Module 7 – Intellectual Disability Intellectual Developmental Disorder (IDIDD) & Learning Disorders

3rd edition as of August 2022

Module Overview

In Module 7, we will discuss matters related to intellectual developmental and learning disorders to include their clinical presentation, prevalence, comorbidity, etiology, assessment, and treatment options. Our discussion will include intellectual developmental disorder (intellectual disability) and specific learning disorder. Be sure you refer Modules 1-3 for explanations of key terms (Module 1), an overview of the various models to explain psychopathology (Module 2), and descriptions of the various therapies (Module 3).

Module Outline

- 7.1. Clinical Presentation

- 7.2. Prevalence and Comorbidity

- 7.3. Etiology

- 7.4. Assessment

- 7.5. Treatment

Module Learning Outcomes

- Describe how intellectual developmental disorder and specific learning disorder present.

- Describe the prevalence of intellectual developmental disorder and specific learning disorder.

- Describe the etiology of intellectual developmental disorder and specific learning disorder.

- Describe how intellectual developmental disorder and specific learning disorder are assessed, diagnosed, and treated.

7.1. Clinical Presentation

Section Learning Objectives

- Describe the presentation and associated features of intellectual developmental disorder.

- Describe the presentation and associated features of specific learning disorder.

- Clarify the differences and similarities between intellectual developmental disorder and specific learning disorder.

7.1.1. Intellectual Developmental Disorder (Intellectual Disability)

At the core of an intellectual disability is a deficit in cognitive or intellectual functioning. Historically, we labeled individuals with this presentation of deficits as having mental retardation, but this term was changed to intellectual disability with the passage of Public Law 111-256, also called Rosa’s law, to combat stigmatization and misuse of the term. While the terms intellectual disability and intellectual developmental disorder are considered interchangeable, we will use intellectual developmental disorder in this book.

When considering intellectual developmental disorder there are two primary areas of major deficits – intellectual functioning (Criterion A) and adaptive functioning (Criterion B; APA, 2022). See Section 7.1.1.3 for a third criterion.

7.1.1.1. Intellectual functioning (Criterion A). Intellectual or cognitive functioning refers to our ability to problem solve, understand and analyze complex material, think abstractly, absorb information from our environment, learn from experience, plan, judge, and reason. Critical components include working memory, verbal comprehension, quantitative reasoning, cognitive efficacy, and perceptual reasoning. An individual with intellectual developmental disorder has a significant deficit in this area as confirmed by clinical assessment and individualized, standardized, culturally appropriate intelligence testing. The DSM-5-TR states that those with intellectual developmental disorder have scores approximately two standard deviations or more below the population mean. If a test has a standard deviation of 15 and a mean of 100, their scores will fall in the 65-75 range (70+5; APA, 2022).

7.1.1.2. Adaptive functioning (Criterion B). Adaptive skills are those that help us successfully navigate our daily lives. Our ability to understand safety signs in our environment, make appointments, interact with others, complete hygiene routines, etc. are examples of adaptive functioning. These are the skills one needs to live independently and be socially responsible. Individuals with intellectual developmental disorder typically have adaptive skills that are far below what is expected given their chronological age.

According to the DSM-5-TR (APA, 2022) adaptive functioning involves adaptive reasoning in three main domains: conceptual, social, and practical. First, the conceptual domain (also called the academic domain) involves competence in memory, language, math reasoning, problem-solving, etc. Second, the social domain involves being aware of the thoughts and feelings of other people, showing empathy, interpersonal communication skills, and social judgment, for example. Finally, the practical domain involves learning and self-management across life settings such as job responsibilities, personal care, and recreation. As you will see later, adaptive functioning is typically measured by standardized measures using knowledgeable informants and the individual, if possible.

7.1.1.3. Onset of intellectual developmental disorder (Criterion C). It should be noted that a third criterion must also be met– the onset of deficits described in criteria A and B must be present early in the neurodevelopmental period. As such, it is most frequently diagnosed in children. Intellectual developmental disorder is not something one would “acquire” in adulthood. If an individual experiences cognitive and adaptive function decline in later years, this is not considered intellectual developmental disorder (a neurodevelopmental disorder) but is more likely a neurocognitive disorder that may be due to a number of things such as traumatic brain injury or dementia. As such, although an individual can go undiagnosed until adulthood, and then as an adult be diagnosed with intellectual developmental disorder, there must be significant and undoubtable evidence of cognitive delay and adaptive functioning delay in the early developmental period. Otherwise, an adult would not be diagnosed with intellectual developmental disorder.

