Module 4: The Perception of Others

Module Overview

In Module 4 we continue our discussion of perception but move from how the self is perceived and constructed in the mind to a discussion of how others are. We will frame our discussion around social cognition theory and the process of collecting and assessing information about others. To really understand this process, we have to first understand how communication occurs in the nervous system. Then we will discuss what information we obtain, factors on how this information is obtained, the meaning we assign to the information we collect in terms of categories and schemas, how accurate these schemas are, and finally the judgments we form. From this we will tackle the issue of how we determine the cause of a person’s behavior, called attribution theory. We will discuss dispositional and situational attributions and then two theories explaining attribution. We will conclude by describing types of cognitive errors we make when explaining behavior.

Module Outline

Module Learning Outcomes

- Identify typical pieces of information we obtain about others to form judgements about them.

- Clarify how accurate our schemas and judgments of others are.

- Clarify how attribution theory explains the reason why a behavior was made.

4.1. Person Perception

Section Learning Objectives

- Define person or social perception.

- Outline how communication in the nervous system occurs.

- Identify the parts of the nervous system.

- Define social cognition and show how it relates to the communication model.

- Outline and describe the types of information we collect from others.

- Differentiate the negativity effect and the positivity bias.

- Clarify what the halo effect is.

- Define perceptual set.

- Explain how deception is used in revealing who we are.

- Outline how we assign meaning when we assess.

- Differentiate and exemplify the three types of schemas.

- Contrast group stereotypes, prototypes, and exemplars.

- Describe the benefits of schemas.

- Clarify how accurate our schemas are, defining key terms.

- Identify the connection between schemas and memory.

- Identify the connection between schemas and behavior.

- List and describe heuristics we use in relation to schemas.

- Identify factors on our judgments.

- Explain what priming, framing, affective forecasting, and the overconfidence phenomenon are.

4.1.1. Elementary Social Neuroscience

To begin our discussion of how we perceive others we will sort of take a step back and discuss communication in the nervous system. Why is that? When we use the term person perception or social perception, as it is also known, we are discussing how we go about learning about people, whether significant others, family, close friends, co-workers, or strangers on the street. This process begins by first detecting them in our environment. How so?

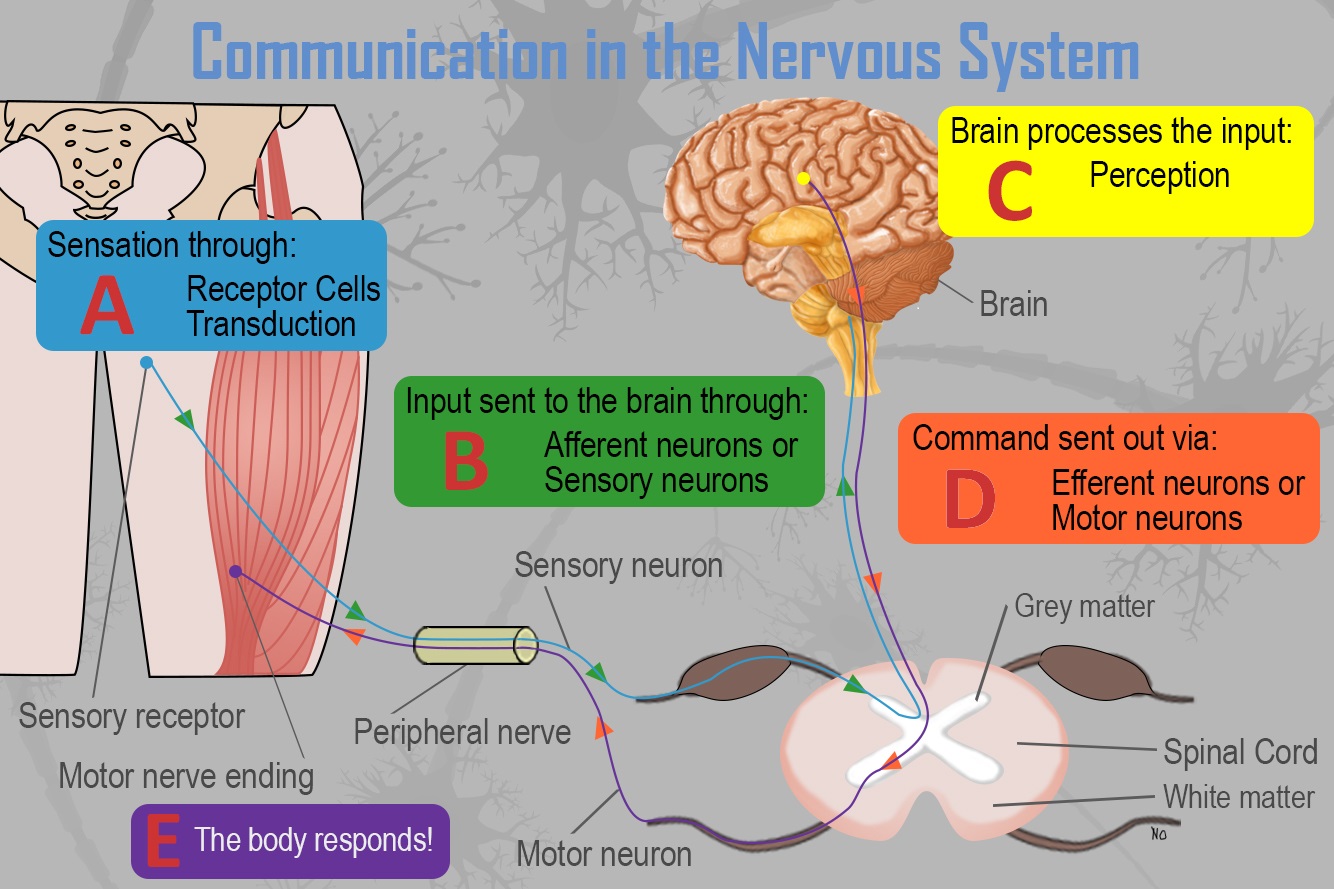

4.1.1.1. Communication in the nervous system. Figure 4.1 gives us an indication of how this universal process works regardless of where a person lives. In regards to how well our senses operate, how our nervous system carries messages to and from the brain, and/or in how the brain processes the information, there can of course be differences from person to person.

