3rd edition as of August 2023

Module Overview

In this module, we will focus on a variety of domains regarding human sexuality. We will first examine the foundational studies of sexology. Then we will learn about sexual orientation and sexual fluidity. We will also learn about what it means to be transgender and the process of transitioning. Finally, we will examine gender and sexual roles including double standards in sexual behavior and “hookup culture.”

Module Outline

- 5.1. Sexology

- 5.2. Sex Education

- 5.3. Sexual Orientation

- 5.4. Transgender

- 5.5. Gender Roles and Rules for Sexual Behavior

Module Learning Outcomes

- Describe the origins of the study of sexual behavior.

- Identify sex education programs in the U.S.

- Define sexual orientation and describe the complexities of identity, attraction, expression, and anatomical sex.

- Clarify how gender roles impact sexual behaviors.

5.1. Sexology

Section Learning Objectives

- Describe the beginnings of sexology by Dr. Alfred Kinsey.

- Clarify Masters and Johnsons contribution to our knowledge about the human sexual response cycle.

- Describe findings of the largest U.S. study of sexual behaviors.

5.1.1. Alfred C. Kinsey

Dr. Alfred C. Kinsey, a biologist, sexologist, and zoologist, founded the Institute for Sex Research in 1947 located at Indiana University. In 1981, the institute was renamed The Kinsey Institute for Sex Research (“Dr. Alfred C. Kinsey,” n.d.).

Kinsey is often credited for shifting the perception and understanding of human sexuality through empirical research. This was monumental, because former study of human sexual behavior had been limited to moralistic judgements and anecdotal evidence. His research focused on frequencies and occurrences of sexual behavior and included thousands of face-to-face interviews to obtain sexual histories, believing this method would increase the likelihood of obtaining honest answers (“Dr. Alfred C. Kinsey,” n.d.). However, he recognized that he and his team would have to be carefully trained so as not to react in a judgmental way in order to gain as much trust from their interviewees as possible. He assured interviewees of confidentiality, and to this date, there is no known breach of identities of those interviewed. Eventually, Kinsey and his team gathered the sexual histories of 18,000 individuals.

Here is one such example: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TIGzC_Fmh5c.

The collected sexual histories were published by Kinsey in two separate works: Sexual Behavior in the Human Male, published in 1948, and Sexual Behavior in the Human Female, published in 1953. The reports that Kinsey’s team gathered are often referred to as the Kinsey Reports (“Dr. Alfred C. Kinsey,” n.d.).

Dr. Kinsey also developed the Kinsey Scale (originally known as the Heterosexual-Homosexual Rating Scale). A link cannot be provided as it is not an actual physical test. Rather, the scale is used by an interviewer from Kinsey’s team to rank an individual based on their self-reported sexual history from 0 to 6. The numbers reflect a continuum on which the extreme low score indicates solely heterosexual behaviors and attraction, the highest score reflects solely same-sex behavior and attraction, and the middle area of the spectrum reflects varying attraction and behavior for both sexes. (“The Kinsey Scale,” n.d.).

5.1.2. Masters and Johnson

Shortly after Kinsey laid the foundation for sexual research, William Masters and Virginia Johnson began researching human sexual responses in the late 1950’s. Although Kinsey had focused on the frequency of various sexual behaviors, Masters and Johnson sought to study anatomy and physiological responses in the human body during sexual experiences. They began their work in St. Louis at Washington University and later founded the Reproductive Biology Research Foundation which later was known as the Masters and Johnson Institute (“Masters & Johnson Collection,” n.d.). Their work required the direct observation of sexual activity (i.e., manual masturbation or sexual intercourse). Masters and Johnson were criticized for participant samples that weren’t representative of the population, being predominantly middle-class, white, and heterosexual. Sex workers were also used in their research, which drew scrutiny over issues of ethics.

Masters and Johnson are most known for their sexual response cycle theory. Prior to this, not much was known about the cycle and process of sexual responses. Their theory proposed that sexual response occurs in four stages: Excitement (1), Plateau (2), Orgasm (3), and Resolution (4) (Crooks & Baur, 2013).