7.1.1.4. Severity specifiers. Rather than IQ scores, intellectual developmental disorder is assigned a severity specifier based on the level of delays related to adaptive functioning. Essentially, the more support someone needs, the more severe the intellectual disability. Severity ranges from Mild (least severe), to Moderate, to Severe, and Profound (most severe; APA, 2022). Severity is considered in relation to the three domains of conceptual, social, and practical. For instance, a specifier of severe would result the child having little understanding of written language or concepts involving numbers, quantity, and money (conceptual domain), speech and communication being focused on the here and now within everyday events (social domain), and not being able to make responsible decisions regarding the well-being of self or others, necessitating supervision at all times (practical domain).

7.1.1.5. Associated features. Individuals with intellectual developmental disorder have difficulties with social judgment, assessing risk, emotions, are gullible, and lack awareness. This can lead to increased rates of accidental injury, being exploited by others, possible victimization or physical and sexual abuse, and unintentional criminal involvement. They may also become distressed about their intellectual limitations (APA, 2022).

7.1.1.6. Clarification on nomenclature. The DSM-5-TR uses the term intellectual development disorder to clarify its relationship with the ICD-11 classification system which uses the term Disorders of Intellectual Development. The equivalent term of intellectual disability is placed in parentheses for continued use. It should be noted that both terms (i.e., intellectual developmental disorder and intellectual disability) are used in the medical and research literature, while the term intellectual disability is more commonly used by educators, advocacy groups, and the lay public.

7.1.2. Specific Learning Disorder

A specific learning disorder is characterized by persistent difficulties learning critical academic skills during the years of formal schooling such as reading of single words accurately and fluently or arithmetic calculation; performance of the affected academic skills being well below expected for age; learning difficulties being apparent in the early school years for most individuals, and that the learning difficulties are considered “specific” for four reasons. First, the learning difficulties are not better explained by intellectual developmental disorder, global developmental delay, hearing or vision disorders, or neurological or motor disorders. Second, they cannot be attributed to more general external factors such as economic or environmental disadvantage. Third, they cannot be attributed to neurological disorders such as a pediatric stroke, motor disorders, or to vision or hearing disorders. Fourth, a learning difficulty can be restricted to one academic skill or domain.

Historically, learning disorders were diagnosed when there was a significant discrepancy between an individual’s intellectual/cognitive ability (as measured by an intelligence test) and their academic achievement (as measured by a standardized achievement test) as this was required by DSM-IV-TR criteria. This method is referred to as the discrepancy model. While many still use this model, and nothing in the DSM-5-TR disallows it, the DSM-5 criteria were rewritten to allow more flexibility. Ultimately, a discrepancy between one’s IQ and academic achievement is no longer required; however, there must be specific data indicating an individual is preforming significantly below what would be expected given their chronological age.

In addition to significant academic deficits, there must be evidence that efforts (e.g., tutoring, increased and specialized instruction) to improve abilities within the specific area have been made before diagnosing a specific learning disorder. This is to ensure that an individual has had full access to educational material and supports before a professional assigns a learning disorder diagnosis to them. In school systems, this is where tiered interventions have come into play (more on this in Section 7.5).

7.1.2.1. Domain/subskill specific specifiers. Once an individual has been diagnosed with a learning disorder, all academic domains and subskills that have been impaired should be noted as follows:

- With impairment in reading – The individual has trouble comprehending material, reading fluently and quickly, or reading words accurately.

- With impairment in mathematics – The individual has trouble with number sense, memorization of arithmetic facts, math reasoning, and calculation.

- With impairment in written expression – The individual has trouble with accurately spelling words, using correct punctuation and grammar, or with writing clearly and organized.

7.1.2.2. Matters of dyslexia and dyscalculia. Technically, dyslexia and dyscalculia are not diagnoses in the DSM-5-TR, but are alternative terms used to describe learning disorders in reading (dyslexia) and math (dyscalculia). Dyslexia refers to a pattern of learning difficulties characterized by problems with accurate or fluent word recognition, decoding, and spelling (APA, 2022). Dyscalculia refers to a pattern of learning difficulties characterized by “problems processing numerical information, learning arithmetic facts, and performing accurate or fluent calculations” (APA, 2022, pg. 78).

Although these two terms are used very frequently in school systems and by professionals such as Speech/Language Pathologists, they are not diagnoses and are considered alternative terms in the DSM-5-TR. Instead, a mental health professional will diagnose a specific learning disorder with impairment in reading (for dyslexia) and a specific learning disorder with impairment in mathematics (for dyscalculia). This is an excellent example of how professionals will sometimes discuss the same phenomenon but use different terminology.

7.1.3. Differences and Similarities between the Disorders

Although intellectual developmental disorder and specific learning disorder may seem very similar, it is important not to confuse the two, as they are different. When thinking about both disorders, we have three distinct core areas to consider: adaptive functioning, cognitive/intellectual ability (IQ), and academic achievement. A rudimentarily way to think about this is with intellectual developmental disorder we are concerned with adaptive functioning and IQ, and with specific learning disorder we are concerned with IQ (sort of) and academic achievement. Although IQ matters (sort of) in both disorders, the reason it is important varies slightly. Because IQ is considered in both disorders, people often intertwine and confuse the two.