Figure 4.1. Communication in the Nervous System

A. Receptor cells in each of the five sensory systems detect energy. The detection of physical energy emitted or reflected by physical objects is called sensation. The five sensory systems include vision, hearing, smell, taste, and touch.

B. This information is passed to the nervous system via the neural impulse and due to the process of transduction or converting physical energy into electrochemical codes. Sensory or afferent neurons, which are part of the peripheral nervous system, do the work of carrying information to the brain.

C. The information is received by brain structures (central nervous system) and perception occurs. What the brain receives is a lot of raw sensory data and this has to be interpreted, or meaning added to it, which is where perception comes in.

D. Once the information has been interpreted, commands are sent out, telling the body how to respond (Step E), also via the peripheral nervous system and the action of motor or efferent neurons.

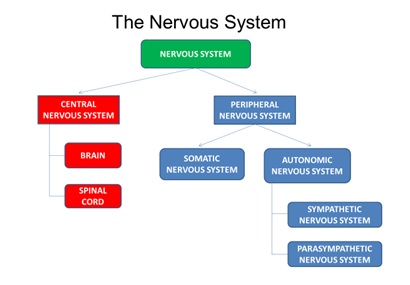

4.1.1.2. The parts of the nervous system. The nervous system consists of two main parts – the central and peripheral nervous systems. The central nervous system (CNS) is the control center for the nervous system which receives, processes, interprets, and stores incoming sensory information. It consists of the brain and spinal cord. The peripheral nervous system consists of the nervous system outside the brain and spinal cord. It handles the CNS’s input and output and divides into the somatic and autonomic nervous systems.

The somatic nervous system allows for voluntary movement by controlling the skeletal muscles and carries sensory information to the CNS. The autonomic nervous system regulates the functioning of blood vessels, glands, and internal organs such as the bladder, stomach, and heart. It consists of sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems.

The sympathetic nervous system is involved when a person is intensely aroused. It provides the strength to fight back or to flee (fight-or-flight instinct). Eventually the response brought about by the sympathetic nervous system must end. The parasympathetic nervous system calms the body.

For a visual breakdown of the nervous system, please see Figure 4.2 below.

Figure 4.2. The Structure of the Nervous System

4.1.2. Social Cognition

With this foundation set, let’s apply what we have learned to social psychology. Social cognition refers to the study of the process of collecting and assessing information about others so that we can draw inferences and form impressions about them. Consider the terms collecting and assessing in this definition. First, collecting. In Section 4.1.1. we defined sensation as detecting physical energy emitted or reflected by physical objects. This is what the definition of social cognition is referring to. Think about the students in your class or those you work with. What information do you collect or sense about them? Which sensory organs are you using? Do you see them? Smell them? Hear them? Now consider the lecture you might be experiencing. You see the professor move around the room or make gestures with their hands or face. You hear their words. You also see the lecture on the screen and form some impressions about the professor’s ability to present information on a slide based on the text that is included or the specific images that are used.

Once you have obtained this social information via the senses and the process of sensation, what do you do with it? Well, it is passed to the brain via the neural impulse and it is processed there. This ‘processing’ involves assessing the information we have obtained and adding meaning to it, and so assessing is the same as perceiving. We add some type of meaning to the raw sensory data.

We hope for now you understand how social cognition basically is an applied version of sensation and perception. Now we can dive more into what information we gather and how exactly we assess it.

4.1.3. The Information We Collect – The Work of Sensation

Go back to the answer you gave for what information you gather from others, whether in the class you are in or people you work with. What did it include? The information we gather or collect from our social world through the process of sensation is just one step in making an inference. In addition to collecting data, we also have to decide what information will be useful to us and then integrate it, the focus of Section 4.1.4. From this we can form a judgment, which will be discussed in Section 4.1.5.

4.1.3.1. Types of information: Physical cues. The information you notice first is probably what the person looks like or what they are wearing. We also notice behavior too. From this we infer certain qualities about them. What if we are working in the library and as we look around we see someone wearing all black, a satin bodice or corset, stripped stockings or tights, frilly or laced gloves, fishnet tights, spiker heels, sheer stockings or suspenders, dyed hair, piercings, sunglasses, silver skulls for jewelry, and/or blood red nail polish. This is not the typical person we see in a library and we might think they are there for a non-academic reason. Of course, on a university campus we see all different types of people and so diversity is not necessarily a shock. But this type of extreme behavior and appearance might be. As you will see shortly, we would then assign this person to the category Goth for which we have certain schemas.

4.1.3.2. Types of information: Salience. Our discussion of Goth in relation to physical cues leads to a discussion of salience or when something in our world stands out. A Goth individual in a library would be salient. If this same individual was at a Rave, they would likely not be regarded as engaging in strange or non-normative behavior. If we showed up wearing khakis and a polo shirt we might be considered out of place or salient. Consider that one of the principles of perceptual organization put forth by the Gestalt psychologists,called figure-ground. Figure-ground indicates that figure stands out against ground in our perceptual field. So, if a horse is running across a field, the horse would be figure and the field would be ground. The library would be ground in our example and the Goth individual is figure. Novel, colorful, noisy, smelly, strong tasting, or sticky stimuli are salient or stand out. From the perspective of sensation, you might say they attract our attention and are deemed emotionally important stimuli.

4.1.3.3. Types of information: Facial expressions. Another piece of information we obtain from others is their facial expression. If you tell a joke and the other person starts to smile (a genuine smile too) then you know your joke was funny and that you made them happy. If a doctor gives a patient news of a terminal illness, the patient will likely display a facial expression of shock or even concern. If a loved one was killed in a car accident you would likely display deep sadness, shock, and agony. So facial expressions provide us with information about what others are feeling.

4.1.3.4. Types of information: Personality traits. At the gym I attend on the campus of my university there is a girl who works there who is incredibly sociable, or extroverted, as the personality trait is termed. I usually listen to music as I work out, but she is so loud I can hear her over my music. I would not classify that information as being related to physical cues since she is dressed in the same uniform as her colleagues. You could say her behavior is different, as most employees do not laugh out loud or jump around, making it salient as well. From seeing how she acts, I have inferred she is the life of the party and likes being the center of attention, typical of extroverts. Learning this about her might lead me to make predictions about her future behavior. So, if I know she is due to work I will expect much of the same, slightly obnoxious behavior. You might make the case that if her behavior is subdued something is wrong. Consider this as we discuss attribution behavior in Section 4.2.

