3rd edition as of July 2023

Module Overview

In Module 13, we will cover matters related to personality disorders to include their clinical presentation, epidemiology, comorbidity, etiology, and treatment options. Our discussion will include Cluster A disorders of paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal; Cluster B disorders of antisocial, borderline, histrionic, and narcissistic; and Cluster C personality disorders of avoidant, dependent, and obsessive-compulsive. Be sure you refer Modules 1-3 for explanations of key terms (Module 1), an overview of the various models to explain psychopathology (Module 2), and descriptions of the therapies (Module 3).

Module Outline

Module Learning Outcomes

- Describe how personality disorders present.

- Describe the epidemiology of personality disorders.

- Describe comorbidity in relation to personality disorders.

- Describe the etiology of personality disorders.

- Describe treatment options for personality disorders.

13.1. Clinical Presentation

Section Learning Objectives

- Define personality trait.

- Define personality disorder.

- List the defining features of personality disorders.

- Describe the three clusters.

- Describe how paranoid personality disorder presents.

- Describe how schizoid personality disorder presents.

- Describe how schizotypal personality disorder presents.

- Describe how antisocial personality disorder presents.

- Describe how borderline personality disorder presents.

- Describe how histrionic personality disorder presents.

- Describe how narcissistic personality disorder presents.

- Describe how avoidant personality disorder presents.

- Describe how dependent personality disorder presents.

- Describe how obsessive-compulsive personality disorder presents.

13.1.1. Overview of Personality Disorders

According to the DSM-5-TR, personality traits are “…enduring patterns of perceiving, relating to, and thinking about the environment and oneself that are exhibited in a wide range of social and personality contexts while a personality disorder “…is an enduring pattern of inner experience and behavior that deviates markedly from the norms and expectations of the individual’s culture, is pervasive and inflexible, and has an onset in adolescence or early adulthood, is stable over time, and leads to distress or impairment” (APA, 2022, pg. 733). Personality disorders have four defining features, which include distorted thinking patterns, problematic emotional responses, over- or under-regulated impulse control, and interpersonal difficulties. While these four core features are universal among all ten personality disorders, the DSM-5-TR divides the personality disorders into three different clusters based on symptom similarities.

Cluster A is described as the odd or eccentric cluster and consists of paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal personality disorders. The common feature between these three disorders is social awkwardness and social withdrawal. Often these behaviors are similar to those seen in schizophrenia; however, they tend to be not as extensive or impactful on daily functioning as seen in schizophrenia. In fact, there is a strong relationship between Cluster A personality disorders among individuals who have a relative diagnosed with schizophrenia (Chemerinksi & Siever, 2011).

Cluster B is the dramatic, emotional, or erratic cluster and consists of antisocial, borderline, histrionic, and narcissistic personality disorders. Individuals with these personality disorders often experience problems with impulse control and emotional regulation. Due to the dramatic, emotional, and erratic nature of these disorders, it is nearly impossible for individuals to establish healthy relationships with others.

And finally, Cluster C is the anxious or fearful cluster and consists of avoidant, dependent, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders. As you read through the descriptions of the disorders, you will see an overlap with symptoms from the anxiety and depressive disorders. Cluster C disorders have the most treatment options of all the personality disorders, likely because the overlapping anxiety and depressive disorders have well-established treatment options.

To meet the criteria for any personality disorder, the individual must display the pattern of behaviors in adulthood. Children cannot be diagnosed with a personality disorder. Some children may present with similar symptoms, such as poor peer relationships, odd or eccentric behaviors, or peculiar thoughts and language; however, a formal personality disorder diagnosis cannot be made until the age of 18. The DSM-5-TR reports that median prevalence across several countries is 3.6% for Cluster A disorders, 4.5% for Cluster B, 2.8% for Cluster C, and 10.5% for any personality disorder.

It is also noted that the clustering approach used in the DSM has not been consistently validated and has some serious limitations. As written, “An alternative to the categorical approach is the dimensional perspective that personality disorders represent maladaptive variants of personality traits that merge imperceptibly into normality and into one another” (APA, 2022, pg. 734). Interested readers should consult Section III of the DSM (beginning on page 881) for a full description of the dimensional model for personality disorders and an alternative model for personality disorders that utilizes a hybrid dimensional-categorical model approach.

13.1.2. Cluster A

13.1.2.1. Paranoid personality disorder. Paranoid personality disorder is characterized by a marked distrust or suspicion of others. Individuals interpret and believe that other’s motives and interactions are intended to harm them, and therefore, they are skeptical about establishing close relationships outside of family members—although, at times, even family members’ actions are also believed to be malevolent (APA, 2022). Individuals with paranoid personality disorder often feel as though they have been deeply and irreversibly hurt by others even though they lack evidence to support that these others intended to or did hurt them. Because of these persistent suspicions, they will doubt relationships that show true loyalty or trustworthiness. Compliments are misinterpreted and they may view an offer of help as a criticism that they are not doing a good enough job on their own.

Individuals with paranoid personality disorder are also hesitant to share any personal information or confide in others as they fear the information will be used against them. Additionally, benign remarks or events are often viewed as demeaning or threatening. For example, if an individual with paranoid personality disorder was accidentally bumped into at the store, they would interpret this action as intentional, with the purpose of causing them injury. Because of this, individuals with paranoid personality disorder are quick to hold grudges and unwilling to forgive insults or injuries- whether intentional or not. They are known to quickly and angrily counterattack, either verbally or physically, in situations where they feel they were insulted (APA, 2022).

