Module 12: Attraction

Module Overview

It was important to end the book on a positive note. So much of what is researched in social psychology has a negative connotation to it such as social influence, persuasion, prejudice, and aggression. Hence, we left attraction to the end. We start by discussing the need for affiliation and how it develops over time in terms of smiling, play, and attachment. We will discuss loneliness and how it affects health and the related concept of social rejection. We will then discuss eight factors on attraction to include proximity, familiarity, beauty, similarity, reciprocity, playing hard to get, and intimacy. The third section will cover types of relationships and love. Finally, relationship issues are a part of life and so we could not avoid a discussion of the four horsemen of the apocalypse. No worries. We end the module, and book, with coverage of the beneficial effects of forgiveness.

Module Outline

- 12.1. The Need for Affiliation

- 12.2. Factors on Attraction

- 12.3. Types of Relationships

- 12.4. Predicting the End of a Relationship

Module Learning Outcomes

- Describe the need for affiliation and the negative effects of social rejection and loneliness.

- Clarify factors that increase interpersonal attraction between two people.

- Identify types of relationships and the components of love.

- Describe the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse as they relate to relationship conflicts, how to resolve them, and the importance of forgiveness.

12.1. The Need for Affiliation

Section Learning Objectives

- Define interpersonal attraction.

- Define the need for affiliation.

- Report what the literature says about the need for affiliation.

- Define loneliness and identity its types.

- Describe smiling and how it relates to affiliation.

- Describe play and how it relates to affiliation.

- Define attachment.

- List and describe the four types of attachment.

- Clarify how attachment to parent leads to an attachment to God.

- Describe the effect of loneliness on health.

- Describe social rejection and its relation to affiliation.

12.1.1. Defining Key Terms

Have you ever wondered why people are motivated to spend time with some people over others, or why they chose the friends and significant others they do? If you have, you have given thought to interpersonal attraction or showing a preference for another person (remember, inter means between and so interpersonal is between people).

This relates to the need to affiliate/belong which is our motive to establish, maintain, or restore social relationships with others, whether individually or through groups (McClelland & Koestner, 1992). It is important to point out that we affiliate with people who accept us though are generally indifferent while we tend to belong to individuals who truly care about us and for whom we have an attachment. In terms of the former, you affiliate with your classmates and people you work with while you belong to your family or a committed relationship with your significant other or best friend. The literature shows that:

- Leaders high in the need for affiliation are more concerned about the needs of their followers and engaged in more transformational leadership due to affiliation moderating the interplay of achievement and power needs (Steinmann, Otting, & Maier, 2016).

- Who wants to take online courses? Seiver and Troja (2014) found that those high in the need for affiliation were less, and that those high in the need for autonomy were more, likely to want to take another online course. Their sample included college students enrolled in classroom courses who had taken at least one online course in the past.

- Though our need for affiliation is universal, it does not occur in every situation and individual differences and characteristics of the target can factor in. One such difference is religiosity and van Cappellen et al. (2017) found that religiosity was positively related to social affiliation except when the identity of the affiliation target was manipulated to be a threatening out-group member (an atheist). In this case, religiosity did not predict affiliation behaviors.

- Risk of exclusion from a group (not being affiliated) led individuals high in a need for inclusion/affiliation to engage in pro-group, but not pro-self, unethical behaviors (Thau et al., 2015).

- When affiliation goals are of central importance to a person, they perceive the estimated interpersonal distance between them and other people as smaller compared to participants primed with control words (Stel & van Koningsbruggen, 2015).

Loneliness occurs when our interpersonal relationships are not fulfilling and can lead to psychological discomfort. In reality, our relationships may be fine and so our perception of being alone is what matters most and can be particularly troublesome for the elderly. Tiwari (2013) points out that loneliness can take three forms. First, situational loneliness occurs when unpleasant experiences, interpersonal conflicts, disaster, or accidents lead to loneliness. Second, developmental loneliness occurs when a person cannot balance the need to relate to others with a need for individualism, which “results in loss of meaning from their life which in turn leads to emptiness and loneliness in that person.” Third, internal loneliness arises when a person has low self-esteem and low self-worth and can be caused by locus of control, guilt or worthlessness, and inadequate coping strategies. Tiwari writes, “Loneliness has now become an important public health concern. It leads to pain, injury/loss, grief, fear, fatigue, and exhaustion. Thus, it also makes a person sick and interferes in day to day functioning and hampers recovery…. Loneliness with its epidemiology, phenomenology, etiology, diagnostic criteria, adverse effects, and management should be considered a disease and should find its place in classification of psychiatric disorders.”

What do you think? Is loneliness a disease, needing to be listed in the DSM?

12.1.2. Development of Affiliation and Attachment

12.1.2.1. Smiling and affiliation. As early as 6-9 weeks after birth, children smile reliably at things that please them. These first smiles are indiscriminate, smiling at almost anything they find amusing. This may include a favorite toy, mobile over their crib, or even another person. Smiles directed at other people are called social smiles. Like smiles directed at inanimate objects, they too are indiscriminate at first but as the infant gets older, come to be reserved for specific people. These smiles fade away if the adult is unresponsive. Smiling is also used to communicate positive emotion and children become sensitive to the emotional expressions of others.

