Module Overview

As we have seen, to change behavior, we must know what the behavior is that we want to change, whether it is going to the gym more often, removing disturbing thoughts, dealing with excessive anxiety, quitting smoking, preventing self-injurious behavior, helping a child to focus more in class, taking our dog for a walk, gaining the courage to talk to other people, etc. We must be willing to make the change, for our own reasons, and listing the pros and cons of changing the behavior can help us out. Now we move to generating a description of the behavior which must be precise and unambiguous. Once we have clearly defined the behavior, we can then set goals to help us make the desired change. The definition and goals work hand-in-hand as we develop our treatment plan.

Module Outline

- 4.1. Behavioral Definitions

- 4.2. Goal Setting

- 4.3. Counting Behaviors

Module Learning Outcomes

- Clarify what a behavioral definition is and why it is important to applied behavior analysts.

- State the importance of setting clear goals in terms of what behavior you want to change.

- Count behaviors using the behavioral definition and your goals.

4.1. Behavioral Definitions

Section Learning Objectives

- Define and exemplify behavioral definition.

- Practice writing behavioral definitions for some of the behaviors on Planning Sheet 1.

- Write a behavioral definition for your own behavior to be changed.

- Explain how a behavior definition is like an operational definition.

If you are wanting to engage in behavioral change now, you likely already selected a behavior that you would like to either increase or decrease. It is critical to clearly define what the behavior is. In behavior modification, we call this a behavioral definition.

Our behavior may be an excess and something we need to decrease or a deficit and something we need to increase. No matter what type of behavior we need to change, we must state it with enough precision that anyone can read our behavioral definition and be able to accurately measure the behavior when it occurs. Let’s say you want to exercise more. You could define it as follows:

- 1 behavior = going to the gym and using a cardio machine (elliptical, treadmill, or stationary bike) for 20 minutes.

Okay, so if you went to the gym and worked out for 40 minutes, you would have made 2 behaviors. If you went to the gym for 60 minutes, you made 3 behaviors. What if you went to the gym for 30 minutes? Then you made 1.5 behaviors, correct? No. It does not make sense to count half a behavior.

Here are sample behavioral definitions for some of the pre-approved behaviors from Planning Sheet 1:

- Eating more fruits – 1 behavior = eating a single piece of fruit

- Pleasure reading – 1 behavior = reading 5 pages of a novel

- Using relaxation techniques – 1 behavior = meditating for 10 minutes

- Doing household chores – 1 behavior = cleaning one room in my apartment (kitchen, bathroom, living room, or bedroom)

- Quitting smoking – 1 behavior = smoking 1 cigarette

Keep your behavioral definition simple. Don’t make it reflect whatever your end goal will be, discussed in section 3.2. For instance, if your overall goal is to run for 60 minutes, do not make your behavioral definition to be 1 behavior = 60 minutes of running. Since we do not count partial behaviors, you will show no behaviors made until you finally reach 60 minutes of running. How low should you go then? If 60 is too high, do you define it as 1 behavior = 1 minute of running? Likely not. Think about what is the least amount of time you would run. If it is 5 minutes, you could set it at 1 behavior = 5 minutes of running. Then if you run 30 minutes you would have made 6 behaviors. If instead you set it at 1 behavior = 20 minutes of running, you can only count 1 behavior and the other 10 minutes are unaccounted for. Think about what denomination of time is most practical for your situation and where you are starting out at. If you have never run before, a smaller increment of time might be better. If you run 30 minutes a few days per week and want to simply double your time, then you could use a greater increment such as 10, 15, or 20 minutes.

It is prudent to create behavioral definitions for the target behavior but also any competing behaviors that may occur. If we want to go to the gym more often, we might discover when examining our antecedents that playing games on our phone in the morning or talking to our roommate in the afternoon leaves us with not enough time to work out. We would then define this competing behavior, or a behavior which interferes with the successful completion of a target behavior, and then when developing our plan, implement strategies that make the distractor less, well, distracting.

Before we move on to goals, it is important to point out that you likely know the concept of a behavioral definition on some level. In your introductory psychology course, or your research methods class, you should have talked about the operational definition which is a precise definition of all variables being studied. What if we were studying depression in our sample of college students? We might define it as how well the person holds down a job, class attendance, what the DSM 5 indicates, their own self-report about depressive thoughts, or physiological measures. The definition we use depends on the research question that is asked, and the group being studied. In any event, a behavioral definition is basically an operational definition applied to behavior modification procedures.

4.2. Goal Setting

Section Learning Objectives

- Define goal.

