Module 6: Operant Conditioning

Module Overview

With respondent conditioning covered and applications discussed, we now begin the very tall order of describing Skinner’s operant conditioning which was based on the work of Edward Thorndike. The four behavioral contingencies, factors on operant learning, reinforcement schedules, theories related to reinforcement, stimulus control, avoidance, punishment, and extinction will all be covered. Take your time working through this module and be sure to ask your instructor if you have any questions.

Module Outline

- 6.1. Historical Background

- 6.2. Basics of Operant Conditioning

- 6.3. Factors on Operant Learning

- 6.4. Schedules of Reinforcement

- 6.5. Theories of Reinforcement

- 6.6. Stimulus Control

- 6.7. Aversive Control – Avoidance and Punishment

- 6.8. Extinction

Module Learning Outcomes

- Outline historical influences/key figures on the development of operant conditioning.

- Clarify what happens when we make a behavior and outline the four contingencies.

- Outline key factors in operant learning.

- Clarify how reinforcement can occur continuously or partially.

- Describe the various partial schedules of reinforcement.

- Compare theories of reinforcement.

- Describe what stimulus control is and the different ways to gain it.

- Clarify why avoidance is important to learning.

- Describe punishment procedures.

- Describe what extinction and spontaneous recovery are.

6.1. Historical Background

Section Learning Objectives

- Describe the work of Thorndike.

- Describe Skinner’s work leading to the development of operant conditioning.

6.1.1. The Work of Thorndike

Influential on the development of Skinner’s operant conditioning, Edward Lee Thorndike (1874-1949) proposed the law of effect (Thorndike, 1905) which says if our behavior produces a favorable consequence, in the future when the same stimulus is present, we will be more likely to make the response again because we expect the same favorable consequence. Likewise, if our action leads to dissatisfaction, then we will not repeat the same behavior in the future.

He developed the law of effect thanks to his work with the Puzzle Box. Cats were food deprived the night before the experimental procedure was to occur. The next morning, they were placed in the puzzle box and a small amount of food was positioned outside the box close enough to be smelled, but the cat could not reach the food. To get out, the cat could manipulate switches, buttons, levers, or step on a treadle. Only the treadle would open the gate though, allowing the cat to escape the box and eat some of the food. But just some. The cat was then placed back in the box to figure out how to get out again, the food being its reward for doing so. With each subsequent escape and re-insertion into the box, the cat became faster until he/she knew exactly what had to be done to escape. This is called trial and error learning or making responses randomly until the solution is found. Think about it as trying things out to see what works, or what does not (making a mistake or error) and then by doing this enough times you figure out the solution to the problem, as the cat did. The process of learning in this case is gradual, not sudden. The response of stepping on the treadle produces a favorable consequence of escaping the box meaning that the cat will step on the treadle in the future if it produces the same consequence. Behaviors that produce favorable consequences are “stamped in” while those producing unfavorable consequences are “stamped out,” according to Thorndike.

Thorndike also said that stimulus and responses were connected by the organism and this lead to learning. This approach to learning was called connectionism and is similar to Locke’s idea of associationism. We more so use the latter term today as we talk about associative learning.

6.1.2. The Work of Skinner

B.F. Skinner (1904-1990) chose to study behavior through the use of what he called a Skinner box. Versions were created for rats and pigeons. In the case of the former, rats earned food pellets when they pressed a lever or bar and for the latter, pigeons earned food reinforcers when they pecked a response key. The Skinner box was known as a “free operant” procedure because the animal could decide when to make the desired response to earn a food pellet (or access to the food) and is not required to respond at a pre-established time. Consider that in maze learning the experimenter initiates a trial by placing a rat in the start box and opening the door for it to run the maze. Skinner’s development of such a procedure showed that the animal’s rate of response was governed by the conditions that he established as the experimenter and was in keeping with the strict standards of the scientific study of behavior established by Pavlov.

Skinner described two types of behaviors — respondent and operant. Respondent behaviors describe those that are involuntary and reflexive in nature. These are the types of behavior Pavlov described in his work and can be conditioned to occur in new situations (i.e. the NS and US relationship). In contrast, operant behaviors include any that are voluntary and controlled instead by their consequences. We will focus on operant behaviors for the duration of this module.

6.2. Basics of Operant Conditioning

Section Learning Objectives

- Clarify what happens when we make a behavior (the framework).

- Define operant conditioning.

- Clarify what operant behaviors are.

- Define contingency.

- Contrast reinforcement and punishment.

- Clarify what positive and negative mean.

- Outline the four contingencies of behavior.

- Distinguish primary and secondary reinforcers.

- Define generalized reinforcer.

- Define discriminative stimuli.

6.2.1. What is Operant Conditioning?

Before jumping into a lot of terminology, it is important to understand what operant conditioning is or attempts to do. But before we get there, let’s take a step back. So what happens when we make a behavior? Consider this framework:

Stimulus, also called an antecedent, is whatever comes before the behavior, usually from the environment. Response is a behavior. And of course, consequence is the result of the behavior that makes a behavior more or less likely to occur in the future. Presenting this framework is important because operant conditioning as a learning model focuses on the person making some response for which there is a consequence. As we learned from Thorndike’s work, if the consequence is favorable or satisfying, we will be more likely to make the response again (when the stimulus occurs). If not favorable or unsatisfying, we will be less likely. Recall that respondent or classical conditioning, which developed thanks to Pavlov’s efforts, focuses on stimulus and response, and in particular, the linking of two types of stimuli – NS and US.

Before moving on let’s state a formal definition for operant conditioning:

Operant conditioning is a type of associative learning that focuses on consequences that follow a response that we make and whether it makes a behavior more or less likely to occur in the future.

Return to our discussion of operant behaviors from Section 6.1.2. Operant behaviors are voluntary and controlled by their consequences. Let’s say a child chooses to study and does well on an exam. His parents celebrate the grade by taking him out for ice cream (the positive outcome of the behavior of studying). In the future, he studies harder to get the ice cream. But what if his brother decides to talk back to his parents and is scolded for doing so. He might lose television privileges. In the future, the brother will be less likely to talk back and stay quiet to avoid punishment. In both cases, the behavior was freely chosen and the likelihood of making that behavior in the future was linked to the consequence in the present. These operant behaviors are sometimes referred to as operants.

Operant behaviors are emitted by the organism such as in the case of the child studying or the child talking back. In contrast, respondent behaviors are elicited by stimuli (either the US or CS) such as a dog salivating to either the sight of food (US) or the sound of a bell (CS/NS). Also, operant behaviors can be thought of as a class of responses, all of which are capable of producing a consequence. For instance, studying is a general behavior, but it could include spaced study sessions such as spending 30 minutes after each class going over what was covered that day or massed studying the night before the exam. Both are studying behavior and it is easier to predict their occurrence than an exact type of behavior. In the case of talking back, consider that a child could just make a snide comment at the parent or engage in argumentative behavior. The result is the same (negative consequence) for engaging in this behavior, whatever form it may take exactly (the topography of the behavior).

6.2.2. Behavioral Contingencies

As we have seen, the basis of operant conditioning is that you make a response for which there is a consequence. Based on the consequence you are more or less likely to make the response again. Recall that a contingency is when one thing occurs due to another. Think of it as an If-Then statement. If I do X, then Y will happen. For operant conditioning, this means that if I make a behavior, then a specific consequence will follow. The events (response and consequence) are linked in time (more on this in a bit).

What form do these consequences take? There are two main ways they can present themselves.

- Reinforcement — Due to the consequences, a behavior/response is more likely to occur in the future. It is strengthened.

- Punishment — Due to the consequence, a behavior/response is less likely to occur in the future. It is weakened.

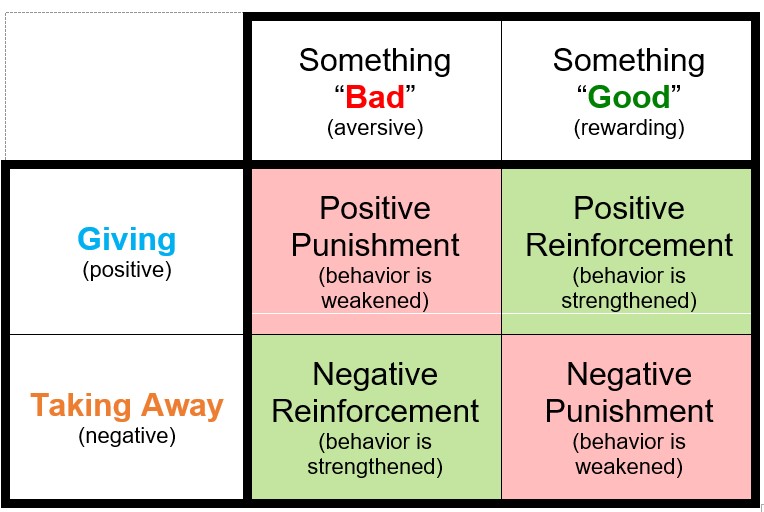

Reinforcement and punishment can occur as two types — positive and negative. These words have no affective connotation to them meaning they do not imply good or bad, or an emotional state. Positive means that you are giving something — good or bad. Negative means that something is being taken away — good or bad. Check out Table 6.1 below for how these contingencies are arranged. Bear in mind that the actual contingency presented in the cells needs to be inferred from what is along the outside. We know giving is positive and if you are giving some bad or aversive thing, you should be trying to weaken a behavior, which is punishment. Hence, giving something bad that would weaken a behavior is positive punishment. The others work the same. This is one way to teach this concept. If you learned another way and understand the four contingencies, stick with what you learned.