This indiscriminateness of their smiling ties in with how they perceive strangers. Before 6 months of age, they are not upset about the presence of people they do not know. As they learn to anticipate and predict events, strangers cause anxiety and fear. This is called stranger anxiety. Not all infants respond to strangers in the same way though. Infants with more experience show lower levels of anxiety than infants with little experience. Also, infants are less concerned about strangers who are female and those who are children. The latter probably has something to do with size as adults may seem imposing to children.

Important to stranger anxiety is the fact that children begin to figure people out or learn to detect emotion in others. They come to discern vocal expressions of emotion before visual ones, mostly due to their limited visual abilities early on. As vision improves and they get better at figuring people out, social referencing emerges around 8-9 months. When a child is faced with an uncertain circumstance or event, such as the presence of a stranger, they will intentionally search for information about how to act from a caregiver. So, if a stranger enters the room, an infant will look to its mother to see what her emotional reaction is. If the mother is happy or neutral, the infant will not become anxious. However, if the mother becomes distressed, the infant will respond in kind. Outside of dealing with strangers, infants will also social reference a parent if they are given an unusual toy to play with. If the parent is pleased with the toy, the child will play with it longer than if the parent is displeased or disgusted.

12.1.2.2. Play and affiliation. Children are also motivated to engage in play. Up to about 1.5 years of age, children play alone called solitary play. Between 1 ½ and 2 years of age, children play side-by-side, doing the same thing or similar things, but not interacting with each other. This is called parallel play. Associative play occurs next and is when two or more children interact with one another by sharing or borrowing toys or materials. They do not do the same thing though. Around 3 years of age, children engage in cooperative play which includes games that involve group imagination such as “playing house.” Finally, onlooker play is an important way for children to participate in games or activities they are not already engaged in. They simply wait for the right moment to jump in and then do so. Though play develops across time, or becomes more complex, solitary play and onlooker play do remain options children reserve for themselves. Sometimes we just want to play a game by ourselves and not have a friend split the screen with us, as in the case of video games and if they are on the couch next to you.

12.1.2.3. Attachment and affiliation, to people and God. Attachment is an emotional bond established between two individuals and involving one’s sense of security. Our attachments during infancy have repercussions on how we relate to others the rest of our lives. Ainsworth et al. (1978) identified three attachment styles an infant possesses. The first is a secure attachment and results in the use of a mother as a home base to explore the world. The child will occasionally return to her. She also becomes upset when she leaves and goes to the mother when she returns. Next is the avoidantly attached child who does not seek closeness with her and avoids the mother after she returns. Finally, is the ambivalent attachment in which the child displays a mixture of positive and negative emotions toward the mother. She remains relatively close to her which limits how much she explores the world. If the mother leaves, the child will seek closeness with the mother all the while kicking and hitting her.

A fourth style has been added due to recent research. This is the disorganized-disoriented attachment style which is characterized by inconsistent, often contradictory behaviors, confusion, and dazed behavior (Main & Solomon, 1990). An example might be the child approaching the mother when she returns, but not making eye contact with her.

The interplay of a caregiver’s parenting style and the child’s subsequent attachment to this parent has long been considered a factor on the psychological health of the person throughout life. For instance, father’s psychological autonomy has been shown to lead to greater academic performance and fewer signs of depression in 4th graders (Mattanah, 2001). Attachment is also important when the child is leaving home for the first time to go to college. Mattanah, Hancock, and Brand (2004) showed in a sample of four hundred four students at a university in the Northeastern United States that separation individuation mediated the link between secure attachment and college adjustment. The nature of adult romantic relationships has been associated with attachment style in infancy (Kirkpatrick, 1997). One final way this appears in adulthood is through a person’s relationship with a god figure.

An extrapolation of attachment research is that we can perceive God’s love for the individual in terms of a mother’s love for her child, but this attachment is not always to God. For instance, Protestants, seeing God as distant, use Jesus to form an attachment relationship while Catholics utilize Mary as their ideal attachment figure. It could be that negative emotions and insecurity in relation to God do not always signify the lack of an attachment relationship, but maybe a different type of pattern or style (Kirkpatrick, 1995). Consider that an abused child still develops an attachment to an abusive mother or father. The same could occur with God and may well explain why images of vindictive and frightening gods have survived through human history.

One important thing to note is that in human relationships, the other person’s actions can affect the relationship, for better or worse. Perceived relationships with God do not have this quality. As God cannot affect us, we cannot affect Him. This allows the person to invent or reinvent the relationship with God in secure terms without allowing counterproductive behaviors to retard progress. Hence, Kirkpatrick (1995) says people “with insecure attachment histories might be able to find in God…the kind of secure attachment relationship they never had in human interpersonal relationships (p. 62).” The best human attachment figures are ultimately fallible while God is not limited by this.