Let’s take a minute and think about this: IQ is what we are cognitively able to do – what we can do. Adaptive skills and academic achievement refer to what we are doing.

7.1.3.1 Intellectual developmental disorder. If we cannot perform in the average range on an IQ test and we are not performing daily living tasks appropriately (for our chronological age –we would not expect a 7-year-old to make their own doctor’s appointment but would expect them to know to dial 911 in an emergency), then this is indicative of intellectual developmental disorder (intellectual disability).

7.1.3.2. Specific learning disorder. To differentiate between a specific learning disorder and intellectual developmental disorder, it is useful to consider the discrepancy between what is expected of an individual (what they can do) and what they are doing. If an individual cannot perform averagely because their IQ is substantially below average, we could not expect them to perform at an average level on academic tasks. For example, if a person’s IQ is 70 and they cannot function typically on cognitive tasks, we would not expect them to achieve an academic score of 100, a 30-point jump from what they can do to what they are doing. If an individual has an IQ of 70, we would expect their academic score to be around 70, which would not necessarily indicate a specific learning disorder, even though the score is low. In this case, they would be performing as expected, so the low score achievement score would reflect low cognitive abilities resulting from intellectual development disorder. However, if there is a large discrepancy between what a person can do and what they are doing, for example, someone with an IQ of 100 scoring only a 70 in an academic achievement task, this could indicate a specific learning disorder.

7.1.3.3. Specific learning disorder in the cognitively delayed and in the cognitively gifted. Individuals with extreme cognitive functioning abilities are often overlooked. For example, children that are gifted, but have a reading disorder, often go undiagnosed because their deficits look like average abilities to others. Here is an example to illustrate this:

A 2nd grader with a high cognitive ability earns all As. She excels in math and writing. In fact, she is far past her peers in these areas. She has long learned her multiplication and division facts and is even working on some basic geometry skills. She can write and has been drafting paragraphs with ease and has even started learning to write essays. She loves math and writing, but she dislikes reading. When in class, she reads just like her peers, no more advanced, but right on 2nd grade level expectations. She finds reading to be more difficult, though, and it doesn’t come nearly as easy as math and writing. However, because she is on track compared to her peers, her teachers and parents do not recognize any issues – her grades are fine and her school standardized testing is not a problem.

What if you learned that her standardized math and writing scores matched her intellectual ability (meaning her can do and is doing matched) but her reading score (is doing), although average, is well below what would be expected given her IQ (can do) and is much lower than her math and writing scores, despite still being an acceptable score? Would you say she may have a reading disorder? If you said yes, you are right. If you said no, you may be right too. The fact is, this is a gray area. Previous versions of the DSM would have made it easy to diagnose this child with a learning disorder in reading. The DSM-5-TR makes it a bit tougher. If this reading deficit, compared to her own abilities, caused apparent impairment (internal distress, preventing her from advancing in math and writing because her reading abilities were lagging behind her other abilities), one would be inclined to diagnose her with a specific learning disorder in reading. However, one can see how this child could be overlooked and undiagnosed for years.

Now let’s reverse the scenario. A 2nd grade girl has a diagnosis of an intellectual developmental disorder (intellectual disability). She struggles in all areas of academics. However, her math abilities are even more behind than her reading and writing. Do you think one could make a case for a specific learning disorder in math? Theoretically, they could. But it takes a lot of careful documentation of intervention attempts (see RTI discussion) and standardized testing that makes it undoubtedly clear that this is true (similar to the above example).

When an individual has an IQ that lands in an extreme (low or high), their weaknesses are often missed. As such, providers and educators must be careful not overlook potential specific learning disorders in these individuals.

Key Takeaways

You should have learned the following in this section:

- Intellectual developmental disorder is characterized by intellectual functioning (Criterion A) and adaptive functioning (Criterion B) deficits and they must occur during the developmental period.

- Specifiers for intellectual developmental disorder indicate severity – mild, moderate, severe, or profound.

- A specific learning disorder is characterized by persistent difficulties learning critical academic skills during the years of formal schooling such as reading of single words accurately and fluently or arithmetic calculation; performance of the affected academic skills being well below expected for age; learning difficulties being apparent in the early school years for most individuals, and that the learning difficulties are considered “specific” (for four reasons).

- Specifiers for a specific learning disorder indicate if there is impairment in reading, mathematics, or written expression.

- Dyslexia and dyscalculia are not diagnoses in the DSM-5-TR but rather are alternative terms used to describe learning disorders in reading (dyslexia) and math (dyscalculia).

