Learning Objectives

The objectives of this section is to help students …

- Understand the role of distribution channels

- Understand the flows in channels

- Understand the participants in the marketing channel

- Understand their capabilities and limitations

In this chapter, we will look at the basics of channels of distribution. We shall see that several basic functions have emerged that are typically the responsibility of a channel member. Also, it will become clear that channel selection is not a static, once-and-for-all choice, but that it is a dynamic part of marketing planning. As was true for the product, the channel must be managed in order to work. Unlike the product, the channel is composed of individuals and groups that exhibit unique traits that might be in conflict, and that have a constant need to be motivated. These issues will also be addressed. Finally, the institutions or members of the channel will be introduced and discussed.

The dual functions of channels

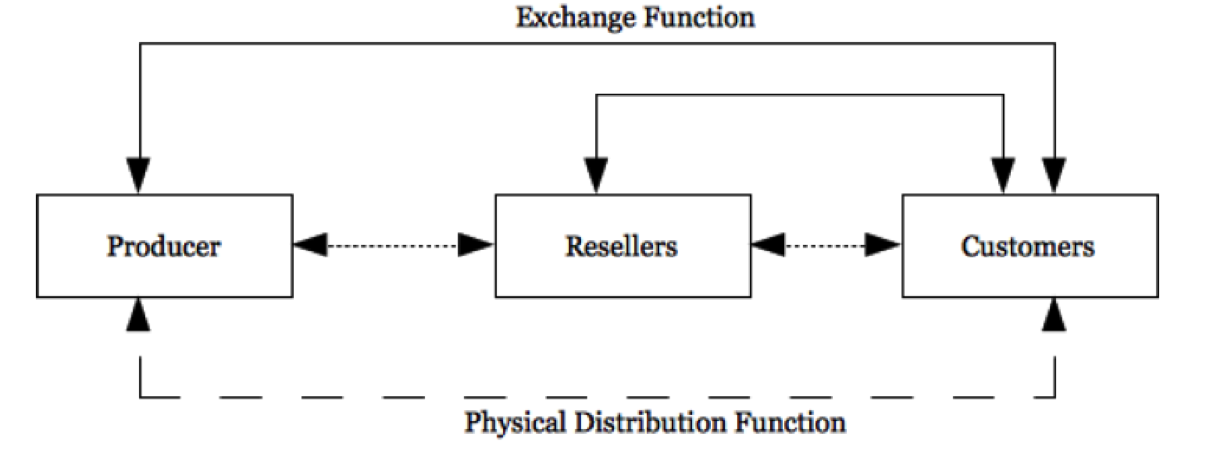

Just as with the other elements of the firm’s marketing program, distribution activities are undertaken to facilitate the exchange between marketers and consumers. There are two basic functions performed between the manufacturer and the ultimate consumer. The first called the exchange function, involves sales of the product to the various members of the channel of distribution. The second, the physical distribution function, moves products through the exchange channel, simultaneously with title and ownership. Decisions concerning both of these sets of activities are made in conjunction with the firm’s overall marketing plan and are designed so that the firm can best serve its customers in the market place. In actuality, without a channel of distribution the exchange process would be far more difficult and ineffective.

The key role that distribution plays is satisfying a firm’s customer and achieving a profit for the firm. From a distribution perspective, customer satisfaction involves maximizing time and place utility to: the organization’s suppliers, intermediate customers, and final customers. In short, organizations attempt to get their products to their customers in the most effective ways. Further, as households find their needs satisfied by an increased quantity and variety of goods, the mechanism of exchange—i.e. the channel—increases in importance.

Figure 10.1: Dual-flow system in marketing channels.

The evolution of the marketing channel

As consumers, we have clearly taken for granted that when we go to a supermarket the shelves will be filled with products we want; when we are thirsty there will be a Coke machine 0r bar around the corner; and, when we do not have time to shop, we can pick-up the telephone and order from the J.C. Penney catalog or through the Internet. Of course, if we give it some thought, we realize that this magic is not a given, and that hundreds of thousands of people plan, organize, and labor long hours so that this modern convenience is available to you, the consumer. It has not always been this way, and it is still not this way in many other countries. Perhaps a little anthropological discussion will help our understanding.

The channel structure in a primitive culture is virtually nonexistent. The family or tribal group is almost entirely self-sufficient. The group is composed of individuals who are both communal producers and consumers of whatever goods and services can be made available. As economies evolve, people begin to specialize in some aspect of economic activity. They engage in farming, hunting, or fishing, or some other basic craft. Eventually this specialized skill produces excess products, which they exchange or trade for needed goods that have been produced by others. This exchange process or barter marks the beginning of formal channels of distribution. These early channels involve a series of exchanges between two parties who are producers of one product and consumers of the other.

With the growth of specialization, particularly industrial specialization, and with improvements in methods of transportation and communication, channels of distribution become longer and more complex. Thus, corn grown in Illinois may be processed into corn chips in West Texas, which are then distributed throughout the United States. Or, turkeys raised in Virginia are sent to New York so that they can be shipped to supermarkets in Virginia. Channels do not always make sense.

The channel mechanism also operates for service products. In the case of medical care, the channel mechanism may consist of a local physician, specialists, hospitals, ambulances, laboratories, insurance companies, physical therapists, home care professionals, and so forth. All of these individuals are interdependent, and could not operate successfully without the cooperation and capabilities of all the others.

Based on this relationship, we define a marketing channel as sets of interdependent organizations involved in the process of making a product or service available for use or consumption, as well as providing a payment mechanism for the provider.

This definition implies several important characteristics of the channel. First, the channel consists of institutions, some under the control of the producer and some outside the producer’s control. Yet all must be recognized, selected, and integrated into an efficient channel arrangement.

