Module 11 – Disruptive, Impulse-Control, and Conduct Disorders

3rd edition as of August 2022

Module Overview

In Module 11, we will discuss matters related to disruptive, impulse-control, and conduct disorders to include their clinical presentation, prevalence, comorbidity, etiology, assessment, and treatment options. We will cover oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, and intermittent explosive disorder. Be sure you refer to Modules 1-3 for explanations of key terms (Module 1), an overview of the various models to explain psychopathology (Module 2), and descriptions of the various therapies (Module 3).

Module Outline

- 11.1. Clinical Presentation

- 11.2. Prevalence and Comorbidity

- 11.3. Etiology

- 11.4. Assessment

- 11.5. Treatment

Module Learning Outcomes

- Describe how disruptive, impulse-control, and conduct disorders present.

- Describe the prevalence of disruptive, impulse-control, and conduct disorders.

- Describe the etiology of disruptive, impulse-control, and conduct disorders.

- Describe how disruptive, impulse-control, and conduct disorders are assessed, diagnosed, and treated.

11.1. Clinical Presentation

Section Learning Objectives

- Describe the presentation and associated features of oppositional defiant disorder.

- Describe the presentation and associated features of conduct disorder.

- Describe the presentation and associated features of intermittent explosive disorder.

11.1.1. Oppositional Defiant Disorder

Oppositional defiant disorder is characterized by a child that is defiant/argumentative, angry/irritable, and vindictive, and has shown this pattern of behavior for at least six months. Of the eight possible symptoms, the child must present with at least four of them. In terms of angry/irritable mood, they may lose their temper often, are easily annoyed or touchy, and are often angry and resentful. In terms of argumentative/defiant behavior the child argues with authority figures, actively defies or refuses to comply, deliberately annoys others, or blames others for their mistakes. Finally, they must have acted spiteful or vindictive at least twice within the past six months. Distress occurs in the child’s immediate social context or affects social, occupational, educational, or other important areas of functioning. Functional consequences of these behaviors include frequent conflicts with parents, teachers, supervisors, peers, and romantic partners (APA, 2022). The disorder typically appears during the preschool years and rarely later than early adolescence.

11.1.2. Conduct Disorder

Conduct disorder is a more severe behavioral disorder in which an individual displays a disregard, not only for rules and authority, but also the rights and conditions of humans and/or animals. Behaviors that may be exhibited are stealing, fighting, cruelty to people or animals, fire-setting, running away from home, bullying or threatening others, using a weapon that can cause harm, committing a mugging or armed robbery, forcing someone into sexual activity, deliberately destroying another person’s property, lying to obtain goods or favors, stealing items of nontrivial value without confronting the victim, staying out at night in clear violation of parental rules, and being truant from school. The preceding represents 15 symptoms of which the person must present with at least three in the past 12 months, with at least one criterion present in the past 6 months.

There are three subtypes of conduct disorder focused on the age of onset. The childhood-onset type occurs prior to age 10 while the adolescence-onset type occurs after age 10. The unspecified onset subtype is used when age of onset is unknown. Males usually receive the childhood-onset subtype and have disturbed peer relationships, likely were diagnosed with oppositional defiant disorder in early childhood, and typically have symptoms that meet full criteria for conduct disorder before puberty.

Conduct disorder is often associated with limited prosocial emotions. To qualify for this specifier, at least two of the following characteristics must have been displayed persistently over the past 12 months and in multiple relationships and settings. These include: a lack of remorse or guilt, a lack of concern for the feelings of others (callous – lack of empathy), being unconcerned about performance, and having shallow or deficient affect.

Functional consequences of these behaviors include being suspended or expulsed from school, problems in work adjustment, legal problems, sexually transmitted diseases, physical injury from accidents or fights, and unplanned pregnancy. It is also associated with early onset of sexual behavior; alcohol, tobacco, and illegal substances use; and reckless and risk-taking behaviors.

The onset of conduct disorder occurs as early as the preschool years, but it is during middle childhood through middle adolescence that the first significant symptoms usually emerge. The DSM states, “Physically aggressive symptoms are more common than nonaggressive symptoms during childhood, but nonaggressive symptoms become more common than aggressive symptoms during adolescence” (APA, 2022, pg. 534).