13.1.2.2. Schizoid personality disorder. Individuals with schizoid personality disorder display a persistent pattern of avoidance of social relationships, along with a limited range of emotional expression in interpersonal settings (APA, 2022). Similar to those with paranoid personality disorder, individuals with schizoid personality disorder do not have many close relationships; however, unlike paranoid personality disorder, this lack of connection is not due to suspicious feelings, but rather, the lack of desire to engage with others and the preference to engage in solitary behaviors. Individuals with schizoid personality disorder are often viewed as “loners” and prefer activities where they do not have to engage with others (APA, 2022). Established relationships rarely extend outside that of the family as they make no effort to start or maintain friendships. This lack of establishing social relationships also extends to sexual behaviors, as these individuals report a lack of interest in engaging in sexual experiences with others.

Regarding the limited range of emotion, individuals with schizoid personality disorder are often indifferent to criticisms or praises of others and appear not to be affected by what others think of them. Individuals will rarely show any feelings or expressions of emotion and are often described as having a “bland” exterior (APA, 2022). In fact, individuals with schizoid personality disorder rarely reciprocate facial expressions or gestures typically displayed in normal conversations such as smiles or nods. Because of this lack of emotion, there is a limited need for attention or acceptance.

13.1.2.3. Schizotypal personality disorder. Schizotypal personality disorder is characterized by a range of impairment in social and interpersonal relationships due to discomfort in relationships, along with odd cognitive or perceptual distortions and eccentric behaviors (APA, 2022). Similar to those with schizoid personality disorder, individuals also seek isolation and have few, if any established relationships outside of family members.

One of the most prominent features of schizotypal personality disorder is ideas of reference, or the belief that unrelated events pertain to them in a particular and unusual way. Ideas of reference also lead to superstitious behaviors or preoccupation with paranormal activities that are not generally accepted in their culture (APA, 2022). The perception of special or magical powers, such as the ability to mind-read or control other’s thoughts, has also been documented in individuals with schizotypal personality disorder. Similar to schizophrenia, unusual perceptual experiences such as auditory hallucinations, as well as unusual speech patterns of derailment or incoherence, are also present.

Like the other personality disorders within cluster A, there is a component of paranoia or suspiciousness of other’s motives. Additionally, individuals with schizotypal personality disorder display inappropriate or restricted affect, thus impacting their ability to appropriately interact with others in a social context. Significant social anxiety is often also present in social situations, particularly in those involving unfamiliar people. The combination of limited affect and social anxiety contributes to their inability to establish and maintain personal relationships; most individuals with schizotypal personality disorder prefer to keep to themselves to reduce this anxiety.

13.1.3. Cluster B

13.1.3.1. Antisocial personality disorder. The essential feature of antisocial personality disorder is the persistent pattern of disregard for, and violation of, the rights of others. This pattern of behavior begins in late childhood or early adolescence and continues throughout adulthood. While this behavior presents before age 15, the individual cannot be diagnosed with antisocial personality disorder until the age of 18. Prior to age 18, the individual would be diagnosed with conduct disorder. Although not discussed in this book as it is a disorder of childhood, conduct disorder involves a repetitive and persistent pattern of behaviors that violate the rights of others or major age-appropriate norms. Common behaviors of individuals with conduct disorder that go on to develop antisocial personality disorder are aggression toward people or animals, destruction of property, deceitfulness or theft, or serious violation of rules (APA, 2022).

While commonly referred to as “psychopaths” or “sociopaths,” individuals with antisocial personality disorder fail to conform to social norms. This also includes legal rules as individuals with antisocial personality disorder are often repeatedly arrested for property destruction, harassing/assaulting others, or stealing (APA, 2022). Deceitfulness is another hallmark symptom of antisocial personality disorder as individuals often lie repeatedly, generally to gain profit or pleasure. There is also a pattern of impulsivity—decisions made in the moment without forethought of personal consequences or consideration for others (Lang et al., 2015). This impulsivity also contributes to their inability to hold jobs as they are more likely to impulsively quit their jobs (Hengartner et al., 2014). Employment instability, along with impulsivity, also impacts their ability to manage finances; it is not uncommon to see individuals with antisocial personality disorder with large debts that they are unable to pay (Derefinko & Widiger, 2016).

While also likely related to impulsivity, individuals with antisocial personality disorder tend to be extremely irritable and aggressive, repeatedly getting into fights. The marked disregard for their safety, as well as the safety of others, is also observed in reckless behavior such as speeding, driving under the influence, and engaging in sexual and substance abuse behavior that may put themselves at risk (APA, 2022).

Of course, the most known and devastating symptom of antisocial personality disorder is the lack of remorse for the consequences of their actions, regardless of how severe they may be. Individuals often rationalize their actions as the fault of the victim, minimize the harmfulness of the consequences of their behaviors, or display indifference (APA, 2022). Overall, individuals with antisocial personality disorder have limited personal relationships due to their selfish desire and lack of moral conscience.

13.1.3.2. Borderline personality disorder. Individuals with borderline personality disorder display a pervasive pattern of instability in interpersonal relationships, self-image, and affect (APA, 2022). The combination of these symptoms causes significant impairment in establishing and maintaining personal relationships. They will often go to great lengths to avoid real or imagined abandonment. Fears related to abandonment can lead to inappropriate anger as they often interpret the abandonment as a reflection of their own behavior. It is not uncommon to experience intense fluctuations in mood, often observed as volatile interactions with family and friends (Herpertz & Bertsch, 2014). Those with borderline personality disorder may be friendly one day and hostile the next.

To prevent abandonment, individuals with borderline personality disorder will often exhibit impulsive behaviors such as self-harm and suicidal behavior. In fact, individuals with borderline personality disorder engage in more suicide attempts, and completion of suicide is higher among these individuals than the general public (Linehan et al., 2015). Other impulsive behaviors, such as non-suicidal self-injury (cutting) and sexual promiscuity, are frequently seen within this population, typically occurring during high-stress periods (Sansone & Sansone, 2012). They often have chronic feelings of emptiness along with painful feelings of aloneness. Occasionally, hallucinations and delusions are present, particularly of a paranoid nature; however, these symptoms are often transient and recognized as unacceptable by the individual (Sieswerda & Arntz, 2007).

