Module 5: Applications of Respondent Conditioning

Module Overview

Having covered basic and advanced topics in relation to respondent conditioning, also called classical or Pavlovian conditioning, I will now present some applications of the learning model in the real world. To that end we will discuss the acquisition of fears (phobias) from a clinical psychology perspective, the paradigm of eyeblink conditioning, how food preferences and taste aversions are learned, PTSD and treatment approaches, and advertising and its use of the learning model.

Module Outline

- 5.1. Fear Conditioning

- 5.2. Eyeblink Conditioning

- 5.3. Taste Aversion

- 5.4. Food Preferences

- 5.5. PTSD

- 5.6. Advertising

Module Learning Outcomes

- Describe how fears are learned and unlearned using respondent conditioning.

- Describe the use of the eyeblink conditioning procedure in respondent conditioning.

- Clarify how taste aversion occurs.

- Clarify how we acquire food preferences.

- Describe how respondent conditioning can be used to partially explain and treat PTSD.

- Propose ways to use respondent conditioning in advertising/marketing.

5.1. Fear Conditioning

Section Learning Objectives

- Describe how fears are learned citing the Watson and Rayner (1920) study.

- Outline factors affecting fearfulness.

- Describe phobias in general and then specific types from the perspective of clinical psychology.

- Describe the counterconditioning method.

- Describe exposure treatments.

- Describe flooding.

- Outline the conditioned emotional response (CER) technique.

- Define the suppression ratio.

5.1.1. Learning Phobias

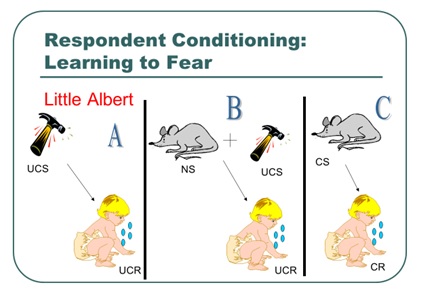

One of the most famous studies in psychology was conducted by John B. Watson and graduate student Rosalie Rayner (1920). Essentially, they wanted to explore the possibility of conditioning various types of emotional responses. The researchers ran a 9-month-old child, known as Little Albert, through a series of trials in which he was exposed to a white rat to which no response was made outside of curiosity (NS — no response not shown).

In Panel A of Figure 10.2, we have the naturally occurring response to the stimulus of a loud sound. On later trials, the rat was presented (NS) and followed closely by a loud sound as Albert touched it (US; Panel B). In the first trial, Albert “jumped violently and fell forward, burying his face in the mattress. He did not cry, however” (pg. 4). In subsequent trials, his reaction was similar except that he whimpered. The level of fear he displayed to the rat increased over conditioning trials, resulting in the child responding with fear to the mere presence of the white rat (Panel C). It should be noted that Little Albert’s fear of the rat generalized to similar objects such as a Santa Claus mask, a fur coat, a rabbit, and a dog.

To read the Watson and Rayner (1920) article entitled, “Conditioned Emotional Reactions,” for yourself, please visit: https://psychclassics.yorku.ca/Watson/emotion.htm

Figure 5.1. Learning to Fear

Note: UCS is the same as US and UCR is the same as UR

5.1.1.1. Factors affecting fearfulness. Several factors affect the degree to which a person or animal will become fearful. First, Seligman (1971) proposed the idea of biological preparedness which says that organisms tend to learn some associations more readily than others. One reason why this might occur is that these more easily learned CS-US relationships aid in survival and is one reason why we might learn to avoid a hot stove quicker than a butterfly. In a classic study, rhesus monkeys were shown videotapes of model monkeys exhibiting either an intense fear or no fear of fear-relevant stimuli (toy snakes or a toy crocodile) or to fear-irrelevant stimuli (flowers or a toy rabbit). The observer monkeys were placed into one of four conditions (fear reaction with fear-relevant stimuli; no fear reaction with fear-relevant stimuli; fear reaction with fear-irrelevant stimuli; no fear reaction with fear-irrelevant stimuli) for 12 sessions. Results showed that the observer monkeys acquired a fear of fear-relevant stimuli but not the fear-irrelevant stimuli. Hence, they were prepared to learn to fear snakes or crocodiles before flowers or rabbits (Cook & Mineka, 1989).