11.1.3. Intermittent Explosive Disorder

Intermittent explosive disorder is characterized by recurrent behavioral outbursts which represent a failure to control aggressive impulses. It is manifested by one of the following: 1) verbal or physical aggression toward property, animals, or other individuals which occur twice a week on average, for up to three months; and 2) “…three behavioral outbursts involving damage or destruction of property and/or physical assault involving physical injury against animals or other individuals occurring within a 12-month period” (APA, 2022). The level of aggressiveness displayed by the individual is out of proportion with the experienced provocation or stressors and is not for the purpose of achieving a tangible objective such as money, power, or intimidation. The disorder should not be diagnosed in individuals younger than 6 years.

Functional consequences of these behaviors include loss of friends, relatives, or marital instability in the social domain, demotion or loss of employment in the occupational domain, or civil suits due to the aggressive behavior against person or property in the legal domain. There could also be criminal charges and financial loss due to the destruction of objects.

Key Takeaways

You should have learned the following in this section:

- Oppositional defiant disorder is characterized by a child that is defiant/argumentative, angry/irritable, and vindictive and has shown this pattern of behavior for at least six months. At least 4 of 8 symptoms must be present.

- Conduct disorder is a more severe behavioral disorder in which an individual displays a disregard not only for rules and authority, but also the rights and conditions of humans and/or animals. The individual must display at least 3 of the 15 symptoms.

- Conduct disorder is often associated with limited prosocial emotions.

- Intermittent explosive disorder is characterized by recurrent behavioral outbursts which represent a failure to control aggressive impulses.

Section 11.1 Review Questions

- Which of the three disorders discussed in this section is the most severe?

- Which of the three disorders is associated with limited prosocial emotions?

- Which of the disorders is not diagnosed in children under 6 years of age?

- Which disorder is characterized by being irritable, argumentative, and vindictive?

11.2. Prevalence and Comorbidity

Section Learning Objectives

- Describe the prevalence and course of oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, and intermittent explosive disorder.

- Describe comorbid disorders with oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, and intermittent explosive disorder.

- Describe disorders with similar presentations that must be differentiated from oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, and intermittent explosive disorder.

11.2.1. Oppositional Defiant Disorder

11.2.1.1. Prevalence. According to the DSM-5-TR, the cross-national prevalence of oppositional defiant disorder ranges from 1% to 11% with an average prevalence estimate of around 3.3%. The disorder is more common in boys than girls prior to adolescence (APA, 2022).

11.2.1.2. Comorbidity. Oppositional defiant disorder occurs more often in children, adolescents, and adults also diagnosed with ADHD and often precedes conduct disorder. Other comorbid disorders are anxiety disorders and major depressive disorder. Rates of substance use disorders are higher in adolescents and adults diagnosed with oppositional defiant disorder.

11.2.1.3. Differential diagnosis. Oppositional defiant disorder should be distinguished from conduct disorder. Both disorders bring the individual in conflict with adults and authority figures, but the behaviors of oppositional defiant disorder are usually less severe than conduct disorder and do not include aggression toward people or animals, destruction of property, or a pattern of theft or deceit. However, the impairment associated with oppositional defiant disorder may be equivalent or greater than that of conduct disorder. Finally, oppositional defiant disorder includes problems of emotional dysregulation which are absent from conduct disorder.

Oppositional defiant disorder shares with intermittent explosive disorder high rates of anger. However, those with intermittent explosive disorder often show serious aggression toward others that is not characteristic of oppositional defiant disorder.

Finally, stressors may lead to emotional dysregulation, which can present as tantrums and oppositional behavior in children, or aggressive behaviors in adolescents. The DSM says, “Temporal association with a stressor and symptom duration of less than 6 months after the resolution of the stressor may help distinguish adjustment disorder from oppositional defiant disorder” (APA, 2022).

11.2.2. Conduct Disorder

11.2.2.1. Prevalence. In the United States and other largely high-income countries, one-year population prevalence estimates range from 2% to more than 10%, with a median of 4%. In the United States, the lifetime prevalence was 12% among men and 7.1% among women. For those with conduct disorder, suicidal thoughts, suicidal attempts, and suicide occur at a higher-than-expected rate.

In relation to sex and gender-related diagnostic issues, girls and women diagnosed with conduct disorder are more likely to display lying, truancy, running away, and prostitution while boys and men with the disorder exhibit fighting, stealing, vandalism, and school discipline problems. Both boys and men and girls and women display relational aggression, however, girls and women show less physical aggression than boys and men (APA, 2022).