13.1.3.3. Histrionic personality disorder. Histrionic personality disorder is the first personality disorder that addresses pervasive and excessive emotionality and attention-seeking. These individuals are usually uncomfortable in social settings unless they are the center of attention. To help gain attention, the individual is often vivacious and dramatic, using physical gestures and mannerisms along with grandiose language. These behaviors are initially very charming to their audience; however, they begin to wear due to the constant need for attention to be on them. If the theatrical nature does not gain the attention they desire, they may go to great lengths to draw attention, such as using a fictitious story or creating a dramatic scene.

To ensure they gain the attention they desire, individuals with histrionic personality disorder frequently dress and engage in sexually seductive or provocative ways. These sexually charged behaviors are not only directed at those in which they have a sexual or romantic interest but to the general public as well (APA, 2022). They often spend a significant amount of time on their physical appearance to gain the attention they desire.

Individuals with histrionic personality disorder are easily suggestible. Their opinions and feelings are influenced by not only their friends but also by current fads (APA, 2022). They also tend to exaggerate relationships, considering casual acquaintanceships as more intimate than they are.

13.1.3.4. Narcissistic personality disorder. Like histrionic personality disorder, narcissistic personality disorder also centers around the individual; however, with narcissistic personality disorder, individuals display a pattern of grandiosity along with a lack of empathy for others (APA, 2022). The grandiose sense of self leads to an overvaluation of their abilities and accomplishments. They often come across as boastful and pretentious, repeatedly proclaiming their superior achievements. These proclamations may also be fantasized to enhance their success or power. Oftentimes they identify themselves as “special” and will only interact with others of high status.

Given the grandiose sense of self, it is not surprising that individuals with narcissistic personality disorder need excessive admiration from others. While it appears that their self-esteem is hugely inflated, it is very fragile and dependent on how others perceive them (APA, 2022). Because of this, they may constantly seek out compliments and expect favorable treatment from others. When this sense of entitlement is not upheld, they can become irritated or angry that their needs are not met.

A lack of empathy is also displayed in individuals with narcissistic personality disorder as they often struggle to (or choose not to) recognize the desires or needs of others. This lack of empathy also leads to exploitation of interpersonal relationships, as they are unable to understand other’s feelings (Marcoux et al., 2014). They often become envious of others who achieve greater success or possessions than them. Conversely, they believe everyone should be envious of their achievements, regardless of how small they may be.

13.1.4. Cluster C

13.1.4.1. Avoidant personality disorder. Individuals with avoidant personality disorder display a pervasive pattern of social inhibition due to feelings of inadequacy and increased sensitivity to negative evaluations (APA, 2022). The fear of being rejected drives their reluctance to engage in social situations so that they may prevent others from evaluating them negatively. This fear extends so far that it prevents individuals from maintaining employment due to their intense fear of negative evaluation or rejection.

Socially, they have very few if any friends, despite their desire to establish social relationships. They actively avoid social situations in which they can develop new friendships out of the fear of being disliked or ridiculed. Similarly, they are cautious of new activities or relationships as they often exaggerate the potential negative consequences and embarrassment that may occur; this is likely a result of their ongoing preoccupation with being criticized or rejected by others. Within intimate relationships, their fear of being shamed or ridiculed leads to restraint, and they view themselves as socially inept (APA, 2022).

Making Sense of the Disorders

As you read the clinical description of avoidant personality disorder, did you think it sounded a lot like social anxiety disorder? You likely did as there is a great deal of overlap between the two disorders. So, how do they differ if they are to be regarded as separate diagnostic categories in the DSM? This difference is linked to self-concept. How so?

- In social anxiety disorder the negative self-concept is unstable and less pervasive and entrenched.

- In avoidant personality disorder, the negative self-concept is more stable as an enduring and pervasive pattern, typical of personality traits.

Additionally, avoidant personality disorder frequently occurs in the absence of social anxiety disorder and some separate risk factors have been identified for the two.

13.1.4.2. Dependent personality disorder. Dependent personality disorder is characterized by pervasive and excessive need to be taken care of by others (APA, 2022). This intense need leads to submissive and clinging behaviors as they fear they will be abandoned or separated from their parent, spouse, or another person with whom they are in a dependent relationship. They are so dependent on this other individual that they cannot make even the smallest decisions without first consulting with them and gaining their approval or reassurance. They often allow others to assume complete responsibility for their life, making decisions in nearly all aspects of their lives. Rarely will they challenge these decisions as their fear of losing this relationship greatly outweighs their desire to express their own opinion. Should the relationship end, the individual experiences significant feelings of helplessness and quickly seeks out another relationship to replace the old one (APA, 2022).

When they are on their own, individuals with dependent personality disorder express difficulty initiating and engaging in tasks on their own. They lack self-confidence and feel helpless when they are left to care for themselves or engage in tasks on their own. So that they do not have to engage in tasks alone, individuals will go to great lengths to seek out support of others, often volunteering for unpleasant tasks if it means they will get the reassurance they need (APA, 2022).