Another factor involves the organism’s temperament or base level of emotionality and reactivity to stimulation. Temperament can, therefore, affect how easily a CR, such as fear, can be acquired (Clark, Watson, & Minkeka, 1994). Young infants display three types of temperament. Easy children are happy, have regular sleep and eating habits, are adaptable and calm, and not easily upset. Difficult children have irregular feeding and eating habits, are fearful of new people and situations, fussy, easily upset by noise and stimulation, and intense in their reactions. Finally, slow to warm children are less active and fussy, withdraw and react negatively to new situations, but over time may become more positive with repeated exposure to novel people, objects, and situations.

Third, having a history of control over events in our lives immunizes an organism from displaying elevated fear when faced with new stimuli. Before 6 months of age, infants are not upset by the presence of people they do not know. As they learn to anticipate and predict events, strangers cause anxiety and fear. This is called stranger anxiety. Not all infants respond to strangers in the same way though. Infants with more experience show lower levels of anxiety than infants with little experience. Also, infants are less concerned about strangers who are female and those who are children. The latter probably has something to do with size as adults may seem imposing to children.

Finally, modeling is another behavioral explanation of the development of fears. In modeling, an individual acquires a fear though observation and imitation (Bandura & Rosenthal, 1966). For example, when a young child observes their parent display irrational fears of an animal, the child may then begin to display similar behaviors. Similarly, observing another individual being ridiculed in a social setting may increase the chances of the development of social anxiety, as the individual may become fearful that they would experience a similar situation in the future. It is speculated that the maintenance of these phobias is due to the avoidance of the feared item or social setting, thus preventing the individual from learning that the item/social situation is not something that should be feared. We will talk more about modeling in Module 8.

While modeling and classical conditioning largely explain the development of phobias, there is some speculation that the accumulation of a large number of these learned fears will develop into Generalized Anxiety Disorder, a disorder characterized by an underlying excessive worry related to a wide range of events or activities. Through stimulus generalization, a fear of one item (such as a dog) may become generalized to other items (such as all animals). As these fears begin to grow, a more generalized anxiety will appear, as opposed to a specific phobia.

5.1.2. Respondent Conditioning Approaches to Treating Phobias (and Anxiety Disorders)

5.1.2.1. Phobias from the perspective of clinical psychology. Before we discuss treating phobias, a distinction is needed. The hallmark symptoms of anxiety-related disorders are excessive fear or anxiety related to behavioral disturbances. Fear is considered an adaptive response, as it often prepares your body for an impending threat. Anxiety, however, is more difficult to identify as it is often the response to a vague sense of threat. The two can be distinguished from one another as fear is related to either a real or perceived threat, while anxiety is the anticipation of a future threat (APA, 2013). So what form can phobias take?

Specific phobia is distinguished by an individual’s fear or anxiety specific to an object or a situation. While the amount of fear or anxiety related to the specific object or situation varies among individuals, it also varies related to the proximity of the object/situation. When individuals are face-to-face with their specific phobia, immediate fear is present. It should also be noted that these fears are more excessive and more persistent than a “normal” fear, often severely impacting one’s daily functioning (APA, 2013).

Individuals can experience multiple specific phobias at one time. In fact, nearly 75% of individuals with a specific phobia report fear in more than one object (APA, 2013). When making a diagnosis of specific phobia, it is important to identify the specific phobic stimulus. Among the most commonly diagnosed specific phobias are animals, natural environments (height, storms, water), blood-injection-injury (needles, invasive medical procedures), or situational (airplanes, elevators, enclosed places; APA, 2013). Given the high percentage of individuals who experience more than one specific phobia, all specific phobias should be listed as a diagnosis in efforts to identify an appropriate treatment plan.