Table 6.1. Contingencies in Operant Conditioning

Let’s go through each:

- Positive Punishment (PP) — If something bad or aversive is given or added, then the behavior is less likely to occur in the future. If you talk back to your mother and she slaps your mouth, this is a PP. Your response of talking back led to the consequence of the aversive slap being delivered or given to your face.

- Positive Reinforcement (PR) — If something good is given or added, then the behavior is more likely to occur in the future. If you study hard and earn, or are given, an A on your exam, you will be more likely to study hard in the future. Your parents may also give you money for your efforts. Hence the result of studying could yield two PRs — the ‘A’ and the money.

- Negative Reinforcement (NR) — This is a tough one for students to comprehend because the terms do not seem to go together and are counterintuitive. But it is really simple and you experience NR all the time. This is when something bad or aversive is taken away or subtracted due to your actions, making you more likely to do the same behavior in the future when some stimulus presents itself. For instance, what do you do if you have a headache? You likely answered take Tylenol. If you do this and the headache goes away, you will take Tylenol in the future when you have a headache. NR can either result in current escape behavior or future avoidance behavior. What does this mean? Escape behavior occurs when we are presently experiencing an aversive event and want it to end. We make a behavior and if the aversive event, such as withdrawal symptoms from not drinking coffee for a while, goes away, then we can say we escaped the aversive state. Feeling hungry and eating food is another example. Taking Tylenol helps us to escape a headache. In fact, to prevent the symptoms from ever occurring, we might drink coffee at regular intervals throughout the day. This is called avoidance behavior. By doing so we have removed the possibility of the aversive event occurring and this behavior demonstrates that learning has occurred. We might also eat small meals throughout the day to avoid the aversive state of being hungry.

- Negative Punishment (NP) — This is when something good is taken away or subtracted making a behavior less likely in the future. If you are late to class and your professor deducts 5 points from your final grade (the points are something good and the loss is negative), you will hopefully be on time in all subsequent classes.

To easily identify contingencies, use the following three steps:

- Identify if the contingency is positive or negative. If positive, you should see words indicating something was given, earned, or received. If negative, you should see words indicating something was taken away or removed.

- Identify if a behavior is being reinforced or punished. If reinforced, you will see a clear indication that the behavior increases in the future. If punished, there will be an indication that the behavior decreases in the future.

- The last step is easy. Just put it all together. Indicate first if it is P or N, and then indicate if there is R or P. So you will have either PR, PP, NR, or NP. Check above for what these acronyms mean if you are confused.

Example:

You study hard for your calculus exam and earn an A. Your parents send you $100. In the future, you study harder hoping to receive another gift for an exemplary grade.

- P or N — “Your parents send you $100” but also “earn an A” — You are given an A and money so you have two reinforcers that are given which is P

- R or P — “In the future you study harder….” — behavior increases so R

- Together — PR

To make your life easier, feel free to underline where you see P or N and R or P. You cannot go wrong if you do.

6.2.3. Primary vs. Secondary (Conditioned)

The type of reinforcer or punisher we use is important. Some are naturally occurring while some need to be learned. We describe these as primary and secondary reinforcers and punishers. Primary refers to reinforcers and punishers that have their effect without having to be learned or are unconditioned. Food, water, temperature, and sex, for instance, are primary reinforcers while extreme cold or hot or a punch on the arm are inherently punishing. A story will illustrate the latter. When I was about 8 years old, I would walk up the street in my neighborhood saying, “I’m Chicken Little and you can’t hurt me.” Most ignored me but some gave me the attention I was seeking, a positive reinforcer. So, I kept doing it and doing it until one day, another kid was tired of hearing about my other identity and punched me in the face. The pain was enough that I never walked up and down the street echoing my identity crisis for all to hear. Pain was a positive punisher and did not have to be learned. That was definitely not one of my finer moments in life.

Secondary or conditioned reinforcers and punishers are not inherently reinforcing or punishing but must be learned. An example was the attention I received for saying I was Chicken Little. Over time I learned that attention was good. Other examples of secondary reinforcers include praise, a smile, getting money for working or earning good grades, stickers on a board, points, getting to go out dancing, and getting out of an exam if you are doing well in a class. Examples of secondary punishers include a ticket for speeding, losing television or video game privileges, being ridiculed, or a fee for paying your rent or credit card bill late. Really, the sky is the limit, especially with reinforcers.

A particular type of secondary reinforcer is called a generalized reinforcer (Skinner, 1953) and obtains the name because of being paired with many other reinforcers. Consider the example of money. With it, we can purchase almost anything. Maybe we should even add credit or debit cards to this discussion since most of us carry them and not actual money nowadays. In Module 7 we will discuss applications of operant conditioning, one of which is behavior modification. In the token economy, generalized reinforcers are used in the form of tokens and are used to purchase items called backup reinforcers. More on this later.

6.2.4. Discriminative Stimuli

Sometimes a behavior is reinforced in the presence of a specific stimulus and not reinforced when the stimulus or antecedent is not present. These stimuli signal when reinforcement will occur, or not, and are called discriminative stimuli (also called an SD). Recall our earlier discussion of the S à R à C model or Stimulus-Response-Consequence. Though our focus was on R and C, discriminative stimuli show that S can be important too. Consider the rat in the Skinner box. Lever pushes earn food reinforcers, but what if this is true only if a light above the lever is on? In this case, the light serves as a discriminative stimulus and signals that reinforcement is possible. If the light is not on, reinforcement does not occur no matter how many times the lever is pushed (or how hard).

As a stimulus can signal reinforcement, so too it can signify punishment. At times my dog sprays the trashcan in an effort to mark his territory. When he does this he receives either a soft smack across the rear end or is verbally scolded. But if I see him approaching the trashcan, I can hold up my hand which usually signifies the punishment he will endure if he sprays the trashcan. The sight of my hand (or a newspaper rolled up) signals punishment if a behavior is engaged in.

Before moving on, pause and reflect on what you have learned. It may even be a good idea to take a break for a period of time. Reward your progress so far with a television or game break. But don’t take too long. You do have a lot more to cover.

6.3. Factors on Operant Learning

Section Learning Objectives

- Clarify why the concept of contingency is important to operant learning.

- Define contiguity.

- Clarify whether a reinforcer should be delivered immediately or delayed.

- Explain why the magnitude of a reinforcer is important.

- Define motivating operations and describe the two types.

- Contrast intrinsic and extrinsic reinforcement.

- Clarify the importance of individual differences.

- Contrast natural and contrived reinforcers.

6.3.1. Contingency, Again

One key issue related to reinforcers and punishers is contingency. The reinforcer or punisher should be unique to the situation. So, if you do well on your report card, and your parents give you $25 for each A, and you only get money for school performance, the secondary reinforcer of money will have an even greater effect. This ties back to our discussion of contingency, or those If-Then statements related to behavior. It would be presented as such: If I earn all As in school, then my parents will give me $25 per A and only for engaging in this behavior. In other words, I will not earn the money if I join a club or other student group on campus as an extracurricular activity.

6.3.2. Contiguity

Contiguity refers to the time between when the behavior is made and when its consequence occurs. Do you think learning is better if this period is short or long? Research has shown that shorter intervals produce faster learning (Okouchi, 2009). If the time between response and consequence is too long, another behavior could occur that is reinforced instead of the target behavior.

6.3.3. Immediate vs. Delayed

It should not be surprising to know that the quicker you deliver a reinforcer or punisher after a response, the more effective it will be. This is called immediacy. Don’t be confused by the word. If you notice, you can see immediately in it. If a person is speeding and you ticket them right away, they will stop speeding. If your daughter does well on her spelling quiz, and you take her out for ice cream after school, she will want to do better. Delayed reinforcement or punishment has a relatively weak effect on behavior. Think about the education you are pursuing right now. The reinforcer is the degree you will earn, but it will not be conferred for at least four years from the time you start. That is a long way off and you can engage in behaviors now that produce immediate reinforcement such as hanging out with friends, watching television, playing video games, or taking a nap. So, what do you do to stay focused and keep your eye on the prize (the delayed reinforcement of the degree)? More on this in Module 7.

6.3.4. Magnitude of a Reinforcer or Punisher

Are you more likely to work hard for $25 an A or $5 an A? The answer is likely $25 an A. Premeditated homicide or murder is another example. If the penalty is life in prison and possibly the death penalty, this will have a greater effect on deterring the heinous crime than just giving 10 years in prison with the chance of parole. This factor on operant learning is called magnitude, or how large a reinforcer or punisher is, and it has a definite effect on behavior.

