Case: United States Domestic Automaker, Ford

Nowhere are the effects of globalization seen more drastically than in the automobile industry, especially for the United States “Big 3” automakers: General Motors, Chrysler, and Ford.

Ford’s history dates back to the Model T created by Henry Ford, with the goal of building a car for every family. Today, Ford is in dire competition with not only their domestic competitors, but also now foreign car manufacturers such as Toyota, Volkswagen and Hyundai.

At the current pace, the automotive market is approaching a 50/50 split between United States and overseas-based control of the US market. As a result, Ford is challenged to constantly reevaluate and revamp its market strategy. This is evident, as Ford decided that it was more cost-effective to buy existing networks than to start from scratch, by bringing Jaguar, Volvo, Mazda, Aston Martin and Land Rover under its control. However, Ford has recently decided to sell its stake in both Jaguar and Land Rover to the Indian automaker, Tata, and may divest other divisions as well.

Today, Ford faces a number of important questions. As the globalization of the auto industry continues, how should Ford market its vehicles? What target markets should Ford appeal to? How can it continue to improve production and quality and adhere to the needs of even more demanding customers? And, how should Ford position itself, as a company, in the face of formidable competition?

While the future of Ford is uncertain, one thing is clear, globalization will continue to affect the way domestic and foreign companies do business.

Globalization is difficult to define because it has many dimensions—economic, political, cultural and environmental. The focus here is on the economic dimension of globalization. Economic globalization refers to the “quickly rising share of economic activity in the world [that] seems to be taking place between people in different countries”1 More specifically, economic globalization is the result of the increasing integration of economies around the world, particularly through trade and financial flows and the movement of people and knowledge across international borders.2

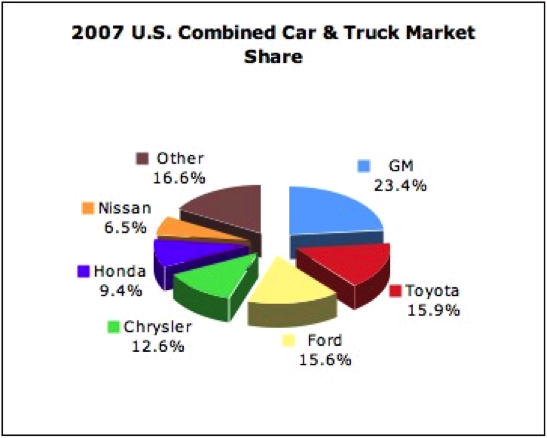

Global Market Share, 2007-20083

As this figure suggests, the “Big Three” must adapt to changes in the market and globalization factors to remain key players in the automotive market. At one point in 2007, for the first time in history, US automaker’s share of their home market fell below 50 percent.

Elements of economic globalization

The growth in cross-border economic activities takes five principal forms: (1) international trade; (2) foreign direct investment; (3) capital market flows; (4) migration (movement of labor); and (5) diffusion of technology.4

International trade: An increasing share of spending on goods and services is devoted to imports and an increasing share of what countries produce is sold as exports. Between 1990 and 2001, the percentage of exports and imports in total economic output (GDP) rose from 32.3 per cent to 37.9 per cent in industrialized countries, and from 33.8 per cent to 48.9 per cent in low and middle-income countries.5 In the 1980s, about 20 per cent of industrialized countries’ exports went to less industrialized countries; today, this share has risen to about 25 per cent, and it appears likely to exceed 33 per cent by 2010.6

The importance of International trade lies at the root of a country’s economy. In the constant changing business market, countries are now more interdependent than ever on their partners for exporting, importing, thereby keeping the home country’s economy afloat and healthy. For example, China’s economy is heavily dependent on the exportation of goods to the United States, and the United States customer base who will buy these products.

Foreign Direct Investment (FDI): According to the United Nations, FDI is defined as “investment made to acquire lasting interest in enterprises operating outside of the economy of the investor”.