11.2.2.2. Comorbidity. Conduct disorder has been found to be comorbid with ADHD and oppositional defiant disorder, and this comorbid presentation predicts the poorest outcomes. Other comorbid disorders include specific learning disorder, anxiety disorders, depressive or bipolar disorders, and substance-related disorders.

11.2.2.3. Differential diagnosis. Conduct disorder and intermittent explosive disorder share the feature of high rates of aggression, but the aggression in intermittent explosive disorder is limited to impulsive aggression that is not premeditated and does not seek to accomplish an aim such as money, power, or intimidation. Additionally, nonaggressive symptoms of conduct disorder are not present in intermittent explosive disorder.

11.2.3. Intermittent Explosive Disorder

11.2.3.1. Prevalence. The 1-year prevalence in the United States is about 2.6% with a lifetime prevalence of 4.0%. When intermittent explosive disorder is comorbid with PTSD, the rate of lifetime suicide attempts increases (41%; APA, 2022).

11.2.3.2. Comorbidity. Disorders comorbid with intermittent explosive disorder include depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, PTSD, bulimia, binge-eating disorder, and substance use disorders. Additionally, antisocial personality disorder, borderline personality disorder, ADHD, conduct disorder, and oppositional defiant disorder are comorbid.

11.2.3.3. Differential diagnosis. Both intermittent explosive disorder and ADHD share high levels of impulsive behavior, but serious aggression toward others is common with intermittent explosive disorder and not ADHD. As well, those with intermittent explosive disorder do not experience issues with sustaining attention, characteristic of ADHD.

Antisocial and borderline personality disorders share the feature of recurrent, problematic impulsive aggressive outbursts but the level of impulsive aggression is higher with intermittent explosive disorder.

Key Takeaways

You should have learned the following in this section:

- The prevalence of oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder go up to about 10% while intermittent explosive disorder is below 3%.

- When diagnosing any of these disruptive, impulse-control, and conduct disorders it is imperative that they be distinguished from each other to avoid misdiagnosis.

- Oppositional defiant disorder is usually less severe than conduct disorder and though high rates of anger occur with oppositional defiant disorder and intermittent explosive disorder, the serious aggressive behavior toward others is not part of oppositional defiant disorder.

- The three disorders are all comorbid with ADHD, anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, and substance use disorders.

Section 11.2 Review Questions

- Describe the prevalence of the disruptive, impulse-control, and conduct disorders. Which disorder is most common and which is least common?

- Describe patterns of comorbidity across the three disorders and which disorders they are uniquely comorbid with.

- Distinguish the three disruptive, impulse-control, and conduct disorders from one another. What other disorders share features with each?

- Are there any gender differences worth noting with the three disorders?

11.3. Etiology

Section Learning Objectives

- Describe the environmental causes of disruptive, impulse-control, and conduct disorders.

- Describe genetic and physiological causes of disruptive, impulse-control, and conduct disorders.

- Explain the General Coercive Cycle.

11.3.1. Oppositional Defiant Disorder

11.3.1.1. Environmental. Harsh, inconsistent, or neglectful child-rearing practices predict increases in symptoms, and oppositional symptoms predict increases in these types of parenting. Furthermore, when childcare is disrupted by a succession of caregivers, oppositional defiant disorder becomes more prevalent. Finally, children with the disorder are at greater risk of bullying peers as well as being bullied by peers (APA, 2022).

11.3.1.2. Genetic and physiological. Neurobiological markers such as a slower resting heart rate, skin conductance reactivity, reduced basal cortisol reactivity, and abnormalities in the amygdala and prefrontal cortex are associated with oppositional defiant disorder.

11.3.2. Conduct Disorder

11.3.2.1. Environmental. “Parental rejection and neglect, inconsistent child-rearing practices, harsh discipline, physical or sexual abuse, lack of supervision, early institutional living, frequent changes of caregivers, large family size, parental criminality, and certain kinds of familial psychopathology” are all risk factors for conduct disorder at the family level (APA, 2022, pgs. 534-5). Peer rejection, being part of a delinquent peer group, exposure to violence, and neighborhood disadvantage are cited as community-level risk factors.