Agoraphobia is defined as an intense fear triggered by a wide range of situations. Agoraphobia’s fears are related to situations in which the individual is in public situations where escape may be difficult. In order to receive a diagnosis of agoraphobia, there must be a presence of fear in at least two of the following situations: using public transportation such as planes, trains, ships, buses; being in large, open spaces such as parking lots or on bridges; being in enclosed spaces like stores or movie theaters; being in a large crowd similar to those at a concert; or being outside of the home in general (APA, 2013). When an individual is in one (or more) of these situations, they experience significant fear, often reporting panic-like symptoms (see Panic Disorder below). It should be noted that fear and anxiety-related symptoms are present every time the individual is presented with these situations. Should symptoms only occur occasionally, a diagnosis of agoraphobia is not warranted.

Due to the intense fear and somatic symptoms, individuals will go to great lengths to avoid these situations, often preferring to remain within their home where they feel safe, thus causing significant impairment of one’s daily functioning. They may also engage in active avoidance, where the individual will intentionally avoid agoraphobic situations. These avoidance behaviors may be behavioral, including having food delivered to avoid going to the grocery store or only taking a job that does not require the use of public transportation, or cognitive, by using distraction and various other cognitive techniques to successfully get through the agoraphobic situation.

For social anxiety disorder, the anxiety is directed toward the fear of social situations, particularly those in which an individual can be evaluated by others. More specifically, the individual is worried that they will be judged negatively and viewed as stupid, anxious, crazy, boring, unlikeable, etc. Some individuals report feeling concerned that their anxiety symptoms will be obvious to others via blushing, stuttering, sweating, trembling, etc. These fears severely limit an individual’s behavior in social settings. For example, an individual may avoid holding drinks or plates if they know they will tremble in fear of dropping or spilling food/water. Additionally, if one is known to sweat a lot in social situations, they may limit physical contact with others, refusing to shake hands.

Unfortunately, for those with social anxiety disorder, all or nearly all social situations provoke this intense fear. Some individuals even report significant anticipatory fear days or weeks before a social event is to occur. This anticipatory fear often leads to avoidance of social events in some individuals; others will attend social events with a marked fear of possible threats. Because of these fears, there is a significant impact in one’s social and occupational functioning.

It is important to note that the cognitive interpretation of these social events is often excessive and out of proportion to the actual risk of being negatively evaluated. There are instances where one may experience anxiety toward a real threat such as bullying or ostracism. In this instance, social anxiety disorder would not be diagnosed as the negative evaluation and threat are real.

Panic disorder consists of a series of recurrent, unexpected panic attacks coupled with the fear of future panic attacks. A panic attack is defined as a sudden surge of fear or impending doom along with at least four physical or cognitive symptoms (listed below). The symptoms generally peak within a few minutes, although it seems much longer for the individual experiencing the panic attack.

There are two key components to panic disorder—the attacks are unexpected, meaning there is nothing that triggers them, and they are recurrent, meaning they occur multiple times. Because these panic attacks occur frequently and essentially “out of the blue,” they cause significant worry or anxiety in the individual as they are unsure of when the next attack will occur. In some individuals, significant behavioral changes such as fear of leaving their home or attending large events occur as the individual is fearful an attack will happen in one of these situations, causing embarrassment. Additionally, individuals report worry that others will think they are “going crazy” or losing control if they were to observe an individual experiencing a panic attack. Occasionally, an additional diagnosis of agoraphobia is given to an individual with panic disorder if their behaviors meet diagnostic criteria for this disorder as well.

The frequency and intensity of these panic attacks vary widely among individuals. Some people report panic attacks occurring once a week for months on end, others report more frequent attacks multiple times a day, but then experience weeks or months without any attacks. Intensity of symptoms also varies among individuals, with some patients reporting experiencing nearly all 14 symptoms and others only reporting the minimum 4 required for the diagnosis. Furthermore, individuals report variability within their panic attack symptoms, with some panic attacks presenting with more symptoms than others. It should be noted that at this time, there is no identifying information (i.e. demographic information) to suggest why some individuals experience panic attacks more frequently or more severely than others.

