration, and related terms.

The boundaries between communication, interaction, cooperation, and collaboration can be blurry. In the simplest sense, “communication” can be seen as the umbrella term. Communication can be one-way or two-way. Communication includes interaction, meaning give-and-take between participants. Interaction can be cooperative or collaborative, both of which require negotiation of meaning. Interaction can also be asynchronous or synchro- nous. Both types of interaction have advantages and disadvantages.

Describe the communication process and explain how communication affects learning.

The communication process includes planning, developing, and analysis/evaluation. Each step is important for communication tasks to be effective. This chapter has described the importance of social interaction to learning. Social interaction provides scaffolds for language and content, which help move students to new understandings. Benefits include exposure to new cultures, language uses, views of content, and the use of critical thinking skills.

Discuss guidelines and techniques for creating opportunities for technology-supported communication and collaboration.

Choosing the best technology for the task and making sure that students are safe while using the chosen tools are paramount objectives for successful projects. Most important for such projects is that tools can be used to facilitate the language and content acquisition of all students, from differently abled to differently motivated. In addition, teaching group dynamics and team building skills and giving students reasons to listen help avoid communication breakdowns during projects that rely on communication. Fair, useful, and ongoing assessment facilitates students’ understanding of their roles, their progress, and the effective- ness of the project. Careful planning that includes these strategies can support effective learning experiences.

Analyze technologies that can be used to support communication, including MOOs, email, chat, blogs, and wikis, Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, WhatsApp, Google Hangouts.

People probably think of communication tools as technologies that students can use to connect through. However, students can also connect around and with the support of technologies such as stand-alone software and Web sites. The technology must be appropriate for the goal, support the intended communication, and be accessible to all participants.

Describe and develop effective technology-enhanced communication activities.

Teachers can work with students to provide learning experiences that address the needs of a wide range of learners while addressing standards and curricular requirements by:

Using the planning, development, and evaluation processes outlined in the chapter

Keeping in mind student needs and the physical context

Focusing on crucial language and content goals

This chapter’s activity examples provide only a small sample of a very large set of interesting and fun projects that involve communication around, supported by, and through technology. The true scope of projects that include some kind of communication is beyond the ability of this book to address. Teachers can use existing resources and their own (and their students’) knowledge and imagination in developing relevant tasks that achieve learning goals.

Create appropriate assessments for technology-enhanced communication tasks.

A wide range of tools is available for teachers to use in assessment. One tool that can help in a variety of contexts is a rubric-maker. In addition, ready-made rubrics and checklists are available across the Web. Understanding how to develop and use rubrics is an important step in creating appropriate assessments.

REFERENCES

Berger, C., & Burgoon, M. (Eds.). (1995). Communication and social influence processes. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press.

Boyd, N. (2016). Collaboration via technology as a means for social and cognitive development within the K-12 classroom. In D. Mentor (Ed.), Handbook of Research on Mobile Learning in Contemporary Classrooms (Chapter 9). Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

Cesar, M. (1998). Social interaction and mathematics learning. Nottingham, England:

Centre for the Study of Mathematics Education: http://www.nottingham.ac.uk/csme/meas/papers/cesar.html.

Coleman, D. (2002, March). Levels of collaboration. Collaborative strategies. San Francisco, CA: Collaborative Strategies. http://www.collaborate.com/ publication/newsletter/publications_newsletter_march02.html.

Common Core State Standards Initiative, 2017. Standards for Mathematical Practice. Available : http://www.corestandards.org/Math/Practice/#CCSS.Math.Practice.MP5.

Egbert, J. (2005). CALL Essentials: Principles and practice in CALL classrooms. Alexandria, VA: TESOL.

Eisenberg, M. (1992). Networking: K-12. ERIC Digest ED354903. Retrieved 2/19/05 from http://www.ericdigests.org/1993/k-12.htm.

Harris, J. (1995). Organizing and facilitating telecollaborative projects. The Computing Teacher, 22(5), 66–69.

Hofmann, J. (2003). Creating collaboration. Learning circuits. Alexandria, VA: American Society for Training and Development. http:// www.learningcircuits.org/2003/sep2003/hofmann.htm.

ISTE, 2017. ISTE standards for students. Available https://www.iste.org/standards/standards/for-students.

Jones, D. (2015). Guide on the side(lines). Edutopia. Available: https://www.edutopia.org/discussion/guide-sidelines.

Kumpulainen, K., & Wray, D. (Eds.). (2002). Classroom interaction and social learning: From theory to practice. New York: RoutledgeFalmer.

Panitz, T. (1996). A definition of collaborative vs. cooperative learning. Deliberations on Learning and Teaching in Higher Education. London, England: Educational and Development Unit, London Guildhall University. http://www.city.londonmet.ac.uk/deliberations/ collab.learning/panitz2.html.

Power, L. (2016). Collaboration vs. cooperation: There is a difference. The Blog. Available: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/lynn-power/collaboration-vs-cooperat_b_10324418.html

Shirky, C. (2003, April). A group is its own worst enemy. Presented at the O’Reilly Emerging Technology conference in Santa Clara, CA. Retrieved 2/20/05 from the World Wide Web: http:// www.shirky.com/writings/group_enemy.html.

Svensson, A. (2000). Computers in school: Socially isolating or a tool to promote collaboration? Journal of Educational Computing Research, 22(4), 437–453.

2Learn.ca Education Society. (2005). Explore or join projects@2Learn.ca. Retrieved 2/19/05 from www.2learn.ca/Projects/projectcentre/exjoproj.html.

Vygotsky, L. (1962). Thought and language. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Vygotsky, L. (1978). Mind in society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Feedback/Errata