11.3.2.2. Genetic and physiological. Having a caregiver or close relative that has been diagnosed with conduct disorder leads to a higher risk of a child developing the disorder. Children of parents with severe alcohol use disorder, depressive and bipolar disorders, schizophrenia, ADHD, or conduct disorder are also at higher risk (APA, 2022). Family history may be particularly predictive of a child developing childhood onset, which is considered to have the worst prognosis. Slower resting heart rate, reduced autonomic fear conditioning, and low skin conductance is also noted in individuals with conduct disorder.

11.3.3. Intermittent Explosive Disorder

11.3.3.1. Environmental. Those with a history of physical and emotional trauma during the first 20 years of life are at greater risk of developing the disorder. Within some refugee population settings, long-term displacement from home and separation from family are risk factors (APA, 2022).

11.3.3.2. Genetic and physiological. Genetic factors are a major risk factor, with first-degree relatives of those with intermittent explosive disorder being at increased risk.

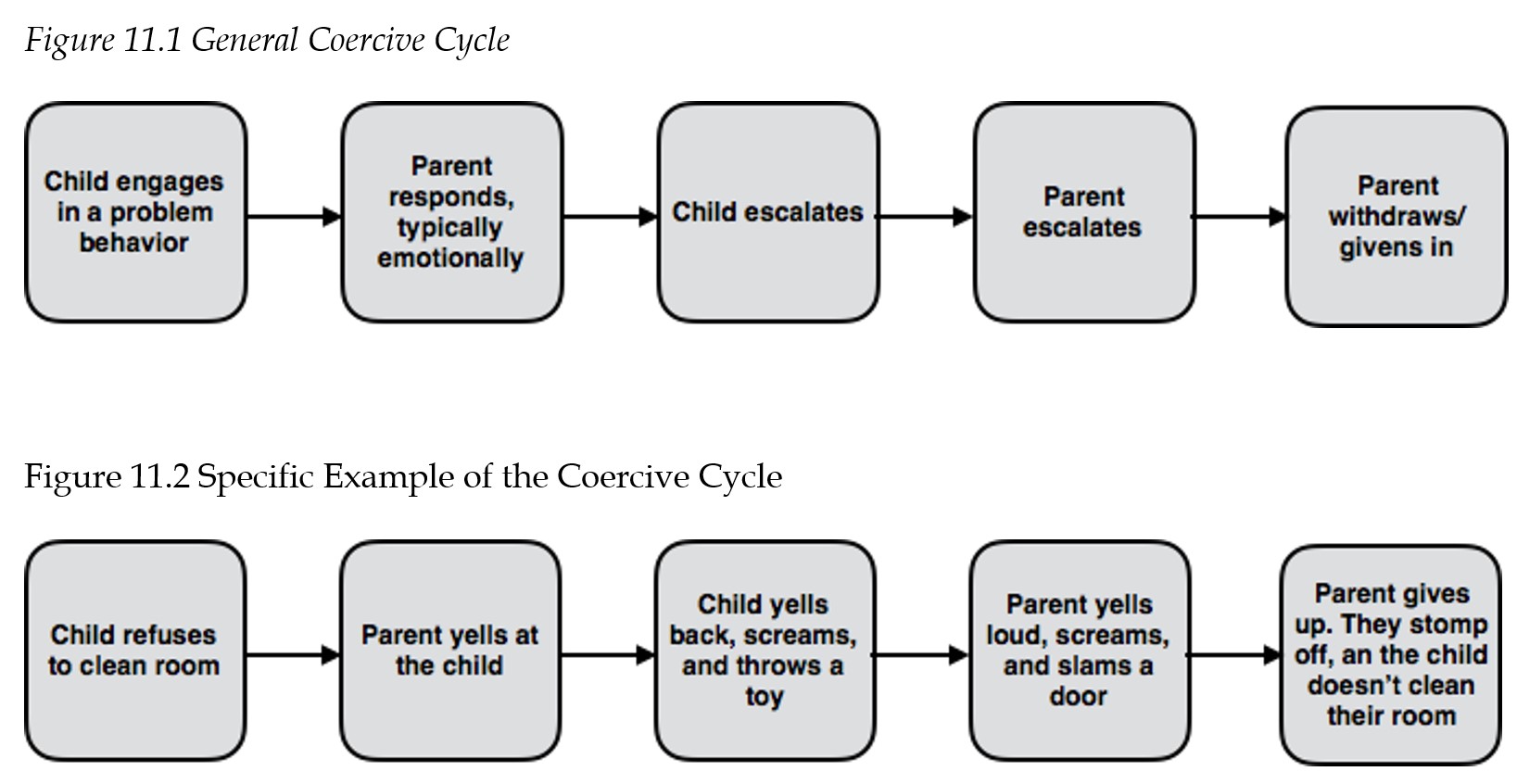

11.3.4. The General Coercive Cycle

Although there are various developmental pathway theories on how these disorders develop, such as Multiple Pathways (Loeber & Stouthamer-Loeber, 1998), Gerald Patterson’s Coercive Family Process Model (1982) is one of the most referenced and utilized theories. The model describes a pattern of interactions that occur within a family. When families engage in negative interactions, children learn and model aggressive behaviors. This is largely grounded in social-learning theory. Ultimately, children learn through negative reinforcement (see Module 3 for a discussion) of coercive parent-child interactions. Most of the parent training protocols to treat behavioral problems are based on Patterson’s model.

Patterson (1982) theorized that various family factors impact a parent’s traits. Those parental traits then disrupt family dynamics which eventually leads to child antisocial behavior. The interactions occurring within these families tend to present as depicted in the figures below. Figure 11.1 gives a general overview of the process and Figure 11.2 gives a more specific example/application of the process.

Key Takeaways

You should have learned the following in this section:

- The disruptive, impulse-control, and conduct disorders are thought to be caused by a series of environmental risk factors such as harsh, inconsistent, or neglectful child-rearing practices.

- Genetic and physiological risk factors are also present for all three disorders.

- The General Coercive Cycle helps to explain socio-cultural causes of these disorders.

Section 11.3 Review Questions

- What are environmental causes of each of the disruptive, impulse-control, and conduct disorders?

- What are genetic/physiological causes of each of the disruptive, impulse-control, and conduct disorders?

- What is the General Coercive Cycle?

11.4. Assessment

Section Learning Objectives

- Describe assessment tools commonly used to diagnosis disruptive, impulse-control, and conduct disorders.

11.4.1. Assessment Tools

