3rd edition as of July 2023

Module Overview

In Module 12, we will discuss matters related to schizophrenia spectrum disorders to include their clinical presentation, epidemiology, comorbidity, etiology, and treatment options. Our discussion will consist of schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, schizoaffective disorder, and delusional disorder. Be sure you refer Modules 1-3 for explanations of key terms (Module 1), an overview of the various models to explain psychopathology (Module 2), and descriptions of the therapies (Module 3).

Module Outline

Module Learning Outcomes

- Describe how schizophrenia spectrum disorders present.

- Describe the epidemiology of schizophrenia spectrum disorders.

- Describe comorbidity in relation to schizophrenia spectrum disorders.

- Describe the etiology of schizophrenia spectrum disorders.

- Describe treatment options for schizophrenia spectrum disorders.

12.1. Clinical Presentation

Section Learning Objectives

- List and describe distinguishing features that make up the clinical presentation of schizophrenia spectrum disorders.

- Describe how schizophrenia presents.

- Describe how schizophreniform disorder presents.

- Describe how schizoaffective disorder presents.

- Describe how delusional disorder presents.

12.1.1. The Clinical Presentation of Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders

The schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders are defined by one of the following main symptoms: delusions, hallucinations, disorganized thinking (speech), disorganized or abnormal motor behavior, and negative symptoms. Individuals diagnosed with a schizophrenia spectrum disorder experience psychosis, which is defined as a loss of contact with reality. Psychosis episodes make it difficult for individuals to perceive and respond to environmental stimuli, causing a significant disturbance in everyday functioning. While there are a vast number of symptoms displayed in schizophrenia spectrum disorders, presentation of symptoms varies greatly among individuals, as there are rarely two cases similar in presentation, triggers, course, or responsiveness to treatment.

12.1.1.1. Delusions. Delusions are “fixed beliefs that are not amenable to change in light of conflicting evidence” (APA, 2022, pp. 101). This means that despite evidence contradicting one’s thoughts, the individual is unable to distinguish their thoughts from reality. The inability to identify thoughts as delusional is likely likely due to a lack of insight. There are a wide range of delusions that are seen in the schizophrenia related disorders to include:

- Delusions of grandeur– belief they have exceptional abilities, wealth, or fame; belief they are God or other religious saviors

- Delusions of control– belief that others control their thoughts/feelings/actions

- Delusions of thought broadcasting– belief that one’s thoughts are transparent and everyone knows what they are thinking

- Delusions of persecution– belief they are going to be harmed, harassed, plotted or discriminated against by either an individual or an institution; it is the most common delusion (Arango & Carpenter, 2010)

- Delusions of reference– belief that specific gestures, comments, or even larger environmental cues are directed directly to them

- Delusions of thought withdrawal– belief that one’s thoughts have been removed by another source

It is believed that the presentation of the delusion is primarily related to the social, emotional, educational, and cultural background of the individual (Arango & Carpenter, 2010). For example, an individual with schizophrenia who comes from a highly religious family is more likely to experience religious delusions (delusions of grandeur) than another type of delusion.

12.1.1.2. Hallucinations. Hallucinations are “perception-like experiences that occur without an external stimulus” (APA, 2022, pg. 102). They can occur in any of the five senses: hearing (auditory hallucinations), seeing (visual hallucinations), smelling (olfactory hallucinations), touching (tactile hallucinations), and tasting (gustatory hallucinations). Additionally, they can occur in a single modality or present across a combination of modalities (e.g., having auditory and visual hallucinations). For the most part, individuals recognize that their hallucinations are not real and attempt to engage in normal behavior while simultaneously combating ongoing hallucinations.

According to various research studies, nearly half of all patients with schizophrenia report auditory hallucinations, 15% report visual hallucinations, and 5% report tactile hallucinations (DeLeon, Cuesta, & Peralta, 1993). Among the most common types of auditory hallucinations are voices talking to the patient or various voices talking to one another. Generally, these hallucinations are not attributable to any one person that the individual knows. They are usually clear, objective, and definite (Arango & Carpenter, 2010). Additionally, the auditory hallucinations can be pleasurable, providing comfort to the patient; however, in other individuals, the auditory hallucinations can be unsettling as they produce commands or malicious intent.

