Module Overview

Our final chapter in the textbook covers the last phase of behavior modification – maintenance. Once our behavior is occurring reliably, we need to begin to phase out most strategies we employed and ensure that we maintain our desired level of the target behavior. Also important is to make sure we do not fall back into old patterns, called relapse prevention.

Module Outline

Module Learning Outcomes

- State the importance of the maintenance phase and how to phase out strategies that are no longer needed.

- Develop a criterion for knowing when to move to maintenance.

- Describe issues that may occur during the maintenance phase.

- Propose strategies to make relapse less likely to occur.

- Clarify the role demands, stress, and coping play in relapse.

14.1. Maintenance Phase

Section Learning Objectives

- Describe the function of the maintenance phase.

- Identify specific strategies to phase out and propose ways to do this.

14.1.1. Maintenance Phase and Strategies to Phase or Fade

When planning to change our behavior we cannot lose sight of the fact that eventually, we will obtain our final goal. At this point, the target behavior is now occurring habitually or without conscious effort, or due to use of the many strategies we selected. Once this occurs, we need to transition from treatment phase to maintenance phase. Recall that the treatment phase is when we manipulate variables, or in this case use the various antecedent, behavior, and consequence focused strategies we have settled on. These cannot remain in effect for the duration of our life, so we must phase them out…well, most of them. Some strategies you will want to keep in place.

So which ones do we phase out and which do we keep? Table 14.1 gives you an idea of how to go about deciding this.

Table 14.1 Strategies to Keep and Strategies to Fade during Maintenance

| Strategies to Keep | Strategies to Phase Out or Fade |

| Goal Setting – goals are a regular part of life, though you will likely make many others not related to changing an unwanted behavior or making a new, desirable one | Antecedent Manipulations – you could make a case to keep a few, but in general you manipulated the antecedents to engage in your desired behavior. Once you are making it, these strategies are not needed. |

| Self-Instructions – reminding yourself what to do never hurts and people typically do this. | Generalization/Programming – you will want to make sure your behavior occurs in all relevant situations and environments, but once it does, it will not be needed. |

| Social support – friends and family regularly help us to do the right thing and outside of behavior modification, are critical buffers against stress. | Prompts – these do not regularly occur in life and so will be faded. Consider that when you start a new job, your trainer will use a lot of verbal, gestural, and modeling prompts. Once you know what you are doing, these prompts stop. |

| Relaxation techniques – we all encounter stress and anxiety on a regular basis and so muscle relaxation, deep breathing, etc. can be useful. | Shaping – once you are making the desired behavior, the shaping steps to get there are not needed. The same is true of training your cat to use the litter pan. Once he/she is doing so, reinforcing steps along the way are not needed. In fact, in shaping, once the next step is taken the previous ones cease to be reinforced and this includes making the final behavior. |

| Cognitive Behavior Modification – in general, these strategies may be useful in our everyday life. We all suffer depression, anxiety, fear, doubt ourselves, and eventually deal with loss, and so having additional skills to deal with these demands can help reduce stress. | Other Fear and Anxiety Procedures – once the fear is overcome, these procedures will not be needed but having been trained in how to use them will be useful should the fear return or a new one emerges. |

| Self-Praise – there is nothing wrong with patting yourself on the back when it is justified. Of course, we can fall into the self-serving bias if we are not careful. | Habit Reversal – once the habit has been reduced the competing response is no longer needed, unless the habit returns or a new one begins. |

| Record Keeping – See below. | Cognitive Behavior Modification – once the maladaptive cognition is under control, specific strategies such as cognitive restructuring, cognitive coping skills training, and acceptance techniques will not be needed. |

| Token economy – though a useful tool when trying to establish your target behavior, this type of system is not part of everyday life and so should be gradually phased out. To do this, change the schedule of when tokens are delivered, award less each time, and make your back up reinforcers cost much less. Eventually, the token economy will be forgotten. | |

| Differential reinforcement – recall that these strategies are meant to increase a desired behavior, eliminate a problem behavior, reduce the occurrence of a behavior, or to substitute a behavior. Once this has occurred, the procedure is not needed any more. This does not mean that reinforcement should be removed from life in general, just that it is not focused on a target behavior any more. | |

| Punishment Procedures – though punishment is a daily part of life such as getting a ticket for speeding, receiving a fine for making your credit card payment late, or being sent home from work for poor performance, any aversive control procedures established to help you make your target behavior and cease making a problem behavior will not be needed once you are reliably making the target behavior. | |

| Rules – since your plan is being faded out, you don’t need to use the rules that governed your behavior any more. They were in place to help you make the desired behavior and you are now doing so. |

Though not a strategy, it is important to continue recording keeping. Why is that? If you stop recording your behavior using your ABC chart and journal, you are more likely to stop making the behavior all together. Your records provide you with feedback as to how you are doing and remember: you can visually “see” your progress by obtaining counts, an average, a percentage, or by making a graph.