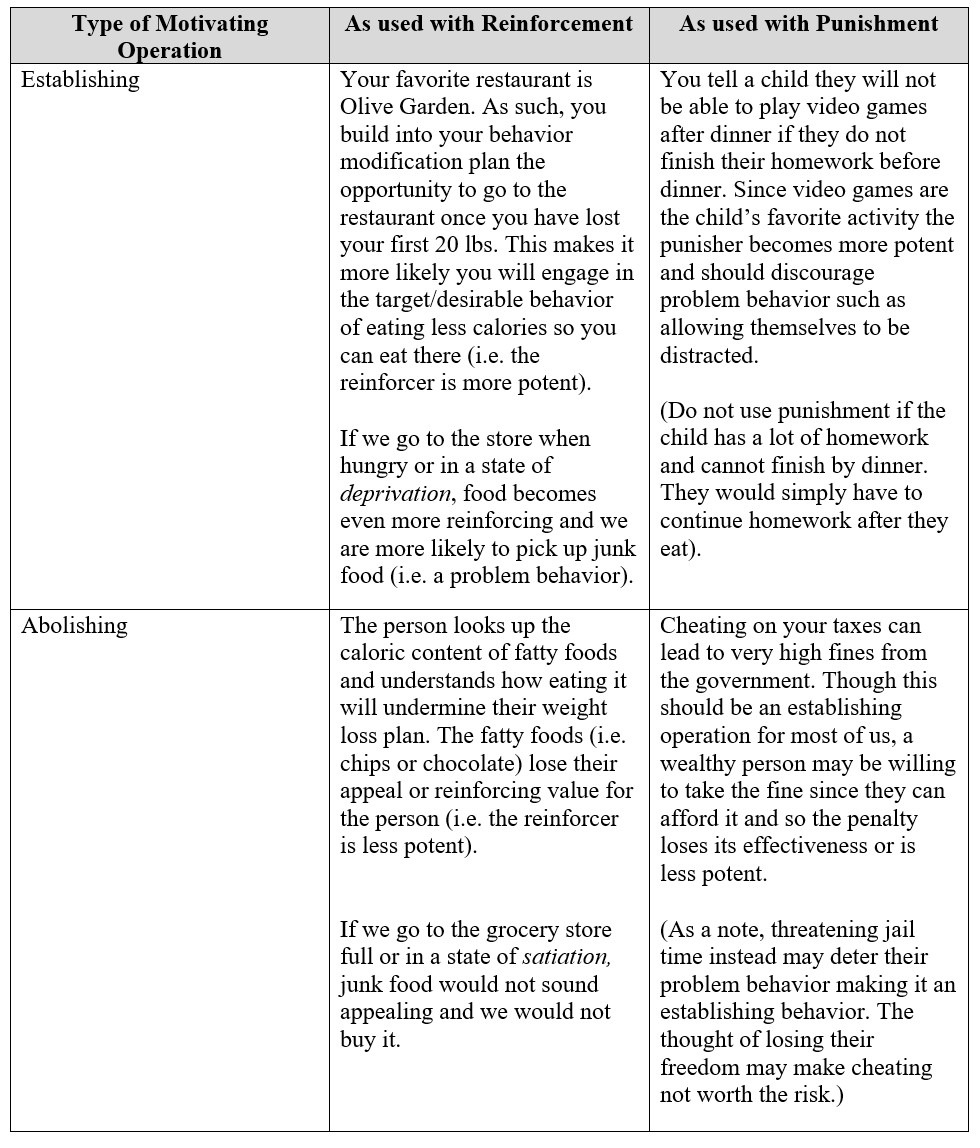

6.3.5. Motivating Operations

At times, events make a reinforcer or punisher more or less reinforcing or punishing. We call these motivating operations, and they can take the form of an establishing or an abolishing operation. First, an establishing operation is when an event makes a reinforcer or punisher more potent. Reinforcers become more reinforcing (i.e. behavior is more likely to occur) and punishers more punishing (i.e. behavior is less likely to occur). Second, an abolishing operation is when an event makes a reinforcer or punisher less potent. Reinforcers become less reinforcing (i.e. behavior is less likely to occur) and punishers less punishing (i.e. behavior is more likely to occur). See Table 6.2 below for examples of establishing and abolishing operations.

Table 6.2. Examples of Establishing and Abolishing Operations

6.3.6. Intrinsic vs. Extrinsic

For some of us, we obtain enjoyment, or reinforcement, from the mere act of engaging in a behavior, called intrinsic reinforcement. For instance, I love teaching, and apparently writing books. The act of writing or teaching is rewarding by enhancing my self-esteem, making me feel like I am making a difference in the lives of my students, and helping me to feel accomplished as a human being. Despite this, I also receive a paycheck for teaching (and side pay for writing the books — OER) which is admittedly important too as I have bills to pay. This is called extrinsic reinforcement and represents the fact that some sources of reinforcement come from outside us or are external.

Before moving on, consider the question of whether receiving an extrinsic reinforcer when you are already deriving intrinsic reinforcement from a behavior can reduce your overall intrinsic reinforcement. Consider college baseball or football players who play for the love of the game (intrinsic reinforcement). What happens if they go pro and are making millions of dollars suddenly and being showered with praise and attention from fans and the media (extrinsic reinforcement)? To answer the question, do a quick literature search using intrinsic reinforcement and external rewards as keywords, or related words. What do you come up with?

6.3.7. Individual Differences

The example of the video games demonstrates establishing and abolishing operations, but it also shows one very important fact — all people are different. Reinforcers will motivate behavior. That is a universal occurrence and unquestionable. But the same reinforcers will not reinforce all people. This shows diversity and individual differences.

6.3.8. Natural vs. Contrived Reinforcers

Reinforcers can be classified as to whether they occur naturally in our environment, or whether they are arranged to modify a behavior or are considered artificial. The former are called natural reinforcers while the latter are called contrived reinforcers. An example should clarify any confusion you might have. Let’s say you want to help a roommate who is incredibly shy learn to talk to other people. You might set up a system whereby for every new person he talks to, he receives a reinforcer such as getting out of doing the dishes that night. Specifically, this is a negative reinforcer because it is taking away something aversive, which is dish duty, and is contrived since it is arranged by his roommate. Continency is also present as there is a condition on receiving the reinforcer — if he talks to a new person, then he gets out of doing the dishes. Now consider that he actually takes a chance and talks to someone new. Let’s say he gathers the courage needed to talk to a girl he really likes. If the conversation goes well, he will come out of it feeling very good about himself, gain confidence, and if lucky, get a date with her or at least the chance to engage in conversation again in the future. This is not arranged by anyone but occurs naturally as a result of the positive interaction, and so is a natural reinforcer.

So which type of reinforcer — natural or contrived — do you think is more effective? Is getting out of dishes more effective to establish the behavior of talking to new people (and overcoming a potential social phobia) than feeling excited after a positive interaction? Not likely, and Skinner (1987) stated that natural reinforcers are stronger than contrived reinforcers.

6.4. Schedules of Reinforcement

Section Learning Objectives

- Contrast continuous and partial/intermittent reinforcement.

- List the four simple reinforcement schedules and exemplify each.

- Describe duration schedules.

- Describe noncontingent schedules.

- Describe progressive schedules.

- Outline the complex schedules.

- Define differential reinforcement.

- Outline the five forms differential reinforcement can take.

6.4.1. Continuous vs. Partial Reinforcement

In operant conditioning, the rule for determining when and how often we will reinforce a desired behavior is called the reinforcement schedule. Reinforcement can either occur continuously, meaning that every time the desired behavior is made the person or animal will receive a reinforcer, or intermittently/partially, meaning that reinforcement does not occur with every behavior. Our focus will be on partial/intermittent reinforcement. In terms of when continuous reinforcement might be useful, consider trying to train your cat to use the litter box (and not your carpet). Every time the cat uses the litter box you would want to give it a treat. This will be the trend early in training. Once the cat is using the litter box regularly you can switch to an intermittent schedule and eventually just faze out reinforcement. So how might an intermittent schedule look?

6.4.2. Simple Reinforcement Schedules

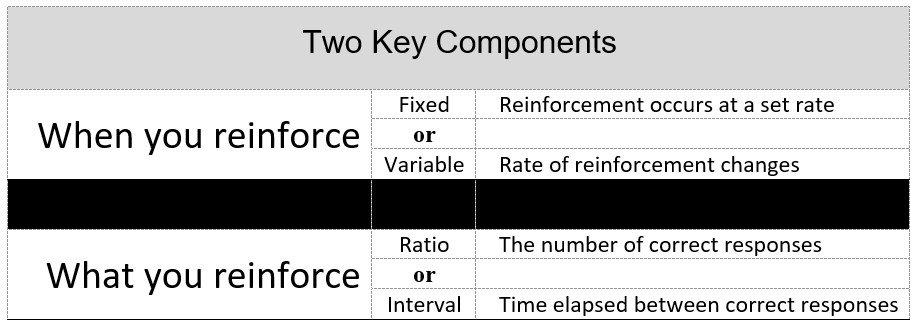

Figure 6.1. shows that that are two main components that make up a reinforcement schedule — when you will reinforce and what is being reinforced. In the case of when, it will be either fixed, or at a set rate, or variable, and at a rate that changes. In terms of what is being reinforced, we will either reinforce responses or the first response after a period of time.

