3rd edition as of August 2023

Module Overview

If you have taken abnormal psychology before, you know there are discrepancies in the diagnostic rate of mental health disorders for men and women. These differences have been attributed to biological differences, environmental differences, as well as methodological differences in data collection and symptom description. Therefore, the focus of this module is to identify gender discrepancies amongst mental disorders and discuss possible explanations for why these differences occur.

Module Outline

- 9.1. Methodological Artifact

- 9.2. Clinical Disorders

- 9.3. Suicide

- 9.4. Gender and Mental Health Treatment

Module Learning Outcomes

- Clarify how methodological artifact contributes to the gender bias in diagnosis of mental health disorders.

- State the gender discrepancies in rate of diagnosis for Major Depression Disorder, Anxiety Related Disorders, PTSD, and eating disorders.

- Outline various cognitive, social, and biological variables that contribute to the gender differences in selected mental health disorders.

- Describe the gender paradox of suicide.

- Identify variables that contribute to gender differences in seeking mental health treatment.

9.1. Methodological Artifact

Section Learning Objectives

- Explain how methodological artifacts contribute to gender bias in clinical psychology.

- Identify the types of clinician bias and how they impact diagnosis rate of mental health disorders.

- Clarify how response bias can impact diagnosis rate of mental health disorders.

Disparities in prevalence of clinical disorders between genders could be caused by factors other than gender itself. For instance, the findings of a study could be caused by a methodological artifact, which is when a research outcomes is due to the research technique or method used and do not reflect real-world data. Clinician bias and response bias are two ways in which methodological artifacts can occur. Additionally, the manifestation of symptoms is different among men and women, and instruments, such as questionnaires, can be biased to these symptoms.

9.1.1. Clinician Bias

Most people have accidentally misjudged someone at some time or another, only later to find out that their initial assessment was incorrect, and clinicians are no exception. The diagnosis of a psychological disorder requires the clinician to gather information from the patient, interpret the information along with their own observations, and determine whether or not the patient meets criteria for a diagnosis. This assessment is usually completed within the first couple of sessions when clinicians have very little information about their patient. Clinicians are required to use their informal and subjective method of arranging client data to formulate a diagnosis and treatment plan (Grove et al., 2000). Unfortunately, through this process, clinician judgement and subjective bias can occur, influencing the diagnosis.

While there are many different types of clinician biases, among the most common are pathology bias, confirmatory bias, and over-confidence in clinical judgement. Pathology bias suggests that clinicians may develop a bias to look for psychopathology, as their clinical training and experience has emphasized finding disorders (Shemberg & Doherty, 1999). This is especially problematic in settings where individuals are influenced to display psychopathology, such as in residential psychiatric settings.

Confirmatory bias can also lead to inaccurate diagnoses, as clinicians may have the tendency to recall only information that supports a diagnosis (Shemberg & Doherty, 1999). This is problematic in that clinicians will use this information to support their diagnosis, but not use data to refute their hypothesis, altering the true presentation of symptoms (Garb, 1998).

Finally, over-confidence bias occurs when clinicians become too confident in their subjective psychological assessments. While rarely observed in new clinicians, this bias often occurs in seasoned clinicians who believe more experience leads to greater effectiveness and accuracy in clinical judgment (Groth-Marnat, 2000).

9.1.2. Response Bias

Patient response bias is another type of bias which can lead to misdiagnosis. A patient is responsible for providing information about themselves, including presenting symptoms. Unfortunately, some patients tend to respond inaccurately or falsely to questions. While some of these errors may be unconscious, others may be intentional.

Studies have indicated that there are sex differences in attitudes toward various disorders, such as depression. Individuals tend to classify depression as a “feminine” diagnosis, and thus, may lead male patients to underreport symptoms (Page & Bennesch, 1993). This also extends beyond depression, as studies have shown both males and female clinicians are less willing to work with males than females with mental health disorders (Schnittker, 2000). Due to these cultural barriers, males may underreport their mental health symptoms to avoid being stigmatized.

9.2. Clinical Disorders

Section Learning Objectives

- State the prevalence rates of Major Depression Disorder in the United States.

- Outline variables that contribute to the gender differences in Major Depression Disorder.

- State the prevalence rates of anxiety disorders in the United States.

- Outline variables that contribute to the gender differences in anxiety disorders.

- State the prevalence rates of PTSD in the United States.

- Outline variables that contribute to the gender differences in PTSD.

- State the prevalence rates of eating disorders in the United States.

- Outline variables that that contribute to the gender differences in eating disorders.

In this section we will explore a few clinical disorders with gender variations in both diagnosis rate, as well as symptom presentation. Discussing gender differences among all disorders is beyond the scope of this book. However, if you are interested to learn more about the prevalence rate of mental health disorders we invite you to read Fundamentals of Psychological Disorders by Alexis Bridley and Lee Daffin.

