Module 6: Persuasion

Module Overview

The second section of the textbook covered the three main ways we better understand ourselves and others. That knowledge gives us a solid base that helps us navigate our world. The next section will look at how we influence and are influenced by others. Everything we have already learned will continue to be built upon as we now come to understand persuasion, conformity and group influence. In the last module on attitudes, we learned that our evaluation of things, or our attitudes, can be changed, sometimes by our own inconsistencies, but often through persuasive communication attempts. This module will focus on those persuasive communication attempts as well as our attempts to persuade others. We will focus on how we process these attempts, when they are most successful, and how we can resist them.

Module Outline

- 6.1. Processing Persuasive Communication

- 6.2. Factors that Lead to Successful Persuasion

- 6.3. A Closer Look at Cults: Dangers and Resistance to Persuasion

Module Learning Outcomes

- Explore the idea that we have a persuasion schema or bag of tricks for persuading and being persuaded by others

- Explain how we process persuasive attempts through the dual processing models

- Investigate what characteristics make a communicator more or less persuasive, specifically focusing on credibility and attractiveness

- Explore types of messages that successfully persuade

- Clarify the danger of cults and how we can resist being persuaded by them

6.1. Processing Persuasive Communication

Section Learning Objectives

- Explore the persuasive schema perspective.

- Describe the dual processing models.

6.1.1. Persuasion Schema

We spend our days persuading and being persuaded. You may have just emailed your teacher asking for an extension or tried to get your child to eat their lunch. You might also have had two ads pop up while you were on Facebook: one is for this amazing new bra and another one is for a blanket for your daughter that looks like a mermaid tail. Persuasion serves an important function in a social society. If you are not successful in persuading others, you could miss out on job opportunities or have poor relationships or no relationships. If you are unaware of persuasion attempts, then you could be taken advantage of.

For Further Consideration

Take a moment and think about who tries to persuade you on a daily basis and whom do you try to persuade. Make a list of these people. What kinds of things do people persuade other people (their friends, their family, or their enemies) to do? What are the different techniques people use to get these people to do what they want?