- List interesting features of goals.

- Describe properties of goals and how they relate to behavior modification.

- Differentiate proximal and distal goals.

- Exemplify how proximal and distal goals are used in behavior modification.

- Clarify how a criterion is used to move from one goal to the next.

4.2.1. What are Goals?

Once you have an idea of exactly what the behavior is you want to change, the next task is to set goals about the behavior. But what exactly is a goal?

For you as a student, the goal is to obtain your bachelor’s degree. You spend your time and energy studying, going to classes, writing papers, asking questions, and much more. After four years, you will be happy to take your diploma, which is what motivates you. You might even be driven to obtain the highest grades you can get to be competitive when you hit the job market or apply to graduate school.

4.2.2. Features of Goals

Goals have several interesting features. They can be large in scope. Obtaining the bachelor’s degree is a relatively large goal but if your terminal educational goal is to earn your Ph.D., then this is even larger in scope. Reading for pleasure is likely a small goal but losing 100 pounds is large and will take much more dedication. Goals can be complex and take planning to achieve. This is definitely the case with behavior modification. Even if you want to do something as simple as read for pleasure, you might have to implement quite a few additional changes in your life to make that happen. Obtaining a degree is complex and requires a great deal of planning and coordination with people like your major professor or adviser. Goals are more likely to be completed when they are linked to incentives. If your goal is to lose 100 pounds, reward yourself as you hit various milestones along the way. And finally, you can have more than one goal at a time. Maybe your goal is to exercise more and to restrict your calories. Or maybe you want to run both longer and faster (measures of frequency and intensity).

A few other properties of goals are worth mentioning here:

- The more difficult the goal, the more rewarding it is when we achieve it.

- Goals can be ranked in order of importance and higher-level goals have more value to us when achieved.

- The more specific the goal, the better our planning can be, and the more likely that we will achieve the goal.

- Goal commitment is key and if you want to make it more likely that you will achieve your goal, publicly announce the goal (Salancik, 1977). Commitment tends to be higher when the goal is more difficult too.

- If you fail at a goal, you can either try again, quit and move on, reduce the level of the goal, or revise the goal.

Another option to overcome goal failure might be to consider the use of subgoals, or waypoints toward the final goal. This leads to a discussion of distal vs. proximal goals. Distal goals are far off in the future whereas proximal are nearer in time. Go back to the example of changing our behavior such that we run for 60 minutes at a time 3 days a week (our distal goal). We will likely not start running 60 minutes, especially if we never ran a day in our life (except of course to the bathroom in times of crisis…enough said). We might create three additional goals of running for 15 minutes continuously 2 days a week, then running for 30 minutes continuously 3 days a week, and then running for 45 minutes continuously 3 days a week. Since we had not ran regularly in the past, we are changing duration and frequency in this scenario. Frequency goes from 2 to 3 days but note it may even be prudent to start at one day a week. Then our duration goes from 15 to 30 to 45 to 60 minutes. What is 4 goals in this scenario can expand to as many as we need to achieve our goal. Maybe another goal or two is needed (i.e. more proximal goals or steps along the way), and time will tell. As we achieve each proximal goal we should reward ourselves in some way (an incentive) and then of course we could use a bigger reward after the completion of the distal goal.

4.2.3. Criterion

But how do we know when to advance from one goal to the next? The specific “trigger” for when to advance from Goal 1 to Goal 2 is called the criterion and is linked to the changing-criterion design from Module 2.3. Our first goal states that we will run for 15 minutes 2 days a week. Achieved! When do we move to running 30 minutes for 3 days a week? That depends on the behavior we are trying to change. In exercise related projects or plans, it is prudent to make sure you can truly engage in that level of behavior for at least two weeks. Listen to your body, a trainer, or doctor, and then move to the next goal when it is safe to do so. For other projects such as pleasure reading, you could move to the next goal as soon as the current goal has been achieved. There is no need to wait as no serious harm can come from increasing the number of pages you read a night from 5 to 10, other than a few minutes of lost sleep.

This may lead you to wonder what length of time a goal should be maintained for. If I want to run three days a week, and do so Mon to Wed, can I move to my next goal starting Thursday? No. Frame your goals around one week at a time. So if you want to run three days a week, and finish your third day on Friday, then your second week of the current goal or first week of the next goal starts on Monday (if you define weeks as Monday through Sunday as we often do in academia). Otherwise, you could be pushing through goals too fast and not allowing yourself time to adjust. Though you are excited to bring about behavior change, if you do it too fast you might burn out and ultimately fail. On the other hand, moving too slow will create boredom. Find the right number of weeks to maintain each goal that is best for you. And this criterion might vary too. Earlier goals are likely easier to achieve than latter goals and so your criterion could be shorter for them (say 1 week) and longer for harder goals (say 2 weeks). Consider this when determining your criterion.