Pargament (1997) defined three styles of attachment to God. First is the ‘secure’ attachment in which God is viewed as warm, receptive, supportive, and protective, and the person is very satisfied with the relationship. Next is the ‘avoidant attachment’ in which God is seen as impersonal, distant, and disinterested, and the person characterizes the relationship as one in which God does not care about him or her. Finally, is the ‘anxious/ambivalent’ attachment. Here, God seems to be inconsistent in His reaction to the person, sometimes warm and receptive and sometimes not. The person is not sure if God loves him or not. We might say that the God of the secure attachment is the authoritative parent, the God of the avoidant attachment is authoritarian, and the God of the anxious/ambivalent attachment is permissive.

Kirkpatrick and Shaver (1990) note that attachment and religion may be linked in important ways. They offer a “compensation hypothesis” which states that insecurely attached individuals are motivated to compensate for the absence of this secure relationship by believing in a loving God. Their study evaluated the self-reports of 213 respondents (180 females and 33 males) and found that the avoidant parent-child attachment relationship yielded greater levels of adult religiousness while those with secure attachment had lower scores. The avoidant respondents were also four times as likely to have experienced a sudden religious conversion.

They also remind the reader that the child uses the attachment figure as a haven and secure base, and go on to note that there is ample evidence to suggest the same function for God. Bereaved persons become more religious, soldiers pray in foxholes, and many who are in emotional distress turn to God. Further, Christianity has a plethora of references to God being by one’s side always and the person having a friend in Jesus.

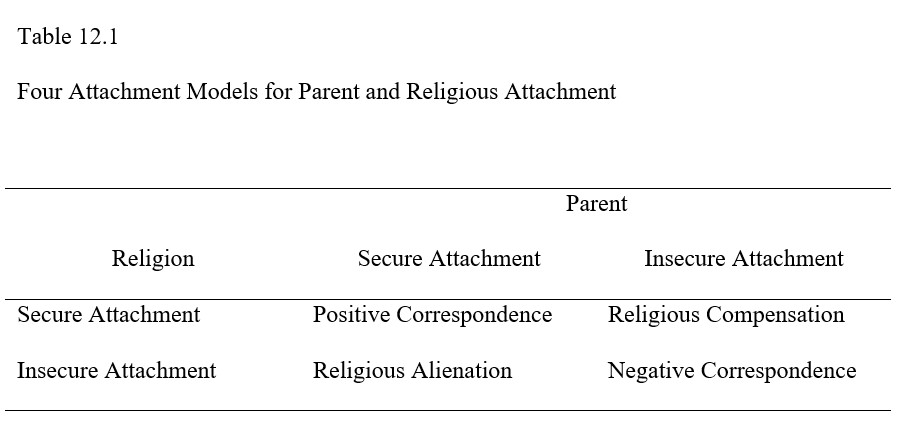

Pargament (1997) expanded upon the compensation hypothesis and showed that the relationship between attachment history and religious beliefs is far from simple. He summarized four relationships between parental and religious attachments extrapolated from Kirkpatrick’s research. First, if a child had a secure attachment to the parent, he may develop a secure attachment to religion, called ‘positive correspondence.’ In this scenario, the result of a loving and trusting relationship with one’s parents is transferred to God as well. This is contrary to the findings of Kirkpatrick and Shaver (1990) which said that securely attached individuals displayed lower levels of religiosity. More in line with their view is Pargament’s second category, secure attachment to parents and insecure attachment to religion, called ‘religious alienation.’ Here the person who had a secure attachment to parents may not feel the need to believe in God. He does not need to compensate for any deficiencies.

The third category is also in line with Kirkpatrick and Shaver’s study. Modeled after their hypothesis, ‘religious compensation’ results from an insecure attachment to parents and a secure attachment to religion. Finally, an insecure attachment to parents may yield an insecure attachment to religion called ‘negative correspondence’ (see Table 12.1). These insecure parental ties have left the person unequipped to build neither strong adult attachments nor a secure spiritual relationship. The person may cling to “false gods” like drug and alcohol addiction, food addiction, religious dogmatism, a religious cult, or a codependent relationship.

12.1.3. Health Factors

“Loneliness kills.” These were the opening words of a March 18, 2015 Time article describing alarming research which shows that loneliness increases the risk of death. How so? According to the meta-analysis of 70 studies published from 1980 to 2014, social isolation increases mortality by 29%, loneliness does so by 26%, and living alone by 32%; but being socially connected leads to higher survival rates (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2015). The authors note, as did Tiwari (2013) earlier, that social isolation and loneliness should be listed as a public health concern as it can lead to poorer health and decreased longevity, as well as CVD (coronary vascular disease; Holt-Lunstad & Smith, 2016). Other ill effects of loneliness include greater stimulated cytokine production due to stress which in turn causes inflammation (Jaremka et al., 2013); greater occurrence of suicidal behavior (Stickley & Koyanagi, 2016); pain, depression, and fatigue (Jarema et al., 2014); and psychotic disorders such as delusional disorders, depressive psychosis, and subjective thought disorder (Badcock et al., 2015).