12.1.1.3. Disorganized thinking (Speech). Among the most common cognitive impairments displayed in patients with schizophrenia are disorganized thoughts, communication, and speech. More specifically, thoughts and speech patterns may appear to be circumstantial or tangential. For example, patients may give unnecessary details in response to a question before they finally produce the desired response. While the question is eventually answered in circumstantial speech patterns, in tangential speech patterns the patient never reaches the point. Another common cognitive symptom is speech incoherence or word salad, where speech is “nearly incomprehensible and resembles receptive aphasia in its linguistic disorganization” (APA, 2022, pg. 102). Derailment, or the illogical connection in a chain of thoughts, is another common type of disorganized thinking. Although not always, derailment is often seen in illogicality, or the tendency to provide bizarre explanations for things.

These types of distorted thought patterns are often related to concrete thinking. That is, the individual is focused on one aspect of a concept or thing and neglects all other aspects. This type of thinking makes treatment difficult as individuals lack insight into their illness and symptoms.

12.1.1.4. Disorganized/abnormal motor behavior. These symptoms manifest as childlike “silliness” to unpredictable agitation. Catatonic behavior, the decreased or complete lack of reactivity to the environment, is among the most commonly seen grossly disorganized motor behavior in schizophrenia. There runs a range of catatonic behaviors from negativism (resistance to instruction); mutism or stupor (complete lack of verbal and motor responses); rigidity (maintaining a rigid or upright posture while resisting efforts to be moved); or posturing (holding odd, awkward postures for long periods). There is one type of catatonic behavior, catatonic excitement, where the individual experiences hyperactivity of motor behavior, in a seemingly excited or delirious way. Other features include repeated stereotyped movements, staring, grimacing, and the echoing of speech (APA, 2022, pg. 102).

12.1.1.5. Negative symptoms. Up until this point, all the symptoms can be categorized as positive symptoms, or symptoms that are an over-exaggeration of normal brain processes; these symptoms are also new to the individual. The final diagnostic criterion is negative symptoms, which are defined as the inability or decreased ability to initiate actions, speech, express emotion, or feel pleasure (Barch, 2013). Negative symptoms often present before positive symptoms and remain once positive symptoms remit. Because of their prevalence through the course of the disorder, they are also more indicative of prognosis, with more negative symptoms suggesting a poorer prognosis. The poorer prognosis may be explained by the lack of effectiveness antipsychotic medications have in addressing negative symptoms (Kirkpatrick, Fenton, Carpenter, & Marder, 2006). There are six main types of negative symptoms seen in patients with schizophrenia. Such symptoms include:

- Diminished emotional expression – Reduction in emotional expression; reduced display of emotional expression

- Alogia – Poverty of speech or speech content

- Anhedonia – Inability to experience pleasure

- Asociality – Lack of interest in social relationships

- Avolition – Lack of motivation for goal-directed behavior

12.1.2. Schizophrenia

As stated above, the hallmark symptoms of schizophrenia include the presentation of at least two of the following during a one month period: delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech, disorganized/abnormal behavior, or negative symptoms. These symptoms create significant impairment in an individual’s ability to engage in normal daily functioning such as work, school, relationships with others, or self-care, and continuous signs of the disturbance persist for at least 6 months. It should be noted that the presentation of schizophrenia varies significantly among individuals, as it is a heterogeneous clinical syndrome (APA, 2022).

While the presence of symptoms must persist for a minimum of 6 months to meet the criteria for a schizophrenia diagnosis, it is not uncommon to have prodromal symptoms that precede the active phase of the disorder and residual symptoms that follow it. These prodromal and residual symptoms are “subthreshold” forms of psychotic symptoms that do not cause significant impairment in functioning, with the exception of negative symptoms (Lieberman et al., 2001). Due to the severity of psychotic symptoms, mood disorder symptoms are also common among individuals with schizophrenia; however, these mood symptoms are distinct from a mood disorder diagnosis in that psychotic features will exist beyond the remission of depressive symptoms.

12.1.3. Schizophreniform Disorder

Schizophreniform disorder is similar to schizophrenia, except for the length of presentation of symptoms. Schizophreniform disorder is considered an “intermediate” disorder between schizophrenia and brief psychotic disorder as the symptoms are present for at least one month but not longer than six months. Schizophrenia symptoms must be present for at least six months and a brief psychotic disorder is diagnosed when symptoms are present for less than one month. Approximately two-thirds of individuals who are initially diagnosed with schizophreniform disorder will have symptoms that last longer than six months, at which time their diagnosis is changed to schizophrenia (APA, 2022).