- Excitement Phase – This is when myotonia (i.e. muscle tension increases throughout the body and both involuntary contractions as well as voluntary muscle contractions), vasocongestion (when tissue fills with blood due to arteries dilating which allows blood to flow to tissue at a rate faster than veins can move the blood out of the tissue, leading to swelling), high heart and breathing rates, and increased blood pressure occur.

- Plateau Phase – During this phase, there is a surge of tension that begins and then continues to increase in the body. Blood pressure and heart rate surge. This usually lasts anywhere between a few seconds to a few minutes. The longer this phase is, typically, the more intense an orgasm is.

- Orgasm Phase – This is typically the shortest phase and is the climax period in which blood pressure and heart rate peak and involuntary pelvic muscle spasms occur, accompanied by intense physical pleasure.

- Resolution Phase – When myotonia and vasocongestion dissipate and the body returns to a state of pre-arousal.

This same cycle, and order, is experienced no matter the sexual stimulation/activity (e.g., masturbation, vaginal intercourse). How intense the cycle/phases are, and how rapidly one moves through them, varies depending on the sexual activity. Moreover, men and women experience each stage in the same order, but there are some differences within the cycle between men and women. For example, women may more easily experience multiple orgasms than men, though it is possible for men to have them. Additionally, while men and women both experience a refractory period after climax, the length of refractory time may be different (Humphries & Cioe, 2009). Another important difference is that although men and women experience these phases in the same order, males move through the entire cycle significantly more often than women during heterosexual encounters (Mahar et al., 2020). One study showed that 80 percent of women pretended to reach the orgasm phase of the cycle about half the time during vaginal intercourse (Brewer & Hendrie, 2011).

5.1.3. National Survey of Sexual Health and Behavior

Indiana University is also known for the largest sex-focused survey to be conducted in the United States – the National Survey of Sexual Health and Behavior. The survey’s first wave of participants and data was collected in 2009. The study, in total, has over 20,000 participants ranging in age from as young as 14 and as old as 102. The survey data has led to over 30 different research publications/articles. In general, the survey has included items that address and explore a variety of sex-related domains including, but not limited to condom use, intimate behaviors (e.g., kissing, cuddling) as they relate to sexual arousal and intimacy, sexual behavior patterns in varying sexual orientations, sexual identities, sexually transmitted disease knowledge, and relationships/relationship patterns (“NSSHB,” n.d.).

Results from the first wave of data collection revealed that a majority of U.S. youth are not engaging in regular intercourse; condom use was not perceived by adults to reduce sexual pleasure; men are more likely than women to have an orgasm during vaginal intercourse; although less than 7-8% of participants identified as gay, lesbian, or bisexual, a much higher percentage reported engaging in same-sex behavior at some point; women are more likely to identify as bisexual rather than lesbian; males perceive that their partners orgasm more often than women report actually orgasming (and male/male sexual occurrences do not account for the discrepancy); older adults continue to report active sex lives, and the lowest rate of condom use is in adults over 40. From more recent waves of data, the following has been found: women tend to be more open and accepting of individuals that identify as bisexual than males are, most people report being in a monogamous relationship, same-gender sexually oriented individuals are less likely than opposite-gender sexually oriented individuals to report monogamy, (“NSSHB,” n.d.).

5.2. Sex Education

Section Learning Objectives

- Describe sex education programs.

- Describe comprehensive sex education programs and clarify how effective they are.

5.2.1. Overview

Sex education varies greatly throughout the United States, being either a) abstinence-only (AO) in which abstaining from sexual activity is taught to be the only option to avoid negative outcomes related to sex; b) abstinence-plus (Aplus) in which abstinence is encouraged but some information about contraception and condoms is given; c) or comprehensive (CSE) in which medically-accurate information about sex, reproduction, protection and contraception, gender identity, and sexual orientation is covered. Although about half of U.S. states require that some form of sex education be provided, only 13 require the material presented to be medically accurate. Moreover, most states require that if sex education is presented, abstinence must be included, whereas only a minority require that contraception education be included (Abstinence Education Programs, 2018).