On a positive note, Stanley, Conwell, Bowen, and Van Orden (2013) found that for older adults who report feeling lonely, owning a pet is one way to feel socially connected. In their study, pet owners were found to be 36% less likely than non-pet owners to report feeling lonely. Those who lived alone and did not own a pet had the greatest odds of reporting loneliness. But the authors offer an admonition – owning a pet, if not managed properly, could actually be deleterious to health. They write, “For example, an older adult may place the well-being of their pet over the safety and health of themselves; they may pay for meals and veterinary services for their pet at the expense of their own meals or healthcare.” Bereavement concerns were also raised, though they say that with careful planning, any negative consequences of owning a pet can be mitigated.

To read the Time article, please visit: http://time.com/3747784/loneliness-mortality/

12.1.4. Social Rejection

Being rejected or ignored by others, called ostracism, hurts. No literally. It hurts. Research by Kross, Berman, Mischel, Smith, and Wager (2011) has shown that when rejected, brain areas such as the secondary somatosensory cortex and dorsal posterior insula which are implicated in the experience of physical pain, become active. So not only are the experiences of physical pain and social rejection distressing, the authors say that they share a common somatosensory representation too.

So, what do you do if you have experienced social rejection? A 2012 article by the American Psychological Association says to seek inclusion elsewhere. Those who have been excluded tend to become more sensitive to opportunities to connect and adjust their behavior as such. They may act more likable, show greater conformity, and comply with the requests of others. Of course, some respond with anger and aggression instead. The article says, “If someone’s primary concern is to reassert a sense of control, he or she may become aggressive as a way to force others to pay attention. Sadly, that can create a downward spiral. When people act aggressively, they’re even less likely to gain social acceptance.” The effects of long-term ostracism can be devastating but non-chronic rejection can be easier to alleviate. Seek out healthy positive connections with both friends and family as a way to combat rejection.

For more on the APA article, see https://www.apa.org/monitor/2012/04/rejection.

12.2. Factors on Attraction

Section Learning Objectives

- Clarify how proximity affects interpersonal attractiveness.

- Clarify how familiarity affects interpersonal attractiveness.

- Clarify how beauty affects interpersonal attractiveness.

- Clarify how similarity affects interpersonal attractiveness.

- Clarify how reciprocity affects interpersonal attractiveness.

- Clarify how playing hard to get affects interpersonal attractiveness.

- Clarify how intimacy affects interpersonal attractiveness.

- Describe mate selection strategies used by men and women.

On April 7, 2015, Psychology Today published an article entitled, The Four Types of Attraction. Referred to as an attraction pyramid, it places status and health at the bottom, emotional in the middle, and logic at the top of the pyramid. Status takes on two forms. Internal refers to confidence, your skills, and what you believe or your values. External refers to your job, visual markers, and what you own such as a nice car or house. The article states that confidence may be particularly important and overrides external status in the long run. Health can include the way you look, move, smell, and your intelligence. The middle level is emotional which includes what makes us unique, trust and comfort, our emotional intelligence, and how mysterious we appear to a potential suitor. And then at the top is logic which helps us to be sure this individual is aligned with us in terms of life goals such as having kids, getting married, where we will live, etc. The article says – “With greater alignment, there is greater attraction.” Since online romance is trending now, the pyramid flips and we focus on logic, then emotion, and then status and health, but meeting in person is important and should be done as soon as possible. This way, we can be sure there is a physical attraction and can only be validated in person.

To read the article for yourself, visit: https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/valley-girl-brain/201504/the-four-types-attraction

So how accurate is the article? We will tackle several factors on attraction to include proximity, familiarity, physical attractiveness, similarity, reciprocity, the hard-to-get effect, and intimacy, and then close with a discussion of mate selection.

12.2.1. Proximity

First, proximity states that the closer two people live to one another, the more likely they are to interact. The more frequent their interaction, the more likely they will like one another then. Is it possible that individuals living in a housing development would strike up friendships while doing chores? This is exactly what Festinger, Schachter, and Back (1950) found in an investigation of 260 married veterans living in a housing project at MIT. Proximity was the primary factor that led to the formation of friendships. For proximity to work, people must be able to engage in face-to-face communication, which is possible when they share a communication space and time (Monge & Kirste, 1980) and proximity is a determinant of interpersonal attraction for both sexes (Allgeier and Byrne, 1972). A more recent study of 40 couples from Punjab, Pakistan provides cross-cultural evidence of the importance of proximity as well. The authors write, “The results of qualitative analysis showed that friends who stated that they share the same room or same town were shown to have higher scores on interpersonal attraction than friends who lived in distant towns and cities” (pg. 145; Batool & Malik, 2010).

12.2.2. Mere Exposure – A Case for Familiarity?

In fact, the more we are exposed to novel stimuli, the greater our liking of them will be, called the mere exposure effect. Across two studies, Saegert, Swap, & Zajonc (1973) found that the more frequently we are exposed to a stimulus, even if it is negative, the greater our liking of it will be, and that this holds true for inanimate objects but also interpersonal attitudes. They conclude, “…the mere repeated exposure of people is a sufficient condition for enhancement of attraction, despite differences in favorability of context, and in the absence of any obvious rewards or punishments by these people” (pg. 241).