Figure 6.1. Key Components of Reinforcement Schedules

These two components pair up as follows:

6.4.2.1. Fixed Ratio Schedule (FR). With this schedule, we reinforce some set number of responses. For instance, every twenty problems (fixed) a student gets correct (ratio), the teacher gives him an extra credit point. A specific behavior is being reinforced — getting problems correct. Note that if we reinforce each occurrence of the behavior, the definition of continuous reinforcement, we could also describe this as an FR1 schedule. The number indicates how many responses have to be made and, in this case, it is one.

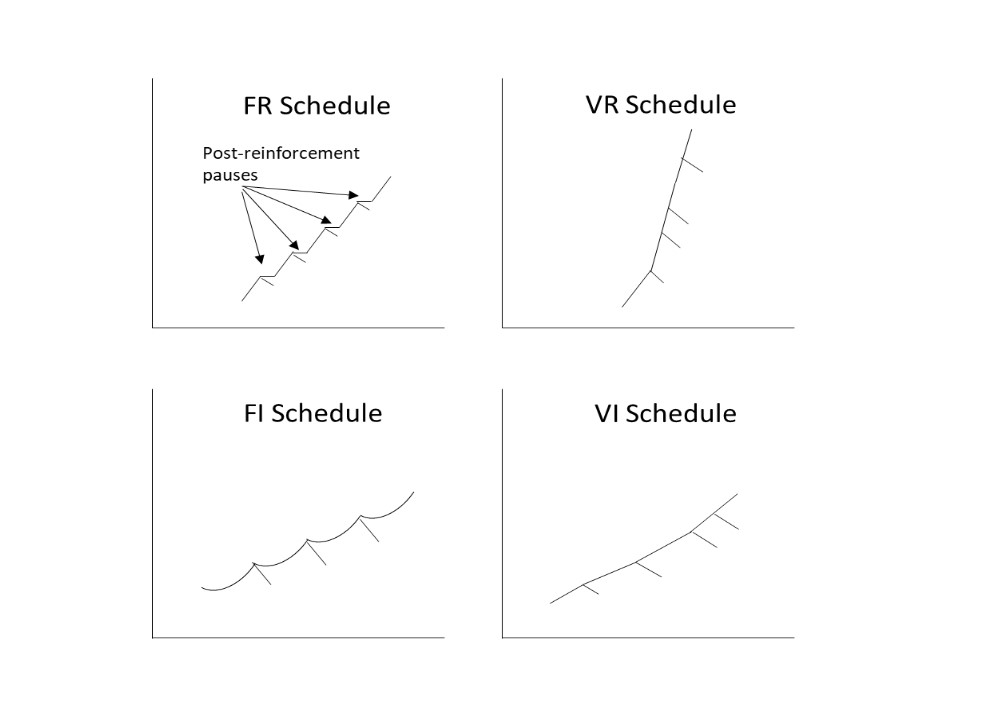

FR schedules are characterized by a high rate of performance with short pauses called post-reinforcement pauses. A rat, for instance, will press the lever quickly and until a food pellet drops, eat it, walk around the chamber for a bit, and then return to the business of lever pressing. The pause to walk around the chamber represents taking a break, and when rats (or people) are asked to make more behaviors the break is longer. In other words, the pause after making 50 lever presses (FR 50) will be longer than after making 20 lever presses (FR 20). See Figure 6.2 for the typical response pattern on an FR schedule.

6.4.2.2. Variable Ratio Schedule (VR). We might decide to reinforce some varying number of responses such as if the teacher gives the student an extra credit point after finishing an average of 5 problems correctly (VR 5). We might reinforce after 8 correct problems, then 5, then 3, and then 4 problems. The total number of correct problems across trials is 20. To obtain the average, divide by the number of trials which is 4 and this yields an average of 5 problems answered correctly. This is useful after the student is obviously learning the material and does not need regular reinforcement. Also, since the schedule changes, the student will keep responding in the absence of reinforcement.

VR schedules yield a high and steady rate of responding and typically produce fewer and shorter post-reinforcement pauses. Like an FR schedule, the payoff is the same. An animal on an FR 25 schedule will receive the same amount of food pellets as a different animal on a VR 25 schedule. See Figure 6.2 for the typical response pattern on a VR schedule.

6.4.2.3. Fixed Interval Schedule (FI). With an FI schedule, you will reinforce the first behavior made after some set amount of time. Let’s say a company wanted to hire someone to sell their products. To attract someone, they could offer to pay them $10 an hour 40 hours a week and give this money every two weeks. Crazy idea but it could work. ☺ Saying the person will be paid every indicates fixed, and two weeks is time or interval. So, FI. Rats in a Skinner box will be reinforced when they make the first lever press after 20 seconds of time has passed. Hence, the rat would be on a FI 20(sec) schedule and would not receive any food until another 20 seconds has passed (and then it pushed the lever).

FI schedules produce a response pattern best described as scalloped shape. At the beginning of the interval, responses are almost non-existent but as time passes the rate of responding increases, especially as the end of the interval nears. The FI schedule has a post-reinforcement pause, like the FR schedule. Consider your study habits for a minute. When a new unit starts, you are not likely to study. As the unit progresses, you may start to study your notes, and as the unit nears the end, your rate of studying will be very high as you know the exam will be soon. This process is repeated when the next unit starts. See Figure 6.2 for the typical response pattern on a FI schedule.

6.4.2.4. Variable Interval Schedule (VI). Finally, you could reinforce the first response after some changing amount of time. Maybe employees receive payment on Friday one week, then three weeks later on Monday, then two days later on Wednesday, then eight days later on Thursday. Etc. This could work, right? Maybe not for a normal 9-5 job, but it could if you are working for a temp agency. VI schedules reinforce the first response after a varying amount of time. Let’s say our rat in the FI schedule example was moved to a VI 20(sec) schedule. He would be reinforced for the next response after an average of 20 seconds. The actual intervals could be 30 seconds, 15 seconds, 25 seconds, and 10 seconds (30+15+25+10/4 = 20).

VI schedules produce almost no post-reinforcement pauses and a steady rate of responding that is predictable. For humans, waiting in line at the DMV is a great example of a VI schedule. Each person ahead of us that completes his or her business and leaves reinforces our waiting, but how long each person ahead of us takes when they make it to the counter will vary. We may be reinforced for our waiting after just 30 seconds with one customer but after several minutes with another customer. The amount of time we wait for each customer to have their problem solved produces an average amount of time after which we are reinforced for our response of waiting (and gradually sliding forward). See Figure 6.2 for the typical response pattern on a VI schedule.

Figure 6.2. Intermittent Schedules of Reinforcement Response Patterns

6.4.3. A Way to Easily Identify Reinforcement Schedules

To identify the reinforcement schedule, use the following three steps:

- When does reinforcement occur? Is it at a set or varying rate? If fixed (F), you will see words such as set, every, and each. If variable (V), you will see words like sometimes or varies.

- Next, determine what is reinforced — some number of responses or the first response after a time interval. If a response (R), you will see a clear indication of a behavior that is made. If interval (I), some indication of a specific or period of time will be given.

- Put them together. First, identify the rate. Write an F or V. Next identify the what and write an R or I. This will give you one of the pairings mentioned above — FI, FR, VI, or VR.

Example:

You girlfriend or boyfriend display affection about every three times you give him/her a compliment or flirt.

- F or V — “about every three times” which is V.

- R or I — “give him/her a compliment or flirt” which is a response or R.

- Together — VR

To make your life easier, feel free to underline where you see F or V and R or I. You cannot go wrong if you do, as with the contingencies exercise.

6.4.4. Other Types of Simple Schedules

Though the four simple schedules mentioned above are the most commonly investigated by researchers, several other simple schedules exist and do receive attention as well. We will now cover them.

6.4.4.1. Fixed and variable duration schedules. In a fixed duration (FD) schedule, the organism has to make the behavior continuously for a period of time after which a reinforcer is delivered. An example would be a child practicing shooting hoops for 60 minutes before he receives a reinforcer such as playing a video game (FD 60-min). In a variable duration (VD) schedule, the behavior must be made continuously for some varying amount of time. A coach may have his players running drills on the football field and provide the reinforcement of a refreshing drink at different times. This could occur after 5, 12, 7, and 16 minutes of practice but on average, the athletes will practice 10 minutes before they receive reinforcement (VD 10-min). Interestingly, as I write this module, I realized that I have done all of my textbook writing on an FD schedule. I generally sit down and write for a designated period of time each day. Once this time is complete, I provide myself reinforcement such as getting to go to the gym, reading my current science fiction novel, or taking a break to watch a movie. The reinforcement comes no matter how productive I am, and some days I am not as productive as others. I can write 20 pages in 2 hours when properly motivated but other days may just write 5 pages in the same period. Should I write according to an FR schedule though? Instead of writing for a fixed period of time (FD 120-min), I could decide to complete a certain number of sections in a module. For my current project, I may decide to write 2 sections in a module per day or a FR 2-sections schedule, before receiving one of the aforementioned reinforcers. How do you tackle studying or writing a large term paper? Do you use an FD or FR schedule and does it work for you?