Abstinence-only was heavily federally funded in the 1980’s making it highly incentivized. AO programs peaked during the Bush administration and then began dropping during the Obama administration. In 2017, about 1/3 of funds were provided for AO programming. Proponents of abstinence-based education argue that this type of education delays teens first sexual encounter and reduces teen pregnancy. However, research does not support those claims. In fact, studies reveal that when teens who received abstinence-based education had sex, that it was more likely to be unprotected. Additionally, although youth educated through this program have more knowledge about STIs, they actually have less knowledge about condoms and how effective condoms are at preventing STIs (Abstinence Education Programs, 2018). Moreover, some statistics show that an emphasis on AO programs may be correlated with higher teen pregnancy rates (Stangler-Hall & Hall, 2011), which is consistent with the above statistic revealing that youth that receive AO programming are more likely to have unprotected sex.

5.2.2. Comprehensive Sexual Education (CSE)

Comprehensive sexual education programs cover sexual education in depth and are not simply limited to concerns of risk reduction. These programs focus on human development, physical anatomy of humans and sexual responses, attraction, gender identity and sexual orientation, and contraception and protection. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommended that CSE programs contain medically accurate information that is appropriate for the age of the audience. A CSE program may focus on providing not only information about pregnancy and STIs, but also other benefits to delaying intercourse, as well as information about reproduction and contraception (The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2016).

CSE has been shown to reduce sexual activity, risky behaviors, STIs, and teen pregnancy in youth. Kohler, Manhart, and Lafferty (2008) compared abstinence-only to CSE programing and found that youth that received CSE programming had fewer occurrences of teen pregnancy compared to youth that received no programming, but no significant difference in rates occurred between AO and CSE. However, AO had no impact on delaying initial intercourse, whereas CSE had minor impacts on lowering the likelihood of intercourse (Kohler, Manhart, and Lafferty, 2008).

A meta-analysis comparing AO and CSE showed that AO does not delay initial intercourse and less than half of programs had a positive impact on sexual behavior. However, 60% of CSE programs showed positive impacts including delayed initial intercourse and increased use of condoms/contraception (Kirby, 2008). Individuals receiving CSE were also 50% less likely to become pregnant as a minor compared to youth that received AO programming. Youth receiving CSE programming were found to be less likely to have sex in general, more likely to delay their first sexual encounter, have fewer sexual partners, and when they have sex are more likely to engage in protected sex compared to youth that receive AO programming (Abstinence Education Programs, 2018).