9.2.1. Major Depression Disorder

According to epidemiological research, there is no significant gender difference in Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) during childhood; however, by young adulthood, girls are twice as likely to be depressed as boys and report approximately twice as many depressive symptoms as boys, a difference that holds in both community and clinical samples, even when accounting for gender differences in help-seeking behavior (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1987). While this discrepancy holds true until age 55, research exploring gender differences of MDD prevalence rates in older adults is inconclusive, with some reporting a continuation of this discrepancy and others failing to report any difference between genders among older adults.

Researchers have identified several reasons why studying prevalence rates of disorders among males and females is difficult. One recurring reason is the difference in symptom presentation among genders. Kahn and colleagues (2002) evaluated male/female twins on depressive symptoms. Findings indicated that females reported more fatigue symptoms such as excessive sleep, slowed speech and body movements whereas males reported more hyperactive symptoms including insomnia and agitation. The findings are consistent with other research that indicates women more often report “passive” symptoms such as sadness, lethargy, and crying, whereas men tend to associate depression with alcohol use. Due to the discrepancy in symptoms, it is not surprising that depression is more likely related to alcohol problems in males than females (Marcus et al., 2008). These findings are consistent when assessing for substance abuse disorders in general, with men more likely than women to not only have a substance abuse problem, but to also have a comorbid diagnosis of depression (Lai, Cleary, Sitharthan, & Hunt, 2005). This comorbidity not only complicates treatment for depression, but also willingness to seek mental health treatment in general.

9.2.1.1. Cognitive variables. Research regarding onset and treatment of depression routinely identifies the involvement of cognitive variables. Factors such as rumination and attributional style are among the most common factors assessed in gender research with regards to MDD. These factors not only explain differences in how males and females assess negative situations, but they also help clinicians to identify treatment interventions aimed specifically at factors contributing to an increase in depressive symptoms.

Rumination, or the response to negative moods by dwelling on them as opposed to problem-solving or distracting oneself, has been known to mediate the relationship between interpersonal stress and depression. More specifically, individuals with interpersonal stress and high levels of rumination report higher levels of depression than those with interpersonal stress and low levels of rumination (Lyubomirsky, Layous, & Nelson, 2015). When examining rumination with regards to gender, researchers routinely report that ruminating behaviors are more commonly observed in girls than boys (Johnson & Whisman, 2013; Rood et al., 2009; Grant et al., 2004). Given these findings, it should not come as a surprise that rumination also mediates depression within girls specifically, with girls experiencing higher levels of rumination also reporting higher levels of depression (Hamilton, Stange, Abramson, & Alloy, 2014). Interestingly, the relationship between males and rumination is the same, with males reporting higher levels of rumination also reporting significantly more symptoms of depression. Therefore, the pathway of increased ruminating thoughts leading to an increase of depressive symptoms appears to be the same in boys and girls, however, girls are more likely than boys to engage in ruminating thoughts in daily events.

Co-rumination, which is defined as a passive discussion of negative emotions and events with close friends is also observed more frequently in girls than boys (Barstead, Bouchard, & Shih, 2013; Bouchard & Shih, 2013; Rose, 2002). Unlike rumination where the relationship between increased ruminating thoughts and increased depressive symptoms did not differ between boys and girls, co-rumination appears to have a gender discrepancy. More specifically, engaging in co-rumination is correlated with increased depressive symptoms in girls, but not in boys (Rose, Carlson, & Waller, 2007).

In addition to ruminating on situations, one’s attributional style, or the way one interprets causes of events, has also been supported as a mediational variable to depression. More specifically individuals who attribute causes of events as internal, global, and stable are more likely to be depressed than those who view events as external, specific, and unstable (Morris, Ciesla & Garber, 2008). Researchers find that not only are girls more likely to attribute situations as internal, global, and stable, but they are also more likely to develop depressive symptoms from this attributional style than their male peers (Mezulis, Funasaki, Charbonneau, & Hyde, 2010). Thus, attributional style can predict depressive symptoms in girls, but not in boys.

Another cognitive vulnerability that is linked to depression with regards to gender discrepancy is interpersonal orientation, or the tendency to behave in certain ways around people. Girls, more than boys, affiliate needs and define themselves more in relational terms (Brody & Hall, 2010; Rose & Rudolph, 2006). Because of this need to establish specific relationships, girls report both more frequent and more intense stress related to interpersonal orientation. Interpersonal orientation has also been linked to adolescent girls increased risk for developing depression due in large part to peer relationships. In fact, adolescent girls with friends who are depressed are more likely to develop depression; this finding has not been proven in their male peers (Giletta et al., 2011; Prinstein et al., 2005).

Why does interpersonal orientation not effect boys? The short answer: it does; however, girls, more than boys, are more concerned about what peers think of them, and therefore, effects girls more often than boys. In fact, deficits in peer approval are strongly associated with emotional distress in girls but not boys (Rudolph, Caldwell & Conley, 2005). Furthermore, girls are more reactive to relationship problems than boys. The combination of placing more emphasis on relationships, as well as being more responsive to relationship problems, may explain why there is a gender difference in depression even among young children and adolescents (Rudolph, 2009).