Another key distinguishing feature of schizophreniform disorder is the lack of criteria related to impaired functioning. While many individuals with schizophreniform disorder do display impaired functioning, it is not essential for diagnosis. Finally, any major mood episodes—either depressive or manic— that are present concurrently with the psychotic features must only be present for a short time, otherwise a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder may be more appropriate (APA, 2022).

Making Sense of the Disorders

In relation to schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders, note the following:

- Diagnosis brief psychotic disorder …… if symptoms have been present for less than one month

- Diagnosis schizophreniform disorder …… if symptoms have been present for at least one month but not longer than six months

- Diagnosis schizophrenia … if the symptoms have been present for at least six months

12.1.4. Schizoaffective Disorder

Schizoaffective disorder is characterized by the psychotic symptoms included in schizophrenia and a concurrent uninterrupted period of a major mood episode—either a major depressive or manic episode. It should be noted that because the loss of interest in pleasurable activities is a common symptom of schizophrenia, to meet the criteria for a depressive episode within schizoaffective disorder, the individual must present with a pervasive depressed mood (APA, 2022). While schizophrenia and schizophreniform disorder do not have a significant mood component, schizoaffective disorder requires the presence of a depressive or manic episode for the majority, if not the total duration of the disorder. While psychotic symptoms are sometimes present in depressive episodes, they often remit once the depressive episode is resolved. For individuals with schizoaffective disorder, psychotic symptoms should continue for at least two weeks in the absence of a major mood disorder (APA, 2022). This is the key distinguishing feature between schizoaffective disorder and major depressive disorder with psychotic features.

12.1.5. Delusional Disorder

As suggestive of its title, delusional disorder requires the presence of at least one delusion that lasts for at least one month in duration. It is important to note that if an individual experiences hallucinations, disorganized speech, disorganized or catatonic behavior, or negative symptoms—in addition to delusions—they should not be diagnosed with delusional disorder as their symptoms are more aligned with a schizophrenia diagnosis. Unlike most other schizophrenia-related disorders, daily functioning is not overly impacted due to the delusions. Additionally, if symptoms of depressive or manic episodes present during delusions, they are typically brief compared to the duration of the delusions.

The DSM-V-TR (APA, 2022) has identified five main subtypes of delusional disorder to better categorize the symptoms of the individual’s disorder. When making a diagnosis of delusional disorder, one of the following modifiers (in addition to mixed presentation) is included. Erotomanic delusion occurs when an individual reports a delusion of another person being in love with them. Generally speaking, the individual whom the convictions are about is of higher status, such as a celebrity. Grandiose delusion involves the conviction of having great talent or insight. Occasionally, patients will report they have made an important discovery that benefits the general public. Grandiose delusions may also take on religious affiliation, as people believe they are prophets or even God. Jealous delusion revolves around the conviction that one’s spouse or partner is/has been unfaithful. While many individuals may have this suspicion at some point in their relationship, a jealous delusion is much more extensive and generally based on incorrect inferences that lack evidence. Persecutory delusion involves the individual believing that they are being conspired against, spied on, followed, poisoned or drugged, maliciously maligned, harassed, or obstructed in pursuit of their long-term goals (APA, 2022). Of all subtypes of delusional disorder, those experiencing persecutory delusions are the most at risk of becoming aggressive or hostile, likely due to the persecutory nature of their distorted beliefs. Finally, somatic delusion involves delusions regarding bodily functions or sensations. While these delusions can vary significantly, the most common beliefs are that the individual emits a foul odor despite attempts to rectify the smell; there is an infestation of insects on the skin; or that they have an internal parasite (APA, 2022). If no one delusion predominates, the mixed type specifier is used and if the dominant delusional belief cannot be clearly determined, use the unspecified type specifier. A separate specifier is used when the content of the delusions are deemed bizarre or implausible, not understandable, and not derived from ordinary life experience.

Key Takeaways

You should have learned the following in this section:

- Schizophrenia spectrum disorders are characterized by delusions, hallucinations, disorganized thinking (speech), disorganized or abnormal motor behavior, and negative symptoms.

