Module 5: Attitudes

Module Overview

An important part of how we think about ourselves and others comes from our knowledge of how we view the world. This view, as we have seen from previous modules, is shaped by our self-knowledge and the ways we think and perceive, which we saw are often filled with errors and biases. In this module, we are turn our attention to our attitudes. They are the final piece to understanding how we think about ourselves and others. This module will focus on what they are, why they are important – focusing on the predictive nature of attitudes and finally how our behavior can impact our attitudes.

Module Outline

- 5.1. What is an Attitude?

- 5.2. Why are Attitudes Important?

- 5.3. How does our Behavior Impact our Attitudes?

Module Learning Outcomes

- Describe an attitude.

- Explain why attitudes are important.

- Introduce behavior prediction models.

- Explain how our behavior impacts our attitudes.

5.1. What is an Attitude?

Section Learning Objectives

- Define an attitude

- Examine the structure and function of an attitude

- Investigate the origins of attitudes

First, an attitude is our assessment of ourselves, other people, ideas, and objects in our world (Petty et al., 1997) Ask yourself, what do you think about Jenny in your social psychology course, your discussion board question that is due this week, or puppies and ice cream? Your responses to these questions are your attitudes toward them. You might respond with “Jenny is really nice and always helps her classmates” or “I hated the discussion board question because it was really boring”. For most people, their attitude responses toward puppies and ice cream would be positive. We will see in this section that attitudes are a bit more complex than these examples suggest.

5.1.1. Structure and Function of an Attitude

The first way we can examine attitudes is through a “tripartite” model. It is often referred to as the ABC’s of attitudes and consists of three bases or components, affect, behavior, and cognition. Originally, researchers believed that everyone’s attitudes contained all three bases, but we now know that some attitudes do not contain all three, and some are even inconsistent with each other (Rosenberg et al., 1960; Miller & Tesser, 1986b). Let’s more closely examine what this means. When we express affect, we are sharing our feelings or emotions about the person, idea, or object. In the examples above, when we love or hate those are clearly our feelings about the attitude object. We can see the cognitive component as well. This involves our thoughts about the attitude object, they often look like opinions or facts that we hold. So, when we think Jenny is nice and always helps her classmates or the discussion board question is boring, these are the facts as we see it about the attitude object. The examples above do not contain a behavioral component. This would be actions that result from these thoughts and/or feelings. So, we could add that you might befriend Jenny, not put as much effort into your discussion board response, buy ice cream, and pet puppies.

Figure 5.1. Tripartite Model of Attitudes

For Further Consideration

Take a minute and think of some attitudes you hold. Write them down on a sheet of paper. You can use them throughout the module. Let’s start with the first couple you wrote down. Try to break them down into the ABC’s of attitudes. Start with affect (what are your feelings about the attitude you hold), cognition (thoughts about the attitude you hold), and behavior (actions you take because of the attitude).

In the above examples and the ones you practiced, you were assuming that the attitude contained all three bases. Again, we know that some attitudes are only made of one or two bases and we also know that they can be inconsistent (Millar & Tesser, 1992). An example might help us to understand – you might only have thoughts and feelings about puppies. You don’t have any actions connected to it. These thoughts and feelings might not line up. You might love puppies, but your thoughts are connected to how allergic you are to them and how much hair they shed, which will make your allergies worse. So, this can be a challenge for us later when we are trying to predict how you will behave around puppies. You love them, but you cannot be around them since they make you sick. Will you pet the puppy anyway? Will your affect base be stronger than your cognitive base? We need to know which one is more important, stronger or more powerful to predict your behavior (Rosenberg et al., 1960; Millar & Tesser, 1986b).

Functional theorists Katz (2008) and Smith, Bruner, & White (1956) addressed the issue of not knowing which base (affective, cognition or behavior) was most important by looking at how the person’s attitude serves them psychologically. They came up with four different functions that an attitude might serve. One of the most beneficial things an attitude can do for us is to make our lives more efficient. We do not have to evaluate and process each thing we come into contact with to know if it is good (safe) or bad (threatening; Petty, 1995). This is called the knowledge function, and it allows us to understand and make sense of the world. My attitude towards insects is somewhat negative. I tend to have large reactions to bites from them and although most do not bite, my immediate reaction is to avoid them if at all possible. In this way my attitude keeps me from having to evaluate every type of insect I come into contact with. Saving time and allowing me to think of other things in life (Bargh, et al.,1992). This example might have prompted you to think that this generalization could lead to discrimination, and you would be correct. In an attempt to be more efficient, I am not stopping and processing every insect I come into contact with and some insects are good (safe). We will discuss how this helps explain prejudice and discrimination in a later module.