13.1.4.3. Obsessive-compulsive personality disorder (OCPD). OCPD is defined by an individual’s preoccupation with orderliness, perfectionism, and ability to control situations that they lose flexibility, openness, and efficiency in everyday life (APA, 2022). One’s preoccupation with details, rules, lists, order, organization, or schedules overshadows the larger picture of the task or activity. In fact, the need to complete the task or activity is significantly impacted by the individual’s self-imposed high standards and need to complete the task perfectly, that the task often does not get completed. The desire to complete the task perfectly often causes the individual to spend an excessive amount of time on the task, occasionally repeating it until it is to their standard. Due to repetition and attention to fine detail, the individual often does not have time to engage in leisure activities or engage in social relationships. Despite the excessive amount of time spent on activities or tasks, individuals with OCPD will not seek help from others, as they are convinced that the others are incompetent and will not complete the task up to their standard.

Personally, individuals with OCD are rigid and stubborn, particularly with their morals, ethics, and values. Not only do they hold these standards for themselves, but they also expect others to have similarly high standards, thus causing significant disruption to their social interactions. The rigid and stubborn behaviors are also seen in their financial status, as they are known to live significantly below their means to prepare financially for a potential catastrophe (APA, 2022). Similarly, they may have difficulty discarding worn-out or worthless items, despite their lack of sentimental value.

Though on the surface it may appear that OCPD and OCD are one and the same, there is a distinct difference as the personality disorder lacks definitive obsessions and compulsions (APA, 2022). In fact, most individuals with OCD do not have a pattern of behavior that meets criteria for this personality disorder.

Key Takeaways

You should have learned the following in this section:

- Personality disorders share the features of distorted thinking patterns, problematic emotional responses, over- or under-regulated impulse control, and interpersonal difficulties and divide into three clusters.

- Cluster A personality disorders are described as the odd/eccentric cluster and share as the common feature social awkwardness and social withdrawal. It consists of paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal personality disorders.

- Cluster B personality disorders are described as the dramatic, emotional, or erratic cluster and consists of antisocial, borderline, histrionic, and narcissistic personality disorders.

- Cluster C is the anxious/fearful cluster and consists of avoidant, dependent, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders.

- Paranoid personality disorder is characterized by a marked distrust or suspicion of others.

- Schizoid personality disorder is characterized by a persistent pattern of avoidance of social relationships, along with a limited range of emotion among social relationships.

- Schizotypal personality disorder is characterized by a range of impairment in social and interpersonal relationships due to discomfort in relationships, along with odd cognitive or perceptual distortions and eccentric behaviors.

- Antisocial personality disorder is characterized by a persistent pattern of disregard for, and violation of, the rights of others. They show no remorse for their behavior

- Borderline personality disorder is characterized by a pervasive pattern of instability in interpersonal relationships, self-image, and affect.

- Histrionic personality disorder is characterized by pervasive and excessive emotionality and attention-seeking.

- Narcissistic personality disorder is characterized by a pattern of grandiosity along with a lack of empathy for others.

- Avoidant personality disorder is characterized by a pervasive pattern of social anxiety due to feelings of inadequacy and increased sensitivity to negative evaluations.

- Dependent personality disorder is characterized by pervasive and excessive need to be taken care of by others.

- OCPD is characterized by an individual’s preoccupation with orderliness, perfectionism, and the ability to control situations that they lose flexibility, openness, and efficiency in everyday life.

Section 13.1 Review Questions

- What are personality traits and how do they lead to personality disorders?

- What are the three clusters? How are disorders grouped into these three clusters? Discuss the differences in symptom presentation between the three personality clusters.

- Create a chart identifying each of the disorders among the three clusters. Be sure to include personality characteristics of each disorder. It is important to find characteristics unique to each personality disorder to aid in their identification.

13.2. Epidemiology

Section Learning Objectives

- Describe the epidemiology of Cluster A personality disorders.

- Describe the epidemiology of Cluster B personality disorders.

- Describe the epidemiology of Cluster C personality disorders.