4.3. Counting Behaviors

Section Learning Objectives

- Explain how to count behaviors in your goals using the behavioral definition.

Keep in mind that the behavioral definition IS NOT a goal. It simply defines how you will count the target behavior, which is your dependent variable (DV).

4.3.1. Possibility 1: Duration

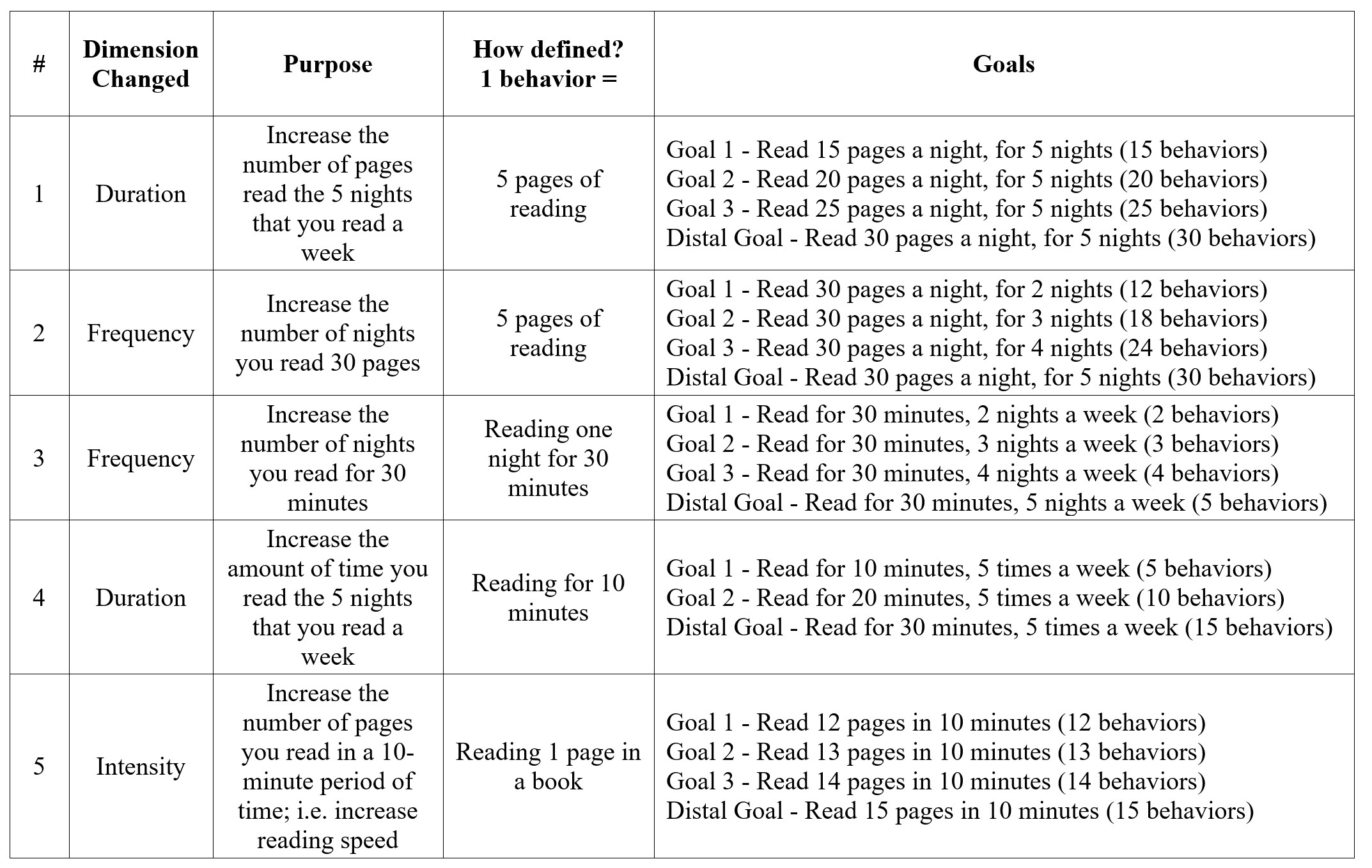

If your behavioral definition is 1 behavior = reading 5 pages in a book, and you read 15 pages, then you made 3 behaviors that day. If you read 20 the next day you made 4 behaviors, and then if you only read 10 pages the next you made 2 behaviors. If you read 12 pages, you still only made 2 behaviors. There are no partial behaviors (i.e. not 2.4 behaviors).