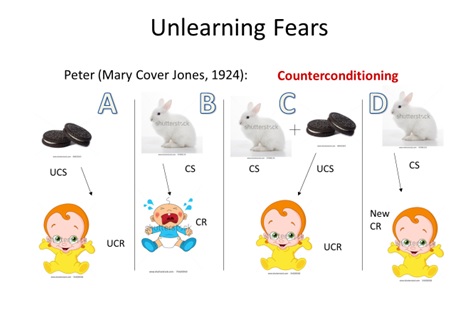

5.1.2.2. Counterconditioning. As fears can be learned, so too they can be unlearned. Consider the follow-up to Watson and Rayner (1920), Jones (1924; Figure 5.2), who wanted to see if a child who learned to be afraid of white rabbits (Panel B) could be conditioned to become unafraid of them. This direct conditioning method involved associating a fear-object with a stimulus/object that could arouse a positive (pleasant) reaction. The hunger motive was used in conjunction with the fear motive and the subject, Peter, was placed in a highchair and given something to eat during a period of food craving. The rabbit was brought to within 4 feet of Peter causing a negative response. But when he asked for the rabbit to be taken away, it was moved to 20 feet away. At this point, he stopped crying but did continue to fuss and said, “I want you to put Bunny outside.” Then, he resumed eating some pleasant food (i.e., something sweet such as cookies [Panel C]; remember the response to the food is unlearned, i.e., Panel A). Jones writes, “The relative strength of the fear impulse and the hunger impulse may be gauged by the distance to which it is necessary to remove the fear-object” (pg. 127). The procedure in Panel C continued with the rabbit being brought in a bit closer each time to eventually the child did not respond with distress to the rabbit (Panel D). Since Peter was one of her most serious problem cases, he was treated once or twice daily for nearly two months (from March 10 to about April 29) and at the mid-morning lunch since it almost always guaranteed some interest in the food. By the last days, he would ask, “Where is the rabbit?” It would be brought in and placed at his feet resulting in him petting, picking up (or at least trying), and playing with him for several minutes. The success of this method is conditional on hunger level, and as it grows so does the success of the method, at least to a certain point.

Figure 5.2. Unlearning Fears

To read the article for yourself, please visit: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/3859/cafa35c27d0abb0e6a9164186a9c05bb9034.pdf

5.1.2.3. Exposure treatments. While there are many treatment options for specific phobias, research routinely supports behavioral techniques as the most effective treatment strategies. Seeing as behavioral theory suggests phobias are developed via respondent conditioning, the treatment approach revolves around breaking the maladaptive association developed between the object and fear. This is generally accomplished through exposure treatments. As the name implies, the individual is exposed to their feared stimuli. This can be done in several different approaches: systematic desensitization, flooding, and modeling.

Systematic desensitization (Wolpe, 1961) is an exposure technique that utilizes relaxation strategies to help calm the individual as they are presented with the fearful object. The notion behind this technique is that both fear and relaxation cannot exist at the same time; therefore, the individual is taught how to replace their fearful reaction with a calm, relaxing reaction.

To begin, the patient, with assistance from the clinician, will identify a fear hierarchy, or a list of feared objects/situations ordered from least to most feared. After learning intensive relaxation techniques, the clinician will present items from the fear hierarchy, starting from the least feared object/subject, while the patient practices using the learned relaxation techniques. The presentation of the feared object/situation can be in person — in vivo exposure, or it can be imagined — imaginal exposure. Imaginal exposure tends to be less intensive than in vivo exposure; however, it is less effective than in vivo exposure in eliminating the phobia. Depending on the phobia, in vivo exposure may not be an option, such as with a fear of a tornado. Once the patient is able to effectively employ relaxation techniques to reduce their fear/anxiety to a manageable level, the clinician will slowly move up the fear hierarchy until the individual does not experience excessive fear of all objects on the list.