Second, the channel management process is continuous and requires continuous monitoring and reappraisal. The channel operates 24 hours a day and exists in an environment where change is the norm.

Finally, channels should have certain distribution objectives guiding their activities. The structure and management of the marketing channel is thus in part a function of a firm’s distribution objective. It is also a part of the marketing objectives, especially the need to make an acceptable profit. Channels usually represent the largest costs in marketing a product.

Flows in marketing channels

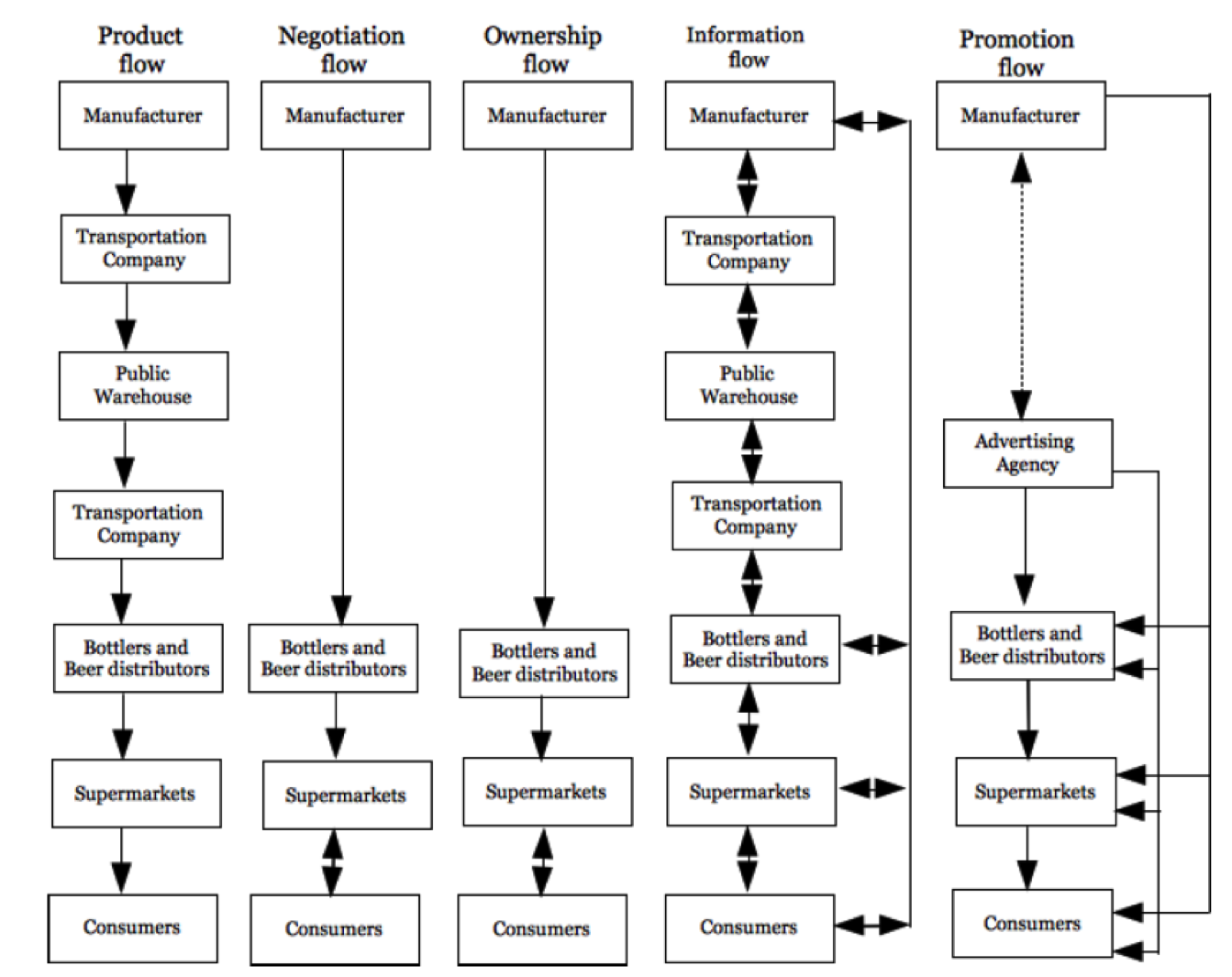

One traditional framework that has been used to express the channel mechanism is the concept of flow. These flows, touched upon in Exhibit 32, reflect the many linkages that tie channel members and other agencies together in the distribution of goods and services. From the perspective of the channel manager, there are five important flows.

- Product flow

- Negotiation flow

- Ownership flow

- Information flow

- Promotion flow

These flows are illustrated for Perrier Water in Figure 10.2.

The product flow refers to the movement of the physical product from the manufacturer through all the parties who take physical possession of the product until it reaches the ultimate consumer. The negotiation flow encompasses the institutions that are associated with the actual exchange processes. The ownership flow shows the movement of title through the channel. Information flow identifies the individuals who participate in the flow of information either up or down the channel. Finally, the promotion flow refers to the flow of persuasive communication in the form of advertising, personal selling, sales promotion, and public relations.

Figure 10.2: Five flows in the marketing channel for Perrier Water. (Source: Bert Rosenbloom, Marketing Channels: A Management View, Dryden Press, Chicago, 1983, p.11.)

Functions of the channel

The primary purpose of any channel of distribution is to bridge the gap between the producer of a product and the user of it, whether the parties are located in the same community or in different countries thousands of miles apart. The channel is composed of different institutions that facilitate the transaction and the physical exchange. Institutions in channels fall into three categories: (a) the producer of the product–a craftsman, manufacturer, farmer, or other extractive industry producer; (b) the user of the product–an individual, household, business buyer, institution, or government; and (c) certain middlemen at the wholesale and/or retail level. Not all channel members perform the same function.