Section 7.1 Review Questions

- How does intellectual development disorder present and what specifiers are used?

- Why was the name intellectual development disorder chosen and what other name does it go by currently? What term was used previously and why has it been removed?

- How does specific learning disorder present and what specifiers are used?

- How are the two disorders both similar and different from one another?

7.2. Prevalence and Comorbidity

Section Learning Objectives

- Describe the prevalence and course of intellectual developmental disorder and specific learning disorder.

- Describe comorbid disorders of intellectual developmental disorder and specific learning disorder.

7.2.1. Intellectual Developmental Disorder

Intellectual development disorder occurs in approximately 1% of the overall general population while the global prevalence varies by country and level of development. Prevalence is 16 per 1,000 in middle-income countries but 9 per 1,000 in high-income countries (APA, 2022). Intellectual development disorder is more common in males than females, although sex ratios are inconsistent in the literature (APA, 2022; Einfeld & Emerson, 2008). It is hypothesized that the reason there is a higher occurrence of intellectual development disorder in males is due to general genetic vulnerability, often linked to X chromosome issues that males experience (Harris, 2006). Prevalence is higher in youth than in adults and there are no significant differences between ethnoracial groups.

Onset of intellectual development disorder is in the developmental period, though etiology and severity of brain dysfunction affect exact age and characteristic features at onset. For individuals with more severe intellectual development disorder, delayed motor, language, and social milestones are typical within the first 2 years of life. For individuals with mild intellectual development disorder, impairments may not be identifiable until school age when problems with academic learning are evident.

Intellectual development disorder is often comorbid with other medical and physical conditions as well as other neurodevelopmental conditions including autism and ADHD. Moreover, depression, bipolar, and anxiety disorders are often comorbid with intellectual development disorder. Impulse-control disorders, major neurocognitive disorder, and stereotypic movement disorder are frequently comorbid (APA, 2022)

7.2.2. Specific Learning Disorder

Specific learning disorder occurs in approximately 5 to 15% of school-age children in Brazil, Northern Ireland, and the United States. It is more common in males than females and suicidal thoughts and behavior were found in U.S. adolescents aged 15 years in public school presenting with poor reading ability (APA, 2022).

Onset, recognition, and diagnosis of specific learning disorder typically occur during the elementary school years as this is when children are required to read, spell, write, and learn mathematics. During early childhood and before the child starts school, there may be warning signs to include delays or deficits in language, problems with rhyming or counting, and issues related to fine motor skills needed for writing. Specific learning disorder is lifelong, though an individual may experience a persistent shifting array of learning difficulties across the lifespan. According to APA (2022), negative functional consequences occur across the lifespan and can include, “…lower academic attainment, higher rates of high school dropout, lower rates of postsecondary education, high levels of psychological distress and poorer overall mental health, higher rates of unemployment and underemployment, and lower incomes” (DSM-5-TR, pg. 84).

The different types of specific learning disorder are comorbid with one another (i.e., impairment in mathematics with reading), other neurodevelopmental disorders (e.g., ADHD, ASD, developmental coordination disorder, and communication disorders), anxiety disorders, behavioral problems, and depressive disorders.

Key Takeaways

You should have learned the following in this section:

- Intellectual development disorder occurs in approximately 1% of the overall general population while specific learning disorder occurs in approximately 5 to 15% of school-age children.

- Both disorders are more common in males than females.

- Onset of intellectual development disorder is in the developmental period, though etiology and severity of brain dysfunction affect exact age and characteristic features at onset.

- Onset, recognition, and diagnosis of specific learning disorder typically occur during the elementary school years.

- Intellectual development disorder is often comorbid with other medical and physical conditions, other neurodevelopmental conditions including autism and ADHD, and depression, bipolar, and anxiety disorders.

- Specific learning disorder is often comorbid with the different types of specific learning disorder, other neurodevelopmental disorders, developmental coordination disorder, and communication disorders, anxiety disorders, behavioral problems, and depressive disorders.

Section 7.2 Review Questions

- Are specific learning disorder or intellectual developmental disorder more common and which gender displays it at greater rates?

- When is the onset of both disorders?

- What other disorders are intellectual developmental disorder comorbid with?

- What other disorders are specific learning disorder comorbid with?

7.3. Etiology

Section Learning Objectives

- Describe biological basis/causes of intellectual developmental disorder and specific learning disorder.

- Describe environmental causes of intellectual developmental disorder and specific learning disorder.

7.3.1. Biological

7.3.1.1. Intellectual developmental disorder (intellectual disability). Biological factors heavily influence the development of intellectual developmental disorder. Genetic conditions (Kaufmann, Capone, Carter, & Lieberman, 2008) or brain malformations (Michelson et al., 2011) are important factors. Chromosomal differences and abnormalities, such as Fragile X syndrome and Downs syndrome, are heavily linked to intellectual developmental disorder (Harris, 2006). Additionally, brain and central nervous system malformations such as spina bifida are risk factors and correlated with intellectual developmental disorder (Harris, 2006).