When assessing for disruptive, impulse-control, and conduct disorders, the process is very similar to that outlined in the previous chapter on ADHD. Psychologists, again, rely on parent-report, teacher-report, and observations. If the child is old enough, a psychologist will also incorporate the child’s own self-report of symptoms. However, this must be done carefully, because the behaviors being assessed are ones that an individual may be more inclined to under-report or deny. For example, even though an individual may challenge authority frequently, the child may be inclined to answer in a more socially desirable way, denying that they challenge authority. As such, a psychologist must be careful to assess the validity of reports, particularly from self-reports of the child/adolescent.

11.4.2. Observations

Observations can be completed in various ways, similar to observations described for ADHD. However, formal observation may be less necessary. Although formal and inconspicuous observation of a child in the classroom can be valuable, the behaviors in disruptive, impulse-control, and conduct disorders are highly pronounced and noticeable. As such, we tend to rely on parent and teacher reports more heavily. Nonetheless, a psychologist may obtain a good sample of observations when intervening and talking with the child. For example, when interviewing a child, if the psychologist requests the child sit in a particular area, but the child refuses, this may be evidence of defiance. This does not require the psychologist to observe the child in the waiting room or school to gain this information. However, some symptoms, although severe, may occur infrequently. For example, fire setting, although severe, is not likely to occur during an observation period. Though observations are sometimes useful when obtained, this is why they are less critical for diagnosing disruptive, impulse-control, and conduct disorders than they are for a disorder such as ADHD.

11.4.3. Interview

An assessment for disruptive behaviors of disruptive, impulse-control, and conduct disorders should always include some version of an interview which will likely start with a parent. The interview will focus on gaining an understanding of current symptoms and behaviors. Additionally, the time in which symptoms first began will be a critical area of focus, especially when there is concern of conduct disorder. The age at which symptoms were initially noticed is important, due to the impact this has on the child’s prognosis and trajectory. Another important step in the interview process is to assess and understand family and parenting practices, because these factors closely relate to etiology of these disorders as well as treatment implications.

Child interviews will usually be attempted. Sometimes with particularly defiant children, interviews are difficult. However, an attempt should be made. During the interview, a psychologist will note displayed affect and attempt to document the presence of irritability, empathy, prosocial emotions, etc. This information is gained, not only through answers the individual provides, but their tone, body language, and facial expressions. In a sense, a mini observation may occur within the interview.