4.1.3.5. Types of information: Eye contact. What might the amount of eye contact a person makes say about them? If someone fails to ever make eye contact this could imply they have confidence issues, are feeling guilt or shame over some action, or are insincere. Think about a professor teaching a class. If they never look into the student’s eyes this could indicate they do not know the content that is being presented very well and is hoping no one questions them on it. On August 21, 2014 Forbes published an article on eye contact and stated that too much eye contact can be a bad thing too. Why is that? It could indicate that the person is intentionally trying to dominate, intimidate, or belittle another person and is seen as rude or hostile. But there are cases when we do maintain eye contact for longer periods of time such as when holding a more intense or intimate conversation. Generally, the greater the eye contact, the closer the relationship. Speakers who actively seek out eye contact are judged to be more believable, competent, and confident as with the case of our instructor. Finally, how much is the right amount of eye contact? Forbes says, “As a general rule, though, direct eye contact ranging from 30% to 60% of the time during a conversation – more when you are listening, less when you are speaking – should make for a comfortable productive atmosphere.” For more from this article, please visit: https://www.forbes.com/sites/carolkinseygoman/2014/08/21/facinating-facts-about-eye-contact/#a46d3391e26d.

4.1.3.6 Types of information: Moral character. When we gather information about others, we will also notice anything that speaks to their moral character. If the person is seen stealing money from a cash register or engaging in reckless behavior behind the wheel, we may assume they are egotistical, self-serving, or morally inept. If they stop to help an elderly person cross the street or to rescue someone trapped in a burning building, we will assume they are benevolent, just, and caring. Is it really that easy to judge the moral character of another person though? A 2017 article published by Science Daily points out that not only are deeds important, but so is the context. Work by Clayton Critcher of the Hass Marketing Group indicates that “people can do what is considered the wrong thing but actually be judged more moral for that decision.” Consider the following situation. John Q. Archibald is a factory worker facing a financial crisis due to his employer reducing paid hours. At the same time, his son, Michael, is stricken during a baseball game only to learn that the boy needs an emergency heart transplant. Though the parents do have health insurance, the policy will not pay for the procedure. John is able to convince heart surgeon, Dr. Raymond Turner, to reduce his fee for the surgery but still, the financial burden of the surgery is too much to bear. Faced with having to take their son home to die, John snaps and takes the staff and patients of the emergency room hostage. He becomes a media hero and the focus of intense media coverage, all while the police department tries to resolve the situation peacefully. So, was this a real life event? No. It is actually the plot of the Denzel Washington movie, John Q, from 2002, though director Nick Cassavetes experienced a real-life crisis that mirrored the events of the movie (See https://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/john_q/). What type of person should we assume John Q is? Is he a morally depraved person or was he more a victim of circumstance? Though he may have handled the situation differently, he was ultimately judged to be moral for his actions. What do you think you would do as a parent who experienced something similar with their own child? To read the whole Science Daily article, please visit: https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2017/05/170503092155.htm.

4.1.3.7. Types of information: Nonverbal communication. When we think of communication, we consider the words we say or write. But actions, and specifically body language, speaks louder than words. If you are talking to someone and they are slouched down, this may indicate they are not confident. What if they have locked their arms in front of themselves? Or what if they maintain an open body posture? This all provides us information about their intentions and personality. The distance someone stands from us also provides information. A person stands closer when they are friendlier and intimate with the other individual, such as how close you might stand in relation to your significant other compared to your boss or a coworker.

According to Psychology Today, it is believed that 55% of communication comes through our body language while 38% is derived from tone of voice and the final 7% from spoken words (Mehrabian & Wiener, 1967; Mehrabian & Ferris, 1967). But is this true? They say both yes and no as the formula applies to certain situations and so should not be used as the sole deciding factor in understanding the person’s behavior or the situation. Accuracy is increased if we consider the three C’s of nonverbal communication. First, we need to take into consideration the context of the situation or the environment it is taking place in, the history of the people engaged in meaningful discourse, and the role each person holds such as boss and employee or mother and child. Second, we should look for nonverbal gestures in clusters or groups so that no single gesture comes to define a person’s state of mind or emotion. The person who locks their arms can only be considered close-minded and resistant to new ideas or contradictory information if they engage in this behavior whenever they talk to other people. We are looking for a pattern of behavior. They may be standing like this right now because they are cold and trying to capture body heat but do not usually make this gesture. Finally, congruence or when our words match our body language is key. If you give a person bad news such as a loved one dying and they say they are fine when asked, their body language should be considered. If they have tears in their eyes or are showing other visible signs of being upset, their actions and words are not congruent and you should be concerned.

Source: https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/beyond-words/201109/is-nonverbal-communication-numbers-game

4.1.3.8. Negativity effect or positivity bias? Consider that negative aspects of a person’s behavior or personality stand out more and are attended to more, even when equally extreme positive information is present. This is called the negativity effect (Kellermann, 1984; 1989). One reason this might be so is that negative information could indicate a threat in our environment, especially if someone is displaying erratic behavior. Negative information leads us to ignore or reject other people and any additional information that may contradict this initial impression. So, we will continue seeing that person with erratic behavior in that way. The negativity effect has been documented in political perception (Klein, 1996; Lau, 1982), consumer familiarity with brands (Ahluwalia, 2002), trait ratings and free response impression descriptions (Vonk, 1993), and attitude change to a retailer following exposure to either moderately negative or positive publicity (Liu, Wang, & Wu, 2010), to name a few.

Despite this, we have a tendency to evaluate people positively, called the positivity bias. Consider that most behavior a person makes is positive since their actions are controlled by social norms and that we remember positive information more effectively than negative information. It is interesting to note that Dodds et al. (2015) found evidence for a positivity bias in human language such that, and supporting the Pollyanna hypothesis (Boucher & Osgood, 1969), positive words are more prevalent, hold more meaning, are used more diversely, and are easily learned. Their study involved the selection of 10,000 words from 10 different languages each.

Armed with this positive information about a person we then tend to assume other positive qualities, called the halo effect (Nisbett & Wilson, 1977). So, if a person is really nice, we will also assume they are attractive or intelligent. If rude, we will see them as unintelligent or unattractive. In an interesting application of the halo effect, Sine, Shane, and Di Gregorio (2003) explored whether institutional prestige affected the rate of annual technology licensing across 102 universities and from 1991-1998. Their results confirmed the presence of a halo effect such that universities with higher prestige had a higher licensing rate. One implication of this finding is important because as the authors state, “if external perceptions of organizations are narrow in scope and solely dependent on organizational past performance, then actors can use external perceptions to influence market transactions only in similar settings” (pg. 494) such that if the English or history departments are highly ranked nontechnical departments, the university could use this external perception to license more of its inventions.

