Module 15 – Trauma-related Disorders

3rd edition as of August 2022

Module Overview

In Module 15, we will discuss matters related to trauma- and stressor-related disorders to include their clinical presentation, prevalence, comorbidity, etiology, assessment, and treatment. Our discussion will include PTSD, acute stress disorder, and adjustment disorder. Prior to discussing these clinical disorders, we will explain what stressors are, as well as identify common stressors that may lead to a trauma- or stressor-related disorder. We will also discuss adverse childhood events and Children’s Advocacy Centers (CACs). Be sure you refer to Modules 1-3 for explanations of key terms (Module 1), an overview of models to explain psychopathology (Module 2), and descriptions of various therapies (Module 3).

Module Outline

- 15.1. Stressors and CACs

- 15.2. Clinical Presentation

- 15.3. Prevalence and Comorbidity

- 15.4. Etiology

- 15.5. Assessment

- 15.6. Treatment

Module Learning Outcomes

- Define and identify common stressors.

- Describe how trauma- and stressor-related disorders present.

- Describe the prevalence and comorbidity of trauma- and stressor-related disorders.

- Describe the etiology of trauma- and stressor-related disorders.

- Describe how trauma- and stressor-related disorders are assessed.

- Describe treatment options for trauma- and stressor-related disorders.

15.1. Stressors, ACEs, and CACs

Section Learning Objectives

- Define stressor and trauma.

- Identify and describe common stressors.

- Describe types of childhood trauma.

- Describe Adverse Childhood Events (ACE).

- Describe CACs.

15.1.1. Stressors and Types of Trauma

Before we dive into the clinical presentations of three of the trauma and stress-related disorders, let’s discuss common events that precipitate a stress-related diagnosis. A stress disorder occurs when an individual has difficulty coping with or adjusting to a recent stressor. Stressors can be any event—either witnessed firsthand, experienced personally, or experienced by a close family member—that increases physical or psychological demands on an individual. These events are significant enough that they pose a threat, whether real or imagined, to the individual. While many people experience similar stressors throughout their lives, only a small percentage of individuals experience significant maladjustment to the event that psychological intervention is warranted.

Among the most studied triggers for trauma-related disorders are combat and physical/sexual assault. Symptoms of combat-related trauma date back to World War I when soldiers would return home with “shell shock” (Figley, 1978). Unfortunately, it was not until after the Vietnam War that significant progress was made in both identifying and treating war-related psychological difficulties (Roy-Byrne et al., 2004). With the more recent wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, attention was again focused on posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms due to the large number of service members returning from deployments and reporting significant trauma symptoms.

Physical assault, and more specifically sexual assault, is another commonly studied traumatic event. Rape, or forced sexual intercourse or other sexual act committed without an individual’s consent, occurs in one out of every five women and one in every 71 men (Black et al., 2011). Unfortunately, this statistic likely underestimates the actual number of cases that occur due to the reluctance of many individuals to report their sexual assault. Of the reported cases, it is estimated that nearly 81% of female and 35% of male rape victims report both acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms (Black et al., 2011).

Specific to children, two thirds of children report experiencing at least one traumatic event by the time they reach age 16 (SAMHSA, 2017, December). To give a bit more clarity on the prevalence of traumatic events, 1 in 5 students are bullied and 1 in 6 are cyberbullied. Also, 54% of children have been impacted by a natural disaster and, in 2015, for every 1,000 children, 9.2 experienced either abuse or neglect (SAMHSA, 2017, December).