9.2.1.2. Stress and coping. In addition to cognitive vulnerabilities, stress and coping of various life events also contributes to the development of MDD. Observed differences in both frequency of, and sensitivity to, various life events is one possible explanation for the gender difference in depression diagnoses. Findings suggest that adolescent girls experience more stressful life events than boys and rate these stressors with higher intensity than boys (Hammen, 2009; Seiffge-Krene, Aunola, & Nurmi, 2009; Hankin, Mermelstein, & Roesch, 2007). These findings are consistent in both the home and social settings. More specifically, girls who experience family discord report more symptoms of depression than boys and are at an increased risk for a depression diagnosis (Essex, Klein, Cho, & Kraemer, 2003; Crawford, Cohen, Midlarsky, & Brook, 2001). As stated above, girls also experience more stressful situations with peer relationships which has also been linked to increased depressive symptoms.

Stress can also be caused by social factors, such as gender roles, societal expectations, power imbalances, and gender discrimination. From an early age, girls are often socialized to prioritize the needs of others, develop strong interpersonal relationships, and suppress their own desires and emotions. This emphasis on self-sacrifice and emotional repression can increase the risk of depression later in life. Additionally, women face various forms of discrimination and unequal treatment, such as pay disparities, limited career opportunities, and gender-based violence, which can lead to chronic stress, feelings of powerlessness, and reduced self-esteem, which are risk factors for depression (Piccinelli & Wilkinson, 2000).

9.2.1.3. Biological variables. We already discussed the role of sex hormones in the development of various behaviors in Module 7, however, it is worth noting that those hormones are also important in the gender difference of depression diagnosis. The biological changes during puberty are related to an increase in sex hormones; however, levels of sex hormones alone do not account for the difference (Angold, Costello, Erkanli & Worthman, 1999; Brooks-Gunn & Warren, 1989). Research indicates that the onset of puberty in girls is closely linked with depressive symptoms, with early onset puberty in girls being more at risk for developing depression; these findings have been mixed for boys, with no clear distinction of how onset of puberty may or may not affect depression symptoms (Mendle, Harden, Brooks-Gunn, & Graber, 2010; DeRose, Wright & Brooks-Gunn, 2006; Graber, Seely, Brooks-Gunn, & Lewinsohn, 2004; Crick & Zahn-Waxler, 2003).

One possible explanation for the relationship between early onset puberty and increased risk of depression is the fact that physical changes that occur during puberty are negatively perceived by girls (Stice, Presnell, & Bearman, 2001). Furthermore, secondary sex characteristics that occur during puberty are seen as less desirable, particularly in Western cultures that value thinness (Richards, Boxer, Petersen, & Albrecht, 1990). These values can lead to negative body image, which has also been predictive of increased depression symptoms (Ohring, Graber, & Brooks-Gunn, 20002; Stice & Bearman, 2001).

Finally, differences in the HPA axis could be a contributing factor to the disparity in depression rates between men and women. As previously discussed in Module 7, women are more likely to have a dysregulated HPA axis, and therefore, are more susceptible to negatively interpreting stressful situations than men (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2001). Additionally, hormonal changes are also known to trigger HPA dysregulation, making women more vulnerable to depression, particularly after stressful situations. The role of the HPA axis in combination with coping style may predispose women to a susceptibility of depression.

9.2.2. Anxiety Disorders

Anxiety disorders are the most common class of mental disorders with an estimated 19% of US adults experiencing some anxiety disorder in the past year (NIMH). Similar to depression, women are nearly twice as likely to develop an anxiety disorder than men across the lifespan across all anxiety related disorders. In fact, by the age of 6, anxiety levels in girls are twice as high as in boys (Howell, Brawman-Mintzer, Monnier & Yonkers, 2001). The current prevalence rate for any anxiety disorder for adult females is 23.4%, and 14.3% for males. This discrepancy is similar in adolescents, with overall higher rates of anxiety reported in adolescent samples (38.0% females, 26.1% for males).

When examining specific anxiety related disorders, women are more commonly diagnosed with panic disorder, agoraphobia, specific phobias, generalized anxiety disorder, and both acute and post-traumatic stress disorder (McLean, Asnaani, Litz, & Hofmann, 2011; Gum, King-Kallimanis & Kohn, 2009; Bekker & van Mens-Verhulst, 2007). However, the sex differences are less pronounced, and sometimes not statistically significant, for social anxiety disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder (McLean & Anderson, 2009; Bekker & van Mens-Verhulst, 2007). Psychosocial, as well as genetic and neurobiological factors, likely contribute to the higher prevalence rate in women (Bandelow & Domschke, 2015).

The statistical difference between prevalence rates among genders is similar across all anxiety related disorders. Anxiety disorders represent a significant source of disability, especially for women. They are associated with more missed workdays for women, but not men. This may be related to a greater comorbidity of anxiety disorders among women, and thus more severe psychopathology in general. Interestingly, men but not women, were more likely to visit a professional for either an emotional or substance use issue in the past year if they had an anxiety disorder (McLean, Asnaanin, Litz & Hofmann, 2011).