6.4.4.2. Noncontingent schedules (FT/VT). Noncontingent Reinforcement Schedules involve delivering a reinforcer after an interval of time, regardless of whether the behavior is occurring or not. In this respect they are response-independent schedules which should make sense given the fact that they are noncontingent, meaning there is no If-then condition. In a fixed time (FT) schedule an organism receives reinforcement after a set amount of time such as a pigeon having access to food after 30 seconds (FT 30-sec) whether it is pecking a key or not. In an FI 30-sec schedule, the pigeon would have to peck the key after the 30-second interval was over to receive access to the food. FT schedules are useful in token economies as you will come to see in Module 7.

In a variable time (VT) schedule, reinforcement occurs after a varying amount of time has passed, regardless of whether the desired behavior is being made. In a VT 20-sec schedule, the rat receives a food pellet after an average of 20 seconds whether it is pushing the lever or not. This reinforcement could occur after 18, 34, 7, 53, etc. seconds with the average being 20 seconds.

6.4.4.3. Progressive schedules. In a progressive schedule, the rules determining what the contingencies are change systematically (Stewart, 1975). One such schedule is called a progressive ratio (PR) schedule (Hodos, 1961) and involves the requirement for reinforcement increasing in either an arithmetic or geometric way, and after each reinforcement has occurred. For instance, a rat may receive reinforcement after every 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 lever pushes (arithmetic) or after 6, 12, 24, 48, and 96 times. The reinforcer may even change such as the quality of the food declining with each reinforcement. Eventually, the rate of behavior will decrease sharply or completely stop, called the break point. Roane, Lerman, and Vorndran (2001) utilized a PR schedule to show that reinforcing stimuli may be differentially effective as response requirements increase. Stimuli associated with more responding as the schedule requirement increased were more effective in the treatment of destructive behaviors than those associated with less responding. The authors note, “practitioners should therefore consider arranging reinforcer presentation according to task difficulty based on the relation between reinforcer effectiveness and response requirements” (pg. 164).

6.4.5. Complex Schedules

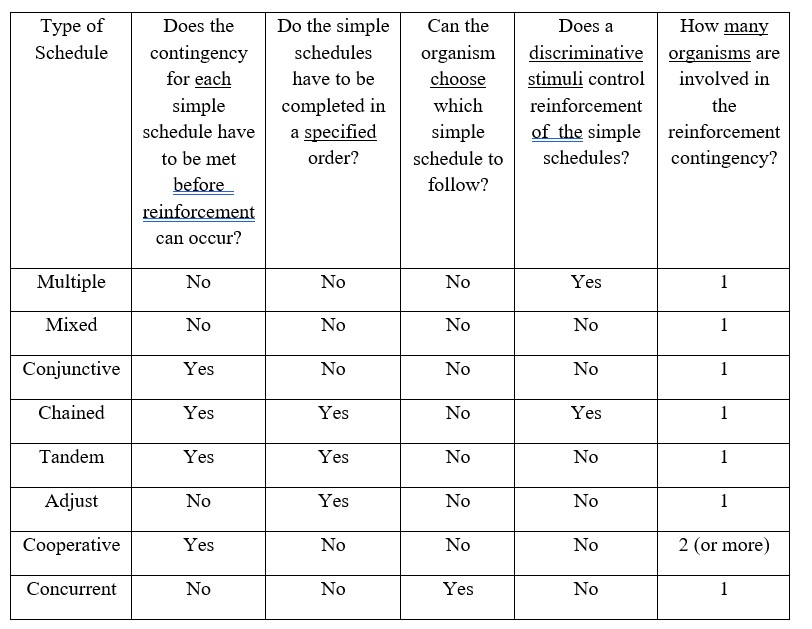

Unlike simple schedules that only have one requirement which must be met to receive reinforcement, complex schedules are characterized by being a combination of two or more simple schedules. They can take on many different forms as you can see below.

First, the multiple schedule includes two or more simple schedules, each associated with a specific stimulus. For instance, a rat is trained to push a lever under a FR 10 schedule when a red light is on but to push the lever according to a VI 30 schedule when a white light is on. Reinforcement occurs after the condition for that schedule is met. So the organism receives reinforcement after the FR 10 and VI 30 schedules. Similar to a multiple schedule, a mixed schedule has more than one simple schedule, but they are not associated with a specific stimulus. The rat in our example could be under a FR 10 schedule for 30 seconds and then the VI 30 schedule for 60 seconds. The organism has no definitive way of knowing that the schedule has changed.

In a conjunctive schedule, two or more simple schedules must have their conditions met before reinforcement is delivered. Using our example, the rat would have to make 10 lever presses (FR 10) and a lever press after an average of 30 seconds has passed (VI 30) to receive a food pellet. The order that the schedules are completed in does not matter; just that they are completed.

In a chained schedule, a reinforcer is delivered after the last in a series of schedules is complete, and each schedule is controlled by a specific stimulus (a discriminative stimulus or SD). The chain must be completed in the pre-determined order. A rat could be on a FR 10 VR 15 FI 30 schedule, for instance. When a red light is on, the rat would learn to make 10 lever presses. Once complete, a green light would turn on and the rat would be expected to make an average of 15 lever presses before the light turns yellow indicating the FI 30 schedule is in effect. Once the 30 seconds are up and the rat makes a lever press, reinforcement occurs. Then the light turns red again indicating a return to the FR 10 schedule. Similar to the multiple-mixed schedule situation, this type of schedule can occur without the discriminative stimuli and is called a tandem schedule.

A schedule can also adjust such that after the organism makes 30 lever presses, the schedule changes to 35 presses, and then 40. So, the schedule moves from FR 30 to FR 35 to FR 40 as the organism demonstrates successful learning. Previous good performance leads to an expectation of even better performance in the future.

In an interesting twist on schedules, a cooperative schedule requires two organisms to meet the requirements together. If we place rats on a FR 30 schedule, any combination of 30 lever presses would yield food pellets. One rat could make 20 of the lever presses and the other 10 and both would receive the same reinforcement. Of course, we could make it a condition that both rats make 15 presses each, and it would not matter if one especially motivated rat makes more lever presses than the other. You might be thinking this type of schedule sounds familiar. It is the essence of group work whereby a group is to turn in, say, a PowerPoint presentation on borderline personality disorder. The group receives the same grade (reinforcer) no matter how the members chose to divide up the work.

Finally, a concurrent schedule presents an organism with two or more simple schedules at one time and it can choose which to follow. A rat may have the option to press a lever with a red light on a FR 10 schedule or a lever with a green light on a FR 20 schedule to receive reinforcement. Any guesses which one it will end up choosing? Likely the lever on the FR 10 schedule as reinforcement comes quicker.

Table 6.3. Comparison of Complex Schedules

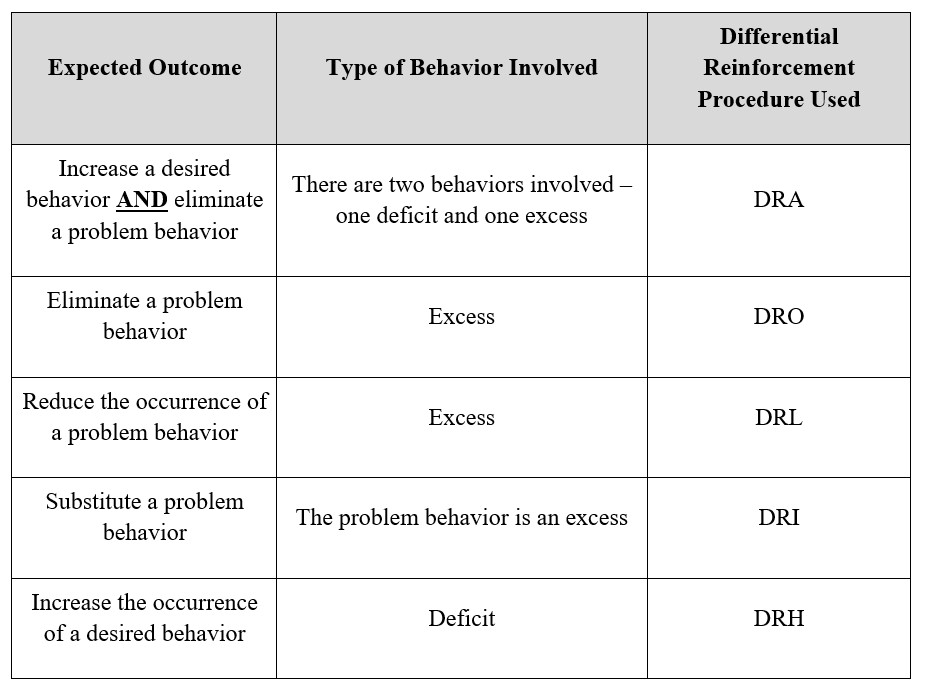

6.4.6. Differential Reinforcement

Consider the situation of a child acting out and the parent giving her what she demands. When this occurs, the parent has reinforced a bad behavior (a PR) and the tantrum ending reinforces the parent caving into the demand (NR). Now both parties will respond the same way when in the same situation (child sees a toy which is her antecedent to act out and the screaming child is the stimulus/antecedent for the parent to give the girl the toy). If the same reinforcers occur again, the behavior will persist. Most people near the interaction likely desire a different outcome. Some will want the parent to discipline the girl, but others might handle the situation more like this: these individuals will let the child have her tantrum and just ignore her. After a bit, the child should calm down and once in a more pleasant state of mind, ask the parent for the toy. The parent will praise the child for acting more mature and agree to purchase the toy, so long as the good behavior continues. This is an example of differential reinforcement in which we attempt to get rid of undesirable or problem behaviors by using the positive reinforcement of desirable behaviors. Differential reinforcement takes on many different forms.