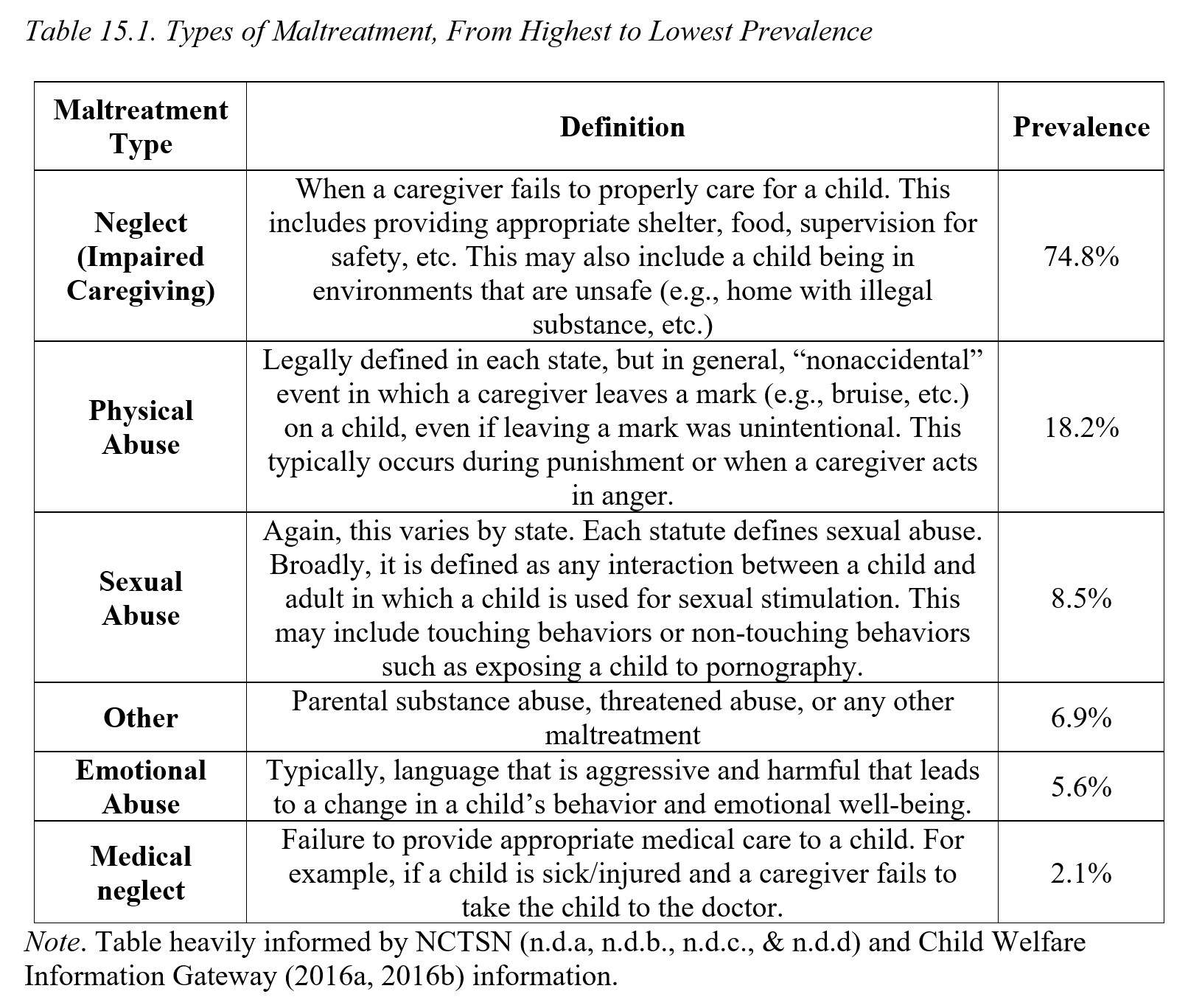

Trauma in childhood can take many different forms. Childhood trauma may either be a trauma that is unrelated to a specific event such as death of a loved one, a natural disaster, and other adverse childhood events (see ACE discussion below) or it may be specific to maltreatment. Childhood maltreatment refers to neglect or abuse of a child (Table 15.1 provides an overview of the various types of childhood maltreatment). Childhood trauma may include physical abuse, sexual abuse, neglect, medical trauma, witnessing domestic violence, traumatic grief, bullying, community violence, terrorism/violence, refugee trauma, natural disasters, complex trauma, early childhood trauma or any other life-threatening stressor. While some of these forms of abuse might seem clearly defined (e.g., physical abuse, sexual abuse, witnessing domestic violence), others may need a bit more clarification. For example, early childhood trauma (trauma that occurs prior to age 6) and complex trauma (exposure to multiple traumatic events) are not terms that are frequently mentioned in general societal conversations about childhood trauma. Neglect is the most common form of childhood maltreatment followed by physical abuse.

Early childhood trauma is trauma that occurs in very young children. Typically, people have a belief that if trauma occurs before a child can remember it, then it does not impact them. However, this is a misconception. Children’s brain structures may even be impacted such that their brain cortex may be reduced in size. It can also lead to significant disruptions in the attachment a child forms with their caregivers. Let’s think about why that might be. As an infant, our only responsibility is to grow (physically, cognitively, and emotionally) and we rely on caregivers to provide stability, protection, and soothing. When caregivers provide nurture, soothing, food, and stability to an infant, then the infant’s body can focus on making important neural connections, learning from their caregivers how to regulate their distress, and use the nurture and nutrition provided to physically and cognitively grow. However, if an infant does not feel safe and is not provided constant protection and care, they do not have the luxury of only focusing on growing and learning. The infant now must shift their attention from growing to surviving. They also do not learn how to sooth themselves or appropriately recognize danger (we tend to perceive benign things as dangerous in efforts to stay safe). They may struggle to regulate their emotions and behaviors, appropriately react to their environment and surroundings, and develop close and meaningful attachments (NCTSN, n.d.c.).

Complex trauma occurs when a child experiences multiple traumatic events. Those traumatic events are also interpersonal, meaning these events are directed at them from another person (typically the caregiver) and are not natural disasters or a painful medical procedure. The traumatic events are severe, and they impact the child’s development. The repeated events disrupt the child’s ability to feel secure with safety and stability. As such, their development is impacted. Because these children are often in a stress-activated state, their bodies do not appropriately regulate physiological responses to stress. They tend to recognize non-threating situations as threatening and others perceive them as “overreacting.” For example, a child that has been repeatedly abused by a caregiver may jump when their classmate slams their locker shut. Other children may perceive this child as overreacting and even point it out or make fun of him or her. However, for that child, his body is “stuck” in an overactive “flight or fight” state and perceived the small benign threat – a locker slamming – as a major threat. The constant stress the body is under can lead to physical difficulties and even a compromised immune system (NCTSN, n.d.c.).

Emotionally, children with a complex trauma history have a very difficult time recognizing, expressing, and regulating their emotions. They may also disassociate, often to cope with ongoing trauma. Their ability to attach to caregivers may also be compromised (NCTSN, n.d.c.).

Behaviorally, they may be “set off” easily and struggle to regulate their own behaviors and reactions. They may appear impulsive and unpredictable. They may attempt to exert control in their environment which may lead to behavioral disturbances as well. Moreover, children with this history may have trouble with problem-solving and acquiring new cognitive skills (NCTSN, n.d.c.).

15.1.2. Adverse Childhood Events (ACE)

Kaiser Permanente conducted a massive study in the years of 1995 to 1997 (Felitti, Anda, Nordenberg, Williamson, Spitz, Edwards, & Marks, 1998). The study focused on various adverse childhood experiences and how those experiences impacted children’s overall development. They divided adverse childhood events into 2 main areas (i.e., abuse and household dysfunction) with seven separate categories: psychological abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, substance abuse in the home, mental illness of a household member, violent behavior by mother, and criminal behavior of a household member. The study was groundbreaking. The results of the study found that over half of the participants had experienced at least one major childhood adverse event. Moreover, about a quarter of participants had experienced two separate types of adverse events. With increased adverse events, adult outcomes were increasingly negative such that more adverse events lead to higher likelihood of smoking, increased sexual partners and sexually transmitted disease, obesity, and other health concerns (Felitti, et al., 1998). This study made it clear that adverse events have long-lasting impacts into adulthood that impact overall health and quality of life. As such, the need to implement prevention efforts to reduce the frequency in which children experience adverse events, including maltreatment and neglect, was obvious.

15.1.3 Children’s Advocacy Centers (CACs)

Children’s Advocacy Centers (CACs) are designed to improve a child’s experience with investigations following abuse. The first CAC was established in 1985. Before CACs, children would have to disclose their abuse to several different individuals (e.g., first the police, then a doctor, then a social worker, investigator, and counselor). With the implementation of a CAC, multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) were designed. MDTs are comprised of several professionals including but limited to law enforcement, medical professionals, mental health providers, child protective services, victim advocates, and legal prosecutors. The idea was that a child would complete one forensic interview with multiple team members viewing the interview (either live or videoed). A forensic interview is a recorded interview with the goal to allow a child to provide information about their experiences of abuse in a non-leading and supportive method (National Children’s Advocacy Center, n.d.). The forensic interview is conducted by a trained individual and is videotaped so that it can be used in litigation and does not require the child to testify or recount abuse in court. This reduced the number of times that a child had to disclose their abuse/trauma, on average from 8 different people to just 1 time. CACs appear to improve a child and caregivers’ satisfaction with the investigation process (Jones, Cross, Walsh, Simone, 2007). The CAC team also works to connect the child and family with mental health and other needed or appropriate support services following their initial contact.

Now that we’ve discussed a little about some of the most commonly studied traumatic events, let’s take a look further at the presentation and diagnostic criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder, acute stress disorder, and adjustment disorder.

Key Takeaways

You should have learned the following in this section:

- A stressor is any event that increases physical or psychological demands on an individual.

- It does not have to be personally experienced but can be witnessed or occur to a close family member or friend to have the same effect.

- Only a small percentage of people experience significant maladjustment due to these events.

- The most studied triggers for trauma-related disorders include physical/sexual assault and combat.

- Adverse events have long-lasting impacts into adulthood that impact overall health and quality of life.

- Children’s Advocacy Centers (CACs) are designed to improve a child’s experience with investigations following abuse.