Peskin and Newell (2004) present an interesting study investigating how familiarity affects attraction. In their first experiment, participants rated the attractiveness, distinctiveness, and familiarity of 84 monochrome photographs of unfamiliar female faces obtained from US high school yearbooks. The ratings were made by three different groups – 31 participants for the attractiveness rating, 37 for the distinctiveness rating, and 30 for the familiarity rating – and no participant participated in more than one of the studies. In all three rating studies, a 7-point scale was used whereby 1 indicated that the face was not attractive, distinctive, or familiar and 7 indicated that it was very attractive, distinctive, or familiar. They found a significant negative correlation between attractiveness and distinctiveness and a significant positive correlation between attractiveness and familiarity scores, consistent with the literature.

In the second experiment, 32 participants were exposed to 16 of the 24 most typical and 16 of the 24 most distinctive faces from the experiment and the other 8 faces serving as controls. The controls were shown once during the judgment phase while the 16 typical and 16 distinctive faces were shown six times for a total of 192 trials. Ratings of attractiveness were given during the judgment phase. Results showed that repeated exposure increased attractiveness ratings overall, and there was no difference between typical and distinctive faces. These results were found to be due to increased exposure and not judgment bias or experimental conditions since the attractiveness ratings of the 16 control faces were compared to the same faces from experiment 1 and no significant difference between the two groups was found.

Overall, Peskin and Newell (2004) state that their findings show that increasing the familiarity of faces by increasing exposure led to increased attractiveness ratings. They add, “We also demonstrated that typical faces were found to be more attractive than distinctive faces although both face types were subjected to similar increases in familiarity” (pg. 156).

12.2.3. Physical Attractiveness

Second, we choose who we spend time with based on how attractive they are. Attractive people are seen as more interesting, happier, smarter, sensitive, and moral and as such are liked more than less attractive people. This is partly due to the halo effect or when we hold a favorable attitude to traits that are unrelated. We see beauty as a valuable asset and one that can be exchanged for other things during our social interactions. Between personality, social skills, intelligence, and attractiveness, which characteristic do you think matters most in dating? In a field study randomly pairing subjects at a “Computer Dance” the largest determinant of how much a partner was liked, how much he wanted to date the partner again, and how frequently he asked the partner out, was simply the physical attractiveness of the partner (Walster et al., 1966).

In a more contemporary twist on dating and interpersonal attraction, Luo and Zhang (2009) looked at speed dating. Results showed that the biggest predictor of attraction for both males and females was the physical attractiveness of their partner (reciprocity showed some influence though similarity produced no evidence – both will be discussed shortly so keep it in mind for now).

Is beauty linked to a name though? Garwood et al. (1980) asked 197 college students to choose a beauty queen from six photographs, all equivalent in terms of physical attractiveness. Half of the women in the photographs had a desirable first name while the other half did not. Results showed that girls with a desirable first name received 158 votes while those with an undesirable first name received just 39 votes.

So why beauty? Humans display what is called a beauty bias. Struckman-Johnson and Struckman- Johnson (1994) investigated the reaction of 277 male, middle-class, Caucasian college students to a vignette in which they were asked to imagine receiving an uninvited sexual advance from a casual female acquaintance. The vignette displayed different degrees of coercion such as low-touch, moderate-push, high-threat, and very high-weapon. The results showed that men had a more positive reaction to the sexual advance of a female acquaintance who was attractive and who used low or moderate levels of coercion than to an unattractive female.

What about attractiveness in the workplace? Hosoda, Stone-Romero, and Coats (2006) found considerable support for the notion that attractive individuals fare better in employment-related decisions (i.e., hiring and promotions) than unattractive individuals. Although there is a beauty bias, the authors found that its strength has weakened over the past few decades.

12.2.4. Similarity

You have likely heard the expressions “Opposites attract” and “Birds of a feather flock together.” The former expression contradicts the latter, and so this leads us to wonder which is it? Research shows that we are most attracted to people who are like us in terms of our religious and political beliefs, values, appearance, educational background, age, and other demographic variables (Warren, 1966). Thus, we tend to choose people who are similar to us in attitudes and interests as this leads to a more positive evaluation of them. Their agreement with our choices and beliefs helps to reduce any uncertainty we face regarding social situations and improves our understanding of the situation. You might say their similarity also validates our own values, beliefs, and attitudes as they have arrived at the same conclusions that we have. This occurs with identification with sports teams. Our perceived similarity with the group leads to group-derived self-definition more so than the attractiveness of the group such that, “… a team that is “crude, rude, and unattractive” may be appealing to fans who have the same qualities, but repulsive to fans who are more “civilized”.” The authors suggest that sports marketers could emphasize the similarities between fans and their teams (Fisher, 1998). Another form of similarity is in terms of physical attractiveness. According to the matching hypothesis, we date others who are similar to us in terms of how attractive they are (Feingold, 1988; Huston, 1973; Bersheid et al., 1971; Walster, 1970).

12.2.5. Reciprocity

Fourth, we choose people who are likely to engage in a mutual exchange with us. We prefer people who make us feel rewarded and appreciated and in the spirit of reciprocation, we need to give something back to them. This exchange continues so long as both parties regard their interactions to be mutually beneficial or the benefits of the exchange outweigh the costs (Homans, 1961; Thibaut & Kelley, 1959). If you were told that a stranger you interacted with liked you, research shows that you would express a greater liking for that person as well (Aronson & Worchel, 1966) and the same goes for reciprocal desire (Greitmeyer, 2010).