7.3.1.2. Specific learning disorder. Heritability estimates have reached 50% in twin studies (Goldstein, Naglieri, & DeVries, 2011). Individuals are up to 10 times more likely to have specific learning disorder if one of their first relatives has a specific learning disorder as well (Shalev et al., 2001). In general, specific learning disorder development appears to be linked to neurological differences in the brain. However, specific information on the areas of the brain which are most impacted, and the specific central nervous system differences, are not well documented (Goldstein, et al., 2011).

7.3.2. Environmental

7.3.2.1. Intellectual developmental disorder. Risk factors include malnutrition of the mother during pregnancy or medical conditions preventing nutrition absorption of the fetus. Maternal illness or disease, such as diabetes or varicella (chickenpox), during pregnancy increases the risk of intellectual developmental disorder. Fetal exposure to alcohol, drugs, toxins, etc. also impacts potential development of intellectual developmental disorder. Events during labor and delivery or soon after delivery such as infant seizures, traumatic brain injuries, or infections (e.g., herpes simplex, measles, meningitis, malaria, or rubella) are related to the development of intellectual developmental disorder. Other events such as severe social deprivation, abuse, or exposure to high levels of lead or mercury raise the risk.

7.3.2.2. Specific learning disorder. Low birth weight (Aarnoudse-Moens, Weisglas-Kuperus, van Goudoever, & Oosterlaan, 2009) and fetal exposure to nicotine (Piper, Gray, & Birkett, 2012) are risk factors for developing a specific learning disorder. Early educational experiences may also heavily impact an individual’s neural development and neural connections (Goldstein, et al., 2011). For example, if an individual does not have proper exposure to educational materials early on, this may negatively impact the neural connections that are established, and thus, lead to a higher risk for developing specific learning disorder.

Key Takeaways

You should have learned the following in this section:

- Biological factors heavily influence the development of intellectual developmental disorder and include genetic conditions, brain malformations, chromosomal differences, and brain and central nervous system malformations.

- For specific learning disorder, heritability estimates have reached 50% in twin studies and neurological differences in the brain are linked to higher risk.

- Environmental risk factors for intellectual developmental disorder include malnutrition of the mother during pregnancy; medical conditions preventing nutrition absorption of the fetus; maternal illness or disease; fetal exposure to alcohol, drugs, and toxins; and events during labor and delivery or soon after delivery.

- Environmental risk factors for specific learning disorder include low birth weight, fetal exposure to nicotine, and early educational experiences.

Section 7.3 Review Questions

- What factors lead to a greater risk of developing intellectual developmental disorder?

- What factors lead to a greater risk of developing specific learning disorder?

7.4. Assessment

Section Learning Objectives

- Describe commonly used assessment tools.

7.4.1. Observations and Interviews

Although observation may be used for assessment of these disorders, it is the least clinically utilized. A school observation may be conducted to ensure other disorders are unnecessary to investigate (for example, ADHD) that may have explained some of the concerns from parents and educators. However, from a diagnostic standpoint, the most helpful information will be objective data (with some supplementation of information from interviews). Interviews are utilized to discover basic developmental information, history of learning skills and academic performance, developmental milestone achievement (e.g., when a child first walked, talked, etc.), and current adaptive functioning skills.

7.4.2. Objective Measures

7.4.2.1. Adaptive measures. We rely on standardized forms to assess individual’s adaptive functioning for many reasons. First, I (the first author) cannot begin to tell you how many first-time parents have looked at me and said, “My child isn’t doing X, Y, or Z, but she is my first child, so I’m not sure if she should be doing that yet or not.” Or, “I didn’t realize my (first) child was behind on certain skills until I had his sister, and his sister achieved these skills quicker/earlier than him (or has even passed him on some skills).” This is so common. Many parents are not sure how to compare their child’s abilities, because they simply do not have a comparison to use. Because of this, a simple verbal report of concerns of adaptive functioning is not reliable and always useful. Additionally, it is imperative to obtain information from multiple individuals to determine if the child is clinically behind. Objective data allows us to do this reliably and in a standardized manner. This is helpful because adaptive functioning can be very subjective. Common objective measures of adaptive functioning include the Adaptive Behavior Assessment System, 3rd edition (ABAS-3) and the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, 3rd edition (Vineland-3). These are both questionnaires and can be administered to parents as well as teachers.