- A forensic interview is a recorded interview with the goal to allow a child to provide information about their experiences of abuse in a non-leading and supportive method

Section 15.1 Review Questions

- Given an example of a stressor you have experienced in your own life.

- Why are the triggers of physical/sexual assault and combat more likely to lead to a trauma-related disorder?

- What forms does childhood trauma take?

- What are CACs?

- What is the principal tool used by CACs?

15.2. Clinical Presentation

Section Learning Objectives

- Describe how PTSD presents (take note of differences for children 6 and younger)

- Describe how acute stress disorder presents.

- Describe how adjustment disorder presents.

15.2.1. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Posttraumatic stress disorder, or more commonly known as PTSD, is identified by the development of physiological, psychological, and emotional symptoms following exposure to a traumatic event. Individuals must have been exposed to a situation where actual or threatened death, sexual violence, or serious injury occurred. Examples of these situations include but are not limited to witnessing a traumatic event as it occurred to someone else; learning about a traumatic event that occurred to a family member or close friend; directly experiencing a traumatic event; or being exposed to repeated events where one experiences an aversive event (e.g., victims of child abuse/neglect, ER physicians in trauma centers, etc.).

It is important to understand that while the presentation of these symptoms varies among individuals, to meet the criteria for a diagnosis of PTSD, individuals need to report symptoms among the four different categories of symptoms.

15.2.1.1. Category 1: Recurrent experiences. The first category involves recurrent experiences of the traumatic event, which can occur via dissociative reactions such as flashbacks; recurrent, involuntary, and intrusive distressing memories; or even recurrent distressing dreams (APA, 2022, pgs. 301-2). These recurrent experiences must be specific to the traumatic event or the moments immediately following to meet the criteria for PTSD. Regardless of the method, the recurrent experiences can last several seconds or extend for several days. They are often initiated by physical sensations similar to those experienced during the traumatic events or environmental triggers such as a specific location. Because of these triggers, individuals with PTSD are known to avoid stimuli (i.e., activities, objects, people, etc.) associated with the traumatic event. One or more of the intrusion symptoms must be present.

15.2.1.2. Category 2: Avoidance of stimuli. The second category involves avoidance of stimuli related to the traumatic event and either one or both of the following must be present. First, individuals with PTSD may be observed trying to avoid the distressing thoughts, memories, and/or feelings related to the memories of the traumatic event. Second, they may prevent these memories from occurring by avoiding physical stimuli such as locations, individuals, activities, or even specific situations that trigger the memory of the traumatic event.

15.2.1.3. Category 3: Negative alterations in cognition or mood. The third category experienced by individuals with PTSD is negative alterations in cognition or mood and at least two of the symptoms described below must be present. This is often reported as difficulty remembering an important aspect of the traumatic event. It should be noted that this amnesia is not due to a head injury, loss of consciousness, or substances, but rather, due to the traumatic nature of the event. The impaired memory may also lead individuals to have false beliefs about the causes of the traumatic event, often blaming themselves or others. An overall persistent negative state, including a generalized negative belief about oneself or others is also reported by those with PTSD. Similar to those with depression, individuals with PTSD may report a reduced interest in participating in previously enjoyable activities, as well as the desire to engage with others socially. They also report not being able to experience positive emotions.

15.2.1.4. Category 4: Alterations in arousal and reactivity. The fourth and final category is alterations in arousal and reactivity and at least two of the symptoms described below must be present. Because of the negative mood and increased irritability, individuals with PTSD may be quick-tempered and act out aggressively, both verbally and physically. While these aggressive responses may be provoked, they are also sometimes unprovoked. It is believed these behaviors occur due to the heightened sensitivity to potential threats, especially if the threat is similar to their traumatic event. More specifically, individuals with PTSD have a heightened startle response and easily jump or respond to unexpected noises just as a telephone ringing or a car backfiring. They also experience significant sleep disturbances, with difficulty falling asleep, as well as staying asleep due to nightmares; engage in reckless or self-destructive behavior, and have problems concentrating.

Although somewhat obvious, these symptoms likely cause significant distress in social, occupational, and other (i.e., romantic, personal) areas of functioning. Duration of symptoms is also important, as PTSD cannot be diagnosed unless symptoms have been present for at least one month. If symptoms have not been present for a month, the individual may meet criteria for acute stress disorder (see below).