9.2.2.1. Biological variables. There are a few theories that attempt to explain the difference in prevalence rates among anxiety disorders. Anatomically speaking, there may be structural and functional sex differences in brain regions relevant to anxiety. More specifically, there may be a difference in male and female brains involvement in learning, memory, fear conditioning, and fear extinction. For example, a study exploring blood pressure and pulse found women are more physiologically responsive than men when presented with potentially anxiety provoking situations (Altemus, 2006). Researchers argue that this finding may indicate that women are more easily conditioned to fearful stimuli than males (Farrell, Sengelaub & Wellman, 2013). Given the differences in fear conditioning, researchers have suggested that there may be a gender difference in fear extinction, impacting how the two genders respond to treatment of anxiety disorders.

Biologically, gonad hormones also play a role in the development and maintenance of anxiety symptoms. In women, estrogen and progesterone have been found to effect function of the anxiety related neurotransmitter systems, which in return, affect fear extinction (Lebron-Milad & Milad, 2012; Pigott, 1999). In fact, a study exploring the effects of long-term oral contraceptive use has been shown to alter the reactivity of the HPA axis in response to psychological stress (Biondi & Picardi, 1999). Testosterone also appears to play a role in the development of anxiety related symptoms. More specifically, testosterone has been linked to reduced responsiveness to stress and suppressing activity of the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis- the area responsible for our central stress response system. Although not as extensively researched as estrogen and progesterone, it does appear that gonad hormones likely account for some of the prevalence rate difference in anxiety related disorders.

9.2.2.2. Gender roles. One must also explore the impact of gender roles in the development of anxiety related symptoms. Cultural norms which emphasize women’s roles as caregivers and nurturers may lead to increased anxiety due to additional responsibilities and societal pressures (Parker & Brotchie, 2010). Furthermore, as mentioned before, women are more likely to experience gender-based discrimination, harassment, violence, trauma such as sexual and domestic abuse, all of which can lead to chronic stress and anxiety (Dworkin et al., 2017). Researchers examined anxiety differences between men and women while controlling for environmental stress and social desirability, reporting that gender socialization influences the prevalence of anxiety in women (Zalta & Chambless, 2012).

Some researchers argue that due to gender stereotypes of anxiety symptoms, men may underreport symptoms, thus leading to a reporting bias. This is supported by an increase in fear reports in males, but not females, when examined for a physiological fear response. More specifically, although men were not reporting significant levels of anxiety related symptoms, physiological responses to stressful situations indicated heightened arousal that researchers linked to anxious behaviors (Pierce & Kirkpatrick, 1992). Researchers suggest that due to social desirability, boys are more often encouraged to confront feared objects which leads to a greater exposure and extinction of fear responses, whereas girls are more supported in avoidance behaviors. This, coupled with increased rumination, may lead to more anxiety behaviors in girls across the lifespan (McLean & Anderson, 2009).

9.2.3. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) affects nearly 52 million Americans with a lifetime prevalence rate of 6.8%. Similar to both depression and anxiety disorders, women are more than twice as likely as men to develop PTSD at some point in their life. The lifetime prevalence rate for women is 9.7% and for men is 3.6% (NIMH, 2019). While research on PTSD in children and adolescents is not as extensive as it is in adults, what we know suggests a similar gender discrepancy with 8% of adolescent females meeting criteria for PTSD versus 2.3% of males.

Not only are women more likely to develop PTSD, but they also report a longer duration of posttraumatic stress symptoms (4 years for females vs. 1 year for males; Breslau, Davis, Andreski, Peterson & Schultz, 1997). This discrepancy may be due to the difference in types of traumatic events experienced. For example, men are more likely to experience traumatic events such as accidents, natural disasters, man-made disasters, and military combat, whereas women tend to experience events related to sexual assault, sexual abuse, and domestic violence (Breslau & Anthony, 2007). Sexual assaults were shown to be endemic and pervasive in a survey of 900 women, where one in four women had been raped, and one in three, sexually abused in childhood (Russell, 1984). Women are also more likely to report PTSD symptoms to other types of traumas. For example, when men and women were assessed after a recent earthquake, women reported higher levels of posttraumatic stress symptoms than men (Carmassi and Dell’Osso, 2016). This study was also replicated with motor vehicle accidents (Fullerton et al., 2001) and terrorism (Server et al., 2008). However, research shows that men underreport symptoms of PTSD, due to societal expectations of masculinity, with an emphasis on self-reliance, emotional restraint, and toughness (Vogel et al., 2011). The pressure to conform to such expectations can lead to the downplaying or suppression of PTSD symptoms, making it less likely for them to seek help or disclose their experiences. This could result in research outcomes due to methodological artifact.

9.2.3.1. Biological variables. The natural biological response to a stress or threat involves a complex interaction within the HPA axis, allowing for the individual to prepare for the stressor, and then return to baseline once the threat is over. As we discussed in Module 7, cortisol, the main hormone produced in a stress response, is produced by the adrenal glands in activation of the HPA axis. While research on cortisol levels during stressful or threatening situations is mixed, the general pathway suggests that production of cortisol is increased when the individual is under distress in efforts to help the individual “fight or flight” the stressful event. During periods of prolonged stress, the HPA axis undergoes significant dysregulation in efforts to produce the cortisol response (Chrousos, 2009).