6.4.6.1. DRA or Differential Reinforcement of Alternative Behavior — This is when we reinforce the desired behavior and do not reinforce undesirable behavior. Hence, the desired behavior increases and the undesirable behavior decreases to the point of extinction. The main goal of DRA is to increase a desired behavior and extinguish an undesirable behavior such as a student who frequently talks out of turn. The teacher praises the child in front of the class when he raises his hand and waits to be called on and does not do anything if he talks out of turn. Though this may be a bit disruptive at first, if the functional assessment reveals that the reinforcer for talking out of turn is the attention the teacher gives, not responding to the child will take away his reinforcer. This strategy allows us to use the reinforcer for the problem behavior with the desirable behavior. Eventually, the child will stop talking out of turn making the problem behavior extinct.

6.4.6.2. DRO or Differential Reinforcement of Other Behavior — What if we instead need to eliminate a problem behavior – i.e. reducing it down to no occurrences? DRO is the strategy when we deliver a reinforcer contingent on the absence of an undesirable behavior for some period. We will need to identify the reinforcer for the problem behavior and then pick one to use when this behavior does not occur. Determine how long the person must go without making the undesirable behavior and obtain a stopwatch to track the time. Do not reinforce the problem behavior and only reinforce the absence of it using whatever reinforcer was selected, and if it is gone for the full-time interval. If the problem behavior occurs during this time, the countdown resets. Eventually the person will stop making the undesirable behavior and when this occurs, increase the interval length so that the procedure can be removed.

For instance, if a child squirms in his seat, the teacher might tell him if he sits still for 5 minutes he will receive praise and a star to put on the star chart to be cashed in at a later time. If he moves before the 5 minutes is up, he has to start over, but if he is doing well, then the interval will change to 10 minutes, then 20 minutes, then 30, then 45, and eventually 60 or more. At that point, the child is sitting still on his own and the behavior is not contingent on receiving the reinforcer.

6.4.6.3. DRL or Differential Reinforcement of Low Rates of Responding — There are times when we don’t necessarily want to completely stop a behavior, or take it to extinction, but reduce the occurrence of a behavior. Maybe we are the type of person who really enjoys fast-food and eats it daily. This is of course not healthy, but we also do not want to go cold turkey on it. We could use DRL and decide on how many times each week we will allow ourselves to visit a fast-food chain. Instead of 7 times, we decide that 3 is okay. If we use full session DRL we might say we cannot exceed three times going to a fast-food restaurant in a week (defined as Mon to Sun). If we eat at McDonalds, Burger King, and Wendy’s three times on Monday but do not go again the rest of the week we are fine. Full session simply means you do not exceed the allowable number of behaviors during the specified time period. Eating fast-food three times in a day is definitely not healthy, and to be candid, gross, so a better approach could be to use spaced DRL. Now we say that we can go to a fast-food restaurant every other day. We could go on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday. This works because we have not exceeded 3 behaviors in the specified time of one week. If we went on Sunday too, this would constitute four times going to a fast-food restaurant and we would not receive reinforcement. Spaced DRL produces paced responding.

6.4.6.4. DRI or Differential Reinforcement of Incompatible Behavior — There are times when we need to substitute Behavior A with Behavior B such that by making B, we cannot make A. The point of DRI is to substitute a behavior. If a child is made to sit appropriately in his seat they cannot walk around the room. Sitting is incompatible with walking around. DRI delivers a reinforcer when another behavior is used instead of the problem behavior. To say it another way, we reinforce behaviors that make the undesirable or problem behavior impossible to make. DRI is effective with habit behaviors such as thumb sucking. We reinforce the child keeping his hands in his pocket. Or what if a man tends to make disparaging remarks at drivers who cut him off or are driving too slowly (by his standard). This might be a bad model for his kids, and so the man’s wife tells him to instead say something nice about the weather or hum a pleasant tune when he becomes frustrated with his fellow commuters. These alternative behaviors are incompatible with cursing and she rewards him with a kiss when he uses them.

6.4.6.5. DRH or Differential Reinforcement of High Rates of Responding. In this type of differential reinforcement, we reinforce a behavior occurring at a high rate or very often or seek to increase a behavior. Many jobs use this approach and reward workers who are especially productive by giving them rewards or special perks. For instance, I used to work for Sprint Long Distance when selling long distance to consumers was a thing. Especially good salespeople, such as myself, would win quarterly trips paid for 100% by Sprint and then the annual trip if we were consistent all year. We won the trips because we sold large numbers of long-distance plans, and other products such as toll-free numbers, in a designated period of time (every 3 months or every 12 months). Hence, a high rate of responding (i.e. engaging in the behavior of selling lots of plans) resulted in the reinforcement of quarterly or annual trips, and other benefits such as time off work and gift cards for local food establishments.

Table 6.4: Expected Outcome and Type of Differential Reinforcement to Use

6.5. Theories of Reinforcement

Section Learning Objectives

- Describe Hull’s drive reduction theory of reinforcement.

- Describe the Premack principle.

- Describe the response deprivation hypothesis.

6.5.1. Hull’s Drive Reduction Theory

Within motivation theory, a need arises when there is a deviation from optimal biological conditions such as not having enough calories to sustain exercise. This causes a drive which is an unpleasant state such as hunger or thirst and leads to motivated behavior. The purpose of this behavior, such as going to the refrigerator to get food or taking a drink from a water bottle, is to reduce or satisfy the drive. When we eat food, we gain the calories needed to complete a task or take a drink of water to sate our thirst. The need is therefore resolved. Hull (1943) said that any behavior we engage in that leads to a reduction of a drive is reinforcing and will be repeated in the future. So, if we walk to the refrigerator and get food which takes away the stomach grumbles associated with hunger, we will repeat this process in the future when we are hungry. Eating food to take away hunger exemplifies Negative Reinforcement.

Hull said there were two types of drives, which mirrors our earlier discussion of primary and secondary reinforcers and punishers. Primary drives are associated with innate biological needs states that are needed for survival such as food, water, urination, sleep, air, temperature, pain relief, and sex. Secondary drives are learned and are associated with environmental stimuli that lead to the reduction of primary drives, thereby becoming drives themselves. Essentially, secondary drives are like NS in respondent conditioning and become associated with primary drives which are US. They lead to a reduction in the uncomfortable state of hunger, thirst, being cold/hot, tired, etc. and so in the future we engage in such behavior when a need-drive arises. Hull said these S-R connections are strengthened the more times reinforcement occurs, and called this habit strength or formation (Hull, 1950). He wrote, “If reinforcements follow each other at evenly distributed intervals, everything else constant, the resulting habit will increase in strength as a positive growth function of the number of trials…” (pg. 175).

Though Hull presents an interesting theory of reinforcement, it should be noted that not all reinforcers are linked to the reduction of a drive. Sometimes we engage in a reinforcer for the sake of the reinforcer such as a child playing a video game because he/she enjoys it. No drive state is reduced in this scenario.

6.5.2. Premack Principle

Operant conditioning involves making a response for which there is a consequence. This consequence is usually regarded as a stimulus such that we get an A on an exam and are given ice cream by our parents (something we see, smell, and taste — YUMMY!!!!). But what if the consequence is actually a behavior? Instead of seeing the consequence as being presented, such as with the example of the stimulus of the ice cream, what if we really thought of it as being given the chance to eat ice cream which is a behavior (the act of eating)? This is the basic premise of the Premack principle, or more specifically, viewing reinforcers (the consequence) as behaviors and not stimuli, which leads to high-probability behavior being used to reinforce low-probability behavior (Premack, 1959). Consider that in many maze experiments, we obtain the behavior of running the maze (i.e. navigating through it from start to goal box) by food or water depriving a rat the night before. The next day the rat wants to eat something and to do so it needs to complete the maze. The maze running is our low probability behavior (or the one least likely to occur and the one the rat really does not want to do) and upon finishing the maze the rat is allowed to eat food pellets (the consequence of the behavior of running and the high probability behavior, or the one most likely to occur as the rat is hungry). Eating (high) is used to reinforce running the maze (low) and both are behaviors.