The other three functions serve specific psychological needs on top of providing us with knowledge that allows us to make sense of our world. Our attitudes can serve an ego-defensive function which is to help us cover up things that we do not like about ourselves or help us to feel better about ourselves. You might think cheerleaders are stupid or superficial to protect yourself from feeling badly that you aren’t a cheerleader. Here you defended against a threatening truth – you aren’t a cheerleader, which you want to be, and you boosted your self-image by believing that you are better than them – you are smart and complex. We can categorize some of our attitudes as tools that lead us to greater rewards or help us to avoid punishments. So, women might have developed an attitude that having sex with many partners is bad. This has both a knowledge function and a utilitarian function by helping women avoid the societal punishment of being called a slut and then seeking the reward of being the kind of girl that someone would take home and introduce to their parents. The final function centers around the idea that some of our attitudes help us express who we are to other people, value-expressive function. We see this a lot on social media. If you were to examine someone’s Facebook or Instagram page you would see that their posts are full of their attitudes about life and they intentionally post certain things so that people will know who they are as a person. You might post a lot of political things and people might see you as a politically engaged person, you might post a lot about the environment and people see that you are passionate about this topic. This is who you are.

For Further Consideration

Look at the attitudes you listed earlier. Can you identify what function they serve in your life? Most attitudes serve the knowledge function, but are they also serving the ego-defensive or the utilitarian or the value-expressive functions? Pick out an example for each one. Do you have social media? What does it say about who you are? How does it meet the value-expressive function of attitudes?

Understanding the structure and function of attitudes can be useful for us but it is also important to know how they form or why some seem to be more powerful in guiding our behavior. Often, attitudes are formed from our own unique life experiences. This is why you will find that people’s attitudes and the strength of those attitudes vary so widely. As students in this course you will often find people have strong attitudes about certain topics. You might be surprised when they hold an attitude that is so different from yours and wonder how that is possible. We all have unique experiences that will shape our attitudes, opinions, and ideas about the world. So, when someone expresses an attitude that is different from your own it is most likely they had an experience in their own life that shaped that attitude (Fazio & Zanna, 1978). It is also possible to form an attitude indirectly from other’s experiences. For example, children develop many of their initial attitudes by observing caregivers and sibling’s reactions to their world. If your Mom or Dad is afraid of spiders or insects, then often children will develop an attitude of dislike and fear. Research finds that when attitudes are formed from direct experiences in life, as with the above example of being bitten by a spider and having a bad reaction, rather than indirectly where your parents are scared of spiders, there is a stronger attitude and a resulting stronger connection to someone’s behavior. What this means is we will be able to better predict your behavior toward a spider with direct experience formation over indirect experience formation.

Why do you think that attitudes formed from direct experience have greater predictive power on behavior? Well, recall what you learned in the module on the self. You might remember our discussion of the self-reference effect. We know that anything that is connected to us will be easier to remember and come to mind more quickly. So, it makes sense that if it happened directly to us it comes to mind quicker than attitudes that come from things that we heard about or saw someone else experience. If we follow this line of thinking, then indirect attitudes that came from people connected to us vs. strangers we read about online, should be stronger. The associations that are closest to us will result in the strongest attitude formation. (Anderson, 1993).

5.2. Why Are Attitudes Important?

Section Learning Objectives

- Explore how attitudes influence social thought.

- Examine factors that influence an attitude’s predictability of corresponding behavior.

5.2.1. Attitudes Influence Social Thought

We research value attitudes because we believe that they strongly influence social thought and can predict what someone will do. We as humans like for our worlds to be predictable. We want to believe that knowing how someone thinks and feels about something will give us insight into how they process the information they take in, as well as what they do with it. We have seen with previous modules how the way we think influences behavior, and we know attitudes color how we perceive all the information that is funneled in our direction.

In the previous module we focused on how our beliefs can alter our behavior and other people’s behavior. For example, with the self-fulfilling prophecy, our judgment of another person can alter our behavior towards them, thereby influencing them to respond to our behavior by acting in a way that supports our initial judgment and fulfills their prophecy. Our attitudes are often used to guide our behavior (Bargh, et al.,1992).