13.2.1. Cluster A

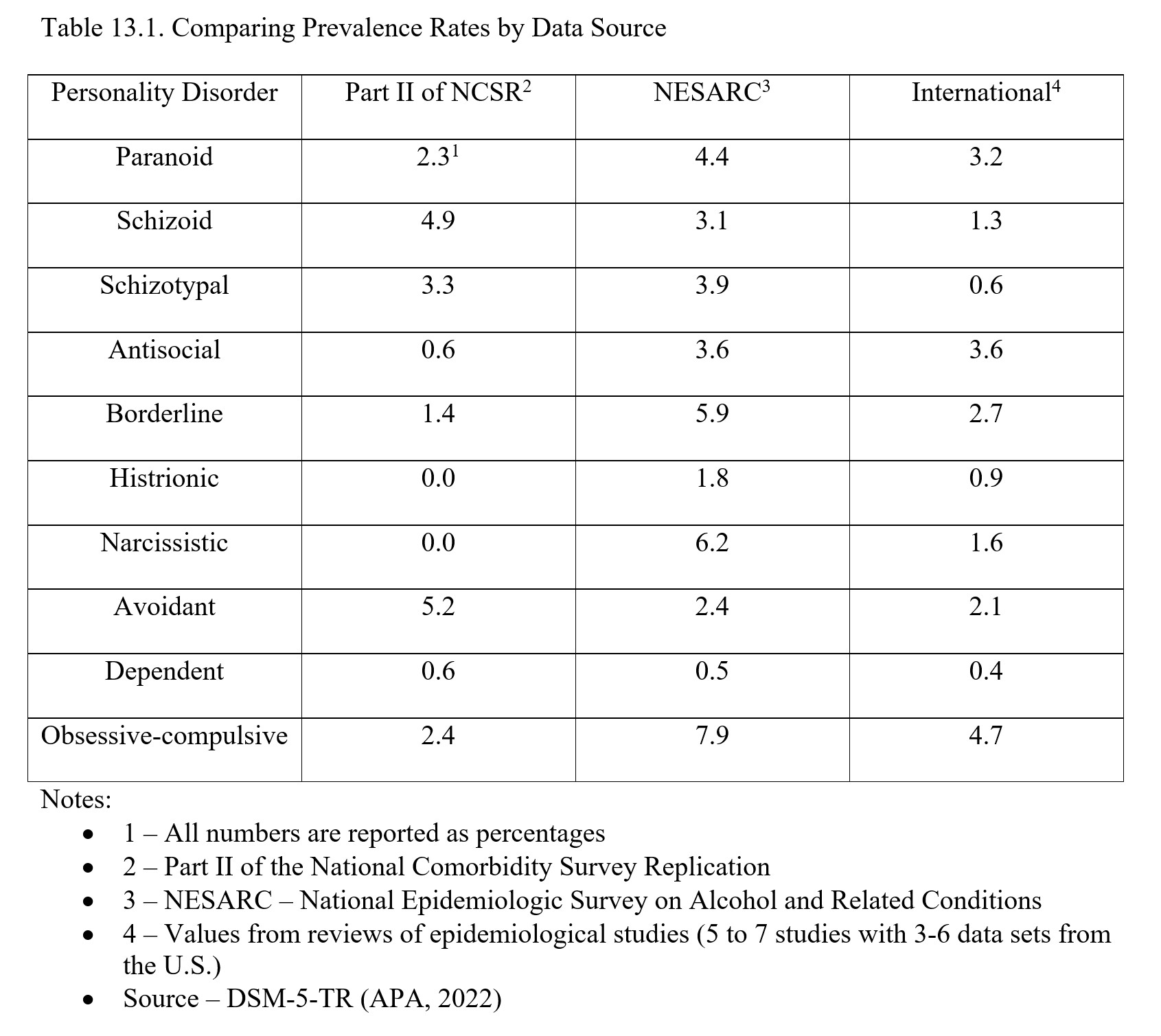

Disorders within Cluster A have a prevalence rate of around 2-5%. More specifically, according to Part II of the National Comorbidity Survey Replication, the estimated prevalence of paranoid personality disorder was 2.3%, schizoid personality disorder was 4.9%, and schizotypal personality disorder was 3.3%. Schizotypal personality disorder has been found to be more common in men while research on schizoid personality disorder leans to no gender difference in prevalence. As for paranoid personality disorder, it appears to be more common in men though the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related conditions found it to be more common in women (APA, 2022).

13.2.2. Cluster B

Using Part II of the National Comorbidity Survey Replication, it was found that for Cluster B personality disorders prevalence rates were: 0.6% for antisocial, 1.4% for borderline, 0.0% for histrionic, and 0.0% for narcissistic. It should be noted that the prevalence of histrionic personality disorder was 1.8% and narcissistic was 6.2% in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions.

As for sex-and gender-related differences, antisocial personality disorder is three times more common in men and they present with irritability/aggression and reckless disregard for the safety of others more often than women. Borderline personality disorder is more common among women in clinical samples while community samples show no difference in prevalence, likely due to the tendency of women to seek help leading them to clinical settings. Histrionic personality disorder is more predominant in females in clinical settings, though some studies using structured assessments point to no difference in prevalence rates across the genders. Narcissistic personality disorder occurs more in men than women.

13.2.3. Cluster C

Using Part II of the National Comorbidity Survey Replication, it was found that for Cluster C personality disorders prevalence rates were: 5.2% for avoidant, 0.6% for dependent, and 2.4% for OCPD. Women are more likely to be diagnosed with avoidant and dependent personality disorders while OCPD appears to be equally prevalent in women and men.

For expanded information on the prevalence of the various personality disorders from the DSM-5-TR, please see Table 13. 1 below.

Key Takeaways

You should have learned the following in this section:

- Prevalence rates of Cluster A personality disorders range from 2% to 5% with schizotypal being more common in men and there being no difference in schizoid and conflicting evidence for paranoid.

- Prevalence rates of Cluster B personality disorders range from 0.0% to 1.4% and antisocial and narcissistic are more common in men with borderline and histrionic being more common in women, in general.

- Prevalence rates of Cluster C personality disorders range from 0.6% to 5.2% with women being more likely to be diagnosed with avoidant and dependent personality disorders and OCPD appearing to be equally prevalent in women and men.

Section 13.2 Review Questions

- What is the difference in prevalence rates across the three clusters? Are there any trends among gender?

- Identify the most commonly occurring personality disorder. Which is the least common?

13.3. Comorbidity

Section Learning Objectives

- Describe the comorbidity of personality disorders.

Among the most common comorbid diagnoses with personality disorders are mood disorders, anxiety disorders, and substance abuse disorders (Lenzenweger, Lane, Loranger, & Kessler, 2007). A large meta-analysis exploring the data on the comorbidity of major depressive disorder and personality disorders indicated a high diagnosis of major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, and dysthymia (Friborg, Martinsen, Martinussen, Kaiser, Overgard, & Rosenvinge, 2014). Further exploration of major depressive disorder suggested the lowest rate of diagnosis in Cluster A disorders, higher rate in Cluster B disorders, and the highest rate in Cluster C disorders. While the relationship between bipolar disorder and personality disorders has not been consistently clear, the most recent findings report a high comorbidity between Cluster B personality disorders, with the exception of OCPD (which is in Cluster C), which had the highest comorbidity rate than any other personality disorder. Overall analysis of dysthymia suggested that it is the most diagnosed depressive disorder among all personality disorders.