Sometimes I wake up in the morning and am excited to go to the gym (high probability behavior) but I know if I don’t eat something (the low probability behavior) before I go, I will not have a good work out. So, I eat something (low) and then get to go to the gym to run on the treadmill (the consequence and high probability behavior). For me, going to the gym reinforced eating breakfast.

6.5.3. Response Deprivation Hypothesis

A third theory of reinforcement comes from Timberlake and Allison (1974) and states that a behavior becomes reinforcing when an organism cannot engage in the behavior as often as it normally does. In other words, the response deprivation hypothesis says that the behavior falls below its baseline or preferred level. Let’s say my son likes to play video games and does so for about two hours each night after his homework is done (of course). What if I place a condition on his playing that he must clean up after dinner each night, to include doing the dishes and taking out the trash. He will be willing to work to maintain his preferred level of gameplay. He will do dishes and take the trash out so he can play his games for 2 hours. You might even say that a condition was already in place — doing homework before playing games. The games are reinforcement for the behavior of doing homework….and then later cleaning up after dinner….and this situation represents a contingency (If-Then scenario). If my son does not do his chores, then he will not be allowed to play games, resulting in his preferred level falling to 0.

Consider that the Premack principle and relative deprivation hypothesis are similar to one another in that they both establish a contingency. For the Premack principle, playing video games is a high probability behavior and doing chores such as cleaning up after dinner is a low probability behavior. My son will do the chores (low) because he gets to play video games afterward (high). So high reinforces the occurrence of low. The end result is the same as the response deprivation hypothesis. How these ideas differ is in terms of what is trying to be accomplished. In the Premack principle scenario, we are trying to increase the frequency of one behavior in relation to another while in the case of the relative deprivation hypothesis we are trying to increase one behavior in relation to its preferred level.

It’s time to take a break and rest. Module 6 is long, and you need your cognitive resources.

Try playing Candy Crush for fun!!!

See you in a bit.

6.6. Stimulus Control

Section Learning Objectives

- Define and exemplify stimulus control.

- Define stimulus discrimination.

- Define and describe discrimination training.

- Define and clarify why stimulus generalization is necessary.

- Describe generalization training and the strategies that can be used.

- Revisit the definition of discriminative stimuli.

- Clarify how stimuli or antecedents become cues.

- List and describe the 6 antecedent manipulations.

- Define prompts.

- List, describe, and exemplify the four types of prompts.

- Define fading.

- List and describe the two major types of fading and any subtypes.

- Define and exemplify shaping.

- Outline steps in shaping.

6.6.1. Stimulus Control

When an antecedent (i.e. stimulus) has been consistently linked to a behavior in the past, it gains stimulus control over the behavior. It is now more likely to occur in the presence of this specific stimulus or a stimulus class, defined as antecedents that share similar features and have the same effect on behavior. Consider the behavior of hugging someone. Who might you hug? A good answer is your mother. She expects and appreciates hugs. Your mother is an antecedent to which hugging typically occurs. Others might include your father, sibling(s), aunts, uncles, cousins, grandparents, spouse, and kids. These additional people fall under the stimulus class and share a similar feature of being loved ones. You could even include your bff. What you would not do is give the cashier at Walmart a hug. That would just be weird.

Do you stop when you get to a red octagonal sign? Probably, and the Stop sign has control over your behavior. In fact, you do not even have to think about stopping. You just do so. It has become automatic for you. The problem is that many of the unwanted behaviors we want to change are under stimulus control and happen without us even thinking about them. These will have to be modified for our desired behavior to emerge.

6.6.2. Stimulus Discrimination

We have established that we will cease all movement of our vehicle at a red octagonal stop sign and without thinking. A reasonable question is why don’t we do this at a blue octagonal sign, ignoring the fact that none exist? Stimulus discrimination is the process of reinforcing a behavior when a specific antecedent is present and only it is present. We experience negative reinforcement when we stop at the red octagonal sign and not a sign of another color, should a person be funny and put one up. The NR, in this case, is the avoidance of something aversive such as an accident or ticket, making it likely that we will obey this traffic sign in the future.

Discrimination training involves the reinforcement of a behavior when one stimulus is present but extinguishing the behavior when a different stimulus is present. From the example above, the red stop sign is reinforced but the blue one is not.

In discrimination training we have two stimuli:

- The SD or discriminative stimulus whose behavior is reinforced.

- and an SΔ (S-delta) whose behavior is not reinforced and so is extinguished.

When a behavior is more likely to occur in the presence of the SD and not the SΔ, we call this a discriminated behavior. And this is where stimulus control comes in. The discriminated behavior should be produced by the SD only. In terms of learning experiments, we train a pigeon to peck an oval key but if he pecks a rectangular one, no reinforcer is delivered.

6.6.3. Stimulus Generalization

As a stimulus can be discriminated, so too can it be generalized. Stimulus generalization is when a behavior occurs in the presence of similar, novel stimuli and these stimuli can fall on a generalization gradient. Think of this as an inverted u-shaped curve. The middle of the curve represents the stimulus that we are training the person or animal to respond to. As you move away from this stimulus, to the left or right, the other stimuli become less and less like the original one. So, near the top of the inverted U, a red oval or circle will be like a red octagon but not the same. Near the bottom of the curve, you have a toothbrush that has almost zero similarity to a stop sign.

In behavior modification (the applied side of learning), we want to promote generalization meaning that if we teach someone how to make a desirable response in a training situation, we want them to do that in all relevant environments where that behavior can occur, whether that be a child in a classroom, at home at the dinner table or in his/her bedroom, on the playground at recess, at the park, with the grandparents, etc. This is called generalization training and is when we reinforce behavior across situations until generalization occurs for the stimulus class. The desirable behavior should generalize from the time with a therapist or applied behavior analyst and to all other situations that matter. To make this happen you could/should:

- Always reinforce when the desirable behavior is made outside of training. By doing this, the desirable behavior is more likely.

- Teach other people to reinforce the desirable behavior such as teachers and caregivers. The therapist cannot always be with the client and so others have to take control and manage the treatment plan. Be sure they are trained, understand what to reinforce, and know what the behavioral definition is.

- Use natural contingencies when possible. Let’s say you are trying to teach social skills to a severely introverted client. In training, she does well and you reinforce the desirable behavior. Armed with new tactics for breaking the ice with a fellow student in class, she goes to class the next day and strikes up a conversation about the weather or the upcoming test. The fellow student’s response to her, and the continuation of the conversation, serve as reinforcers and occur naturally as a byproduct of her initiating a conversation. Another great example comes from a student of mine who was trying to increase her behavior of eating breakfast before class. She discovered that she felt more alert and energetic when she ate breakfast then when she did not, which are positive reinforcers, and naturally occurring. In fact, she was so happy about this, she jumped four goals and went from her initial goal of eating before class two times a week, to eating breakfast 6-7 times a week. Her behavior generalized beyond simply eating before class to eating breakfast every day when she woke up. It should be noted that her distal goal was 5 days, so in her first week of treatment she had already exceeded this goal. Way to go.

- Practice making the desirable response in other environments during training. You can achieve this by imagining these environments, role-playing, or setting up the environments to some extent.

- Related to the previous strategy, use common stimuli that are present in other environments as much as possible. An example is a stuffed animal that a child has at home. Or have the special education teacher bring the child’s desk to the training environment and have them sit in it.

- Encourage the client to use cues to make the desirable response outside of the training environment. These are reminders to engage in the correct behavior and can be any of the antecedent manipulations already discussed.

6.6.4. Stimulus Control Procedures: Antecedent Manipulations

One critical step is to exert control over the cues for the behavior and when these cues bring about a specific behavior, which, if you recall, are termed discriminative stimuli (also called an SD). So, what makes an antecedent a cue for a behavior? Simply, the behavior is reinforced in the presence of the specific stimulus and not reinforced when the stimulus or antecedent is not present.

The strategies we will discuss center on two ideas: we can modify an existing antecedent or create a new one. With some abusive behaviors centered on alcohol, drugs, nicotine, or food, the best policy is to never even be tempted by the substance. If you do not smoke the first cigarette, eat the first donut, take the first drink, etc. you do not have to worry about making additional problem behaviors. It appears that abstinence is truly the best policy.

But what if this is not possible or necessary? The following strategies could be attempted:

- Create a Cue for the Desirable Behavior — If we want to wake up in the morning to go to the gym, leave your gym clothes out and by the bed. You will see them when you wake up and be more likely to go to the gym. If you are trying to drink more water, take a refillable water bottle with you to classes. Hiking around campus all day can be tough and so having your water bottle will help you to stay hydrated.