Heskett (2) suggests that a channel performs three important functions:

- Transactional functions: buying, selling, and risk assumption

- Logistical functions: assembly, storage, sorting, and transportation

- Facilitating functions: post-purchase service and maintenance, financing, information dissemination, and channel coordination or leadership

These functions are necessary for the effective flow of product and title to the customer and payment back to the producer. Certain characteristics are implied in every channel. First, although you can eliminate or substitute channel institutions, the functions that these institutions perform cannot be eliminated. Typically, if a wholesaler or a retailer is removed from the channel, the function they perform will be either shifted forward to a retailer or the consumer, or shifted backward to a wholesaler or the manufacturer. For example, a producer of custom hunting knives might decide to sell through direct mail instead of retail outlets. The producer absorbs the sorting, storage, and risk functions; the post office absorbs the transportation function; and the consumer assumes more risk in not being able to touch or try the product before purchase.

Second, all channel institutional members are part of many channel transactions at any given point in time. As a result, the complexity may be quite overwhelming. Consider for the moment how many different products you purchase in a single year, and the vast number of channel mechanisms you use.

Third, the fact that you are able to complete all these transactions to your satisfaction, as well as to the satisfaction of the other channel members, is due to the routinization benefits provided through the channel. Routinization means that the right products are most always found in places (catalogues or stores) where the consumer expects to find them, comparisons are possible, prices are marked, and methods of payment are available. Routinization aids the producer as well as the consumer, in that the producer knows what to make, when to make it, and how many units to make.

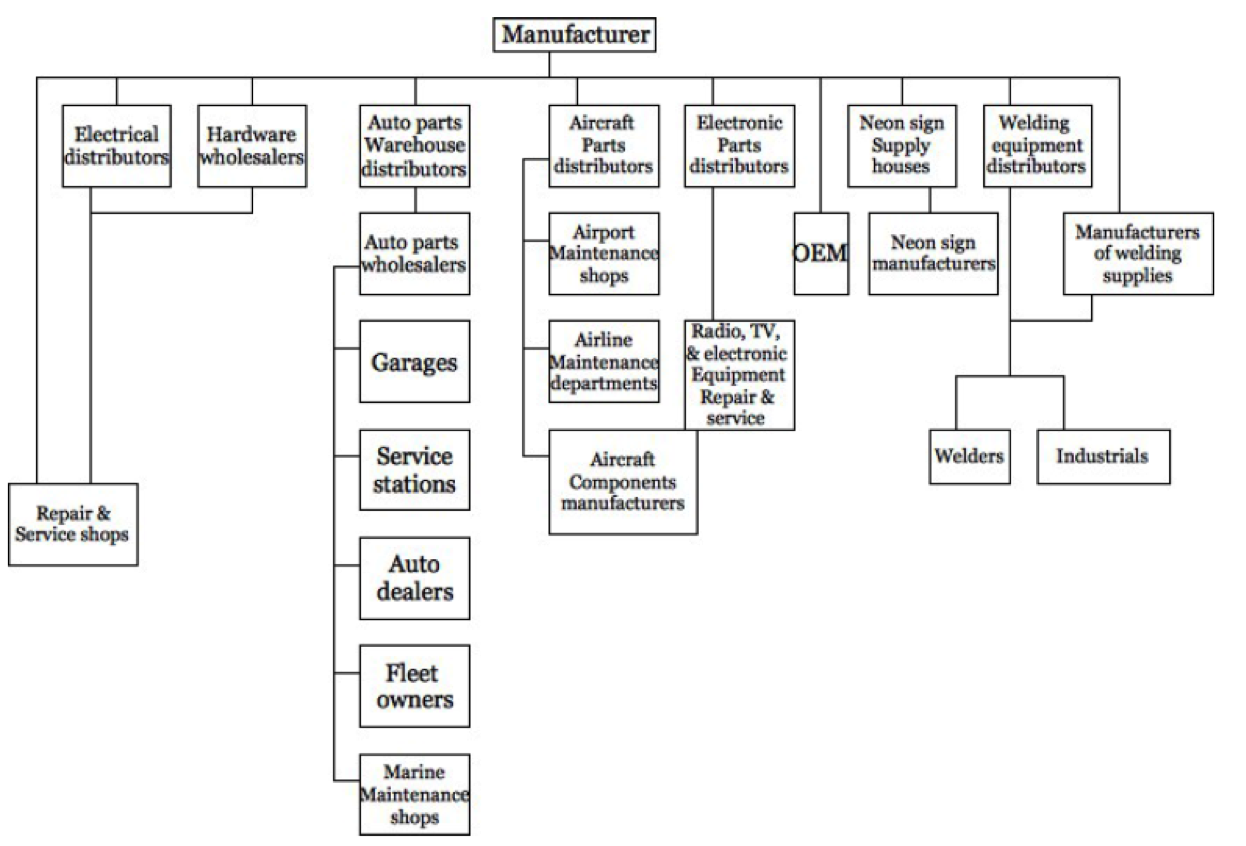

Fourth, there are instances when the best channel arrangement is direct, from the producer to the ultimate user. This is particularly true when available middlemen are incompetent, unavailable, or the producer feels he can perform the tasks better. Similarly, it may be important for the producer to maintain direct contact with customers so that quick and accurate adjustments can be made. Direct-to-user channels are common in industrial settings, as are door-to-door selling and catalogue sales. Indirect channels are more typical and result, for the most part, because producers are not able to perform the tasks provided by middlemen.