Once your target behavior has been established you should notice that the behavior increasingly falls under your control. But is it time to stop your plan? Consider that to move from one goal to the next we had a criterion to help us decide. You also have a criterion to decide when to move from the final goal and full implementation of your behavior modification plan to the maintenance phase. So what is it? You already engaged in this type of exercise once and back in Module 3. You were asked to answer the question: “On a scale from 1 (low) to 10 (high), how successful do you feel you will be with achieving your goal? Why? In other words, what is your self-efficacy?”

Now your question will be:

On a scale from 1 (low) to 10 (high), how successful do you feel you will be with maintaining your desired level of the target behavior without your behavior modification plan? Why? In other words, what is your self-efficacy?

Before moving on, consider this. If you do not state at least a 7, continue your plan until you can give this score at a minimum. Remember, maintenance phase implies that the behavior is under your control, and not being controlled by a token economy, differential reinforcement, punishment procedures, antecedent manipulations, etc…

14.1.2. Problems During Maintenance Phase

As with all things in life, we hit bumps in the road. We hit them when planning our behavior modification plan, likely hit a few as we employed the treatment, and even in maintenance phase we may hit some. In fact, there are two types of issues we may encounter during the maintenance phase:

- Maintenance Problem – Though we have gone to great lengths to ensure our target behavior stays at our desired level, based on the final goal, at times we falter. This is not necessarily due to a return to problem or undesirable behavior, but maybe just a loss of motivation for walking your dog every night, reading at bedtime, going to the gym, drinking water, studying more regularly, etc.

- Transfer Problem – Recall that we want to generalize our new behavior beyond just training situations/environments. If we establish good study habits when in our dorm, we want to do the same when studying in the student union or in the library. If we go to the gym regularly while at school, we want to do so at home on break. Or maybe you are studying well in all places, but this positive behavior only occurs for classes in your major. In all other classes, your poor study habits have not changed. So, you are performing as well as you want to in some instances, but not in all instances. The desirable behavior has not transferred or generalized as expected.

So how do we solve these issues? For maintenance issues, you could do the following:

- Look at your pros and cons for changing the behavior. Likely these have not changed but if they have, update them.

- Revisit your goals and reflect on how much you have accomplished, and likewise, how much you have to lose.

- Ask yourself how performing the desired/target behavior makes you feel. If you obtain happiness from making the new behavior, keep this in mind and maybe even develop a self-instruction as a reminder to engage in the desired behavior.

- Make sure you are still recording your behavior as noted above. This will give you feedback on your progress and information about potential temptations or mistakes you are making.

- Restate your commitment to your final goal, or maybe state your commitment to your new you, publically. Facebook and other social media tools work great for this.

- Seek social support. Ask friends and family to help you out.

- In dire situations, re-establish your behavior modification plan. Depending on how much time has passed since you last employed it, you might need to conduct another functional assessment and gather data about your current baseline if you have ceased data collection.

If you are having issues with transfer, you likely did not train yourself to transfer from the start. You will need to program for transfer now, which again, means generalizing beyond the training situation (See Module 7.5 for details). This is a conscious effort and the expression “practice makes perfect” comes into play. So, do just that. Practice using your new behavior in a variety of situations and environments. Enlist your social support network to help you and recall that prompts are used in programming. In extreme circumstances, you might need to obtain professional help.

14.2. Relapse Prevention

Section Learning Objectives

- Differentiate a lapse and a relapse.

- Suggest strategies to help make relapse less likely.

- Describe the model for coping with life’s demands and how it relates to relapse prevention.