11.4.4. Objective Measures

A variety of objective measures can be used. These are typically questionnaires that are completed by the parent, teacher, and the child themselves, when appropriate. Children can begin to report on their own symptoms anywhere between the ages of 6-11, depending on the specific questionnaire being used. The mental health professional will generally utilize similar assessments noted in the ADHD chapter, since ADHD has a high comorbidity with oppositional defiant disorder, intermittent explosive disorder, and conduct disorder. Because of this, scales that were designed to assess ADHD also include subscales that measure disruptive, impulse-control, and conduct disorders symptoms and behaviors. As such, scales used include, but are not limited to, the Conners-3, Disruptive Behavior Rating Scales (DBRS), and the NICHQ (National Institute for Children’s Health Quality) Vanderbilt Assessment Scales. The Conners-3 provides both a T-score as well as a symptom count. The DBRS and the Vanderbilt provide a symptom count number. Other questionnaires that may be used, but are not specific for ADHD, are the Behavior Assessment System for Children, Third Edition (BASC-3) and the Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (ASEBA). These forms provide T-scores for scales related to anger/aggression and conduct problems. However, these do not provide symptom counts. As such, the BASC and Achenbach scales are often used in combination with a tool such as the DBRS, Vanderbilt, and/or Conners-3.

Key Takeaways

You should have learned the following in this section:

- We can assess the disruptive, impulse-control, and conduct disorders in a manner very similar to those used for ADHD given the fact that ADHD is comorbid with all three disorders discussed in this module.

- Psychologists rely on parent-report, teacher-report, and observations.

- There are a variety of objective measures that can be used such as questionnaires.

Section 11.4 Review Questions

- Why are many of the same tools used to assess ADHD used to assess the disruptive, impulse-control, and conduct disorders?

- Why are parent and teacher reports used more than observation by the psychologist?

- What information does a psychologist use during an interview?

- When are children able to report their own symptoms on a questionnaire?

11.5 Treatment

Section Learning Objectives

- Describe treatment options for disruptive, impulse-control, and conduct disorders.

- Examine efficacy of the treatment options.

11.5.1. Oppositional Defiant Disorder

11.5.1.1. Psychotherapy. A common treatment option is parent management training (PMT). The goal of parenting training is to help parents implement consistent parenting strategies to increase structure and predictability. For example, parents learn how to deliver instructions and commands to children in a way in which they are more likely to succeed. For example, this could mean breaking large chores down into more manageable pieces. It also requires parents to specifically outline the goal behavior (e.g., put your shoes in your closet) they want to see. This results in gaining the child’s attention (which includes establishing eye contact and may require moving closer to the child or physically directing their attention), saying their child’s name, stating the expectation clearly, and remaining firm with the directive.

PMT also focuses on giving more attention and praise to positive behaviors while ignoring minor misbehaviors. This is in order to increase desired behaviors (if we attend to a behavior, the behavior will increase because attention is a strong reinforcer) and decrease negative behaviors (when we ignore the behavior, we remove attention which reduces the likelihood of it reoccurring since the reinforcer of attention has been withdrawn). It can be challenging for parents to reward or praise behavior that is ‘expected.’ For example, a parent may say “Why am I praising them for brushing their teeth? They should be doing that.” This is a valid and common reaction. However, because the behavior is currently absent, it is necessary to give positive attention to increase that behavior. Think about it, if you get praised by your boss at work, are you going to work harder to get recognized again? Yup, I bet you are! It is the same principal here. In fact, mental health practitioners often use this very analogy to help parents understand this.

PMT also involves teaching parents to systematically implement consequences that reduce elevated emotion. This typically involves removal of privileges or the introduction of undesired activity as well as a time out, when appropriate. There are various, evidenced-based and empirically supported, treatment protocols that target parent management training. The following are examples of such but are not an exhaustive list: Incredible Years Parenting Program, Triple P, Parent-Child Interaction Therapy, Defiant Child, etc. Overall, the goal of these intervention programs is to reduce the likelihood of the parent-child coercive cycle discussed earlier in this chapter.