12.2.6. Playing Hard to Get

Does playing hard to get make a woman (or man) more desirable than the one who seems eager for an alliance? Results of five experiments said that it does not though a sixth experiment suggests that if the woman is easy for a particular man to get but hard for all other men to get, she would be preferred over a woman who is uniformly hard or easy to get, or is a woman for which the man has no information about. Men gave these selective women all of the assets (i.e. selective, popular, friendly, warm, and easy going) but none of the liabilities (i.e. problems expected in dating) of the uniformly hard to get and easy to get women. The authors state, “It appears that a woman can intensify her desirability if she acquires a reputation for being hard-to-get and then, by her behavior, makes it clear to a selected romantic partner that she is attracted to him” (pg. 120; Walster et al., 1973). Dai, Dong, and Jia (2014) predicted and found that when person B plays hard to get with person A, this will increase A’s wanting of B but simultaneously decrease A’s liking of B, only if A is psychologically committed to pursuing further relations with B. Otherwise, the hard to get strategy will result in decreased wanting and liking.

12.2.7. Intimacy

Finally, intimacy occurs when we feel close to and trust in another person. This factor is based on the idea of self-disclosure or telling another person about our deepest held secrets, experiences, and beliefs that we do not usually share with others. But this revealing of information comes with the expectation of a mutual self-disclosure from our friend or significant other. We might think that self-disclosure is difficult online but a study of 243 Facebook users shows that we tell our personal secrets on Facebook to those we like and that we feel we can disclose such personal details to people with whom we talk often and come to trust (Sheldon, 2009).

This said, there is a possibility we can overshare, called overdisclosure, which may lead to a reduction in our attractiveness. What if you showed up for class a few minutes early and sat next to one of your classmates who proceeded to give you every detail of their weekend of illicit drug use and sexual activity? This would likely make you feel uncomfortable and seek to move to another seat.

12.2.8. Mate Selection

As you will see in a bit, men and women have vastly different strategies when it comes to selecting a mate. This leads us to ask why, and the answer is rooted in evolutionary psychology. Mate selection occurs universally in all human cultures. In a trend seen around the world, Buss (2004) said that since men can father a nearly unlimited number of children, they favor signs of fertility in women to include being young, attractive, and healthy. Since they also want to know that the child is their own, they favor women who will be sexually faithful to them.

In contrast, women favor a more selective strategy given the incredible time investment having a child involves and the fact that she can only have a limited number of children during her life. She looks for a man who is financially stable and can provide for her children, typically being an older man. In support of the difference in age of a sexual partner pursued by men and women, Buss (1989) found that men wanted to marry women 2.7 years younger while women preferred men 3.4 years older. Also, this finding emerged cross-culturally.

12.3. Types of Relationships

Section Learning Objectives

- Describe how the social exchange theory explains relationships.

- Describe how the equity theory explains relationships.

- List and describe types of relationships.

- Define love and describe its three components according to Sternberg.

- Define jealousy.

12.3.1. Social Exchange Theory

Recall from Section 11.2.9 that social exchange theory is the idea that we utilize a minimax strategy whereby we seek to maximize our rewards all while minimizing our costs. In terms of relationships, those that have less costs and more rewards will be favored, last longer, and be more fulfilling. Rewards include having someone to console us during difficult times, companionship, the experience of love, and having a committed sexual partner for romantic relationships. Costs include the experience of conflict, having to compromise, and needing to sacrifice for another.

12.3.2. Equity Theory

Equity theory (Walster et al., 1978) consists of four propositions. First, it states that individuals will try to maximize outcomes such that rewards win out over punishments. Second, groups will evolve systems for equitably apportioning rewards and punishments among members and members will be expected to adhere to these systems. Those who are equitable to others will be rewarded while those who are not will be punished. Third, individuals in inequitable relationships will experience distress proportional to the inequity. Fourth, those in inequitable relationships will seek to eliminate their distress by restoring equity and will work harder to achieve this the greater the distress they experience. The goal is for all participants to feel they are receiving equal relative gains from the relationship.

According to Hatfield and Traupmann (1981) if an individual feels that the ratio between benefits and costs are disproportionately in favor of the other partner, he or she may feel ripped off or underbenefited, and experience distress. So, what can be done about this? The authors state, “There are only two ways that people can set things right: they can re-establish actual equity or psychological equity. In the first case they can inaugurate real changes in their relationships, e.g. the underbenefited may well ask for more out of their relationships, or their overbenefited partners may offer to try to give more. In the latter case couples may find it harder to change their behavior than to change their minds and so prefer to close their eyes and to reassure themselves that “really, everything is in perfect order”” (pg.168).

12.3.3. Types of Relationships

Relationships can take on a few different forms. In what are called communal relationships, there is an expectation of mutual responsiveness from each member as it relates to tending to member’s needs while exchange relationships involve the expectation of reciprocity in a form of tit-for-tat strategy. This leads to what are called intimate or romantic relationships in which you feel a very strong sense of attraction to another person in terms of their personality and physical features. Love is often a central feature of intimate relationships.