5.3. Sexual Orientation

Section Learning Objectives

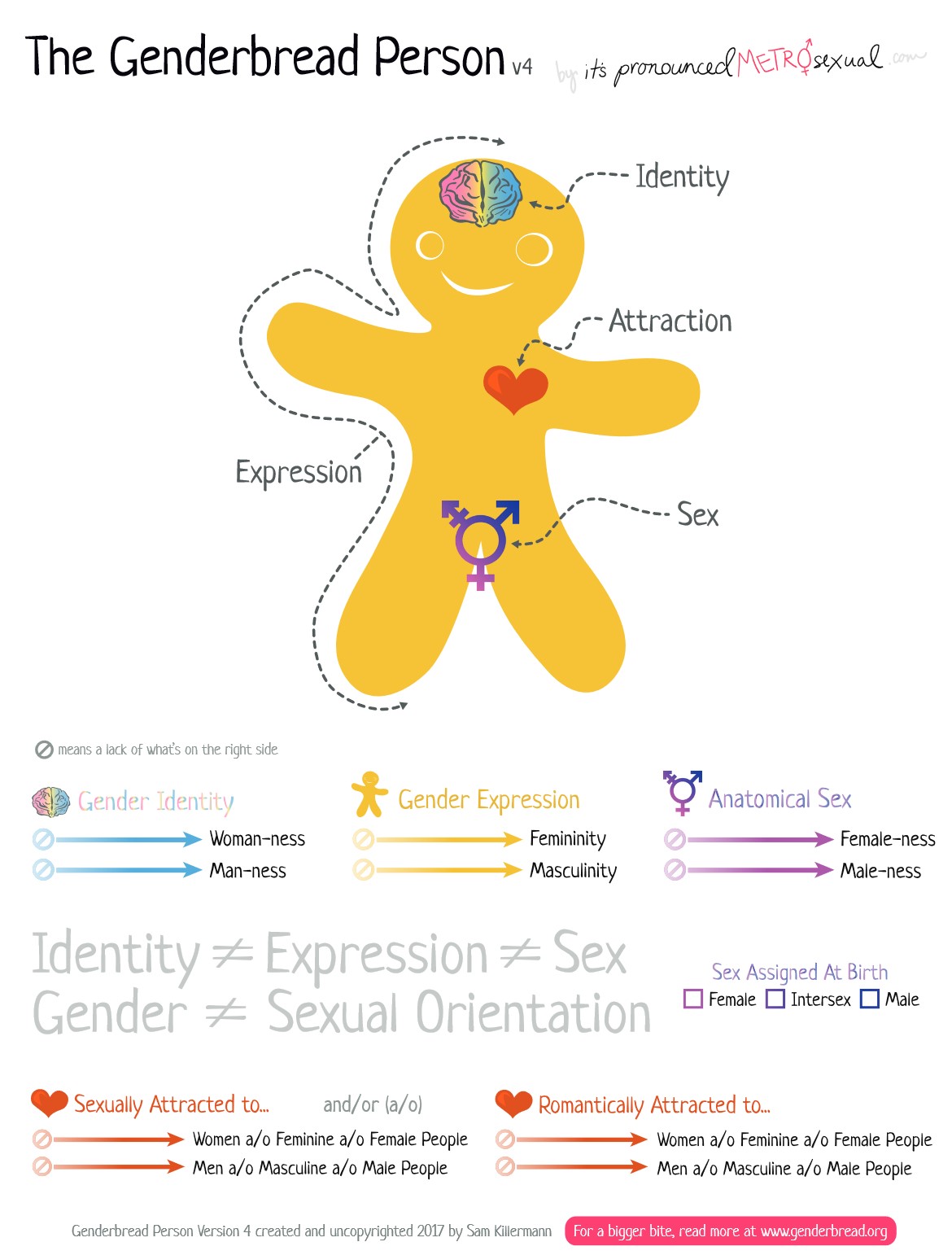

- Clarify what the Genderbread Person is and how it helps conceptualize sexual orientation and identity.

- Identify and define the various sexual orientations.

Sexual orientation is the part of one’s identity that involves attraction to another person, whether in a sexual, emotional, physical, or romantic way. Orientation has been defined as binary: either heterosexual (opposite-sex/gender attraction) or homosexual (same-sex/gender attraction). However, sexuality research and awareness efforts have led to discussions considering orientation on a continuum that includes a variety of orientations, which we will discuss.

5.3.1. Genderbread Person

Before we go into detail with some of the broader orientations, let’s first discuss the Genderbread person (Killerman, 2017). This is important because it helps us understand orientation, on a continuum, as it relates to various aspects such as birth sex, anatomical sex, gender identity, gender expression, sexual attraction, and romantic attraction.

5.3.1.1. Sex. We are all born with a biological sex. However, one’s current anatomical sex may or may not align with one’s birth sex, particularly if a transsexual individual has undergone sexual reassignment surgery (we will discuss this more later on).

5.3.1.2. Gender identity. This deals more cognitions and thoughts about ourselves and is how we identify. One can be biologically female but identify as a man. Like orientation, there is a continuum of identification. Identity is not determined by either anatomical sex, gender expression, or sexual or romantic attractions. One may be biologically female, identify as a man, wear stereotypically feminine clothes, be attracted sexually to men, and be attracted romantically to women – or any combination or variation.