Direct investment in constructing production facilities, is distinguished from portfolio investment, which can take the form of short-term capital flows (e.g. loans), or long-term capital flows (e.g. bonds).7 Since 1980, global flows of foreign direct investment have more than doubled relative to GDP.8

Capital market flows: In many countries, particularly in the developed world, investors have increasingly diversified their portfolios to include foreign financial assets, such as international bonds, stocks or mutual funds, and borrowers have increasingly turned to foreign sources of funds.9 Capital market flows also include remittances from migration, which typically flow from industrialized to less industrialized countries. In essence, the entrepreneur has a number of sources for funding a business.

Migration: Whether it is physicians who emigrate from India and Pakistan to Great Britain or seasonal farm workers emigrating from Mexico to the United States, labor is increasingly mobile. Migration can benefit developing economies when migrants who acquired education and know-how abroad return home to establish new enterprises. However, migration can also hurt the economy through “brain drain”, the loss of skilled workers who are essential for economic growth.10

Diffusion of technology: Innovations in telecommunications, information technology, and computing have lowered communication costs and facilitated the cross-border flow of ideas, including technical knowledge as well as more fundamental concepts such as democracy and free markets.11 The rapid growth and adoption of information technology, however, is not evenly distributed around the world—this gap between the information technology is often referred to as the “digital divide”.

As a result, for less industrialized countries this means it is more difficult to advance their businesses without the technical system and knowledge in place such as the Internet, data tracking, and technical resources already existing in many industrialized countries.

Negative effects of globalization for developing country business

Critics of global economic integration warn that:12

- the growth of international trade is exacerbating income inequalities, both between and within industrialized and less industrialized nations

- global commerce is increasingly dominated by transnational corporations which seek to maximize profits without regard for the development needs of individual countries or the local populations

- protectionist policies in industrialized countries prevent many producers in the Third World from accessing export markets;

- the volume and volatility of capital flows increases the risks of banking and currency crises, especially in countries with weak financial institutions

- competition among developing countries to attract foreign investment leads to a “race to the bottom” in which countries dangerously lower environmental standards

- cultural uniqueness is lost in favor of homogenization and a “universal culture” that draws heavily from American culture

Critics of economic integration often point to Latin America as an example where increased openness to international trade had a negative economic effect. Many governments in Latin America (e.g. Peru) liberalized imports far more rapidly than in other regions. In much of Latin America, import liberalization has been credited with increasing the number of people living below the USD $1 a day poverty line and has perpetuated already existing inequalities.13

Positive effects of globalization for developing country business

Conversely, globalization can create new opportunities, new ideas, and open new markets that an entrepreneur may have not had in their home country. As a result, there are a number of positives associated with globalization:

- it creates greater opportunities for firms in less industrialized countries to tap into more and larger markets around the world

- this can lead to more access to capital flows, technology, human capital, cheaper imports and larger export markets

- it allows businesses in less industrialized countries to become part of international production networks and supply chains that are the main conduits of trade

For example, the experience of the East Asian economies demonstrates the positive effect of globalization on economic growth and shows that at least under some circumstances globalization decreases poverty. The spectacular growth in East Asia, which increased GDP per capita by eightfold and raised millions of people out of poverty, was based largely on globalization—export-led growth and closing the technology gap with industrialized countries.14 Generally, economies that globalize have higher growth rates than non-globalizers.15

Also, the role of developing country firms in the value chain is becoming increasingly sophisticated as these firms expand beyond manufacturing into services. For example, it is now commonplace for businesses in industrialized countries to outsource functions such as data processing, customer service and reading x-rays to India and other less industrialized countries.16 Advanced telecommunications and the Internet are facilitating the transfer of these service jobs from industrialized to less industrialized and making it easier and cheaper for less industrialized country firms to enter global markets. In addition to bringing in capital, outsourcing helps prevent “brain drain” because skilled workers may choose to remain in their home country rather than having to migrate to an industrialized country to find work.