14.2.1. Lapse vs. Relapse

Before understanding how to prevent relapse, we must distinguish the terms lapse and relapse. Simply, a lapse is when we make a mistake or slip up. Consider the expression, “Having a lapse in judgment.” This implies that we generally make sound decisions but in this one instance we did not. We made a mistake. What we don’t want is an isolated incident becoming a pattern of behavior. When this occurs, we have a relapse. Don’t beat yourself up if a lapse occurs. Our problem behavior will inevitably return at some point. We just don’t want it sticking around for the long term.

14.2.2. Temptations…Again

There are people and things that tempt us and situations or places that lead us to temptation more than others. To avoid a lapse turning into a relapse, reconsider high-risk situations and environments (these will be the ones you ranked higher on your scale) and the people who are present when we cave into temptation, that you identified when completing your functional assessment. Keeping good records of the ABCs of behavior, and your journal, will help you to identify these situations and people. Then you can develop new if-then plans to deal with them, or to re-establish old ones. Look at the rules you wrote for how to deal with these situations. It is likely you already have a plan in place and only need to implement it.

14.2.3. Emotion and Stress

Don’t let your emotions dictate your behavior. What does this mean? Consider the following model for who we respond to life’s challenges:

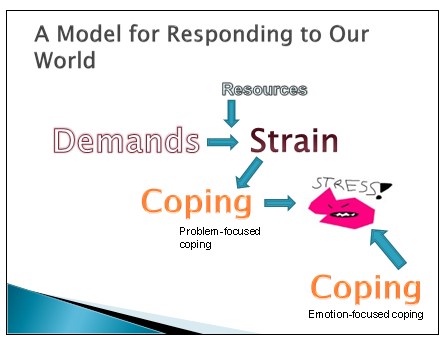

Figure 14.1. Model for Responding to Our World

14.2.3.1. Explaining the model. The model above is a useful way to understand the process of detecting, processing, interpreting and reacting to demands in our world. First, the individual detects a demand, or anything that has the potential to exceed a person’s resources and cause stress if a solution is not found. These demands could be something as simple as dealing with traffic while going to work, having an irritable boss, realizing you have four papers due in a week, processing the loss of a loved one or your job, or any other of a myriad of possible hassles or stressors we experience on a near daily basis. Once we have registered the demand and determined it to be emotionally relevant, we begin to think about what resources we have to handle it. Resources are anything we use to help us manage the demand and the exact resources we use will depend on what the demand is. For instance, the loss of a job might require you to look closer at how much money you have in savings and how long that money can realistically sustain you. Or if you have two exams and a paper due in one week, you might look at how busy your schedule is and find ways to free up time so you can get the work done. In both cases, you could use your social support network to help you out. Our resources may be inadequate to deal with the problem or can only help us for so long. When this occurs, we experience strain or the pressure the demand causes. This strain is uncomfortable and so we take steps to minimize it.

The best way to do this is to try to find a solution to the demand called problem focused coping (PFC). If you have a paper and a test in the same week you may go to your boss and ask to trade a shift with a coworker. This gives you the additional time you need to complete the paper and study for the test. If the boss refuses, you could always ask your professor for an extra day or two with the paper. If these strategies fail to manage or remove the demand we experience stress. You might think of stress as strain magnified enormously. Whereas strain may have left us a bit anxious, depressed, or exhausted, stress takes these symptoms to a whole new level. For some demands such as the loss of a loved one, the depression experienced in strain could reach clinical levels in stress. Now to effectively deal, you will need to consult a clinical psychologist. Or maybe when the big presentation in your public speaking class was a week away you only felt a bit anxious but now that it is… TODAY!!!! and in an hour… you are feeling very anxious. Not just that, you have a sick feeling in your stomach, your hands are shaking, you are breaking into a cold sweat, etc. Now your strain has manifested itself into something much more.

These physical, psychological, and behavioral reactions to stress have to be dealt with so you can either return to more rational strategies, if practical, or just “weather the storm” and wait for the demand to pass. Hence, you employ any one of a series of emotion focused coping (EFC) strategies. Think of stress as an emotional reaction. Hold out your arms and make a circle around your head. It’s a pretty big circle. Your initial reaction may be that big. If your EFC strategy works well your emotional reaction becomes smaller. Take those arms you likely still have in the air and start moving them in. As you do that, the circle becomes smaller. In the case of the presentation, you cannot take a 0 on it so you have to confront the demand head on and do the presentation. Better start imagining your audience in their underwear (See Module 8.2.2. and attention focused exercises for dealing with anxiety)!