5.3.1.3. Gender expression. Gender expression is how one acts, dresses, and portrays themselves in regard to gender norms. One may present themselves as extremely masculine or feminine. One may present as androgynous, meaning gender-neutral or equally masculine and feminine. Gender expression can also change, not only from day to day, but moment to moment. For example, a woman getting ready for a date with her wife may dress up and express very feminine gender norms; however, that same woman may have expressed very masculine norms and behaviors an hour earlier when playing in her recreational dodgeball league.

5.3.1.4. Attraction. When discussing attraction, we need to be aware that it takes two forms – sexual and romantic. Remember, just like everything else we have discussed, one does not determine the other. For example, one may be romantically attracted to men, but sexually attracted to women. One may have romantic attraction to either or both men and women, but not be sexually attracted to either, etc. Sexual attraction refers to who you are aroused by and desire to be sexually intimate with. Romantic attraction refers to who you seek and desire in an emotional way.

Figure 5.1. Genderbread Person (direct source: Sam Killerman – https://www.genderbread.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Genderbread-Person-v4.pdf)

5.3.2. Asexuality

Asexuality is a sexual orientation characterized by the lack of sexual attraction to another individual – it is not a sexual disorder. Asexuality is one of the most understudied orientations, and there is some debate as to whether asexuality is the lack of orientation or an orientation itself. Only about .5- 1% of the population identifies asexual, but it is thought that this is potentially a slight underestimate. Individuals that identify as asexual are predominately white (Deutsch, 2017).

Being asexual does not mean an individual refrains from sexual behavior or intercourse. It is also not defined by virginity, having a low sex drive, or masturbation. Individuals that are asexual may experience physical, sexual arousal. Although some may be disturbed or disgusted by their own arousal, others may simply not feel connected to individuals or their arousal which is known as autocrissexualism (Deutsch, 2017).

Asexuality exists in various forms – we will cover some, but not all. For example, gray asexuality is an orientation in which an individual experiences low levels of attraction, whereas demisexuality is an orientation in which an individual only experiences sexual attraction when a close bond is formed. Keep in mind, an individual that identifies as asexual may still have romantic attractions toward any gender (Deutsch, 2017).

5.3.3. Heterosexual

Heterosexual is defined as being solely attracted to the opposite gender. A majority of the population identifies as heterosexual, and much of our cultural assumptions and biases are due to this. Historically, heterosexuality has been considered ‘normative,’ and thus, anything other than heterosexualism was ‘abnormal.’ Fortunately, there has been significant efforts to shift this mindset, but the lasting impacts of this are still present today.

5.3.4. Same-Gender Sexuality

Although rates vary depending on which study and statistic is cited, approximately 3.5% of the U.S. population identifies as being sexually attracted to the same-gender (same-gender sexuality, homosexuality; Gates, 2011). Specifically, about 2-4% of males and 1-2% of females identify as being homosexual. However, women are 3 times more likely to report having engaged in some same-gender sexual behavior at some point in life compared to men. Moreover, although less than 5% identify as homosexual, about 11% of individuals report being attracted, to some degree, to same-gender individuals and 8.2% reported same-gender sexual behavior (Gates, 2011).

Same-gender attraction can be exclusive, meaning that the individual is only attracted to same-gendered individuals, and individuals may use labels such as gay (males) or lesbian (females) to define/describe their orientation. However, some individuals may be attracted to both same- and opposite-gendered individuals, which is often described as bisexual. Women are more likely to identify as bisexual than men (Copen, Chandra, & Febo-Vazquez, 2016). Women are also are more accepting of bisexual individuals then men. In general, bisexual women are more accepted than bisexual men in society (Dodge et al., 2016).