4.1.3.9. The role of our emotional state on the information we attend to. How might you interpret a person’s behavior or words if you are in a good mood? What about if in a bad mood? Perceptual set indicates the influence of our beliefs, attitudes, biases, stereotypes, and … well, mood, on how we perceive and respond to events in our world! We might regard a joke our friend says as funny when we are happy but see it as ill-timed or out of poor taste if we are in a bad mood, depending on the nature of the stressor that placed us in a bad mood.

4.1.3.10. Deception in revealing who we are. We sometimes employ deception in our interactions with others as a way to mask our true feelings or intentions, or to spare their feelings. Nonverbal leakage (Ekman & Friesen, 1969) refers to the fact that when we are interacting with another person, we have a tendency to focus more on what we are saying and less on what we are doing. As such, our true motives may be revealed indirectly. For instance, you might have received a gift from your significant other last Christmas that you did not like, but still smiled upon opening it and told this person how much you liked it. A smile that reflects genuine happiness is called a Duchenne smile while a fake smile is called a non-Duchenne smile. Could you tell the two apart if you were wondering if your significant other liked the give you gave him/her?

Also, microexpressions are facial expressions that are made briefly, involuntarily, and last on the face for no more than 500 milliseconds (Yan et al., 2013). It is possible that being able to read them could reveal a person’s true feelings on a matter (Porter & Brinke, 2008) and evidence exists for the ability to train people to read these facial expressions (Matsumoto & Hwang, 2011). This skill would be particularly useful for law enforcement officials (Ekman & O’Sullivan, 1991).

4.1.4. The Meaning We Assign When We Assess – The Work of Perception

4.1.4.1. Categories and schemas. One way we assign meaning is to use the information we collected to assign the person to a category or group, which makes them seem less like distinct individuals. Each category has a schema or a set of beliefs or expectations about the group that are presumed to apply to all members of the group and are based on experience we have had with other members of that group. For instance, you likely have assigned the instructor of your social psychology class to the group, professor, for which you have a schema and specific beliefs or expectations such as this person being formal, eccentric, very intelligent, gifted at oration, organized, and tolerant. This is based on your past experiences with course instructors and maybe even what you learned from others (secondhand information).

4.1.4.2. Types of schemas. We have several types of schemas that we use to assign meaning to our world. First, there are role schemas, which relate to how people carrying out certain roles or jobs are to act. For instance, what it the role schema you have for someone working in your Human Resources office at work? What about the cashier at your local grocery store?

Another schema we have is called the person schema and relates to certain types of people such as firefighters, geeks, or jocks. For each of these people, we have specific beliefs and expectations about what their personality is like and how they are to behave in various situations. What traits do you believe cheerleaders hold?

The final schema is called an event schema or script. This type of schema tells us what is to occur in certain situations such as at a party or in a chemistry lab. The parking garage I use daily requires me to swipe my card as I enter. Now the garage houses more than just those with my special permit. It is used as a public parking lot too. Recently, the gate as you exit has been broken and so left up. Usually when I leave I would swipe my card again, thereby causing the gate to go up. What I have to do when entering and exiting the lot is usually pretty clear. Since the gate is just up now, I have been confused what to do when I get to the pay station. I have been trying to swipe my card again but really, it’s not needed. The gate is up already. I finally asked what to do and the parking attendant told me that those with parking permits can just pass through. Until this point, I was afraid to just go through, even though I have an orange permit sticker on the bottom left of my windshield. I was not sure if the university would consider my behavior to be trying to skip payment and send the police after me. The broken gate has left my event schema in turmoil. Hopefully it is fixed soon. That is the gate, not my event schema. I guess you could say by fixing the gate they restore my event schema too.

Let’s put them all three schemas together. Imagine you are at a football game for your favorite team, whether high school, college, or professional. Who are some of the people there? Fans, coaches, players, referees, announcers, cheerleaders, and medical staff are all present. We expect the fans to be rowdy and supportive of the team by doing the wave or cheering. We expect the head coach to make good decisions and to challenge poor decisions by the referees. To that end, we expect the referees to be fair, impartial, and accurate in the judgments they make. We would not be surprised if they threw a flag or blew a whistle. Cheerleaders should be peppy, cheerful, and do all types of gymnastics on the field and waive pom poms. Etc… These are the main people involved in the football game. In terms of roles, the head coach fulfills the role of leader of the team along with the Quarterback. The role of promoting team spirit and energizing the crowd goes to the cheerleaders and maybe some key players on the field. The medical staff are there to diagnose and treat injuries as they occur and so their role is to keep everyone safe. Finally, what do we do as a fan when we attend a football game? We have to enter the stadium and likely go through a search of our bags and present our ticket. We walk to our assigned seat. Though we cheer our team on, we need to be respectful of those around us such as not yelling obscenities if children are nearby. We also are expected to participate in the wave and sing the team’s fight song. Etc…. These are the event schemas that dictates our behavior.

Other types of schemas are worth mentioning. A group stereotype includes our beliefs about what are the typical traits or characteristics of members of a specific group. We will discuss this in more detail in Module 9. Prototypes are schemas used for special types of people or situations while exemplars are perfect examples of that prototype. If we are starting a new job we will have a prototype for what a boss is and then compare our new boss against really good, and really bad, bosses we have had in the past.

4.1.4.3. The benefits of schemas. When we meet someone, we collect the aforementioned information and use it to place them in a category for which we have a schema. If this sounds like a pretty simple and automatic process, you are correct. As such, it should not be surprising to learn that schemas make cognitive processing move quicker. But they also complete incomplete pictures in terms of what we know about someone. Though we may not know Johnny personally, placing him in the schema football player helps us to fill in these blanks about what his personality is like and how he might behave. Using our schema for football player we can now predict what a future interaction with Johnny might involve. Let’s say he is assigned to be our lab partner in chemistry. We use our schema to make a quick assessment if the experience of working with him might be pleasant or unpleasant and we might be able to predict what his level of involvement in the project will be as well as the potential quality of his work.