Figure 10.3: Marketing channels of a manufacturer of electrical wire and cable. (Source: Edwin H. Lewis, Marketing Electrical Apparatus and Supplies,McGraw-Hill, Inc., 1961, p. 215.)

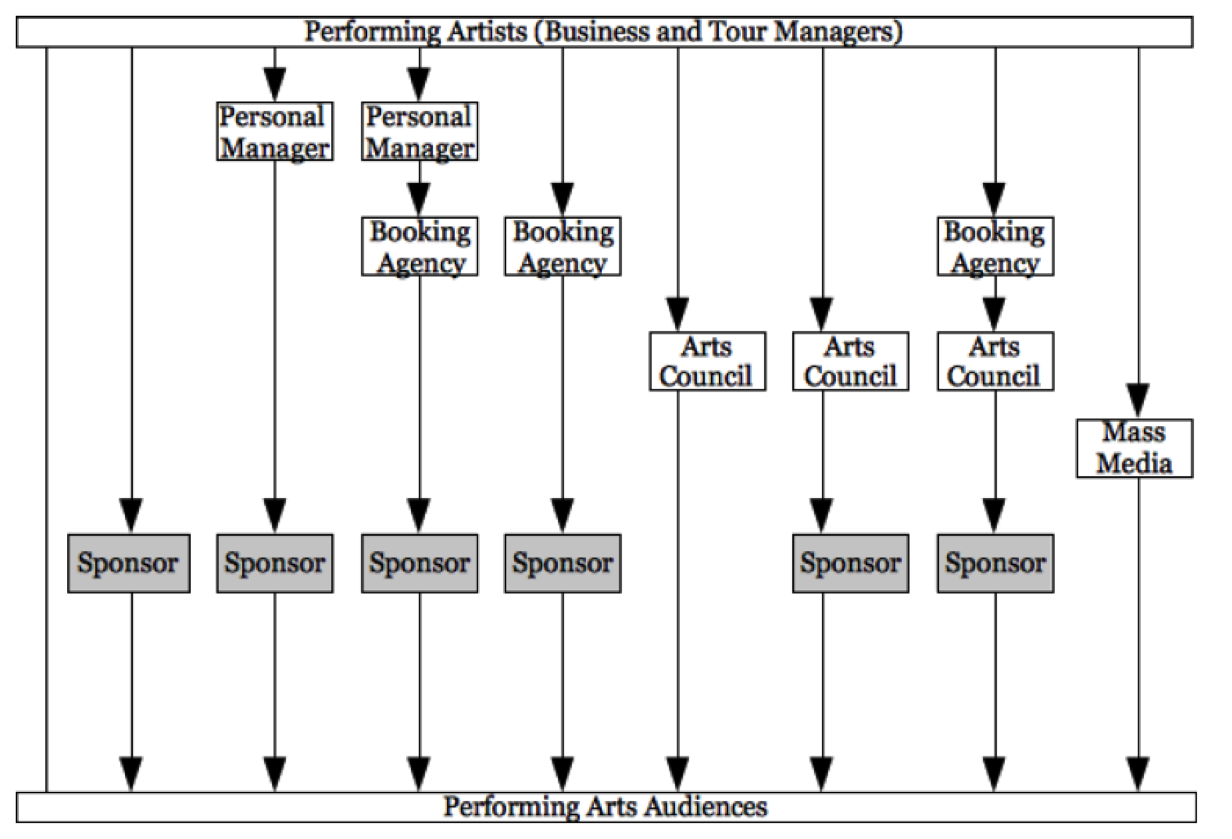

Finally, although the notion of a channel of distribution may sound unlikely for a service product, such as health care or air travel, service marketers also face the problem of delivering their product in the form, at the place and time their customer demands. Banks have responded by developing bank-by-mail, Automatic Teller Machines (ATMs), and other distribution systems. The medical community provides emergency medical vehicles, out patient clinics, 24-hour clinics, and home-care providers. As noted in Figure 10.3 even performing arts employ distribution channels. In all three cases, the industries are attempting to meet the special needs of their target markets while differentiating their product from that of their competition. A channel strategy is evident.

Channel institutions: capabilities and limitations

There are several different types of parties participating in the marketing channel. Some are members, while others are nonmembers. The former perform negotiation functions and participate in negotiation and/or ownership while the latter participants do not.

Producer and manufacturer

These firms extract, grow, or make products. A wide array of products is included, and firms vary in size from a one-person operation to those that employ several thousand people and generate billions in sales. Despite these differences, all are in business to satisfy the needs of markets. In order to do this, these firms must be assured that their products are distributed to their intended markets. Most producing and manufacturing firms are not in a favorable position to perform all the tasks that would be necessary to distribute their products directly to their final user markets. A computer manufacturer may know everything about designing the finest personal computer, but know absolutely nothing about making sure the customer has access to the product.

In many instances, it is the expertise and availability of other channel institutions that make it possible for a producer or manufacturer to even participate in a particular market. Imagine the leverage that a company like Frito-Lay has with various supermarket chains. Suppose you developed a super-tasting new snack chip. What are your chances of taking shelf-facings away from Frito-Lay? Zero. Thankfully, a specialty catalog retailer is able to include your product for a prescribed fee. Likewise, other channel members can be useful to the producer in designing the product, packaging it, pricing it, promoting it, and distributing it through the most effective channels. It is rare that a manufacturer has the expertise found with other channel institutions.

Retailing

Retailing involves all activities required to market consumer goods and services to ultimate consumers who are motivated to buy in order to satisfy individual 0r family needs in contrast to business, institutional, or industrial use. Thus, when an individual buys a computer at Circuit City, groceries at Safeway, or a purse at Ebags.com, a retail sale has been made.