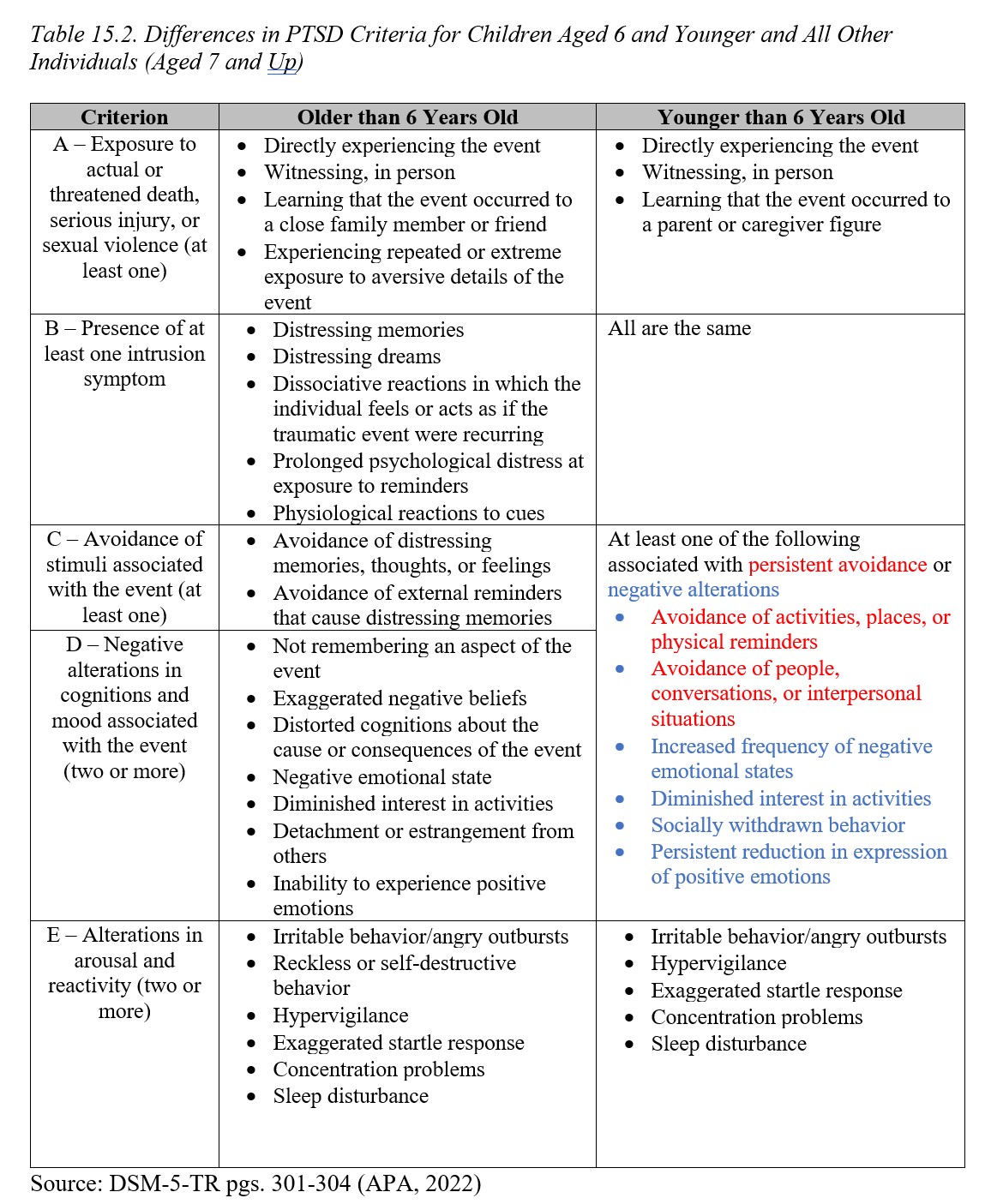

15.2.1.5. Diagnosing PTSD in children under 6 years of age. Historically, diagnosing PTSD in children was difficult. The criteria required the presence of internal symptoms that children sometimes have difficulty reporting and describing. For example, assessing if a child has persistent negative beliefs about a traumatic event or about themselves, or has difficulty with remembering aspects of the event was difficult. As such, when the new DSM-5 was published, the taskforce created new criteria for younger children (aged 6 and under).

While some of the specific criteria are the same, such as experiencing a traumatic event, other components are different. To better understand the differences, see Table 15.2 below:

15.2.2. Acute Stress Disorder

Acute stress disorder is very similar to PTSD except for the fact that symptoms must be present from 3 days to 1 month following exposure to one or more traumatic events. If the symptoms are present after one month, the individual would then meet the criteria for PTSD. Additionally, if symptoms present immediately following the traumatic event but resolve by day 3, an individual would not meet the criteria for acute stress disorder.

Symptoms of acute stress disorder follow that of PTSD with a few exceptions. PTSD requires symptoms within each of the four categories discussed above; however, acute stress disorder requires that the individual experience nine symptoms across five different categories (intrusion symptoms, negative mood, dissociative symptoms, avoidance symptoms, and arousal symptoms; note that in total, there are 14 symptoms across these five categories). For example, an individual may experience several arousal and reactivity symptoms such as sleep issues, concentration issues, and hypervigilance, but does not experience issues regarding negative mood. Regardless of the category of the symptoms, so long as nine symptoms are present and the symptoms cause significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, and other functioning, an individual will meet the criteria for acute stress disorder.

Making Sense of the Disorders

In relation to trauma- and stressor-related disorders, note the following:

- Diagnosis PTSD …… if symptoms have been experienced for at least one month

- Diagnosis acute stress disorder … if symptoms have been experienced for 3 days to one month

15.2.3. Adjustment Disorder

Adjustment disorder is the least intense of the three disorders discussed so far in this module. An adjustment disorder occurs following an identifiable stressor that happened within the past 3 months. This stressor can be a single event (loss of job, death of a family member) or a series of multiple stressors (cancer treatment, divorce/child custody issues).

Unlike PTSD and acute stress disorder, adjustment disorder does not have a set of specific symptoms an individual must meet for diagnosis. Rather, whatever symptoms the individual is experiencing must be related to the stressor and must be significant enough to impair social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning and causes marked distress “…that is out of proportion to the severity or intensity of the stressor” (APA, 2022, pg. 319).

It should be noted that there are modifiers associated with adjustment disorder. Due to the variety of behavioral and emotional symptoms that can be present with an adjustment disorder, clinicians are expected to classify a patient’s adjustment disorder as one of the following: with depressed mood, with anxiety, with mixed anxiety and depressed mood, with disturbance of conduct, with mixed disturbance of emotions and conduct, or unspecified if the behaviors do not meet criteria for one of the aforementioned categories. Based on the individual’s presenting symptoms, the clinician will determine which category best classifies the patient’s condition. These modifiers are also important when choosing treatment options for patients.

Key Takeaways

You should have learned the following in this section:

- In terms of stress disorders, symptoms lasting over 3 days but not exceeding one month, would be classified as acute stress disorder while those lasting over a month are typical of PTSD.

- If symptoms begin after a traumatic event but resolve themselves within three days, the individual does not meet the criteria for a stress disorder.

- Symptoms of PTSD fall into four different categories for which an individual must have at least one symptom in each category to receive a diagnosis. These categories include recurrent experiences, avoidance of stimuli, negative alterations in cognition or mood, and alterations in arousal and reactivity.

- To receive a diagnosis of acute stress disorder an individual must experience nine symptoms across five different categories (intrusion symptoms, negative mood, dissociative symptoms, avoidance symptoms, and arousal symptoms).

- Adjustment disorder is the last intense of the three disorders and does not have a specific set of symptoms of which an individual has to have some number. Whatever symptoms the person presents with, they must cause significant impairment in areas of functioning such as social or occupational, and several modifiers are associated with the disorder.

Section 15.2 Review Questions

- What is the difference in diagnostic criteria for PTSD, acute stress disorder, and adjustment disorder?

- What are the four categories of symptoms for PTSD? How do these symptoms present in acute stress disorder and adjustment disorder?

15.3. Prevalence and Comorbidity

Section Learning Objectives

- Describe the prevalence and comorbidity of PTSD.

- Describe the prevalence and comorbidity of acute stress disorder.

- Describe the prevalence and comorbidity of adjustment disorders.

15.3.1. PTSD

15.3.1.1. Prevalence. The national lifetime prevalence rate for PTSD using DSM-IV criteria is 6.8% for U.S. adults and 5.0% to 8.1% for U.S. adolescents. There are currently no definitive, comprehensive population-based data using DSM-5 though studies are beginning to emerge (APA, 2022). It should not come as a surprise that the rates of PTSD are higher among veterans and others who work in fields with high traumatic experiences (i.e., firefighters, police, EMTs, emergency room providers). In fact, PTSD rates for combat veterans are estimated to be as high as 30% (NcNally, 2012). Between one-third and one-half of all PTSD cases consist of rape survivors, military combat and captivity, and ethnically or politically motivated genocide (APA, 2022).

Concerning gender, PTSD is more prevalent among females (8% to 11%) than males (4.1% to 5.4%), likely due to their higher occurrence of exposure to traumatic experiences such as childhood sexual abuse, rape, domestic abuse, and other forms of interpersonal violence. Women also experience PTSD for a longer duration. (APA, 2022). Gender differences are not found in populations where both males and females are exposed to significant stressors suggesting that both genders are equally predisposed to developing PTSD. Prevalence rates vary slightly across cultural groups, which may reflect differences in exposure to traumatic events. More specifically, prevalence rates of PTSD are highest for African Americans, followed by Latinx Americans and European Americans, and lowest for Asian Americans (Hinton & Lewis-Fernandez, 2011). According to the DSM-5-TR, there are higher rates of PTSD among Latinx, African-Americans, and American Indians compared to whites, and likely due to exposure to past adversity and racism and discrimination (APA, 2022).