4.1.4.4. The accuracy of our schemas. To reap the benefits of schemas they have to be accurate. So how accurate are our schemas? Think about the last party you attended. Let’s say that a guy, John, sees a girl, Alyssa, whom he thinks is cute and goes up to talk to her. Before even saying a word, John has gathered a lot of information about Alyssa. He sees the clothes she is wearing, smells her perfume as he gets closer, and maybe can hear her talk. They have a brief conversation in which he gathers additional information through the words she uses, how she talks, her facial expressions, voice inflections and tone, and her body language. He uses this information to classify Alyssa as an introvert. Let’s face it, she seemed very shy and reserved and not the outgoing life of the party he thought she was, or maybe heard from others. John has just taken this information to place Alyssa in a category, introverted, for which he has a very clear schema. Is he correct? Possibly. But what if he later learns from another friend that Alyssa’s cat of 10 years died earlier that day and that she was incredibly sad about it? Will he change his schema and give her a second chance?

Likely not. Due to what is called belief perseverance, John will maintain the schema he already formed. As such, we really need to consider our initial interaction with a stranger as this first impression, called the primacy effect, is likely to stick even if we receive contradictory information later. Alyssa is now, and will forever be, an introvert in John’s mind. This seems almost illogical in some way but work by Guenther and Alicke (2008) suggest that belief perseverance occurs because we are motivated to maintain a relatively favorable self-image and so discredited feedback given to participants about their performance on a word-identification task threatens an important aspect of their self-concept. In a classic study of belief perseverance, Carretta and Moreland (1982) conducted a field demonstration and assessed voter perceptions of Richard Nixon shortly before the U.S. Senate’s Watergate hearings began, during the Memorial Day recess, and just after testimony by John Dean. Results showed that respondents who said they voted for Nixon in 1972 persisted in their positive evaluation of him while those who voted for McGovern became more negative in their beliefs.

Finally, confirmatory hypothesis testing occurs when we select information from others that confirms an existing belief or schema. If we believe, for instance, that a person is trying to take advantage of us we will only take note of behaviors that indicate manipulation and ignore other behaviors in which they may be trying to help us.

So though schemas make processing quicker and more complete, they could also lead us to drawing the wrong conclusion or oversimplifying a situation. This in turn may bias us in future interactions with a person or group and to maintain the content of our schema even if information to the contrary is experienced.

4.1.4.5. Schemas and memory. Schemas might be regarded as filters of sort, affecting three different memory processes. First, they affect what specific aspects of our environment we attend to. In general, information not consistent with an existing schema is ignored unless it is so extreme, we have no choice but to attend to it (Fiske, 1993). Second, the long-term memory process of encoding is when we attend to, take in, and process information, which for our purposes leads to the formation of a schema. Information consistent with an existing schema is easier to remember but if the schema has not formed yet, information that is inconsistent with it is easier to remember (Stangor & Ruble, 1989). Finally, and related to the process of retrieval, Conway and Ross (1984) found that when a schema is activated, we tend to recall information that makes up the schema or is congruent with it. Memory research further confirms this finding in that a sin of omission is what is called the consistency bias, or our tendency to recall events in a way consistent with our beliefs and biases. Also, the misinformation effect occurs when we receive misleading information about a recently witnessed event and then incorporate this inaccurate information into our memory of the event (Loftus & Hunter, 1989; Loftus, 1975).

4.1.4.6. Schemas and behavior. There are times when predictions are made about us or by us that eventually come true since we engage in behavior that confirms these expectations. We call these self-fulfilling prophecies (Merton, 1948) and they show one way that schemas affect our behavior. Maybe you have been told you will be really bad at bowling because you are not coordinated enough, or your arm is not strong enough to hold the ball. You go bowling and sure enough, they were right. Your ball spends more time in the gutter than down the middle of the lane. Pikhartova, Bowling, and Victor (2015) found that in a sample of 4465 participants aged 50 and over, stereotypes and expectations about being lonely later in life were significantly associated with self-reports of loneliness 8 years later. The authors suggest that interventions be developed to change age-related stereotypes at the population level to reduce loneliness in the elderly.

What if we led teachers to believe some kids were really good at math while others were horrible at it? What do you think might happen to the children’s performance? Sure enough, when teachers were led to expect enhanced performance, they got it. The same was true for poor performance (Rosenthal & Jacobson, 1968). The effect holds true today as well. For instance, Friedrich et al. (2015) found that in a sample of 73 teachers and 1289 5th grade students that teacher expectancies affected grades and achievement test scores at the individual level, student’s self-concept partly mediated teacher expectancy effects, and the teacher effect disappeared at the classroom level when student’s prior achievement was controlled for. This tendency for students to perform as teachers expect them to is called the teacher expectancy effect or Pygmalion effect and is a type of self-fulfilling prophecy. Teachers hold certain beliefs and expectations about the personality and behavior of poor and exceptional students and this in turn affects their performance.

Another way we see the self-fulling prophecy play out is in respect to what are called placebos. Consider that if a patient knows they are in the experimental drug group which is meant to cure depression, they will likely show marked reduction in depression compared to a control group that knew they received no help to reduce their depressive thoughts. Are the results of the study due to the actual action of the new drug, or due to the expectations the participants had of the drug’s ability to ‘cure’ their depression? We really do not know. By telling them they are in the drug group, the researcher obtains the exact results they expected…or the improvement of the group is a self-fulfilling prophecy. To know if the drug is as good as we think it is, two groups are used and both groups are given a pill. One is the experimental drug and a second, the placebo or sugar pill, looks identical to the drug. By appearing the same and both groups receiving a pill, no participant knows which group they have been randomly assigned to and cannot affect the results of the experiment.

4.1.4.7. Schemas and heuristics. As we saw above, schemas do aid us in pretty important ways. We cannot really process all the sensory information we collect on a daily basis on a deeper level, and so we have to make quick judgments. But as we also saw, this can be done in error at times. To round out this section, we thought it would be good to discuss common cognitive errors we make in the form of heuristics, or mental shortcuts used to solve problems or to help explain ambiguous information.