12.3.4. Love

One outcome of this attraction to others, or the need to affiliate/belong is love. What is love? According to a 2011 article in Psychology Today entitled ‘What is Love, and What Isn’t It?’ love is a force of nature, is bigger than we are, inherently free, cannot be turned on as a reward or off as a punishment, cannot be bought, cannot be sold, and cares what becomes of us). Adrian Catron writes in an article entitled, “What is Love? A Philosophy of Life” that “the word love is used as an expression of affection towards someone else….and expresses a human virtue that is based on compassion, affection and kindness.” He goes on to say that love is a practice and you can practice it for the rest of your life. (https://www.huffpost.com/entry/what-is-love-a-philosophy_b_5697322). And finally, the Merriam Webster dictionary online defines love as “strong affection for another arising out of kinship or personal ties” and “attraction based on sexual desire: affection and tenderness felt by lovers.” (Source: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/love).

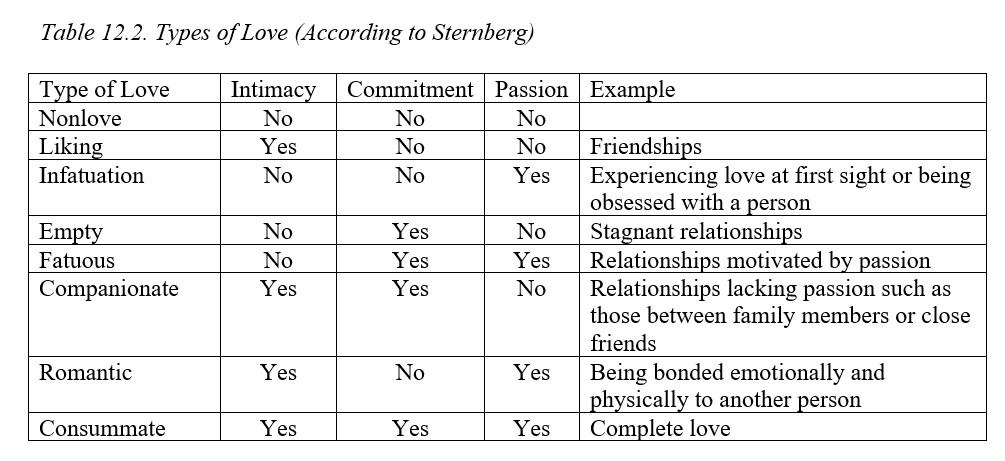

Robert Sternberg (1986) said love is composed of three main parts (called the triangular theory of love): intimacy, commitment, and passion. First, intimacy is the emotional component and involves how much we like, feel close to, and are connected to another person. It grows steadily at first, slows down, and then levels off. Features include holding the person in high regard, sharing personal affect with them, and giving them emotional support in times of need. Second, commitment is the cognitive component and occurs when you decide you truly love the person. You decide to make a long-term commitment to them and as you might expect, is almost non-existent when a relationship begins and is the last to develop usually. If a relationship fails, commitment would show a pattern of declining over time and eventually returns to zero. Third, passion represents the motivational component of love and is the first of the three to develop. It involves attraction, romance, and sex and if a relationship ends, passion can fall to negative levels as the person copes with the loss.

This results in eight subtypes of love which explains differences in the types of love we express. For instance, the love we feel for our significant other will be different than the love we feel for a neighbor or coworker, and reflect different aspects of the components of intimacy, commitment, and passion as follows:

12.3.4.1. Jealousy. The dark side of love is what is called jealousy, or a negative emotional state arising due to a perceived threat to one’s relationship. Take note of the word perceived here. The threat does not have to be real for jealousy to rear its ugly head and what causes men and women to feel jealous varies. For women, a man’s emotional infidelity leads her to fear him leaving and withdrawing his financial support for her offspring, while sexual infidelity is of greater concern to men as he may worry that the children he is supporting are not his own. Jealousy can also arise among siblings who are competing for their parent’s attention, among competitive coworkers especially if a highly desired position is needing to be filled, and among friends. From an evolutionary perspective, jealousy is essential as it helps to preserve social bonds and motivates action to keep important relationships stable and safe. But it can also lead to aggression (Dittman, 2005) and mental health issues.

12.4. Predicting the End of a Relationship

Section Learning Objectives

- Describe Gottman’s Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse.

- Propose antidotes to the horsemen.

- Clarify the importance of forgiveness in relationships.

12.4.1. Communication, Conflict, and Successful Resolution

John Gottman used the metaphor of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse from the New Testament to describe communication styles that can predict the end of a relationship. Though not conquest, war, hunger, and death, Gottman instead used the terms criticism, contempt, defensiveness, and stonewalling. Each will be discussed below, as described on Gottman’s website: https://www.gottman.com/blog/the-four-horsemen-recognizing-criticism-contempt-defensiveness-and-stonewalling/

First, criticism occurs when a person attacks their partner at their core character “or dismantling their whole being” when criticized. An example might be calling them selfish and saying they never think of you. It differs from a complaint which typically involves a specific issue. For instance, one night in March 2019 my wife was stuck at work until after 8pm. I was upset as she did not call to let me know what was going on and we have an agreement to inform one another about changing work schedules. Criticism can become pervasive and when it does, it leads to the other, far deadlier horsemen. “It makes the victim feel assaulted, rejected, and hurt, and often causes the perpetrator and victim to fall into an escalating pattern where the first horseman reappears with greater and greater frequency and intensity, which eventually leads to contempt.”