A more detailed analysis exploring the prevalence rates of the four main anxiety disorders (generalized anxiety disorder, specific phobia, social phobia, and panic disorder) among individuals with various personality disorders found a clear relationship specific to personality disorders and anxiety disorders (Skodol, Geier, Grant, & Hasin, 2014). More specifically, individuals diagnosed with borderline and schizotypal personality disorders were found to have an additional diagnosis of one of the four main anxiety disorders. Individuals with narcissistic personality disorder were more likely to be diagnosed with generalized anxiety disorder and panic disorder; schizoid and avoidant personality disorders reported significant rates of generalized anxiety disorder; avoidant personality disorder had a higher diagnosis rate of social phobia. Substance use disorders occur less frequently across the ten personality disorders but are most common in individuals diagnosed with antisocial, borderline, and schizotypal personality disorders (Grant et al., 2015). Schizotypal personality disorder is also comorbid with brief psychotic disorder, schizophreniform disorder, delusional disorder, and schizophrenia while borderline is additionally comorbid with eating disorders, PTSD, and ADHD (APA, 2022).

Key Takeaways

You should have learned the following in this section:

- Mood disorders, anxiety disorders, and substance abuse disorders have a high comorbidity with personality disorders.

- Substance abuse disorders occur less frequently across the ten personality disorders but when they do, are comorbid with antisocial, borderline, and schizotypal personality disorders.

Section 13.3 Review Questions

- With what other disorders are personality disorders comorbid?

13.4. Etiology

Section Learning Objectives

- Describe the biological causes of personality disorders.

- Describe the psychological causes of personality disorders.

- Describe the social causes of personality disorders.

Research regarding the development of personality disorders is limited compared to that of other mental health disorders. The following is a general overview of contributing factors to personality disorders. While there is some research lending itself to specific causes of specific personality disorders, the overall contribution of biological, psychological, and social factors will be reviewed.

13.4.1. Biological

Research across the personality disorders suggests some underlying biological or genetic component; however, identification of specific mechanisms have not been identified in most disorders, except for those below. Because of this lack of concrete evidence, researchers argue that it is difficult to determine what role genetics plays into the development of these disorders compared to that of environmental influences. Therefore, while there is likely a biological predisposition to personality disorders, exact causes cannot be determined at this time.

Research on the development of schizotypal personality disorder has identified similar biological causes to that of schizophrenia—high activity of dopamine and enlarged brain ventricles (Lener et al., 2015). Similar differences in neuroanatomy may explain the high similarity of behaviors in both schizophrenia and schizotypal personality disorder.

Surprisingly, antisocial personality disorder and borderline personality disorder also have similar neurological changes. More specifically, individuals with both disorders reportedly show deficits in serotonin activity (Thompson, Ramos, & Willett, 2014). These low levels of serotonin activity in combination with deficient functioning of the frontal lobes—particularly the prefrontal cortex which is used in planning, self-control, and decision making—as well as an overly reactive amygdala, may explain the impulsive and aggressive nature of both antisocial and borderline personality disorder (Stone, 2014).

13.4.2. Psychological

Psychodynamic, cognitive, and behavioral theories are among the most common psychological models used to explain the development of personality disorders. Although much is still speculation, the following are general etiological views with regards to each specific theory.

13.4.2.1. Psychodynamic. The psychodynamic theory places a large emphasis on negative early childhood experiences and how these experiences impact an individual’s inability to establish healthy relationships in adulthood. More specifically, individuals with personality disorders report higher levels of childhood stress, such as living in impoverished environments, exposure to domestic violence, and experiencing repeated maltreatment (Kumari et al., 2014). Additionally, high levels of childhood neglect and parental rejection are also observed in personality disorder patients, with early parental loss and rejection leading to fears of abandonment throughout an individual’s life (Newnham & Janca, 2014; Roepke & Varter, 2014; Caligor & Clarkin, 2010).

Psychodynamic theorists believe that maltreatment in early childhood has the potential to negatively affect an individual’s sense of self and their perception of others, leading to the development of a personality disorder. For example, an individual who was neglected as a young child and deprived of love may report a lack of trust in others as an adult, a characteristic of antisocial personality disorder (Meloy & Yakeley, 2010). Difficulty trusting others or beliefs that they are unable to be loved may also impact one’s ability or desire to establish social relationships, as seen in many personality disorders, particularly schizoid. Because of these early childhood deficits, individuals may also overcompensate in their relationships to convince themselves that they are worthy of love and affection (Celani, 2014). Conversely, individuals may respond to their early childhood experiences by becoming emotionally distant, using relationships as a sense of power and destructiveness.

13.4.2.2. Cognitive. While psychodynamic theory emphasizes early childhood experiences, cognitive theorists focus on the maladaptive thought patterns and cognitive distortions displayed by those with personality disorders. Overall deficiencies in thinking can lead individuals with personality disorders to develop inaccurate perceptions of others (Beck, 2015). These dysfunctional beliefs likely originate from the interaction between a biological predisposition and undesirable environmental experiences. Maladaptive thought patterns and strategies are strengthened during aversive life events as a protective mechanism and ultimately come together to form patterns of behavior displayed in personality disorders (Beck, 2015).

Cognitive distortions such as dichotomous thinking, also known as all-or-nothing thinking, are observed in several personality disorders. More specifically, dichotomous thinking explains rigidity and perfectionism in OCPD, and the lack of self-sufficiency among individuals with dependent and borderline personality disorders (Weishaar & Beck, 2006). Discounting the positive also explains the underlying mechanisms for avoidant personality disorder (Weishaar & Beck, 2006). For example, individuals who have been routinely criticized or rejected during childhood may have difficulty accepting positive feedback from others, expecting only to receive rejection and harsh criticism. In fact, they may employ these misattributions to positive feedback to support their ongoing theory that they are constantly rejected and criticized by others.

13.4.2.3. Behavioral. Behavioral theorists apply three major theories to explain the development of personality disorders: modeling, reinforcement, and lack of social skills. In modeling, an individual learns maladaptive social patterns and behaviors by directly observing family members engaging in similar behaviors (Gaynor & Baird, 2007). While we cannot discredit the biological component of the familial influence, research does support an additive modeling or imitating component to the development of personality disorders, especially antisocial personality disorder (APA, 2022).