- Remove a Cue for the Undesirable or Problem Behavior — In this case, we are modifying an existing antecedent/cue. Let’s say you wake up in the morning, like I do, and get on your phone to check your favorite game. You initially only intend to spend a few minutes doing so but an hour later you have done all the leveling up, resource collecting, candy swiping, structure building, etc. that you can and now you do not have the time to do a workout. In this case, phone use is a problem behavior because it interferes or competes with the execution of the desirable behavior of going to the gym. What do you do? There is a simple solution – do not leave your phone by your bed. If it is not in the room, it cannot be a reminder for you to engage in the problem behavior. The phone usage in the morning already exists as a behavior and the phone serves as a cue for playing games. You enjoy playing the games and so it is reinforcing. If the phone is not present, then the behavior of playing the game cannot be reinforced and the cue loses its effectiveness. In the case of water, if we do not carry tea with us, we cannot drink it, but can only drink our water bottle, thereby meeting our goal.

- Increasing the Energy Needed to Make a Problem Behavior — Since the problem behavior already exists and has been reinforced in the past, making its future occurrence likely in the presence of the stimulus, the best bet is to make it really hard to make this unwanted behavior. Back to the gym example. We already know that our phone is what distracts us and so we remove the stimuli. One thing we could do is place the phone in the nightstand. Out of sight. Out of mind, right? Maybe. Maybe not. Since we know the phone is in the nightstand, we could still pull it out in the morning. If that occurs, our strategy to remove the cue for phone usage fails. We can still remove it, but instead of placing it in the nightstand, place it in the living room and inside our school bag. So now it is out of sight, out of mind, but also far away which will require much more physical energy to go get than if it was in the nightstand beside us. Think about this for a minute. The strategy literally means that we expend more energy to do the bad behavior, than…..

- Decreasing the Energy Needed to Engage in the Desirable Behavior — …we would for the good behavior. Having our clothes by our bed is both a cue to go to the gym, but also, by having them all arranged in one place, we do not have to spend the extra time and energy running around our bedroom looking for clothes. We might also place our gym bag and keys by the door which saves us energy early in the morning when we are rushing out to the gym. What about for drinking water? Instead of carrying a water bottle with us we could just drink water from the water fountains at school. Okay. But let’s say that you are standing in the hallway and the nearest water fountain is all the way up the hallway and near the door to exit the building. You have to walk up the hall, bend over, push the button, drink the water, remove your hand from the fountain, walk back down the hall, re-enter the classroom, and then take your seat. Not too bad, right? WRONG. If you had your water bottle in your backpack, you would only need to reach down, pick it up, open the bottle, take a drink, cap the bottle, and set it back down on the floor or on the desk. You never have to leave your seat which means you are making far fewer behaviors in the overall behavior of drinking water, and so expending much less energy. Now you can use this energy for other purposes such as taking notes in class and raising your hand to ask a question.

Another way you can look at antecedents is to focus on the consequences. Wait. What? Why would that be an antecedent manipulation? Consider that we might focus on the motivating properties of the consequence so that in the future, we want to make the behavior when the same antecedent is present. Notice the emphasis on want. Remember, you are enhancing the motivating properties. How do we do this? From our earlier discussion, we know that we can use the motivating operations of establishing and abolishing operations. See Section 6.3.5 for the discussion. But they make up the last two antecedent manipulations that can be employed to bring about the desired behavior.

6.6.5. Transfer of Stimulus Control: Prompting and Fading

One way to help a response occur is to use what are called prompts, or a stimulus that is added to the situation and increases the likelihood that the desirable response will be made when it is needed. The response is then reinforced. There are four main types of prompts:

- Verbal — Telling the person what to do

- Gestural — Making gestures with your body to indicate the correct action the person should engage in

- Modeling — Demonstrating for the person what to do

- Physical — Guiding the person through physical contact to make the correct response

These are all useful and it is a safe bet to say that you have experienced all of them at some point. How so? Let’s say you just started a job at McDonald’s. You were hired to work the cash register and take orders. On your first day, you are assigned a trainer and she walks you through what you need to do. She might give you verbal instructions as to what needs to be done and when, and how to work the cash register. As you are taking your first order on your own, you cannot remember which menu the Big Mac meal fell under. She might point in the right area which would be making a gesture. Your trainer might even demonstrate the first few orders before you take over so that you can model or imitate her later. And finally, if you are having problems, she could take your hand and touch the Big Mac meal key, though this may be a bit aversive for most and likely improper. The point is that the trainer could use all of these prompts to help you learn how to take orders from customers. Consider that the prompts are in a sort of order from the easiest or least aversive (verbal) to the hardest or most aversive (physical). This will be important in a bit.

It is also prudent to reinforce the person when they engage in the correct behavior. If you told the person what to do, and they do it correctly, offer praise right away. The same goes for them complying with your gesture, imitating you correctly, or subjecting themselves to a physical and quite intrusive or aversive prompt.

When you use prompts, you also need to use what is called fading, which is the gradual removal of the prompt(s) once the behavior continues in the presence of the SD. Fading establishes a discrimination in the absence of the prompt. Eventually, you transfer stimulus control from the prompt to the SD.

Prompts are not a part of everyday life. Yes, you use them when you are in training, but after a few weeks, your boss expects you to take orders without even a verbal prompt. To get rid of prompts, you can either fade or delay the prompts. Prompt fading is when the prompt is gradually removed as it is no longer needed. Fading within a prompt means that you use just one prompt and once the person has the procedure down, you stop giving them a reminder or nudge. Maybe you are a quick study, and the trainer only needs to demonstrate the correct procedure once (modeling). The trainer would simply discontinue use of the prompt.

You can also use what is called fading across prompts. This is used when two or more prompts are needed. Maybe you are trying to explain an algebraic procedure to your child who is gifted in math. You could start with a verbal prompt and then move to gestural or modeling if he/she has a bit of an issue. Once the procedure is learned, you would not use any additional prompts. You are fading from least to most intrusive. But your other child is definitely not math-oriented. In this case, modeling would likely be needed first and then you could drop down to gestural and verbal. This type of fading across prompts moves from most to least intrusive. Finally, prompt delay can be used and is when you present the SD and then wait for the correct response to be made. You delay delivering any prompts to see if the person engages in the desirable behavior on their own. If he or she does, then no prompt is needed, but if not, then you use whichever prompt is appropriate at the time. For instance, you might tell your child to do the next problem and then wait to see if he/she can figure it out on their own. If not, you use the appropriate prompt.

6.6.6. Shaping

Sometimes there is a new(ish) behavior we want a person or animal to make but they will not necessarily know to make it, or how to make it. As such, we need to find a way to mold this behavior into what we want it to be. The following example might sound familiar to you. Let’s say you want a friend to turn on the lights in the kitchen. You decide not to tell them this by voice but play a game with them. As they get closer to the light switch you say “Hot.” If they turn away or do not proceed any further, you say “Cold.” Eventually, your statements of “Hot” will lead them to the switch and they will turn it on which will lead to the delivery of a great big statement of congratulations. “Hot” and “Thank you” are reinforcers and you used them to make approximations of the final, desired behavior of turning on the light. We called this ‘hot potato-cold-potato’ when we were a kid but in applied behavior analysis, this procedure is called shaping by successive approximations or shaping for short.

To use shaping, do the following:

- Identify what behavior you want the person or animal to make. Be sure you create a precise and unambiguous behavioral definition.

- Determine where you want them to start. This can be difficult but consider what others have done for the same problem behavior. When all else fails, start very low and make your steps small. More frequent reinforcement will help you too.

- Determine clear shaping steps; the successive approximations of the final behavior.

- Identify a reinforcer to use and reinforce after reaching the end of each step. This steady delivery of reinforcers, due to successfully moving to the next step, is what strengthens the organism’s progression to the final, target behavior.

- Continue at a logical pace. Don’t force the new behavior on the person or animal.

For shaping to work, the successive approximations must mimic the target behavior so that they can serve as steps toward this behavior. Skinner used this procedure to teach rats in a Skinner box (operant chamber) to push a lever and receive reinforcement. This was the final behavior he desired them to make and to get there, he had them placed in the box and reinforced as they moved closer and closer to the lever. Once at the lever the rat was only reinforced when the lever was pushed. Along the way, if the rat went back into parts of the chamber already explored it received no reinforcement. The rat had to move to the next step of the shaping procedure. We use the shaping procedure with humans in cases such as learning how to do math problems or learning a foreign language.

We are almost finished with our coverage of operant conditioning. Before moving onto the final two sections, take a break. Section 6.6 was pretty long and full of a ton of information. Go do something fun, get some food, take a nap, etc. but return once you head is clear, and you are ready to finish up.

6.7. Aversive Control — Avoidance and Punishment

Section Learning Objectives

- Describe the discriminated avoidance procedure.

- Contrast avoidance and escape trials.

- Contrast two-process and one-process theories of avoidance.

- Revisit what forms punishment can take.

- Define and exemplify time outs.

- Clarify what a response cost is.

- Define overcorrection.

- Describe contingent exercise, physical restraint, and guided compliance.

- Compare the various theories of punishment.

- Clarify what the problems are with punishment.

- Clarify what the benefits of punishment are.

- Explain how to use punishment effectively.

6.7.1. Discriminated Avoidance Procedure