- Delusions are beliefs that do not change even when conflicting evidence is presented and can be of grandeur, control, thought broadcasting, persecution, reference, and thought withdrawal.

- Hallucinations occur in any sense modality and most individuals recognize that they are not real.

- Disorganized thinking, abnormal motor behavior, catatonic behavior, and negative symptoms such as affective flattening, alogia, anhedonia, asociality, and avolition are also common to schizophrenia spectrum disorders.

- Schizophrenia is characterized by delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech, disorganized/abnormal behavior, or negative symptoms lasting six months.

- Schizophreniform disorder is considered an “intermediate” disorder between schizophrenia and brief psychotic disorder as the symptoms are present for at least one month but not longer than six months.

- Schizoaffective disorder is characterized by the psychotic symptoms included in schizophrenia and a concurrent uninterrupted period of a major mood episode—either a depressive or manic episode.

- Delusional disorder requires the presence of at least one delusion that lasts for at least one month in duration to include erotomanic, grandiose, jealous, persecutory, and somatic.

Section 12.1 Review Questions

- What are the four positive symptoms identified in a schizophrenia diagnosis? Define and identify their difference.

- What is meant by negative symptoms? What are the negative symptoms observed in schizophrenia related disorders?

- Identify diagnostic differences between schizophrenia, schizophreniform, schizoaffective, and delusional disorders.

12.2. Epidemiology

Section Learning Objectives

- Describe the epidemiology of schizophrenia spectrum disorders.

Schizophrenia occurs in approximately 0.3%-0.7% of the general population (APA, 2022). There is some discrepancy in rates of diagnosis between genders; these differences appear to be related to the emphasis of various symptoms. For example, men typically present with more negative symptoms, whereas women present with more affect-laden symptoms. Despite gender differences in the presentation of symptoms, there appears to be an equal risk for both genders to develop the disorder.

Schizophrenia typically occurs between late teens and mid-30s, with the onset of the disorder slightly earlier for males than females (APA, 2022). Earlier onset of the disorder is generally predictive of a worse overall prognosis. Onset of symptoms is typically gradual, with initial symptoms presenting similarly to depressive disorders; however, some individuals will present with an abrupt presentation of the disorder. Negative symptoms appear to be more predictive of prognosis than other symptoms. This may be due to negative symptoms being the most persistent, and therefore, most difficult to treat. Overall, an estimated 13.5% of individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia meet recovery criteria, according to one meta-analysis of 50 studies of individuals with broadly defined schizophrenia (APA, 2022).

Schizoaffective disorder, schizophreniform disorder, and delusional disorder prevalence rates are all significantly less than that of schizophrenia, occurring in 0.2% to 0.3% of the general population. While schizoaffective disorder is diagnosed more in females than males (similar to schizophrenia but using the less stringent DSM-IV criteria), schizophreniform and delusional disorder appear to be diagnosed equally between genders (APA, 2022).

Key Takeaways

You should have learned the following in this section:

- Less than 1% of the general population is diagnosed with schizophrenia and 13.5% of these people fully recovery from the disorder.

- Both genders have an equal risk of developing schizophrenia while men typically display more negative symptoms while women present with more affect-laden symptoms.

- Schizoaffective disorder, schizophreniform disorder, and delusional disorder have prevalence rates between 0.2 to 0.3%.

Section 12.2 Review Questions

- Discuss the different prevalence rates across the schizophrenia related disorders. Are there differences among the disorders? Between genders?

- Are there differences in prevalence rates depending on symptom presentations? If so, what?

12.3. Comorbidity

Section Learning Objectives

- Describe the comorbidity of schizophrenia spectrum disorders.

There is a high comorbidity between schizophrenia and substance abuse disorder and there is some evidence to suggest that the use of various substances (particularly marijuana) may place an individual at an increased risk of developing schizophrenia if the genetic predisposition is also present (see diathesis-stress model below; Corcoran et al., 2003). Additionally, there appears to be comorbidity with anxiety-related disorders, specifically panic disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder, among individuals with schizophrenia than compared to the general public. Schizotypal or paranoid personality disorder sometimes precede the onset of schizophrenia. About 5-6% of individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia die by suicide, about 20% have attempted suicide on at least one occasion, and many more have significant suicidal ideation.