We typically think of a store when we think of a retail sale. However, retail sales are made in ways other than through stores. For example, retail sales are made by door-to-door salespeople, such as an Avon representative, by mail order through a company such as: L.L. Bean, by automatic vending machines, and by hotels and motels. Nevertheless, most retail sales are still made in brick-and-mortar stores.

Figure 10.4: The marketing channels for the performing arts. (Sources: John R. Nevin, “An Empirical Analysis of Marketing Channels for the Performing Arts,” in Michael P. Mokwa, William M. Dawson, and E. Arthur Prieve (eds.). Marketing the Arts, New York: Praeger Publishers, 1980, p. 204.)

The structure of retailing

Stores vary in size, in the kinds of services that are provided, in the assortment of merchandise they carry and in many other respects. Most stores are small and have weekly sales of only a few hundred dollars. A few are extremely large, having sales of USD 500,000 or more on a single day. In fact, on special sale days, some stores have exceeded USD 1 million in sales.

Department stores

Department stores are characterized by their very wide product mixes. That is, they carry many different types of merchandise that may include hardware, clothing, and appliances. Each type of merchandise is typically displayed in a different section or department within the store. The depth of the product mix depends on the store.

Chain stores

The 1920s saw the evolution of the chain store movement. Because chains were so large, they were able to buy a wide variety of merchandise in large quantity discounts. The discounts substantially lowered their cost compared to costs of single unit retailers. As a result, they could set retail prices that were lower than those of their small competitors and thereby increase their share of the market. Furthermore, chains were able to attract many customers because of their convenient locations, made possible by their financial resources and expertise in selecting locations.

Supermarkets

Supermarkets evolved in the 192os and 1930s. For example, Piggly Wiggly Food Stores, founded by Clarence Saunders around 1920, introduced self-service and customer checkout counters. Supermarkets are large, selfservice stores with central checkout facilities, they carry an extensive line of food items and often nonfood products.

Supermarkets were among the first to experiment with such innovations as mass merchandising and low-cost distributed on methods. Their entire approach to the distribution of food and household cleaning and maintenance products was to make available to the public large assortments of a variety of such goods at each store at a minimal price.

Discount houses

Cut-rate retailers have existed for a long time. However, since the end of World War II, the growth of discount houses as a legitimate and extremely competitive retailer has assured this type of outlet a permanent place among retail institutions. It essentially followed the growth of the suburbs.

Discount houses are characterized by an emphasis on price as their main sales appeal. Merchandise assortments are generally broad including both hard and soft goods, but assortments are typically limited to the most popular items, colors, and sizes. Such stores are usually large, self-service operations with long hours, free parking, and relatively simple fixtures.

Warehouse retailing

Warehouse retailing is a relatively new type of retail institution that experienced considerable growth in the 1970s. Catalog showrooms are the largest type of warehouse retailer, at least in terms of the number of stores operated. Retail sales for catalog showrooms grew from USD 1 billion dollars in 1970 to over USD 12 billion today. Their growth rate has slowed recently, but is still substantial.

Franchises

Over the years, particularly since the 1930s, large chain store retailers have posed a serious competitive threat to small storeowners. One of the responses to this threat has been the rapid growth of franchising. Franchising is not a new development. The major oil companies such as Mobil have long enfranchised its dealers, who only sell the products of the franchiser (the oil companies). Automobile manufacturers also enfranchise their dealers, who sell a stipulated make of car (e.g. Chevrolet) and operate their business to some extent as the manufacturer wishes.

Planned shopping centers/malls

After World War II, the United States underwent many changes. Among those most influential on retailing were the growth of the population and of the economy. New highway construction enabled people to leave the congested central cities and move to newly developed suburban residential communities. This movement to the suburbs established the need for new centers of retailing to serve the exploding populations. By 1960 there were 4,500 such centers with both chains and nonchains vying for locations.

Such regional shopping centers are successful because they provide customers with a wide assortment of products. If you want to buy a suit or a dress, a regional shopping center pr0vides many alternatives in one location. Regional centers are those larger centers that typically have one or more department stores as major tenants. Community centers are moderately sized with perhaps a junior department store; while neighborhood centers are small, with the key store usually a supermarket. Local clusters are shopping districts that have simply grown over time around key intersections, courthouses, and the like. String street locations are along major traffic routes, while isolated locations are freestanding sites not necessarily in heavy traffic areas. Stores in isolated locations must use promotion or some other aspect of their marketing mix to attract shoppers. Still, as indicated in the next Newsline, malls are facing serious problems.

Newsline: The mall: a thing of the past?

She was born into retail royalty, a double-decker shrine to capitalism that seduced cool customers and wild-eyed shopaholics alike to roam her exhausting mix of 200 stores. Her funky, W-shaped design was pure 1960s, as if dreamed up by that era’s noted architectural whiz, Mike Brady. When her doors opened the first morning, a brass band serenaded the arriving mob.

Cinderella City, once the biggest covered malls on the planet, was a very big deal–for about six years, until the next gleaming mall came along in 1974. That’s when the music stopped at Cinderella City. Soon the patrons grew scarce, the concrete began crumbling and graffiti stained some of the walls. It’s not pretty, but that’s the cold law of the consumer jungle. One minute you’re luring shoppers from miles around to chug an Orange Julius or grab a snack at the Pretzel Hut; a few years go by, and they’re planting you in the dreaded mall graveyard.

Back then, people made a day out of wandering the massive concourses and lunching in the food courts. Today, with less free time available for many people, shopping is seen as a necessity. Spending time with your family and at home is more important than spending time in a store.