5.2.2. Attitudes Can Be Predictive of Behavior

Let’s start with an example. Do you think it is important to be honest? Most people say yes. They do not want to be perceived as a liar. We need to be trusted in order to have successful interactions and relationships. Your strong attitude toward honesty should allow me to predict that you will tell the truth. Would I be accurate in my prediction? The answer is no. Some of you might already be thinking of situations when the most socially acceptable response is to lie. What if you are at a wedding and the bride asks you how the cake tastes? It tastes terrible. Will you tell her the truth? The norms (unwritten rules or expectations) of this situation are to make sure the bride has a great day, so most of us would lie to protect her feelings. This illustrates a great example of an attitude not being predictive of someone’s behavior. Let’s examine when and how someone’s attitude might be more or less predictive of their behavior.

5.2.2.1. Aspects of the situation – Situational constraints. Let’s first look at the situation. Like in our honesty example, it seems that there are some moments where our attitude cannot be expressed in our behavior. When there are situational constraints that come from social norms, or unwritten rules that guide our behavior, we find that people might not behave according to their true attitude. You might have an attitude that dressing comfortably is more important than how you look. There are a lot of situations that might keep you from expressing this attitude. Often, we have to wear certain types of clothes to work, church or other events.

5.2.2.2. Aspects of the situation – Time pressure. Time pressure is another aspect of the situation that impacts how predictive an attitude will be. In this case, it will strengthen the attitude-behavior connection. We know that under time pressure, when we are in a hurry, we use attitudes as a way to save on our cognitive resources. We do not have to process the situation which takes time. We can just use the shortcut of our attitudes. In this way attitudes are operating much like heuristics which you learned about in the last module. They allow us to act with very little thought. This is why in this situation, our attitudes will vary and likely result in a behavior that fits our attitude.

5.2.2.3. Aspects of the Attitude – Attitude strength. It isn’t just the situation that can impact the attitude-behavior connection. There are also aspects of the attitude itself that can strengthen the connection. The stronger the attitude the more likely we can predict someone’s behavior from their attitude. A strong attitude is one that has the power to impact our thoughts and behavior and is resistant to change and stable over time. The research on strong attitudes often finds quite a few strength-related attitude attributes. We are going to focus on a few of them: attitude importance, knowledge, accessibility, and intensity (Petty & Krosnick, 1995).

We have already learned that an attitude will be stronger when it comes from our direct experiences and if we are closer to these strength-related attitude attributes, we can see how they contribute to attitude strength. Strong attitudes are important to us or psychologically significant and the more important an attitude is, the stronger it will be (Petty & Krosnick, 1995). So, you can ask yourself questions like, “How personally affected am I by this attitude object? How much do I care about it?”. Can you think of something that means a lot to you? I care a lot about the issues that impact women. I grew up in a highly gender stereotyped household and that direct experience impacted me and made it important to me. I now feel strongly about equality between the genders.

As we learn more about our attitude it will grow stronger. Knowledge of that attitude is the second factor. This is all the information we have about the attitude object (Petty & Krosnick, 1995). To continue the example, I spend a lot of time reading books on feminism, study gender equality, teach about gender and become more knowledgeable about equality.

If you remember from Module 3, the self-reference effect indicates that something connected to us will be remembered easier and more quickly. This is important to the third factor that increases strength, accessibility. We know an attitude is strong when it comes to our mind more often and more quickly (Petty & Krosnick, 1995). We measure this by timing how long it takes you to think about an attitude in relation to an attitude object.

Most people have a strong reaction to the following picture:

This strong reaction is a good example of attitude intensity or the strength of the emotional reaction that is elicited from the attitude object. In this case, maggots tend to elicit a strong reaction of disgust. Strong attitudes aren’t just better at predicting behavior. They are also less likely to change over time. This will be important to us in the next module on persuasion.

5.2.2.4. Aspects of the attitude – Attitude specificity. Another way that we can increase the chances that an attitude will lead to a consistent behavior is to make sure that the attitude is more specific than general. For example, if I want to predict if you will attend church every Sunday (more specific), I can’t ask you how you feel about religion (more general). I need to ask your attitude about attending church every Sunday. You will notice that they are at the same level of specificity or are more specific than general. Typically, the more specific the attitude the better it will be at predicting the specific behavior.

For Further Consideration

If you wanted to know if people were planning to vote for a specific candidate in the current election, what attitude would you need to know about them to predict who they would vote for?