Assessment of basal cortisol levels in healthy men and women suggest that women have lower cortisol levels than men, however, women demonstrate a slower cortisol negative feedback than men suggesting women experience prolonged physiological stress than men (Bangasser, 2013; Van Cauter et al., 1996). When examining corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF), the hormone responsible for initiating the HPA axis response that ultimately releases cortisol, women show greater expression of CRF than men. This finding has also been replicated in animal studies that show a sex differences in CRF receptor binding, signaling, and trafficking. Therefore, the fact that women are twice as likely than men to develop PTSD may be influenced by an underlying biological predisposition (Bangasser, 2013).

Salivary cortisol levels also appear to be different in men and women with diagnosed PTSD. More specifically, women with PTSD appear to have lower levels of salivary cortisol that decreased over time, whereas men with PTSD have higher levels that increased over time (Freidenberg et al., 2010). Gender difference in cortisol levels in response to trauma is also observed in children with PTSD, with female cortisol levels recorded higher than boys. Conversely, cortisol levels were higher in male but not female survivors of the World Trade Center attack (Dekel et al., 2013).

Research indicates production of estrogen may account for the gender differences in basal cortisol and glucocorticoid negative feedback, which may also explain why girls initially have higher rates of cortisol, but lower levels as adults. Through animal models, researchers have found that stress during adolescence, where there is a surge of gonadal hormones, impacts HPA axis reactivity and is associated with different behavioral responses in males and females (Viveros et al., 2012). Additionally, estrogen and menstrual cycle position have also been linked with intrusive memories (Cheung et al., 2013) fear inhibition and extinction (Glover et al., 2012, 2013) suggesting female hormone production may have a greater impact on women’s development of post-traumatic stress symptoms, as well as the biological mechanisms that facilitate stress response.

9.2.3.2. Cognitive variables. One of the diagnostic criteria symptoms of PTSD is intrusive recollection, or re-experiencing, of the traumatic event. Researchers have repeatedly found that these re-experiences, particularly the physiological reactivity related to the re-experiencing, were central to the development and maintenance of additional PTSD symptoms (Armour et al., 2017; McNally et al., 2017). Further studies found that increased re-experiencing of the traumatic event via dreams or distressing recollections initially following the trauma was predictive of PTSD six months after the traumatic event (Haag et al., 2017). Gender studies examining re-experiencing of symptoms identified women as having a higher level of both re-experiencing symptoms post-traumatic event, as well as a higher physical reactivity when remembering the incident (Fullerton et al., 2001; Stuber et al., 2006).

9.2.4. Eating Disorders

According to the DSM-V, there are three types of eating disorders- Anorexia Nervosa, Bulimia Nervosa, and Binge Eating Disorder. Anorexia nervosa involves the restriction of energy (i.e. food) that leads to a significantly low body weight for age, sex, and developmental status. These individuals have an intense fear of gaining weight or becoming fat, along with significant disturbance in their body evaluation. Bulimia nervosa involves recurrent episodes of binge eating followed by recurrent inappropriate compensatory behaviors in order to prevent weight gain. Finally, Binge Eating Disorder involves recurrent episodes of binge eating but not engaging in compensatory behaviors.

According to the National Eating Disorder Association, nearly 10 million American women and 1 million American men suffer from an eating disorder. Across all three disorders, women are more likely than men to be diagnosed with an eating disorder, however, the smallest gender discrepancy is found in binge eating disorder. Some argue the gender discrepancy is much less across all three eating disorders and that the current rate may be due to artifact, as men are less likely to report and seek help for disordered eating behavior (National Eating Disorder Association).

Eating disorders have the highest mortality rate of all mental health disorders, and of the three eating disorders, individuals diagnosed with anorexia nervosa having the highest mortality rate. Males may be at an increased risk of death because they are often diagnosed later due to the stigma associated with males and eating disorders. One interesting discrepancy between males and females’ development of eating disorders is weight history. Males who develop eating disorders are more likely to have been mildly to moderately obese at one point in their lives whereas women reported feeling fat but usually had a normal weight history (Andersen, 1999).

9.2.4.1 Societal variables. The most prominent theory behind the development of eating disorders may be the societal emphasis placed on physical attractiveness and thinness in women. This external variable is often compounded by the fact that women are interpersonally oriented, and thus value society’s opinion in their appearance. Unfortunately, society’s standards for thinness have grown to be more strict and unrealistic over past years, largely driven by media, magazines, and television. In fact, frequent magazine reading was associated with an increase in unhealthy weight control measures among female adolescents (van den Berg et al., 2007). These findings have also been replicated in men who read magazines about fitness and muscularity (Hatoum & Belle, 2004).