The newest malls reflect the modern need for shopping speed. Covered shopping centers now come equipped with dozens of doors to the outside instead of two main entrances that usher crowds in and out through the anchor department store. That same trend paved the way for the flurry of freestanding Home Depots and TJ Maxx stores as well as discount giants like Wal-Mart. All are sapping customers from mid-market malls, already struggling. In addition to the fresh success of freestanding discount stores, the Internet is drawing off even more customers who seek to buy books or music online.

For the mall to survive, they’ll have to be something different–a high-quality environment for the delivery of high touch, high experience, high margin retail goods and services: a place you go for the entertainment shopping experience. (37)

Nonstore retailing

Nonstore retailing describes sales made to ultimate consumers outside of a traditional retail store setting. In total, nonstore retailing accounts for a relatively small percentage of total retail sales, but it is growing and very important with certain types of merchandise, such as life insurance, cigarettes, magazines, books, CDs, and clothing.

One type of nonstore retailing used by such companies as Avon, Electrolux, and many insurance agencies is inhome selling. Such sales calls may be made to preselected prospects or in some cases on a cold call basis. A variation of door-to-door selling is the demonstration party. Here one customer acts as a host and invites friends. Tupperware has been very successful with this approach.

Vending machines are another type of nonstore retailing. Automated vending uses coin-operated, self-service machines to make a wide variety of products and services available to shoppers in convenient locations. Cigarettes, soft drinks, hosiery, and banking transactions are but a few of the items distributed in this way. This method of retailing is an efficient way to provide continuous; service. It is particularly useful with convenience goods.

Mail order is a form of nonstore retailing that relies on product description to sell merchandise. The communication with the customer can be by flyer or catalog. Magazines, CDs, clothing, and assorted household items are often sold in this fashion. As with vending machines, mail order offers convenience but limited service. It is an efficient way to cover a very large geographical area when shoppers are not concentrated in one location. Many retailers are moving toward the use of newer communications and computer technology in catalog shopping.

Online marketing has emerged during the last decade; it requires that both the retailer and the consumer have computer and modem. A modem connects the computer to a telephone line so that the computer user can reach various online information services. There are two types of online channels: (a) commercial online channels— various companies have set up online information and marketing services that can be assessed by those who have signed up and paid a monthly fee, and (b) Internet—a global web of some 45,000 computer networks that is making instantaneous and decentralized global communication possible. Users can send e-mail, exchange views, shop for products, and access real-time news.

Marketers can carry on online marketing in four ways: (a) using e-mail; (b) participating in forums, newsgroups, and bulletin boards; (c) placing ads online; and (d) creating an electronic storefront. The last two options represent alternative forms of retailing. Today, more than 40,000 businesses have established a home page on the Internet, many of which serve as electronic storefronts. One can order clothing from Lands’ End or J.C. Penney, books from B. Dalton or Amazon.com, or flowers from Lehrer’s Flowers to be sent anywhere in the world. Essentially, a company can open its own store on the Internet.

Companies and individuals can place ads on commercial online services in three different ways. First, the major commercial online services offer an ad section for listing classified ads; the ads are listed according to when they arrived, with the latest ones heading the list. Second, ads can be placed in certain online newsgroups that are basically set up for commercial purposes. Finally, ads can also be put on online billboards; they pop up while subscribers are using the service, even though they did not request an ad.

Catalog marketing occurs when companies mail one or more product catalogs to selected addresses that have a high likelihood of placing an order. Catalogs are sent by huge general-merchandise retailers–J.C. Penney’s, Spiegel–that carry a full line of merchandise. Specialty department stores such as Neiman-Marcus and Saks Fifth Avenue send catalogs to cultivate an upper-middle class market for high-priced, sometimes exotic merchandise.

Integrated marketing

The death of retailing greatly exaggerated

Recently, the MIT economist Lester Thurow suggested that e-commerce could mean the end of 5,000 years of conventional retailing if online stores can combine price advantages with a pleasant virtual shopping experience. Let’s face it: the growth of malls and megastores have shown that people want selection, convenience, and low prices, and that’s about it. Sure, people say they would rather shop from the mom-and-pop on Main Street. But if the junk chain store out on the highway has those curling irons for a dollar less, guess where people go?

So a few years into the e-commerce revolution, here are a few observations and predictions:

- Online stores need to become easier to use as well as completely trustworthy.

- If people can go online and get exactly what they get from retail stores for less money, that is precisely what they will do.

- Some stores will have a kind of invulnerability to online competition; i.e. stores that sell last minute items or specialty items that you have to see.

- Retail stores may improve their chances by becoming more multidimensional; i.e. they have to be fun to visit.

- Still, not everything is rosy for e-tailers. Research provides the following insights:

- For net upstarts, the cost per new customer is USD 82, compared to USD 31 for traditional retailers.

- E-tailers customer satisfaction levels were: 41 per cent for customer service; 51 per cent for easy returns; 57 per cent for better product information; 66 per cent for product selection; 70 per cent for price, and 74 per cent for ease of use.

- Repeat buyers for e-tailers was 21 per cent compared to 34 per cent for traditional retailers.

Suggstions to improve the plight of e-tailers include the following :

- Keep it simple.

- Think like your customer.

- Engage in creative marketing

- Don’t blow everything on advertising.

- Don’t undercut prices.

While all this advice is good, the recent roller coaster ride of high-tech stocks and its disappointing results for e-tailers has completely changed the future of e-tailing. While e-tailers have spent about USD 2 billion industry-wide on advertising campaigns, they often devote far less attention and capital to the quality of services their prospective customers receive once they arrive on site. Etailers are learning what brick and mortar retailers have known all along, that success is less about building market share than about satisfying and retaining customers who can generate substantial profits. (38)

Several major corporations have also acquired or developed mail-order divisions via catalogs. Using catalogs, Avon sells women’s apparel, W.R. Grace sells cheese, and General Mills sells sport shirts.