7.4.2.2. Intellectual tests. Intellectual tests assess an individual’s cognitive functioning, also known as intelligence. We obtain an intelligence quotient (IQ) from these tests. IQ tests typically take anywhere between 1 to 1.5 hours. Although abbreviated forms of IQ tests exist, when examining an individual’s IQ for the purpose of understanding if cognitive or learning deficits are present, we want to utilize a full IQ battery and not an abbreviated version. Common IQ tests that are used include the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales, 5th edition (SB-5) Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, 5th edition (WISC-V), Woodcock Johnson Tests of Cognitive Abilities, 4th edition (WJ-IV), and the Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children, 2nd edition, Normative Update (KABC-II NU). Remember, this score tells us when an individual can do.

7.4.2.3. Academic achievement tests. Achievement tests assess academic achievement in an individual. We use these, instead of only looking at one’s grades, because it allows for a more consistent comparison. For example, if we only relied on grades, we would not be able to control for Teacher A’s grading or curriculum being more strict than Teacher B’s grading or curriculum. Using a standardize assessment gives us not only a more reliable, but also a more valid, assessment of where an individual is functioning, academically. Common tests include the Wechsler Individual Achievement Test, 3rd edition (WIAT-III), Woodcock Johnson Tests of Achievement, 4th edition (WJ-IV), and Kaufman Test of Educational Achievement, 3rd edition (KTEA-III). Remember, this score tells us what the individual is doing.

7.4.2.4. Records. Educational records including test grades, report cards, and standardized testing scores are utilized as well, but never on their own. Essentially, while this information is helpful, they cannot be used independently to determine if there is a clinical cognitive or learning deficit.