5.1.2.4. Flooding. Another respondent conditioning way to unlearn a fear is what is called flooding or exposing the person to the maximum level of stimulus and as nothing aversive occurs, the link between CS and UCS producing the CR of fear should break, leaving the person unafraid. That is the idea at least and if you were afraid of clowns, you would be thrown into a room full of clowns. Similar to systematic desensitization, flooding can be done in either in vivo or imaginal exposure. Clearly, this technique is more intensive than the systematic or gradual exposure to feared objects. Because of this, patients are at a greater likelihood of dropping out of treatment, thus not successfully overcoming their phobias. Flooding is an extinction procedure, and not a counterconditioning procedure, it should be noted.

5.1.2.5. Modeling. Finally, modeling is another common technique that is used to treat phobias (Kelly, Barker, Field, Wilson, & Reynolds, 2010). In this technique, the clinician approaches the feared object/subject while the patient observes. Like the name implies, the clinician models appropriate behaviors when exposed to the feared stimulus, implying that the phobia is irrational. After modeling several times, the clinician encourages the patient to confront the feared stimulus with the clinician, and then ultimately, without the clinician.

5.1.3. The Conditioned Emotional Response Technique (CER)

Behaviorists also use what is called the conditioned emotional response (CER) technique, or conditioned suppression. This method involves the following procedure:

- A rat is trained to press a bar in a Skinner box and for doing so, receives a food reward. This follows standard operant conditioning procedures described in Module 6.

- Once the level of pressing response is occurring at a regular rate, an NS is introduced in the form of a light, tone, or noise.

- The NS is paired with a US of a mild foot shock lasting about 0.5 seconds.

- This causes the UR of fear. Note that the bar pressing has nothing to do with the delivery of a shock or with the presentation of NS/CS and US.

- This pairing occurs several times (NS and US or light/tone/noise and shock) resulting in a CS leading to a CR. The CR, in this case, takes the form of the rat stopping pressing the bar or freezing. The CR is not the same as the UR (fear).

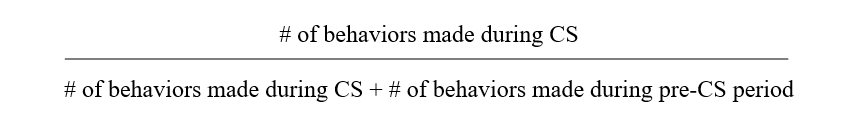

The procedure allows for the calculation of what is called the suppression ratio. The number of bar presses made during the CS are counted, as well as the number made during a period of equal length right before the CS, called the pre-CS period. The formula for suppression ratio is:

This ratio has a range of values from 0 to 0.5. A value of 0.5 indicates that the number of bar presses has not changed from the pre-CS to CS period. If 10 bar presses were made pre-CS this value would be the same during the CS. So, 10 /10+10 = 10/20 = 0.5. But what if suppression did occur and the number of bar presses falls to 5? The suppression ratio would be 5/5+10 or 5/15 = 0.33. If there was complete suppression, then: 0/0+10 = 0.00.

5.2. Eyeblink Conditioning

Section Learning Objectives

- Describe the eyeblink procedure used in respondent conditioning experiments.

Another application of respondent conditioning includes the eyeblink reflex. Rabbits are commonly used in this procedure as the stimulus and timing parameters that lead to optimal learning have been clearly worked out in them (Vogel et al., 2009). To start, rabbits are habituated to a stock that keeps them restrained. Exposure to brief (about a half-second) tones and light NS occur and are paired with the US of either a puff of air to the cornea of the eye or a mild electric shock near the eye, which causes the rabbit to blink (UR). With repeated pairings, the rabbit blinks (CR) to the tone/light (CS). Unlike other conditioning paradigms, the CR is easy to observe and measure and an interstimulus-interval (ISI) of about 200-500 ms is optimal for rabbit eyeblink conditioning (Schniderman & Gormezano, 1964).