Some companies have designed “customer-order placing machines”, i.e. kiosks (in contrast to vending machines, which dispense actual products), and placed them in stores, airports, and other locations. For example, the Florsheim Shoe Company includes a machine in several of its stores in which the customer indicates the type of shoe he wants (e.g. dress, sport), and the color and size. Pictures of Florsheim shoes that meet his criteria appear on the screen.

Wholesaling

Another important channel member in many distribution systems is the wholesaler. Wholesaling includes all activities required to market goods and services to businesses, institutions, or industrial users who are motivated to buy for resale or to produce and market other products and services. When a bank buys a new computer for data processing, a school buys audio-visual equipment for classroom use, or a dress shop buys dresses for resale, a wholesale transaction has taken place.

The vast majority of all goods produced in an advanced economy have wholesaling involved in their marketing. This includes manufacturers. who operate sales offices to perform wholesale functions, and retailers, who operate warehouses or otherwise engage in wholesale activities. Even the centrally planned socialist economy needs a structure to handle the movement of goods from the point of production to other product activities or to retailers who distribute to ultimate consumers. Note that many establishments that perform wholesale functions also engage in manufacturing or retailing. This makes it very difficult to produce accurate measures of the extent of wholesale activity. For purposes of keeping statistics, the Bureau of the Census of the United States Department of Commerce defines wholesaling in terms of the per cent of business done by establishments who are primary wholesalers. It is estimated that only about 60 per cent of all wholesale activity is accounted for in this way.

Today there are approximately 600,000 wholesale establishments in the United States, compared to just fewer than 3 million retailers. These 600,000 wholesalers generate a total volume of over USD 1.3 trillion annually; this is approximately 75 per cent greater than the total volume of all retailers. Wholesale volume is greater because it includes sales to industrial users as well as merchandise sold to retailers for resale.

Functions of the wholesaler

- Wholesalers perform a number of useful functions within the channel of distributions. These may include all or some combination of the following:

- Warehousing–the receiving, storage, packaging, and the like necessary to maintain a stock of goods for the customers they service.

- Inventory control and order processing–keeping track of the physical inventory, managing its composition and level, and processing transactions to insure a smooth flow of merchandise from producers to buyers and payment back to the producers.

- Transportation–arranging the physical movement of merchandise.

- Information–supplying information about markets to producers and information about products and suppliers to buyers.

- Selling–personal contact with buyers to sell products and service.

In addition, the wholesaler must perform all the activities necessary for the operation of any other business such as planning, financing, and developing a marketing mix. The five functions listed previously emphasize the nature of wholesaling as a link between the producer and the organizational buyer.

By providing this linkage, wholesales assist both the producer and the buyer. From the buyer’s perspective, the wholesaler typically brings together a wide assortment of products and lessens the need to deal directly with a large number of producers. This makes the buying task much more convenient. A hardware store with thousands of items from hundreds of different producers may find it more efficient to deal with a small number of wholesalers. The wholesaler may also have an inventory in the local market, thus speeding delivery and improving service. The wholesaler assists the producer by making products more accessible to buyers. They provide the producer with wide market coverage information about local market trends in an efficient manner. Wholesalers may also help with the promotion of a producer’s products to a local or regional market via advertising or a sales force to call on organizational buyers.

Types of wholesalers

There are many different types of wholesalers. Some are independent; others are part of a vertical marketing system. Some provide a full range of services; others offer very specialized services. Different wants and needs on the part of both buyers and producers have led to a wide variety of modern wholesalers. Table 13 provides a summary of general types. Wholesaling activities cannot be eliminated, but they can be assumed by manufacturers and retailers. Those merchant wholesalers who have remained viable have done so by providing improved service to suppliers and buyers. To do this at low cost, modern technologies must be increasingly integrated into the wholesale operation.

Table 10.1: Types of modern wholesalers

| Type | Definition | Subcategories |

| Full-service merchandise wholesaler | Take title to the merchandise and assume the risk involved in an independent operation; buy and resell products; offer a complete range of services. | General

Limited-line |

| Limited-service merchant wholesalers | Take title to the merchandise and assume the risk involved in an independent operation; buy and resell products; offer a limited range of services. | Cash and carry

Rack jobbers Drop shippers Mail orders |

| Agents and brokers | Do not take title to the merchandise; bring buyers and sellers together and negotiate the terms of the transaction: agents merchants represent either the buyer or seller, usually on a permanent basis; brokers bring parties together on a temporary basis. | Agents

Buying agents Selling agents Commission merchants Manufacturers’ agents Brokers Real estate Food Other products |

| Manufacturer’s sales | Owned directly by the manufacturers; performs wholesaling functions for the manufacturer. | |

| Facilitator | Perform some specialized functions such as finance or warehousing; to facilitate the wholesale transactions; may be independent or owned by producer or buyer. | Warehouses

Finance companies Transportation companies Trade marts |

Physical distribution

In a society such as ours, the task of physically moving, handling and storing products has become the responsibility of marketing. In fact, to an individual firm operating in a high level economy, these logistical activities are critical. They often represent the only cost saving area open to the firm. Likewise, in markets where product distinctiveness has been reduced greatly, the ability to excel in physical distribution activities may provide a true competitive advantage. Ultimately, physical distribution activities provide the bridge between the production activities and the markets that are spatially and temporally separated.

Physical distribution management may be defined as the process of strategically managing the movement and storage of materials, parts, and finished inventory from suppliers, between enterprise facilities, and to customers. Physical distribution activities include those undertaken to move finished products from the end of the production line to the final consumer. They also include the movement of raw materials from a source of supply to the beginning of the production line, and the movement of parts, etc. to maintain the existing product. Finally, it may include a network for moving the product back to the producer or reseller, as in the case of recalls or repair.