14.2.3.2. Demands, resources, and strain. You might think of demands as being assigned to one of two major categories – daily hassles or stressors. Within these two major categories are various subtypes which we will explore now.

The first major class of demands is daily hassles. What are they? Daily hassles are petty annoyances that over time take a toll on us. There are three types of daily hassles. Pressure is when we feel forced to speed up, intensify, or shift direction in our behavior. What pressures do you experience in school? At your job? In your fraternity or sorority? From your coach? Frustration occurs when a person is prevented from reaching a goal because something or someone stands in the way. Examples of frustrations include money and delays. Some of you can relate to the first two if you have ever had to wait for your financial aid to post to your student account and did not have the money to buy textbooks before the first day of class. Then your professors are assigning readings in the first week but how do you complete them without a book? This is may be where having a friend helps out – assuming this friend is not waiting like you are! Finally, conflict arises when we face two or more incompatible demands, opportunities, needs, or goals. We all have experienced this one. Whether the conflict is with a roommate, significant other, boss, professor, parents, etc., these little conflicts alone are no big deal but if they keep occurring can cause problems. Did you ever have to break up with your boyfriend or girlfriend because these conflicts became the highlight of your relationship and never seemed to resolve themselves? Did you ever drop a class or quit a job for the same reason? If so, you understand the cumulative effects of conflict.

Think about the types of daily hassles discussed above. Isolated, they are not a big deal. But have you ever noticed that what was not a big deal at the beginning of the week really starts to get under your skin by the end of the week? For instance on Monday, having to run class-to-class, drive to work and sit in traffic, wait in line for lunch, etc. are mere inconveniences that can be dealt with. By Friday they have become infuriating and annoying. In other words, over time daily hassles take a toll on us and we likely experience several at the same time (i.e. pressure to do well, not having enough money, and conflict with a roommate, for instance).

The second major class of demands is stressors, a term you may have heard before. What are they? Stressors are environmental demands that create a state of tension or threat and require change or adaptation. Most people assume that it is only bad things that cause stress. But is this true? Can good things cause stress also? The answer is ‘yes’ and these good things are a special type of stressor called eustressors (Selye, 1976). When we think of things usually equated with stress, these are technically called distressors. Coming up with a list of distressors is easy. What are some good things that can create stress too?

There are three types of stressors, whether eustress or distress:

- Change is anything, whether good or bad, that requires us to adapt. What change have you had to deal with recently? For many of you, starting college is likely a stressor you’ve been dealing with. Think about it for a minute. A few months ago you were living at home and under your parent’s rules. Now you are on your own, and within reason, living under your own rules. For many students the change college life represents is difficult and it takes a year or two to fully make the transition. The danger is that during this time, grades may suffer. One important thing to consider with change is that the more you need, the greater the stress.

- Extreme Stressors are stressors that have the ability to move a person from demand to stress very fast. Examples include divorce, catastrophes, and combat. Hopefully you haven’t had to deal with any extreme stressors recently but if you have, they would most likely take the form of the loss of a loved one or some type of catastrophe such as a natural disaster. Why? Because we live in a country that is fortunately not experiencing war firsthand, many of you are not married and so divorce or separation is not an issue, and even if you are working it is likely just for extra money and so unemployment is no real threat. In your life you will encounter at least one devastating situation and the distinguishing feature of extreme stressors is their ability to move you from demand to stress very quickly. In other words, many of them create stress immediately unless you had time to prepare. Maybe you knew your company was going to be doing layoffs and so you spent the months leading up to your dismissal putting money on the side, preparing your resume, and applying for jobs. Or maybe you knew a loved one was dying and it was just a matter of time. So you said your good-byes and made peace with their absence. It’s when these events occur without prior warning that they are most detrimental to us.

- Self-Imposed Stressors – Okay so let’s face it. For some of the students in the class, possibly including you, psychology is not your cup of tea. You are fine with just getting by and passing the class and there is nothing wrong with that. But when you take classes in your major that ‘getting by’ strategy will not cut it and you know it. So you have put pressure on yourself to excel in the classes related to your major. In fact, one strategy you likely came up with is to focus more time on these courses and less on those that do not matter as much. This could be a great strategy but be cautious that you do not let these other classes go too much and therefore cause yourself the distress of failing them, being put on academic probation, and/or having to take them again!