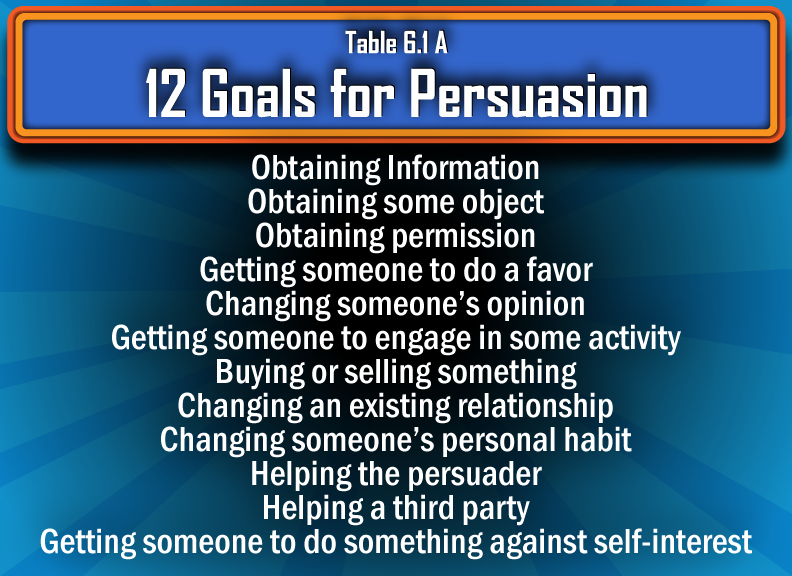

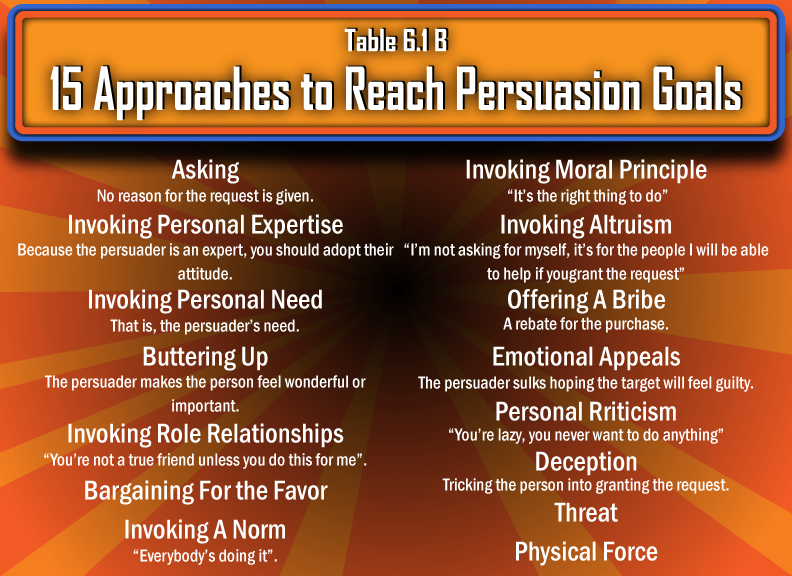

A research study done by Rule, et al., (1985) set out to determine if we have a persuasion schema or package of behaviors (tricks) for how we persuade people and are persuaded by them. They completed three different studies to find these answers. In the first study, they asked participants to report whom they persuaded and who persuaded them. They found that students reported others were persuading them more than they were persuading other people. When asked how they persuaded others a list of 12 reasons/goals was generated. You can see this list in Table 6.1a. How do these responses match with your answers from above? Are they similar/different? In the second study they took this list of 12 reasons/goals for persuading and asked the participants to write all the ways that they could achieve these persuasion goals and then rank them by most likely to use. In Table 6.1b you will find the 15 different approaches. They found that it didn’t matter who was persuading or being persuaded. There seems to be a standard order of persuasive strategies. How do your responses fit with the second table? Do your answers fit the research findings?

6.1.2 Dual-Processing Models and How We Process Persuasion

Our days are spent navigating the enormous amounts of information that are being sent our way. We get up in the morning and the radio DJ tells us about the latest news stories. We check our email and we have 13 new emails from co-workers, family, friends and in my case, students. Our social media is full of advertisements trying to sell us the latest products, and as we drive around town there are billboards advertising stores and the local college football team. Which of these pieces of information or persuasion attempts will be successful? Which ones will persuade us to do something, to buy something or to change our attitude about something? The first step in understanding persuasion is to examine how we process or think about these persuasive attempts.