Reinforcement, or rewarding of maladaptive behaviors is also observed in the development of many personality disorders. Parents may unintentionally reward aggressive behaviors by giving in to a child’s desires to cease the situation or prevent escalation of behaviors. When this is done repeatedly over time, children (and later as adults) continue with these maladaptive behaviors as they are effective in gaining their needs and wants. On the other side, there is some speculation that excessive reinforcement or praise during childhood may contribute to the grandiose sense of self observed in individuals with narcissistic personality disorder (Millon, 2011).

Finally, failure to develop normal social skills may explain the development of some personality disorders, such as avoidant personality disorder (Kantor, 2010).

13.4.3. Social

13.4.3.1. Family dysfunction. High levels of psychological and social dysfunction within families have also been identified as contributing factors to the development of personality disorders. High levels of poverty, unemployment, family separation, and witnessing domestic violence are routinely observed in individuals diagnosed with personality disorders (Paris, 1996). While formalized research has yet to explore the relationship between SES and personality disorders fully, correlational studies suggest a link between poverty, unemployment, and poor academic achievement with increased levels of personality disorder diagnoses (Alwin, 2006).

13.4.3.2. Childhood maltreatment. Childhood maltreatment is among the most influential argument for the development of personality disorders in adulthood. Individuals with personality disorders often struggle with a sense of self and the ability to relate to others—something that is generally developed during the first four to six years of a child’s life, and it is affected by the emotional environment in which that child was raised. This sense of self is the mechanism in which individuals view themselves within their social context, while also informing attitudes and expectations of others. A child who experiences significant maltreatment, whether it be through neglect or physical, emotional, or sexual abuse, is at-risk for an underdeveloped or absent sense of self. Due to the lack of affection, discipline, or autonomy during childhood, these individuals are unable to engage in appropriate relationships as adults as seen across the spectrum of personality disorders.

Another way childhood maltreatment contributes to personality disorders is through the emotional bonds or attachments developed with primary caregivers. John Bowlby thoroughly researched the relationship between attachment and emotional development as he explored the need for affection in Harlow monkeys (Bowlby, 1998). Based on Bowlby’s research, four attachment styles have been identified: secure, anxious, ambivalent, and disorganized. While securely attached children generally do not develop personality disorders, those with anxious, ambivalent, and disorganized attachment are at an increased risk of developing various disorders. More specifically, those with an anxious attachment are at-risk for developing internalizing disorders, ambivalent are at-risk for developing externalizing disorders, and disorganized are at-risk for dissociative symptoms and personality-related disorders (Alwin, 2006).

Key Takeaways

You should have learned the following in this section:

- Biological causes of personality disorders have not been identified in most disorders, the exception being schizotypal which has similar biological causes as schizophrenia and antisocial and borderline personality disorders which have similar neurological changes.

- Psychological causes of personality disorders include negative early childhood experiences; maladaptive thought patterns and cognitive distortions; and modeling, reinforcement, and lack of social skills.

- Social causes of personality disorders include high levels of psychological and social dysfunction within families and maltreatment.

Section 13.4 Review Questions

- What personality disorders are most explained by the biological model?

- How does the psychodynamic model explain the development of personality disorders?

- What cognitive distortions are most discussed with respect to personality disorders?

- What are the three behavioral theories used to explain the development of personality disorders?

- Discuss the role of attachment and how theorists have used it to explain the development of personality disorders.

13.5. Treatment

Section Learning Objectives

- Describe treatment options for personality disorders.

13.5.1. Cluster A

Individuals with personality disorders within Cluster A often do not seek out treatment as they do not identify themselves as someone who needs help (Millon, 2011). Of those that do seek treatment, the majority do not enter it willingly. Furthermore, due to the nature of these disorders, individuals in treatment often struggle to trust the clinician as they are suspicious of the clinician’s intentions (paranoid and schizotypal personality disorder) or are emotionally distant from the clinician as they do not have a desire to engage in treatment due to lack of overall emotion (schizoid personality disorder; Kellett & Hardy, 2014, Colli, Tanzilli, Dimaggio, & Lingiardi, 2014). Because of this, treatment is known to move very slowly, with many patients dropping out before any resolution of symptoms.

When patients are enrolled in treatment, cognitive-behavioral strategies are most commonly used with the primary intention of reducing anxiety-related symptoms. Additionally, attempts at cognitive restructuring—both identifying and changing maladaptive thought patterns—are also helpful in addressing the misinterpretations of other’s words and actions, particularly for individuals with paranoid personality disorder (Kellett & Hardy, 2014). Schizoid personality disorder patients may engage in CBT techniques to help experience more positive emotions and more satisfying social experiences, whereas the goal of CBT for schizotypal personality disorder is to evaluate unusual thoughts or perceptions objectively and to ignore the inappropriate thoughts (Beck & Weishaar, 2011). Finally, behavioral techniques such as social-skills training may also be implemented to address ongoing interpersonal problems displayed in the disorders.

13.5.2. Cluster B

13.5.2.1. Antisocial personality disorder. Treatment options for antisocial personality disorder are limited and generally not effective (Black, 2015). Like Cluster A disorders, many individuals are forced to participate in treatment, thus impacting their ability to engage in and continue with treatment. Cognitive therapists have attempted to address the lack of morality and encourage patients to think about the needs of others (Beck & Weishaar, 2011).

13.5.2.2. Borderline personality disorder. Borderline personality disorder is the one personality disorder with an effective treatment option—Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (DBT). DBT is a form of cognitive-behavioral therapy developed by Marsha Linehan (Linehan, Armstrong, Suarez, Allmon, & Heard, 1991). There are four main goals of DBT: reduce suicidal behavior, reduce therapy interfering behavior, improve quality of life, and reduce post-traumatic stress symptoms.