7.4.3. Response to Intervention (RTI)

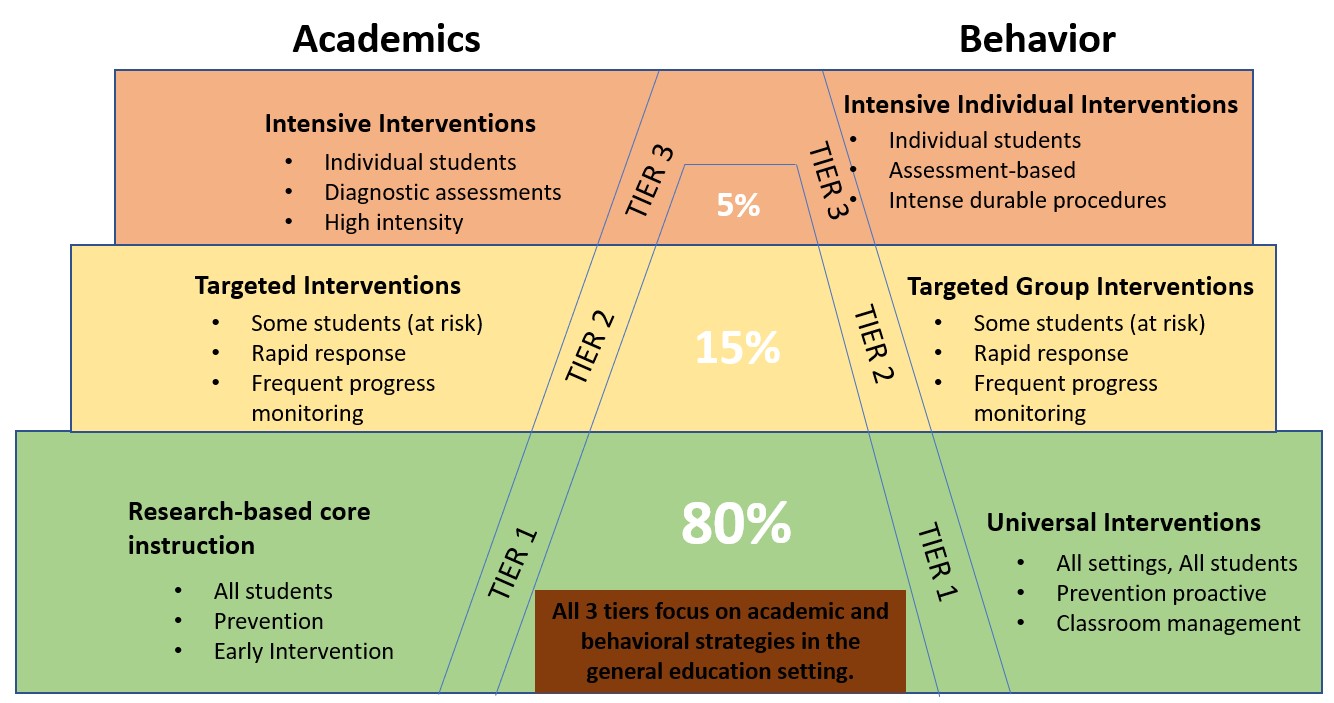

Response to Intervention, often referred to as RTI, is a systematic approach to assessing an individual’s ability to learn. This occurs in the school setting. The basic, general instruction all students receive is often referred to as Tier 1. If children begin to fall behind in academics in any area, they are identified and placed into a Tier 1 intervention group, or Tier 2 in the case that all students are already considered the Tier 1 group. If their learning and performance is remediated, they are transitioned out of this group. If their learning and performance is not mediated, they are transitioned into a Tier 2 intervention group. Again, if remediated, they transition down or out of tiered programing, and if they are not remediated, they transition to a Tier 3 group. If children are not remediated in a Tier 3 group, this is strong evidence of a learning disorder. Essentially, the child has been provided extensive, intense, and prolonged academic intervention, yet academic deficits are still notable. Tiered interventions involve very targeted interventions to improve academic performance. Tier 1 is the lowest level of intensity with Tier 3 being the highest. Curriculum-based measures of performance are used to screen all students, and then continually used with students who are channeled into the Tiered system. In Tier 2, small group instruction is typically utilized whereas in Tier 3 one-on-one instruction is commonly used. Figure 7.1 provides a helpful visualization of Tiered programming.

Figure 7.1. Tiered Programming

Note. Image adapted from Livingston Parish Publish Schools.

Key Takeaways

You should have learned the following in this section:

- A school observation may be conducted to ensure other disorders do not need to be investigated.

- Objective measures include adaptive measures, intellectual tests, academic achievement tests, and records.

- Responses to intervention (RTI) is a systematic approach to assessing an individual’s ability to learn and proceeds through a series of tiers.

Section 7.4 Review Questions

- Why is observation the least clinically utilized assessment tool?

- Why are objective measures the most useful assessment tool?

- What is Response to Intervention and how is it used?

7.5. Treatment

Section Learning Objectives

- Describe treatment options for intellectual developmental disorder and specific learning disorder.

7.5.1. Intellectual Developmental Disorder

7.5.1.1. Community supports and programs. For individuals with intellectual developmental disorder, community supports may be critical during childhood, and even more so as the individual transitions to adulthood. Community supports may include organizations devoted to socialization and family support. For example, The Arc is an incredible organization that is devoted to servicing individuals with developmental delays, including, but not limited to, intellectual developmental disorder. They often engage in advocacy efforts, offer training for the community and professionals, and employment services for individuals with intellectual developmental disorder or other developmental delays. Local chapters will often host social gatherings and events for individuals and their families (The Arc, 2018). Typically, there is an Arc chapter in most major cities and areas. Other community supports may involve government funded programming for living arrangements, supplemental income, etc.

As individuals transition to adulthood, some programming that may need to be considered is home/living arrangements. Historically, individuals with intellectual developmental disorder were often institutionalized. However, in recent years, a strong push to deinstitutionalize care, and provide group and community home options has occurred. As such, a more common and inclusive living option for individuals may be a group home in which multiple individuals live in a home-like setting with constant supervision, medical care access, and transportation. Another option, often referred to as supported independent living, is a situation in which fewer, such as four, individuals live in an apartment or similar setting, and are provided constant supervision by one individual. This is a less restrictive environment than a group home, as only one supervising staff is present, where nurses and other medical staff are not readily available. Moreover, individuals with intellectual developmental disorder are often capable of successful employment, and these opportunities are provided in group and independent living home arrangements. Individuals with intellectual developmental disorder, depending on the severity of their intellectual impairment, may work in settings with routine tasks (e.g., assembling plasticware packets, bussing tables) in independent settings (e.g., employed independently within the community) or in ‘supervised workshops’ (i.e., settings where multiple individuals with disabilities are employed and provided significant help and supervision while working).

7.5.1.2. Education. Individuals with intellectual developmental disorder receive an Individualized Education Plan (IEP) at their school, which is federally regulated and implemented at the state level, through the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) established in 2004 (IDEA, n.d.). This was enacted to ensure fair and equal access to public education for all children. An IEP outlines particular accommodations and supports things to which a child is entitled in the educational setting so they are able to access educational material to the fullest degree. Children with intellectual developmental disorder may receive typical academic instruction in an inclusion classroom, meaning they are in a general educational class. However, the more severe the disability, the more supports they may require. As such, this may mean the child is pulled out at periods of time to receive specialized instructions. If the child’s disability is severe, they may be placed in a self-contained classroom, which is a class with a small number of children who also have a severe disability, often with several teachers/teacher aids. Supports and accommodations may include reduced workloads, extended time to master material, increased instructional aid, etc. Additionally, supports may also extend beyond academic specific areas. For example, social skills may be a focus of intervention.

Eventually, a determination about whether or not to place an individual with severe deficits on a diploma track will be made. If an individual is not placed in a diploma track, they will receive a “certificate of completion” from high school, rather than a high school diploma. Non-diploma track supports might focus heavily on functional skills rather than traditional academics. For example, rather than worrying about mastering algebra, the individual’s education may focus on learning functional mathematics so that they will be able to successfully manage a grocery shopping trip/purchase.