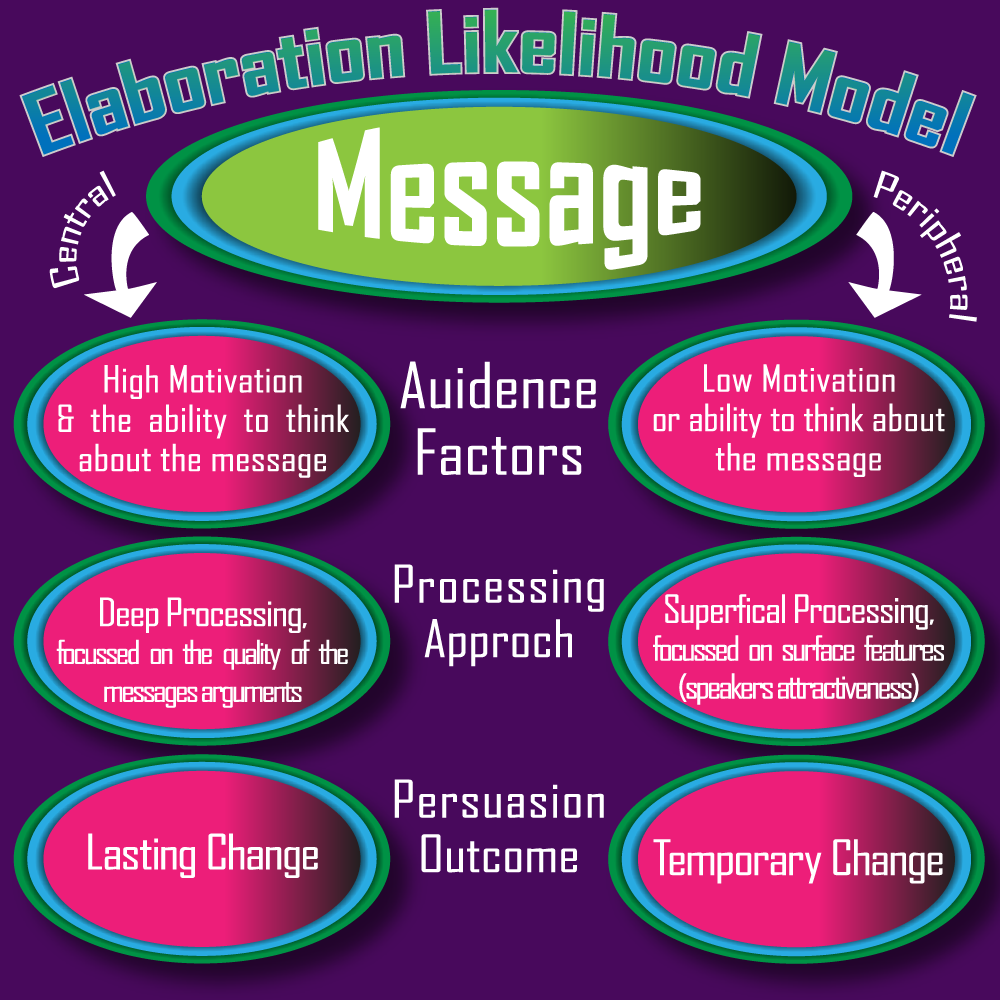

It is impossible to spend a lot of time thinking about all the information that we are bombarded with — we would be driven mad or pushed to mental exhaustion. So, as motivated tacticians, Chaiken et al., (1989), says we will be very selective of the moments we use our limited cognitive resources. This small set of information that we select will be fully analyzed and investigated. Everything else we come into contact with will be responded to automatically. We won’t spend much time thinking or considering, but rather automatically responding using our mental shortcuts or heuristics that are triggered from the context of the information. Is the person presenting the information attractive? We have a “What is beautiful-is-good” heuristic — this mental shortcut results in us automatically connecting the source’s attractiveness with the qualities of being good, kind, smart, etc. For example, Ted Bundy, the serial killer, was considered attractive and would lure women to their deaths by asking for help. The women he asked were happy to help. They automatically responded to the “what is beautiful-is-good” heuristic, assuming he was kind and trustworthy and they went to help someone who would end up killing them. Researchers Petty & Cacioppo (1986); Petty et al., (2009) and Chaiken, et al., (1989) found that these two ways of thinking best fit into a dual-processing model. We either follow the deep/thoughtful path, which the researchers call the central route or systematic processing, or we follow the superficial/automatic path, which the researchers called the peripheral route or heuristic processing.

The central route to persuasion will be followed or systematic processing will occur when we carefully consider the message content. In order to follow this path or use this processing we need to be motivated and able to think about the message. What motivates us? It is not surprising that we are pushed to think more deeply when something is related to or about us, also called personal relevance (Petty, 1995). For example, when I was a senior in high school, we were told that they might change the school day from hour-long periods to block scheduling. They gave presentations to the students and we were all going to be able to vote and give our perspective on the possible change. All students, including the seniors who this would not impact, were going to vote. Since it wasn’t about me (not personally relevant), I didn’t follow the central route, but my younger sister who was a freshman and would be impacted did. Because it was personally relevant to her and going to directly impact her, she paid attention to the messages we were being given. She wanted to know how this would impact her day and if it would improve her learning. The only way she would vote in favor of this change was if the message was strong and demonstrated that this new structure was the best choice for learning. I, on the other hand, wasn’t going to be impacted by this change, so I did not waste my precious resources thinking about the message. We will see in a moment what my thinking did look like.

The other reason we will follow the central route of persuasion is if we are able to think about it. In order to be able to think about it, there needs to be limited distractions. We can’t be rushed or in a hurry, and we have to be able to understand the message being presented to us. It also helps if the message is repeated and written down (Petty, 1995). If a pharmaceutical company wants to persuade you to use their new drug, but their message is full of jargon and scientific information you can’t follow, then you aren’t likely to pay attention to the message or be persuaded to use the drug. So, in the example above, if the school board and employees pushing for the change want the students who find the issue personally relevant to get on board, they also need to give them time to process the message and they need to make sure that the message is something adolescents can understand. It would also help if they have an opportunity to see it more than once and can read the arguments at their pace. The situational determinants of being motivated and able are key to following the central route, but there is a dispositional determinant as well, the need for cognition (Haddock, et al., 2008). This concept deals with enjoyment from engaging in effortful cognitive activity. Individuals who score high on the need for cognition measure spend more time carefully processing the message, following the central route to persuasion (Cacioppo & Petty, 1982).

As noted earlier, it is adaptive for us to rely on heuristics and automatic processing of our world. It saves us time and our limited cognitive resources. For the majority of us, we mostly follow the peripheral route or heuristic processing (Petty, 1995). The context or situation that the message is delivered in is more important than the actual message. These context or situational cues trigger automatic responses and we quickly move forward in our lives. (Cialdini, 2008). Remember our example from earlier where my high school was proposing changes to our daily scheduling. I followed the peripheral route to persuasion. I am a busy senior who doesn’t really have the time to think about the message, and since it isn’t going to impact me, I really don’t care to spend time carefully evaluating the message. So, how can they persuade me to vote in favor of block scheduling? They need my automatic acceptance from situational cues. I would probably be persuaded by an authority or an expert on the topic, and if I am in a good mood, I will probably also go along with what is presented. In fact, this is what the school did. They brought in attractive and trustworthy experts, and they always had food and drinks during presentations. So, for those of us that weren’t personally impacted, we were likely to automatically be persuaded by those situational cues. More examples can be found in Robert Cialdini’s (2008) book, Influence: Science and Practice.

It is clear that we need to examine the persuasion situation more closely to understand exactly when our persuasive attempts will be most successful. Our motivations in persuasion will determine which path we want our audience to follow. If we want a more permanent attitude change, we will want the person or group we are attempting to persuade to follow the central route. If we just need them to go along right now or buy something once, then the peripheral route is a good choice. The next section will focus on the factors that lead to successful persuasion and how our processing route influences their effectiveness.