With the rise in social media over the past decade, individuals have increased access to, often manipulated, images of “ideal bodies.” There has been a rise in studies examining the effects of social media on mental health, particularly body image and eating habits. Researchers continue to identify a positive correlational relationship between time spent on social media and eating/body image problems. More specifically, individuals who spent more time on social media also reported increased negative eating behaviors. These findings may be even more significant in individuals who frequently viewed fitspiration images (National Eating Disorder Association). Americans who spend two more hours a day on social media are exposed to more unrealistic ideals of beauty, weight loss stories, body shamming, etc. While research with regards to social media use and eating disorders have failed to examine differences between genders, it is hypothesized that similar to magazine reading, men are also affected by the increased social media use as well.

9.2.4.2 Familial variables. Societal pressures can also come from family and friends. Girls are more likely than boys to receive criticism from parents or close family members to lose weight, whereas boys are often pressured by friends and family to gain muscle (Ata et al., 2007). Several studies have also identified that mothers of female eating disorder patients may have more impact on disordered eating habits than fathers. More specifically, direct negative maternal comments about weight and appearance may be a more powerful influence than modeling of weight and shape concerns (Ogden & Steward, 2000). With that said, modeling does appear to have a more significant impact on elementary age girls’ weight and shape-related attitudes. Thus, modeling of negative body image at an early age may contribute to the development of an eating disorder while overt comments may exacerbate symptoms in older girls.

Family dynamics have also been studied with regards to development of eating disorders. Although correlational at best, high levels of enmeshment, intrusive and overly hostile family environments are linked to eating disorders (Minuchin et al., 1978). Unfortunately, research in this area has not explored any differences in family dynamics and gender, therefore, we cannot determine whether enmeshment, intrusive, and overly hostile family environments impact the development of eating disorders in males.

9.2.4.3 Psychological factors. There are many individual factors such as low self-esteem, need for autonomy, and control that have been linked to the development of eating disorders. Unfortunately, most, if not all the research with regards to individual characteristics uses entirely female samples. Therefore, it is difficult to determine whether these factors also contribute to the development of eating disorders in men.

Individuals with eating disorders have a higher frequency of comorbid substance abuse than people who do not have eating disorders. Similarly, those who struggle with substance abuse also report increased disordered eating habits (Dunn, Larimer, & Neighbors, 2002). Interestingly, a gender discrepancy appears to exist with males reporting higher rates of comorbidity than females. More specifically, Costin and colleagues (2007) reported that roughly 57% of males with binge eating disorder struggle with substance abuse compared to only 28% of females with binge eating disorder. The high comorbidity between substance use and eating disorders has been linked to the use of stimulants to control weight. Due to the relationship between stimulants and weight management, treatment for the comorbid diagnoses is very difficult.

One area that is lacking in research, but should be addressed, is sexual orientation. Homosexuality appears to be a risk factor for eating disorders for men, but not women. Furthermore, eating disorders are more common among homosexual men than heterosexual men, but not among lesbians compared to heterosexual women (Peplau et al., 2009). Future research on eating disorders and sexual orientation may help clinicians identify more effective treatment methods, particularly for male patients.

9.3. Suicide

Section Learning Objectives

- Describe suicide rates in the United States.

- Describe the gender paradox in suicide.

- Outline factors that contribute to suicidal ideation and suicide attempts.

Suicide is ranked as the 10th leading cause of death for all ages in the United States. In 2016, it became the second leading cause of death for ages 10-34 and fourth leading cause for ages 35-54. While the government is dedicated to decreasing suicide rates by 2030, it has steadily increased over the past few years and across all age groups (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2019). In fact, the age-adjusted suicide rate increased 33% from 10.5 per 100,000 standard population to 14.0 from 1999-2017. Statistics specific to gender identify a higher suicide completion rate in males (18/100,000) than females (11/100,000); however, the rate of suicide over the past decade has increased more drastically for females (53%) than males (26%).

While data continually reflects a discrepancy between genders, some argue that it may be an artifact of biased data collection as women are more likely to report suicidal ideation/behavior than men. Conversely, death by suicide is more culturally acceptable for men than women, which also lends itself to another artifact of biased data collection.

9.3.1. Gender Paradox

When breaking down the statistics by gender, there are two trends that consistently hold true in Western cultures 1) females have a higher rate of nonfatal suicidal behavior and 2) males have a higher rate of suicide completion. Researchers have proposed several theories as to why this is the case. Intent of dying is one area that researchers have explored, where more attempts but no completions could indicate the intent of the attempt of suicide may not be completion. This finding has not been consistently supported among researchers, with most studies reporting that the intent on dying is equal in men and women who engage in suicidal behaviors. (Denning, Conwell, King, & Cox, 2010). So, if women are just as intent as men to die when engaging in suicidal behaviors, what else may explain this paradox?