Before discussing physical distribution, it is important to recognize that physical distribution and the channel of distribution are not independent decision areas. They must be considered together in order to achieve the organization’s goal of satisfied customers. Several relationships exist between physical distribution and channels, including the following:

- Defining the physical distribution standards that channel members want.

- Making sure the proposed physical distribution program designed by an organization meets the standards of channel members.

- Selling channel members on physical distribution programs.

- Monitoring the results of the physical distribution program once it has been implemented.

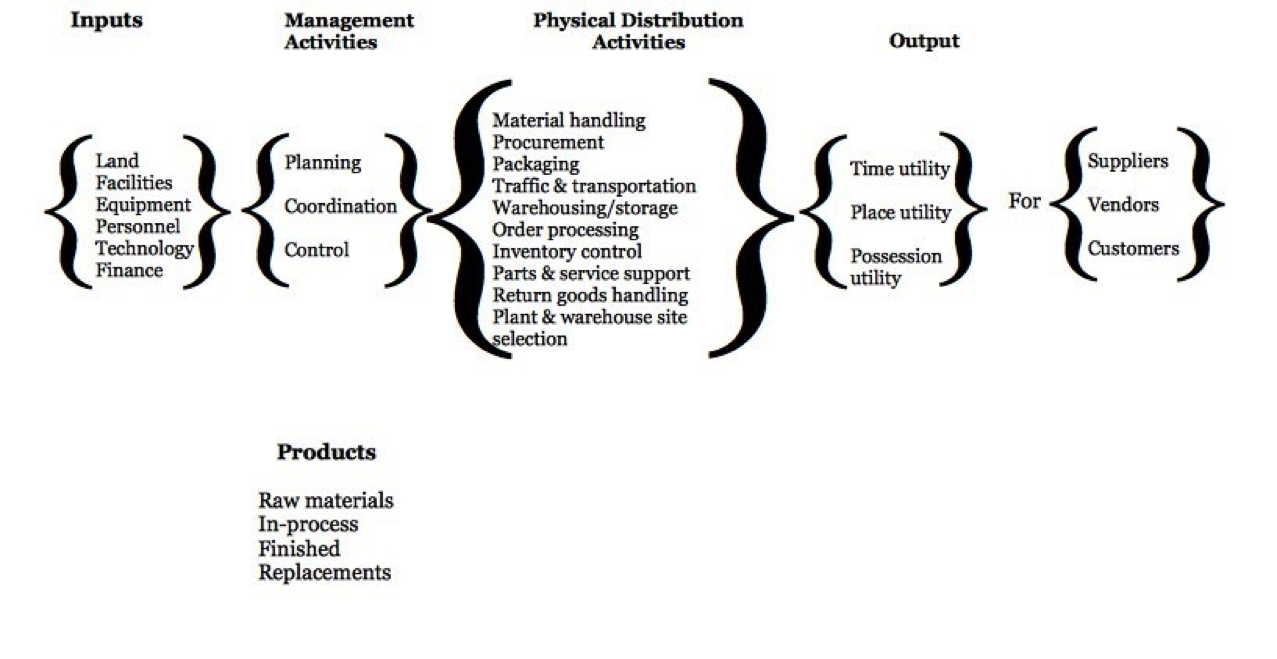

Figure 10.5: The physical distribution management process

As you can see in Figure 10.5 successful management of the flow of goods from a source of supply (raw materials) to the final customer involves effective planning, implementation, and control of many distribution activities. These involve raw material, in-process inventories (partially completed products not ready for resale), and finished products. Effective physical distribution management results initially in the addition of time, place, and possession utility of products; and ultimately, the efficient movement of products to customer and the enhancement of the firm’s marketing efforts.

Physical distribution represents both a cost component and a marketing tool for the purpose of stimulating customer demand. The major costs of physical distribution include transportation, warehousing, carrying inventory, receiving and shipping, packaging, administration, and order processing. The total cost of physical distribution activities represents 13.6 per cent for reseller companies. Poorly managed physical distribution results in excessively high costs, but substantial savings can occur via proper management.

Physical distribution also represents a valuable marketing tool to stimulate consumer demand. Physical distribution improvements that lower prices or provide better service are attractive to potential customers. Similarly, if finished products are not supplied at the right time or in the right places, firms run the risk of losing customers.

SOURCES:

(36): Murra Raphel, “Up Against the Wal-Mart,” Direct Marketing, April 1999, pp. 82-84; Adrienne Sanders, “Yankee Imperialists,” Forbes December 13,1999, p. 36; Jack Neff, “Wal-mart Stores Go Private (Label),” Advertising Age, November 29,1999, pp. 1, 34, 36; Alice Z. Cuneo, “Wal-Mart’s Goal: To Reign Over Web,” Advertising Age, July 5 1999, pp. 1, 27.

(37): Herb Greenberg, “Dead Mall Walking,” Fortune, July 8, 2000, p. 304; Calmetla Y. Coleman, “Making Malls (Gasp!) Convenient,” The Wall Street Journal, February 8 , 2000, pp. B 1, B2; Bill Briggs. “Birth and Death of the American Mall,” The Denver Post, June 4, 2000, pp. D1 D4.

(38): Heather Green, “Shake Out E- Tailers,” Business Week, May 15, 2000, pp. 103-106; Ellen Neubome, “It’s the Service, Stupid,” Business Week, April 3. 2000. p. E8; Chris Ott; “Will Online Shopping Kill Traditional Retail?” The Denver Business Journal, Oct. 28. 1999, p. 46A; Steve Caulk, “Online Merchants Need More Effective Web Sites,” Rocky Mountain News. Thursday, March 8. 2001 , p. 5B.