Figure 6.1. The Elaboration Likelihood Model

6.2. Factors that Lead to Successful Persuasion

Section Learning Objectives

- Explain what type of person is most persuasive

- Clarify what aspects of the message make it persuasive

6.2.1. Persuasive Communicators

The first factor that can impact the success of the persuasion attempt is the person communicating or the source of the persuasion. There are different ways that a source will be presented to us. They can be obvious — we see them. It could be a celebrity advertising a product on a television commercial or it could be an average American selling a new cooking tool in a social media ad. However, sometimes during a persuasive attempt, the source isn’t clear or obvious. They might be a narrator you can’t see or a print ad without any visible source of the persuasion (Petty & Wegener, 1998). What makes someone a persuasive communicator? Are there certain qualities that will make someone more or less persuasive to the audience? Research has found that credibility and attractiveness are important in successful persuasion.

6.2.1.1 Communicator/Source credibility. Let’s start with credibility. A review done by Pornpitakpan (2004) on studies from 1950-2004 found that using highly credible sources resulted in more persuasion. What makes someone credible? Perceived expertise and perceived trustworthiness are key to credibility. Perceived expertise is defined as someone we perceive to be both knowledgeable on a topic and has the ability to share accurate information with us (Petty & Wegener, 1998). In situations where we have low personal relevance or ability to process the message, it serves as a peripheral cue. Expertise will trigger us to automatically go along with the persuasive attempt because we believe that this person knows what they are talking about. Can you think of some examples? We often use heuristic processing while watching television. Let’s say you’re watching a toothpaste commercial. There is a dentist in a white lab coat discussing how effective a brand of toothpaste is. If you are persuaded in this instance, it is because of the cue of the dentist. You automatically think this is a good toothpaste because this expert told you it was.

Perceived trustworthiness is the other aspect of credibility we need to look at more closely. Research, not surprisingly, has found that when we do not feel like the person has anything to gain and that they are sincere, this is a strong indicator of persuasion. If people view someone as trustworthy, they will automatically be persuaded by the attempt. However, if the source is viewed as untrustworthy, even people who have a low need for cognition (don’t want to think deeply all the time) will engage in a similar amount of message analysis as individuals who are high in need for cognition (Cacioppo & Petty, 1982). Have you ever had the experience of shopping at a store where the employees are working on commission and only make money if they convince you to buy something? When I was growing up, I often shopped at a clothing store that used this model with their salespeople. When you went in, you were immediately approached and often they continued to interact with you while you shopped, hoping that you would buy something and they would get paid more. Their perceived trustworthiness dropped because it was in their best interest to persuade me to purchase something. So, when they told me that I looked great in that outfit, I was likely to be skeptical of their authenticity. I often avoided that store for that reason. Is there anything they could do to appear more trustworthy? It would benefit them to argue against their own self-interest. If they were to tell you that something you tried on wasn’t the right piece for you, that would actually make you more likely to be persuaded by them and buy the other clothes they recommended.

6.2.1.2 Communicator/Source attractiveness. Another characteristic that can help the persuasive attempts of a communicator is attractiveness. Attractiveness can include both physical attractiveness and likeability. As was mentioned earlier in the module, we hold a heuristic (mental shortcut) where we believe “what-is-beautiful-is-good”. Research has found that people associate talent, kindness, honesty and intelligence with beauty (Eagly, et al., 1991). These same studies have been done in a variety of contexts and individuals who are highly attractive are more likely to be voted for, hired for a job and granted leniency in the judicial system. When we aren’t motivated and able to think deeply, we follow the peripheral route and this is when peripheral cues like appearance can have the greatest impact on persuasion.

For Further Consideration

Can you think of ads or products that use really attractive communicators? For me, one example that comes to mind is the store Abercrombie and Fitch. Most of the time they have been in business, they have been known for their hiring practice of only employing physically attractive models who have a certain body type and sex appeal to sell their clothes. In 2015, they decided to change these discriminatory practices. It would be interesting to see if they are still as successful in selling clothes with their changes in advertising.

What are your favorite celebrities currently advertising? Is it perfume, their own clothing line or something unexpected? Do you notice that just their association with the product makes you like it more? Had you considered their impact on your feelings toward the product?

Another powerful aspect of attractiveness is likeability. One of the things that can increase liking is similarity. We like people who are like us (Byrne, 1971). This includes sharing opinions, personality traits, background, lifestyle and even when people mirror our behavior, posture, and facial expressions (Cialdini, 2008). A classic example of the power of similarity comes from a study done in the 1970s with clothing style. During this time period young people wore primarily two types of dress, what is referred to as “hippie” or “straight” fashion. The study had confederates wear one of these types of clothing and then approach people who were wearing one of the two types of clothing and ask for a dime to make a phone call. The results support the fact that similarity has the power to persuade. When the confederate’s clothing matched the person they asked, they were more likely to get a dime from them (Emswiller, Deaux, Willits, 1971).