15.3.1.2. Comorbidity. Given the traumatic nature of the disorder, it should not be surprising that there is a high comorbidity rate between PTSD and other psychological disorders. Individuals with PTSD are more likely than those without PTSD to report clinically significant levels of depressive, bipolar, anxiety, or substance abuse-related symptoms (APA, 2022). There is also a strong relationship between PTSD and major neurocognitive disorders, which may be due to the overlapping symptoms between these disorders.

15.3.2. Acute Stress Disorder

15.3.2.1. Prevalence. The prevalence rate for acute stress disorder varies across the country and by traumatic event. Accurate prevalence rates for acute stress disorder are difficult to determine as patients must seek treatment within 30 days of the traumatic event. Despite that, it is estimated that anywhere between 7-30% of individuals experiencing a traumatic event will develop acute stress disorder (National Center for PTSD). While acute stress disorder is not a good predictor of who will develop PTSD, approximately 50% of those with acute stress disorder do eventually develop PTSD (Bryant, 2010; Bryant, Friedman, Speigel, Ursano, & Strain, 2010).

As with PTSD, acute stress disorder is more common in females than males; however, unlike PTSD, there may be some neurobiological differences in the stress response, gender differences in the emotional and cognitive processing of trauma, and sociocultural factors that contribute to females developing acute stress disorder more often than males (APA, 2022). With that said, the increased exposure to traumatic events among females may also be a strong reason why women are more likely to develop acute stress disorder.

15.3.2.2. Comorbidity. Because 30 days after the traumatic event, acute stress disorder becomes PTSD (or the symptoms remit), the comorbidity of acute stress disorder with other psychological disorders has not been studied. While acute stress disorder and PTSD cannot be comorbid disorders, several studies have explored the relationship between the disorders to identify individuals most at risk for developing PTSD. The literature indicates roughly 80% of motor vehicle accident survivors, as well as assault victims, who met the criteria for acute stress disorder went on to develop PTSD (Brewin, Andrews, Rose, & Kirk, 1999; Bryant & Harvey, 1998; Harvey & Bryant, 1998). While some researchers indicated acute stress disorder is a good predictor of PTSD, others argue further research between the two and confounding variables should be explored to establish more consistent findings.

15.3.3. Adjustment Disorder

15.3.3.1. Prevalence. Adjustment disorders are relatively common as they describe individuals who are having difficulty adjusting to life after a significant stressor. In psychiatric hospitals in the U.S., Australia, Canada, and Israel, adjustment disorders accounted for roughly 50% of the admissions in the 1990s. It is estimated that anywhere from 5-20% of individuals in outpatient mental health treatment facilities have an adjustment disorder as their principal diagnosis. Adjustment disorder has been found to be higher in women than men (APA, 2022).

15.3.3.2. Comorbidity. Unlike most of the disorders we have reviewed thus far, adjustment disorders have a high comorbidity rate with various other medical conditions (APA, 2022). Often following a critical or terminal medical diagnosis, an individual will meet the criteria for adjustment disorder as they process the news about their health and the impact their new medical diagnosis will have on their life. Other psychological disorders are also diagnosed with adjustment disorder; however, symptoms of adjustment disorder must be met independently of the other psychological condition. For example, an individual with adjustment disorder with depressive mood must not meet the criteria for a major depressive episode; otherwise, the diagnosis of MDD should be made over adjustment disorder. As the DSM-5-TR says, “adjustment disorders are common accompaniments of medical illness and may be the major psychological response to a medical condition” (APA, 2022).

Key Takeaways

You should have learned the following in this section:

- Regarding PTSD, rates are highest among people who are likely to be exposed to high traumatic events, women, and minorities.

- As for acute stress disorder, prevalence rates are hard to determine since patients must seek medical treatment within 30 days, but females are more likely to develop the disorder.

- Adjustment disorders are relatively common since they occur in individuals having trouble adjusting to a significant stressor, though women tend to receive a diagnosis more than men.

- PTSD has a high comorbidity rate with psychological and neurocognitive disorders while this rate is hard to establish with acute stress disorder since it becomes PTSD after 30 days.

- Adjustment disorder has a high comorbidity rate with other medical conditions as people process news about their health and what the impact of a new medical diagnosis will be on their life.

Section 15.3 Review Questions

- Compare and contrast the prevalence rates among the trauma and stress-related disorders.

- What are the most common comorbidities among trauma and stress-related disorders?

- Why is it hard to establish comorbidities for acute stress disorder?

15.4. Etiology

Section Learning Objectives

- Describe the biological causes of trauma- and stressor-related disorders.

- Describe the cognitive causes of trauma- and stressor-related disorders.

- Describe the social causes of trauma- and stressor-related disorders.

- Describe the sociocultural causes of trauma- and stressor-related disorders.

15.4.1. Biological

HPA axis. One theory for the development of trauma and stress-related disorders is the over-involvement of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. The HPA axis is involved in the fear-producing response, and some speculate that dysfunction within this axis is to blame for the development of trauma symptoms. Within the brain, the amygdala serves as the integrative system that inherently elicits the physiological response to a traumatic/stressful environmental situation. The amygdala sends this response to the HPA axis to prepare the body for “fight or flight.” The HPA axis then releases hormones—epinephrine and cortisol—to help the body to prepare to respond to a dangerous situation (Stahl & Wise, 2008). While epinephrine is known to cause physiological symptoms such as increased blood pressure, increased heart rate, increased alertness, and increased muscle tension, to name a few, cortisol is responsible for returning the body to homeostasis once the dangerous situation is resolved.

Researchers have studied the amygdala and HPA axis in individuals with PTSD, and have identified heightened amygdala reactivity in stressful situations, as well as excessive responsiveness to stimuli that is related to one’s specific traumatic event (Sherin & Nemeroff, 2011). Additionally, studies have indicated that individuals with PTSD also show a diminished fear extinction, suggesting an overall higher level of stress during non-stressful times. These findings may explain why individuals with PTSD experience an increased startle response and exaggerated sensitivity to stimuli associated with their trauma (Schmidt, Kaltwasser, & Wotjak, 2013).

15.4.2. Cognitive

Preexisting conditions of depression or anxiety may predispose an individual to develop PTSD or other stress disorders. One theory is that these individuals may ruminate or over-analyze the traumatic event, thus bringing more attention to the traumatic event and leading to the development of stress-related symptoms. Furthermore, negative cognitive styles or maladjusted thoughts about themselves and the environment may also contribute to PTSD symptoms. For example, individuals who identify life events as “out of their control” report more severe stress symptoms than those who feel as though they have some control over their lives (Catanesi et al., 2013).