First, the representativeness heuristic (Kahneman & Tversky, 1972) takes information we sense or collect from our environment and matches it against existing schemas, to determine if the match is correct. We attempt to determine how likely something is by how well it represents a prototype. Of course, the problem is that we may ignore other information that is relevant. Arising from the representativeness heuristic is the conjunction error which occurs when a person assumes that events that appear to go together will occur together. Consider the following: “Linda is 31 years old, single, outspoken, and very bright. She majored in philosophy. As a student, she was deeply concerned with issues of discrimination and social justice, and also participated in anti-nuclear demonstrations.” What if you were given a set of occupations and avocations associated with Linda and asked to what degree does she resemble the typical members of her class? These included Linda being an elementary school teacher, Linda working in a bookstore and taking yoga classes, Linda being active in the feminist movement, Linda being a psychiatric social worker, Linda being a bank teller, Linda being an insurance salesperson, and Linda being a bank teller and active in the feminist movement. Results showed that of 88 undergraduate students, 85% predicted that she was a bank teller and active in the feminist movement. The students ranked the conjunction (Linda being a bank teller and active in the feminist movement) as more probable than the two avocations separately (Tversky & Kahneman, 1983).

What if you were asked how fast a fellow sprinter on the track team was? To figure out the answer you would compare her speed with your own. If you determine she is faster than you, then your response would be she is very fast. But if slower than you, you would say she runs slow. The anchoring and adjustment heuristic (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974) helps us answer questions such as this by starting with an initial value, oftentimes the self, when asked to make a social judgment, and then adjust accordingly. But is the self enough? Results of two sets of experiments show that adjustments “…tend to be insufficient because people tend to stop adjusting soon after reaching a satisfactory value, and adjustment-based anchoring biases are reduced when people are motivated and able to think harder than they might normally” (Epley & Gilovich, 2006, pg. 316).

We also have a tendency to focus on distinctive features of a person and ignore or underuse information that describes most people, called the base-rate fallacy. We tend to be influenced by outliers in our data about this group, or by extreme members. Think about the last football game you attended. If some fans of the visiting team acted rowdy and were hostile to the players from your team, you would tend to see all fans of this team in this way. Of course, you would be wrong. An explanation of why we commit this fallacy is that people order information by its perceived degree of relevance and so information deemed to be highly relevant will dominate or take precedence over low-relevance information (Bar-Hillel, 1980).

4.1.5. The Results of Social Cognition: The Judgments We Form

4.1.5.1. Factors on our judgments. Several factors affect the judgments we make. First, consider that our judgment of a person or situation could be affected by biased information we have received. Maybe we have decided that a new colleague we have had limited contact with is not a nice person due to what a friend tells us about them. Of course, we do not know that our friend does not like this individual for personal reasons and nothing specific that the person has done. Hence, the friend has affected our judgment of the new employee by providing us with biased information. Additionally, we may make an inference about a person or group based on a very limited amount of information. Maybe we are only basing our opinion of the person on what we heard about them from a few others (assume the information is not biased) or when we saw them walking down the hall. How can you really make any type of accurate judgment in this situation?

What we expect of this person could be based on prior expectations which can be faulty. Maybe we remember that the person who held their job previously was fairly incompetent and lazy and so we believe them to be so. You may not realize how this faulty prior expectation is affecting your current expectation of the new current worker and that it may stop you from collecting information about the new worker that suggests he/she will be a model employee and colleague.

Priming occurs when a word or idea used in the present affects the evaluation of new information in the future (Tulving & Schachter, 1990). In a prototypical experiment such as using a word-stem completion test, participants are asked to study a series of words and then a delay of several minutes to several hours occurs. They are then given three-letter word stems with multiple possible completions and asked to complete each stem with whatever word comes to mind such as being given most and then finishing it with motel or mother. Participants tend to complete the stems with words that were studied earlier than words that were not (Schacter & Buckner, 1998). In one study, researchers unobtrusively primed economic schemas (knowledge structures that emphasize being rational, efficient, and self-interest) and found that the compassion individuals expressed to others decreased as compared to the control condition. This effect was mediated by dampened feelings of empathy and making the expression of emotions seem unprofessional. Mundane and psychological realism was obtained by presenting working managers with situations they would likely encounter in their professional roles such as delivering negative feedback to a team member or transferring an employee to an undesirable city, asking participants to write a letter they believed would be delivered to a student about loss of their scholarship, or making time to meet with recipients of bad news about the loss of a scholarship or being cut from the soccer team (Molinsky, Grant, & Margolis, 2012).

One other factor on the judgments we form is framing or the way in which choices are presented to us (Tversky & Kahneman, 1981). If, for instance, a friend tells you the choice to go to Washington State University is ‘a great opportunity for you,’ you will view it in favorable terms. In contrast, if the friend says that ‘it’s not the worst school you could attend,’ you would likely have an unfavorable impression. Would you choose a sure gain of $240 or a 25% chance to gain $1,000/75% chance to gain nothing? 84% percent chose the first choice. Or what if you had an 80% chance to win $45 or a 10% chance to gain $30? In this case 78% went with the sure thing. One final example is useful. “Imagine that you have decided to see a play where admission is $10 per ticket. As you enter the theater you discover that you have lost a $10 bill. Would you still pay $10 for a ticket for the play?” If you said yes, you are like the 88% of participants who did so too. But what if you paid $10 to see the play but as you entered the theater you realized that you lost your ticket. You never made note of the seat and the ticket cannot be recovered. Would you pay another $10 for a ticket? Fifty-four percent said no while 46% said yes. On which side did you fall? (Tversky & Kahneman, 1981)

4.1.5.2. Affective forecasting. As we have seen throughout this module, emotions play a large role in how we make decisions and interpret the world around us. It should be no surprise that they also affect the decisions we make about our future, called affective forecasting. Buehler and McFarland (2001) asked students to predict their affective reactions to a wide variety of positive and negative future events. The results of five studies confirmed that participants anticipated more intense reactions to these events than what was experienced. They also found that participants anticipated stronger reactions when they focused narrowly on the upcoming event and neglected to consider past experiences and less intense reactions that they have had. Emotional intelligence or EI is our ability to manage the emotions of others as well as ourselves and includes skills such as empathy, emotional awareness, managing emotions, and self-control. We might expect that individuals high in EI would be better at affective forecasting than those low in EI. Research confirms this hypothesis (Dunn et al., 2007).