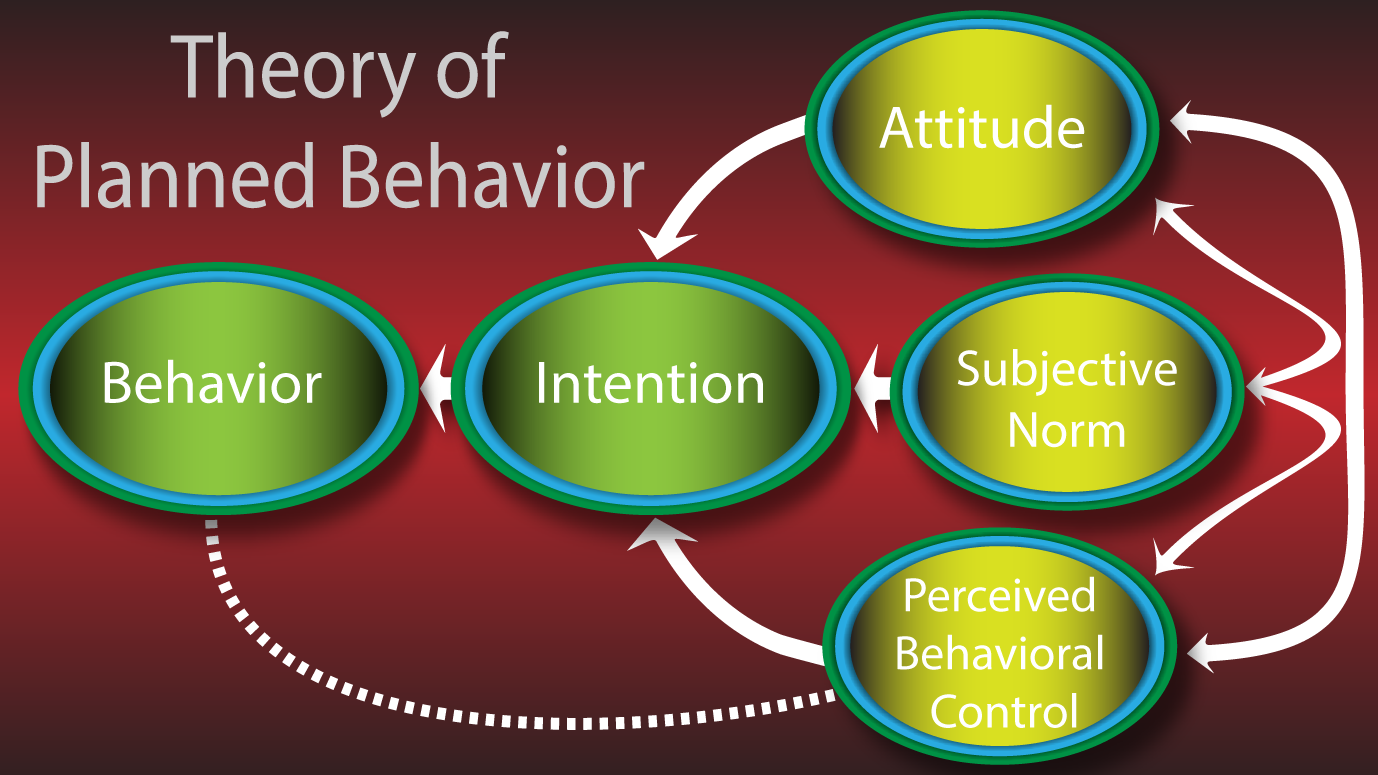

5.2.2.5. Behavior prediction models. The important distinction between general attitudes and behavior-specific ones is that behavior-specific ones allow us to better predict behavior. Fishbein and Ajzen (1975) introduced a model that would allow us, through someone’s evaluation of behavior (attitudes) and thoughts on whether other important people would do the behavior (subjective norms), to predict their intention to do behavior and then that intention would predict whether they actually end up making the behavior. For example, one study looked at whether people would cheat on their significant other (Drake & McCabe, 2000). First, we need to know their evaluation, positive or negative, toward cheating on their significant other. Then we need to know if important others in their life would cheat on their significant other. Both pieces of information determine their intention to cheat on a significant other. If they intend to cheat then we will expect to see when we look at their behavior that they will cheat on their significant other. This is the theory of reasoned action. Later Ajzen separated from Fishbein believing that another critical component was part of the model and missing from the original theory. This model became the theory of planned behavior and added perceived behavioral control (Ajzen, 2012). This component is much like self-efficacy discussed in a previous module and deals with your confidence in being able to engage in the behavior. So, if you look at our cheating example, Ajzen believed that you could meet all the conditions above intending to cheat, but still not cheat. He said that if you do not believe you can cheat because you do not have the opportunity (place to cheat, person to cheat with, do not think you can get away with it) that you will not cheat. This an example of perceived behavioral control.