Previous research has shown that the eyeblink response is supported by clear neural circuits such that the pairing of CS to US requires the cerebellum and interpositus nucleus specifically (Christian & Thompson, 2003). More recent research has confirmed changes in synaptic number or structure in the interpositus nuclei following eye-blink conditioning such that there was a significant increase in the length of the excitatory synapses in conditioned animals as well as an increase in synaptic number (Weeks et al., 2007).

5.3. Taste Aversion

Section Learning Objectives

- Describe the typical conditioned taste aversion paradigm.

- Clarify why such a ‘skill’ is needed.

Organisms will tend to reject a food type if it makes them nauseated. This basic idea was put forth by Garcia, Kimeldorf, and Koelling (1955) when they paired a solution of saccharin (CS), which rats generally prefer, with gamma radiation (US) which makes them sick (UR). Relatively quickly, the rats associated the saccharin solution (CS) with getting sick (CR) and avoided it. So how quick is quick? Well, a strong aversion can be learned in as little as one trial and the ISI can be several hours in length!!!

Why would this skill be needed? Welzl et al. (2000) writes, “To survive in a world with varying supplies of different foods animals have to learn which are safe and which are not safe to eat. Most foods are characterized by a specific flavor, i.e. a unique combination of taste and smell. Thus, learning which flavors signal ‘safe to eat’ and which ‘causes nausea’ is important for making use of all the safe foods while at the same time avoiding potentially hazardous ones. Taste is an especially critical information because if it signals ‘causes nausea’ the animal has a last chance to refrain from eating the food” (pg. 205).

Food for Thought — Why might an awareness and understanding of conditioned taste aversion be important in relation to cancer patients?

5.4. Food Preferences

Section Learning Objectives

- Discuss support for food preferences being learned.

In the previous section, we saw how we can learn to not like certain foods or to develop taste aversions. Likewise, we can develop a preference for certain foods through respondent conditioning. Across two experiments, Dickinson and Brown (2007) employed a sample of volunteer undergraduate students and induced flavor aversion by mixing banana and vanilla with a bitter substance (Tween20) and flavor preference by mixing the same neutral flavors with sugar. Results showed that students reported increased liking of the flavor that was paired with sugar and a reduced liking of the flavor paired with the bitter substance. These results fit into a body of literature suggesting the existence of evaluative conditioning or when our initial evaluation of a stimulus changes due to it being associated with another stimulus that we already like or dislike.

5.5. PTSD

Section Learning Objectives

- Define and outline the diagnostic criteria of PTSD.

- Describe respondent conditioning approaches to treating PTSD.

5.5.1. What is PTSD?

Posttraumatic stress disorder, or more commonly known as PTSD, is identified by the development of physiological, psychological, and emotional symptoms following exposure to a traumatic event. While the presentation of these symptoms varies among individuals, there are a few categories in which these symptoms present.

One category is recurrent experiences of the traumatic event. This can occur via flashbacks, distinct memories, or even distressing dreams. In order to meet the criteria for PTSD, these recurrent experiences must be specific to the traumatic event or the moments immediately following. The dissociative reactions can last a short time (several seconds) or extend for several days. They are often initiated by physical sensations similar to those experienced during the traumatic events, or even environmental triggers such as a specific location. Because of these triggers, individuals with PTSD are known to avoid stimuli (i.e. activities, objects, people, etc.) associated with the traumatic event.

Another symptom experienced by individuals with PTSD is negative alterations in cognitions or mood. Often individuals will have difficulty remembering an important aspect of the traumatic event. It should be noted that this amnesia is not due to a head injury, loss of consciousness, or substances, but rather, due to the traumatic nature of the event. Individuals may also have false beliefs about the causes of the traumatic event, often blaming themselves or others. Because of these negative thoughts, those with PTSD often experience a reduced interest in previously pleasurable activities.

Because of the negative mood and increased irritability, individuals with PTSD may be quick-tempered and act out in an aggressive manner, both verbally and physically. While these aggressive responses may be provoked, they are also sometimes unprovoked. It is believed these behaviors occur due to the heightened sensitivity to potential threats, especially if the threat is similar in nature to their traumatic event. More specifically, individuals with PTSD have a heightened startle response and easily jump or respond to unexpected noises such as a telephone ringing or a car backfiring.