4.1.5.3. How accurate are our judgments? When it comes to the accuracy of our judgments, we have a tendency to overestimate just how good we are, called the overconfidence phenomenon. Doctors are not immune from this error in thinking. One study found that physicians were highly confident they made the correct choice in treating breast cancer though there was no consensus on what the best treatment would be across physicians (Baumann, Deber, & Thompson, 1991). According to Moore and Healy (2008) overconfidence takes three forms. First, is the overestimation of our ability, performance, chance of success, or level of control. A student believing he earned an A on an exam when in reality he earned a C is an example. Second, people tend to believe they are better than others which the authors call overplacement. If that same student believed he had the highest grade in the class when in reality most of the class scored above him, he would be committing overplacement. Finally, overprecision occurs when we are excessively certain about the accuracy of our beliefs. The authors assert that these sources of overconfidence are presumed to have the same underlying psychological causes, when in fact they do not.

4.2. Attribution Theory

Section Learning Objectives

- Define attribution theory.

- Describe the two types of attributions we might make.

- Explain the correspondent inference theory.

- Explain the covariation theory.

- List and describe types of cognitive errors we make in relation to explaining behavior.

4.2.1. Defining Terms

Have you ever wondered why the person driving down the road is swerving in and out of traffic, why your roommate doesn’t clean up behind him or herself, why your kids choose to play video games over studying for the SAT, or why your boss seems to hate you? If so, you are trying to explain the behavior of others and is a common interest many students have in pursuing psychology as a major and career. Simply, it comes down to the question of why. According to attribution theory (Heider, 1958), people are motivated to explain their own and other people’s behavior by attributing causes of that behavior to either something in themselves or a trait they have, called a dispositional attribution, or to something outside the person called a situational attribution.

4.2.2. Correspondent Inference Theory

The correspondent inference theory (Jones & Davis, 1965) provides one way to determine if a person’s behavior is due to dispositional or situational factors and involves examining the context in which the behavior occurs. First, we seek to understand if the person made the behavior of their own volition or if it was brought on by the situation. If the behavior was freely chosen, then we use it as evidence of the person’s underlying traits. For example, President Trump has proven to be a controversial figure in the United States and the reader of an article showcasing his successes in the first two years should be careful not to assume that the reporter supports him. Likewise, if the article was critical of his performance this does not mean that the reporter is against him. Either reporter may have been tasked with writing the article by their editor, meaning that the information presented was situationally driven and not necessarily reflective of the reporter’s personal beliefs (i.e. not dispositional).

Second, we need to consider the outcome produced by the person’s behavior. If several outcomes have been produced it will be hard to discern the motive of the individual. If only one outcome resulted from the behavior, then we can determine a motive with greater confidence.

Third, we need to examine whether the behavior was socially desirable or undesirable. If the former, we cannot confidently determine the motive for the behavior meaning that the positive behavior may not really result from their unique traits. If the behavior is undesirable, then we can assert that a dispositional attribution is the cause. Consider a first date. If the person seems extra nice, accommodating of your desires, funny, and/or smiles a lot, we cannot really say it is because this is the type of person they are. It may simply be they are trying to present themselves in the best light to make a good first impression. If, on the other hand, the person seems very shy or egotistical, we will attribute this behavior to be representative of the type of person they are.

Fourth, what if you go into your local cell phone dealer because of a problem with your phone. If the technician is extremely nice, can we say this reflects the type of person they are, or is it due to the position they are in? Jones and Davis (1965) therefore says we need to consider if a social role is at work and in the case of our technician, their niceness may be due to their customer service-oriented job (situational) and not being high in the personality trait of agreeableness (dispositional).

4.2.3. Covariation Theory

Kelley (1967; 1973) proposed his covariation theory which says that something can only be the cause of a behavior if it is present when the behavior occurs but absent when it does not occur and that we rely on three kinds of information about behavior: distinctiveness, consensus, and consistency. For this discussion let’s use the example of a professor who requests that you stay after class (i.e. you want to know why they asked you to stay). First, distinctiveness asks whether the behavior is distinct or unique. In the case of this example, we would ask whether this professor usually asks students to stay after class. If they do ask students to stay (low distinctiveness), you will think they have personal reasons for talking with you. If they do not (high distinctiveness), you will see it as unusual and figure it has something to do with you and not them (i.e. they asked you to stay for situational reasons).

Second, consensus asks whether there is agreement or whether other instructors ask you to stay and talk to them after class. If yes (high consensus), the request is probably due to some external factor such as the professors being on your honors thesis committee and are inquiring about your progress (situational). If other professors do not ask you to stay after class (low consensus), the request is probably due to an internal motive or concern in your instructor (dispositional).

Finally, consistency asks whether the behavior occurs at a regular rate or frequency. In the case of our example, you will ask yourself whether that professor regularly asks you to stay. If yes (high consistency), you will think it is like the times before and think nothing of it (dispositional). If no (low consistency), you will think they requested the conference due to something you said or did in class (situational).

Kelly (1987) also proposed the discounting principle which states that when more than one cause is possible for a person’s behavior, we will be less likely to assign any cause. For example, if a coworker is extra nice to the boss and offers them a ride home, we might make a dispositional attribution, unless we also know that this coworker is up for a raise or promotion. In the case of the latter, no attribution may be made because the person could be acting nice as usual or simply looking to influence the boss and get the desired advancement.

4.2.4. Cognitive Errors When Explaining Behavior

The theories presented up to this point to explain how we assign a cause to behavior make it seem like we undergo a cognitively rigorous and logical process to make the determination. Though this may be true in some circumstances, most situations occur so quickly that we really do not have the time to commit. As such, we take mental shortcuts, called heuristics, which could lead to accurate determinations but also incorrect ones.

4.2.4.1. Fundamental attribution error. First, we might make the fundamental attribution error (FAE; Jones & Harris, 1967) which is an error in assigning a cause to another’s behavior in which we automatically assume a dispositional reason for their actions and ignore situational factors. In other words, we assume the person who cut us off is an idiot (dispositional) and do not consider that maybe someone in the car is severely injured and this person is rushing them to the hospital (situational).

Hooper et al. (2015) wanted to know if perspective taking (PT; Parker & Axtell, 2001), or when we adopt another person’s point of view, could be used to reduce the FAE. Using a sample of 80 individuals from the general public with a mean age of 25.23 years, participants were divided up into one of four groups – one which completed PT training and watched a video in favor of capital punishment; a second which completed PT training and watched a video against capital punishment; a third which received no training and watched a video for capital punishment; and finally a group which received no training and watched a video against capital punishment. Results showed that both control groups (those receiving no PT training) committed the FAE at a higher rate than those with PT training. The authors note that even just a brief perspective taking intervention could improve everyday interactions in which the FAE is committed.