Further, some of the allegations made by critics of globalization are very much in dispute—for example, that globalization necessarily leads to growing income inequality or harm to the environment. While there are some countries in which economic integration has led to increased inequality—China, for instance—there is no worldwide trend.17 With regard to the environment, international trade and foreign direct investment can provide less industrialized countries with the incentive to adopt, and the access to, new technologies that may be more ecologically sound. 18 Transnational corporations may also help the environment by exporting higher standards and best practices to less industrialized countries.

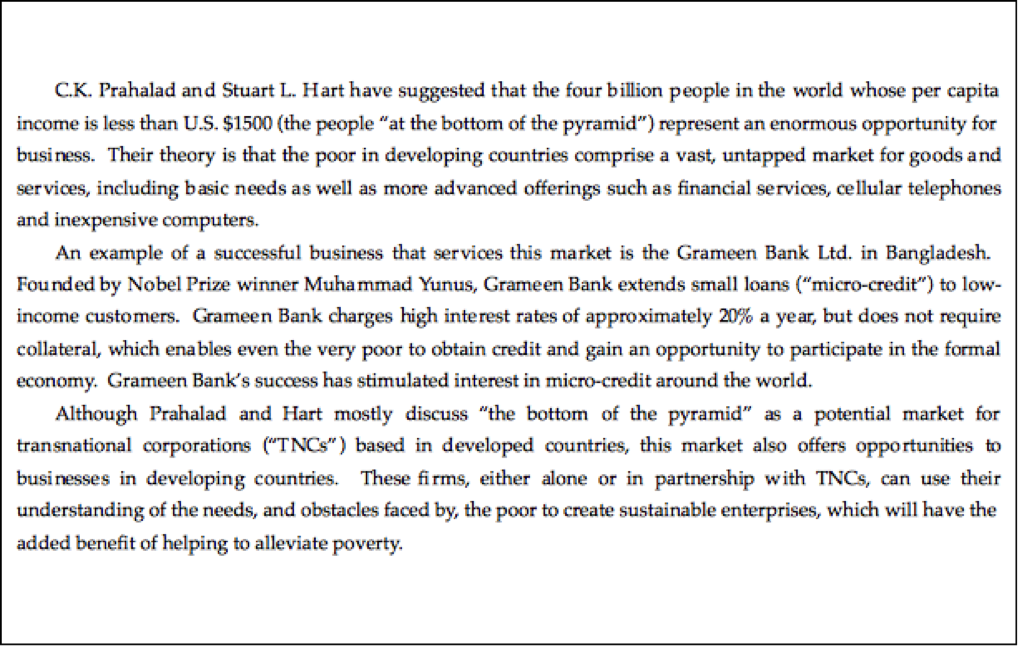

The fortune at the bottom of the pyramid19

REFERENCES

1. World Bank Briefing Paper, 2001

2. IMF Issue Brief, 2000

3. Edmunds.com, 2007

4. Stiglitz, 2003

5. World Briefing Paper, 2001

6. Qureshi, 1996

7. Stiglitz, 2003

8. World Briefing Paper, 2001

9. World Briefing, Paper, 2001

10. Stiglitz, 2003

11. Stiglitz, 2003

12. Watkins, 2002, Yusuf, 2001

13. Watkins, 2002

14. Stiglitz, 2003

15. Bhagwati and Srinivasan, 2002

16. Bhagwati et al, 2004

17. Dollar, 2003

18. World Bank Briefing Paper, 2001

19. Prahalad and Stuart

The above content was adapted from textbook content produced by Global Text Project and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0 license. Under this license, any user of the textbook contents herein must provide proper attribution as follows: The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the creative commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University. For questions regarding this license, please contact support@openstax.org. The original content can be downloaded for free at http://cnx.org/contents/6fdb38de-3019-4843-8ffd-2b204bc45c29@4