Within DBT, five main treatment components collectively help to reduce harmful behaviors (i.e., self-mutilation and suicidal behaviors) and replace them with practical, life-enhancing behaviors (Gonidakis, 2014). The first component is skills training. Generally performed in a group therapy setting, individuals engage in mindfulness, distress tolerance, interpersonal effectiveness, and emotion regulation. Second, individuals focus on enhancing motivation and applying skills learned in the previous component to specific challenges and events in their everyday life. The third, and often the most distinctive aspect of DBT, is the use of telephone and in vivo coaching for DBT patients from the DBT clinical team. It is not uncommon for patients to have the cell phone number of their clinician for 24/7 availability of in-the-moment support. The fourth component, case management, consists of allowing the patient to become their own “case manager” and effectively use the learned DBT techniques to problem-solve ongoing issues. Within this component, the clinician will only intervene when absolutely necessary. Finally, the consultation team, is a service for the clinicians providing the DBT treatment. Due to the high demands of borderline personality disorder patients, the consultation team offers support to the providers in their work to ensure they remain motivated and competent in DBT principles to provide the best treatment possible.

Support for the effectiveness of DBT in borderline personality disorder patients has been implicated in several randomized control trials (Harned, Korslund, & Linehan, 2014; Neacsiu, Eberle, Kramer, Wisemeann, & Linehan, 2014). More specifically, DBT has shown to significantly reduce suicidality and self-harm behaviors in those with borderline personality disorders. Additionally, the drop-out rates for treatment are extremely low, suggesting that patients value the treatment components and find them useful in managing symptoms.

13.5.2.3. Histrionic personality disorder. Individuals with histrionic personality disorder are more likely to seek out treatment than other personality disorder patients. Unfortunately, due to the nature of the disorder, they are very difficult patients to treat as they are quick to employ their demands and seductiveness within the treatment setting. The overall goal for the treatment of histrionic personality disorder is to help the patient identify their dependency and become more self-reliant. Cognitive therapists utilize techniques to help patients change their helpless beliefs and improve problem-solving skills (Beck & Weishaar, 2011).

13.5.2.4. Narcissistic personality disorder. Of all the personality disorders, narcissistic personality disorder is among the most difficult to treat (with maybe the exception of antisocial personality disorder). Most individuals with narcissistic personality disorder only seek out treatment for those disorders secondary to their personality disorder, such as depression (APA, 2022). The focus of treatment is to address the grandiose, self-centered thinking, while also trying to teach patients how to empathize with others (Beck & Weishaar, 2014).

13.5.3. Cluster C

While many individuals within avoidant and OCPD personality disorders seek out treatment to address their anxiety or depressive symptoms, it is often difficult to keep them in treatment due to distrust or fear of rejection from the clinician. Treatment goals for avoidant personality disorder are similar to that of social anxiety disorder. CBT techniques, such as identifying and challenging distressing thoughts, have been effective in reducing anxiety-related symptoms (Weishaar & Beck, 2006). Specific to OCPD, cognitive techniques aimed at changing dichotomous thinking, perfectionism, and chronic worrying help manage symptoms of OCPD. Behavioral treatments such as gradual exposure to various social settings, along with a combination of social skills training, have been shown to improve individuals’ confidence prior to engaging in social outings when treating avoidant personality disorder (Herbert, 2007). Antianxiety and antidepressant medications commonly used to treat anxiety disorders have also been used with minimal efficacy; furthermore, symptoms resume as soon as the medication is discontinued.

Unlike other personality disorders where individuals are skeptical of the clinician, individuals with dependent personality disorder try to place obligations of their treatment on the clinician. Therefore, one of the main treatment goals for dependent personality disorder patients is to teach them to accept responsibility for themselves, both in and outside of treatment (Colli, Tanzilli, Dimaggio, & Lingiardi, 2014). Cognitive strategies such as challenging and changing thoughts on helplessness and inability to care for oneself have been minimally effective in establishing independence. Additionally, behavioral techniques such as assertiveness training have also shown some promise in teaching individuals how to express themselves within a relationship. Some argue that family or couples therapy would be particularly helpful for those with dependent personality disorder due to the relationship between the patient and another person being the primary issue; however, research on this treatment method has not yielded consistently positive results (Nichols, 2013).

Key Takeaways

You should have learned the following in this section:

- Individuals with a Cluster A personality disorder do not often seek treatment and when they do, struggle to trust the clinician (paranoid and schizotypal) or are emotionally distant from the clinician (schizoid). When in treatment, cognitive restructuring and cognitive behavioral strategies are used.

- In terms of Cluster B, treatment options for antisocial are limited and generally not effective, borderline responds well to dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT), histrionic patients seek out help but are difficult to work with, and finally narcissistic are the most difficult to treat.

- For Cluster C, cognitive techniques aid with OCPD while gradual exposure to various social settings and social skills training help with avoidant. Clinicians use cognitive strategies to challenge thoughts on helplessness in patients with dependent personality disorder.

Section 13.5 Review Questions

- What is the process in Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (DBT)? What does the treatment entail? What disorders are treated with DBT?

- Given the difference in personality characteristics between the three clusters, how are the suggested treatment options different between cluster A, B, and C?

Module Recap

Module 13 covered three clusters of personality disorders: Cluster A, which includes paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal; Cluster B, which includes antisocial, borderline, histrionic, and narcissistic; and Cluster C which includes avoidant, dependent, and obsessive-compulsive. We also covered the clinical description, epidemiology, comorbidity, etiology, and treatment of personality disorders.

3rd edition