4.2.4.2. Self-serving bias. When we attribute our success to our own efforts (dispositional) and our failures to outside causes (situational), we are displaying the self-serving bias. Please refer back to Section 3.4.1. for a discussion of it.

4.2.4.3. Belief in a just world. Do people get what they deserve? The belief in a just world (BJW) hypothesis (Lerner, 1980) states that good things happen to good people and bad things happen to bad people. A study examining 458 German and Indian high school student’s BJW and their bullying behavior was conducted and considered the mediational role of teacher justice. Analyses showed that the stronger the belief in BJW the more students saw their teacher’s behavior toward them to be just and the less bullying they reported. The results held when sex, country and neuroticism were controlled for (Donat et al., 2012). Cross cultural differences have also been found in a general BJW (GBJW) and a personal BJW (PBJW) such that Chinese adults and adolescents, adolescents in a poverty stricken area, and adults surviving high exposure to post-earthquake trauma endorsed a GBJW which then predicted psychological resilience in the three samples, all of which contrasts with individualistic cultures that endorse PBJW (Wu et al., 2010). Another study (Stromwall, Alfredsson, & Landstrom, 2012) found that victims of rape were attributed higher levels of blame when the participant was high on BJW, and more so when the perpetrator was known to the victim.

4.2.4.4. Actor-observer bias. Fourth, the actor-observer bias occurs when the actor overestimates the influence of the situation on their own behavior while the observer overestimates the importance of the actor’s personality traits on the actor’s behavior (dispositional; Jones & Nisbett, 1972). An example might be a professor (observer) deeming that a student did not do well because they were lazy and did not study (i.e. dispositional) while the student (the actor) feels that their lack of success on an exam was due to the professor making an incredibly hard exam (i.e. situational).

4.2.4.5. Availability heuristic. What if we were to ask you are there are more words in the English language that begin with the letter r or are there more words with r as the third letter. What would your answer be? If you are like the 152 participants in Tversky and Kahneman’s (1973) study, you would likely say the first position. In fact, 105 participants did while 47 said the third position. The researchers called this the availability heuristic or our tendency to estimate how likely an event is to occur based on how easily we can produce instances of it in our mind. It is easier to think of words beginning with r than it is to think of words with r as the third letter, even though the latter is more likely in the English language. An interesting study of Facebook users (Chou & Edge, 2012) proposed that those with deeper involvement with Facebook would have different perceptions of others because they tend to base judgments on easily recalled examples (the availability heuristic) and they attribute positive content presented on the social networking site to the person’s personality rather than situational factors (FAE). Results showed that those who used Facebook longer agreed more that others were happier than they were and agreed less that life is fair, while those using it more each week (in terms of number of hours) agreed more that others were happier and had better lives. The authors say that, “looking at happy pictures of others on Facebook gives people an impression that others are “always” happy and having good lives, as evident from these pictures of happy moments” (pg. 119) but they fail to pay attention to the circumstances that affect these people’s behavior.

4.2.4.6. Counterfactual thinking. Have you ever wondered what your life might have been like if you went into the military instead of going to college? Or what if you did not ask your significant other out on a first date? Or if you had said no instead of yes (or vice versa) to whatever situation you can imagine? These “what might have been” situations we imagine are called counterfactual thinking and according to Summerville and Roese (2008) they are an essential feature of healthy cognitive and social functioning. They can lead to feelings of regret or envy if we compare the life we have now to a better one (Coricelli & Rustichini, 2010) or relief if we realize that our current life could be worse; respectively making an upward comparison for the former and a downward comparison for the latter). Kray et al. (2010) further assert and demonstrate across four experiments that counterfactual thinking can facilitate the construction of meaning. For instance, in one experiment they found that participants who were asked to consider counterfactual alternatives to why they decided to attend Northwestern said their choice was more meaningful and significant compared to those in the control condition. The same was true when participants were asked to consider counterfactual alternatives to meeting a close friend and deciding on the importance of a turning point in their life (i.e. was it a product of fate?). In the case of the turning point, the authors write, “Rather than leading one to conclude that life could have easily unfolded differently, it appears that the fact of mentally undoing a turning point enhanced the perception that fate drove its occurrence” (pg. 110).

4.2.4.7. Wishful seeing. Do you think people tend to see what they want to see? Research suggests they do (Dunning & Balcetis, 2013). Across five experiments, Balcetis and Dunning (2010) provide empirical support for what is called wishful seeing. In the first experiment, they asked participants to measure how far away (in inches) a water bottle was from their current position after feeding one group pretzels that made up 40% of their daily intake of sodium (thirsty condition) and allowing another group to drink as much water as they wanted to from four, 8-oz glasses (quenched condition). Participants also indicated how long it had been since they last consumed a beverage, rated on a 7-point scale how thirsty they were, and finally rated on the same scale how appealing a bottle of water was. The two groups did not differ significantly in terms of how long it had been since they drank and those who ate pretzels reported greater levels of thirst. Thirsty participants rated the bottle of water as more appealing and perceived the water bottle as closer than quenched participants. In a second experiment, 123 students of Ohio University reported a $100 bill as closer if they had a chance of winning it compared to a group that had no chance of winning it. The researchers also found that students randomly assigned to a condition receiving positive feedback about their sense of humor estimated their personality test clipped to a stand 72 in. away was closer than groups receiving negative feedback. A third experiment showed that participants (40 students completing the study for course credit) underthrew a bean bag when a gift card was valued at $25 then when it had no value, indicating that they believed the gift card was closer than it really was when the value was higher. In all experiments, Balcetis and Dunning (2010) found that perceptions of distance depend at least in part on how desirable the perceived object was. When we perceive desirable objects as closer, we can engage in motivated behavior to obtain these objects.

4.2.4.8. False uniqueness and consensus. It should also be pointed out that the false uniqueness and false consensus effects discussed in Module 3 relate here as well. Please see Section 3.4.2. for a discussion.

Module Recap

That’s it. In Module 4 we discussed how we perceive the world around us, called person perception, and using social cognition. This involves collecting information via the senses and then adding meaning to this raw sensory social information. We add meaning by assigning people to categories for which we have schemas. We then form judgments, but they can be inaccurate at times. We also try and understand a person’s behavior by attributing the cause to dispositional or situational factors. With self and person perception now covered, we move to Module 5 and a discussion of attitudes.

2nd edition