5.3.5. Sexual Fluidity

Sexual fluidity is a concept in which we move away from thinking in binary ways (heterosexual or homosexual) and move into a more fluid understanding – essentially the entire premise behind the Genderbread Person. An individual that is bisexual, may be considered to have sexual fluidity; however, pansexual individuals likely align with sexual fluidity a bit more. Pansexual is a word used to identify individuals that are attracted to all genders either in sexual, romantic, or spiritual ways (Rice, 2015). How are pansexual and bisexual different? Well, bisexual (in the name) indicates a binary requirement (male or female) whereas pansexual indicates an individual is attracted to a spectrum of genders (and does not consider gender to be binary; Rice, 2105).

5.4. Transgender

Section Learning Objectives

- Define the term transgender.

- Describe gender dysphoria.

- Describe the process of transitioning.

5.4.1. Defining Transgender

Transgender and transsexual do not refer to a sexual orientation. These terms define an individual’s gender identity and/or anatomical sex. Transgender is a term used to define an individual that identifies with a gender that does not align with their biological sex. For example, an individual that is born a female, but identifies as male, may label themselves as transgender. Transsexual is an older term that is used less often today. This term was used to specifically identify individuals that identify with a gender inconsistent with their biological birth sex and sought medical interventions (such as hormone therapies, surgical reassignment) to change their hormonal and/or anatomical makeup to align with their self-identified gender more closely. Although some transgender individuals may wish to seek medical interventions, one should not assume that someone that is transgender has a desire to pursue such interventions. Also, sexual orientation varies in transgender individuals, just as it does in cisgender (when a person’s gender identity and birth sex align) individuals.

Male-to-female (MtF) and female-to-male (FtM) are terminology often used to help individuals communicate and understand their identity. Specifically, MtF indicates an individual who was born with male genitalia and chromosomal/hormonal makeup and that has transitioned to female genitalia and/or hormonal therapy or they may perhaps even change legal documents or how they dress to align with their gender identity more closely if they do not desire medical interventions. When referring to a transgender person’s gender, one should use the pronouns the individual uses for themselves, which often is related to their stage of transitioning. For example, if a FtM individual is transitioned and refers to himself as male, one should also use male pronouns and not female pronouns.

Approximately 0.3% of adults identify as transgender. About 27% of MtF individuals are attracted to men, 35% to women, and 38% to both men and women. About 10% of FtM individuals are attracted to men, 55% to women, and 5% to both men and women (Copen, Chandra, & Febo-Vazquez, 2016; Gates, 2011).

5.4.2. Gender Dysphoria

Transgender is not a disorder. However, the DSM-5 includes a diagnosis of gender dysphoria, which is generally defined as when a person has significant internal distress due to feeling that their biological sex is incongruent with their gender identity. Many transgender individuals experience gender dysphoria. In fact, gender dysphoria in children persists to adulthood in anywhere between 12 to 27 percent of individuals (Coleman, et al., 2012). However, heterosexual and homosexual individuals may experience gender dysphoria alike, as gender identity is independent from sexual orientation.

5.4.3. Transitioning

Transitioning is the process of moving from living one’s life as the gender that aligns to their birth sex, to the gender to which the individual identifies. Transitioning can involve a variety of steps, including changing one’s name on legal documents, dressing in a way that aligns with one’s gender identity, utilizing noninvasive procedures (hair removal, makeup tattooing), hormone therapies, and sex reassignment surgeries.

5.4.3.1. MtF. Surgery may consist of facial feminization in which plastic surgeries are conducted to feminize one’s face, breast augmentations, either the enhancement or reduction of the buttock, vaginoplasty (conversion of male scrotum and penis to a vagina with a clitoris and labia), and thyroid cartilage removal (to reduce the appearance of an Adams Apple). Nonsurgical options might include hormone therapy, voice training, hair removal, and other minor procedures such as Botox (The Philadelphia Center for Transgender Surgery, n.d.).

5.4.3.2. FtM. Surgery may consist of chest masculinization (removal of the female breasts), phalloplasty/metoidioplasty (either constructing a penis and scrotum or releasing the clitoris to create a micropenis), buttock reduction, etc. Nonsurgical options include hormone therapy and voice training (The Philadelphia Center for Transgender Surgery, n.d.).