The next step in the process is to start figuring out something to do about the demand. The obvious task is to see what resources you have and as previously noted, these are specific to the demand. Think about what resources you would have at your disposal to handle the following:

- Daily Hassle –> Frustration –> Traffic

- Daily Hassle –> Conflict –> Constant arguing with your girl/boyfriend

- Eustressor – Birth of a new baby

- Extreme Stressor – Loss of your job

- Self-imposed Stressor – Student athlete with a swim meet in one week

- Distressors – Three exams and one paper in a week

So you likely made a great list of resources for each of the demands listed above. These resources may be adequate to deal with the demand and so you have no problem. In the case of demands that arise from being a student, you are likely able to handle everything thrown at you early in the semester but as demands build on one another, your resources are exhausted and you experience strain. Strain is the pressure the demand causes; occurs when our resources are insufficient to handle the demand. It may be experienced as exhaustion, anxiety, depression, discomfort, uneasiness, tension, or fatigue.

14.2.3.3. Stress. Stress is one of those terms that everyone uses but no one can really define. Much of what we know about stress can be attributed to the work of Hungarian endocrinologist, Hans Selye (1907-1982). Selye (1973) defined stress as “the nonspecific response of the body to any demand made upon it” (pg. 692) and pointed out that the important part of the definition was the word nonspecific. Though each demand exerts a unique influence on our body, such as sweating due to heat and so in a sense is specific, all demands require adaptation regardless of what the problem is, making them nonspecific. Selye writes, “That is to say, in addition to their specific actions, all agents to which we are exposed produce a nonspecific increase in the need to perform certain adaptive functions and then to reestablish normalcy, which is independent of the specific activity that caused the rise in requirements” (pg. 693).

It is important to also state what stress is not since the term has been used loosely. Selye says stress is not…

- simply nervous tension – Stress reactions occur in lower organisms with no nervous system and in plants.

- the result of damage – “Normal activities – a game of tennis or even a passionate kiss – can produce considerable stress without causing conspicuous damage” (pg. 693).

- something to be avoided – In fact, Selye says stress cannot be avoided as there will always be demands in our environment, even when sleeping as in the form of digesting that night’s dinner. Furthermore, adaptation and growth can occur from it.

So how do we get to the point of stress? Selye (1973) talked about what he called the General Adaptation Syndrome or a series of three stages the body goes through when a demand is encountered in the world. We already discussed this in Module 8.2.1. and so will not cover it again.

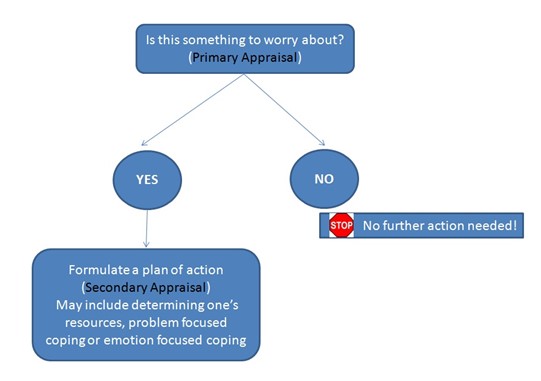

14.2.3.4. Coping. Alright so let’s talk about coping with demands and coping with stress but as a prelude to this, it is necessary to discuss appraisal or the process of interpreting the importance of a demand and how we might react to it (Folkman and Lazarus, 1985; Lazaraus and Folkman, 1984). When a demand is detected we have to decide if this is something we need to worry about. In other words, we need to ask ourselves is it relevant, benign, positive, or stressful? This process is called primary appraisal (PA) and is governed by the amygdala (Phelps & LeDoux, 2005; Ohman, 2002; LeDoux, 2000) which is used to determine the emotional importance of events so that we can either approach or withdraw. You might think of primary appraisal as answering the question with a one word answer. If the question regards what the nature of the event is, we could answer with one of the words above. If the question is whether or not this is something to worry about, then we might answer with a ‘Yes’ or ‘No.’ Either way, the answer is simple and a word or two are only required.

Let’s say we decide it is something to worry about. So what do we do? That is where secondary appraisal (SA) comes in. You might think of it as developing strategies to meet the demands that life presents us or forming a plan of action. This is controlled by the prefrontal cortex of the cerebrum (Ochsner et al., 2002; Miyake et al., 2000). These strategies range from assessing our resources, using problem focused coping and then later using emotion focused coping.