Figure 5.2 Theory of Planned Behavior

5.3. How Does our Behavior Impact our Attitudes?

Section Learning Objectives

- Define self-perception theory.

- Define cognitive dissonance.

5.3.1. Our Behavior Can Make Us Aware of Our Attitudes

One way that our behavior impacts our attitudes is when it helps us to understand what we are feeling. Often throughout the day we will have moments of uncertainty or ambiguity about our evaluation of an object, person, or issue. We will look to our actions to determine what it is we are feeling, called self-perception theory. All of this happens outside of our awareness. It is only through discussing it in a psychology course that you might introspectively examine the process and realize that an uncertainty about your feelings or attitude about your favorite music can be cleared up by looking at your music library and realizing that both rap and alternative are equally your favorite. Most often though we are not actively engaged in introspection and this process occurs outside of our awareness through an automatic processing of facial expressions, body posture, and behaviors (Laird & Bresler, 1992).

One of my favorite studies in psychology because of the ingenious methodology helps exemplify this idea. Researchers had one group of participants place a pen in their lips, which would inhibit a smile, and another group of participants were asked to put a pen in their teeth, which would facilitate a smile. Both groups then watched a funny segment of a cartoon. The researchers predicted and found that participants in the teeth condition evaluated the cartoon as funnier than the participants who placed the pen in their lips. The thinking behind this is that a pen in your teeth makes the muscles around your mouth move into a smile and we should interpret our feelings as positive based on this facial expression (Strack, et al, 1988). In recent years, researchers have done variations of this experiment with rubber bands and other interesting methodologies and found similar results (Mori & Mori, 2009).

5.3.2 Our Behavior Can Conflict with our Attitudes

Sometimes as we move through our lives, we will realize that some behaviors we are engaging in do not fit with one of our attitudes or we will have two attitudes that we realize seem to contradict each other. This inconsistency or conflict results in an unpleasant feeling that we want to immediately get rid of or reduce, called cognitive dissonance. It is another instance of how a behavior impacts our attitudes and, in this case, could change it. An example of this would be if you toss a can or newspaper in the trash and you hold the attitude that recycling is important to saving the planet. You will probably immediately feel like you are a hypocrite, especially if someone else points it out. It is important to us to get rid of this feeling as quickly as possible.

We will do this in one of three ways and choose the one that requires the least effort. We can change our attitude or behavior. I can take the can out of the trash. This is probably the option that requires the least effort. The next option for reducing dissonance is to seek out new information that supports our attitude or behavior. A popular example here is that smokers who feel dissonance from their behavior and the research on smoking dangers will seek out information that this research is inconclusive or minimal. In our example, we might recall a recent article we read outlining the recycling of one person and showing that it does not change the overall picture of climate change. We leave the can and reduce our dissonance. The last option is called trivialization. This is where we make the attitude less important. We might decide that recycling isn’t as important to us and that it isn’t changing the world. However, something like reducing our plastic consumption is an important attitude to replace the dissonant one (Petty, 1995).

Can you think of the last time you felt this unpleasant feeling from conflicting attitudes or an attitude and behavior? This process often occurs outside of our awareness. It is again only in a psychology course and through the introspection process where we would consider situations with these inconsistencies and then try to remember how we reduced them. A popular classroom demonstration to help students experience cognitive dissonance has students report how they feel about things like helping the homeless, eating a certain number of fruits and vegetables, voting in elections, and exercising regularly. As you can imagine most people have favorable attitudes toward these behaviors. They are then asked whether they have engaged in these activities recently or in the last year. Most answer no and experience cognitive dissonance. Can you imagine yourself in this situation? Which reduction technique would you use? I imagine that for most students the easiest one is trivialization and they might say, ‘This is just a dumb activity that teacher is doing.’ However it is possible that some students went on to exercise more or volunteer at the homeless shelter or sought out information that you can still be healthy, a good person, or civically engaged without doing those four types of behaviors.

Module Recap

This module covered attitudes, what they are, their structure and function, where they come from, their importance in their predictive nature, and how our behavior can influence them. Our evaluations of the world around us play a powerful role in shaping our world and guiding us through it. It isn’t surprising that attitudes are one of the most popular topics in social psychology. We ended this module by talking about cognitive dissonance and found that it has the potential to lead to attitude change. As we move into the next part of the text on influence, we will start with a module on persuasion. This module will build on our knowledge of attitudes and exemplify how persuasive communication can also lead to attitude change.

2nd edition