Memory and concentration difficulties may also occur. Again, these are not related to a traumatic brain injury, but rather due to the physiological state the individual may be in as a response to the traumatic event. Given this heightened arousal state, it should not be surprising that individuals with PTSD also experience significant sleep disturbances, with difficulty falling asleep, as well as staying asleep due to nightmares.

Although somewhat obvious, these symptoms likely cause significant distress in social, occupational, and other (i.e. romantic, personal) areas of functioning. Duration of symptoms is also important, as PTSD cannot be diagnosed unless symptoms have been present for at least one month.

5.5.2. Respondent Conditioning Approaches to Treating PTSD

While exposure therapy is predominately used in anxiety disorders, it has also shown great assistance in PTSD related symptoms as it helps individuals extinguish fears associated with the traumatic event. There are several different types of exposure techniques — imaginal, in vivo, and flooding are among the most common types of exposure (Cahill, Rothbaum, Resick, & Follette, 2009).

In imaginal exposure, the individual is asked to re-create, or imagine, specific details of the traumatic event. The patient is then asked to repeatedly discuss the event in more and more detail, providing more information regarding their thoughts and feelings at each step of the event. With in-vivo exposure, the individual is reminded of the traumatic event through the use of videos, images, or other tangible objects related to the traumatic event, that induces a heightened arousal response. While the patient is re-experiencing cognitions, emotions, and physiological symptoms related to the traumatic experience, they are encouraged to utilize positive coping strategies, such as relaxation techniques to reduce their overall level of anxiety.

Imaginal exposure and in vivo exposure are generally done in a gradual process, with imaginal exposure beginning with few details of the event, and slowly gaining more and more information over time; in vivo starts with images/videos that elicit lower levels of anxiety, and then the patient slowly works their way up a fear hierarchy, until they are able to be exposed to the most distressing images. Another type of exposure therapy, flooding, involves disregard for the fear hierarchy, presenting the most distressing memories or images at the beginning of treatment. While some argue that this is a more effective treatment method, it is also the most distressing, thus placing patients at risk for dropping out of treatment (Resick, Monson, & Rizvi, 2008).

5.6. Advertising

Section Learning Objectives

- Clarify whether respondent conditioning can be used in advertising/marketing.

Could respondent conditioning be used in marketing and advertising? In a study of 202 business and psychology undergraduate students, Stuart et al. (1987) hypothesized that “Attitude toward a brand will be more positive for subjects following repeated conditioning trials in which a neutral CS (brand) is paired with a positively valenced US (a pleasant advertising component) than for subjects exposed to the neutral CS and the US in random order with respect to each other” (H1; pg. 336). Brand L toothpaste was presented several times and followed by pleasant scenes (a mountain waterfall, a sunset over an island, blue sky and clouds seen through the mast of a boat, and a sunset over the ocean) for an experimental group but followed by neutral scenes for a control group. The results showed that Brand L was rated significantly higher, or more positively, when paired with pleasant scenes. The authors conclude that “…conditioned learning of brand-specific attitudes is indeed demonstrable under laboratory conditions” (pg. 346).

Module Recap

In this module, we discussed six applications of respondent conditioning to include fear acquisition, the eyeblink paradigm, matters related to taste preferences and aversions, PTSD, and advertising. With this done, Part II is complete, and we now move to our discussion of the associative learning model of operant conditioning championed by Thorndike and Skinner.

Note to Student: To read more about PTSD and phobias from a clinical psychology perspective, please visit the Abnormal Psychology (2nd edition) Open Education Resource (OER) by Alexis Bridley and Lee W. Daffin Jr. at https://opentext.wsu.edu/abnormal-psych/. Excerpts were included in this book, though they may have been altered slightly to fit the content and context of a textbook on the principles of learning.

2nd edition