15.4.3. Social

While this may hold for many psychological disorders, social and family support have been identified as protective factors for individuals prone to develop PTSD. More specifically, rape victims who are loved and cared for by their friends and family members as opposed to being judged for their actions before the rape, report fewer trauma symptoms and faster psychological improvement (Street et al., 2011).

15.4.4. Sociocultural

As was mentioned previously, different ethnicities report different prevalence rates of PTSD. While this may be due to increased exposure to traumatic events, there is some evidence to suggest that cultural groups also interpret traumatic events differently, and therefore, may be more vulnerable to the disorder. Hispanic Americans have routinely been identified as a cultural group that experiences a higher rate of PTSD. Studies ranging from combat-related PTSD to on-duty police officer stress, as well as stress from a natural disaster, all identify Hispanic Americans as the cultural group experiencing the most traumatic symptoms (Kaczkurkin et al., 2016; Perilla et al., 2002; Pole et al., 2001).

Women also report a higher incidence of PTSD symptoms than men. Some possible explanations for this discrepancy are stigmas related to seeking psychological treatment, as well as a greater risk of exposure to traumatic events that are associated with PTSD (Kubiak, 2006). Studies exploring rates of PTSD symptoms for military and police veterans have failed to report a significant gender difference in the diagnosis rate of PTSD suggesting that there is not a difference in the rate of occurrence of PTSD in males and females in these settings (Maguen, Luxton, Skopp, & Madden, 2012).

Key Takeaways

You should have learned the following in this section:

- In terms of causes for trauma- and stressor-related disorders, an over-involvement of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis has been cited as a biological cause, with rumination and negative coping styles or maladjusted thoughts emerging as cognitive causes.

- Culture may lead to different interpretations of traumatic events thus causing higher rates among Hispanic Americans.

- Social and family support have been found to be protective factors for individuals most likely to develop PTSD.

Section 15.4 Review Questions

- Discuss the four etiological models of the trauma- and stressor-related disorders. Which model best explains the maintenance of trauma/stress symptoms? Which identifies protective factors for the individual?

15.5. Assessment

Section Learning Objectives

- Outline the assessment process when screening for trauma experiences and PTSD.

Overall, every child should be screened for trauma experiences despite the setting. If a clinician sees a child that is being assessed for ADHD, they should still screen for trauma. This is because we never know when a child may disclose a trauma, and trauma and PTSD reactions may explain some behaviors. For example, is the child impulsive and explosive due to a behavioral disorder such as ADHD or are they experiencing hyper-arousal and emotion regulation difficulties associated with a complex trauma history and/or PTSD? This question cannot be answered if the clinician does not screen for trauma.

When assessing for PTSD, two questions must be answered: (1) has a trauma occurred and (2) is the child exhibiting trauma reactions/symptoms? To answer the first part, has a trauma occurred, a trauma screening is utilized. Screening for trauma can be formal or informal. Utilizing a standard trauma screener can be helpful so that a provider does not fail to screen for a particular type of trauma. For example, the Childhood Trust Events Inventory screens for various types of traumas and takes only a few minutes to complete. The UCLA PTSD Reaction Index for DSM-5 also has a helpful trauma screener at the beginning of the measure. Trauma screening is often done directly with a child but can also be used with caregivers or other adults involved in the child’s life (e.g., social worker, case worker).

To answer the second part, is the child exhibiting trauma reactions/symptoms, we must understand if there is a presence of avoidance behaviors, intrusive memories, hyperarousal, irritability, behavioral regulation difficulties, interpersonal difficulties, or developmental problems. We can do this by interviewing the child, parent, or other adults. We can also use objective measures that assess these areas. For example, the Trauma Symptom Checklist for Young Children (TSCYC, caregiver report) and the Trauma Symptom Checklist for Children (TSCC, child report) can be used to assess for general, related symptoms. The UCLA PTSD Reaction Index for DSM-5 can be used to assess for the presence of specific criteria of PTSD to understand the likelihood the child meets full DSM-5 criteria of PTSD.

An alternative option that may also be helpful is to create a timeline with the adults involved in the child’s life to understand when traumatic events occurred and when symptoms started. This helps mental health practitioners understand if the symptoms are related to a trauma or not. For example, if a child presents as irritable and moody prior to any trauma, the irritability may not necessarily be a trauma-reaction. Conversely, if a child was happy and did not display frequent irritability but following a trauma presented with significant irritability, this may be indicative of a trauma reaction. Thus, building a timeline with the caregiver can be helpful. Utilizing a timeline with a child, however, is not suggested as this may be too distressing for them.

Key Takeaways

You should have learned the following in this section:

- When assessing for PTSD, two questions must be answered: (1) has a trauma occurred and (2) is the child exhibiting trauma reactions/symptoms?

- To answer the first part, has a trauma occurred, a trauma screening is utilized.

- To answer the second part, is the child exhibiting trauma reactions/symptoms, we must understand if there is a presence of avoidance behaviors, intrusive memories, hyperarousal, irritability, behavioral regulation difficulties, interpersonal difficulties, or developmental problems.

- An alternative option that may also be helpful is to create a timeline with the adults involved in the child’s life to understand when traumatic events occurred and when symptoms started.

Section 15.5 Review Questions

- What tools are used to assess for PTSD in children?

- How might a timeline be used and with whom?

15.6. Treatment

Section Learning Objectives

- Describe the treatment approach of the psychological debriefing.

- Describe the treatment approach of exposure therapy.

- Describe the treatment approach of CBT.

- Describe the treatment approach of other psychological interventions.

- Describe the treatment approach of parent-child interventions.

- Describe the use of psychopharmacological treatment.

15.6.1. Psychological Debriefing

One way to negate the potential development of PTSD symptoms is thorough psychological debriefing. Psychological debriefing is considered a type of crisis intervention that requires individuals who have recently experienced a traumatic event to discuss or process their thoughts and feelings related to the traumatic event, typically within 72 hours of the event (Kinchin, 2007). While there are a few different methods to a psychological debriefing, they all follow the same general format:

- Identifying the facts (what happened?)

- Evaluating the individual’s thoughts and emotional reaction to the events leading up to the event, during the event, and then immediately following

- Normalizing the individual’s reaction to the event

- Discussing how to cope with these thoughts and feelings, as well as creating a designated social support system (Kinchin, 2007).

Throughout the last few decades, there has been a debate on the effectiveness of psychological debriefing. Those within the field argue that psychological debriefing is not a means to cure or prevent PTSD, but rather, psychological debriefing is a means to assist individuals with a faster recovery time posttraumatic event (Kinchin, 2007). Research across a variety of traumatic events (i.e., natural disasters, burns, war) routinely suggests that psychological debriefing is not helpful in either the reduction of posttraumatic symptoms nor the recovery time of those with PTSD (Tuckey & Scott, 2014). One theory is these early interventions may encourage patients to ruminate on their symptoms or the event itself, thus maintaining PTSD symptoms (McNally, 2004). In efforts to combat these negative findings of psychological debriefing, there has been a large movement to provide more structure and training for professionals employing psychological debriefing, thus ensuring that those who are providing treatment are properly trained to do so.