It should also be noted that individuals diagnosed with a schizophrenia-related disorder are also at an increased risk for associated medical conditions such as weight gain, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular and pulmonary disease (APA, 2022). This predisposition to various medical conditions is likely related to medications and poor lifestyle choices, and also place individuals at risk for a reduced life expectancy.

Schizoaffective disorder is comorbid with substance use disorders and anxiety disorders. Metabolic syndrome occurs at a higher rate than for the general population as well.

Cormorbidity information is not given for delusional disorder or schizophreniform disorder.

Key Takeaways

You should have learned the following in this section:

- Schizophrenia has a high comorbidity with substance abuse disorders, anxiety-related disorders, OCD, and some medical conditions.

- Schizoaffective disorder is comorbid with substance use disorders, anxiety disorder, and metabolic syndrome.

Section 12.3 Review Questions

- What comorbidities exist between schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders?

12.4. Etiology

Section Learning Objectives

- Describe the biological causes of schizophrenia spectrum disorders.

- Describe the psychological causes of schizophrenia spectrum disorders.

- Describe the sociocultural causes of schizophrenia spectrum disorders.

12.4.1. Biological

12.4.1.1. Genetic/Family studies. Twin and family studies consistently support the biological theory. More specifically, if one identical twin develops schizophrenia, there is a 48% chance that the other will also develop the disorder within their lifetime (Coon & Mitter, 2007). This percentage drops to 17% in fraternal twins. Similarly, family studies have also found similarities in brain abnormalities among individuals with schizophrenia and their relatives; the more similarities, the higher the likelihood that the family member also developed schizophrenia (Scognamiglio & Houenou, 2014).

12.4.1.2. Neurobiological. There is consistent and reliable evidence of a neurobiological component in the transmission of schizophrenia. More specifically, neuroimaging studies have found a significant reduction in overall and specific brain region volumes, as well as tissue density of individuals with schizophrenia compared to healthy controls (Brugger, & Howes, 2017). Additionally, there has been evidence of ventricle enlargement as well as volume reductions in the medial temporal lobe. As you may recall, structures such as the amygdala (involved in emotion regulation), the hippocampus (involved in memory), as well as the neocortical surface of the temporal lobes (processing of auditory information) are all structures within the medial temporal lobe (Kurtz, 2015). Additional studies also indicate a reduction in the orbitofrontal regions of the brain, a part of the frontal lobe that is responsible for response inhibition (Kurtz, 2015).

12.4.1.3. Stress cascade. The stress-vulnerability model suggests that individuals have a genetic or biological predisposition to develop the disorder; however, symptoms will not present unless there is a stressful precipitating factor that elicits the onset of the disorder. Researchers have identified the HPA axis and its consequential neurological effects as the likely responsible neurobiological component responsible for this stress cascade.

The HPA axis is one of the main neurobiological structures that mediate stress. It involves the regulation of three chemical messengers (corticotropin-releasing hormone [CRH], adrenocorticotropic hormone [ACTH], and glucocorticoids) as they respond to a stressful situation (Corcoran et al., 2003). Glucocorticoids, more commonly referred to as cortisol, is the final neurotransmitter released which is responsible for the physiological change that accompanies stress to prepare the body to “fight” or “flight.”

It is hypothesized that in combination with abnormal brain structures, persistently increased levels of glucocorticoids in brain structures may be the key to the onset of psychosis in prodromal patients (Corcoran et al., 2003). More specifically, stress exposure (and increased glucocorticoids) affects the neurotransmitter system and exacerbates psychotic symptoms due to changes in dopamine activity (Walker & Diforio, 1997). While research continues to explore the relationship between stress and onset of the disorder, evidence for the implication of stress and symptom relapse is strong. More specifically, schizophrenia patients experience more stressful life events leading up to a relapse of symptoms. Similarly, it is hypothesized that the worsening or exacerbation of symptoms is also a source of stress as they interfere with daily functioning (Walker & Diforio, 1997). This stress alone may be enough to initiate the onset of a relapse.