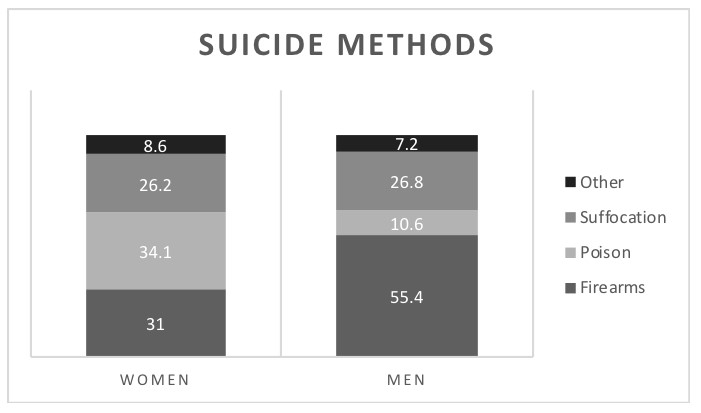

The method of choice when engaging in suicide behaviors has long been a discussion in the gender paradox. Men use more severe methods such as guns and hanging, whereas women are more likely to use drugs, over the counter and prescription, as well as carbon monoxide (see Table 10.1; Denning, Conwell, King, & Cox, 2010).

Table 9.1. Suicide Methods

The argument that choice of method reflects the intention to die has long been refuted in the literature as there is not a significant difference between men and women’s willingness to die with respect to suicidal behaviors (Nordentoft & Branner, 2008). With that said, because women are more likely to use more ambiguous methods, medications and poison, the actual rate of women’s suicides may be underreported as some deaths may be ruled “accidental,” another possible methodological artifact.

Cultural attitudes regarding masculinity and suicide have also been proposed as an explanation to the underreporting of men’s nonfatal behavior (Canetto & Sakinofsky, 1998). While suicide is not viewed as acceptable in most societies, it is viewed as more acceptable among men than women. Suicide completion itself is considered a more masculine behavior; however, suicide attempts are considered a more feminine behavior. Therefore, there may be an underrepresentation of the number of suicide attempts/nonfatal behaviors in men due to the social stigma attached to nonfatal suicide behaviors.

9.3.2. Factors Related to Suicide

There are many factors that have been linked to suicide in both men and women. Most commonly, substance abuse and depression are linked to suicide in adults. One problem with the depression explanation is the possible cyclical relationship between depression and suicide. More specifically, depression could lead to suicidal behavior, however, a failed suicide attempt could also lead to depression. When exploring the relationship between depression and suicide attempts, depressed men appear to be more at risk for serious suicidal behavior than women. Despite these findings, some researchers express caution in these statistics, as they may be representative of artifact of men avoiding seeking help for mental illness more than women. This is supported by studies that found men who kill themselves are less likely than women who kill themselves to have used mental health services (Payne et al., 2008).

The one exception to the strong link between mental health and suicide attempts with regards to mental health diagnoses is substance abuse. Men who engage in substance abuse are more likely to kill themselves than women. One possible explanation of this finding is that substance abuse, particularly alcohol use, is a more socially acceptable way for men to alleviate symptoms of mental illness (Sher, 2006). Therefore, while women are more likely to seek professional help for mental health problems, men are more likely to “self-medicate” through the use of alcohol.

Relationships are also important in discussing the gender discrepancy of suicide rates. The risk of suicide is higher in unmarried, divorced, and widowed persons than married persons, with the overall risk being higher for men than women (Payne et al., 2008). Being married and receiving social support may be a protective factor against suicide for women. It has been further discussed that from a gender role perspective, women are also expected to provide social support to families by taking care of the home, husband, and children, thus making them less likely to engage in serious suicidal behaviors.

In addition to relationships, financial status is also a strong predictor of suicidal behaviors. More specifically, individuals in lower socioeconomic status, those who are unemployed, as well as those that have financial problems are more at risk for suicide (Payne et al., 2008). These findings are more prominent in men than women. One possible explanation for the gender difference in suicidal rates with respect to financial status is related to gender roles. Men are historically viewed as the “bread winners” and the financial providers for the family. Therefore, when they are unable to fulfill this role, they may engage in more suicidal ideation and/or suicidal behaviors. This relationship may also be mediated by depressive symptoms, however, findings in support for this are inconsistent.

Finally, sexual orientation is also linked with suicidal behaviors, with sexual minorities reporting increased suicidal ideation and attempts than heterosexuals (Payne et al., 2008). While female sexual minorities are at an increased risk for suicidal behaviors, non-heterosexual males are at an increased risk as well.

9.4. Gender and Mental Health Treatment

Section Learning Objectives

- Outline factors that contribute to the gender discrepancy in seeking out mental health treatment.

- Compare and contrast how the male gender role and female gender role may impact men and women’s utilization of services.

- Describe feminist psychotherapy to include its goal, tenets, and criticisms of.

According to recent studies, only one-third of individuals who meet diagnostic criteria for a mental health disorder seek treatment, with women receiving treatment significantly more often than men (Andrews, Issakidis, & Carter, 2001). In fact, it is estimated that 1 in 3 women will receive mental health treatment at some point in their life compared to only 1 in 7 men (Collier, 1982). This is consistent with the trend that women seek out medical care more often than men. For example, men are more likely to utilize emergency services with respect to medical needs, whereas women are more likely to seek out appointments with a primary care physician (Husani, 2002; Rhodes & Goering, 1994). Models examining attitudes toward access of mental health treatment suggest that regardless of age and gender, negative attitudes toward treatment are largely responsible for the underutilization of mental health treatment.