While this might be used in instances of natural disasters and mass traumas, this is not commonly used with children. As such, it is important to understand debriefing and the varying options, but it is not necessary to understand the intricacies of debriefing.

15.6.2. Exposure Therapy

While exposure therapy is predominately used in anxiety disorders, it has also shown great success in treating PTSD-related symptoms as it helps individuals extinguish fears associated with the traumatic event. There are several different types of exposure techniques—imaginal, in vivo, and flooding are among the most common types (Cahill, Rothbaum, Resick, & Follette, 2009).

In imaginal exposure, the individual mentally re-creates specific details of the traumatic event. The patient is then asked to repeatedly discuss the event in increasing detail, providing more information regarding their thoughts and feelings at each step of the event. During in vivo exposure, the individual is reminded of the traumatic event through the use of videos, images, or other tangible objects related to the traumatic event that induces a heightened arousal response. While the patient is re-experiencing cognitions, emotions, and physiological symptoms related to the traumatic experience, they are encouraged to utilize positive coping strategies, such as relaxation techniques, to reduce their overall level of anxiety.

Imaginal exposure and in vivo exposure are generally done in a gradual process, with imaginal exposure beginning with fewer details of the event, and slowly gaining information over time. In vivo starts with images or videos that elicit lower levels of anxiety, and then the patient slowly works their way up a fear hierarchy, until they are able to be exposed to the most distressing images. Another type of exposure therapy, flooding, involves disregard for the fear hierarchy, presenting the most distressing memories or images at the beginning of treatment. While some argue that this is a more effective method, it is also the most distressing and places patients at risk for dropping out of treatment (Resick, Monson, & Rizvi, 2008).

These exposure techniques are often used in other treatments that also incorporate other components such as cognitive strategies. Particularly for children, the exposure typically occurs in developmentally appropriate ways. See below discussion of TF-CBT and ITCT/ITCT-A.

15.6.3. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, as discussed in the mood disorders chapter, has been proven to be an effective form of treatment for trauma/stress-related disorders. It is believed that this type of treatment is effective in reducing trauma-related symptoms due to its ability to identify and challenge the negative cognitions surrounding the traumatic event, and replace them with positive, more adaptive cognitions (Foa et al., 2005).

Trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy (TF-CBT) is an adaptation of CBT that utilizes both CBT techniques and trauma-sensitive principles to address the trauma-related symptoms. According to the Child Welfare Information Gateway (CWIG; 2012), TF-CBT can be summarized via the acronym PRACTICE:

- P: Psycho-education about the traumatic event. This includes discussion about the event itself, as well as typical emotional and/or behavioral responses to the event.

- R: Relaxation Training. Teaching the patient how to engage in various types of relaxation techniques such as deep breathing and progressive muscle relaxation.

- A: Affect. Discussing ways for the patient to effectively express their emotions/fears related to the traumatic event.

- C: Correcting negative or maladaptive thoughts.

- T: Trauma Narrative. This involves having the patient relive the traumatic event (verbally or written), including as many specific details as possible.

- I: In vivo exposure (see above).

- C: Co-joint family session. This provides the patient with strong social support and a sense of security. It also allows family members to learn about the treatment so that they are able to assist the patient if necessary.

- E: Enhancing Security. Patients are encouraged to practice the coping strategies they learn in TF-CBT to prepare for when they experience these triggers out in the real world, as well as any future challenges that may come their way.

TF-CBT is also beneficial for children that have experienced traumatic grief. The same principles are implemented; however, the intervention provides specifics about implementing the treatment in the context of traumatic grief as well.

Alternatives for Families – A Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (AF-CBT) is another adaptation of CBT for children that have experienced trauma. It is composed of three different general components: child-directed components, caregiver-directed components, and parent-child/family-system directed components. Child-directed components has a similar focus as TF-CBT (e.g., psychoeducation, emotional and cognitive skills, exposure). The caregiver-directed components include a focus on the caregiver’s own psychoeducation, cognitive processing and skills, rapport building with the caregiver, as well as parenting strategies to improve child behaviors. Finally, the parent-child/family-system directed component focuses on communication, problem-solving, and safety/relapse planning. Because there is a strong focus on family, this is sometimes a preferred treatment when it has been observed that caregivers engage in coercive parenting, especially in the context of child physical abuse.

Cognitive Behavioral Intervention for Trauma in Schools (CBITS) is a school-based cognitive behavioral intervention. Although this intervention has some limitations, it is particularly helpful for children and families that do not have easy access to transportation to attend regular mental health therapy appointments in an outpatient setting.

15.6.4. Other Psychological Interventions

Integrative Treatment of Complex Trauma for Children (ITCT-C) and Integrative Treatment of Complex Trauma for Adolescents (ITCT-A) are modular treatments that incorporate several components of various treatment modalities. These treatments allow for more flexibility and tailored intervention plans which can be helpful when children/adolescents present with complex trauma. Because individuals with complex trauma may not have the typical “acute PTSD” symptom presentation, or they may have that presentation with other related symptoms, the flexibility of this treatment allows for many benefits. The provider uses an assessment to identify major problem areas and uses this to target their first goals in therapy. Problem areas may include concerns of safety, issues related to sexual/physical victimization, caretaker support issues, anxiety, depression, aggression, self-esteem, posttraumatic stress, attachment insecurity, identity issues, relationship problems, suicidality, substance use/abuse, grief, sexual behaviors, self- injury, binging/purging, other risky behaviors, legal issues, emotion regulation, flashbacks, and others. The areas of greatest concern are identified as the primary goals that need to be addressed and these goals then align with specific treatment modules.

Throughout therapy, new “problem area” assessments are completed. If the goals are the same, the treatment stays the same. If they are not, then the goals are realigned and new modules, if needed, are implemented. The modules include: cognitive skills, exposure, mindfulness, affect regulation training, trigger management, psychoeducation, relational building/support, safety planning, relational processing, identity issues, interventions, caregiver interventions, and substance abuse interventions. Although the specifics of these interventions vary from ITCT-C and ITCT-A, the concept is similar in both. However, the specific problem areas and modules vary slightly.

15.6.5. Parent-Child Interventions

Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT) was not originally designed for children that have experienced trauma but has proven useful since. The therapy focuses on increasing the positive interaction between a parent and child. The parent learns how to interact with and impose appropriate consequences on a child by watching the therapist interact with the child. Then, they practice what they have learned from the clinician. The therapy typically involves a one-way mirror and an “earpiece” often referred to as “bug in the ear.” This allows the parent to first observe the therapist, but more importantly, it allows the therapist to observe the parent and then coach them through the earpiece on how to interact with the child. This gives the parent real-time coaching.