Some college programs have been designed to allow individuals with developmental delays such as intellectual developmental disorder to access the college experience and receive specialized vocational instruction. For example, Mississippi State University’s ACCESS program (which is an acronym for Academics, Campus Life, Community Involvement, Employment Opportunities, Socialization, and Self-Awareness) is 4-year, non-degree program designed for individuals with a developmental delay, including intellectual developmental disorder. Students live on campus where they participate in the full college experience and receive a “Certification of Completion” within a specific vocational area when they finish the program (MSU, n.d.).

7.5.1.3. Psychotherapy. Although research has demonstrated the benefits of combined use of behavioral and cognitive-behavioral therapies, they are often underutilized in individuals with intellectual developmental disorder (Harris, 2006). Therapy often focuses on the emotional and behavioral impacts of intellectual developmental disorder, normalizing the individual’s experiences, and treating comorbid depression, anxiety, or other mental health conditions (Harris, 2006). Another strong area of focus may be increasing adaptive functioning skills. For example, helping the individual learn and regularly implement daily hygiene, chores, etc. and learning to navigate within their home and community safely and successfully may be a focus of therapy.

7.5.1.4. Medication. Medications to manage emotional or behavioral concerns occurring comorbid with an individual’s intellectual developmental disorder diagnosis may be beneficial. For example, if an individual has intellectual developmental disorder and depression, an antidepressant may be beneficial in helping to resolve some symptoms of depression. However, medications are not used to “treat” intellectual developmental disorder.

7.5.2. Specific Learning Disorder

7.5.2.1. Education. Individuals with specific learning disorder receive an Individualized Education Plan (IEP) as well. Focus is placed on increasing instructional aids for the child. The child will often be taken aside for additional, one-on-one interventions in the academic areas of concern. Additionally, the child may receive additional supports such as extended time on tests and assignments, partial credit (when partial credit is not typically given in a particular class), and early access to study guides or access to study guides even if one is not regularly given in a class. A child with a reading impairment may also be allowed to have tests read to them, especially on nonreading-related tests, such as history. The reason for doing this is so that the child’s performance in the nonreading-subject (e.g., science, history) is not negatively impacted by their reading deficit. The child may also be able to verbally respond to test items and have a teacher write their answers. The child may receive opportunities to correct errors on a test for additional credit, etc. These are some examples of accommodations and are not an exhaustive list. The accommodations and supports that are implemented should be specific to the child, their deficits, and their current needs.

Tutoring, whether in school or privately, is often useful as well. This increases exposure to material and provides additional support and intervention. Empirically based tutoring methods are sometimes used, particularly for children with dyslexia.

7.5.2.2. Medication. Like intellectual developmental disorder, medicine is not used to ‘treat’ specific learning disorder. However, given that ADHD is highly comorbid with specific learning disorder, ADHD-related medications may be beneficially utilized, when this comorbidity is present for a child. Moreover, as chronic underachievement in an academic area may lead to anxiety and depressive states for some children, medicinal intervention (or psychotherapy) may also be helpful.

Key Takeaways

You should have learned the following in this section:

- Treatment options for intellectual developmental disorder include community supports and programs, educational interventions such as IEPs, and psychotherapy.

- Treatment options for specific learning disorder include educational interventions such as IEPs and tutoring.

- Medicine is not utilized to ‘treat’ either disorder, but to manage emotional or behavioral concerns that are occurring comorbid with the two disorders.

Section 7.5 Review Questions

- What treatments exist for intellectual developmental disorder?

- What treatments exist for specific learning disorder?

- How is medicine used to treat both disorders?

Apply Your Knowledge

CASE VIGNETTE

Review these two cases:

- https://sites.google.com/site/kellyannelare/home/case-study-on-intellectual-disabilities/introducing-janetta

- https://ohioemploymentfirst.org/up_doc/Case_Study_Intellectual_Disability_accessible.pdf

QUESTIONS TO TEST YOUR KNOWLEDGE

- What ways were Janetta and Kesha’s experiences similar?

- What was the most notable take always from either Janetta or Kesha’s cases as they relate to our text?

- What are the key take-aways from how these disorders are addressed in the education setting?

Module Recap

In this module, we learned about intellectual developmental disorder (intellectual disability) and specific learning disorder. We discussed the various symptoms of both disorders and how they relate to the various presentations. We carefully examined the similarities and differences between intellectual developmental disorder and specific learning disorder as well. We then discussed the prevalence of these disorders, frequently comorbid disorders, and their etiology. We ended on a discussion of how intellectual developmental disorder and specific learning disorder are assessed and treated.

Next, we will learn about autism spectrum disorder. This is the second of three chapters in Part III: Developmental and Motor-related Disorders.

3rd edition