5.4.3.3. Prerequisites for surgery. Before surgery options can occur, various prerequisites must be met by an individual, typically including (1) the individual is experiencing true gender dysphoria., (2) at least one, but often two, mental health providers that specialize in gender identity concerns recommending the individual for surgery (must specialize in gender identity), (3) has received hormone treatment for at least one year, (4) has been living as the gender they identify as for at least one year, (5) is considered emotionally stable, and (6) is medically healthy. (The Philadelphia Center for Transgender Surgery, n.d.).

Hormone therapy involves taking a prescription of hormones to produce secondary sex characteristics in the gender one identifies with. Hormone therapies appear relatively safe for transgender men (FtM), but for women (MtF), there is a 12% risk of a negative medical event such as a thromboembolic or cardiovascular occurrence (Wierckx, 2012).

5.5. Gender Roles and Rules for Sexual Behavior

Section Learning Objectives

- Define sexual script theory.

- Describe scripts for sexual behavior.

- Defend the existence of a double standard.

- Describe the hookup culture.

5.5.1. Scripts for Sexual Behavior

Sexual script theory proposes that we engage in particular sexual behaviors due to learned interactions and patterns. We learn this “script” from our environment, culture, etc. We adjust our behaviors to fit the script so as to align with general expectations. Scripts are often influenced, largely, by culture and are frequently heteronormative. We learn scripts from people in our life, and those same people, as well as society and media, reinforce those scripts. Scripts are also influenced by our interpersonal experiences (experiences with others) and intrapersonal experiences (internalization of scripts). What our culture teaches us about scripts plays out in interpersonal experiences. How we interact with our partner may be largely based on engaging in behaviors that align with culturally congruent scripts. This often leads to patterned script behavior within partners. For example, if a man in a heterosexual relationship is the one who always initiates sex in the beginning (based on sexual script), then over time, his partner may continually wait for him to initiate sex in the future. This is now an interpersonally-based script that started from a broader, culturally-based script. This may become internalized and repeated in other relationships for the woman (intrapersonal influence on scripts). There may also be very negative feelings if one contradicts a generally accepted sexual script (e.g., guilt for not acting like other women, etc.; intrapersonal experience).

The heterosexual script is the most prominent in the US, and it consists largely of three specific components including a double standard, courtship roles, and desire for commitment (Helgeson, 2012). As for the double standard, women are often scripted to be timid, hesitant, and passive in sexual encounters and interactions, whereas men are scripted to be aggressive, dominant, and in control. Women are expected not to engage in sex outside of a relationship, whereas men are expected, and often praised, for doing so. Men are supposed to desire sex whereas women should resist it (Seabrook, et al., 2016). In terms of courtship roles, men are scripted to initiate sex and to be more sexually advanced and experienced than women, desire sex in uncommitted contexts, and have more sexual partners than women. Women are scripted to be desired, have lower sex drives than men, to wait for a male to initiate sex and then resist it, and be less sexually experienced than men. In relation to commitment, whereas women are scripted to desire intimacy, trust, and committed relationships, men are not (Masters, Casey, Wells, & Morrison, 2013).

Research by Garcia (2010) suggests that there could be a risk to rejecting adherence to scripts. If a man holds a belief in a traditional sexual script, such as men being the breadwinners, he might criticize his partner for her career accomplishments. She may also be judged negatively and experience direct or indirect ‘punishment’ or negative consequences as a result of the non-conforming behavior (Garcia, 2010). This in no way substantiates or validates the script, but points to the fact that communication in a relationship is key, and early on. Both individuals should set clear expectations of their partner from the beginning to avoid awkward situations such as this.