This links to your goals such that if you ultimately want to read 30 pages a night, 5 nights a week, then you will make 30 behaviors a week by the end of your plan. Where did 30 come from? One behavior = 5 pages of reading. If you read 30 pages a night, you are making 6 behaviors (30/5=6) per night. Since you want to read 30 pages a night for FIVE nights, you are making 30 total behaviors (6 behaviors a night x 5 nights = 30 total behaviors). Your subgoals or proximal goals could be as follows:

- Goal 1 – Read 15 pages a night, for 5 nights (15 behaviors)

- Goal 2 – Read 20 pages a night, for 5 nights (20 behaviors)

- Goal 3 – Read 25 pages a night, for 5 nights (25 behaviors)

- Distal Goal – Read 30 pages a night, for 5 nights (30 behaviors)

In this example, you are not changing the frequency (it is set at 5 nights) but are changing the duration (albeit indirectly). Reading 15 pages does not take as long as reading 20 pages, assuming your reading speed remains the same, and so it is sort of like assessing time.

4.3.2. Possibility 2: Frequency

But what if you can read 30 pages at a time now, and are having trouble reading 5 days a week? So duration is good but frequency is not. In this case, your goals look like:

- Goal 1 – Read 30 pages a night, for 2 nights (12 behaviors)

- Goal 2 – Read 30 pages a night, for 3 nights (18 behaviors)

- Goal 3 – Read 30 pages a night, for 4 nights (24 behaviors)

- Distal Goal – Read 30 pages a night, for 5 nights (30 behaviors)

Keep in mind the basic math that allowed us to arrive at those behavioral counts. For Goal 1, and all goals, you are making 6 behaviors a night. Why? 30/5 = 6. Remember that your behavioral definition was reading 5 pages. Then it is 6 behaviors a night x 2/3/4/5 nights to arrive at 12, 18, 24, and 30 behaviors, respectively.

4.3.3. Possibility 3: Frequency, again

Consider this now: 1 behavior = reading one night for 30 minutes. You might already be reading 30 minutes a night but want to increase the number of days, sort of like in my previous example. Duration is good but frequency is not. So:

- Goal 1 – Read for 30 minutes, 2 nights a week (2 behaviors)

- Goal 2 – Read for 30 minutes, 3 nights a week (3 behaviors)

- Goal 3 – Read for 30 minutes, 4 nights a week (4 behaviors)

- Distal Goal – Read for 30 minutes, 5 nights a week (5 behaviors)

The math – Reading one night for 30 minutes is one behavior and then times either 2/3/4/5 days which equals 2/3/4/5 behaviors, respectively.

4.3.4. Possibility 4: Duration, again

What if you are good about reading throughout the week but want to increase the time you spend reading? Now frequency is fine but duration is not. Your behavioral definition will be one behavior = reading for 10 minutes and your goals will be as follows:

- Goal 1 – Read for 10 minutes, 5 times a week (5 behaviors)

- Goal 2 – Read for 20 minutes, 5 times a week (10 behaviors)

- Distal Goal – Read for 30 minutes, 5 times a week (15 behaviors)

The math – Reading for 10 minutes was the behavioral definition and is one behavior. If you read for 20 minutes you are making 2 behaviors. If you read for 30 minutes you are making 3 behaviors. Multiple these numbers by 5 (number of days) to get the number of behaviors.

4.3.5. Possibility 5: Intensity

Now let’s get really crazy. What if duration and frequency are good, but you want to increase your reading speed, which is the behavioral dimension of intensity. How might you go about doing this? Well, the idea is that you can read more pages in a fixed amount of time. Since your progress will be slower than with the other examples, make your behavioral definition: 1 behavior = reading 1 page in a book. As for goals, well, this one is hard to do. Start with a set period of time such as reading for 10 minutes. You will need baseline data on what your reading rate is before implementing any treatment plan or making a conscientious effort to read faster. Say it is one page per minute. In 10 minutes, you will be making 10 behaviors. You want this to go up. If it does, it means you are reading faster. So:

- Goal 1 – Read 12 pages in 10 minutes (12 behaviors)

- Goal 2 – Read 13 pages in 10 minutes (13 behaviors)

- Goal 3 – Read 14 pages in 10 minutes (14 behaviors)