Child-Parent Psychotherapy (CPP) is used for younger children, as young as infants. The principal behind this treatment is to increase attachment between the child and caregiver. Caregiver needs are addressed in this therapy. For example, often, the caregiver themselves have experienced a trauma. Thus, assessing and addressing PTSD in the caregiver may occur. Also understanding the caregiver’s thoughts and feelings about the child is an important component. With the child, understanding and addressing symptoms of trauma and other emotional or behavioral concerns are addressed. Within the therapy, the child-parent relationship remains the focus. Safety of the child and caregiver home environment is ensured, and limit-setting is established. Parents learn what to expect from their child (e.g., how children express emotion and regulate emotion), and increase the parent’s ability to respond to those emotions. Children and parents learn how to express and receive love and support from each other as well.

15.6.6. Psychopharmacological Treatment

While psychopharmacological interventions have been shown to provide some relief, particularly to veterans with PTSD, most clinicians agree that resolution of symptoms cannot be accomplished without implementing exposure and/or cognitive techniques that target the physiological and maladjusted thoughts maintaining the trauma symptoms. With that said, clinicians agree that psychopharmacology interventions are an effective second line of treatment, particularly when psychotherapy alone does not produce relief from symptoms.

Among the most common types of medications used to treat PTSD symptoms are selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs; Bernardy & Friedman, 2015). As previously discussed in the depression chapter, SSRIs work by increasing the amount of serotonin available to neurotransmitters. Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) are also recommended as second-line treatments. Their effectiveness is most often observed in individuals who report co-occurring major depressive disorder symptoms, as well as those who do not respond to SSRIs (Forbes et al., 2010). Unfortunately, due to the effective CBT and EMDR treatment options, research on psychopharmacological interventions has been limited. Future studies exploring other medication options are needed to determine if there are alternative medication options for stress/trauma disorder patients.

Of course, with any of these medications, the age of the child and severity of the symptoms will be considered before determining if medicinal intervention is appropriate, safe, and necessary.

Key Takeaways

You should have learned the following in this section:

- Several treatment approaches are available to clinicians to alleviate the symptoms of trauma- and stressor-related disorders.

- The first approach, psychological debriefing, has individuals who have recently experienced a traumatic event discuss or process their thoughts related to the event and within 72 hours.

- Another approach is to expose the individual to a fear hierarchy and then have them use positive coping strategies such as relaxation techniques to reduce their anxiety or to toss the fear hierarchy out and have the person experience the most distressing memories or images at the beginning of treatment.

- The third approach is Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and attempts to identify and challenge the negative cognitions surrounding the traumatic event and replace them with positive, more adaptive cognitions. AF-CBT and CBITS are used with children.

- Integrative Treatment of Complex Trauma for Children (ITCT-C) and Integrative Treatment of Complex Trauma for Adolescents (ITCT-A) are modular treatments that incorporate several components of various treatment modalities.

- Parent-child interventions include Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT) and Child-Parent Psychotherapy (CPP).

- Finally, when psychotherapy does not produce relief from symptoms, psychopharmacology interventions are an effective second line of treatment and may include SSRIs, TCAs, and MAOIs.

Section 15.6 Review Questions

- Identify the different treatment options for trauma and stress-related disorders. Which treatment options are most effective? Which are least effective?

- Which treatment approaches are used with children? Describe each.

Apply Your Knowledge

CASE VIGNETTE

Nina is a 14-year-old girl. When Nina was 18 months old, a neighbor called CPS due to concerns that Nina was often dirty, and the neighbor had witnessed aggressive speech and posturing toward Nina from her parents. However, there was not sufficient or concrete evidence of abuse, thus Nina remained in her parent’s custody. During this CPS investigation, Nina’s mother stated to CPS that she was incredibly stressed and also experienced intimate partner violence. She admitted that caring for Nina was difficult because Nina’s was a cranky baby that did not respond to her attempts to soothe. CPS also learned that both parents had a history of substance abuse concerns; however, both parents reportedly were sober and drug/substance free. CPS developed a plan for the family which included parenting classes and a social worker that followed their case for 6 months. After 6-months, Nina’s family appeared to be more stable, and thus, CPS contact ended. However, shortly after, Nina’s parents began using drugs again, and their relationship was more volatile than ever.

When Nina was 13, she had developed a close relationship with the school counselor. One day, the counselor noticed a bruise on her upper arm. Nina trusted her counselor, and after the counselor asked what happened, Nina explained her father had hurt her and showed the counselor other significant bruises. She also told her counselor that her parents often confined her to her room and blamed her for family problems. Nina being the oldest of three also often tried to protect her younger siblings from being hurt. The counselor called CPS and this time, Nina and her siblings were removed from her parents’ custody. Ultimately, Nina’s parents’ parental rights were terminated, and she was adopted by a family after living with 3 foster families. Her siblings were also adopted, but to different families.

After being placed in a foster home, and eventually adopted, Nina became withdrawn and quiet – she spent significant periods alone in her room. Although she was often polite and respectful toward adults, she struggled to engage with peers. She wasn’t interested in extracurricular activities or making friends. Her grades were often Fs, and she was frequently distracted at school. She complained of physical complaints often, with no founded medical conditions. Often, when her adoptive parents raised their voice slightly, she would tear up and run. If her parents dropped something, she would jump. It often seemed to her adoptive parents that Nina had significant difficulty relaxing and always appeared tense. And nearly every night, Nina woke up in a sweat and got little sleep. Her moods shifted from apathetic to hostile and angry quickly. She often displayed emotional outbursts that included verbal and physical aggression. She was recently diagnosed with oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) and ADHD. Nina didn’t talk much about how she was feeling, and her adoptive parents were struggling to figure out how to help Nina.

QUESTIONS TO TEST YOUR KNOWLEDGE

- Do you think Nina is experiencing a trauma-related disorder? If so which one?

- Do you think Nina has ADHD and ODD, or are her experiences better captured by a trauma reaction? Explain your thoughts.

- What treatment options may be best for Nina?

- How can her new family support Nina?

- What protective factors are present for Nina? What risk factors are present?

**Nina’s vignette was heavily informed by Joshua’s vignette published by NCTSN (NCTSN, 2008).**

The National Child Traumatic Stress Network. (2008, March). Child welfare trauma training toolkit: Supplemental handouts. http://www.trauma-informed-california.org/wp- content/uploads/2012/02/child_welfare_trauma_training_ toolkit_supplements.pdf

Module Recap

In Module 15, we discussed trauma- and stressor-related disorders to include PTSD, acute stress disorder, and adjustment disorder. We clarified what stressors and traumas were, forms of childhood maltreatment their impact on children. We also learned about CACs. Next, we discussed how trauma-related disorders present and what the diagnostic criteria are for each. In addition, we clarified the prevalence, comorbidity, and etiology of each disorder. Finally, we discussed the assessment process and potential treatment options for the trauma- and stressor-related disorders, with specific strategies identified for children.

Our discussion in Module 16 moves to eating disorders.

3rs edition