6.2.2 Persuasive Messages

After assuring you have the appropriate communicator, the next step is to determine what types of message content will be the most effective. There are several questions we need to answer in order to completely understand the role of message content in persuasion. What is actually contained in the successful message? Is it full of logical arguments and evidence or is it presented to elicit certain feelings? Two emotions often used to persuade are pleasant feelings and fear. Another question we need to answer is: will the way the message is presented make it more or less persuasive? We will also have to decide how to present our perspective. Do we just present our side or do we present both our side and the other side? These answers will all be impacted by the audience’s processing route.

6.2.2.1. Solid arguments vs. emotion-based appeals. Let’s begin with an example. We are trying to persuade people to care about the amount of plastic impacting the environment and to change the way they think about plastic consumption. What kind of argument should we use? Should we present an argument filled with solid, logical, evidence including reasons for why we need to rethink plastic consumption, or would our audience be more likely to be persuaded by an emotional appeal where we scare them or make them feel sad about the impact of plastic on our planet? First let’s look at the research and then we will look at three news story links to see how information was presented to the audience.

We know that audiences who are motivated and able will follow the central route of persuasion. Remember, we are motivated to pay attention to the message when it is personally relevant to us. We also need to be able to process it. We need the time to think about it, and the message needs to be presented in a way that we can understand and really think about what is being said. If these conditions aren’t met, then we follow the peripheral route. We are going to respond based on peripheral cues, like credibility, attractiveness, etc. So, I am sure you predicted at this point that when someone is following the central route, they are going to be more persuaded by solid arguments. Those individuals who are following the peripheral route will be more persuaded by emotional appeals (Cacioppo, et al., 1983). We also need to consider if our audience is likely to have a larger number of individuals with a high need for cognition. This could impact the success of our persuasion attempt. We need to have more solid arguments if we have more of these individuals present.

Another important thing to consider is how the people originally formed their attitude. You might remember in Module 5 on attitudes, we discussed the different bases or components of an attitude: affect, cognition and behavior. We discussed that some people do not have all three bases for each attitude and that some attitude bases are stronger than others. This impacted our ability to predict their behavior with respect to that attitude. These findings address that. If your original attitude formation is more affective or emotion-based, then you will respond to persuasive attempts that are made with emotional appeals. However, if the origin of an attitude resulted in a stronger cognitive base, then not surprisingly, you will be more likely to be persuaded by a solid argument (Fabrigar & Petty, 1999). As you might imagine, it can be challenging to figure out what kind of audience you are dealing with. If they are mixed or you do not have the ability to determine which base is strongest, it might make the most sense to have an argument that contains both reason and emotion.

Alright, let’s return to our example. Here are links to three stories on plastic pollution.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3791860/

https://www.plasticpollutioncoalition.org/pft/2018/5/14/albatross

https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-40654915

The first story is a summary article from a respected peer-reviewed journal. I chose this because the messages here are solid, logic-based arguments on the impact of plastic. The second reading has an emotion-based focus. It is about the plight of the albatross and finding the dead birds’ stomachs filled with plastic that killed them. The final reading is from BBC news and it contains both appeals. Let’s think about the audiences who might consume these different presentations on the same issue. If you are reading a journal article, it is likely you have a high need for cognition and are following the central route. This second reading and similar blog posts about people’s experiences with this problem might drive you if you seek out emotional appeals about the topic. These individuals have a stronger affective base for plastic pollution. Finally, the last is a news source that might be read by both types of people. How can the writer reach them? To be effective, they will draw you in with emotional appeals, stories of individuals, animals and the landscape that are impacted negatively by this pollution. However, you will also see a large amount of information about the amount of plastic and other relevant arguments related to this problem. Both reason and emotion are needed.

6.2.2.2. Types of emotional appeals. There are different types of emotional appeals that we can make when trying to persuade people. Let’s start with evoking good feelings in our audience. When we make our audience feel good, we increase their positive thoughts and through association, we make a connection for them of good feelings and the message. When we are in a good mood, we are more likely to rely on the peripheral route. We don’t spend much time thinking about the message. We see that when people are unhappy, they spend more time ruminating or going over and over things. They aren’t persuaded by weak arguments (Petty, et al. 1993). When we watch cable television, we are afforded an opportunity to analyze these emotional appeals.

For Further Consideration

Can you think of some recent commercials you saw that attempted to make you feel good so they could sell their product to you? Ads selling soda are often good examples of this. For example, Coca-Cola had a campaign using the slogan “Open Happiness.” You will feel so good if you consume this product.