Some argue that women have more psychological distress than men, hence the discrepancy in mental health treatment. This is not the case, as studies have shown that, despite women seeking counseling more often than men, men report similar, if not higher, rates of distress than women (Robertson, 2001). Although women are more likely to seek out treatment, men appear to benefit more from the intervention (Hauenstein et al., 2006).

In an attempt to better understand why individuals do and do not seek out mental health services, various models have been tested, including the suggestions in the previous paragraph. In recent years, researchers have explored the impact of gender roles and gender stereotypes, and how they may impact an individual’s willingness to seek out treatment. We will briefly discuss how male gender role and feminist theory have impacted mental health treatment among both men and women.

9.4.1 Male Gender Role

Male gender role socialization suggests that in order for men to receive mental health treatment they need to set aside their masculine socialization to seek out this help (Robertson, 2001). More specifically, because of cultural implications of what are considered socially acceptable masculine behaviors versus female behaviors, men are less likely to report emotional distress and seek out help than their female counterparts. This theory was supported in a study that found a significant relationship between adherence to the male gender role and men’s help-seeking attitudes and behaviors (Good, Dell, & Mintz, 1989). More specifically, as men’s views became less traditional, their desire to seek out psychological help became more positive. Additional studies assessing masculine attitudes and desire to seek help supported these findings with men who scored high on gender role conflict also reporting negative views of psychological help-seeking (Wisch, Mahalik, Hayes, & Nutt, 1995).

Gonzalez and colleagues (2005) examined how age, gender, and ethnicity/race impacted one’s attitude toward willingness to seek mental health treatment. Their findings indicated that younger individuals (under 24 years of age) were less willing to seek mental health treatment than their older counterparts. Similarly, men also had a more negative attitude toward mental health treatment and were nearly 50% less likely to seek mental health treatment as compared to females. Interestingly, when they explored an age by gender interaction, they found that younger males (under 24 years of age) were significantly less likely than females to seek mental health treatment. These findings also held consistent for older adults; however, when they examined willingness to seek mental health treatment between younger females (under age 24) and older male age groups (35-44 and 45-54), there was not a significant difference on willingness to seek mental health treatment.

These findings support gender role socialization, as men are conditioned to appear more self-reliant, and therefore, are less likely to seek assistance when needed. Men who report more traditional sex role orientation and independence have more negative attitudes toward seeking mental health treatment (Ortega & Alegria, 2002).

9.4.2. Feminist Psychotherapy

Feminist theory grew out of the women’s movement in the 1960’s. During this grassroots movement, women identified psychological structures of evaluation as contributing to women’s oppression and subordination in society, while also offering a scientific rationale for women’s secondary social status. In an effort to combat these issues, feminist psychotherapy was founded. The goal of feminist psychotherapy is to identify gender related challenges/stressors that women face as a result of bias, stereotypes, oppression, and discrimination. Through an equal relationship between the therapist and the patient, feminist psychotherapy helps patients to understand social factors that contribute to their issues, help them discover their own identity, and help build on personal strengths. Although labeled as feminist theory, any group that has been marginalized can benefit from feminist psychotherapy as the main goal of treatment is to identify individual strengths and utilize them to feel more powerful in society (Psychology Today).

According to Lenore Walker, there are six tenets of feminist psychotherapy:

- Egalitarian relationships: The equal relationship between patient and therapist models personal responsibility and assertiveness for other relationships.

- Power: Patients are taught to gain and use power in relationships.

- Enhancement of strengths: Patients are taught to identify their own strengths and use them effectively.

- Non-pathology oriented: Patient’s problems are seen as coping mechanisms and viewed in their social context.

- Education: Patients are taught to recognize their cognitions that are detrimental and encouraged to educate themselves for the benefit of all.

- Acceptance and validation of feelings: Patients are encouraged to self-disclose to remove the we-they barrier of traditional therapeutic relationships.

As stated above, the goal of feminist psychotherapy is to encourage change and establish empowerment in women and minority groups (Walker, 1978). One way therapists do this is by addressing gender issues as they can cause psychological distress and shape one’s behavior. Everyone is affected and influenced by stigmas and stereotypes. Feminist psychotherapy aims to help patients of minority groups to identify these stigmas and stereotypes, while simultaneously challenge them in an attempt to help improve the patient’s overall mental health.

Module Recap

In Module 9, we discussed the methodological artifacts from both clinician and reporting biases that may contribute to the gender differences among prevalence rates of mental health disorders. In keeping some of these artifacts in mind, we also discussed gender differences in rates of the most common psychological disorders – depression, anxiety, PTSD and eating disorders, as well as the biological, cognitive, psychological, and societal factors that contribute to these gender differences. It is important that you are able to identify these different factors as they contribute to differing rates of mental health disorders between men and women. We also discussed suicide and the gender paradox that although men complete more suicides, women are more likely to attempt suicide. We also identified the different methods men and women used when engaging in suicidal behaviors. The module concluded with a brief overview of how gender may impact one’s willingness to seek out mental health treatment and how feminist psychotherapy may help women and other minority groups address societal influences.

3rd edition