- Distal Goal – Read 15 pages in 10 minutes (15 behaviors)

At baseline you were reading 10 pages per minute and by completion of the distal goal you are reading 15 pages in 10 minutes which is a 50% faster rate. Of course, you could double your reading rate too which would mean making 20 behaviors instead of 10. Reading rate and intensity are tricky as you will want to also demonstrate the same level as comprehension as before. As long as that stays the same, you are effectively increasing your reading rate. The comprehension measure makes this type of project a bit more complicated but is an important piece. In this example, duration is set and intensity is changing. It would work much the same for increasing how fast you run. Frequency is not included in the example as it may not matter to you. You may just want to read faster when you do read. The duration of 10 minutes is there to standardize your data collection effort.

The above examples show that five students could have the same target behavior (reading for pleasure which is a deficit) but develop five different ways of approaching it based on what they want to get out of the project and what their current level of behavior is. Though the procedures are generally the same in behavior modification, how they are used in a specific plan can vary and do so dramatically.

To be sure you are clear on the different ways that behavioral definitions can appear, see the Table 4.1 below before proceeding:

4.3.6 Behavioral Excess and Counting Behaviors

How might this work with a behavioral excess? Consider the example of a person who loves pleasure shopping so much that he or she spends a significant amount of money each week. The person does not want to stop shopping; just reduce it. How might the individual handle this target behavior?

- Behavioral Definition – The target behavior is your dependent variable or the variable you will measure. So how will you measure pleasure shopping? One potential definition is 1 behavior = spending $10 at a store. What if you spend $58 in one location? You made 5 behaviors ($58/$10 = 5 behaviors; we don’t count partial behaviors).

- Current Level of Behavior – In our next module, we will discuss the functional assessment and the baseline phase. To set our goals effectively, we will need to know how much money we are spending each month while doing pleasure shopping (do not count grocery shopping). Let’s say we have this data now and know it is in excess of $600 which is over $150 per week. In terms of behavioral counts, we are making at least 60 behaviors a month or about 15 per week.

- Acceptable Level of Behavior (The Distal Goal) – We need to determine what level of behavior (shopping) we are okay with, or, how much money are we allowing ourselves to spend per week. Let’s say that is $70 per week, which means we reduce our spending from over $600 to a bit under $300, or at least a 50% reduction. Okay. This becomes our distal goal. How do we get there?

- Proximal Goals:

-

-

- Goal 1 – Spend no more than $150 a week (15 behaviors)

- Goal 2 – Spend no more than $120 a week (12 behaviors)

- Goal 3 – Spend no more than $100 a week (10 behaviors)

- Goal 4 – Spend no more than $90 a week (9 behaviors)

- Goal 5 (Distal) – Spend no more than $70 a week (7 behaviors)

-

- The Math – Remember that our behavioral definition says one behavior is spending $10 at a store. Take each of the amounts we are allowing ourselves to spend at each goal level and divide it by 10. When you do that you arrive at the number of behaviors, or 15, 12, 10, 9, and 7.

The point of an excess is to decrease the behavior either to 0 (not occurring at all and is extinct) or to a more acceptable level as with this example. You have to determine what is right for you. In the field of wellness, moderation is preached as key. If you want to reduce your caloric intake, you do not have to cut out all junk food. Just reduce it and track it as part of your new total daily allowance of calories. If a bag of chips is 120 calories, then add that into your total for the day (which may be 1200 calories). You do not have to get rid of chips; just don’t buy the big bag in which you are likely to keep reaching your hand into. Buy the small bags and just eat one at a time. You are still satisfying your craving and do not have to feel guilty for doing so. All things in moderation. This does not work with all excesses. If you are trying to quit smoking that does mean taking the behavior to 0 and since there are health risks with smoking, moderation is not useful here.

Module Recap

In Module 4, we continued with the process of planning for change. We discussed the need to precisely define our target and competing behaviors and gave examples of behaviors you might have chosen for your project. Once a precise definition is in place, we can formulate goals for how much we wish for the behavior to increase or decrease. We can also set short term or proximal goals to help us achieve the much larger or distal goal. Think about writing a 10-page paper. It is easier to say I am going to write the first section today, the next tomorrow, and then the final section the day after. Then I will revise and edit and print the paper to be submitted. These subgoals make the much larger task more manageable and easier to achieve. As this works with writing a paper, so too it can work with changing behavior.

Looking ahead to Module 5, you will learn how to go about discerning the ABCs of behavior. This will focus on what is called the functional assessment.

4th edition