Another common emotional appeal is to elicit fear. Fear can be very effective most of the time. There are, however, a few situations when it will not work. Fear doesn’t work when you are trying to convince people to stop doing something that makes them feel good, like having sex or laying in the sun. It also doesn’t work when you use too much of it and don’t give the audience a solution to avoid their fear. In that case, it is easier for the audience to deny and continue the behavior. Humor and fear combined have also been found to be more persuasive (Mukherjee & Dube, 2012). A great example of something that fear alone isn’t effective at persuading but in combination with humor is very persuasive is sex and condom use. The fear appeals would want you to think of having your life stolen from you with unwanted pregnancies and potentially losing your life from HIV/AIDS or the discomfort of sexually transmitted diseases. The addition of humor can be seen in Trojan condom ads. These ads are generally funny and they combat the fear of negative things that come from something we see as pleasurable, or sex.

6.2.2.3. The way the message is presented. The message can be presented in different ways and these strategies can impact how persuasive the message ends up being. There are several strategies that work most effectively when you are processing things heuristically or peripherally, which we know happens quite frequently. We can start by looking at foot-in-the-door phenomenon. The terminology for this comes from the idea of door-to-door salespeople. If they can get into your home, they feel confident in making the sale. What does this strategy entail? The communicator will first make a small request. Once you agree to the small request the communicator will ask for something larger. Remember, this person’s goal is the larger request, but in order for you to agree to it, they are using a strategy that plays on our need to be consistent. Once we have made a commitment, we will feel pressure to remain consistent and avoid the unpleasant feeling of hypocrisy. One of my favorite studies demonstrating this involves having people agree to sign a petition that driver safety is important. Then two weeks later, they ask for the larger request. All told, 76% agreed to place a billboard in their yard. Yes, you read that correctly: a BILLBOARD (Freedman & Fraser, 1966). Our need to be consistent and not be viewed as hypocrites is powerful.

Another technique, a variation of the foot-in-the-door technique is called lowballing. Lowballing is a fascinating strategy. The communicator will put forward an attractive offer, one that is hard to say no to. Once the offer is agreed to, you will come up with new reasons for why you are glad you made the commitment to this offer. This is where it gets interesting. The original offer is removed. The whole reason you went along with it was because of that desirable offer and now it is gone. What should we expect – are we upset, do we change our mind about what we have agreed to because it isn’t as good as the original offer? No, we don’t. We go along with it and are happy about it. Cialdini (2008) discusses this in his book Influence: Science and Practice. The examples he gives are great. The first one is a traditional sales situation. How many of you have bought a car from a dealership? Did you agree to a price with the salesperson and then they leave you to make sure that their manager agrees to it? This is where the lowball begins. You agreed to the attractive offer from the salesperson. They will sell you the car for the price you want. While they are gone, you are coming up with all these new reasons for why you made this decision. The car has great mileage, horsepower, sunroof, tinted windows, a backup camera and great sound system. When the salesperson comes back and removes this original offer (which is why you agreed in the first place), you still take the car and you are happy about it. This technique is regularly used in car sales. Another great example occurred with one of Cialdini’s friends, Sarah. She had been dating Tim for a while, and she wanted to get married. Tim wasn’t interested in marriage. Sarah ended the relationship, met someone else and was engaged to be married. Tim comes back into the picture and offers Sarah a great deal. He will marry her if she comes back to him. She leaves her current engagement and returns to Tim. She comes up with all these new reasons for why Tim is the right guy for her. Then Tim lowballs her, removes his original offer of marriage and Sarah happily stays with him. She has all these new reasons for being with him, so when he takes away one (even though it was the initial reason for her taking him back), it doesn’t matter because it is just one reason. She is committed to him, happy and not married.

The last technique we will discuss is called door-in-the-face. I know that two of these strategies have the word door in them and this can seem tricky when you are taking a test over the material, but a good way to remember the difference is to actually think about what the phrase says. With foot-in-the-door you can picture a small part of your body getting in and then once that small part is in the door, the rest of you is not far behind. Small to large. With door-in-the-face, something large is presented and the metaphorical door is slammed in your face because the request is too big. Then you knock and offer a smaller request, which is usually accepted. The smaller request is what you really are trying to get. The two processes that are working to make this technique effective are reciprocity and perceptual contrast. Reciprocity is another peripheral cue. When someone does something for us, we feel indebted to them and want to immediately return to equity in our relationship. This makes sense — survival would have depended on successful relationships and sharing resources. If you were known as a taker or moocher then this would have negatively impacted your relationships. We still see this in our relationships today even though survival might not be at the core of them. So, with door-in-the-face, when your initial offer is denied and you come back with a smaller one, the other person feels like you gave in or gave them something with the compromise you are attempting to make. They then are more likely to accept that second smaller offer because they feel indebted to your compromise.

The second reason you went along was perceptual contrast. This cue deals with the change in perception related to how things are presented. So, in the door-in-the-face situation, we are presented with something large and then something small. The second presentation of the smaller item after the large item changes our perception and we now see it as smaller than if we had just been presented with the small item alone. Let’s look at a few examples. First, I want you to clean the whole house. You don’t want to. Okay, how about you just clean your room? Well, based on what we just learned, this should drastically increase the likelihood that you will clean your room than if I had originally just asked you to clean your room. First, you want to reciprocate my compromise, and second, your room seems much smaller after being compared to the WHOLE house. This will be a great tool for persuading roommates, spouses, or children to do the small things you want (just clean your room).