The level at which the brain processes information gets more sophisticated as you move from one major area of the brain to the next. The initial detecting of environmental demands occurs due to the actions of the various sensory systems and then this information travels to the thalamus of the central core. From there, we need to determine if it is something to worry about and so it travels to the limbic system and the amygdala. Recall too that in the limbic system it is the hippocampus which governs memory. We also try and access memories of similar demands (or the same one) experienced in the past to know if we need to worry. Finally, we take the simple answer obtained in the amygdala and if it is something to truly worry about, a plan of action needs to be decided upon which involves the most sophisticated area of the brain or the cerebrum and the prefrontal cortex specifically. So how we handle this information and what we do with it becomes increasingly detailed as we move up from the lowest area of the brain to the highest.

Figure 14.2. Appraisal Decision Matrix

So once we determine there is a demand we need to respond to, we do just that, respond. If our resources have been surpassed we experience strain and begin to use problem focused coping. Notice the name for a minute. Problem focused coping does just that. It is a type of coping focused on the problem itself. This problem is the demand we are facing. This should help you distinguish it from emotion focusing coping which will be defined in a bit. There are three types of PFC:

- Confrontation – when we attack a problem head on.

- Compromise – when we attempt to find a solution that works for all parties

- Withdrawal – when we avoid a situation when other forms of coping are not practical

A logical question to ask is whether one strategy produces more favorable outcomes over the others. The answer is that no single strategy is really better, but their effectiveness depends on the demand. For some demands, all PFC strategies may help whereas for others only one may be practical. Again, it depends on the demand.

So within the model we have been working off of in Figure 14.1, when PFC does not work we experience stress. Recall earlier that stress was described as the giant circle around our heads (that is, if we held our hands up and formed a circle). The second type of coping, emotion focused coping (EFC), deals with the emotional response. This response could be intense happiness as with eustressors, or frustration, anger, sadness, etc. To be able to deal with the demand and its stress from a rational perspective, we need to manage the emotional reaction we are having. This is where emotion focused coping comes in. You can distinguish it from PFC if you recall that stress is our emotional reaction and we need to manage it.

There are six types of EFC:

- Wishful thinking – when a person hopes that a bad situation goes away or a solution magically presents itself

- Distancing – when the person chooses not to deal with a situation for some time

- Emphasizing the positive – when we focus on good things related to a problem and downplay negative ones

- Self-blame – when we blame ourselves for the demand and subsequent stress we are experiencing

- Tension reduction – when a person engages in behaviors to reduce the stress caused by a demand; may include using drugs or alcohol, eating comfort foods, or watching a funny movie

- Self-isolation – when a person intentionally removes themselves from social situations to avoid having to face a demand.

NOTE: At times, we may not be able to use any rational strategy to deal with a demand (PFC) and can only wait until it passes or ends. To be able to do this successfully, we need to manage the emotional reaction (EFC). Also, notice that some of the EFC strategies sound like the maladaptive cognitions discussed in Module 8.4.1.

14.2.3.5. What this means for relapse prevention. We often engage in problem behaviors or make bad decisions when we are angry, upset, depressed, anxious, or bored. We fall into these states due to demands in our environment. The EFC strategies mentioned above can help you to manage the stress so you can return to PFC strategies and deal with the demand itself. But be careful, some of the forms tension reduction takes are health defeating behaviors and temptations in plans such as working out more, drinking water, losing weight, eliminating or reducing alcohol consumption, quitting smoking, etc. Stress has the ability to undermine the best laid plan.

The best advice I have is that if you are in an emotional state or stressed out, avoid high-risk situations, environments, and people all together. The best way to not have a problem is to make it a non-factor from the start. In general, you cannot acquire a STD if you don’t have sex! You won’t feel guilty about having a beer if you don’t go to the bar from the start. J

Module Recap

In Module 14, we discussed the final stage of our behavior modification plan – maintenance. Knowing when to move to this stage is half the battle and the other half is knowing what to do when we have maintenance or transfer issues. Our bad behavior will rear its ugly head, and this is to be expected, but what we need to do is prevent it from becoming the norm and not the exception. This is where relapse prevention comes in. Effective stress management can go a long way to helping us to avoid tempting people, things, situations, and environments, and to allow rational processes to govern our behavior.

4th edition