The second horseman is contempt which involves treating others with disrespect, mocking them, ridiculing, being sarcastic, calling names, or mimicking them. The point is to make the target feel despised and worthless. “Most importantly, contempt is the single greatest predictor of divorce. It must be eliminated.”

Defensiveness is the third horseman and is a response to criticism. When we feel unjustly accused, we have a tendency to make excuses and play the innocent victim to get our partner to back off. Does it work though? “Although it is perfectly understandable to defend yourself if you’re stressed out and feeling attacked, this approach will not have the desired effect. Defensiveness will only escalate the conflict if the critical spouse does not back down or apologize. This is because defensiveness is really a way of blaming your partner, and it won’t allow for healthy conflict management.”

Stonewalling is the fourth horseman and occurs when the listener withdraws from the interaction, shuts down, or stops responding to their partner. They may tune out, act busy, engage in distracting behavior, or turn away and stonewalling is a response to contempt. “It is a result of feeling physiologically flooded, and when we stonewall, we may not even be in a physiological state where we can discuss things rationally.”

Conflict is an unavoidable reality of relationships. The good news is that each horseman has an antidote to stop it. How so?

- To combat criticism, engage in gentle start up. Talk about your feelings using “I” statements and not “you” and express what you need to in a positive way. As the website demonstrates, instead of saying “You always talk about yourself. Why are you always so selfish?” say, “I’m feeling left out of our talk tonight and I need to vent. Can we please talk about my day?”

- To combat contempt, build a culture of appreciation and respect. Regularly express appreciation, gratitude, affection, and respect for your partner. The more positive you are, the less likely that contempt will be expressed. Instead of saying, “You forgot to load the dishwasher again? Ugh. You are so incredibly lazy.” (Rolls eyes.) say, “I understand that you’ve been busy lately, but could you please remember to load the dishwasher when I work late? I’d appreciate it.”

- To combat defensiveness, take responsibility. You can do this for just part of the conflict. A defensive comment might be, “It’s not my fault that we’re going to be late. It’s your fault since you always get dressed at the last second.” Instead, say, “I don’t like being late, but you’re right. We don’t always have to leave so early. I can be a little more flexible.”

- To combat stonewalling, engage in physiological self-soothing. Arguing increases one’s heart rate, releases stress hormones, and activates our flight-fight response. By taking a short break, we can calm down and “return to the discussion in a respectful and rational way.” Failing to take a break could lead to stonewalling and bottling up emotions, or exploding like a volcano at your partner, or both. “So, when you take a break, it should last at least twenty minutes because it will take that long before your body physiologically calms down. It’s crucial that during this time you avoid thoughts of righteous indignation (“I don’t have to take this anymore”) and innocent victimhood (“Why is he always picking on me?”). Spend your time doing something soothing and distracting, like listening to music, reading, or exercising. It doesn’t really matter what you do, as long as it helps you to calm down.”

12.4.2. Forgiveness

According to the Mayo Clinic, forgiveness involves letting go of resentment and any thought we might have about getting revenge on someone for past wrongdoing. So what are the benefits of forgiving others? Our mental health will be better, we will experience less anxiety and stress, we may experience fewer symptoms of depression, our heart will be healthier, we will feel less hostility, and our relationships overall will be healthier.

It’s easy to hold a grudge. Let’s face it, whatever the cause, it likely left us feeling angry, confused, and sad. We may even be bitter not only to the person who slighted us but extend this to others who had nothing to do with the situation. We might have trouble focusing on the present as we dwell on the past and feel like life lacks meaning and purpose.

But even if we are the type of person who holds grudges, we can learn to forgive. The Mayo Clinic offers some useful steps to help us get there. First, we should recognize the value of forgiveness. Next, we should determine what needs healing and who we should forgive and for what. Then we should consider joining a support group or talk with a counselor. Fourth, we need to acknowledge our emotions, the harm they do to us, and how they affect our behavior. We then attempt to release them. Fifth, choose to forgive the person who offended us leading to the final step of moving away from seeing ourselves as the victim and “release the control and power the offending person and situation have had in your life.”

At times, we still cannot forgive the person. They recommend practicing empathy so that we can see the situation from their perspective, praying, reflecting on instances of when you offended another person and they forgave you, and be aware that forgiveness does not happen all at once but is a process.

Read the article by visiting: https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/adult-health/in-depth/forgiveness/art-20047692

Module Recap

That’s it. With the close of this module, we also finish the book. We hope you enjoyed learning about attraction and the various factors on it, types of relationships, and complications we might endure. As we learned, conflict is inevitable in any type of relationship, but there is hope. Never give up or give in.

Module 12 is the last in Part IV: How We Relate to Others.

2nd edition