11.5.2. Conduct Disorder

11.5.2.1. Psychotherapy. Multisystemic therapy (MST) is an intensive treatment option that has demonstrated efficacious results for the treatment of conduct disorder, especially in cases of more extreme conduct problems. MST is a therapy that takes place in the child/adolescent’s home, school, and overall community, in which the therapist works with the child, their family, and other community members. Therapists can be accessed more readily in MST than in other treatment modalities, meet with the child/family multiple times a week and follow a family for several months. This allows more opportunity for meaningful and intensive interventions at the individual, familial, and neighborhood/community level. A recent metanalysis (Tan & Fajarado, 2017) confirmed that, overall, research indicates that MST can lead to improved functioning for children with severe behavioral and conduct problems. Although MST is a preferred treatment modality for youth with conduct disorder, it is costly and difficult to obtain in some areas of the country, due to lack of resources. However, MST may be less costly than typical services in the short-term due to costs saved from a reduction in crime and incarceration (Tan & Fajarado, 2017). Other studies (e.g., Dopp, Borduin, Wagner, & Sawyer, 2014) have shown similar benefits as those found in Tan and Fajarado’s (2017) study.

11.5.3. Intermittent Explosive Disorder

Psychology Today notes that the treatment of intermittent explosive disorder can be highly effective if started as early as possible. They write, “School-based violence prevention programs, for example, may lead to early identification of intermittent explosive disorder cases, leading to treatment that could prevent associated psychopathology.” Treatment involves a combination of medication and psychotherapy. In terms of the latter, cognitive behavioral therapy can aid individuals in developing coping mechanisms, such as relaxation techniques, to deal with their impulses. Group counseling and anger management programs are also used.

In terms of medication, no specific medications exist for treating the disorder. That said, medications such as anti-depressants, anti-anxiety agents, anticonvulsants, and mood stabilizers can be used by reducing the impulsive behavior or aggression. They conclude, “Since intermittent explosive disorder can be comorbid with conditions such as anxiety or depression, clinicians need to factor that into their treatment plan, especially if medication is used.”

To see the article for yourself, please visit:

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/conditions/intermittent-explosive-disorder#treatment

11.5.4. Psychopharmacology

Medications are not used to address symptoms of behavioral disorders. However, if a child has a behavioral disorder and comorbid impulsivity or mood concerns (see relevant modules for more information), medications may be used to address those concerns as they may exacerbate disruptive, impulse-control, and conduct disorders symptoms.

Key Takeaways

You should have learned the following in this section:

- Psychotherapy can be used to treat the disruptive, impulse-control, and conduct disorders discussed in this chapter.

- Generally speaking, medications are not used to address symptoms of behavioral disorders.

Section 11.5 Review Questions

- What is parent management training and what disorder is it used for?

- What is multisystemic therapy and what disorder is it used for?

- How is CBT used to treat intermittent explosive disorder?

- Are medications effective for treating disruptive, impulse-control, and conduct disorders? If so, how?

Apply Your Knowledge

CASE VIGNETTE

William is a 16-year-old boy that lives with his mother. He has never met his father, but his father and his paternal family have a long history of incarceration. William’s mother has worked hard to provide a safe home for William and meet all of his needs. However, to do that, she has to work two jobs, and that means William is often at home alone or unattended. He has been involved in school sports; however, his grades dropped which got him kicked off the school sports teams. He has a group of friends that he gets along with and considers to be a strong support system. He and his friends often skip class and William has smoked marijuana with his friends at times, although he reports that he does not do this regularly. William has never stolen anything, he’s never had contact with the legal system, and he has a part-time job that he has kept for 8 months now. William and his baseball coach have a strong connection, and his coach has been working with William to get his grades up so that he can rejoin the baseball team.

QUESTIONS TO TEST YOUR KNOWLEDGE

- What risk factors are present for William?

- What protective factors are present for William?

- Does he meet criteria for one of the disorders discussed in this module? Why or why not?

Module Recap

In this module, we learned about disruptive, impulse-control, and conduct disorders. We discussed the various behaviors and symptoms of oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, and intermittent explosive disorder and how they relate to the various presentations. We then discussed the prevalence of these disorders, frequently comorbid disorders, and the etiology of the disruptive, impulse-control, and conduct disorders. In our discussion of etiology, we also learned about the coercive cycle. We ended on a discussion of how the disruptive, impulse-control, and conduct disorders are assessed and treated. Note that the DSM also includes descriptions of pyromania and kleptomania, both of which are thought to start in adolescence.

This concludes our discussion of behavior-related disorders. In the next unit we will discuss mood-related disorders which includes depressive and bipolar-related disorders.

2nd edition