5.5.2. Researching the Double Standard

The double standard in sexual behavior began to be researched in the 1960’s by Ira Reiss. Reiss studied the double standard in the context that society prohibited women to engage in premarital sexual behavior but allowed men to do so (as cited by Mihausen & Herold, 1999). The double standard impacts a variety of sexual factors such as age of first intercourse (men being younger), number of sexual partners (men having a more), etc. Regarding sexual behavior, males, even in adolescence, are often praised for sexual conduct and promiscuity whereas females are often shamed. Males are more accepted by their peers as sexual partner counts increase whereas females are less accepted by their peers (Kraeger & Staff, 2009). Kraeger (2016) also found that a girl having a sexual history, led to a gradual decline in peer acceptance, whereas males with the same history experienced an increase in peer acceptance. Interestingly, although much of the above information is related to the double standard related to sex, may that be intercourse, oral sex, etc., there appears to be a slightly different story with kissing or “making out.” Girls are more accepted by their peers, whereas boys are less accepted, when it comes to making out (Kraeger, 2016). Reflections of the double standard may not be just in perceptions and attitudes, but in actual sexual encounters. In hookups, males reach orgasm more often than females (Garcia et al., 2010).

Milhausen and Herold (1999) found that although women believe there is still a sexual double standard, they denied that they held the double standard themselves. Moreover, participants believed other women, more than men, held the double standard though the research shows that men tend to hold double standards. Overall, on average, the double standard is still present. Although young men and women are challenging it, in general, the double standard persists. For example, ¾ of individuals reject the double standard when considering hooking up, but at least ½ of individuals hold some amount of a double standard (Sprecher, Treger, & Sakaluk, 2013; Allison and Risman, 2013).

5.5.3. Hookup Culture

A ‘hookup’ is defined as an event in which two individuals that are not committed to each other, or dating, engage in sexual behavior, which can include intercourse but may also include oral sex, digital penetration, kissing, etc. Typically speaking, there is no expectation of forming a romantic relationship or connection with each other (Garcia, Reiber, Massey, & Merriwether, 2013). ‘Hooking up’ is becoming more socially acceptable and a common experience for young adults in the U.S. In the 1920’s, sexual promiscuity and casual sex became more open and accepted. As time progressed, and medicine advanced (e.g., birth control), the acceptance of openly discussing sex and the frequency of casual sex, or sexual behavior that broke previous, traditional and/or moral/religious boundaries (e.g., only having sex in marriage) became more common. Today, the term friends with benefits (FWB) describes a relationship in which two people contract to have purely sexual intimacy but do not date, emotionally-bond, etc. Sixty percent of college students report having a FWB relationship at some point.

There are some gender differences in frequency and feelings after hooking up. Women are more conservative than men regarding causal sex attitudes. In general, both males and females report varied feelings. About half of men report feeling positive after hooking up, about 25% report feeling negative, and the remaining 25% report mixed feelings. For women, things are reversed – about 25% feel positive, 50% feel negative, and 25% report mixed feelings. Although the data is mixed, statistics often show that around ¾ of people, in general, report feeling regret after a hookup. Two factors that seem to lead to regret is a hookup with someone that the individual just met less than 24 hours before and someone they hookup with only once. Men may be more regretful because they feel they used someone whereas women may feel regret because they felt used. In general, women have the most negatively affective impacts from hookups (Garcia et al., 2013).

A majority of college students did not fear contracting an STI following a hookup and less than half used condoms during a hookup. Factors leading to hookups vary. Substance use is highly comorbid with hooking up, especially alcohol. This often leads to unintended hookups. Feeling depressed, isolated, or lonely is a common factor leading to hookups. In general, individuals who have lower self-esteem are more likely to participate in hooking up. (Garcia et al., 2013). The impact of hookups varies as well. If an individual experienced high levels of depression and loneliness, they sometimes report experiencing a reduction in this following a hookup. However, if an individual did not have depressive symptoms prior to a hookup, they may be more at risk for developing depressive symptoms afterward (Garcia et al., 2013).

Module Recap

In this module, we first focused on understanding the beginning stages of researching human sexuality. We then examined and learned about various sexual orientations. Additionally, we discussed transgender and the process one goes through to transition. Finally, we examined gender and sexual roles including double standards in sexual behavior and the “hookup culture.”

3rd edition