For Your Consideration

Can you think of something large that you want? What would be a way of using foot-in-the-door to get it? Can you think of a time foot-in-the-door was used on you? Have you ever experienced lowballing or used it one someone else? What was the situation? What was the initial attractive offer and what other reasons kept you from changing your mind when the initial offer was removed? What was your initial offer you used and then took away? Finally, think of an example of door-in-the-face? Were you the persuader or the person being persuaded? What was the situation?

6.2.2.4. One-sided or two-sided appeals. The last common question about message content has to do with whether you can be more successful with just presenting your side of the argument or if you need to present both sides to be effective. Again, it really depends. One-sided appeals work best when the audience agrees with you. A one-sided appeal can be the wrong choice if the audience processes through the central route. It will motivate them to seek out the other side and could result in trust issues. Which if you remember from earlier in this section, if you are not seen as a trustworthy source, that can really damage your effectiveness. The two-sided appeal is most effective and enduring when the audience disagrees with you. It can be useful right from the start to address the opposing side and then present your argument. If you watch television with courtroom scenes you often see this technique. The prosecutor or defense attorney will start with “my opposition is going to tell you X, but I want you to see it this way”. When they don’t do this, you are going to spend more time thinking of the opposing arguments while they are talking rather than listening to their case.

An illustrative example comes from a study done at a university encouraging recycling. They placed signs on the trash cans that said “No Aluminum Cans Please!!! Use Recycler Located on First Floor Near Entrance.” Underneath that sign was a smaller one that said, “It may be inconvenient, but it is important.” After adding the second sign, which turned the one-sided appeal into a two-sided appeal, 80% recycled compared to 40% before it was added (Werner, et al., 2002).

For Your Consideration

Return to our example of plastic pollution from the beginning of the section. How do the different types of readings present the message? Are they one-sided or two-sided? Plastic obviously serves us well in a lot of situations. In fact, it may be impossible to completely avoid it. So, who is the audience? If you are reading a blog or an emotionally geared piece, then it is quite likely that they are only using a one-sided appeal. However, if part of your audience might disagree or have a high need for cognition, you should use the two-sided appeal.

6.3. A Closer Look at Cults: Dangers and Resistance to Persuasion

Section Learning Objectives

- Exemplify what a cult is

- Examine the persuasion processes used against us

- Clarify ways to resist these attempts at persuasion

We should start by acknowledging that persuasion can be good, neutral or bad (which we will look at more closely with our cult examples). We can persuade people to stop bad habits, vote for someone who can positively change our world, think more about their plastic consumption, clean their rooms, and/or marry you. The focus of this section is on the dangers, which we see when people attempt to take advantage of our tendency to automatically respond to peripheral cues or triggers as we save our cognitive resources. Salespeople, con artists, politicians, and crappy relationship partners, are a variety of people who can use our natural tendencies against us. This section will focus on the danger of cults. There are two we will look at and the persuasion techniques that were utilized. We will then look at some suggestions for fighting against our automatic tendencies.

6.3.1. Two Examples of Cults

The first example of a cult is from the late 1950s and is not a well-known cult. In fact, I couldn’t find anything about it through casual searches without its connection to the psychological researchers who studied it. Festinger, who you might remember for his work with cognitive dissonance, was interested in how doomsday cult members could continue on with the group after the predicted end didn’t arrive. A great resource that covers this is the original source — a book written by Festinger, Riecken, & Schacter and published in 1964 about their experience participating in this very small doomsday cult in Chicago. They called themselves the Seekers and were originally smaller than 30 members. They were led by two middle-aged individuals and the study gave them alias names to protect their identities. The male was named Dr. Armstrong and he was a physician at the college. The female, and person receiving the messages from the aliens called Guardians, was given the name Mrs. Keech. She predicted that an end of the world event would occur before dawn on Dec. 21, 1954 and the true believers would be picked up at dawn by the Guardians (aliens). This alone is interesting, but the more interesting part is that three psychologists gave us an inside view of exactly what happened from the announcement of the “end” and then through the weeks leading up to the event and the night of the so-called “end”. As reported by the psychologists who were present, when the aliens didn’t pick them up, everyone sat in silence, visibly upset. They sat together waiting for the time of the flood and the end of the world. This time also came and went without incident. Mrs. Keech immediately afterward received a new message from the Guardians saying that all of their light and faith had prevented the tragic event. One person got up and left, disgusted by this — that was it. Mrs. Keech then received another message that they needed to contact the media and anyone who would listen. They needed to get the word out about their group and recruit members. Everyone left and started following the message. What is interesting about this approach is that prior to the failed end of the world event, they were extremely secretive and reluctant to add new members. However, at least that night and for a while after, the members of this group increased their commitment to the cult. Today we know Mrs. Keech’s actual name was Dorothy Martin, a housewife from Chicago. The group in Chicago didn’t remain and after being threatened with commitment to a mental facility, she moved to Peru where she continued to receive messages and changed her name to Sister Thedra, starting the Association of Sananda. This organization continued until 1992 when she died.