12.4.2. Psychological

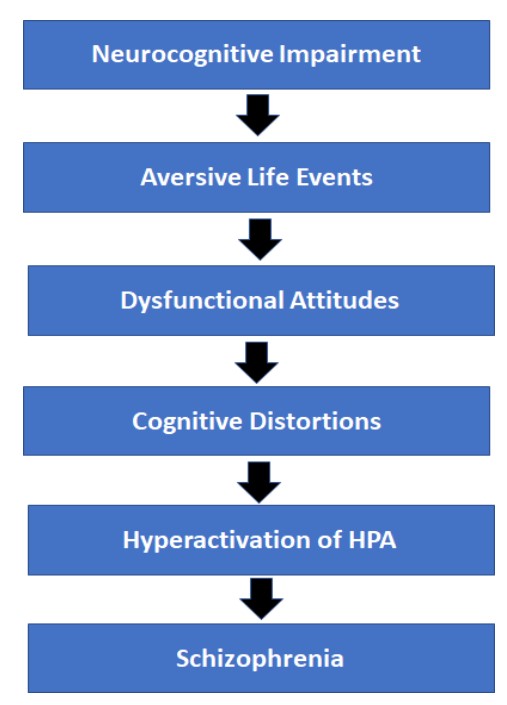

12.4.2.1. Cognitive. The cognitive model utilizes some of the aspects of the diathesis-stress model in that it proposes that premorbid neurocognitive impairment places individuals at risk for aversive work/academic/interpersonal experiences. These experiences, in turn, lead to dysfunctional beliefs and cognitive appraisals, ultimately leading to maladaptive behaviors such as delusions/hallucinations (Beck & Rector, 2005). Beck proposed the following diathesis-stress model for how schizophrenia develops (Fee Figure 12.1).

Figure 12.1. Diathesis-Stress Model of the Development of Schizophrenia

Adapted from Beck & Rector, 2005, pg. 580

Based on this theory, an underlying neurocognitive impairment (as discussed above) makes an individual more vulnerable to experience aversive life events such as homelessness, conflict within the family, etc. Individuals with schizophrenia are more likely to evaluate these aversive life events with a dysfunctional attitude and maladaptive cognitive distortions. The combination of the aversive events and negative interpretations produces a stress response in the individual, thus igniting hyperactivation of the HPA axis. According to Beck and Rector (2005), it is the culmination of these events leads to the development of schizophrenia.

12.4.3. Sociocultural

12.4.3.1. Expressed emotion. Research regarding supportive family environments suggests that families high in expressed emotion, meaning families that have high hostile, critical, or overinvolved family members, are predictors of relapse (Bebbington & Kuipers, 2011). In fact, individuals who return post-hospitalization to families with high criticism and emotional involvement are twice as likely to relapse compared to those who return to families with low expressed emotion (Corcoran et al., 2003). Several meta-analyses have concluded that family atmosphere is causally related to relapse in patients with schizophrenia, and that these outcomes can be improved when the family environment is improved (Bebbington & Kuipers, 2011). Therefore, one major treatment goal in families of patients with schizophrenia is to reduce expressed emotion within family interactions.

12.4.3.2. Family dysfunction. Even for families with low levels of expressed emotion, there is often an increase in family stress due to the secondary effects of schizophrenia. Having a family member with schizophrenia increases the likelihood of a disruptive family environment due to managing the patient’s symptoms and ensuring their safety while they are home (Friedrich et al., 2015). Because of the severity of symptoms, families with a loved one diagnosed with schizophrenia often report more conflict in the home as well as more difficulty communicating with one another (Kurtz, 2015).

Key Takeaways

You should have learned the following in this section:

- Biological causes of schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders include genetics, several brain structures, and the HPA axis.

- Psychological causes of schizophrenia spectrum disorders include the diathesis-stress model.

- Sociocultural causes of schizophrenia spectrum disorders include families high in expressed emotion and family dysfunction.

Section 12.4 Review Questions

- What evidence is there to support a biological model with respect to explaining the development and maintenance of the schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders?

- Discuss the stress-vulnerability model with respect to schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders.

- How does the sociocultural model explain the maintenance (and relapse) of schizophrenia related symptoms?

12.5. Treatment

Section Learning Objectives

- Describe psychopharmacological treatment options for schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders.

- Describe psychological treatment options for schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders.

- Describe family interventions for schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders.

While a combination of psychopharmacological, psychological, and family interventions is the most effective treatment in managing schizophrenia symptoms, rarely do these treatments restore a patient to premorbid levels of functioning (Kurtz, 2015; Penn et al., 2004). Although more recent advancements in treatment for schizophrenia appear promising, the disease itself is still viewed as one that requires lifelong treatment and care.