For more on this group, please visit: https://www.encyclopedia.com/science/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/association-sananda-and-sanat-kumara

What kind of persuasion principles were employed in this situation? We see prior to the doomsday event that members made drastic decisions; they quit jobs, sold houses, and cut ties with family/friends who didn’t understand. They needed to remain consistent with these choices, and their commitment to the cult was very high. When the event passed and nothing happened, they used social proof — our heuristic that if others are doing it, it must be correct — through the recruitment of new members and the publicizing of their group to help them stay committed to the group. In the end, most people left the group, but this isn’t the case for most cults.

The second example is Jonestown and cult leader Jim Jones. Jim Jones started as simply a pastor of what seemed like an all-inclusive church in Indiana in 1955. In a time of segregation and ostracism of those that were different, Jim created a utopian environment where all were accepted. It was a place where those without family could find family and those who sought a place of equality for all could find it. He moved the church to California in 1965, fearing nuclear war. It was from this point that the church (now called the People’s Temple) started traveling down a more sinister path. Most members started by just attending once a week and then committing to more nights a week. They would encourage their friends and family to join. They gave a small amount of money to the church, and that slowly increased until they gave their whole paycheck. When they moved to California, they lived and worked on the church property, which means they sold their houses and cut ties with family who didn’t support the church. Jones also encouraged the children to be adopted by others in the church and for spouses to have sex with other members of church, especially Jim. He aimed to break their bonds within the church and outside of the church. They eventually moved to the jungle of Guyana as an attempt on Jim’s part to protect his people and church. He believed they were under attack from everyone. After a visit from a Congressmen, who was worried people were being held against their will, was shot and killed at Jim’s request, Jim forced everyone at gunpoint to drink poisoned Kool-Aid. A few who escaped into the jungle and a few from the Congressman’s group who lived, helped us to better understand what happened (Nelson, et al., 2007). This cult and the subsequent deaths are so fascinating, there are many documentaries and stories written about what happened. People often think how could this happen? Why didn’t they leave? How could they let someone do these things to them? People think that they would never allow these things to happen to them.

Let’s look at the persuasion techniques that were used and how people automatically responded to them. They had no idea that they were being persuaded to someday voluntarily kill themselves. If you look, foot-in-the-door (which we discussed earlier) is running rampant, as well as lowballing. Jim had them commit to many small requests and over time slowly increased his requests. He did this with church attendance and church work, money donated to the church, giving up custody of their children and then breaking their marital bonds. Eventually, large requests like moving to another state and then another country were easy to make because they had already committed to so much. In order to remain consistent, they had to make these larger commitments as well. They had given everything up for this church’s mission. Jim used emotional appeals to initially get certain kinds of members; those who were ostracized or didn’t have anyone such as the homeless. He would perform miracles for these individuals. The members who were doctors, lawyers and more likely to follow the central route were recruited with strong social and political messages. He provided a utopia where everyone was equal and where the elderly were given medicine and taken care of. He recruited with attractiveness and liking. He made himself credible — a trustworthy expert. It wasn’t until later that people saw a different side to Jim. It’s clear that these individuals committed to something that later didn’t look anything like the initial offer.

6.3.2. Resisting the Temptations of a Cult

How can we resist the dangers of situations like this? Cialdini (2008) offers some great tips to avoid the main techniques that are used. We will focus here on how to fight commitment and consistency’s powerful pull. He suggests two ways to combat it. Listen to your stomach and your heart. He says that consistency is often important and good for us in our lives. However, it isn’t always, as seen above with the cults. When you feel trapped by your commitment to a request, you often feel a tightening and discomfort in your stomach. He suggests that in this instance, the best way to combat that feeling is to bring this attempt to the persuader’s attention. “I am not going to go along with your request because it would be foolish to just remain consistent when I don’t want to go along.” He says we can’t always feel our stomach signs, so ask in our heart of hearts ‘does it feel right?’ Ask yourself if you could go back to beginning with the information you know now, would you make the same choices? If no, then the pressure of consistency should lessen and you can say no.

Module Recap

Persuasion is a complex topic, but hopefully you made it out with a much greater understanding of how you process information and persuasion attempts, either centrally or peripherally. You now know what types of communicators and messages are most effective in different contexts and with different audiences. Finally, you are more aware of the dangers of being taken advantage of by individuals who are aware of our frequent automatic responses to peripheral cues. The next module will continue our journey through social influence by examining conformity more closely.

2nd edition