12.5.1. Psychopharmacological

Among the first antipsychotic medications used for the treatment of schizophrenia was Thorazine. Developed as a derivative of antihistamines, Thorazine was the first line of treatment that produced a calming effect on even the most severely agitated patients and allowed for the organization of thoughts. Despite their effectiveness in managing psychotic symptoms, conventional antipsychotics (such as Thorazine and Chlorpromazine) also produced significant side effects similar to that of neurological disorders. Therefore, psychotic symptoms were replaced with muscle tremors, involuntary movements, and muscle rigidity. Additionally, these conventional antipsychotics also produced tardive dyskinesia in patients, which included involuntary movements isolated to the tongue, mouth, and face (Tenback et al., 2006). While only 10% of patients reported the development of tardive dyskinesia, this percentage increased the longer patients were on the medication, as well as the higher the dose (Achalia, Chaturvedi, Desai, Rao, & Prakash, 2014). In efforts to avoid these symptoms, clinicians have been cognizant of not exceeding the clinically effective dose of conventional antipsychotic medications. If the management of psychotic symptoms cannot be resolved at this level, alternative medications are often added to produce a synergistic effect (Roh et al., 2014).

Due to the harsh side effects of conventional antipsychotic drugs, newer, arguably more effective second-generation or atypical antipsychotic drugs have been developed. The atypical antipsychotic drugs appear to act on both dopamine and serotonin receptors, as opposed to only dopamine receptors in the conventional antipsychotics. Because of this, common medications such as clozapine (Clozaril), risperidone (Risperdal), and aripiprazole (Abilify), appear to be more effective in managing both positive and negative symptoms. While there continues to be a risk of developing side effects such as tardive dyskinesia, recent studies suggest it is much lower than that of the conventional antipsychotics (Leucht, Heres, Kissling, & Davis, 2011). Thus, due to their effectiveness and minimal side effects, atypical antipsychotic medications are typically the first line of treatment for schizophrenia (Barnes & Marder, 2011).

It should be noted that because of the harsh side effects of antipsychotic medications in general, many individuals, nearly one half to three-quarters of patients, discontinue the use of antipsychotic drugs (Leucht, Heres, Kissling, & Davis, 2011). Because of this, it is also important to incorporate psychological interventions along with psychopharmacological treatment to both address medication adherence, as well as provide additional support for symptom management.

12.5.2. Psychological Interventions

12.5.2.1. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT). As discussed in previous chapters, the goal of treatment is to identify the negative biases and attributions that influence an individual’s interpretations of events and the subsequent consequences of these thoughts and behaviors. For schizophrenia, CBT focuses on the maladaptive emotional and behavioral responses to psychotic experiences, which is directly related to distress and disability. Therefore, the goal of CBT is not on symptom reduction, but rather to improve the interpretations and understandings of these symptoms (and experiences) which will reduce associated distress (Kurtz, 2015). Common features of CBT for schizophrenia patients include psychoeducation about their disease and the course of their symptoms (i.e., ways to identify coming and going of delusions/hallucinations), challenging and replacing the negative thoughts/behaviors associated with their delusions/hallucinations to more positive thoughts/behaviors, and finally, learning positive coping strategies to deal with their unpleasant symptoms (Veiga-Martinez, Perez-Alvarez, & Garcia-Montes, 2008).

Findings from studies exploring CBT as a supportive treatment have been promising. One study conducted by Aaron Beck (the founder of CBT) and colleagues (Grant, Huh, Perivoliotis, Stolar, & Beck, 2011) found that recovery-oriented CBT produced a marked improvement in overall functioning as well as symptom reduction in patients diagnosed with schizophrenia. This study suggests that by focusing on targeted goals such as independent living, securing employment, and improving social relationships, patients were able to slowly move closer to these targeted goals. By also including a variety of CBT strategies such as role-playing, scheduling community outings, and addressing negative cognitions, individuals were also able to address cognitive and social skill deficits.

12.5.3. Family Interventions

The diathesis-stress model of schizophrenia has primarily influenced family interventions. As previously discussed, the emergence of the disorder and exacerbation of symptoms is likely related to environmental stressors and psychological factors. While the degree in which environmental stress stimulates an exacerbation of symptoms varies among individuals, there is significant evidence to conclude that stress does impact illness presentation (Haddock & Spaulding, 2011). Therefore, the overall goal of family interventions is to reduce the stress on the individual that is likely to elicit the onset of symptoms.

Unlike many other psychological interventions, there is not a specific outline for family-based interventions related to schizophrenia. However, the majority of programs include the following components: psychoeducation, problem-solving skills, and cognitive-behavioral therapy.

Psychoeducation is important for both the patient and family members as it is reported that more than half of those recovering from a psychotic episode reside with their family (Haddock & Spaulding, 2011). Therefore, educating families on the course of the illness, as well as ways to recognize onset of psychotic symptoms, is important to ensure optimal recovery.

Problem-solving is a crucial component in the family intervention model. Seeing as family conflict can increase stress within the home, which in return can lead to worsening of psychotic symptoms, family members benefit from learning effective methods of problem-solving to address family conflicts. Additionally, teaching positive coping strategies for dealing with the symptoms of mental illness and its direct effect on the family environment may also alleviate some friction within the home

The third component, CBT, is similar to that described above. The goal of family-based CBT is to reduce negativity among family member interactions, as well as help family members adjust to living with someone with psychotic symptoms. These three components within the family intervention program have been shown to reduce re-hospitalization rates, as well as slow the worsening of schizophrenia-related symptoms (Pitschel-Walz, Leucht, Baumi, Kissling, & Engel, 2001).

12.5.3.1. Social skills training. Given the poor interpersonal functioning among individuals with schizophrenia, social skills training is another type of treatment commonly suggested to improve psychosocial functioning. Research has indicated that poor interpersonal skills not only predate the onset of the disorder but also remain significant even with the management of symptoms via antipsychotic medications. Impaired ability to interact with individuals in a social, occupational, or recreational setting is related to poorer psychological adjustment (Bellack, Morrison, Wixted, & Mueser, 1990). This can lead to greater isolation and reduced social support among individuals with schizophrenia. As previously discussed, social support has been identified as a protective factor of symptom exacerbation, as it buffers psychosocial stressors that are often responsible for the exacerbation of symptoms. Learning how to interact with others appropriately (e.g., establish eye contact, engage in reciprocal conversations, etc.) through role-play in a group therapy setting is one effective way to teach positive social skills.

12.5.3.2. Inpatient Hospitalizations. More commonly viewed as community-based treatments, inpatient hospitalization programs are essential in stabilizing patients in psychotic episodes. Generally speaking, patients will be treated on an outpatient basis; however, there are times when their symptoms exceed the needs of an outpatient service. Short-term hospitalizations are used to modify antipsychotic medications and implement additional psychological treatments so that a patient can safely return to their home. These hospitalizations generally last for a few weeks as opposed to a long-term treatment option that would last months or years (Craig & Power, 2010).

In addition to short-term hospitalizations, there are also partial hospitalizations where an individual enrolls in a full-day program but returns home for the evening. These programs provide individuals with intensive therapy, organized activities, and group therapy programs that enhance social skills training. Research supports the use of partial hospitalizations as individuals enrolled in these programs tend to do better than those who enter outpatient care (Bales et al., 2014).

Key Takeaways

You should have learned the following in this section:

- Psychopharmacological treatment options for schizophrenia spectrum disorders include antipsychotic drugs such as Thorazine, Chlorpromazine, Clozaril, Risperdal, and Abilify.

- Psychological treatment options for schizophrenia spectrum disorders include CBT, the goal of which is to improve the interpretations and understandings of symptoms (and experiences) which will reduce associated distress.

- Family interventions for schizophrenia spectrum disorders include psychoeducation, problem-solving skills, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), social skills training, and inpatient/partial hospitalizations.

Section 12.5 Review Questions

- Define tardive dyskinesia.

- What pharmacological interventions have been effective in managing schizophrenia related disorder symptoms?

- What is the main goal of family interventions? How is this achieved?

Module Recap

In our first module of Part V – Block 4, we discussed the schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders to include schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, schizoaffective disorder, and delusional disorder. We started by describing their common features, such as delusions, hallucinations, disorganized thinking, disorganized/abnormal motor behavior, and negative symptoms. This led to a discussion of the epidemiology, comorbidity, etiology, and treatment options for the disorders.

3rd edition